Among the 900 or so texts of the Dead Sea Scrolls is the Book of Jubilees, a second- century retelling of Genesis and the first part of Exodus.

Originally written in Hebrew, Jubilees continues to interest scholars for its commentary on the earlier texts.

James VanderKam is the John A. O’Brien Professor of Hebrew Scriptures at the University of Notre Dame and a scholar of the Dead Sea Scrolls, a collection of ancient religious texts found between 1947 and 1956 in caves in and around Qumran, along the northwest shore of the Dead Sea about 15 miles east of Jerusalem.

VanderKam is one of the scholars working on the original Hebrew text of the Book of Jubilees. He has edited the fragmentary remains of several manuscripts—describing them, noting their measurements and details like the writing itself and to what time they can be dated. He has also translated the book from the original texts.

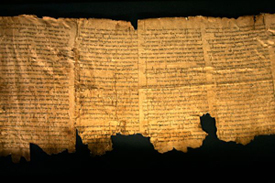

Often written in Hebrew or Aramaic on treated leather parchment, some of the scrolls have holes that can present a problem for editors. VanderKam has worked with the scrolls first- hand, though he mostly works from high quality photographs. He says it is possible to mistake a small mark for part of a letter— which is why checking the original text is so important.

“Despite the fact I have literally worked with every word in the Book of Jubilees by editing the text and writing about it, I keep finding new things,” says VanderKam. By returning to the original manuscripts, he has identified problems in previous translations.

Case in point: Jubilees’ account of the story of Enoch. According to the story, God took Enoch—who lived before the flood and whose life ended without death—to the Garden of Eden to record the deeds of humanity.

A previous English translation of the Ethiopic text states in chapter 4 verse 24: “on account of it God brought the waters of the flood upon all the land of Eden.”

The problem, says VanderKam, is that the translation implies that God brought the flood on Eden because of Enoch’s presence there. “That doesn’t make any sense,” he says, “because Enoch continues to live—he doesn’t drown in the flood.”

VanderKam’s research revealed what the text actually says: “Because of him, God did not bring the waters of the flood on Eden.”

Why the mistranslation? It turns out that the Ethiopic words for “he brought” and “it did not come” look almost exactly the same: The mistranslation was the result of a visual misinterpretation.

VanderKam is particularly interested in how the author of Jubilees worked with Genesis and Exodus, commenting on and solving problems in the original texts. “It’s a very, very early stage in the process of commenting on the Bible, which goes on today,” he says. “It feels good to be part of that tradition.”

Although Jubilees’ author is unknown, VanderKam says that its intention is clear: The author thought Genesis and Exodus were very important books, and wanted people to draw the correct conclusions. “He retold them in such a way as to get across the message he thought they had,” says VanderKam. There’s reason to think that Jubilees was an authoritative text in its own right because it was cited in other ancient texts, VanderKam adds.

Between 70 and 80 scholars have worked on editing the scrolls, says VanderKam. It was an international effort, and one that involved scholars from Jewish, Christian and other traditions. “It’s been a real ecumenical experience in which I think everyone has appreciated the contributions of the others,” says VanderKam. “To get the chance to go back 2,000 years and see what the texts looked like is quite a privilege.”

Contact: James VanderKam, 574-631-3421, jvanderk@nd.edu