Article

Alignment of Citation Behaviors of Philosophy Graduate

Students and Faculty

Jennifer Knievel

Associate Professor / Director, Arts & Humanities

University of Colorado Boulder Libraries

Boulder, Colorado, United States of America

jennifer.knievel@colorado.edu

Received: 27 Mar. 2013 Accepted: 14

June 2013

2013 Knievel. This is an Open Access article

distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 2.5 Canada (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.5/ca/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

2013 Knievel. This is an Open Access article

distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 2.5 Canada (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.5/ca/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

Abstract

Objective – This study analyzes sources cited by graduate

students in philosophy at the University of Colorado Boulder (UCB) in 55 PhD

dissertations and master’s theses submitted between 2005 and 2010, to discover

their language, age, format, discipline, whether or not they were held by the

library, and how they were acquired. Results were compared to data previously

collected about sources cited by philosophy faculty at UCB, in books published

between 2004 and 2009, to identify how closely citation behaviors aligned

between the two groups.

Methods

– Citations

were counted in the PhD dissertations and master’s theses. Citations to

monographs were searched against the local catalog to determine ownership and

call number. Comparison numbers for faculty research were collected from a

previous study. Results were grouped

according to academic rank and analyzed by format, language, age, call number,

ownership, and method of purchase.

Results

– Graduate

students cited mostly books, though fewer than commonly found in other studies.

Citations were almost entirely of English language sources. Master’s students

cited slightly newer materials than doctoral students, who in turn cited newer

materials than faculty. The library owned most cited books, and most of those

were purchased on an approval plan. Doctoral students most frequently cited

resources outside the discipline of philosophy, in contrast to master’s

students and faculty.

Conclusions

–

The citation behavior of graduate students in

philosophy largely, but not entirely, mirrors that of the faculty. Further

study of citation behavior in humanities disciplines would be useful.

Understanding the behavior of philosophers can help philosophy librarians make

informed choices about how to spend library funds.

Introduction

Librarians

have long had an interest in better understanding how scholars use library

resources. Improved understanding of resource use can help librarians make more

efficient and effective use of limited acquisitions budgets. This understanding

can be somewhat elusive, and has been approached in many different ways. This

particular study attempts to take a user-perspective model of looking at

resource use employing a citation analysis. Rather than looking at an existing

library collection and asking how much it gets used, this study looks instead

at resources cited by graduate students at the University of Colorado at

Boulder (UCB), and whether or not the library owns them. A similar study of

faculty research at the same institution turned up some interesting findings,

and it became relevant to question whether or not graduate student research

behavior matched that of the faculty (Kellsey & Knievel, 2012). Most

citation analyses, for various reasons, focus primarily or exclusively on

science disciplines, but there is limited analysis in the literature of

humanities fields.

Objectives

This

study looks specifically at graduate theses and dissertations in the field of

philosophy to assess the extent to which the library collection holds the

materials cited by philosophy graduate students, as well as whether or not

philosophy graduate student research behaviors mirror those of philosophy

faculty.

The

author expected to find that graduate students in philosophy, as newer entrants

to the field, would use newer materials than the faculty. Since graduate

students request purchase of materials from their librarian less frequently

than faculty, the author expected more of the owned titles to be purchased on

approval rather than firm orders (this process is further explained below). The

author expected a high percentage of the cited materials to be classed within

the discipline of philosophy, rather than interdisciplinary. Finally, the

author expected the breakdown of the percentage of monographs and journals

cited, as well as the amount of non-English material used, to roughly match

those of the faculty.

Since

most citation analyses are of scientific fields, this study can help inform

collection development decisions in humanities fields, including whether or not

to target older materials and foreign languages for weeding, whether to focus

on disciplinary content and monographs for collection of new materials, and

whether or not approval plans for collection building effectively match

materials used by scholars.

Literature Review

A

robust conversation already exists in the literature about the strengths and

weaknesses of citation analysis (see, for example, Burright, Hahn, &

Antonisse, 2005; Hellqvist, 2010; MacRoberts & MacRoberts, 2010; McCain

& Bobick, 1981; Waugh & Ruppel, 2004; Smith, 2003; Sylvia, 1998;

Vallmitjana & Sabate, 2008; Zipp, 1996). Beile, Boote, and Killingsworth

(2004), among others, make persuasive arguments against using citation analysis

to develop core title lists for monographs or journals, or as a method of

measuring research quality. This study, however, makes use of citation analysis

for a different purpose for which the method is more effective, by employing

citations as a measurement of the resources local scholars needed, and whether

or not the library owns those sources.

Existing

literature in citation analysis (e.g., Iivonen, Nygren, Valtari, &

Heikkila, 2009), focuses heavily on journal citations and on the sciences. Few

analyze the humanities, and even fewer specifically analyze philosophy. John

East and John Cullars investigate philosophy specifically. Cullars (1998) found

15% of citations in philosophy materials were to foreign language resources. He

also found that a large majority of citations (85%) were to books, and that a

quarter of the cited sources were classed outside the area of philosophy. He

concluded that older materials were likely to be considered “recent” in

philosophy, including consistent use of materials up to nearly 40 years old.

Bandyopahyay (1999) also found that philosophy authors cited mostly books, but

studies by Kellsey and Knievel, (2012; 2005) found that philosophy scholars

tended to cite far more journals than other humanists, and that most citations

were to English language materials (Kellsey & Knievel, 2004). A study by

East (2003) also found almost no citations to non-English books in a year’s

worth of citations in two philosophy journals from 2002. A recent study of

graduate students included philosophy (Kayongo & Helm, 2012), and also

found that the philosophy students cited newer books and more journals than

other humanists.

Various

authors discuss the importance of evaluating the work of graduate students as a

measurement of the usefulness of a library collection (Edwards, 1999;

Kushkowski, Parsons, & Wiese, 2003; Washington-Hoagland & Clougherty,

2002). Thomas (2000) emphasizes the value of looking at local use and local

scholars. Zipp (1996) and McCain & Bobick (1981) both found that graduate

student resource use mirrors faculty usage. Both studies, however, focus on

science disciplines, and measure similarity of research based on lists of cited

journals. Neither study intended to evaluate whether graduate student research

mirrors faculty research in the humanities, nor did they look at language, format,

or interdisciplinarity of citations. Some studies have found that graduate

students tend to cite newer materials than faculty (Kushkowski et al., 2003;

Larivière, Sugimoto, & Bergeron, 2013; Zainab & Goi, 1997).

Some

studies call for more research into humanities sources (Sherriff, 2010; Smyth,

2011), since data collected and presented in these fields can help to influence

collection development policy in libraries. A few interdisciplinary citation

studies included some humanities (most notably Broadus, 1989; Buchanan &

Herubel, 1994; Kayongo & Helm, 2012; Leiding, 2005; Smith, 2003; Wiberley

& Jones, 1994; Wiberley & Jones, 2000; Wiberley, 2003). In general,

these studies found that humanists tended to cite more, and older, monographs

than scientists and social scientists. Smith (2003) found that ownership of

monographs was going down over time in the humanities. Wiberley (2002; 2003)

found that most humanists tended to cite materials within their own discipline,

though he did not evaluate philosophy in his studies.

This

study attempts to address the question of similarity of graduate student

behavior to that of faculty in a humanities discipline. It also attempts to

investigate an apparent contradiction of existing studies regarding the

dominance of monographs, as well as the use of foreign languages, in the

research of philosophy scholars. The results of this study can inform the

collection development choices of humanities librarians.

Method

This

study used a citation analysis approach. The author analyzed all of the

dissertations and theses submitted for the Department of Philosophy at the

University of Colorado Boulder (UCB) between 2005 and 2010. In that time

period, there were 26 doctoral dissertations and 29 master’s theses, for a

total of 55 source works. The results were compared with 9 faculty books

published between 2004 and 2009 by philosophy faculty at the same institution.

Most

citation analyses are conducted using tools such as Web of Science. However, in

the case of humanities disciplines like philosophy, which are comparatively

poorly covered in such tools, most citation analyses have to be hand-counted.

As is true of such citation analyses, it was necessary to make several choices

about how to categorize citations for the purposes of the study. These

decisions were made based on the study goals and characteristics of the

resources.

For

this study, the author followed the same process used in a 2012 study by

Kellsey and Knievel that analyzed citations in books published by philosophy faculty

at UCB during roughly the same time frame, in order to provide comparative

results. The 2012 study also provided comparison data for faculty behaviors.

Each citation was evaluated to determine if it cited a book or a journal, and

whether or not the work cited was in English or not in English. Works in

translation were counted in the language into which they were translated; thus,

a citation to an English translation of a French philosophical text was tallied

as English, since that was the language of the material actually used. Chapters

or articles in compiled volumes were counted as books, and counted in the

language of the cited chapter or article, not the language of the volume. Books

with multiple citations in one bibliography (to multiple chapters, for example)

were counted only once, since that measures availability, the focus of this

study, rather than intensity of use. Proceedings were counted as books or

journals depending upon how they were published; most were published as books.

Newspaper articles and encyclopedia entries were counted as articles. As with

the study this method emulates, law cases, dissertations, archival materials,

unpublished proceedings, and other unpublished works were not counted, since

unpublished materials did not provide useful analysis of overlap with the

locally held collection. The University of Colorado

Boulder (UCB) is a United States regional and federal depository, as well as a

United Nations depository, which means that the library automatically receives

copies of all documents published by government agencies. Hence it can be

generally assumed that UCB owns all government documents except in unusual

cases of missing or lost materials. Thus determining whether or not the library

owned cited government documents did not provide the enlightenment this study

sought, and government documents were not counted.

Many

libraries work with book vendors to set up profiles of materials that the

library automatically purchases. These arrangements are called approval plans, and

have become commonly used in large libraries throughout the United States. This

study attempted to determine whether the cited materials were purchased this

way, or if they were purchased through firm orders, meaning that a librarian

specifically requested a title that was not delivered via the approval plan.

Firm orders might be the result of specific requests by library patrons, or may

simply be the result of librarians noticing a title missing from the approval

plan that might be useful.

Once

each qualifying citation was identified, the books were checked against the

local library catalog to determine: 1. if the book is owned by the library, 2.

the call number (UCB uses Library of Congress classification for call numbers),

3. the publication date, and 4. whether it was ordered directly or via

approval. In philosophy, as with many other humanities disciplines, different

editions or translations are considered different works by scholars in the

field. Thus, only the exact edition cited was considered a match; if the

library owned the same title in a different edition it was not marked as a

title owned. Many records, especially for titles older than about 15 years, did

not indicate the method of purchase, so it could not be determined if the items

were purchased directly or via an approval plan.

Results

The

total number of citations counted was 3,910 in 55 dissertations and theses from

UCB, 3,000 of which were in the 26 PhD dissertations, with the remaining 910 in

the 29 master’s theses. The resulting data were grouped by graduate level to

facilitate more meaningful interpretation, and were analyzed in comparison with

each other, in the aggregate, and to faculty research. The faculty data for

comparison were drawn from 9 faculty books from the same department, which held

a total of 2,560 citations.

The

average of 71 citations per dissertation is slightly higher than the 59

citations per dissertation found by Zainab and Goi (1997). Average citations

per document diverged widely when looked at by student level, with 115

citations per PhD dissertation when dissertations are considered alone, and

only 31 citations per master’s thesis when looked at alone. Both are

considerably lower than the average of 284 citations per book by philosophy

faculty in the previous study.

Language

and Format

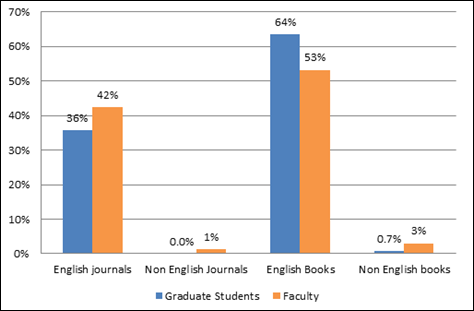

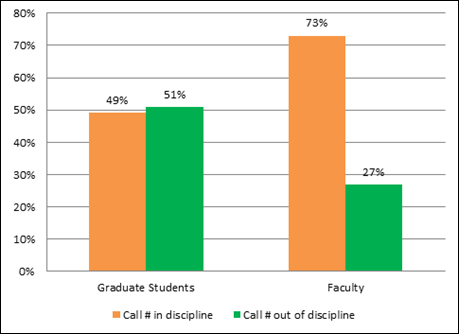

Among

dissertations and theses, 36% of the citations were of journal articles, while

42% percent of the citations in faculty books were of journal articles (see

Figure 1). An independent samples t-test revealed a statistically significant

difference between these groups. Citations in faculty books were more likely to

cite journal articles than those in dissertations and theses (t(8.7)=-5.0,

p=.001). Foreign language citations made up 0.7% of the total citations in the

theses and dissertations, and 4.3% of the total citations in faculty books. There

was no statistically significant difference between the two groups in the

amount of foreign language they cited.

Ownership

The

UCB library owned 83% of the books cited by graduate students, compared to the

81% of books cited by faculty (see Table 1). Though these numbers are very

close, there is a statistically significant difference in ownership of

materials cited by graduates and faculty (t(62)=-5.5,

p<.01).

Figure

1

Language

and format of cited works

Table

1

Ownership

of Cited Works

|

Type

|

Owned

|

Not Owned

|

|

Graduate Students

|

83%

|

17%

|

|

Faculty

|

81%

|

19%

|

Purchase

Method

Information

about how materials were purchased was not collected by the existing system

until 1995. As a result, only materials purchased after that time, regardless

of their publication date, included information about whether they were

purchased on an approval plan or as firm orders. Of the materials cited by

graduate students and owned by the library, 43% (897) included purchase

information. Of the materials for which purchase information was available, 82%

were purchased on approval (see Table 2). Of the materials cited by faculty and

owned by the library, a higher percentage, 84%, were ordered on approval. Like

the results of the owned/not owned data, though these figures are close to

those of the previous study of faculty sources in philosophy, there is a

statistical significance to the higher number of cited materials that were

acquired via firm order for the graduate students (t(62)=-2.8, p=.01).

Table

2

Purchase

Method of Cited Works

|

Type

|

Approval

|

Firm Order

|

|

Graduate Students

|

82%

|

18%

|

|

Faculty

|

84%

|

16%

|

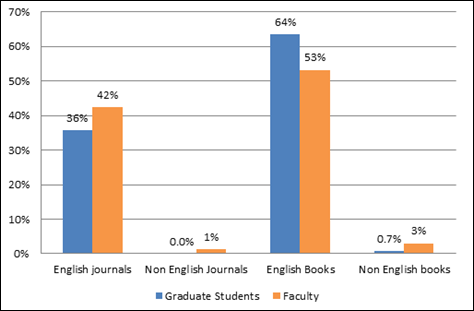

Age

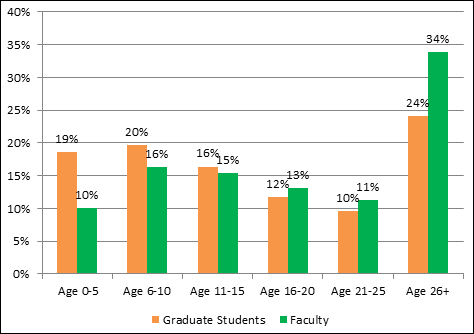

The

age distribution of citations in theses alone shows highest usage of very new

materials (5 years old or less), with a steady decline as materials age (see

Figure 2). Even materials older than 26 years, when grouped together as a

whole, proved fewer than the newest materials in master’s theses.

This

distribution of age of citations is in contrast with the PhD dissertations, in

which the largest age group of materials cited is the 26+ year range. Looking

at 5 year increments up to 25, the largest age group for PhD dissertations is

the 6-10 year range. Additionally, the dissertations cited a higher percentage

of materials in all of the older ranges as well, showing a general adoption and

use of older materials in dissertations than in theses (see Table 3).

Faculty

research follows this same pattern, using materials even older than those used

for the dissertations (see Figure 3). Faculty publications show a much more

pronounced jump in the 26+ age range, but are similar to the PhD dissertations

in that the largest 5 year span is the 6-10 year range (see Table 4).

Consistent

with that observation is the difference in average publication date of cited

materials, which was newer for theses than for dissertations, which in turn

were newer than faculty materials (see Table 5).

Interdisciplinarity

In

order to assess the interdisciplinarity of cited sources in the philosophy

theses and dissertations, the Library of Congress call numbers were recorded

for each cited book owned by the library, and then counted in groups. Anything

in the Library of Congress Classification System (LCCS) “B,” which includes

philosophy and religion, was considered “in discipline.” Everything else was

considered “out of discipline.”

Figure

2

Age

of works cited by graduate students

Table

3

Statistical

Tests: Age of Works Cited by Graduate Students

|

Age of Materials

|

Master’s Theses

|

PhD Dissertations

|

t-value

|

p-value

|

|

0-5 years

|

26%

|

17%

|

t(39)=-3

|

p<.01

|

|

6-10 years

|

20%

|

20%

|

t(32.3)=-5

|

p<.01

|

|

11-15 years

|

15%

|

17%

|

t(30.7)=-4.8

|

p<.01

|

|

16-20 years

|

10%

|

12%

|

t(32.3)=-4.6

|

p<.01

|

|

21-25 years

|

8%

|

10%

|

t(29.8)=-5

|

p<.01

|

|

26+ years

|

21%

|

25%

|

t(26.6)=-3.4

|

p<.01

|

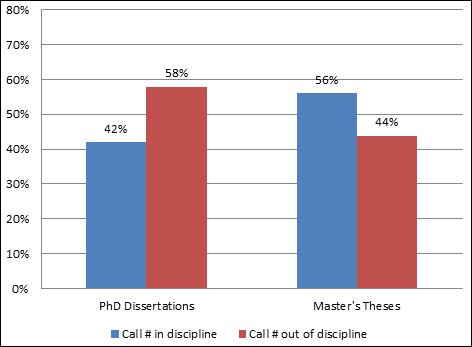

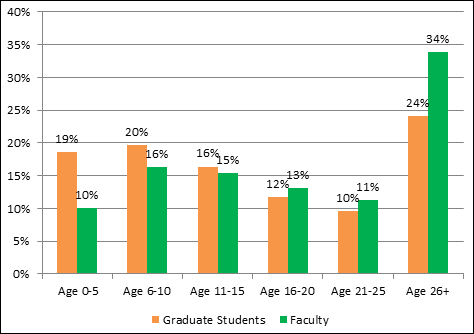

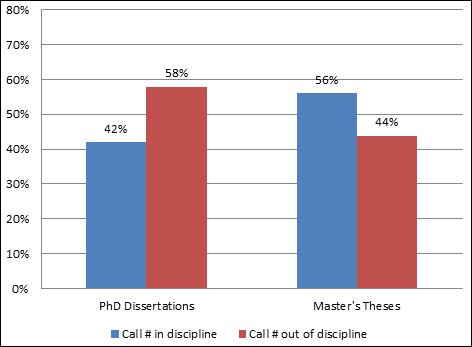

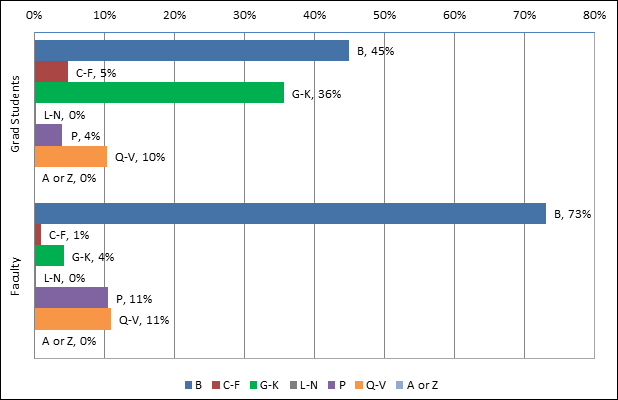

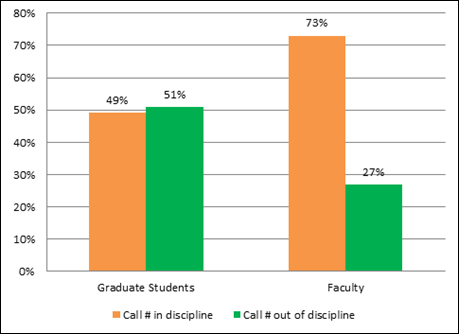

Of

the owned books cited in the PhD dissertations alone, a minority, only 42%,

classified as in discipline while 58% classified as out of discipline. In the

master’s theses, that breakdown was reversed, with 56% of citations in

discipline (see Figure 4). PhD dissertation writers were more likely to cite

materials published outside of the discipline than master’s thesis writers

(t(33.8)=-4, p<.01).

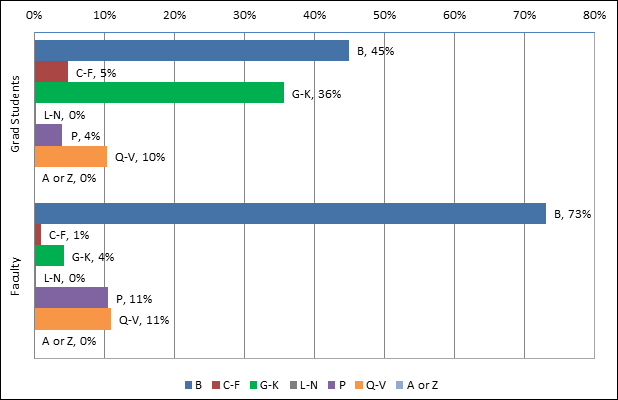

A

more detailed breakdown of the call numbers of cited works shows that the

majority of out of discipline citations for both theses and dissertations is in

the social science range (LCCS areas G-K). After social science, the next

largest discipline cited was science (Q-V), though only a third as many

citations were in this area. Even so, science alone represented more than

literature (P) and history (C-F) combined, with arts and education (L-N) and

reference (A and Z) almost completely absent (see Figure 5).

This

particular finding was dissimilar from research done with faculty citations,

which found a significantly higher percentage of faculty citations within the

discipline (see Figure 6; t(8.5)=-4, p<.01).

Discussion

Language

and Format

Of

the few existing analyses of citations in humanities dissertations and theses,

most ask whether scholars cited more books or journals. Most other studies

found a higher percentage of citations to monographs. However, inconsistent

counting methods make these numbers difficult to compare, since some other

studies counted duplicate citations more than once, or included government

documents as books, while this study did not. In this study, though citations

to monographs represent a majority among both groups, this percentage is

considerably lower than is typically seen in other humanities studies or in

older studies of philosophy (Cullars, 1998). This

higher percentage of citations to journals is consistent with more recent

studies of philosophy, and may reflect a transition of the discipline toward

being a more journal-reliant field than it once was (Kellsey

& Knievel, 2012; 2005). This may have an

influence on how philosophy librarians distribute their funding for materials,

since it may be prudent to devote more attention to serials in order to match

available resources with resource use.

Figure

3

Age

of works cited

Table

4

Statistical

Tests: Age of Works Cited by Graduate students and Faculty

|

Age of

Materials

|

Graduate

Students

|

Faculty Books

|

t-value

|

p-value

|

|

0-5 years

|

19%

|

10%

|

t(62)=-2.1

|

p=.04

|

|

6-10 years

|

20%

|

16%

|

t(62)=-4.6

|

p<.01

|

|

11-15 years

|

16%

|

15%

|

t(62)=-4.9

|

p<.01

|

|

16-20 years

|

12%

|

13%

|

t(62)=-5.8

|

p<.01

|

|

21-25 years

|

10%

|

11%

|

t(8.6)=-3.5

|

p=.01

|

|

26+ years

|

24%

|

34%

|

t(8.6)=-3.4

|

p=.01

|

Table

5

Average

Publication Date of Cited Works

|

Type

|

Average Pub Date

|

|

Master’s Theses

|

1991

|

|

PhD Dissertations

|

1988

|

|

Faculty Books

|

1984

|

A

particularly unusual result of this study is the near absence of any foreign

language citations, which made up less than 1% of the total citations. This

number is much lower than some studies have shown (Cullars, 1998), and yet is

more consistent with some other recent studies that have shown low usage of

foreign language materials by philosophy scholars (East, 2003; Kellsey &

Knievel, 2012; Kellsey & Knievel, 2004). The philosophy degree at UCB has

only a provisional language requirement, in which language study is required on

a case-by-case basis, if the student’s topic of interest necessitates it. This,

combined with the availability of translated material for study, may have an influence

on the very low usage of non-English material. In addition, there is a local

emphasis on applied ethics, which is a niche of philosophy that tends to eschew

continental philosophical approaches where foreign language might play a larger

role (Cullars, 1998).

Figure

4

Interdisciplinarity

of works cited by graduate students

Figure

5

Cited

discipline by call number classification

Figure

6

Interdisciplinarity of cited works

The

language and format distribution of the materials cited by graduate students

mirrors very closely those cited by faculty. This finding supports Zipp’s

(1996) analysis that graduate student research is reflective of faculty

research, but other significant factors discussed below need to be assessed to

determine whether graduate student citation behavior really does align with

faculty behavior in the humanities.

Ownership

Between

81 and 83% of cited monographs were owned locally. This number can be

interpreted in various ways; 83% is very high, and clearly the library is

collecting a large majority of the sources used by students. At the same time,

this is an indication that nearly 1 in every 5 sources are being obtained by

the students or faculty through interlibrary loan (ILL) or some other

mechanism, which, from the user perspective, may feel like a burden. The

not-owned material may be partly explained by the number of sources cited from

outside the field of philosophy, which will be further addressed below. Another

explanation may be a local practice of not purchasing volumes of collected

articles that have been previously published elsewhere; students may not be

finding the previously published versions that are in alternative locations,

and instead are acquiring the volumes of collected articles. It is worth

reiterating here that only exact editions were considered a match. Many of the

not-owned materials were held in different editions. These findings may

indicate a need to purchase more duplicative material, such as the collected

works, since there is reason to suspect that students and faculty are still

using the collected works but attaining them through borrowing or other means.

The ownership percentages are much higher than the un-weighted owned percentage

of 63% of cited humanities materials in a similar study by Kayongo & Helm

(2012). It is hard to establish a bench-mark of what percentage of cited

materials should be owned by the local library. As a result of budget

pressures, many libraries are moving away from the “just-in-case” philosophy of

collection development, which would logically drive down the percentage of

cited materials that are already owned.

Purchase

Method

Since

PhD dissertation topics tend to be narrow and relatively unexplored, it is

logical that the library approval plan would not necessarily reflect the newer

topics, so 82% seems like a reasonable percentage of titles to be ordered on

approval. The faculty are more established scholars, and tend to remain at the

institution for longer periods than the students. Thus it is easier to

establish approval profiles to provide a higher percentage of the materials of

interest to the faculty. Also, since more of the materials cited by faculty

fall into the philosophy classification (see below), it is easier for a subject

librarian to ensure coverage in the collection of topics of interest to the

philosophy scholars.

Age

Of

the three groups, master’s theses cited the newest materials, PhD dissertations

cited slightly older materials, and faculty books cited the oldest materials of

the three. This is consistent with other studies that have shown that graduate

students user newer sources than faculty, and may be a result of the fact that

graduate students, by their nature, are performing comprehensive literature

reviews for their projects, while faculty are building on a more mature

research agenda and may be less aggressive in identifying new related

literature. The results of this study are consistent with other humanities

studies in showing that humanists use older materials than scientists or social

scientists. Librarians should take into account these differences of field of

study before making choices about materials to target for weeding projects, or

assuming that humanities materials lose their value as a direct function of

their age, as may be more true in scientific disciplines.

Interdisciplinarity

Surprisingly,

faculty authors were the most strict adherents to their own disciplinary

material of all the groups studied. PhD dissertations demonstrated the weakest

tie to disciplinary material, as this was the only group for whom fewer than

half of the cited sources were classified in philosophy. In this way, graduate

students and faculty show more divergence in the materials they choose to cite

in their research. If this citation pattern were to continue as these graduate

students become members of philosophy faculties, this could have an influence

on how librarians want to define their collections. In order to address the

current need of graduate students, as well as the potential future needs of

faculty, librarians should also be reaching across traditional disciplinary

definitions to ensure that the library is collecting relevant materials in

disciplines related to philosophy. In this study, those relationships are in

areas not traditionally associated with philosophy: the social sciences and the

sciences, rather than the other humanities. Thus it may be useful for

philosophy librarians to build new understandings with other librarians to

ensure sufficient breadth of coverage in a library collection.

Conclusion

This

study took a user-perspective approach to analyzing resource use by philosophy

scholars. Building on the earlier study of faculty research behaviors, this

study analyzed citations in philosophy master’s theses and PhD dissertations

from the University of Colorado Boulder for their format (monograph or

journal), language (English or other), age, presence in the local library,

method of acquisition (approval or firm order), and subject classification.

This

study found that in most ways except interdisciplinarity, graduate student

research mirrored faculty research. In contrast to some earlier studies, this

study found almost no use of foreign language sources by philosophy scholars.

Generally, the percentage of cited sources owned by the library was high, over

three-quarters, and of the sources with purchasing information, more than three

quarters had been purchased on approval plans. The majority of citations were

to monographs, with PhD dissertations citing roughly two thirds monographs, and

master’s theses slightly less. Master’s theses cited somewhat newer materials than

PhD dissertations, which in turn cited newer materials than faculty

publications analyzed in a previous study. The most notable separation between

faculty and graduate student research behaviors was that graduate student

research cited a much higher percentage of materials classed outside of

philosophy than faculty research did.

Further

similar studies of both faculty and graduate students in other humanities

disciplines would be of interest to assess whether the results found in this

study reflect an average result or an outlier.

Results

of this study can help to develop the picture of how humanities scholars use

library resources. It can be useful for humanities librarians as they evaluate

their collection development policies and practices related to journals,

foreign language, and approval plans, as well as provide some data to help

determine policies and practices related to age and language for weeding of

materials.

References

Bandyopadhyay, A. K.

(1999). Literature use pattern in doctoral dissertations of different

disciplines. International Information

Communication and Education, 18(1),

33-42.

Beile, P. M., Boote, D.

N., & Killingsworth, E. K. (2004). A microscope or a mirror?: A question of

study validity regarding the use of dissertation citation analysis for

evaluating research collections. Journal

of Academic Librarianship, 30(5),

347-353.

Broadus, R. N. (1989).

Use of periodicals by humanities scholars. Serials

Librarian, 16(1), 123-131. doi:

10.1300/J12v1601_10

Buchanan, A. L., &

Herubel, J.P. V. M. (1994). Profiling PhD dissertation bibliographies: Serials

and collection development in political science. Behavioral and Social Sciences Librarian, 13(1), 1-10. doi: 10.1300/J103v13n01_01

Burright, M. A., Hahn,

T. B., & Antonisse, M. J. (2005). Understanding information use in a

multidisciplinary field: A local citation analysis of neuroscience research. College & Research Libraries, 66(3), 198-210.

Cullars, J. M. (1998).

Citation characteristics of English-language monographs in philosophy. Library & Information Science Research,

20(1), 41-68.

East, J. W. (2003).

Australian library resources in philosophy: A survey of recent monograph

holdings. Australian Academic and

Research Libraries, 34(2), 92-99.

Edwards, S. (1999).

Citation analysis as a collection development tool: A bibliometric study of

polymer science theses and dissertations. Serials

Review, 25(1), 11-20.

Hellqvist, B. (2010).

Referencing in the humanities and its implications for citation analysis. Journal of the American Society for

Information Science and Technology, 61(2),

310-318.

Iivonen, M.,

Nygren, U., Valtari, A., & Heikkila, T. (2009). Library collections

contribute to doctoral studies: Citation analysis of dissertations in the field

of economics and administration. Library

Management, 30(3), 185-203.

Kayongo, J., &

Helm, C. (2012). Relevance of library collections for graduate student

research: A citation analysis study of doctoral dissertations at Notre Dame. College & Research Libraries, 73(1), 47-67.

Kellsey, C., &

Knievel, J. (2012). Overlap between humanities faculty citation and library

monograph collections 2004–2009. College

& Research Libraries, 73(6),

569-583.

Kellsey, C., &

Knievel, J. E. (2004). Global English in the humanities? A longitudinal

citation study of foreign-language use by humanities scholars. College & Research Libraries, 65(3), 194-204.

Knievel, J. E., &

Kellsey, C. (2005). Citation analysis for collection development: A comparative

study of eight humanities fields. Library

Quarterly, 75(2), 142-168. doi:

10.1086/431331

Kushkowski, J. D.,

Parsons, K. A., & Wiese, W. H. (2003). Master's and doctoral thesis

citations: Analysis and trends of a longitudinal study. Portal: Libraries and the Academy, 3(3), 459-479.

Larivière, V.,

Sugimoto, C. R., & Bergeron, P. (2013). In their own image? A comparison of

doctoral students' and faculty members' referencing behavior. Journal of the American Society for

Information Science and Technology, 64(5),

1045-1054. doi:10.1002/asi.22797

Leiding, R. (2005). Using

citation checking of undergraduate honors thesis bibliographies to evaluate

library collections. College &

Research Libraries, 66(5),

417-429.

MacRoberts, M. H.,

& MacRoberts, B. R. (2010). Problems of citation analysis: A study of

uncited and seldom-cited influences. Journal

of the American Society for Information Science & Technology, 61(1), 1-12. doi:10.1002/asi.21228

McCain, K. W., &

Bobick, J. E. (1981). Patterns of journal use in a departmental library: A

citation analysis. Journal of the

American Society for Information Science, 32(4), 257-267. doi: 10.1002/asi.4630320405

Sherriff, G. (2010).

Information use in history research: A citation analysis of master's level

theses. Portal: Libraries and the Academy,

10(2), 165-183. doi:

10.1353/pla.0.0092

Smith, E. T. (2003).

Assessing collection usefulness: An investigation of library ownership of the

resources graduate students use. College

& Research Libraries, 64(5),

344-355.

Smyth, J. B. (2011).

Tracking trends: Students' information use in the social sciences and

humanities, 1995-2008. Portal: Libraries and the Academy, 11(1),

551–573. doi: 10.1353/pla.2011.0009

Sylvia, M. J. (1998).

Citation analysis as an unobtrusive method for journal collection evaluation

using psychology student research bibliographies. Collection Building, 17(1),

20-28.

Thomas, J. (2000).

Never enough: Graduate student use of journals-- citation analysis of social

work theses. Behavioral & Social Sciences Librarian, 19(1), 1-16. doi: 10.1300/J103v19n01_01

Vallmitjana, N.,

& Sabate, L. G. (2008). Citation analysis of Ph.D.

dissertation references as a tool for collection management in an academic

chemistry library. College & Research

Libraries, 69(1), 72-81.

Washington-Hoagland,

C., & Clougherty, L. (2002). Identifying the

resource and service needs of graduate and professional students: The

University of Iowa user needs of graduate professional series. Portal: Libraries & the Academy, 2(1), 125-143. doi: 10.1353/pla.2002.0014

Waugh, C. K. &

Ruppel, M. (2004). Citation analysis of dissertation, thesis, and research paper

references in workforce education and development. Journal of Academic Librarianship, 30(4), 276-284.

Wiberley, S., &

Jones, W. G. (1994). Humanists revisited: A longitudinal look at the adoption

of information technology. College and

Research Libraries, 55(6),

499-509.

Wiberley, S., &

Jones, W. G. (2000). Time and technology: A decade-long look at humanists' use

of electronic information technology. College

and Research Libraries, 61(5), 421-431.

Wiberley, S. E. (2002).

The humanities: Who won the '90s in scholarly book publishing. Portal: Libraries and the Academy, 2(3),

357-374.

Wiberley, S. E. (2003).

A methodological approach to developing bibliometric models of types of

humanities scholarship. Library

Quarterly, 73(2), 121-159.

Zainab, A. N., & Goi, S.

S. (1997). Characteristics of citations used by humanities researchers. Malaysian Journal of Library and Information

Science, 2(2), 19-36.

Zipp, L. S. (1996).

Thesis and dissertation citations as indicators of faculty research use of

university library journal collections. Library

Resources & Technical Services, 40(4), 335-342. doi:

10.5860/lrts.40n4.335

![]() 2013 Knievel. This is an Open Access article

distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 2.5 Canada (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.5/ca/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

2013 Knievel. This is an Open Access article

distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 2.5 Canada (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.5/ca/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.