Article

A Citation Analysis of the Classical Philology

Literature: Implications for Collection Development

Gregory A. Crawford

Director, Penn State

Harrisburg Library

Middletown, Pennsylvania,

United States of America

Email: gac2@psu.edu

Received: 07 Dec. 2012 Accepted: 15

Feb. 2013

2013 Crawford. This is an Open Access article

distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 2.5 Canada (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.5/ca/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

2013 Crawford. This is an Open Access article

distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 2.5 Canada (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.5/ca/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

Abstract

Objective – This

study examined the literature of classical (Greek and Latin) philology, as

represented by the journal Transactions

of the American Philological Association (TAPA), to determine changes over time for the types of materials cited,

the languages used, the age of items cited, and the specificity of the

citations. The overall goal was to provide data which could then be used by

librarians in collection development decisions.

Methods

– All citations included in the 1986 and

2006 volumes of the Transactions of the

American Philological Association were examined and the type of material,

the language, the age, and the specificity were noted. The results of analyses

of these citations were then compared to the results of a study of two earlier

volumes of TAPA to determine changes

over time.

Results

– The analyses showed that the

proportion of citations to monographs continued to grow over the period of the

study and accounted for almost 70% of total citations in 2006. The use of foreign

language materials changed dramatically over the time of the study, declining

from slightly more than half the total citations to less than a quarter. The

level of specificity of citations also changed with more citations to whole

books and to book chapters, rather than to specific pages, becoming more

prevalent over time. Finally, the age of citations remained remarkably stable

at approximately 25 years old.

Conclusion – For librarians who manage collections focused on Greek and Latin

literature and language, the results can give guidance for collection

development and maintenance. Of special concern is the continuing purchase of

monographs to support research in classical philology, but the retention of

materials is also important due to the age and languages of materials used by

scholars in this discipline.

Introduction

Citation analysis has been a mainstay in the literature of librarianship

and information science. A search for the term “citation analysis” in Library Literature & Information Science

Index produced by H. W. Wilson results in a list of over 1,600 articles for

the years 1981 to 2012. When combined with the search term “collection

development,” however, the results shrink to less than 60 articles. Outside the

field of librarianship and information science, citation analysis is used in a

variety of fields, especially to determine leading journals, influential

articles, and major authors. A search of PsycInfo

via APA PsycNet yielded over 240 articles containing the phrase “citation

analysis” for the period 1927 until 2012. Even the MLA (Modern Language Association) International Bibliography database includes several articles that

contain the phrase “citation analysis.” In contrast, a search of the L’Année philologique on the Internet

database covering 1924 to 2011 (the latest update) retrieves no articles

specifically on citation analysis within the field of classical studies. L’Année philologique is the primary

database for the literature of the field of classical studies and currently

indexes approximately 1,500 journals.

This research seeks to rectify this lack of research by examining

citation patterns in classical studies, specifically classical philology,

through an analysis of articles in the Transactions

of the American Philological Association, usually referred to as TAPA. Classical philology has a broad

definition which covers most of the fields that are included in the domain of

classics or classical studies including literature, languages, history,

philosophy, art, religion, and material culture. Of specific concern, however,

is the study of literary and philosophical texts produced by the ancient Greeks

and Romans.

Literature

Review

The literature on citation analysis and its variants such as co-citation

analysis has a long and storied history. According to Broadus (1977),

librarians have long used citation analysis for collection building and

management. Similarly, Bowman (1991) argued that citation patterns could be

used as one method for deciding the suitability of specific items for inclusion

in a library’s collection. Of special interest to Bowman were the formats cited

(for example, books and journals), languages of items cited, and the age of

items cited. Many researchers have studied specific fields to determine how

citation analysis can be applied to collection development. For example, Zhang

(2007) examined the field of international relations, determining that

monographs made up almost half the cited materials while journals contributed

almost 40%. The vast majority of items cited were written in English, with

foreign languages accounting for less than 4% of the total citations. Liu

(2007) applied citation analysis to the field of educational psychology. He

specifically studied the clustering of specialties in educational psychology

and stated that studies such as his “can inform librarians doing selection of

journals … to meet their specific needs” (p. 117). In an earlier article,

Hitchcock (1990) examined the use of research materials in a single historical

journal. She wrote:

Citation analysis

is a valid method of measuring the use of materials since it takes advantage of

the author’s attempt to substantiate the findings of the research based on

documented evidence. As a collection development tool, it benefits from the

citation’s function of providing sources of further information on a subject.

It is a reliable method as the data are readily available in print and not

subject to response variables as are questionnaires. (p. 53)

Hitchcock concluded her article, “Libraries can best serve researchers

of state and local history by becoming aware of the researchers’ use of primary

sources, and providing services which will satisfy their information needs” (p.

54). This is also true of researchers in all academic fields.

Budd and Christensen (2003) examined the social sciences to see how

expanding access to electronic information resources had changed citation

patterns. They found that within the eight journals from the social sciences

that they included in their analysis, few electronic resources were cited. In

particular, they found that almost 47% of the citations were to journals and

another 44% were to books. They wrote, “One inference that might be drawn from

this indicator is that, for the time being at least, the academic world adheres

to formal and traditional media for communication” (p. 645).

Several authors have examined the field of classical studies, often in

combination with other fields of the humanities. In a trio of articles, Kellsey

and Knievel (2004), Knievel and Kellsey (2005), and Kellsey and Knievel (2012)

studied citation patterns in various humanities fields, including classics. In

their first article (Kellsey & Knievel, 2004), the primary goal was to

determine the use of foreign languages by examining the citations in

representative journals for a span of 50 years. In total, they counted 16,138

citations from 468 articles in 4 journals from history, classics, linguistics,

and philosophy. For classics, they used the American

Journal of Philology as their source. The results for this journal

indicated that the use of foreign language materials had declined from 1962 to

2002. In 1962, over 45% of all citations were to foreign language materials

while in 2002 slightly over 21% were to foreign language items. In their 2005

article, the authors analyzed 9,131 citations from the 2002 volumes of journals

in eight humanities fields, including classics. Again, citations from the American Journal of Philology were used

as the source of data for the field of classics. This study broadened the scope

of the analysis to include formats of materials studied as well as language.

That particular volume of the American

Journal of Philology yielded 996 individual citations with an average of

39.8 citations per article. Over 76% of the citations were to monographs while

slightly over 33% were to journals. Almost 80% of the citations were to English

language materials. Finally, in their 2012 article, they examined citations

from 28 monographs published by humanities faculty members with the goal of

determining how these scholars accessed the materials they used. Specifically,

they queried whether the sources were owned by the faculty member’s academic

library, how they were acquired (approval or firm order), their average age,

and interdisciplinary usage as determined by the LC classification of the cited

item.

For the field of classics, especially classical philology, two pieces of

research stand out, Tucker (1959) and Dabrishus (2005). Both of these master’s

papers were written at the University of Chapel Hill. Tucker’s goal was “to

ascertain certain of the characteristics of the literature used by researchers

in the field of classical philology” (p. 1) by studying the literature cited in

the Transactions of the American

Philological Association. Among the characteristics he examined were the

form of publication, the age of the literature cited, the specificity of the

citation, and the use of foreign language publications. Tucker’s analysis

included a total of 1,327 citations drawn from 33 articles in two volumes of TAPA, volume 87 (1956) and volume 88

(1957). He only counted those citations to secondary sources, not the primary

sources that were often the focus of the article itself. For example, the

original text of Euripides was not included in the citation analysis, but works

about the text were included.

Specific results from Tucker’s research are discussed below in the results

section. Dabrishus studied the citations included in three classics journals: The Classical Quarterly, Classical Antiquity, and Mnemosyne. Although she focused

primarily on the use of periodicals, she did note that monographs were cited

heavily, accounting for 76% of all citations, while periodicals received only

24% of the citations in her analysis. The three most frequently cited journals

were The Classical Quarterly, Bulletin de correspondence hellénique,

and Transactions of the American

Philological Association. In total, the articles in the three journals

included in the study cited 120 different journals of which over half were

cited more than one time each.

Aims

The overall goal of this research was to study changes over time in the

way scholars have used the literature of classical (Greek and Latin) philology.

Based on previous research, the journal Transactions

of the American Philological Association (TAPA) was used for the analysis and this study attempted to

determine changes over time for the types of materials cited (e.g., monographs

and journals), the languages of the cited materials, the age of the items

cited, and the specificity of the citations. The results of the analyses

provide data which may be used by librarians in making collection development

decisions, especially the allocation of resources for monographs and journals

in classical studies, the discarding of materials which are no longer relevant,

and the placement of materials in storage.

Methods

In order to understand how citation trends in classics have changed over

time, the current research sought to replicate and update the research

performed by Tucker (1959). All citations to secondary sources from articles

published in TAPA for the years 1986

and 2006 were compiled into a spreadsheet. The use of these two years of TAPA helped determine if there had been

significant changes over time in the citation patterns for this specific

journal, especially when compared to the original research which analyzed

citation data drawn from the 1956 and 1957 volumes of TAPA. In addition, using citations from the 2006 volume provided a

way to determine the extent to which scholars in this field cite identifiable

electronic resources (other than journals which, while electronically

available, are usually cited as if they were used in a print version).

Every citation included in each article appearing in the 1986 and 2006

volumes of TAPA was examined and only

those from secondary sources, that is, not the original texts being discussed

in the article itself, were included in the analysis. Citations to original

Greek and Latin texts were, therefore, not included in the analysis. The data

for each citation included the name(s) of the author(s), the title of the

publication, the type or format of publication, the date of publication, the

language of the publication, and the specificity of the citation. In addition,

the age of the citation was determined by subtracting the date of the

publication from the year in which the source article appeared in TAPA. As determined by Tucker, the type

of publication included the following formats: book/monograph,

journal/periodical, annual/yearbook, encyclopedia/dictionary, Festschriften,

dissertation/thesis, and other. The current research added electronic sources

for the 1986 and 2006 articles. Languages of citations included English, German,

French, Italian, Latin, Greek, and Spanish. Following the work of Tucker,

specificity focused on the length of the citation, i.e., 1 page, 2-10 pages,

over 10 pages, an entire article (of a journal, annual, etc.), an entire book,

a book chapter, and other. All citations to secondary materials were entered

into the analysis, including ibid. and op. cit. citations.

Results

In his research, Tucker (1959) did not separate his results by year.

Thus, in the following tables and discussion, his results are given as he

presented them, consolidating both years of his study into one set of data. In

the two volume years of TAPA that he

included in his study, Tucker examined 1,327 citations drawn from 33 articles,

an average of 40.21 citations per article. As shown in Table 1, the current

research examined 34 articles and 3,323 citations. In 1986, there were 20

articles that included 1,421 citations, an average of 71.05 citations per

article. By 2006, the number of articles had declined to 14, but the total

number of citations had ballooned to 1,902, an average of 135.86 citations per

article. Thus, there is a statistically significant increase in the average

number of citations per article between the 1956/57 and the 1986/2006 data

(t=4.542, p<.001). In fact, there is also a statistically significant

difference between the 1986 and the 2006 average number of citations per

article (t=-2.598, p=.014). These results show that the number of items cited

by authors of articles had grown considerably between 1956 and 2006. More

recent authors cited more than 3 times as many sources as authors during the

1950s.

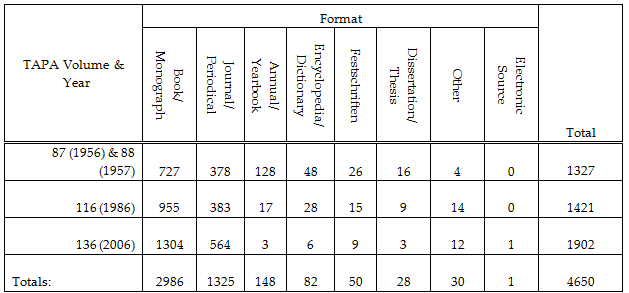

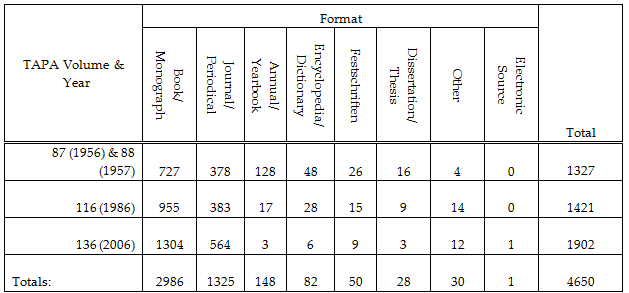

Table 2 provides a breakdown in the types of publication cited in the

examined articles. A chi-square test results in a statistically significant

result (chi square=358.63, p<.001, df=12) indicating that the types of

publications cited had changed significantly over the time span. In 1956/57,

books and monographs accounted for 54.8% of the citation. This percentage grew

to 67.2% in 1986 and 68.6% in 2006. Citations to journals and periodicals

remained fairly stationary (1956/57: 28.5%; 1986: 26.9%; and 2006: 29.7%).

Major changes are observed for the remaining types, except for other. Citations

to annuals and yearbooks fell from 9.6% of citations in 1956/57 to only 0.2% in

2006. Similarly, citations to encyclopedias and dictionaries fell from 3.6% in

1956/57 to 0.3% in 2006. Citations to Festschriften and dissertations likewise

fell dramatically over the timespan of the study. There is only one citation to

an electronic resource in 2006, although by then the Internet and World Wide

Web had been publicly available for well over a decade. This may be misleading,

however, since many journals in the field of classical studies, especially

philology, had been available electronically for many years prior to 2006. The

authors may have used electronic sources, but not cited them as such.

Table 1

Citations per TAPA Volume

|

TAPA Volume & Year

|

Number of Articles

|

Number of Citations

|

Average Citations per Article

|

|

87 (1956)

&

88 (1957)

|

33

|

1327

|

40.21

|

|

116

(1986)

|

20

|

1421

|

71.05

|

|

136

(2006)

|

14

|

1902

|

135.86

|

|

Total

|

67

|

4650

|

69.4

|

Table 2

Format of Materials Cited

** “Other” includes newspapers, conference

proceedings, and government documents

A total of 935 different books or monographs were cited by the 1986 and

2006 articles. In 1986 there were 387 different books cited, while in 2006

there were 562. Several books were cited in both years. Tucker, unfortunately,

did not list the total number of different books cited but only included the

total number of citations to books.

Of particular interest are the journals and periodicals which were cited

within these articles. Table 3 gives a breakdown of the ten titles which

received the greatest number of citations for each year included in the study.

The chart is arranged alphabetically with the number of citations given to that

specific journal during each of the study years given in the columns. As can be

seen, of the eighteen journals listed, only four were in the top ten for all

three years: American Journal of

Philology, Classical Philology, Hermes, and Transactions of the American Philological Association. Four others

were in the top ten for two years: Arethusa,

Classical Journal, Classical Quarterly, and Journal of Hellenic Studies. Of these, Arethusa did not begin publication until

1968, well after Tucker’s study. Of the top 10 journals cited in the 1956 and

1957 volumes, only one (Byzantinische

Zeitschrift) was not cited by any of the articles in the later volumes of TAPA. Tucker does not provide a listing

of all the journals cited during the years of his study, but for 1986 and 2006

a total of 119 different journals received citations. In 1986, there were 93

different journals cited and in 2006, 101 different journals were cited. Thus,

it is evident that scholars in the field of classical philology cast a wide net

when utilizing the research literature.

The language of the sources of citations also changed significantly over

time (chi-square=601.40, p<.001, df=14). Table 4 shows that English was, by

far, the most frequently cited language for all years, accounting for 67.5% of

all citations included in the study. In contrast, for the years 1956 and 1957

English accounted for less than half of the citations while German received

31.1% and French 11.3%. By 1986, German and French witnessed dramatic declines

with German accounting for 23.9% and French for 6.3% while English grew to

67.2%. For the 2006 articles, English grew even more, accounting for 83.2% of

the citations. German and French continued to decline (8.4% and 3.3%

respectively) and Italian increased slightly in comparison to the 1986

citations (3.0% in 2006 compared to 2.5% in 1986), yet did not approach the

7.7% in 1956 and 1957.

The level of specificity of citations also changed significantly over

time (chi-square=168.13, p<.001, df=12). As shown in Table 5, citations to

a single page remained fairly steady over time, while citations to 2-10

pages declined as a percentage of the total citations. The major changes were

in the number of citations to entire books and to book chapters, both of which

grew greatly over the period.

Finally, the study examined the age of the citations. Table 6 gives the

age breakdown of citations using the time spans originally established by

Tucker in his research. The age of the citation was determined by simply

subtracting the publication year of a citation from the volume year of TAPA. For example, if an item being

cited by an article in volume 136 (2006) was published in 1997, the age of the

citation was recorded as 9 years old. In contrast to the other changes noted

above, the average age of citations remained very stable over time. For the

1956-1957 citations, the average age was 25.23 years. For the 1986 citations,

the average age was 24.53 years and for 2006, the average age was 24.63 years.

Discussion

Table 3

The Ten Most Cited Journals by TAPA Volume

|

Journal

|

Vol. 87

(1956)

& 88

(1957)

|

Vol. 116

(1986)

|

Vol. 136

(2006)

|

|

American

Journal of Archaeology

|

|

24

|

|

|

American

Journal of Philology

|

35

|

16

|

23

|

|

Arethusa

|

|

13

|

22

|

|

Byzantinische

Zeitschrift

|

9

|

|

|

|

Classical

Antiquity

|

|

|

17

|

|

Classical

Journal

|

31

|

12

|

|

|

Classical

Philology

|

12

|

11

|

69

|

|

Classical

Quarterly

|

12

|

29

|

|

|

Classical

Review

|

11

|

|

|

|

Greece

& Rome

|

|

|

19

|

|

Harvard

Studies in Classical Philology

|

|

24

|

|

|

Hermes

|

17

|

36

|

18

|

|

Journal

of Hellenic Studies

|

|

13

|

35

|

|

Philologus

|

12

|

|

|

|

Phoenix

|

|

|

24

|

|

Proceedings

of the Cambridge Philological Society

|

|

|

17

|

|

Rheinisches

Museum fur Philologie

|

11

|

|

|

|

Transactions

of the American Philological Association

|

63

|

19

|

38

|

Table 4

Language of Citations

|

TAPA Volume & Year

|

Language

|

Total

|

|

English

|

German

|

French

|

Italian

|

Latin

|

Greek

|

Spanish

|

Other

|

|

87 (1956) &

88 (1957)

|

604

|

413

|

150

|

102

|

44

|

9

|

1

|

4

|

1327

|

|

116 (1986)

|

955

|

340

|

89

|

35

|

1

|

1

|

0

|

0

|

1421

|

|

136 (2006)

|

1583

|

160

|

63

|

58

|

18

|

15

|

5

|

0

|

1902

|

|

Total

|

3142

|

913

|

302

|

195

|

63

|

25

|

6

|

4

|

4650

|

Table 5

Specificity of Citations

This study of citations to the literature of classical philology support

several observations. Authors of articles included in TAPA rely heavily not only on the literature of the field of

classical philology, but also on the literature of related fields such as

history, philosophy, and archaeology, as shown in the growth in the variety of

items cited. According to the articles included in the study, the average

number of citations more than tripled from 1956 and 1957 until 2006, indicating

a greater reliance on previously published literature. It is difficult to

speculate on all the reasons for this increase in the number of citations,

especially considering the similarity in the length of the articles over the

years, although the training of scholars in the humanities emphasizes the

necessity of building upon the work of previous scholars. The availability of

materials, especially journals through a variety of electronic databases and the

ease of interlibrary loan, may have made resources more readily available to

scholars, thus increasing the amount of material used in more recent research.

The types of materials cited, while similar, did show statistically

significant changes. Specifically, the citations to books increased

dramatically, from 54.8% of the total citations in 1956 and 1957 to 68.6% in

2006, although this is still less than the 76% reported by Dabrishus (2005).

Such growth in the number of citations to monographs is a surprising finding

when one considers the growth in the use of journals shown by most scholarly

fields. The finding does underscore the monographic nature of the field of

classical studies and the continuing importance of books to scholars within the

humanities.

Within TAPA articles,

citations to journals remained fairly steady at slightly less than 30%. The use

of other materials, such as encyclopedias and Festschriften, all declined,

although their numbers represented a relatively small percentage in the types

of materials cited during all years. One surprising result was the lack of

specific citations to electronic resources, especially considering the

tremendous growth of websites, e-only journals, online encyclopedias, etc. Only

one purely electronic resource was identified in this study, although many of

the journals and monographs could have been accessed through electronic

databases.

Table 6

Age of Citations

|

Age of

Citations

|

|

Age in

Years

|

Vol. 87

(1956) & 88 (1957)

|

Vol. 116

(1986)

|

Vol. 136

(2006)

|

Total

|

|

0-5

|

283

|

292

|

164

|

739

|

|

6-10

|

181

|

203

|

352

|

736

|

|

11-15

|

96

|

161

|

345

|

602

|

|

16-20

|

144

|

233

|

256

|

633

|

|

21-25

|

85

|

126

|

162

|

373

|

|

26-30

|

95

|

63

|

139

|

297

|

|

31-35

|

77

|

43

|

106

|

226

|

|

36-40

|

46

|

30

|

110

|

186

|

|

41-45

|

39

|

14

|

73

|

126

|

|

46-50

|

55

|

21

|

50

|

126

|

|

51-75

|

138

|

124

|

73

|

335

|

|

76-100

|

39

|

88

|

45

|

172

|

|

100+

|

47

|

20

|

27

|

94

|

|

No date

|

2

|

3

|

0

|

5

|

|

Total

|

1327

|

1421

|

1902

|

4650

|

The analyses also show that a wide variety of books and journals were

cited. Thus, for developing a collection to support research in classical

philology, books remain an important mainstay for scholarly work. Such books

include not only commentaries on specific classical authors, but also works on

art, archaeology, literature, and philosophy. The array of journals consulted

is also very broad, although there is a fairly small core of journals which

received heavier use. Thus, librarians have evidence that providing the core

set of journals will provide a large proportion of the materials actually cited

by classical scholars in their research. This result can help determine how to

spend the scarce resources available for collection development.

The utilization of foreign language materials has greater implications

for collection development and maintenance. In 1956 and 1957, English language

materials accounted for only about half of the citations. By 2006, English

materials represented 83.2% of all citations. During this time frame, the use

of foreign language materials declined precipitously. For example, German

language materials declined from 31.1% of all citations to 8.4% and French

declined from 11.3% to 3.3%. These changes, however, may be deceiving, since

many materials, especially books, may have been translated into English from

the other languages in more recent years. Still, these changes do show that

scholars in the field of classical philology rely heavily on materials in

English. These results mirror those found by Kellsey and Knievel (2004) and

Knieval and Kellsey (2005), although the American

Journal of Philology cited a higher proportion of foreign language

materials than did TAPA. As a result

of such evidence, for many libraries collection development in the field of

classical philology should focus primarily on English-language materials,

although the evidence also reiterates the need for access to a wide variety of

materials in other languages which may be provided through interlibrary loan or

databases of foreign-language journals.

The specificity of citations has also changed over time. The main change

is the dramatic increase in the number of citations to whole books and to

chapters in books. This mirrors the results for the types of materials cited

and shows an increased usage of monographs, indicating that the demand for

scholarly monographs in classics continues to be high. Tucker (1959) says, “The

longer, more exhaustive treatment which a book can afford a topic could be a

considerable factor in the most frequent choice of this form” (p. 16).

The most striking result of the present study is the consistency in the

average age of citations within this field of approximately 25 years old. As

Tucker (1959) notes, “The researcher in this field perhaps does not feel so

constrained to consult the most current literature” (p. 14). The field of

classics in its broadest sense has a long history, stretching back centuries,

and obsolescence of scholarly ideas is low. As can be seen from the age

analysis, even materials from the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries are

still cited by scholars. Such citation patterns have major implication for retention

policies. If scholars are regularly using such older materials, these books and

journals need to be available. This could call into question the weeding of

older books and journals or their placement in remote storage facilities.

Digitization of these older materials could also help solve the problems of

storage.

Conclusions

The study of citation patterns can provide the scholar and the librarian

with varied insights into selected fields. This study sought to replicate and

expand an earlier study and provides useful information on how scholars in the

field of classical philology use sources in their research. The results, of

course, are limited to only one scholarly field and cannot be generalized to

other subjects. Similar methodology, however, has been used frequently in the

study of other fields. The results from this study and others can help

librarians in their pursuit of providing materials needed by scholars for their

research. Of special concern is the retention of materials. In the case of classical

philology, scholars make use of materials from a wide time span written in a

variety of languages, although more recent research has relied increasingly on

English language materials. In addition, they are heavy users of monographs,

yet they still use a wide array of journal titles. Thus, such materials need to

be retained in research library collections. Unlike other fields, especially in

the sciences, which rely more heavily on current journals, classics continues

to rely on both monographs and journals and ideas expressed in older materials

can still have immense relevance to current research. As a result, librarians

cannot make blanket decisions for retaining materials, such as format or age.

They must consider the nature of the use of materials by subject discipline.

References

Bowman, M.

(1991). Format citation patterns and their implications for collection

development in research libraries. Collection

Building, 11(1), 2-8.

Broadus, R.

N. (1977). The application of citation analyses to library collection building.

Advances in Librarianship, 7,

299-335.

Budd, J.,

& Christensen, C. (2003). Social sciences literature and electronic

information. portal: Libraries and the

Academy, 3(4), 643-651. doi: 10.1353/pla.2003.0077

Dabrishus,

M. (2005). The forgotten scholar:

Classical studies and periodical use (Unpublished master’s thesis).

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC.

Hitchcock,

E. R. (1990). Materials used in the research of state history: A citation

analysis of the 1986 Tennessee Historical Quarterly. Collection Building, 10(1/2),

52-54.

Kellsey, C., & Knievel, J. E. (2004). Global English in the

humanities? A longitudinal citation study of foreign-language use by humanities

scholars. College & Research Libraries, 65(3), 194-204.

Kellsey, C., & Knievel J. (2012). Overlap between humanities faculty

citation and library monograph collections, 2004-2009. College & Research Libraries, 73(6), 569-583.

Knievel, J.

E., & Kellsey, C. (2005). Citation analysis for collection development: A

comparative study of eight humanities fields. The Library Quarterly, 75(2),

142-168. doi:10.1086/431331

Liu, Z.

(2007). Scholarly communication in educational psychology: A journal citation

analysis. Collection Building, 26(4), 112-118.

Tucker, B.

R. (1959). Characteristics of the

literature cited by authors of the Transactions of the American Philological

Association, 1956 and 1957. (Unpublished master’s thesis). University of

North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC. doi:oclc/23993605

Zhang, L.

(2007). Citation analysis for collection development: A study of international

relations journal literature. Library

Collections, Acquisitions, & Technical Services, 31(3/4), 195-207. doi.org/10.1016/j.lcats.2007.11.001

![]() 2013 Crawford. This is an Open Access article

distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 2.5 Canada (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.5/ca/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

2013 Crawford. This is an Open Access article

distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 2.5 Canada (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.5/ca/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.