Article

Information Literacy Articles in Science Pedagogy

Journals

Cara Bradley

Teaching and Learning

Librarian

University of Regina

Regina, Saskatchewan, Canada

Email: cara.bradley@uregina.ca

Received: 24 July 2013 Accepted:

19 Nov. 2013

![]() 2013 Bradley. This is an Open Access article

distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 2.5 Canada (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.5/ca/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

2013 Bradley. This is an Open Access article

distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 2.5 Canada (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.5/ca/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

Abstract

Objective – This study sought to determine the extent

to which articles about information literacy-related topics have been published

in science pedagogy journals. It also explored the nature of these references,

in terms of authorship, Association of College and Research Libraries (ACRL)

information literacy competency standards addressed, and degree of emphasis on

information literacy topics. In addition to characterizing information literacy

in the science pedagogy literature, the study presents a methodology that can

be adopted by future efforts to explore representations of information literacy

in the literature of additional academic disciplines.

Methods – The 2011 Journal Citation Reports® Science edition was

used to identify the 15 journals with the highest impact factor in the

“Education—Scientific Disciplines” subject category. Initially Web of Science

was searched to identify occurrences of “information literacy” and related

terms in the journals of interest during the 10 year period 2002-2011. This was

supplemented by a title scan of the articles to ensure inclusion of relevant

items that did not include library-centric terminology. Abstracts and, where

necessary, full papers were reviewed to confirm relevance. Only articles were

included: editorials, news items, letters, and resource reviews were excluded

from the analysis.

Articles selected for inclusion were read in their entirety. Professional

designations for each author were identified to characterize the authorship of

this body of literature. Articles were also classified according to levels

developed by O’Connor (2008), to indicate whether information literacy was a

“Major Topic,” “Substantive Focus,” “Incidental Mention,” or “Not Explicitly

Named.” Further analysis mapped each article to the ACRL information literacy

competency standards (2000), to provide more detailed insight into which

standards are most frequently addressed in this body of literature.

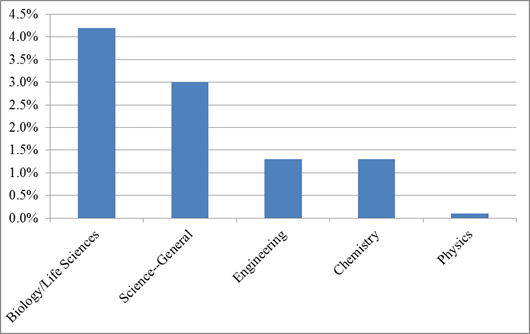

Results – Articles on information literacy-related topics appear only

sporadically in science pedagogy journals, and that frequency varies depending

on the specific subject area. Overall, librarians contribute a relatively small

proportion of these articles, and are more likely to co-author with teaching

faculty/graduate students than to publish alone or with other librarians. The

degree of focus on information literacy topics (O’Connor level) varies

depending on article authorship, with librarians more likely to treat

information literacy as the “Major Focus” of their work. Additionally, the articles

tend to cluster around ACRL information literacy standards two, three, and

especially four, rather than addressing them equally.

Conclusions – The presence of some articles on information

literacy-related topics in science pedagogy journals suggests that there is a

willingness among these journals to publish work in this area. Despite this,

relatively few librarians have pursued this publication option, choosing

instead to publish articles on information literacy topics within the library

and information studies (LIS) literature. As a result, librarians are missing

out on the opportunity to share their published work in venues more likely to

be seen and valued by subject faculty, and on the chance to familiarize science

educators with information literacy topics. Future research should focus on:

librarians’ rationale when selecting target publications for their information

literacy writing; science educator interest in writing and reading about

information literacy topics in their pedagogical journals; and the impact of

articles about information literacy in these journals on subject faculty

perceptions of the topic’s importance.

The methods used in this research have implications for the study of

information literacy in other academic disciplines, and demonstrate that the

study of information literacy in the literature of academic disciplines can

provide valuable insights into representations and characterizations of

information literacy in diverse fields of study. A better understanding of how

subject faculty think and write about information literacy in their scholarly

literature could have a significant impact on how librarians approach and

collaborate with faculty in all fields of study.

Introduction

Thousands of journal articles, books,

standards, and other documents have been written on the topic of information

literacy over the past two decades. Library and information studies (LIS)

venues have published the vast majority of this work, where it is read

primarily by librarians with a pre-existing interest in the topic. This body of

literature is certainly important, as it has promoted information literacy to a

wider LIS audience and helped to refine the profession’s understanding of the

concept.

Of particular interest to the current study,

however, is the degree to which information literacy has permeated the

pedagogical literature in the academic disciplines; that is, the literature

that is most likely to be read by teaching faculty. Research has repeatedly

demonstrated that curricular integration of information literacy competency

development is essential to its success, and such integration cannot happen

without the willing participation of faculty teaching in the disciplines (Kearns & Hybl,

2005; Lampert, 2005). This study approaches pedagogical literature in the disciplines as

one measure of the interest in and uptake of information literacy among

educators. In addition to quantifying information literacy’s presence in the

science pedagogical literature, it also attempts to characterize the nature of

this work. It is hoped that the results will provide guidance and insight to

librarians, whether they are considering publication venues for their own

information literacy writing, or trying to identify connection points between

information literacy and pedagogical discussions in the disciplines.

Literature Review

In 1992, Jacobson

and Vallely undertook a study to determine the prevalence and authorship of

articles about “library instruction” in the “journals that faculty members

read” (p. 360). They did not specify any subject area limitations in their

research, and the databases searched indicate that they included a wide range

of disciplines. The term “information literacy” was not yet in widespread use

in the period covered by their search (1980-1990), so they used “bibliographic

instruction” and other keywords and subject headings (outlined in detail in

appendix A of their article). They found 74 articles about library instruction

in non-library journals, with approximately 50% written by librarians alone,

25% written collaboratively by librarians and faculty members, and another 25%

authored by faculty members alone. Jacobson and Vallely expressed general

disappointment, not only with the small numbers, but also with the quality of

the articles retrieved, noting that there was “not much . . . novel or

surprising” (p. 360) in the articles by librarians, and that faculty-authored

articles revealed, “a remarkably superficial notion of who we [librarians] are

and what we do” (p. 362). They ended with a call for librarians to increase

publication about the value of library instruction in journals read by faculty

members.

Still’s 1998

article followed six years after Jacobson and Vallely’s early effort to use

non-library literature as a barometer for interest in and uptake of library

instruction. Like her predecessors, Still looked at subject-specific

pedagogical journals across disciplines, and found that only 33 of 13,016

articles discuss library instruction or library-related assignments. She

highlighted specific articles within four broad subject categories: Sciences,

Humanities, Social Sciences, and Nursing/Social Work, but did not characterize

the literature in any systematic way. In Sciences, the category most relevant

to the present study, she lauded the creation of the “Chemical Information

Instructor” column, edited by a librarian, in the Journal of Chemical

Education. Her conclusion, however, was sobering: “If the library and library instruction have been integrated into the

academic curriculum, there is little evidence of it in the discipline specific

teaching journals studied” (Still, 1998, p. 229).

Nearly a decade

after Still’s article, Stevens (2007) was the first author to analyze

discipline-specific pedagogical literature in the era of widespread adoption of

the term “information literacy” and the ACRL information literacy competency

standards. Even with the broadening of her focus from “library instruction” to

“information literacy,” Stevens found only 25 information literacy articles

published from 2000-2005 in the 54 pedagogy journals included in her study.

Like Jacobson and Vallely, Stevens was particularly interested in the

authorship of these 25 articles, and found that 7 were written by librarians,

12 were faculty/librarian collaborations, and 6 were written exclusively by

faculty. She concluded that, while information literacy had not made

significant inroads into the disciplinary pedagogy literature overall, there

were some bright spots. She noted the growing presence of information literacy

in the nursing pedagogy literature, presenting it as an example that

illustrates the value of publishing this work in disciplinary journals. Stevens

was also the first author to mention the ACRL standards in her analysis; while

she didn’t delve down to use of specific standards, she did note that some

articles, “use the ACRL Standards as a framework for

defining IL competencies, designing assignments, and assessing student

learning” (p. 262). Ultimately, like Jacobson and Vallely and also Stills,

Stevens concluded with a call for librarians (either alone or collaboratively

with faculty) to capitalize on the potential of discipline-specific pedagogy

journals to interest faculty in information literacy.

O’Connor (2008) was

the first, and to date only, author to conduct a more in-depth study of

information literacy in the literature of a specific discipline. She searched

business literature (broadly, not just pedagogical journals) in order to assess

the “diffusion” of information literacy in business studies. She located 159

relevant works (unlike previous studies, O’Connor included trade publications

in addition to scholarly journals) and her analysis revealed that

disappointingly few were written by librarians. She also developed and applied

a scale for delineating the extent to which the works addressed information

literacy topics, a scale that has been adopted for the current study. She found

that most of the information literacy articles she had identified gave the

topic “Incidental Mention,” although there were also a significant number in

which information literacy was the “Major Focus.” O’Connor’s application of

Rogers’ Diffusion of Innovations Theory led her to the conclusion that the low

and relatively stable level of information literacy publications appearing in

the business literature over time indicated that it is in the “earliest phases of adoption . . . and has not

yet reached the tipping point” (2008, p. 120).

The present study, like O’Connor’s work, is

based on the premise that detailed examination of the literature of specific

fields provides a deeper and more nuanced understanding of information

literacy, while also recognizing that there is value in being able to conduct

some comparisons among similar fields. It shares earlier authors’ interest in

the number of information literacy-related articles appearing in non-LIS

literature over time and their curiosity about the authorship of these

articles. It also offers a deeper level of analysis, not only characterizing

this body of literature by applying O’Connor’s levels, but also, for the first

time in this type of study, mapping journal articles to the ACRL information

literacy competency standards.

Aims

This study aims to answer the following

research questions: To what extent are information literacy competencies addressed by

science pedagogy journals? What is the nature of these references, in terms of

authorship, ACRL standards addressed, and degree of emphasis on information

literacy?

Methods

The term “information

literacy,” despite its widespread use among librarians, lacks a single,

accepted definition. Professional associations in different countries have

variously defined it as “knowing when and why you need information, where to

find it, and how to evaluate, use and communicate it in an ethical manner”

(Chartered Institute of Library and Information Professionals, 2004), or as

being “able to recognize when

information is needed and have the ability to locate, evaluate, and use

effectively the needed information” (American Library Association, 1989). The

author of this study used the ACRL’s five competency standards as the basis for

her definition and conceptualization of information literacy, primarily because

they have been so widely adopted in the North American academic library sector

where she works.

The researcher used

the 2011 Journal Citation Report (JCR) Science® edition to identify high

impact journals in the “Education—Scientific Disciplines” subject category.

While the problems inherent in using journal impact factors as a proxy for

journal quality have been well-documented (Lozano, Larivière, & Gingras 2012; McVeigh & Mann

2009, among others), this provided a

convenient way to identify journals across scientific disciplines whose reach

is significant, thereby serving the purpose of this study. The analysis included the 15 non-medical

journals with the highest impact factors, and the study considered articles

published in the most recent 10-year period for which complete data was

available (2002-2011), with the sample obtained in April 2013. Only articles

were included; editorials, news items, letters, and resource reviews were

excluded from the analysis. This created a large pool of 10,743 articles for

analysis, providing broad coverage across scientific disciplines, and covering

a time period of great change in information retrieval and usage practices. The

study used the online versions of the articles, relying on print only in cases

of missing content or access restrictions.

Efforts to identify

articles from this pool of 10,743 publications that address information

literacy-related topics were two-fold. The researcher initially conducted

keyword searches of Web of Science to identify occurrences of the terms

“information litera*” or “information fluen*” or “library instruction” or

“information competen*” from within the large pool of articles. She then

supplemented this by personally scanning the titles and, where necessary for

clarification, the abstracts and/or full text, of the original pool of 10,743

articles. This ensured the inclusion of relevant articles that did not contain

library-centric terminology in describing information-literacy related

concepts, as well as articles that focused on specific competencies (such as

plagiarism, searching) without including an umbrella information literacy term.

In an attempt to ensure consistency and quality control in the selection

process, the author selected only articles that could be correlated to specific

components of the ACRL competencies/ performance indicators/outcomes.

Additionally, articles had to focus on inculcating these competencies in

students, rather than mentioning them in other contexts. For example, an

article about instructor strategies for detecting plagiarism was also excluded

as the focus was not on educating students about the topic.

The researcher read

articles selected for inclusion in their entirety to ensure accurate

categorization. She created a standardized template in Excel and extracted data

from each article as it was read. The entry for each article included details

about the professional designations for every author in order to characterize

the authorship of this body of literature; in cases where this information was

not provided in the article, the researcher located it through Web searches

and, in a small number of cases, email follow-up. The template also required

entry of the publication year and the broad scientific subject area of the

journal in which each article was published. Additionally, the template also

required that the researcher classify each article according to the levels

developed by O’Connor to indicate the nature of the work’s attention to

information literacy concepts. The four levels are:

texts in which IL [information literacy] is

explicit and a major focus (IL–Major topic); texts in which IL is explicit and

treated substantively, but is not the focus of the article (IL-Substantive

Treatment); texts in which IL is explicit, but only mentioned in passing,

possibly with a very brief definition provided (IL–Incidental Mention); and

texts in which IL competencies are clearly being discussed, yet IL is never

explicitly named. (O’Connor 2008, p. 113)

Finally, the

template required the researcher to assign each article to the appropriate ACRL

information literacy competency standards for higher education (2000) to

provide more detailed insight into which standards are most frequently

addressed in this body of literature. The researcher coded articles as

addressing up to four individual standards, while coding those addressing all

five standards or information literacy generally as “IL—General.”

Results

A total of 10,743

journal articles met the criteria of articles published from 2002 to 2011 in

the target 15 journals. The researcher first reviewed article titles in order

to determine relevance of the papers, which revealed that the vast majority of

these did not address information literacy topics in any notable way. In 430

instances where titles were ambiguous or suggested information literacy-related

content, the researcher read abstracts to glean a better understanding of the

article. This allowed further refinement of the article set, and left 218

articles to be read in their entirety. Ultimately, only 156 of the original

10,743 articles (or 1.5%) addressed information literacy-related topics. The

names of the journals included in the analysis, the number of citations under

review from each journal, and the number/percentage of information

literacy-related references found in each journal are outlined in Table 1. These numbers clearly indicate that articles

on information literacy-related topics appeared only sporadically in science

pedagogy journals.

Table 1

Information Literacy Articles by Journal

|

Journal |

Total articles |

Number of information literacy articles |

% of information literacy articles out of

total |

|

Journal of Engineering Education |

228 |

6 |

2.6% |

|

Advances in Physiology Education |

358 |

15 |

4.2% |

|

Studies in Science Education |

52 |

1 |

1.9% |

|

CBE—Life Sciences Education |

325 |

18 |

5.5% |

|

IEEE Transactions on Education |

659 |

13 |

2.0% |

|

Physical Review Special Topics—Physics

Education Research* |

143 |

0 |

0 |

|

Journal of Science Education and

Technology |

459 |

13 |

2.8% |

|

Chemistry Education Research and Practice |

277 |

4 |

1.4% |

|

Biochemistry and

Molecular Biology Education |

566 |

19 |

3.4% |

|

European Journal of Physics |

1213 |

0 |

0 |

|

Journal of Chemical Education |

3057 |

39 |

1.3% |

|

American Journal of Physics |

1702 |

3 |

.2% |

|

International Journal of Engineering

Education |

1260 |

8 |

.6% |

|

International

Journal of Technology and Design Education |

198 |

7 |

3.5% |

|

Journal of Biological Education |

246 |

10 |

4.1% |

|

Total |

10,743 |

156 |

1.5% |

|

* Publication began in 2005 |

|||

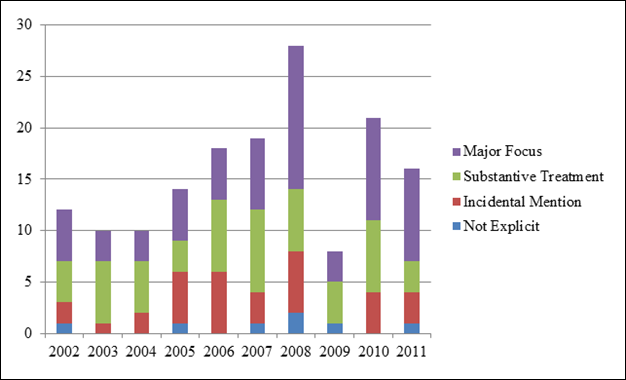

Journals were also

grouped according to specific scientific discipline, based on “Subject

Category” assigned in the 2011 Journal Citation Report (JCR) Science® edition, in an effort to

uncover any differences in the frequency of information literacy articles by

subject area. Figure 1 shows that, of the scientific disciplines represented in

the 15 journals under review, biology/life sciences journals were most likely to

have addressed information literacy topics (4.2% of articles). Science

(general), chemistry, and engineering journals published somewhat fewer

articles on information literacy topics, and information literacy articles were

virtually non-existent in the physics education literature, with only .2% of

journal articles under review addressing the topic.

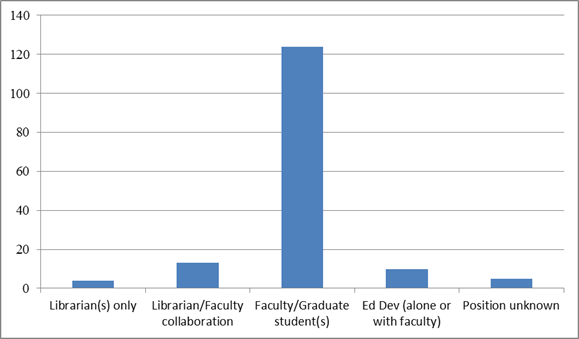

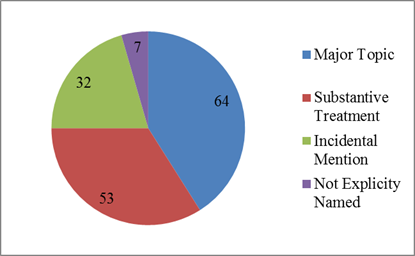

The researcher also

analyzed journal articles to determine the level or depth with which they focus

on information literacy topics. Application of the levels developed by O’Connor

(1998) revealed that, when addressed in science pedagogy journals, information

literacy is most frequently the “Major Topic” of a journal article, with

O’Connor’s category “IL Substantive Treatment” a close second (Figure 2). This is not to imply that the term

“information literacy” itself was used in the articles; in fact, this phrase is

absent in the vast majority of articles. Instead, it indicates that the concept

or its constituent parts (as articulated in the ACRL Information Literacy

Competency Standards for Higher Education) were represented at the

specified level. Thus, the category “IL Not Explicit” does not refer to the

absence of the term “information literacy,” but most often indicates that a

learning activity was developed to foster several skills, of which information

literacy is one.

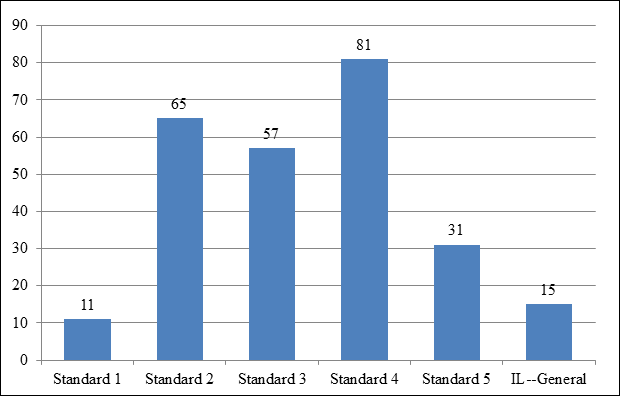

The researcher further

broke down the journal articles on information literacy-related topics by

publication year over the 10 year period. Figure 3 reveals a general increase

in the number of articles addressing information literacy topics from

2002-2008. After peaking in 2008, the number of articles on information

literacy topics declined precipitously in 2009, followed by a more gradual

decrease in 2010 and 2011. Figure 3 also reveals that over the years,

information literacy topics have become increasingly likely to be a “Major

Focus” of journal articles, whereas in the past there was a more even split in

the depth with which articles addressed the topic.

Figure 1

Information literacy

articles by subject area.

Figure 2

Number of articles by O'Connor level.