Conference Paper

Coding Practices for LibQUAL+® Open-Ended

Comments

Karen Neurohr

Assessment Librarian

Oklahoma State University

Stillwater, Oklahoma,

United States of America

Email: karen.neurohr@okstate.edu

Eric Ackermann

Head, Reference Services and Library Assessment

Radford University

Radford, Virginia, United States of America

Email: egackerma@radford.edu

Daniel P. O'Mahony

Director of Library Planning and Assessment

Brown University Library

Providence, Rhode Island, United States of America

Email: dpo@brown.edu

Lynda S. White

Associate Director of Library Assessment

University of Virginia Library

Charlottesville, Virginia, United States of America

Email: lsw6y@virginia.edu

2013 Neurohr, Ackermann, O’Mahony,

and White.

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative

Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 2.5 Canada (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.5/ca/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

2013 Neurohr, Ackermann, O’Mahony,

and White.

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative

Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 2.5 Canada (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.5/ca/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

Abstract

Objective – This paper presents the results of a study of

libraries’ practices for coding open-ended comments collected through LibQUAL+® surveys and suggests practical steps for

facilitating this qualitative analysis.

Methods

– In the fall of 2009, survey invitations were sent

to contacts at 641 institutions that had participated in the LibQUAL+® survey from 2003 to 2009. Of those invited, there

were 154 respondents, for an overall response rate of 24.0%.

Results

– Nearly 87% of the respondents indicated that their

library had performed a qualitative analysis of the comments from their most

recent LibQUAL+® survey. Of these, over 65% used

computer software to organize, code, sort, or analyze their comments, while

33.6% hand-coded their comments on paper. Of the 76 respondents who provided

information on software, 73.7% used Excel, 18.4% used Atlas.ti,

and 7.9% used NVivo. Most institutions (55.8%) had

only 1 person coding the comments; 26.9% had 2 coders, and very few had 3 or

more. Of those who performed some type of analysis on their comments, nearly

all (91.9%) indicated that they developed keywords and topics from reading

through the comments (emergent keywords). Another common approach was to code

the comments according to the LibQUAL+® dimensions;

55.0% of respondents used this strategy. Nearly all of the institutions (92.7%)

reported using their LibQUAL+® comments internally to

improve library operations. Libraries also typically incorporated the comments

into local university reports (75.5%) and used the comments in outreach

communications to the university community (60.9%).

Conclusion

–

Comments obtained from the LibQUAL+® survey can be

useful for strategic planning, understanding users, identifying areas for

improvement, and prioritizing needs. A key suggestion raised by respondents to

this survey was for practitioners to consider sharing the fruits of their labor

more widely, including coding taxonomies and strategies, as well as broader

discussion of qualitative analysis methods and practices.

Introduction

Since its launch in 2000, LibQUAL+®

has become the most prevalent library assessment instrument for measuring

service quality.

LibQUAL+® has been used to

collect service quality assessment perceptions from 1,294,674 participants at

1,164 institutions around the world. LibQUAL+® has

been implemented in 28 language variations: Afrikaans, Chinese, Danish, Dutch,

English (American, British, Dutch, Finnish, France, Norwegian, Swedish, Swiss),

Finnish, French (British English-BE, Belge, Canada,

France, Swiss), German (and German Swiss), Greek, Hebrew, Japanese, Norwegian,

Spanish, Swedish (and Swedish BE), and Welsh (Kyrillidou,

Thompson, & Cook, 2011, p. 3).

A

key component of the LibQUAL+® survey data is the

file of respondents’ free-text comments that accompanies the quantitative data

– almost 40% of LibQUAL+® respondents

typically include narrative comments (Green & Kyrillidou,

2010, p. 26).

“[T]he open-ended comments gathered as part of LibQUAL+®

are themselves useful in fleshing out insights into

perceived library service quality. Respondents often use the

comments box on the survey to make constructive suggestions on specific ways to

address their concerns” (Cook et al., 2008, p. 14).

Thus,

systematic analysis of a library’s qualitative data from LibQUAL+®

can be extremely valuable in assessing the library’s performance and

identifying areas for improvement.

To

better understand libraries’ current practices in analyzing and using LibQUAL+® comments, the authors conducted a survey of all

U.S. and Canadian libraries that administered at least one LibQUAL+®

survey from 2003 through June 2009. Survey questions asked respondents to

describe what they did with the open-ended comments received from their LibQUAL+® survey and probed aspects including coding

methods, local resources for coding, and the use of comments for various

purposes. This paper presents the survey findings as well as suggestions for

practical steps to help facilitate qualitative analysis of LibQUAL+®

comments. The questionnaire can be found at http://www.library.okstate.edu/dean/neurohr/CodingSurvey10-26-09.pdf.

Literature Review/Bibliography

A search of the published, peer-reviewed

library literature found 12 articles and conference papers produced by 11

academic libraries: Bowling Green State University (Haricombe

& Boettcher, 2004); Northeastern University (Habich,

2009); Notre Dame (Jones & Kayongo, 2009); Texas

A&M (Guidry, 2002; Clark, 2007); University of Arizona (Begay,

Lee, Martin, & Ray, 2004); University of British Columbia (Friesen, 2009);

University of Idaho (Jankowska, Hertel,

& Young, 2006); University of

Massachusetts-Amherst (Fretwell, 2009); University of

Pittsburgh (Knapp, 2004); Vanderbilt University (Wilson, 2004); Western

Michigan University (Dennis & Bower, 2008). These articles covered LibQUAL+® surveys administered during the

period from 2001 to 2007 and for the most part described the methodologies,

experiences, and findings of individual libraries that performed some type of

systematic analysis of their survey’s comments.

All 1 institutions represented in the

literature review were doctorate-granting universities. Seven of these 11

libraries were members of ARL (Begay et al., 2004;

Guidry, 2002; Clark, 2007; Jones & Kayongo, 2009;

Fretwell, 2009; Friesen, 2009; Knapp, 2004; Wilson,

2004). Ten of the 11 institutions are located in the United States: 3 in the

Northeast, 3 in the South, 2 in the Midwest, and 2 in the West, while the

eleventh institution is located in Canada.

The amount of detail reported in the

literature review by libraries about the management of their coding projects

was relatively sparse and inconsistent. Only 3 of the 11 libraries represented

in the literature review reported any project structure, all of which were ad

hoc or informal (Begay et al., 2004; Habich, 2009; Jankowska et al.,

2006). Three of the libraries reported the number of coders they used: one

reported using one coder (Habich, 2009), and two

reported using two coders (Dennis & Bower, 2008; Jones & Kayongo, 2009). Two non-librarians were involved in the

coding (Dennis & Bower, 2008; Guidry, 2002). Only one of the libraries

reported providing formal training for their coders by way of a consultant (Begay et al., 2004) while another

library’s coder was self-taught (Habich, 2009). The

remaining nine libraries did not provide any information on coder training.

All 11 of these libraries reported performing

qualitative analysis on either all or a representative sample of the comments

they received from the LibQUAL+® surveys they

conducted, which was part of the criteria for selecting these 11 articles. The

average number of comments received by these 11 libraries was 1,031. Seven of

the 12 authors reported using computer software to help in the analysis (Begay et al., Dennis & Bower, 2008; Friesen, 2009;

Guidry, 2002; Habich, 2009; Haricombe

& Boettcher, 2004; Jones & Kayongo, 2009)

while 5 did not report what coding method (by computer or by hand) they used

(Clark, 2007; Fretwell, 2009; Jankowska

et al., 2006; Knapp, 2004; Wilson, 2004). Of the seven libraries that reported

using software, three used ATLAS.ti (Dennis &

Bower, 2008; Friesen, 2009; Guidry, 2002), two used Excel (Habich,

2009; Jones & Kayongo, 2009), one used NUD*IST – now

called NVivo – (Begay et

al., 2004), and one used Access (Haricombe &

Boettcher, 2004).

The 11 libraries covered in the literature

review varied in the way they developed a coding system for use in the analysis

of their LibQUAL+® comment data. Five of the 11

reported basing their codes on the 3 LibQUAL+®

dimensions Affect of Service, Information Control,

and Library as Place (Friesen, 2009; Habich, 2009; Jankowska et al., 2006; Jones & Kayongo,

2009; Wilson, 2004). Three of the 11 libraries also based their

coding on the individual LibQUAL+® and/or local

questions (Friesen, 2009; Habich, 2009; Jones & Kayongo, 2009). Three of the libraries reported

using a predetermined set of concepts or keywords (Begay

et al., 2004; Haricombe & Boettcher, 2004; Jones &

Kayongo, 2009), while nine reported using keywords

and concepts developed from the content of the comments (Begay

et al., 2004; Clark, 2007; Dennis & Bower, 2008; Fretwell,

2009; Friesen, 2009; Guidry, 2002; Habich, 2009; Haricombe & Boettcher, 2004; Jankowska

et al., 2006). Nine of the 11 libraries reported coding the distinct

topics found within each comment in lieu of using 1 code for the entire comment

(Begay et al., 2004; Dennis & Bower, 2008; Fretwell, 2009; Friesen, 2009; Guidry, 2002; Habich, 2009; Haricombe &

Boettcher, 2004; Jones & Kayongo, 2009; Wilson,

2004). Seven of the libraries also coded a comment “positive” or

“negative” if it expressed such an experience with an aspect of the library (Begay et al., 2004; Dennis & Bower, 2008; Fretwell, 2009; Friesen, 2009; Guidry, 2002; Habich, 2009; Wilson, 2004). Note that the use of each of

the elements discussed above was not exclusive. Each of these libraries

reported using a different combination in developing their coding system. Only

one did not include any report of the elements it used to create its coding

schema (Knapp, 2004).

Only 2 of the 11 libraries reported any

detailed information about the steps they took to encourage or enforce coding

consistency and reduce coding subjectivity during their projects. Both reported

that their coders worked using an understanding gained through prior discussion

of how to apply the codes (Begay et al., 2004; Jones

& Kayongo, 2009), but only one had their coders

work independently on randomly assigned sets of comments (Begay

et al., 2004). None of these libraries reported documenting their coding

procedures.

All 11 of the libraries also reported using

the results to communicate with other professionals in the field (Begay et al., 2004; Clark, 2007; Dennis & Bower, 2008; Fretwell, 2009; Friesen, 2009; Guidry, 2002; Habich, 2009; Haricombe &

Boettcher, 2004; Jankowska et al., 2006; Jones & Kayongo, 2009; Knapp, 2004; Wilson, 2004). Few of the 11

libraries reported any further plans to use the results of their qualitative

analysis. One library reported plans to incorporate some of their findings into

their annual reports and other intra-university administrative reports (Dennis

& Bower, 2008). Only three planned to include the findings in outreach

communications to their university (Dennis & Bower, 2008; Habich, 2009; Haricombe &

Boettcher, 2004) or to external groups (e.g., donors or potential donors; Habich, 2009).

The libraries represented in the literature

review reported several benefits from analyzing their comment data. Two of the

libraries gained a better understanding of library users’ needs and priorities

(Jones & Kayongo, 2009; Fretwell,

2009). One found a new source of ideas for new services (Begay,

2004). Three libraries found a new source for improving existing services

(Clark, 2007; Friesen, 2009; Wilson, 2004). One found a new source for

maximizing the impact of limited resources (Habich,

2009). Three of the 11 libraries reported that they had developed a new tool

for analyzing other data sets (Begay et al., 2004;

Dennis & Bower, 2008; Jankowska et al., 2006).

Two discovered that the findings from analyzing the LibQUAL+®

comment data complemented and enhanced the findings from the quantitative data

(Dennis & Bower, 2008; Jones & Kayongo,

2009).

Only one of these libraries indicated the

nature of the biggest challenge they encountered during the project, which was

devising a method for comment analysis that did not require learning a new

software program (Habich, 2009). None of the

libraries represented reported on what support from their institutions,

vendors, or others they wished they had during the project. Only one mentioned

a resource they found helpful: the survey research expertise available in their

university’s Office of Institutional Research (Habich,

2009).

Methodology

LibQUAL+®

quantitative measures have been thoroughly investigated and validated, but what

about the qualitative data? Each survey includes an open-ended statement:

“Please enter any comments about library services in the box below.” How do

libraries analyze and use the data received in response to this statement?

In

the fall of 2008, a small working group began to study this question. The study

was initially informed by feedback obtained by one of the authors new to LibQUAL+® who queried the LibQUAL-L discussion list in February 2008 by asking, “Can anyone share

information about how they coded the open-ended comments from the LibQUAL+® survey?” The wide variety in the

responses received led to the ad hoc formation of a luncheon affinity group to

discuss coding at the 2008 Library Assessment Conference in Seattle. Over 15

librarians participated in the affinity group and there was much interest in

coding methodologies and practices. Next, the authors met to discuss ways to

explore coding, drafted a survey and planned for the survey’s distribution.

In September 2009, the survey questionnaire

was piloted to a small group of 30 colleagues who

had responded to the listserv query or participated in the affinity group. They

assisted the authors in clarifying the wording and structure of the

questionnaire by answering these questions about the draft:

1.

How

long did it take to complete the survey? (The goal was 10 minutes or less.)

2.

Can

you answer the questions quickly/easily?

3.

Are the

questions clear? Which are not? Do you have suggestions for clarification?

4.

Are

the questions generic enough to cover most possible situations at your

institution or others you are familiar with?

5.

Other

comments.

The Association of Research Libraries (ARL)

provided generous assistance by emailing survey

invitations to all of the contacts at North American institutions that

participated in the LibQUAL+® survey from 2003

through spring 2009. There were 641 institutions: 110 ARL members (84 from the

United States and 16 from Canada) and 531 non-members (515 in the United States

and 28 in Canada). The first invitation was sent on October 27, 2009, followed

by four reminders at one-week intervals. Of those invited, there were 154

respondents for an overall response rate of 24.0%.

Survey Results

The survey asked what kind of institution the

respondent was affiliated with by using the Carnegie classifications for higher

education. Of the 151 responses to this question, 9.3% were from baccalaureate

colleges, 36.4% from master’s colleges and universities, and 54.3% were from

doctorate-granting universities (see Figure 1). There were no responses from

other types of institutions.

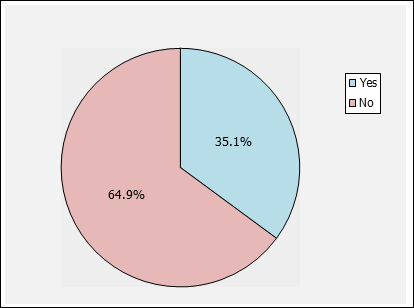

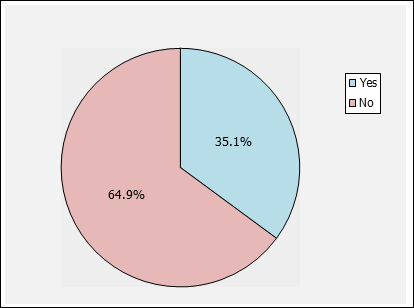

ARL members comprised 35.1% of the respondents to the survey (Figure 2).

ARL members were over-represented in the response, since only 17.2% of the 641

libraries in the sample were ARL members.

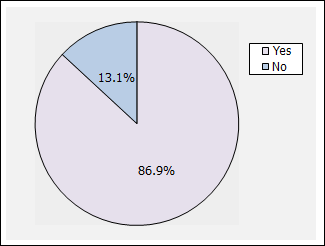

A large majority of the 154 respondents

(85.1%) were from the United States with the remaining libraries from Canada

(Figure 3). Nonetheless, Canadian libraries were over-represented in the

response, at 14.9%; only 9.4% of the 641 libraries in the sample were Canadian.

A little more than 33% of the U.S. respondents

were from the Northeast section of the country, closely followed by the South

and Midwest. Only 11.5% were from the Western states (Figure 4). For 60.2% of

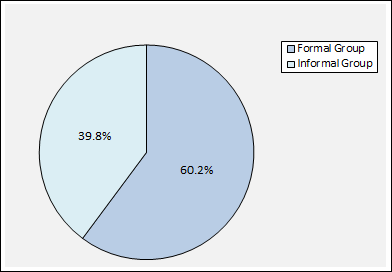

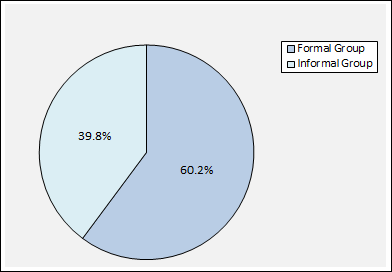

respondents, administration of the LibQUAL+® survey

was handled by a formal or standing group within the library. or by someone whose position included survey administration.

Thus, among these respondents, there appeared to be some permanent

responsibility in their library for assessment (Figure 5). Nearly 40%

implemented LibQUAL+® through an informal or ad hoc

team or project group.

Figure 1

What is your

institution type?

Figure 2

Does your library belong to the Association of

Research Libraries (ARL)?

Figure 3

Country

Figure 4

Sections of the United States

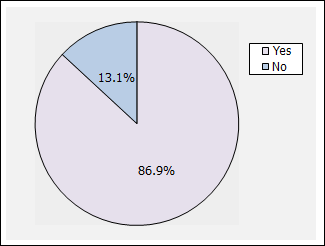

Nearly 87% of the respondents indicated that

their library had performed a qualitative analysis of the comments from their

most recent LibQUAL+® survey (Figure 6), where

“qualitative analysis” was described as any process that organized or

categorized or tagged/coded the free-text comments so that they might be used

by library staff or others in assessing and/or improving library services. Of those

who did not perform analysis on their survey comments, the most frequently

mentioned reason was lack of staff time. The average number of LibQUAL+® comments received by responding libraries was

379. The median was 293 but the number of comments ranged from one to 1,420.

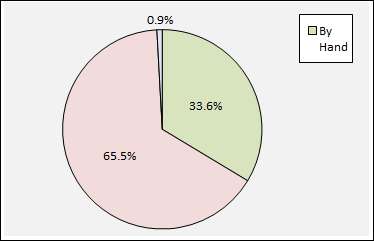

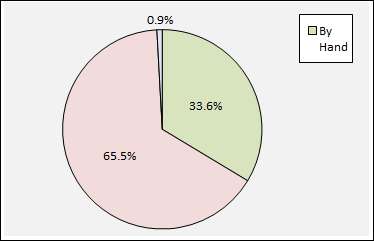

The survey asked those who had performed a

qualitative analysis of their comments about the tools and methods they used in

their approach. Of the 114 responding libraries that provided answers, over 65%

used some sort of computer software to organize, code, sort, or analyze their comments,

while 33.6% hand coded their comments on paper (Figure 7).

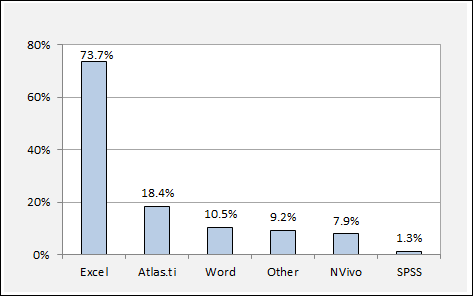

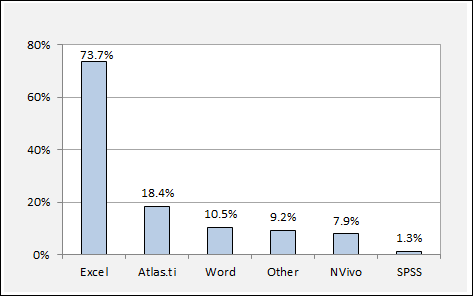

The survey revealed that coders primarily used

Excel to analyze the comments: of the 76 respondents that provided information

on software, 73.7% used Excel (Figure 8). ATLAS.ti

was the most common qualitative data analysis software used (18.4% for ATLAS.ti versus 7.9% for NVivo).

Figure 5

LibQUAL+® administrators

Figure 6

Did you perform

qualitative analysis of the open-ended comments?

Figure 7

Coding methods

Figure 8

Software used (respondents could choose more

than one option)

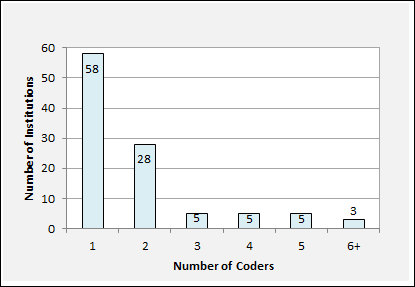

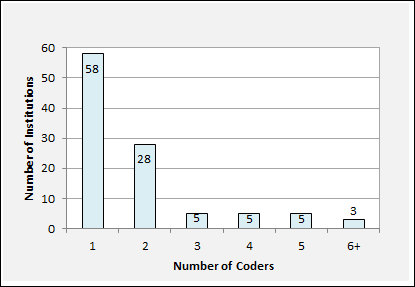

Most respondents (58 out of 104 libraries, or

55.8%) had only 1 person coding the comments (Figure 9). Twenty-eight (26.9%)

had 2 coders, but

very few had 3 or more. Thus, at over 80% of the

responding libraries, either 1 or 2 people performed the coding. Only 18

libraries (17.3%) had 3 or more people who did coding.

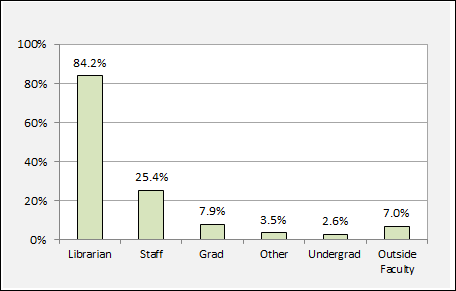

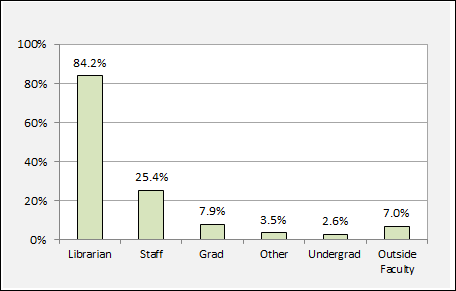

Staff who performed the coding at respondents’

libraries were typically professional librarians:

84.2% of respondents indicated that librarians were coders while 25.4% used

non-librarian staff (Figure 10).

Training for coders came from several venues,

primarily LibQUAL+® workshops run by ARL (69.6%), but

there was also a large contingent that was self-taught or who had taken formal

courses in assessment methods (Figure 11). “Other” tended to be consultants

from other areas of the local institution.

Respondents used a number of approaches to

code the comments (Table 1). Of those who performed some type of analysis on

their comments, nearly all (91.9%) indicated that they developed keywords and

topics from reading through the comments (emergent keywords). Another common

approach was to code the comments according to LibQUAL+®

dimensions (55.0% of respondents used this strategy). Less common was coding

according to the 22 individual LibQUAL+® questions

(done by only 27.0%). A couple of respondents specifically mentioned that

creating a word cloud to visually display the key concepts that emerged from

their LibQUAL+® comments was an effective tool,

especially in communicating their findings to others.

Figure 9

Number of institutions with n coders

Figure 10

Coder status (respondents could choose more

than one option)

Figure 11

Training activities (respondents could choose

more than one option)

Table 1

Basis For Coding the

Comments

|

Basis

for Coding the Comments:*

|

%

|

N

|

|

Emergent keywords or concepts (e.g.,

“service hours”) developed from reading the comments?

|

91.9%

|

102

|

|

Whether or not it expressed a “positive” or

“negative” perspective/experience of the library?

|

67.6%

|

75

|

|

The LibQUAL+® dimensions: Affect of Service, Information Control, & Library as

Place?

|

55.0%

|

61

|

|

The number of distinct topic(s) in a single

respondent’s comment?

|

46.8%

|

52

|

|

A pre-set list of keywords or concepts

(e.g., “service hours”)?

|

41.4%

|

46

|

|

The 22 individual LibQUAL+®

questions and/or the 5 local questions?

|

27.0%

|

30

|

|

Other

|

10.8%

|

12

|

In order to enhance consistency and

objectivity, a number of steps were often implemented, including training,

using previous coding schemes, and having others check the work of a single

coder (33% of “other”). See Table 2.

Roughly half (51.4%) of those responding to

the survey did not document the process they used to code/analyze their LibQUAL+® comments (Table 3). The most common documentation

produced was lists of tags/codes with definitions and descriptions of the procedure

or methodology used.

Nearly all (92.7%) of the responding libraries

reported using their LibQUAL+® comments internally to

improve library operations (Table 4). Libraries also typically incorporated the

comments into local university reports (75.5%) and used the comments in

outreach communications to the university community (60.9%). Notably, roughly

half (46.4%) of respondents said they either did or planned to include their LibQUAL+® comments in communications with professional

communities (e.g., in conference presentations or professional publications).

Benefits

The survey asked, “For your library, what was

the best benefit of coding the comments?” The two most frequently mentioned

benefits were (1) that the comments helped to identify action items for improvement,

and (2) that the comments helped the library better understand its users

(Figure 12). Other benefits included providing results and examples that can be

communicated to various library constituents such as the provost or potential

donors, identifying and analyzing specific needs and issues raised by users,

identifying trends and patterns, and corroborating the quantitative survey

data.

Table 2

Consistency in Coding

|

Consistency in coding was assured by:*

|

%

|

N

|

|

Training and/or discussion was conducted

ahead of time for all participants to ensure a common understanding of the

application of the codes/tags

|

44.6%

|

37

|

|

Coding schemes and definitions from previous

survey administrations were consulted

|

44.6%

|

37

|

|

Other (please specify)

|

43.4%

|

36

|

|

Each comment was coded independently by at

least two people

|

27.7%

|

23

|

|

Comments were randomly assigned to people

doing the coding

|

12.0%

|

10

|

*Respondents could choose more than one

option.

Table 3

Documentation Type

|

Documentation Type*

|

%

|

N

|

|

None; did not document the process

|

51.4%

|

55

|

|

Code book (list of tags/codes, definitions,

examples, etc)

|

27.1%

|

29

|

|

Description of procedure and methodology

|

25.2%

|

27

|

|

Other (please specify)

|

17.8%

|

19

|

*Respondents could choose more than one option.

Table 4

Uses of Comment Data

|

Uses of Comment Data*

|

Yes

|

No

|

Plan to do

|

|

Internally within the library for

operational improvements

|

92.7%

|

0.9%

|

6.4%

|

|

Incorporated into administrative reports to

the university community (e.g., in annual report, budget request, etc.)

|

75.5%

|

7.3%

|

16.4%

|

|

Included in outreach communications to the

university community (e.g., in announcements for new services)

|

60.9%

|

18.2%

|

17.3%

|

|

Included in communication with professional

community (e.g., in conference presentations or professional publication)

|

25.5%

|

43.6%

|

20.9%

|

|

Included in outreach communications to

external audiences such as donors or potential donors (e.g., demonstrate

satisfaction with funded gifts or express need for funds, etc.)

|

22.7%

|

38.2%

|

27.3%

|

|

Other

|

3.6%

|

20.9%

|

0.9%

|

*Respondents could choose more than one

option.

Challenges

When it came to the biggest challenges of

coding the comments, time constraints were mentioned most frequently (Figure

13). Time here referred not only to the duration of coding itself, but also

included the time it took to learn new software, and the time to manage

multiple coders. Closely related to lack of time was the expressed challenge of

lack of people/staff to perform the coding and analysis. Another

resource-related challenge was the lack of appropriate software.

Respondents also described a number of

challenges related to the process of performing the actual coding and analysis,

including developing categories/groupings for coding schemes. Other less

frequently mentioned challenges included dealing with multiple concepts,

maintaining consistency throughout the coding process, the difficulty in

maintaining objectivity, and the need for assistance in analyzing and

interpreting the data. Some respondents also commented on the sheer volume of

the qualitative data (the average number of comments per responding library was

379, with each comment likely to contain numerous concepts to be coded

separately).

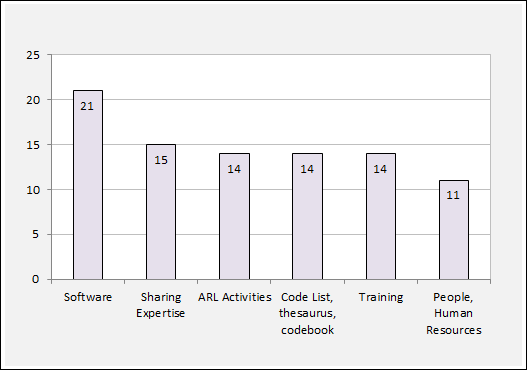

Support Needed

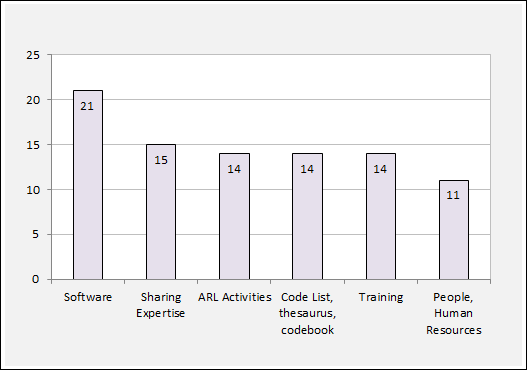

The survey asked, “What kind of support (from

your library, institution, ARL, software vendor, etc.) would be most helpful to

you in doing qualitative analysis of LibQUAL+®

comments?” Software purchase and software training were cited most frequently (Figure 14).

Respondents also made a number of suggestions regarding sharing information,

experiences, and work products in conducting the coding of LibQUAL+®

comments, as well as sharing the results of the qualitative analysis. For

example:

·

“Perhaps

the sharing of the index terms that others have used”

·

“It

might be interesting for a group … to draft a thesaurus and research

commonalities and trends across universities."

·

“It

would be great to share comments or types of comments, for informal

benchmarking, similar to how we can compare our scores on items through the

notebooks."

Figure 12

Best benefits of coding

Figure 13

Biggest challenges

of coding

ARL was gratefully acknowledged for their many

workshops and training/sharing sessions on LibQUAL+®

generally, but there was also an expressed interest in online training/webinars

on coding. In addition, a desire for basic training in qualitative research

theory/methodologies was mentioned, as well as training for the actual coding

and analysis. More staff to help with coding was desired by several

respondents.

Recommended Resources

Finally, the survey asked the respondents to

recommend helpful resources for someone new at starting a coding project. The

resource mentioned most often was ARL with its myriad activities which include

publications, the Library Service Quality Academy, the Library Assessment Conference

and proceedings, the LibQUAL+® website and workshops,

and the Assessment listserv/blog (Table 5). Other resources mentioned included

experts on campus, software vendors’ workshops and websites, and formal

research courses. The works of two institutions were mentioned specifically:

the Brown University guide (http://old.libqual.org/documents/admin/BrownU_2005_LQ_qual_method.pdf) and articles from Notre Dame (see, for

example, Jones & Kayongo, 2009).

Figure 14

Most helpful support

for coding

Table 5

Recommended Resources

Recommended resources:

|

N

|

|

ARL Activities

|

20

|

|

None or Unsure

|

12

|

|

Online Resources

|

9

|

|

Software Manuals, Training,

Tutorials, Websites

|

7

|

|

Articles, Books

|

6

|

|

Suggestions

|

5

|

|

Formal and Informal Coursework

|

4

|

|

Institutional, Campus Resources

|

3

|

|

Manuals, guides

|

3

|

Several specific resources were listed by

survey respondents as helpful starting points for conducting qualitative

research:

Corbin, J. & Strauss, A. (2008). Basics of qualitative research. Los Angeles, CA: Sage. (Or

another book on grounded theory generation)

Richards, L. (2005). Handling qualitative data: A practical guide. London: Sage Publications.

LaPelle, N. (2004). Simplifying qualitative data analysis

using general purpose software tools. Field Methods, 16(1),

85-108.

Online QDA. (2012). School of Human

& Health Sciences, University of Huddersfield. Retrieved 30 May 2013

from http://onlineqda.hud.ac.uk/Introduction/index.php

Šauperl, A. (n.d.). Qualitative research methods in information

and library science: an annotated bibliography of sources, In University of Ljubljana, Faculty of Arts,

Department of Library and Information Science and Book Studies.. Retrieved

30 May 2013 from http://uisk.ff.cuni.cz/dwn/1003/1725cs_CZ_Qualitative%20Research%20Methods-Bibliography.rtf

Conclusion

Comments obtained from the LibQUAL+®

survey can be useful for strategic planning, understanding users, identifying

areas for improvement, and prioritizing needs. Clearly, the survey results

indicated a strong interest in systematically analyzing the open-ended comments

from the LibQUAL+® survey: nearly 87% of respondents

performed qualitative analysis on their most recent LibQUAL+®

comments, and of that group more than 65% utilized a computer software tool in

conducting that analysis. In more than half of the responding libraries, LibQUAL+® analysis was conducted by individuals or groups

with permanent responsibility for assessment. However, nearly 33% of

respondents indicated they had no training and were self-taught regarding

qualitative analysis.

Overall, respondents expressed a strong desire

for assistance in learning how to code and for knowing the best practices used

by other libraries. Far and away, Microsoft Excel was the tool of choice as

nearly 75% of respondents used it for some aspect of their analysis. There

appeared to be some confusion about the capabilities of text analysis software

packages, presumably by those who had not used such a tool (e.g., several

respondents commented on not using any software that “automatically” assigned

codes to the text).

A key suggestion raised by respondents to this

survey was for practitioners to consider sharing the fruits of their labor more

widely (including coding taxonomies and coding strategies) as well as broader

discussion of qualitative analysis methods, strategies, approaches, and

practices. To this end, it was encouraging that more than half of the survey

respondents indicated that they either already had or planned to include their LibQUAL+® comments in communications with professional

communities (e.g., in conference presentations or professional publications).

Such sharing of information, methods, and results should be welcomed given that

the literature review performed as part of this study revealed very few items

that focused on performing a systematic analysis of LibQUAL+®

comments.

Administering a LibQUAL+® survey typically results in a wealth of data, and

librarians want to know how best to use it. Performing qualitative analysis of

the open-ended comments is a typical practice with multiple benefits

accompanied by multiple challenges. A variety of tools and methods are utilized

by libraries.

Acknowledgement

The authors gratefully acknowledge

the input of the librarians who responded to the ARL LibQUAL-L

query, participated in the Library Assessment Conference Affinity Group, tested

and provided input for the pilot survey, and took the “LibQUAL+®

Comment Coding Survey.” Also, the authors thank ARL for their work and

cooperation in sending the survey invitations. We hope that this exploratory

study helps describe the current state of practice of qualitative analysis

among LibQUAL+® libraries and provides a basis from

which the emerging community of interest might grow.

References

Begay, W., Lee, D. R., Martin, J., & Ray, M.

(2004). Quantifying qualitative data: Using LibQUAL+® comments for library-wide planning

activities at the University of Arizona. Journal

of Library Administration, 40(3/4), 111-119. doi:10.1300/J111v40n03_09.

Clark, D. (2007). Practical assessment at

Texas A&M Libraries: Using LibQUAL+®

comments to enhance reference services. In F. DeFranco,

S. Hiller, L. J. Hinchliffe, K. Justh,

M. Kyrillidou, J. Self, & J. Stein (Eds.), Proceedings of the Library Assessment

Conference: Building effective, sustainable, practical assessment, (pp.

91-94). Washington, DC: Association of Research Libraries. Retrieved 30 May

2013 from http://libraryassessment.org/bm~doc/proceedings-lac-2006.pdf

Cook, C., Heath, F., Thompson, B., Davis, M., Kyrillidou, M., & Roebuck, G. (2008). LibQUAL+® 2008 survey

results notebook– ARL.

Washington, DC: Association of Research Libraries. Retrieved 30 May 2013 from http://www.libqual.org/documents/admin/ARL_Notebook_2008.pdf

Dennis, B. W., & Bower, T. (2008). Using content analysis

software to analyze survey comments. portal: Libraries and the Academy 8(4), 423-437. doi:10.1353/pla.0.0015

Fretwell, G. (2009). Examining the overlooked: Open-ended

comments from 6,108 invalid 2007 LibQUAL+® survey

responses. In S. Hiller, K. Justh, M. Kyrillidou, & J. Self (Eds.), Proceedings of the Library Assessment Conference:Building effective, sustainable, practical assessment

(pp. 443-448). Washington, DC: Association of Research Libraries. Retrieved

30 May 2013 http://libraryassessment.org/bm~doc/proceedings-lac-2008.pdf

Friesen, M. (2009). Applying ATLAS.ti

and Nesstar WebView to the LibQUAL+® results at UBC Library: Getting started. In S.

Hiller, K. Justh, M. Kyrillidou,

& J. Self (Eds.), Proceedings of the

Library Assessment Conference: Building effective, sustainable, practical

assessment (pp. 449-455). Washington, DC: Association of Research

Libraries. Retrieved 30 May 2013 from http://libraryassessment.org/bm~doc/proceedings-lac-2008.pdf

Green, D., & Kyrillidou,

M. (2010). LibQUAL+® procedures manual, including

the LibQUAL+® Lite

feature. Washington, DC: Association of Research Libraries.

Guidry, J. A. (2002). LibQUAL+®

spring 2001 comments: A qualitative analysis using ATLAS.ti.

Performance Measurement and Metrics 3(2),

100-107. doi:10.1108/14678040210429008

Habich, E. C. (2009). Analyzing LibQUAL+® comments

using Excel: An accessible tool for engaging discussion and action. In S. Hiller, K. Justh,

M. Kyrillidou, & J. Self (Eds.), Proceedings of the Library Assessment

Conference: Building effective, sustainable,practical assessment (pp. 417-423).Washington,

DC: Association of Research Libraries. Retrieved 30 May 2013 from

http://libraryassessment.org/bm~doc/proceedings-lac-2008.pdf

Haricombe, L. J., & Boettcher, B. J. (2004). Using LibQUAL+® data

in strategic planning: Bowling Green State University. Journal of Library Administration, 40(3/4), 181-195. doi:10.1300/J111v40n03_14.

Jankowska, M. A., Hertel, K.,

& Young, N. J. (2006).

Improving library service quality to graduate students: LibQUAL+® survey results in a

practical setting. portal: Libraries and the Academy, 6(1), 59-77. doi:10.1353/pla.2006.0005

Jones, S., & Kayongo,

J. (2009). Are they really

that different?: Identifying needs and priorities

across user groups and disciplines at the University of Notre Dame through LibQUAL+® user comments. In S. Hiller, K. Justh, M. Kyrillidou, & J.

Self (Eds.), Proceedings of the Library

Assessment Conference: Building effective, sustainable, practical assessment (pp.

425-441). Washington, DC: Association of

Research Libraries.

Retrieved 20 May 2013 from http://libraryassessment.org/bm~doc/proceedings-lac-2008.pdf

Knapp, A. E. (2004). We asked them what they thought, now what do we

do? The use of LibQUAL+®

data to redesign public services at the University of Pittsburgh. Journal of Library Administration, 40(3/4),

157-171. doi:10.1300/J111v40n03_12

Kyrillidou, M., Thompson, B., & Cook, C. (2011,

Aug.). Regrounding LibQUAL+® for the Digital Library Environment: an analysis

of the DigiQUAL Data. Paper presented at the 9th

Northumbria International Conference on Performance Measurement in Libraries

and Information Services, York, England.

Wilson, F. (2004). LibQUAL+® 2002

at Vanderbilt University: What do the results mean and where do we go from

here? Journal of Library Administration,

40(3/4), 197-240. doi:

10.1300/J111v40n03_15.

![]() 2013 Neurohr, Ackermann, O’Mahony,

and White.

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative

Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 2.5 Canada (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.5/ca/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

2013 Neurohr, Ackermann, O’Mahony,

and White.

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative

Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 2.5 Canada (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.5/ca/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.