Introduction

The Reading Buddies program

was a new program in 2011 at Grande Prairie Public Library. This program is modelled

on the Partners in Reading program that took place at this library from 1990 to

2008. In 2011, the program was adapted to reflect the current needs of the

community.

The new program was

intended to pair teen volunteers with lower elementary students for reading

practice and fun activities over the summer.

In 2011, Grade 1 to 4 students were invited to participate in the

program. In 2012, this was changed to

Grades 1 to 3, as there was greater demand for the program from families of

younger students in 2011. The large age

range also made it difficult to plan developmentally appropriate group

activities. The program was marketed towards struggling readers, but children

at any reading level could participate in the program.

Volunteer recruitment

expanded to include college students and some adults when it became clear that

we would have far more child participants than teenage volunteers. In 2011 there were 19 teen and 9 adult

volunteers. (As some of the teens volunteered for more than one session, 28 of

the 37 pairs had teen volunteers.) In

2012, there were 29 teen and 5 adult volunteers and of the 44 pairs, 39 had

teen volunteers. In 2011, volunteers attended an hour-long training session

before the start of the program, in which they learned ways to facilitate the

reading process. In 2012, we extended

the training session to one and a half hours to accommodate activities and

discussion about strategies for reading with their partners, rather than the

simple presentation we had done the year before.

Each year, the program

ran for seven weeks during the summer.

Each session of Reading Buddies was an hour and a half long. Approximately one hour of this time was spent

in one-on-one reading. The pairs also

had the option of using literacy-based games and activities during this

time. The other half hour was spent in

group activities, including storytimes, puppet shows,

and interactive story-based activities.

Reading Buddies gives

children the opportunity to practice reading throughout the summer, a time when

many children fall behind in reading fluency.

In order to be successful, Reading Buddies should have an impact on the

children who participate. The study was

designed to assess the program’s impact on the children’s reading abilities and

attitudes towards reading.

Literature Review

The Summer Reading Gap

There are few who

doubt the importance of the ability to read. Reading is necessary for success

in a world in which text is a major medium for communication. Children who are fluent readers will be more

successful in school and as adults, but attaining that level of reading ability

requires practice (Ross, 2006). As elementary students, children will

naturally learn at different rates and be subject to outside influences such as

socio-economic status and family literacy.

Research in education

has identified what is known as the “summer reading gap.” This is a phenomenon in which some children

maintain or increase their reading level over the summer holiday, whereas other

students seem to go backwards in development (Roman, Carran, & Fiore,

2010). This effect is cumulative, leading to greater

and greater discrepancies in ability as children progress through school. The summer reading gap has also been linked

to socio-economic status, as students from higher income families tend to have

greater access to libraries and other learning opportunities during the summer

months (McGill-Franzen

& Allington, 2003).

As Heyns (1978) initially pointed

out, public libraries are in a unique position to address the summer reading

gap. Not only are they open during the

summer, but libraries have been offering variations of the summer reading

program for over a century (Roman et al., 2010). Today, almost all libraries

offer free, structured reading programs for children of all ages. This programming serves to motivate children

to continue reading while they are out of school, and thus may serve to prevent

or limit summer learning loss.

Although there is a field of research addressing

the summer reading gap from the education perspective, relatively little

literature directly examines how summer reading programs

in libraries impact student achievement.

Heyns’s (1978) study found that children who

participated in summer reading programs gained more vocabulary than children

who did not, regardless of socioeconomic status, gender, or number of books

read. Roman et al. (2010) recently conducted a

large-scale longitudinal study, comparing students who participated in summer

reading programs at libraries with students who did not. Overall, this study showed that children who

participated in voluntary summer reading programs increased their reading

levels more than children who did not.

In the research that does exist, it seems that voluntary participation in a reading program has more impact than

forced reading, whether at home, summer school, or the library. It appears that the greatest factor in summer

reading achievement may be access to and regular use of library materials and

programs.

Reading Partner Programs

There have been a

number of studies on tutoring programs for reading skills. Many of these programs took place in schools

and run throughout the school year (Block & Dellamura,

2001; Burns, Senesac, & Silberglitt,

2008; Fitzgerald, 2001; Gattis et al., 2001; LaGue & Wilson, 2010; Marious,

2000; Paterson & Elliott, 2006; Theurer &

Schmidt, 2008; Vadasy, Jenkins, Antil,

Wayne, & O’Connor, 1997). Several

programs specifically targeted students at risk of reading failure (Burns et

al., 2008; Fitzgerald, 2001; Gattis et al., 2001; LaGue & Wilson, 2010; Paterson & Elliott, 2006; Vadasy et al., 1997).

All of these programs

showed an improvement in the students’ reading abilities. Burns et al. (2008) studied the long-term

effects of a reading program, and found that two years after the Help One

Student to Succeed (HOSTS) program, HOSTS students had higher fluency,

comprehension, and reading progress scores than non-HOSTS students.

The length of the

program is an important factor.

Fitzgerald’s (2001) study of a tutoring program compared a group of

students who received tutoring for a full term and students who were tutored

for less than the full term. The

students who were tutored for the full term showed higher gains in reading

ability. Fitzgerald also noted that

students showed greater growth in the second half of the program, and that

different skills improved at different points in the program: during the first

half, students showed more improvement in phonological awareness, whereas in

the second half there was greater improvement in reading words.

The tutors also

impacted the effectiveness of the programs.

The age of tutors does not appear to be an important factor: programs

with volunteers who were peers (LaGue & Wilson,

2010), older students (Block & Dellamura, 2001; Marious, 2000; Paterson & Elliot, 2006; Theurer & Schmidt, 2008), college students (Fitzgerald,

2001), adults (Jalongo, 2005), or a mix of community

volunteers (Gattis et al., 2010; Vadasy

et al., 1997), all showed improvements in students’ reading. In all of these studies, tutors received some

form of training. Vadasy

et al. (1997) studied a program with very structured lesson plans and found

that the “children whose tutors implemented the lessons as designed

demonstrated significantly higher reading and spelling achievement” (Lesson

Content section, para. 2). Though not studied in

depth, Theurer and Schmidt (2008) noted that while

some of the “fifth-grade buddies were naturals and interacted comfortably with

the first graders, others seemed uncertain and tentative, not quite knowing

what was expected of them” (p. 261). They integrated training on choosing

books, reading strategies, and interpersonal skills into the program.

Because these studies look at programs that

are based in schools and run throughout the school year, the programs are

longer than our summer Reading Buddies program, which runs for seven

weeks. As shown in Fitzgerald’s (2001)

study, the length of the program can impact the students’ gains in reading.

The structure of the programs studied varied,

and it is difficult to compare the effects of each program. Vadasy et al.’s

(1997) conclusions support a more structured program. Our Reading Buddies program was loosely

structured, with the majority of the time spent reading one on one with the

volunteers, so it is important to have a closer look at the effects of a loosely

structured program on students’ reading abilities.

Reading Abilities and

Attitudes

Reading Buddies aims

to improve children’s reading abilities, but also to instill a positive

attitude about reading. The two factors

are intricately related. It seems that

students who have a negative attitude about reading are less likely to read

voluntarily and will read less overall than their reading-positive companions

(Sainsbury & Schagen, 2004). Over time, this leads to larger and larger

gaps in ability between students.

Research has indicated that reading achievement and attitudes about

reading are related among elementary students (Diamond & Onwuegbuzie, 2001).

Indeed, McKenna and Kear (1990) developed the

Elementary Reading Attitudes Survey (ERAS) as another way (besides reading

tests) for teachers to assess their students.

Logan and Johnston

(2009) studied over 200 students in order to compare reading abilities and

attitudes between boys and girls. They

found that girls had more positive attitudes towards reading overall, and that

this was correlated with their reading ability.

Interestingly, the relationship between reading attitude and ability was

found to be weaker in boys than in girls.

The Dominican Study

(Roman et al., 2010) revealed that most librarians perceived that their programs

had a positive effect on students’ reading levels and attitudes about

reading. Block and Dellamura

(2001) also observed that children placed a higher value on reading at the end

of their tutoring program. However, the

students’ attitudes about reading were never directly tested in either

program.

Aims

The goal of the study

was to test two hypotheses:

- Hypothesis 1: Children enrolled in the

Reading Buddies program will have better reading skills at the end of the program

than at the start of the program.

- Hypothesis 2: Children enrolled in the

Reading Buddies program will have a more positive attitude towards reading

at the end of the program than at the start of the program.

Methods

Reading Test

We used the Graded

Word Recognition Lists from the Bader

Reading and Language Inventory (6th ed., 2008) to test the participants’

reading skills. The Graded Word

Recognition Lists “can serve as a quick check of the student’s word recognition

and word analysis abilities” (Bader & Pearce, 2008, p. 4). They do not measure other reading skills such

as comprehension.

The test consists of

several lists of progressively more difficult words. This test was chosen because it covered a

wide range of reading levels (preschool to high school), had been updated

recently, and could be easily administered within the limited time we had

available. While the test is American,

the words chosen did not reflect any regional spelling variations. Differences in the American and Canadian

school systems may have made the grade level results inaccurate; however, we

were interested only in the change in reading level, not the grade levels

themselves.

The test was

administered one on one during the first and last sessions of the Reading Buddies

program.

Elementary Reading

Attitudes Survey

We used a modified

version of the ERAS, or Elementary Reading Attitudes Survey (McKenna & Kear, 1990),

to evaluate how participants’ attitudes about reading changed over the duration

of the Reading Buddies program. This

survey was originally developed as a way for teachers to determine how their

students felt about reading. It has also

been used for research studies about reading attitudes (Black, 2006; Martinez, Aricak, & Jewell, 2008; Worrel,

Roth, & Gabelko, 2002), mostly in school

settings.

The ERAS uses images of the popular comic book

character, Garfield, to elicit participants’ emotional responses about

reading. Questions ask “How do you feel

…?” about a reading-related activity and participants circle one of four images

of Garfield that corresponds with their feeling.

The ERAS was extensively tested during its

development to determine its validity and reliability. After the format and items had been decided

upon, the researchers administered the test to over 18,000 first- to

sixth-grade students across the United States. Calculation of Cronbach’s Alpha revealed high internal consistency of

items within each sub-scale. To

determine the validity of the survey, participants were asked directly about

their reading habits and other activities.

High scores on the survey, indicating a very positive attitude towards

reading, were correlated with literary activities such as good access to school

and public libraries. Low scores on the

survey were correlated with non-literary activities such as large amounts of

television-watching.

The survey contains two sub-scales, one

measuring recreational reading and one measuring academic reading. For the purposes of this research, we only

used the first sub-scale. We chose to eliminate the second sub-scale because of

frequent references to the school context, which are not suited to our purpose.

In each year of the study, the ERAS survey was

administered to the groups of Reading Buddies participants during the first and

last sessions of the program. The 10

questions of the first sub-scale were read aloud to the participants, who

completed their own paper copy of the survey.

Demographics and

Program Participation

As part of the ERAS,

participants were also asked for their grade and sex. During the program, attendance records were

kept, so there was a record of how many sessions each child attended.

Results

In 2011, 19 out of the

37 children participating in the program completed both the pre- and

post-tests. In 2012, there were 18

Reading Buddies participants who took part in the study (although only 17

completed both the pre- and post-test of the ERAS), for a total of 37 study participants

over two years.

Nineteen of the study

participants were boys and 18 were girls.

The breakdown of grades they had just completed was as follows:

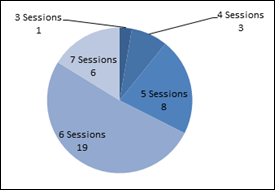

Figure

1

Grades completed by

Reading Buddies participants

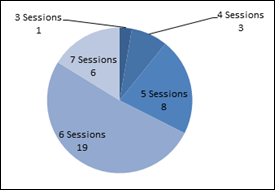

During registration,

we asked that parents register their children in Reading Buddies only if they

expected to be able to attend at least five of the seven sessions. Figure 2 shows the number of participants

grouped by the number of sessions they attended.

Figure

2

Number of sessions

attended by Reading Buddies participants

Reading Test

Participants were

given a score on the reading test between -1 (preschool) and 9 (high

school). The score is intended to

reflect a normal reading level for a student’s grade (e.g., a score of 2 is a

second-grade reading level). Half scores

could also be given (e.g., 1.5). We

subtracted the participants’ pre-test reading scores from their post-test

reading scores to determine the change in reading level.

On average, there was

a small increase in the participants’ reading levels over the course of the

program. The average change in reading

test scores was 0.08. The range for the

change in reading test scores was from -1.5 to 2. Ten participants showed an increase in

reading score, 8 showed a decrease, and 19 showed no change. As Figure 3 shows, few children’s

reading levels changed by more than 0.5 in either direction.

Figure

3

Changes in reading test

scores between the first and last sessions of Reading Buddies

The number of sessions

may have had an impact on the changes in reading levels, with a correlation

coefficient of 0.13. The average change

in reading score increased with the number of sessions attended, up to six

sessions. See Table 1.

Few children attended

fewer than five sessions (over half the study participants came to six

sessions), so results here are also not conclusive.

Table 1

Average Change in

Reading Level by Number of Sessions Attended

|

Number of Sessions

Attended

|

Average Change in

Reading Level

|

|

3

|

-0.5

|

|

4

|

-0.17

|

|

5

|

0.06

|

|

6

|

0.18

|

|

7

|

0

|

Grade level also

appeared to make a difference to changes in reading levels. Between

kindergarten and Grade 2, the change in reading level became more positive as

the grade level increased. However, the correlation

coefficient was not significant at -0.01.

While it appears that the program’s positive effects peak around Grade

2, it is important to keep in mind that the majority of the study participants

were in first and second grade (only two third-grade students participated in

the study).

The program also had a

bigger impact on girls’ reading scores than on boys’, though overall it did

have a small positive impact on both.

The average change in score for girls was 0.14 and for boys was 0.03.

Reading Attitudes

Survey

All participants were

given a reading attitudes score between 10 and 40, with higher scores

indicating a more positive attitude towards reading. Contrary to our expectations, the average

change in ERAS scores between the first and last sessions was a decrease of

1.17 points. The change in ERAS scores

ranged from -14 to 15. Sixteen

participants showed an increase in their ERAS score, 19 showed a decrease, and

1 showed no change. While there was a

wide range in changes to the ERAS scores, large changes in ERAS scores were

uncommon: the majority or participants remained within 5 points of their

pre-test score. See Figure 4.

Figure

4

Changes in ERAS scores between the first and last

session of Reading Buddies

There was no

correlation between the number of sessions attended and changes in ERAS scores.

There appeared to be a

relationship between the grade level of the child and the changes in their

attitude toward reading in the 2011 group — the positive effects of the program

increased up until the third grade — however, this was not so evident once the

2012 data was added. The correlation

coefficient for last completed grade and change in ERAS score was 0.29. As there were only two third-grade students

and three kindergarten students who participated in the study, it is difficult

to draw any conclusions about these results.

The program had

slightly less impact on girls’ ERAS scores than on boys’, although both sexes

show a slight decrease in attitude towards reading over the summer. On average, the female participants’ scores

decreased by 0.35 points and the male participants’ scores decreased by 1.89

points. See Figure 5.

Figure 5

Sex differences between ERAS scores

In general, the boys

also had lower raw scores on the ERAS test than the girls. In the pre-test, girls scored an average of

35.88 versus boys’ average scores of 30.42.

The post-test revealed similar results, with girls scoring 35.53 and

boys scoring 28.53.

Discussion

The small number of

participants in this study makes drawing any strong conclusions difficult. Our results show some interesting trends with

regard to what effect the Reading Buddies program has had on its participants,

but it is difficult to declare whether the program was successful or not. On average, the participants showed a slight

increase in their reading level over the summer and their attitudes about

reading became slightly more negative; however, the changes were very

small. Many participants maintained the

same reading level and a similar attitude towards reading.

Although the average

change in score for the reading test was slightly positive, there were some

participants whose reading levels decreased between the pre- and

post-test. This may be a symptom of the

overall learning loss that occurs during the summer. Since we have no control group for comparison,

it is difficult to evaluate whether our program made a significant difference

in combating summer learning loss.

The research

demonstrates that the more sessions the children attended, they more likely it

was that their reading abilities would increase. This should be emphasized to parents, so that

fewer sessions are missed during the summer.

It is also possible that a longer program would have a more positive

impact (e.g., a program run during the school year). We suspect that the short duration of the

program will prohibit it from ever causing large increases in reading ability;

however, the number of sessions seems to be sufficient to help maintain reading

levels.

For several of the

participants, the program had a negative impact on their attitude towards

reading. Though it is impossible to say

why this was the case, the child’s attitude towards participating in the

program may have been a factor.

Participants may have attended the program at the behest of parents or

teachers, rather than of their own volition.

Selection bias may also have been a factor, as the program was marketed

towards struggling readers, who may have a more negative attitude towards

reading than the general population.

However scant the data

may be, this information may point in the direction of potential changes to the

program. On average, the boys entering

the program had less positive attitudes towards reading than the girls, and

also saw less positive effects from the program on both measures. This is consistent with research indicating

that boys generally fall behind girls in reading level as they progress through

school (Taylor, 2005). Better results for boys might be achieved if

more attention were paid to their particular needs and interests.

There were many

factors that could not be measured in this study. The Reading Buddies sessions were loosely

structured, and the pairs had choices with regards to how much time they would

spend reading, discussing the books, and playing literacy-based games. The impact of supplementary activities versus

time spent in one-on-one reading during the program was not measured. The task

of keeping a record of the time spent on various activities may have distracted

volunteers from their most important task: engaging with their younger

partners. Additionally, some activities (e.g., reading and discussion) are so

intertwined that measurements of time spent on them were unlikely to be

accurate.

The volunteers’ skill

as reading partners was also not taken into account. Volunteers all received

the same training; however, many other factors affected their performance, such

as personality, previous experience in similar programs, comfort levels with

children, willingness to ask for help, and improvement over the course of the

program. Quantifying the volunteers’

skill as reading partners was impractical given the number of factors involved.

There were also

factors outside of the program that we were unable to measure. As discussed, voluntary reading is more

effective than forced reading at reducing the summer reading gap (Roman et al.,

2010). It stands to reason that

participants who were motivated to read on their own may have had more success

in the program than those who did not read voluntarily. Unfortunately, we had no way of accurately

measuring how much voluntary reading participants were doing outside of the

program.

During the program, it

was casually observed that some of the participants’ parents were more

enthusiastic about reading than others.

This behaviour included making an effort to

attend every session, encouraging children to check out books, bringing the

family to other reading programs at the library, and reading books themselves

while waiting for their children. It

would be very interesting to see if this parental influence was related to

improvements in reading level and attitudes, however we had no way of

determining this during the first two years of the program. For future years, we hope to provide parents

with information or training at the start of the program to emphasize the

importance of modelling reading behaviour

within the family.

Conclusions

This study was

undertaken to determine how our library’s summer reading mentor program would influence

the participants’ reading abilities and attitudes about reading.

Our first hypothesis

about the Reading Buddies program was supported: on average, the effects of the

program on reading skills were positive.

However, due to the small number of participants, further study will be

needed to confirm these results. It is

also clear that, while reading levels may improve slightly during Reading

Buddies, maintaining children’s reading levels is a more realistic goal for

this program.

The second hypothesis,

which postulated that the program would lead to an increase in positive

attitudes about reading, was not supported by the data gathered. Some participants did demonstrate a higher

score on the post-test, as compared to the pre-test, but on average the study

showed a small negative impact on attitude towards reading. Due to the small number of participants,

further study will be needed to confirm these results.

It appears that

Reading Buddies helps to combat summer learning loss, both reading abilities

and attitudes; however a study with a control group would provide stronger

evidence for this finding.

References

Bader, L. A., &

Pearce, D. L. (2008). Bader Reading

and Language Inventory. 6th ed. Pearson.

Black, A.-M. L. (2006). Attitudes

to Reading: An Investigation Across the Primary Years. Virginia, QLD:

Australian Catholic University.

Block, C. C., & Dellamura, R. J.

(2000/2001). Better book buddies. The Reading Teacher, 54(4), 364-70.

Burns, M. K., Senesac, B. J., & Silberglitt,

B. (2008). Longitudinal effect

of a volunteer tutoring program on reading skills of students identified as

at-risk for reading failure: A two-year follow-up study. Literacy Research and Instruction, 47(1), 27-37. doi:10.1080/19388070701750171

Diamond, P. J., & Onwuegbuzie, A. J. (2001).

Factors associated with reading achievement and attitudes among

elementary-aged students. Research in the

Schools, 8(1), 1-11.

Fitzgerald, J. (2001). Can minimally trained

college student volunteers help young at-risk children to read better. Reading Research Quarterly, 36(1),

28-46.

doi:10.1598/RRQ.36.1.2

Gattis, M. N.,

Morrow-Howell, N., McCrary, S., Lee, M., Jonson-Reid, M., McCoy, H., Tamar, K.,

Molina, A., & Invernizzi, M. (2010). Examining the effects of

New York Experience Corps® program on young readers. Literacy Research and Instruction, 49(4), 299-314. doi:10.1598/RRQ.36.1.2

Heyns, B. (1978). Summer

Learning and the Effects of Schooling. New York: Academic Press.

Jalongo, M. R. (2005). Tutoring young children’s reading

or, how I spent my summer vacation. Early

Childhood Education Journal, 33(3),

121-123.

LaGue, K. M., & Wilson,

K. (2010). Using peer tutors to

improve reading comprehension. Kappa

Delta Pi Record, 46(4), 182-186.

Logan, S., &

Johnston, R. (2009). Gender differences in reading

abilities and attitudes: Examining where these differences lie. Journal

of Research in Reading, 32(2), 199-214.doi:10.1111/j.1467-9817.2008.01389.x

Marious, S. E., Jr. (2000). Mix and match: The effects of cross-age tutoring

on literacy. Reading

Improvement, 37(3), 126-130.

Martinez, R. S., Aricak, O. T., & Jewell, J. (2008). Influence of reading attitude on reading

achievement: A test of the temporal-interaction model. Psychology in the

Schools, 45(10), 1010-1022. doi:10.1002/pits.20348

McGill-Franzen, A., & Allington, R.

(2003). Bridging

the summer reading gap. Instructor, 112(8),

17-20.

McKenna, M. C., & Kear, D. J. (1990). Measuring attitude toward reading:

A new tool for teachers. The Reading Teacher, 43(8), 626-639.

Paterson, P. O., & Elliott, L. N. (2006). Struggling reader to struggling reader: High

school students’ responses to a cross-age tutoring program. Journal

of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 49(5),

378-389. doi:10.1598/JAAL.49.5.2

Roman, S., Carran, D. T., & Fiore, C. D. (2010). The

Dominican Study: Public Library Summer Reading Programs Close the Reading Gap.

River Forest, IL: Dominican University. Retrieved 22 Feb. 2013 from http://www.dom.edu/gslis/downloads/DOM_IMLS_book_2010_FINAL_web.pdf

Ross, C.S. (2006). The

company of readers. In C.S. Ross, L. McKechnie,

& P.M. Rothbauer, Reading Matters: What the Research Reveals about Reading, Libraries,

and Community. (pp. 1-62). Westport, Connecticut: Libraries Unlimited.

Sainsbury, M., & Schagen, I. (2004). Attitudes to reading at ages nine and eleven. Journal of Research in Reading, 27(4),

373-386. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9817.2004.00240.x

Taylor, D. L. (2005). “Not just boring stories”: Reconsidering the

gender gap for boys. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 48(4), 290-298. doi:10.1598/JAAL.48.4.2

Theurer, J. L., & Schmidt,

K. B. (2008). Coaching reading

buddies for success. The

Reading Teacher, 62(3), 261-64.

doi:10.1598/rt.62.3.8

Vadasy, P. F., Jenkins, J. R., Antil,

L. R., Wayne, S. K., &

O'Connor, R. E. (1997). The effectiveness of one-to-one tutoring by community tutors for

at-risk beginning readers. Learning Disability Quarterly, 20(2),

126-39. doi:10.2307/1511219

![]() 2013 Dolman and Boyte-Hawryluk.

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative

Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 2.5 Canada (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.5/ca/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

2013 Dolman and Boyte-Hawryluk.

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative

Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 2.5 Canada (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.5/ca/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.