Introduction

Rider University, located

in Lawrenceville, NJ, is a private, coeducational university with 5,500

students, offering 69 undergraduate programs in business administration,

education, liberal arts, the sciences, fine and performing arts, counseling,

and leadership, plus 25 Masters level degrees. Librarians at the Franklin F.

Moore Library (also known as the Moore Library) have established an active

library instruction program, working with teaching faculty to integrate

information literacy (IL) into their courses for the past decade. Following the

emphasis placed on assessment by the Middle States Commission on Higher

Education, the accrediting body for Rider University, the Moore Librarians have

been involved in assessment since 2002.

The learning objectives for

information literacy are based on the Association of College and Research

Libraries (ACRL) Information Literacy Competency Standards for Higher Education

(American Library Association, Association of College and Research Libraries,

2000). This study reports on the Moore Library’s assessment program that

measured students’ IL levels in two academic years (2009-2010 and 2010-2011) on

the first two ACRL IL standards, which include the same IL learning objectives

for students at Rider University. These objectives contain the basic

information literacy competencies and are appropriate for lower division

undergraduates:

1. The information

literate student determines the nature and extent of the information needed.

Students will identify a variety of types and formats of potential sources of

information.

2. The information

literate student accesses needed information effectively and efficiently.

Students will recognize controlled vocabularies; illustrate search statements

that incorporate appropriate keywords and synonyms, Boolean operators, nesting

of terms, and truncation, refining the search statement when necessary; and

determine the most appropriate resources for accessing needed information.

Research Questions

Most of the ILI sessions

occur in the Library’s two computer labs. The topics of the assignments and

areas of study range widely from business to humanities, social sciences,

sciences, and technology. The librarians teach sessions for their liaison

departments and share teaching responsibilities for the core Research Writing

and the Honors Seminar classes.

The current study assessed

the knowledge of students of all class years for the first two IL objectives in

the academic year 2009-2010. For the 2010-2011 academic year, identical pretests

and posttests combining these two IL objectives were used to assess the impact

of ILI on students’ learning in the Research Writing course. Our research

questions for this study include:

- Do students’ possess different levels of knowledge and skills for

the two IL objectives?

- Do different student populations [freshmen (1st year), sophomores

(2nd year), juniors (3rd year), seniors (4th year),

Honors students, and students in different areas of study] possess

different levels of IL?

- Are students’ performances on the IL pretest associated with the

frequency of prior ILI received?

- Do students improve their IL skills after the ILI?

Literature Review

Several approaches to

assessing undergraduate students’ acquisition of information literacy skills

have been documented. This literature review will discuss these different methods

used, including the pre and posttest system used by the authors.

Small-scale, inexpensive

assessment approaches

Some assessment techniques

that are on a smaller and less expensive scale include the one-minute paper

(Angelo & Cross, 1993; Choinski & Emanuel, 2006; Cunningham, 2006), an

attitude survey, observational assessment, a faculty assessment survey

(Cunningham, 2006), short quizzes given during a one-credit course (Hufford,

2010), online tutorials (Fain, 2011; Heimke & Matthies, 2004; Johnson,

2009; Lechner, 2005; Merz & Mark, 2002; Tronstad, Phillips, Garcia, &

Harlow, 2009), interviews (Julien & Boon, 2004) and, in one case,

interviews conducted by anthropologists (Kolowich, 2011).

Authentic Assessment

Authentic assessment

depends on students’ actual performance on tasks such as an annotated

bibliography, submitted research papers, bibliographies, and worksheets as

discussed by Oakleaf (2011) and Brown and Kingsley-Wilson (2010). Rubrics are

designed to assess these types of documents and provide a systematic way to

determine how well students have achieved the learning objectives. McCulley

(2009) and Rogers (2001) discuss “Reflective Learning” where students think

about their processes of learning through the use of portfolios and journals as

a way to help them become better learners.

Standardized Testing

Other types of assessment

include standardized testing formats used to assess baseline competencies among

undergraduate students. The Educational Testing Service (ETS) and Kent State

University have developed standardized tests for measuring student information

research skills using scenarios: the iSkills exam (Katz, 2007; Katz &

Macklin, 2007), and Project SAILS, (Radcliff, Salem, O’Connor, Burhanna, &

Gedeon, 2007; Rumble & Noe, 2009) respectively. These tests allow

large-scale aggregation of data amongst many institutions, but can be

expensive, time consuming, and would be difficult to use for pretesting and

posttesting. However, these tests can be used to assess gains over time to

determine trends.

Pre and Posttest Methods

It is evident that the

library literature details a wide variety of mechanisms for assessing IL

skills. Moore Librarians selected the pretest and posttest method for obtaining

a sense of students’ understanding of different resources and search strategy

skills and confirm or disprove anecdotal evidence of such skills. These tests

are easy to construct using online forms via Google Docs; they can be

administered quickly, and data they generate are easily downloaded and analyzed

(Hsieh & Dawson, 2010). This procedure allows librarians to document

students’ IL skills and to measure gains over time.

There are instances of the

use of pretests and posttests in credit courses. In a one-credit course taught

at Texas Technology University, students were given a pretest at the start of

the semester and a posttest at the very end of the semester. Both tests were

identical and some questions had multiple answers. Despite IL skills taught

over a 14 week period, students did not do as well as expected in the posttest

(Hufford, 2010). In another example, a three-credit class conducted at the

University of Rhode Island used pretests and posttests to determine student

learning of Boolean operators (Burkhardt, 2007). The librarians were

disappointed in the small increase between these two test scores. Gandhi (2004)

detailed the assessment of a five-session model for library instruction and

found students learned more than after a one-shot session. However, this may

not be a very practical approach because of the many demands on the librarians’

times. Further, faculty members are usually very reluctant to give up class

time for such sessions.

About 85 % of 60- to

90-minute course-integrated ILI sessions taught by the Moore librarians at

Rider University are single-sessions, typical ILI offered in many academic

libraries in the United States (Merz & Mark, 2002). Most of the literature reviewed for this

paper involves one-shot instruction sessions. A survey developed by librarians

at the University of Northern Texas used a software system that tracked

websites used by students during their assessment; four questions were used as

a pretest and posttest. This survey demonstrated that ILI helped students and

provided information on weaknesses such as subject searching in the online

catalog (Byerly, Downey, & Ramin, 2006). A review paper describing the

pretest/posttest techniques raised concerns about using identical sets of

questions for both tests, and the problem with the span of time placed between

these two tests as the major factor in determining retention (Emmett &

Emde, 2007). At Cornell University, the posttests indicated improvement in IL

skills but the authors stated that a posttest later in the term would be needed

to determine the amount of retention of the material (Tancheva, Andrews &

Steinhart, 2007). Julien and Boon (2004) did just that. The posttest was given

immediately after a library session and a post-posttest given to students three

to four months later. Students showed a decline from the posttest to the

post-posttest. This indicates that information is not retained well, and

suggests the need for reinforcement of IL concepts throughout the semester.

Fain (2011) outlined a

five-year longitudinal study using pretests and posttests administered by

teaching faculty instead of librarians. The author enlisted the help of

Psychology faculty for the statistical analysis of the data, similar to what

Moore Librarians have done. In addition, the study emphasized the impact of the

assignment on teaching information literacy skills, i.e., if journal articles

are required but not books, then assessment questions related to using an

online catalog or types of books will not be taught by librarians. This would

affect the outcomes of any IL assessment that asks about resources such as

books and skills using the online catalog.

Surveys have frequently

been used to assess students’ opinions or ask about their satisfaction with IL

instruction (Matthews, 2007). Freeman and Lynd-Balta (2010) and Knight (2002)

described studies using pretests and posttests to assess students’ confidence

levels in information literacy skills. However, these types of studies do not

demonstrate students’ knowledge or capability to apply learned IL skills. As illustrated

by Dawson and Campbell (2009), computer and information literacy skills are not

equivalent. Students may exhibit confidence in their search skills because of

their familiarity with Google and social media. This may be a consequence of

students confusing their computer skills with information literacy skills.

Method

Participants

Participants were

undergraduate and graduate students at Rider University sampled from the fall

2009 semester through the spring semester of 2011. For the first year of the

study (academic year 2009-2010), all students attending ILI sessions in the

Moore Library computer labs were assessed to establish a baseline IL level of

all students. In the second year (academic year 2010-2011), instead of testing

students in all ILI sessions, the librarians narrowed the study population to

students in the Research Writing and

the Honors Seminar courses. This was done because the IL objectives matched the

courses’ objectives well. In addition, 7 of the Research Writing instructors

requested a follow-up session after the first ILI, allowing the use of

posttests in 15 classes to determine learning outcomes from their previous ILI.

Numbers of participants are

shown in Table 1. Participants for the fall 2009 and spring 2010 semesters

included all who received ILI at the Moore Library. Of these 1,986 students,

560 were freshmen, 310 were sophomores, 420 were juniors, 338 were seniors, 313

were graduate students, and 45 were reported as “other.” Students in subsequent

cohorts (fall 2010 and spring 2011) included students from core writing courses

only. Students not in the Honors program were enrolled in Research Writing

(CMP125) course. The fall 2010 cohort consisted mainly of sophomores (129 of

177 students), whereas freshmen composed the majority in the spring 2011 cohort

(362 of 436 students).

Students in the

Baccalaureate Honors Program (BHP) have GPAs of 3.5 or better. They scored

higher in the standardized college entrance exam Scholastic Aptitude Test (SAT)

with Critical Reading and Math scores of at least 600 and Writing score of at

least 550 (BHP, n.d.). The Honors students typically take the BHP-150 Honors

Seminar in the spring semester during their freshmen year and therefore, almost

all (121/122) were freshmen. This group did not receive follow-up sessions.

Information Literacy

Instruction Sessions

All sessions took place in

the computer labs of the Moore Library and were conducted by one librarian.

Classes typically included up to 25 students. The basic IL concepts in the

first two IL objectives are applicable in any ILI. Some concepts might be introduced

more thoroughly than others in a session depending on the requirements of the

assignments and students’ topics. For example, when an assignment called only

for journal articles, librarians would demonstrate searching for articles in

selected databases but not searching for books in the online catalog. Book

sources might be merely mentioned in such a session. On the other hand, some

concepts and skills such as search logic, methods of searching for articles

using the library subscription databases, and locating the library’s

periodicals were emphasized in almost all sessions.

The IL content the

librarians taught was not limited to the IL concepts represented in the tests.

For each session, the librarians provided handouts that included a combination

of content outlines and step-by-step instructions for their sessions. In summer

2010, the Library began subscribing to LibGuidesTM for research

guides, with Moore librarians gradually developing their instruction content in

these online guides and using them in ILI. Librarians’ teaching styles varied

and individual librarians engaged students and faculty differently in their

sessions. Nevertheless, most ILI consisted of lecture, search demonstration,

and hands-on time during which librarians monitored and coached students in

researching their topics. In the 2010-2011 academic year, of the 20 CMP-125

faculty members, 7 requested a follow-up session after the first ILI to allow

students more instruction, hands-on time, and coaching from the librarians. As

the result, 15 of the 39 classes (38%) had follow-up sessions.

Table 1

Numbers of Students and

Tests Used for Each Cohort

|

|

N

|

Test

|

Pre1

|

Pre2

|

Post1

|

Post2

|

|

Fall 2009

|

1106

|

A

|

X

|

----

|

----

|

----

|

|

Spring 2010

|

880

|

B

|

----

|

X

|

----

|

----

|

|

Spring 2010

Honors

|

55

|

B

|

----

|

X

|

----

|

----

|

|

Fall 2010

|

177

|

AB

|

X

|

X

|

----

|

----

|

|

Fall 2010

Pre-Post*

|

44

|

AB

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

|

Spring 2011

|

436

|

AB

|

X

|

X

|

----

|

----

|

|

Spring 2011

Pre-Post*

|

115

|

AB

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

|

Spring 2011

Honors

|

67

|

AB

|

X

|

X

|

----

|

----

|

Note: An X denotes

administration of the test. Pre1 = Pretest for Objective 1, Pre2 = Pretest for

Objective 2, Post1 = Posttest for Objective 1, Post2 = Posttest for Objective

2, Test A includes 5 questions for Objective 1 in Appendix A; Test B includes 5

questions for Objective 2 in Appendix B. Pre-Post* = Pre- and Posttest matching

records.

Test Development

Time is at a premium in the

ILI sessions if both instruction and hands-on time are to be included,

therefore, the assessment instrument had to be short and easily accessible to

students in the library labs. In fall 2009, an online test with five

multiple-choice questions (see Appendix A) was developed to assess the IL

abilities of students on the first IL objective – identifying a variety of

sources. The test was developed according to the best practices guidelines for

generating tests/surveys outlined by Radcliff, Jensen, Salem, Kenneth, and

Gedeon (2007) and by adapting test questions used elsewhere (Burkhardt, 2007;

Goebel & Mandeville, 2007; Mery, Newby, & Peng, 2011; Schroeder &

Mashek, 2007; Staley, Branch, & Hewitt, 2010). It was piloted on student

workers at the Moore Library to ensure that the language in the test was clear

to college level students. The librarians installed the test online using Google

Docs. In spring 2010, a second test (see Appendix B) was developed in the same

fashion for the second IL objective on constructing search queries.

In the second year of the

study, the librarians aimed to measure student learning in the ILI sessions by

developing identical pretests and posttests. The two sets of questions used in

2009-2010 were combined into a single set of questions used in 2010. Following

use of this 10-item test in the fall of 2010, the Moore librarians shared the

fall 2010 results with a group of teaching faculty and received feedback on the

test in January 2011. Consequently, in spring 2011, the wording of several

questions was modified to make them clearer without changing the IL concepts

assessed. The changes are noted under each question in the Appendices.

In addition to the

questions regarding IL objectives, demographic questions were included on all

versions of the first- and second-year tests. These questions included the

course number, class year (freshmen, sophomore, junior, senior, graduate

student, or other), major area of study (humanities, business, education,

science, social science, undeclared, or other), the number of prior library

instruction sessions attended (on spring 2010 and later versions), and a

four-digit identifying code (e.g., ID number) for matching pretests and

posttests in the fall 2010 and spring 2011 cohorts.

Procedure

As students arrived for

their sessions at the library class labs, they were instructed to take the

online pretest. Students had until five minutes into the scheduled session time

to take the test. Those arriving after that time did not take the test.

Students then completed the ILI session and departed. In the fall of 2010 and

spring of 2011, 7 out of 20 instructors of Research Writing (CMP125) classes

had their classes return for a follow-up library session to receive additional

instruction and hands-on time. These students again were tested as they arrived

for their session and up to five minutes into the scheduled session time. The time

from the first session to the follow-up session varied, but averaged

approximately three weeks.

Design & Analysis

Analyses comprised a series of one-way and factorial analyses of

variance ANOVAs for the focal hypotheses. The REGW-q multiple comparison procedure was used. In addition, chi-squared

tests of association and McNemar’s Test were used for analyses involving

nominal scale measures. The Type I error rate for all tests was .05. Eta, a

measure of nonlinear relationship, was used as a measure of effect size.

Independent variables were

class year (freshmen, sophomore, junior, senior, graduate student), area of

study (humanities, science, social science, education, business, undeclared,

other), course type (core, Honors), IL objective (1, 2), and test (pretest,

posttest). Additionally, the number of prior IL sessions was used as a

correlate of performance for certain cohorts who were asked to report this

information. The dependent variable was the number of questions answered correctly

(of 5) for each learning objective.

Results

In this section, a

discussion of the impact of the question revision in spring 2011 leads to the

combined data that revealed findings of the pretests in both years.

Performances on the two IL objectives were examined separately. Comparisons

were made for the cohorts by semester, class year, course (including Honors

program), major area of study, and frequency of prior ILI. Following the

pretests results were the comparisons of students’ matching pretest and

posttest records in fall 2010 and spring 2011. Findings include students’

learning outcomes on the whole, by objectives and by questions.

Impact of Revised

Questions in Spring 2011

After receiving

feedback from some class faculty on the test results, six questions were

revised (Q2, 3, 5, 6, 7, and 10) in spring 2011 to make the questions clearer

to students without changing the IL concepts (changes are indicated in the

Appendices under each original question). Scores for the original test and

revised test were compared. Only the questions with scores that varied largely

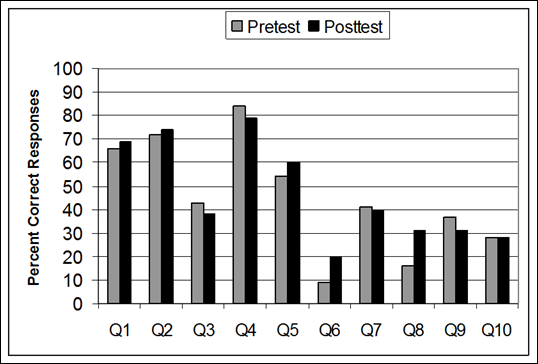

from the previous year were examined for the impact of the revision (see Figure

1). Only questions 2 and 3 yielded results warranting notice.

The decline in

scores by almost 10% in Q2 indicated that the change from “A library’s

database/index” to “A database such as Academic Search Premier” did not help

more students to choose this answer. The reason behind the change was that

perhaps some students did not understand the database/index reference, but they

might be familiar with “Academic Search Premier.” The lower scores in the

revised version indicated that probably fewer participants recognized this

database’s name and therefore fewer chose it.

Question 3 asked

which source one should use to search for background information on an

unfamiliar topic. The question changed from “What's the first thing you should

do to get started?” to “What's the best way to get an overview of this topic?”

The correct answer changed from “Find out some basics on watersheds from an

encyclopedia” to the same answer but included both print and online versions.

The revision moved 16% more participants in the spring to choose “encyclopedia

(online or print),” but the majority (52.8%) still chose the Web for their

answer. The preference of most participants remained the same in both

semesters. On the whole, the minor revisions to the questions in spring 2011

had minimal impact on the results because the highest scores received by the

participants – Q4, Q2, Q1, Q5 in this order, and the lowest scores – Q6, Q8,

Q10, were the same in both semesters and not altered by the question revision. For

this reason, subsequent analyses combined data from the two versions of the

test.

Pretest

IL Objectives. The pretest data revealed that the participants performed significantly

better on IL Objective 1 (Q1-Q5) than on Objective 2 (Q6-Q10), F(1,629) = 143.01, p < .001, eta = .43.

This effect of objective did not interact with year, major, or cohort.

Differences across semesters. For Objective 1,

there were no significant differences across semesters, (F(2,1784) = 1.23, p =

.29, eta = .03) . For Objective 2,

the spring 2011 cohort (Mean (M) =

1.43, SD = 1.05) scored higher than

the fall 2010 (M = 1.15, SD = 1.10) and spring 2010 (M = 1.29, Standard Deviation (SD) = 1.12) cohorts, F(2,1558) = 6.65, p = .001, eta = .09. However, this difference was small (eta = .09) and more

a function of the large sample size than a meaningful difference across

cohorts. For this reason, cohorts were combined in subsequent analyses.

Figure 4

Percentage of students with

each indicated number of prior ILI session by class year.

Figure 5

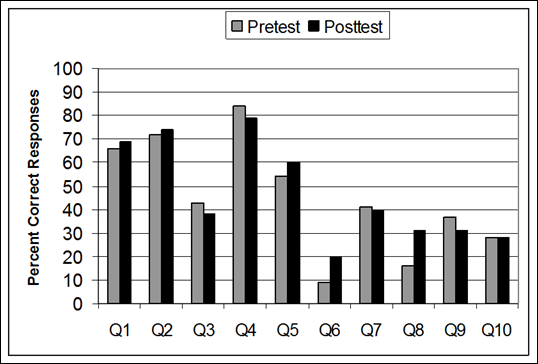

Percentage of

correct responses for each question on the pretest and posttest 2010-2011.

McNemar's Tests were

performed to determine whether accuracy rates varied across tests (pretest vs.

posttest) for each question. Significant increases in accuracy were seen only

for questions 6 (subject search in the catalog, p = .003) and 8 (truncation, p

< .001), even though the posttest scores for both questions were still rather

low. These increases were evident in both semesters. The differences between

the pretests and posttests for the other questions were not significant (see

Figure 5).

For the first IL

objective on identifying a variety of sources (Q1 to Q5), participants

performed the best in differentiating scholarly journals from popular magazines

(Q4). They did relatively well on the purposes of the catalog and the library’s

databases (Q1 & Q2). More than half of the population knew how to find the

library’s full-text journals (Q5). Less than half of the participants would use

encyclopedias to search for background information of an unfamiliar topic (Q3).

Most chose to use a Web search engine for this purpose.

Among the five

questions on Objective 2, participants performed the best on the combination

use of Boolean AND and OR (Q7) with around 40% accuracy rate. They received the

lowest scores on using subject search to find books on the critiques of

Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet in

the online catalog (Q6). More of them would search by

title and by keyword, and very few chose the correct answer, “By subject.” The

posttest scores of this question improved significantly from 10% to 20%.

The tests revealed

further that a great majority of participants were unfamiliar with the use of

truncation (Q8) and the Boolean connector OR (Q9). Very few would consider

using books for a reliable and thorough history on a common topic (Q10). Most chose

to use scholarly journals.

Discussion

Do students’ possess different levels of knowledge and skills for the

two IL objectives?

Participants had higher

scores on the first IL objective than the second IL objective, indicating that

although a majority of Rider students could identify a variety of sources, few

could construct their searches efficiently using these resources.

Do different student populations (class

years, Honors students, area of study) possess different levels of IL?

Faculty members

often assume that students have received their IL training before entering

their class, and expect students to know how to search for information

(Kolowich, 2011; Lindsay et al., 2006). The finding that upperclassmen

performed no differently than their lower division counterparts defies the

assumption and raises an important question about the long-term effectiveness

of the ILI that students receive in and prior to college.

The Honors group,

composed mainly of second semester freshmen, demonstrated higher IL levels than

their peers. It is worth noting that two other studies found positive

correlations between students’ IL levels and their GPAs (McDermott, 2005;

Silvernail, Small, Walker, Wilson, & Wintle, 2008). Do these findings

suggest that the Honors students are efficient in doing research and would not

need IL training? The average pretest scores of 67% on the first objective and

38% on the second objective for this group suggest that they have ample room

for improvement, especially on the second objective (search queries), and could

benefit from IL instruction. The findings of Johnson, Anelli, Galbraith, and

Green (2011) agree with those of the present study: their Honors students

demonstrated the same problems as the others in locating the library’s

resources.

As explained earlier, the

areas of study were broadly defined and do not necessarily correspond to the

participants’ majors. The findings revealed that the humanities and science

students scored higher than business students. Additional research is needed to

determine whether students perform better on discipline-specific IL concepts

than on general IL concepts. One business librarian found no such correlation

(Campbell, 2011) for her business students. In the future, other researchers

may wish to investigate students’ IL in relation to their majors.

Are students’ performances on the IL pretest associated with the

frequency of receiving prior library instruction?

Participants did

report having multiple ILI sessions during their undergraduate years at Rider

University. Whereas the majority (63%) of freshmen reported having no prior ILI

at Rider, by senior year nearly 80% had experienced one or multiple ILI

sessions. The finding of no correlation between the frequency of participants’

prior ILI and pretest scores suggests that students might not develop IL skills

through the “law of exposure” (Matthews, 2007). What they learn may not be

retained for or transferred to another research experience. Julien and Boon

(2004) reported a similar finding of students not retaining their IL learning

three or four months after the ILI. Numerous other studies also came to the

same conclusion that it is erroneous to assume that one or more ILI sessions in

the early college years will prepare students well for higher levels of

research work, and students do not become IL proficient from the single-session

ILI (Stec, 2006; Lechner, 2005; Johnson, 2011; Mokhtar & Majid, 2011; Wong

& Webb, 2011). It can be inferred from these findings that more intensified

IL training than the current single-session model needs to take place during

the four-year period for students to retain basic IL skills.

Do students improve their IL skills after the

ILI?

The pretest data

revealed that the IL level of all students was relatively low. The overall

differences between the pretests and posttests in the CMP-125 students were not

significant. This supports other findings that students’ learning from

single-session ILI is limited (Mokhtar & Majid, 2006; Portmann & Roush, 2004; Hsieh & Holden, 2010). While the credit

IL course is not the preferred or the primary way for IL training on most

college campuses (Tancheva et al., 2007), some librarians have embedded

themselves in the classroom over a period of time (Steiner & Madden, 2008),

or have actually gained grading power (Coulter , Clarke, & Scamman, 2007).

Moore Librarians need to investigate other means for working more closely with

the professors to integrate IL into their courses in the future in order to

increase the short- and long-term impact of ILI.

Reflections on constructing test items

Analysis of

responses to several individual test questions provided significant insight

regarding students' knowledge and misconceptions. More participants chose to

use “a web search engine for a complete list of references on the topic”

instead of “an encyclopedia” to find background information on an unfamiliar

topic (Q3). The answer for encyclopedia was revised in spring 2011 to include

online encyclopedias. As in the previous semester, the majority of participants

chose to use the Web over an encyclopedia. Many faculty members agreed with

students and considered a Web search engine a better tool than encyclopedias

for background information. Even though librarians prefer encyclopedia sources

for their reliability, it is hard for the library reference sources to compete

with the easy access of Web search engines. This preference of users, including

faculty members, for using the Web over traditional reference sources is an established

trend that was documented a decade ago in Rockman’s (2002) study. Considering

the development of the Web sources over the past decade, the Web could be

considered acceptable for this question on most topics, if not all.

Participants’ accuracy rates for the Boolean operators (AND/OR) in Q7

and Q9 were in 30% to 40% range. Biddix, Chung and Park (2011) observed that

library databases, with their subject, thesaurus and Boolean operators search

systems, are too complicated and problematic for students. Burkhardt (2007) was

dissatisfied with students’ improvement on Boolean operators over a

three-credit IL course. The authors of the current study agree with Kolowich

(2011) that the majority of students do not understand search logic and would

have great difficulty finding good sources. To master the basic search logic,

students need to learn the operators’ functions correctly and need practice to

reinforce their learning.

Few students reported they

would search for critiques of literary works by subject in the catalog as

indicated in Q6. Rider students were not exceptional when compared with those

in the study of Byerly et al., (2006) where only 1.6% of students chose the

correct answer for the question on subject search. Many more studies in the

literature also found students’ lack of knowledge on subject or controlled

vocabulary (Matthews, 2007; Brown & Krumholz, 2002; Lindsay et al., 2006;

Riddle & Hartman, 2000). In discussions with Rider faculty members about

the question, some of them disagreed with the importance that librarians tend

to place on subject searching; they preferred keyword searches instead. As

experienced researchers in their fields, these faculty members may know how to

use the appropriate keywords to find relevant items with considerable

efficiency. They are also motivated to spend the time to sort through large

numbers of returns for their studies. But the same knowledge and search mode

cannot be expected of most freshmen and sophomores. Even though librarians

would like to teach students about the concept of subject and controlled

vocabulary, various factors, including ingrained personal preferences and

habitual research patterns may make learning this concept a challenge.

Few participants had prior

knowledge about the use of truncation (Q8, Figure 7). Students in other

institutions also had trouble with this concept (Matthews, 2007; Furno &

Flanagan, 2008). Even though participants improved significantly in the

posttest, it remains the case that a minority (30%) scored correctly on the

question after the ILI.

More participants

chose journals than books as their source even when books may have been more

appropriate (Q10). Other researchers also noticed that college students are

overlooking the value of books and printed materials (Rockman, 2002; Head, 2012)

and do not understand the limitations of scholarly journals (Furno &

Flanagan, 2008; Schroeder & Mashek, 2007; Stec, 2006).

The finding that

students were weak in constructing search queries prompted the Moore librarians

to spend more time explaining the search concepts in the sessions. Vocabulary

may play a part in students’ understanding. Defining terms such as “truncation”

or avoiding library jargon may improve students’ search skills. Video clips and

tutorials were included in the class research guides to help students learn and

review the search logic and processes. Knowing that those students who had

prior ILI sessions might not remember or transfer that knowledge in more

advanced classes, some librarians used the inquiry method to determine what

these upper class students might already know about IL. If a majority of

students could answer the questions correctly, then the librarians would skip

teaching those concepts. The assessment findings also helped librarians work

more closely with the class faculty to include IL concepts in their

assignments.

Limitations

Moore librarians,

in teaching the course integrated one-session ILI, face serious limitations and

obstacles that the teaching faculty does not. Professors in a variety of

disciplines request ILI and have different requirements for their assignments.

Further, even though the librarians were aware of the common IL objectives for

students as well as the items on the tests, they necessarily taught to the

assignments, not to the tests. Some IL concepts received greater emphasis than

others during the ILI sessions. This lack of uniformity and control by

librarians in teaching IL is common for the single-session ILI in most

colleges. It would help if, in the future, librarians record which IL concepts

they teach in each session. This will allow for more precision in assessment by

relating what is taught to what students learn in the sessions.

Owing to the

limited class time in the session, the test instruments were very brief and

used only multiple-choice questions. The number of questions was not large

enough to provide a comprehensive picture of students’ IL skills.

Multiple-choice questions are limited when it comes to assessing participants’

higher order thinking skills (Oakleaf, 2008).

Nevertheless, the format is still widely used by researchers and educators because

access, data gathering, tabulation, and analysis are comparatively easy (Hsieh

& Holden, 2010). As suggested by Suskie (2007) and Oakleaf (2010), there is

no single instrument that can provide a comprehensive picture of IL competency.

When practicable, it is best to use multiple instruments– at least enough to

supplement the perspective gained from a single assessment tool. These could

include students’ reflections on their learning, one-minute papers and

librarians’ reviewing of students’ papers to evaluate students’ application of

research concepts and methods in actual productions. In addition, performance

measures, such as timing how long it takes students to complete searches, may

be useful, even though this method would be highly sensitive to individual

differences and learning styles.

The tests used in

the current research were developed over the course of two years. The

participants taking each test were the students in the ILI sessions of each

semester. There is a certain limitation in making comparisons among the

different cohorts because each cohort may have experiences that are different

from the other cohorts (Furno & Flanagan, 2008). Nevertheless, the tests on

the same concepts over the semesters captured accumulated snapshots of data that

revealed the strengths and weaknesses of not only the specific cohorts at

specific moments in time, but also over the longer-term, in this case two

years.

The librarians

found it challenging to develop perfect questions. Even though the librarians

encouraged students to use reference resources that are considered more

reliable than the freely available but, qualitatively, highly inconsistent

sources on the Web (Q3), and they would also like students to learn about

subject searching in the catalog because it is an efficient search method (Q6),

these questions could arguably have more than one correct answer depending on

user preferences and topics. The minor revision in the test questions in spring

2011 may have also affected test results albeit the impact seemed

insignificant. The authors continue to improve the assessment instrument,

including developing questions with multiple correct answers and the

opportunity to select multiple responses for each question. These changes will

reduce the impact of guessing and increase the psychometric quality of the

items. The librarians also intend to develop alternate versions of the test so

different pretests and posttests can be employed. This will reduce the effect

of memory for prior responses on performance and provide a better estimate of

learning.

Conclusions

Despite the

described limitations, the brief tests yielded meaningful information about the

students’ IL abilities for the Moore librarians, allowing for adjustment of IL

instruction and future assessment.

Among the findings, the IL program reached over 70% of the undergraduates

beyond their freshmen year. Students’ IL levels on the first two IL objectives

were relatively low, but significantly higher for IL Objective 1 than for IL

Objective 2. This means their skills

in identifying needed resources (ACRL IL Standards 1) were higher than those

related to information access (ACRL IL Standards 2). More importantly,

students’ basic IL levels correlate positively with their academic levels (e.g.

the Honors group), but not with their class years (e.g. freshman, sophomore) or

with the number of prior IL instruction they received. The pretests and

posttests of the Research Writing classes revealed that students’ gains over

one-session ILI were limited. Participants did improve significantly after the instruction on two IL concepts:

truncation and subject searching in the catalog.

The finding that

students did not improve their IL skills significantly via single-session ILI

is not new to the literature. On the other hand, the literature contains very

few investigations into students’ longer term learning outcomes in IL. This

study shows participants not demonstrating progress in IL despite possibly

multiple prior ILI over a span of years. This finding suggests that students in

all class years (including graduate students) need continued reinforcement of

basic IL concepts and skills.

The findings raise

the important question as to what can be done to help students learn and retain

IL more effectively in college. More – and multiple – teaching strategies,

including a combination of online, face-to-face, embedded librarian, credit

course, and curriculum mapping may be considered in the library’s future

instruction program as resources are made available. The librarians have also

considered other curricular changes such as providing students and/or teaching

faculty with answer sheets with rationales for each response for continual

learning. In addition, the Moore librarians planned with professors in

experimenting different pedagogies to reinforce student learning of IL in the

following semester. One had classes preview IL research guides and take a

graded quiz before ILI, another included interactive learning activities during

the ILI, and the other had multiple ILI and follow-up sessions. Comparisons of

these approaches will help determine which teaching methods might be the most

effective means for helping students improve their IL skills.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish

to thank the instruction librarians at the Franklin Moore Library of Rider University

for their support and dedication in administering the assessment instruments to

students in the information literacy instruction sessions in the past few

years. These colleagues include Diane Campbell, Robert Congleton, Melissa

Hofmann, Katharine Holden, Robert Lackie, Marilyn Quinn and Sharon Yang. We

also wish to express our appreciation to the Moore Library Assessment Committee

for the ideas its members offered during the design phase of this research

project and for its support throughout, and to colleagues Kathy Holden for

proofreading and to Hugh Holden for polishing the manuscript.

References

Angelo, T. A.,

& Cross, K. P. (1993). Classroom assessment techniques: A handbook for

college teachers. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

American Library

Association. Association of College and Research Libraries. (2000). Information

literacy competency standards for higher education. Retrieved

26 July 2013 from http://www.ala.org/ala/mgrps/divs/acrl/standards/informationliteracycompetency.cfm

BHP basic facts.

(n.d.). Information for prospective

and current students. In Rider

University. Retrieved 26 July 2013, from http://www.rider.edu/academics/academic-programs/honors-programs/baccalaureate-honors-program/bhp-basic-facts

Biddix, J. P., Chung, C. J., & Park, H. W. (2011). Convenience or

credibility: A study of college student online research behaviors. The Internet

and Higher Education, 14(3), 175-182. doi: 10.1016/j.iheduc.2011.01.003

Brown, C., &

Kingsley-Wilson, B. (2010). Assessing organically: turning an assignment into

an assessment. Reference Services Review, 38(4), 536-556. doi:10.1108/00907321011090719

Brown, C., &

Krumholz, L. R. (2002). Integrating information literacy into the science

curriculum. College & Research Libraries, 63(2), 111-123. Retrieved

26 July 2013 from https://abbynet.sd34.bc.ca/~dereck_dirom/035EEE2E-002F4E0D.9/Science.pdf

Burkhardt, J. M.

(2007). Assessing library skills: A first step to information literacy. Portal:

Libraries and the Academy, 7(1), 25-49. Retrieved 26 July 2013 from http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/portal_libraries_and_the_academy/v007/7.1burkhardt.html

Byerly, G.,

Downey, A., & Ramin, L. (2006). Footholds and foundations: Setting freshmen

on the path to lifelong learning. Reference Services Review, 34(4),

589-598. doi: 10.1108/00907320610716477

Campbell, D. K.

(2011). Broad focus, narrow focus: A look at information literacy across a

school of business and within a capstone course. Journal of Business &

Finance Librarianship, 16(4), 307-325. Retrieved 26 July 2013 from http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/08963568.2011.605622

Choinski, E.,

& Emanuel, M. (2006). The one-minute paper and the one-hour class: Outcomes

assessment for one-shot library instruction. Reference Services Review,

34(1), 148-155. doi: 10.1108/00907320610648824

Coulter, P.,

Clarke, S., & Scamman, C. (2007). Course grade as a measure of the

effectiveness of one-shot information literacy instruction. Public Services Quarterly,

3(1), 147-163. doi:10.1300/J295v03n01-08

Cunningham, A.

(2006). Using "ready-to-go" assessment tools to create a year long

assessment portfolio and improve instruction. College & Undergraduate Libraries, 13(2), 75-90.

doi:10.1300/J106v13n02_06

Dawson, P. H.,

& Campbell, D. K. (2009). Driving fast to nowhere on the information

highway: A look at a shifting paradigm of literacy in the twenty-first century.

In V. B. Cvetkovic & R. J. Lackie (Eds.), Teaching generation M: A handbook for librarians and educators (pp.

33-50). New York City, NY: Neal-Schuman.

Emmett, A., &

Emde, J. (2007). Assessing information literacy skills using the ACRL standards

as a guide. Reference Services Review, 35(2),

210-229. doi:10.1108/00907320710749146

Fain, M. (2011).

Assessing information literacy skills development in first year students: A

multi-year study. The Journal of Academic

Librarianship, 37(2), 109-119. doi: 10.1016/j.acalib.2011.02.002

Freeman, E., &

Lynd-Balta, E. (2010). Developing information literacy skills early in an

undergraduate curriculum. College

Teaching, 58(3), 109-115. Retrieved 26 July 2013 from ERIC database.

(EJ893019).

Furno, C., & Flanagan, D. (2008), “Information literacy: Getting the most

from your 60 minutes”, Reference Services Review, 36(3), 264-270. doi: 10.1108/00907320810895350

Gandhi, S. (2004).

Faculty-librarian collaboration to assess the effectiveness of a five-session

library instruction model. Community

& Junior College Libraries, 12(4), 15-48. doi:10.1300/J107v12n04_05

Goebel, N., Neff,

P., & Mandeville, A. (2007). Assessment within the Augustana model of

undergraduate discipline-specific information literacy credit courses. Public Services Quarterly, 3(1-2),

165-189.

Head, A. J.

(2012), “Learning curve: How college graduates solve information problems once

they join the workplace”. Project

Information Literacy Research Report. Retrieved 26 July 2013 from http://projectinfolit.org/pdfs/PIL_fall2012_workplaceStudy_FullReport.pdf

Heimke, J., &

Matthies, B. S. (2004). Assessing freshmen library skills and attitudes before

program development: One library’s experience. College & Undergraduate Libraries, 11(2), 29-49. doi: 10.1300/J106v11n02_03

Hsieh, M. L.,

& Dawson, P. H. (2010). A university’s information literacy assessment

program using Google Docs. Brick and Click Libraries: Proceedings of an

Academic Library Symposium, 119-128.

Hsieh, M. L., & Holden, H. A. (2010). The effectiveness of a

university’s single-session information literacy instruction. Reference Services Review, 38(3),

458-473. doi: 10.1108/00907321011070937

Hufford, J. R.

(2010). What are they learning? Pre- and post-assessment surveys for LIBR 1100,

introduction to library research. College

& Research Libraries, 71(2), 139-158. Retrieved 26 July 2013 from http://crl.acrl.org/content/71/2/139.full.pdf

Johnson, C. M.,

Anelli, C. M., Galbraith, B. J., & Green, K. A. (2011). Information

literacy instruction and assessment in an honors college science fundamentals

course. College & Research Libraries,

72(6), 533-547. Retrieved 26 July 2013 from http://crl.acrl.org/content/72/6/533.full.pdf+html

Johnson, W. G.

(2009). Developing an information literacy action plan. Community & Junior College Libraries, 15(4), 212-216.

doi:10.1080/02763910903269853

Julien, H., &

Boon, S. (2004). Assessing instructional outcomes in Canadian academic

libraries. Library & Information

Science Research, 26(2), 121-139. doi:10.1016/j.lisr.2004.01.008

Katz, I. R. (2007). Testing information literacy in digital

environments: ETS's iSkills assessment. Information

Technology & Libraries, 26(3), 3-12. doi: 10.6017/ital.v26i3.3271

Katz, I. R., & Macklin, A. S. (2007). Information and

communication technology (ICT) literacy: Integration and assessment in higher

education. Journal of Systemics,

Cybernetics and Informatics, 5(4), 50-55. Retrieved 26 July 2013 from http://www.iiisci.org/Journal/CV$/sci/pdfs/P890541.pdf

Knight, L. A.

(2002). The role of assessment in library user education. Reference Services Review, 30(1), 15-24. doi:

10.1108/00907320210416500

Kolowich, S.

(2011, August 22). What students don't

know [Web log post], Inside Higher Ed News. Retrieved 26 July 2013 from: http://www.insidehighered.com/news/2011/08/22/erial_study_of_student_research_habits_at_illinois_university_libraries_reveals_alarmingly_poor_information_literacy_and_skills

Lechner, D. L.

(2005). Graduate student research instruction: Testing an interactive web-based

library tutorial for a health sciences database. Research Strategies, 20(4), 469-481. doi: 10.1016/j.resstr.2006.12.017

Lindsay, E. B.,

Cummings, L., Johnson, C. M., & Scales, B. J. (2006). If you build it, will

they learn? Assessing online information literacy tutorials. College & Research Libraries, 67(5),

429-445. Retrieved 26 July 2013 from http://crl.acrl.org/content/67/5/429.full.pdf+html

Matthews, J. R.

(2007). Evaluation and measurement of

library services. Westport, CT: Libraries Unlimited.

McCulley, C.

(2009). Mixing and matching: Assessing information literacy. Communication in Information Literacy, 3(2),

171-180.

McDermott, D.

(2005). Library instruction for high-risk freshmen: Evaluating an enrichment

program. Reference Services Review, 33(4),

418-437. doi:10.1108/00907320510631553

Mery, Y., Newby,

J., & Peng, K. (2011). Assessing the reliability and validity of locally

developed information literacy test items. Reference

Services Review, 39(1), 98-122. doi:10.1108/00907321111108141

Merz, L. H., &

Mark, B. L. (2002). CLIP Note 32:

Assessment in college library instruction programs. Chicago, IL:

Association of College and Research Libraries.

Mokhtar, I. A., & Majid, S. (2006). Teaching information literacy

for in-depth knowledge and sustained learning. Education for Information, 24(1),

31-49.

Oakleaf, M. (2008). Dangers and opportunities: A conceptual map of

information literacy assessment approaches. Portal:

Libraries and the Academy, 8(3), 233-253. doi:10.1353/pla.0.0011

Oakleaf, M. (2010). The value of

academic libraries: A comprehensive research review and report. Association

of College and Research Libraries. Retrieved 26 July 2013 from http://www.ala.org/ala/mgrps/divs/acrl/issues/value/val_report.pdf

Oakleaf, M. (2011). Are they learning? Are we? Learning outcomes and the

academic library. Library Quarterly, 81(1),

61-82.

Portmann, C.A. & Roush, A.J. (2004), “Assessing

the effects of library instruction”, The

Journal of Academic Librarianship, 30(6),

461-465. doi: 10.1016/j.acalib.2004.07.004

Radcliff, C.,

Jensen, M. L., Salem, J. A., Burhanna, K. J., & Gedeon, J. A. (2007). A practical guide to information literacy

assessment for academic librarians. Westport, CT: Libraries Unlimited.

Radcliff, C. J.,

Salem, J. A., O'Connor, L. G., Burhanna, K. J. & Gedeon, J. A. (2007). Project SAILS skill sets for the 2011-2012

academic year [Description of Standardized Assessment of Information

Literacy Skills (SAILS) test]. Kent State University. Retrieved 26 July 2013,

from https://www.projectsails.org/SkillSets

Riddle, J. S., & Hartman, K. A. (2000). But are they learning

anything? Designing and assessment of first year library instruction. College & Undergraduate Libraries, 7(2),

59-69. doi: 10.1300/J106v07n02_06

Rockman, I. F.

(2002). Strengthening connections between information literacy, general

education, and assessment efforts. Library

Trends, 51(2), 185-198.

Rogers, R. R. (2001). Reflection in higher education: A concept

analysis. Innovative Higher Education, 26(1),

37-57. doi:10.1023/A:1010986404527

Rumble, J., &

Noe, N. (2009). Project SAILS: Launching information literacy assessment across

university waters. Technical Services

Quarterly, 26(4), 287-298. doi:10.1080/07317130802678936

Schroeder, R.,

& Mashek, K. B. (2007). Building a case for the teaching library: Using a

culture of assessment to reassure converted campus partners while persuading

the reluctant. Public Services Quarterly,

3(1-2), 83-110.

Silvernail, D. L.,

Small, D., Walker, L., Wilson, R. L., & Wintle, S. E. (2008). Using technology in helping students achieve

21st century skills: A pilot study. Center for Education

Policy, Applied Research, and Evaluation.

Staley, S. M., Branch, N. A., & Hewitt, T. L. (2010, September). Standardized

library instruction assessment: An institution-specific approach. Information Research: An International

Electronic Journal, 15(3), 1-22. Retrieved 29 July 2013 from http://www.eric.ed.gov/PDFS/EJ912761.pdf

Stec, E. M.

(2006). Using best practices: Librarians, graduate students and instruction. Reference Services Review, 34(1),

97-116. doi:10.1108/00907320610648798

Steiner, S. K.,

& Madden, M. L. (Eds.). (2008). The

desk and beyond: Next generation reference services. Chicago, IL: Association

of College and Research Libraries.

Suskie, L. (2007).

Answering the complex question of “how good is good enough?” Assessment Update, 19(4), 1-2, 12-13.

doi:10.1002/au.194

Tancheva, K.,

Andrews, C., & Steinhart, G. (2007). Library instruction assessment in

academic libraries. Public Services

Quarterly, 3(1-2), 29-56. doi:10.1300/J295v03n01_03

Tronstad, B.,

Phillips, L., Garcia, J., & Harlow, M. A. (2009). Assessing the TIP online

information literacy tutorial. Reference

Services Review, 37(1), 54-64. doi:10.1108/00907320910934995

Wong, S. H. R.,

& Webb, T. D. (2011). Uncovering meaningful correlation between student

academic performance and library material usage. College & Research Libraries, 72(4), 361-370. Retrieved 29 July

2013 from http://crl.acrl.org/content/72/4/361.abstract

Appendix A

Test Questions for IL Objective 1 (Questions

1 - 5) [Correct answers are italicized]

1. Typically a

library's online catalog contains:

a. Information

about books, videos, and other nonprint items in the library

b. The complete text of the

journal articles in the library

c. Information about the

college's courses

d. Full-text books

e. Don’t know

2. Which of the

following would be the best tool to use to obtain journal articles for your

topic “autistic children”?

a. The library’s online catalog

b. A library’s

database/index

c. An encyclopedia

d. Google

e. Don’t know

* Answer b changed to “A

database such as Academic Search Premier” in spring 2011.

3. You have gotten an assignment on “watersheds”

which you know very little about. What's the first thing you should do to get

started?

a. Browse the library shelves for books on watersheds.

b. Type “watersheds” in a web search engine for a complete list of

references on the topic.

c. Ask your friends if any of them know about your topic.

d. Find out some

basics on watersheds from an encyclopedia.

e. Ask the professor if you can change topics.

* Changed the question to:

You have gotten an assignment on “watersheds” about which you know very

little. What's the best way to get an overview of this topic?

* Answer d changed to “Find

out some basics on watersheds from an encyclopedia (online or print)” in spring

2011.

4. Which of the following are characteristics of

scholarly journals?

a. Contain colorful, glossy pages and typically accept commercial

advertising.

b. Mainly for the general public to read.

c. Report news events in a timely manner.

d. Articles

include detailed references.

e. Don’t know.

5. What is the easiest way to find out if the

library has the 1998 issues of Journal of Communication?

a. Search the library’s periodical shelves.

b. Search “Journal

Holdings” on the library Web page.

c. Search Google Scholar.

d. Search NoodleBib.

e. Don’t know.

* Question changed to “What

is the best way to find out if the Rider University Libraries have the full

text articles of the ….”

Appendix B

Test Questions for IL Objective 2 (Questions

6 - 10) [Correct answers are italicized]

To find the

critiques on William Shakespeare’s play Romeo and Juliet, in the Online

Catalog, I would do a search:

a. By title

b. By keyword

c. By subject

d. By author

e. Don’t know

* Question changed to “What is an efficient way to find critiques on

William Shakespeare’s …” in S6.

7. Which is the correct search strategy to

combine terms with the operators (AND, OR)?

a. Death penalty or capital punishment and women

b. Death penalty or (capital punishment and women)

c. (Death penalty

or capital punishment) and women

d. (Death penalty and women) or capital punishment”

e. I don't know

* Question changed to

“Which search statement is correct when you search for information on the topic

‘Should women be exempt from death penalty?’” in spring2011.

8. Truncation is a library

computer-searching term meaning that the last letter or letters of a word are

substituted with a symbol, such as “*” or “$”. A good reason you might truncate

a search term such as child* is that truncation will

a. limit the search to descriptor or subject fields

b. reduce the number of irrelevant citations

c. yield more

citations

d. save time in typing a long word

e. I don't know

![]() 2013 Hsieh, Dawson, and Carlin. This is an

Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 2.5 Canada (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.5/ca/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

2013 Hsieh, Dawson, and Carlin. This is an

Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 2.5 Canada (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.5/ca/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.