Article

Grey Literature Searching for Health Sciences

Systematic Reviews: A Prospective Study of Time Spent and Resources Utilized

Ahlam A. Saleh

Assistant Librarian Arizona

Health Sciences Library

University of Arizona

Tucson, Arizona, United

States of America

Email: asaleh@ahsl.arizona.edu

Melissa A. Ratajeski

Reference Librarian

Health Sciences Library System

University of Pittsburgh

Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, United States of America

Email: mar@pitt.edu

Marnie Bertolet

Assistant Professor

Graduate School of Public Health

University of Pittsburgh

Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, United States of America

Email: mhb12@pitt.edu

Received: 4 June 2014 Accepted: 7

Aug. 2014

![]() 2014 Saleh, Ratajeski, and Bertolet.

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative

Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

2014 Saleh, Ratajeski, and Bertolet.

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative

Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

Abstract

Objective – To identify estimates of time taken to search grey literature in

support of health sciences systematic reviews and to identify searcher or

systematic review characteristics that may impact resource selection or time

spent searching.

Methods – A survey was electronically

distributed to searchers embarking on a new systematic review. Characteristics

of the searcher and systematic review were collected along with time spent

searching and what resources were searched. Time and resources were tabulated

and resources were categorized as grey or non-grey. Data was analyzed using

Kruskal-Wallis tests.

Results – Out of 81

original respondents, 21% followed through with completion of the surveys in

their entirety. The median time spent searching all resources was 471 minutes,

and of those a median of 85 minutes were spent searching grey literature. The

median number of resources used in a systematic review search was four and the

median number of grey literature sources searched was two. The amount of time

spent searching was influenced by whether the systematic review was grant

funded. Additionally, the number of resources searched was impacted by

institution type and whether systematic review training was received.

Conclusions – This study characterized the amount of time for conducting systematic

review searches including searching the grey literature, in addition to the

number and types of resources used. This may aid searchers in planning their

time, along with providing benchmark information for future studies. This paper

contributes by quantifying current grey literature search patterns and

associating them with searcher and review characteristics. Further discussion

and research into the search approach for grey literature in support of

systematic reviews is encouraged.

Introduction

A properly conducted systematic review summarizes the

evidence from all relevant studies on a topic concisely and transparently

(Cook, Mulrow, & Haynes, 1997). The searches to support these reviews need

to be extensive often including extended searches of the grey literature.

Grey literature can be described in a number of ways,

but commonly has been defined by the 1997 Luxembourg Convention on Grey

Literature definition as literature: “which is produced on all levels of

government, academics, business and industry in print and electronic formats,

but which is not controlled by commercial publishers” (Farace, 1998, p.iii). In

2004, at the Sixth International Conference on Grey Literature, a postscript

was added to further expand on the “commercial publishers” aspects of this

definition. In recent years, the definition has stimulated new discussion due

to changes in the environment such as the evolving landscape of information

dissemination and the introduction of new avenues of scientific communication.

According to two-thirds of respondents in the Grey Literature Survey (Boekhorst, Farace, & Frantzen, 2005),

“Grey Literature is best described by the type of document it embodies” (p.6).

Some examples of grey literature include: reports, conference abstracts,

dissertations, and white papers (GreyNet International, 2013).

Systematic review support seems to be of growing

interest to health sciences information professionals. A 2013 survey of

librarians and directors about emerging roles of biomedical librarians found

that support of systematic reviews was one of the top six most common reported

new roles (Crum & Cooper, 2013). Furthermore, in a 2013 systematic review

of the literature from 1990-2012 on changing roles for health sciences

librarians, systematic review librarian was identified as one of the newer

roles in the field (Cooper & Crum, 2013).

In recent years, education opportunities relating to

systematic review searching have transpired. This is no surprise, given that

information professionals planning to get involved in systematic reviews would

need to familiarize themselves and learn more about the process and

specifically about the search process, as it is distinct from routine

literature searches. As an example of

these emerging education opportunities, a search of the Medical Library

Association’s Educational Clearinghouse (http://cech.mlanet.org/), found eight

Continuing Education (CE) courses with the words “systematic review” in the title,

and there were at least three CE courses found listed on the Canadian Health

Libraries Association website (http://www.chla-absc.ca/node/119). Systematic

review as a topic is also emerging in library science curricula as can be found

in select content covered in the Certificate of Advanced Study in Health Sciences

Librarianship (HealthCAS), Reference Services and Instruction in Healthcare

Environments course previously offered through the University of Pittsburgh.

The University of Alberta, School of Library Information Studies has a course

entitled “Systematic Review Searching”, and the Texas Woman’s University

medical library curriculum planned a

course for systematic reviews that would

be launched in Spring 2014 (C. Perryman, personal communication, July 7,

2013).

In 2011, the Institute of Medicine (IOM) released

standards for systematic reviews which indicate that researchers should “take

action to address potentially biased reporting of research results” (p.84). To

address this bias, Standards 3.2.1 and 3.2.4 call for the inclusion of grey

literature searches in all systematic reviews and handsearching of selected

journals and conference abstracts (Institute of Medicine [IOM], 2011). These

standards may lead to wider acceptance of including grey literature searching

in systematic review methodology. As librarians

become increasingly integrated into systematic reviews, as called for by the

IOM Standard 3.1.1 which specifically states “Work with a librarian or other

information specialist trained in performing systematic reviews to plan the

search strategy”, they must be prepared to search the grey literature or at

least provide guidance on resources and search strategies (IOM, 2011,

p.84). Locating grey literature can

often be challenging, requiring librarians to utilize a number of databases

from various host providers or various websites, some of which they may not be

familiar with or aware of. Additionally,

searchers may need to spend time learning various search interfaces and the

nuances of each resource, such as how to download references or if the search

query boxes have term limits (Wright,

Cottrell, & Mir, 2014).

Investigation into the grey literature search process

for systematic reviews may reveal useful information that can be applied by

information specialists planning and preparing for systematic review searches.

There is limited information on the time it takes to search grey literature in

support of systematic reviews and we are not aware of any studies which relate

searcher or systematic review characteristics to either time spent searching

the grey literature or which grey literature resources are selected for the

search. Therefore, we sought to explore these aspects of the process of grey

literature searching in support of systematic reviews.

Literature Review

Acceptance of the inclusion of grey literature in

systematic reviews has varied over time. A 2006 survey showed approximately 90%

of systematic reviewers and approximately 70% of editors felt grey literature

probably or definitely should be eligible for inclusion in systematic reviews,

while a prior 1993 survey showed that 78% of meta-analyst and methodologist

respondents felt that unpublished material should definitely or probably be

included in systematic reviews, and that only 47% of journal editors felt this

way (Cook et al., 1993; Tetzlaff, Moher, Pham, & Altman, 2006). The biggest

concerns were about the lack of peer review and quality of the studies found in

the grey literature. However, other studies detail the benefit of including

grey literature in systematic reviews (Crumley, Wiebe, Cramer, Klassen, &

Hartling, 2005; Savoie, Helmer, Green, & Kazanjian, 2003). Two Cochrane

reviews further support why it is important to search for grey literature. A

2007 Cochrane systematic review on the use of grey literature in meta-analyses

of randomized trials found that non-grey literature trials tended to be larger

and showed an overall larger treatment effect when compared to grey literature

trials (Hopewell, McDonald, Clarke, & Egger, 2007). Another Cochrane

systematic review on time to publication for results of clinical trials found

that positive result trials tended to be published earlier than negative or

null result trials and positive result trials were more likely to be published

than negative or null result trials (Hopewell, Clarke, Stewart, & Tierney,

2007). Therefore, when conducting searches for systematic reviews searching for

grey literature may be used as a means to minimize the introduction of bias

such as publication and time-lag bias.

There is a time cost for including a grey literature

search in a review. How much time is difficult to estimate however and, because

librarians in an academic or hospital role are often juggling other

responsibilities, time management is crucial.

There seems to be limited research specifically reporting on the time

taken to conduct literature searching for systematic reviews. If time is

reported, it is often grouped with other tasks such as article retrieval and

screening, or the search time is listed as one number, not denoting the time

differences for various resources such as PubMed vs. a grey literature resource

such as ClinicalTrials.gov. In an examination of 37 meta-analyses, Allen and

Olkin (1999) found that the average systematic review took 1139 hours to

complete (with a range of 216 to 2518 hours). Of this time, 588 hours accounted

for protocol development, searches, retrieval, abstract management, paper

screening, blinding, data extraction and quality scoring and data entry. In a

single meta-analysis conducted by Steinberg et al. (1997), a description of the

time to complete various systematic review tasks, including screening,

extracting data, and writing the manuscript was reported. They estimated the

total hours for conducting the review to be 1046 hours (26 weeks) of which 24

hours was used to conduct the literature search. Guise and Viswanathan (2011)

estimate that it would take 1-4 weeks to run comparative effectiveness review

searches.

Greenhalgh and Peackock (2005) reported the time taken

for electronic database searches for their systematic review (including

developing the search, refining, and adapting to other databases) as

approximately two weeks of a librarian specialist’s time. This article also

looked at how productively the time was spent. The two weeks of a librarian’s

time “yielded only about a quarter of the sources - an average of one useful

paper every 40 minutes of searching” (Greenhalgh & Peacock, 2005, p. 1065).

Greenhalgh and Peackock (2005) go into further detail and compares electronic

searching with handsearching. A handsearch of 271 journals took approximately a

month of time resulting in 24 papers that were included in the final report –

“an average of one paper per nine hours of searching” (Greenhalgh &

Peacock, 2005, p. 1065).

Using traditional electronic databases to search the

literature does not always identify all relevant studies. This can be due to a

number of reasons including lack of appropriate indexing terms, lack of

indexing all sections of a journal, or research methods not being fully

described in the abstract (Hopewell, Clarke, Lefebvre, & Scherer, 2007). Therefore

handsearching of journals or conference proceedings would be particularly

relevant to include in the systematic review search methodology. The Cochrane

Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions defines handsearching as

follows: “Handsearching involves a manual page-by-page examination of the

entire contents of a journal issue or conference proceedings to identify all

eligible reports of trials” (Cochrane Collaboration, 2011, Section 6.2.2.1).

Handsearching of conference proceedings could be considered as a type of grey

literature searching.

Studies other than Greenhalgh and Peackock have also

looked at the time required for handsearching. Additional reported time ranged

from 30 minutes per journal issue to 45 minutes - 3 hours per year of a title

and this may vary based on subject matter (Adams, Power, Frederick, &

Lefebvre, 1994; Armstrong, Jackson, Doyle, Waters, & Howes, 2005; Croft,

Vassallo, & Rowe, 1999; Jadad, Carroll, Moore, & McQuay, 1996).

There are a variety of studies that have examined how

characteristics such as search experience, relate to search quality, search

speed, search effectiveness and the search process (Al-Maskari & Sanderson,

2011; Debowski, 2001; Fenichel, 1981; Hsieh-Yee, 1993; Kuhlthau, 1999). Many of

these studies seem to focus on varying experience levels within end-user

groups. Though, Tabatabai and Shore (2005) explored how experts (highly

experienced librarian professionals), intermediates (final year master of

library information studies students) and novices (undergraduate teachers)

searched the Web. Significant differences in patterns of search among the

different groups were found in cognition, metacognition, and prior knowledge

strategies (Tabatabai & Shore, 2005). Previous literature also demonstrates

interest in exploring different experience levels in relation to performance of

a systematic review. A study (Riaz, Sulayman, Salleh, & Mendes, 2010)

reporting on systematic reviewers noted that new systematic reviewers

experienced problems with time taken to conduct the review, defining the

research question and inclusion/exclusion criteria, and data management that

were not faced by experienced systematic reviewers. Given this insight from the

literature, it seems useful to consider subject characteristics as variables

that may potentially impact outcome searches.

Aims

The purpose of this study was to explore grey

literature searching for health sciences systematic reviews. More specifically:

- To

explore the time taken to conduct grey literature searches for systematic

reviews

- To

explore the resources selected for grey literature searches for systematic

reviews

- To

evaluate whether any relationship exists between searcher and systematic

review characteristics and time to search or number of resources selected

for grey literature searches in support of systematic reviews

Methods

Study Recruitment

University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board

(IRB) approval was obtained to conduct the study. Participants were recruited

through listservs, social media and email contacts. A total of 19 listservs,

including information professional types and those whose subscribers were

thought to have an interest in systematic reviews, were used for recruitment.

Social media sources included posting on Facebook, posting on popular librarian

blogs, and having fellow librarians post tweets. The prerequisite for study

enrolment was: the participant must currently be embarking on a literature

search to support a systematic review or plan to in the near future. However,

searching should not have taken place prior to enrolment. The searcher did not

have to be a librarian but had to be the person responsible for building the

searches and running them in each database used.

Data Collection

A survey instrument was developed and pilot tested on

a small sample which included two systematic review course instructors (a

clinician and a biostatistician) and five information specialists. Revisions to

the survey forms were made based on feedback. The survey forms were distributed

in two parts (see Appendix for surveys). Part one of the survey collected

demographic information about the searcher and their systematic review

experience and was required to be submitted directly after study enrolment.

Part two of the survey was provided to participants after they submitted part

one. Return of the part two form was expected upon completion of the systematic

review searches. This part of the survey collected information about the

systematic review including topic, population, and if the systematic review was

grant funded. Participants were also asked to document the name of the

resources searched, platform or vendor of the resource, resource URL when

applicable, and the time taken to search the resource (electronic database,

website searching or handsearching). Reported time was to account for choosing

terminology, developing the strategy, refining and running the search.

In order to minimize the potential of bias in the

searching, it was not disclosed to subject participants that this was a survey

specifically focused on grey literature searching in systematic reviews.

Rather, participants were asked to include all resources searched for the

systematic review including handsearching. Other means of searching for

studies, such as citation tracking (i.e. snowballing) or contacting key authors

or experts were not specifically requested in our data collection form.

Email reminders were sent twice to participants who

did not submit their completed data forms.

Data Analysis

From the completed surveys, a list of the resources

participants used in their systematic review searches was compiled. For some

resources various interfaces were used to complete the search i.e. OVID MEDLINE

vs. PubMed. In these cases the resources were classified as the same despite

the interface used with the exception of Cochrane Library and the Centre for

Review and Dissemination (CRD) resources. Some users searched both Cochrane

Library and the CRD version of the databases: Database of Abstracts of Reviews

of Effects (DARE), NHS Economic Evaluation Database (NHSEED) and Health

Technology Assessment (HTA), for the same review. Cochrane Library individual

resources were all grouped under “Cochrane Library,” and if a CRD search

platform was also used, that resource was categorized separately as “CRD

database.”

Once the list of resources was compiled, each resource

was labeled as grey literature or non-grey literature. To categorize the

resources, the librarian authors used the 1997 Luxembourg definition of grey

literature, reviewed the database content, contacted the database content

producers as necessary, and used their own expert opinion. Resources that

predominately included literature from journals were categorized as non-grey.

Resources that included citations mostly from book chapters, theses, reports,

conference materials or other type of grey literature were categorized as grey.

Because many resources may cover both grey and non-grey literature for these

resources, assignment of grey vs. non-grey was based on the authors’ estimation

of which type of content was the majority. Handsearching was denoted as a grey

literature resource because conference proceedings were primarily handsearched

for participant systematic reviews which included handsearching. Once

categorization was completed, the number of grey literature vs. non-grey

literature resources and the time taken to search each type of resource was

tallied.

The six outcomes analyzed were the number of grey,

non-grey and total literature resources along with the amount of time searching

each of those resources. These outcomes were compared across the searcher and

the systematic review characteristics. Continuous variables were compared

across groups using a Kruskal-Wallis test instead of a t-test because

non-normality in some of the variables violated t-test assumptions. Boxplots

comparing the amount of time searching the literature across groups were

graphed on the log scale due to a few extremely large values. Kruskal-Wallis

tests were performed on the log scales for the amount of time searching the

literature across groups to be consistent with the boxplots. Sensitivity

analysis without the log transformations yielded similar results.

Results

Out of 81 initial respondents, 17 (21%) completed both

parts of the study and were included in the data analysis. Nineteen respondents

were excluded because they did not meet the study prerequisites. The remaining

respondents withdrew from the study or did not complete both parts of the

survey. Of the 17 final participants, 15 reported that their primary

professional role was a librarian/information professional.

Searcher Characteristics

Most study participants were from an academic

environment (Figure 1). Hospital was reported by 24% and Other, which included

one non-government agency and one independent research company, made up 11% (n=

2) of participants’ institution. The participant country representation was

mostly comprised of United States (US), Canada, and the United Kingdom (UK)

with a few additional countries represented by Other (Figure 2).

Figure 1

Type of institution where searcher was employed (n= 17).

Figure 2

Country where searcher was employed (n= 17).

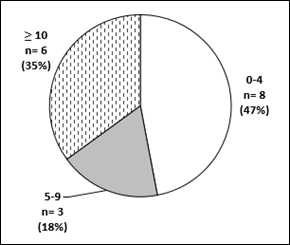

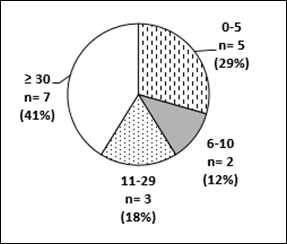

Figures 3 and 4 show that most study participants had

greater than 10 years of experience in their profession and at least 5 years of

experience in assisting in systematic reviews. The number of systematic review

searches that respondents had contributed to ranged from 0 to greater than 50

(Figure 5).

Figure 3

Searchers’ years of experience in profession

(n= 17).

Systematic Review Characteristics

Half of the searchers responded that they would be a

co-author on the systematic review that they completed the searches for, while

the others responded they would not (33%) or were not sure (17%).

With regards to study population, the survey asked about

age of the target population. Thirty-nine percent of the systematic reviews

focused on adults, 17% pediatric, and 44% focused on both. The breakdown for

the methodological focus of the systematic reviews included Therapy (33%),

Diagnosis (11%), Prognosis (11%), Other (39%), and Unsure (6%).

An attempt was made to explore whether any relationships existed between systematic review topic

and time spent searching and resources used. However, because of the wide range

of topics for a small sample size, we were not able to analyze the data in a

meaningful way.

Most of the reviews were completed under the guidance

of a systematic review producing entity (56%; n= 18). Also the majority of

systematic reviews were not grant funded (67%) (Figure 6).

Figure 4

Searchers’ years of experience contributing to systematic reviews (n= 17).

Figure 5

Number of systematic reviews

searcher has contributed to in the past (n= 17).

Figure 6

Grant funded systematic

reviews (n= 18).

Time Spent Searching and Number of Resources Searched

Tables 1 and 2 show the time survey participants

reported searching resources for their systematic review and the mean number of

resources used per systematic review.

Using the Kruskal-Wallis test we examined whether the

time spent searching resources for a systematic review or the number of

resources used for a systematic review search varied by the characteristics of

a systematic review (grant funded, under guidance of a systematic review

producing entity, etc.) or of an individual searcher (institution, country,

systematic review training, etc.).

Figures 7-10 use boxplots to visualize the

statistically significant (p ≤ 0.05) findings. In the boxplots the thick dark horizontal

line represents the median value. The bottom and top of the box are the first

(Q1) and third (Q3) quartiles where 25% of the data is below Q1 and 75% is

below Q3. The “whiskers” extending from the boxes show the spread of the data

with outliners represented as dots (as in Figures 9 and 10).

The time spent

searching can be obtained by exponentiating the log (minutes) in Figures 7 and

8. Specifically, whether or not the systematic review was grant funded was

associated with the amount of time spent searching for both grey literature

(median [Q1, Q3] for grant funded: 544.5 [211.4, 1339.4] minutes and not grant

funded: 66.7 [36.6, 109.9] minutes, p=0.03)

and non-grey literature (median [Q1, Q3] for grant

funded: 1480.3 [365.0, 3294.5] minutes and not grant funded: 270.4 [164.0,

492.7] minutes, p=0.05) (Figures 7 and 8). The number of resources searched for

the systematic reviews varied by the searchers’ institution (median [Q1-Q3] for

academic: 2.5 [2.0, 4.5]; hospital: 1.0

[1.0, 1.3]; and Other: 8.5 [7.8, 9.3], p=0.02) and whether the searcher

received systematic review training (median [Q1-Q3] for trained: 3.0 [3.0,

5.0]; and untrained: 6.0 [4.0, 7.0], p=0.045) (Figures 9 and 10).

Resources Searched

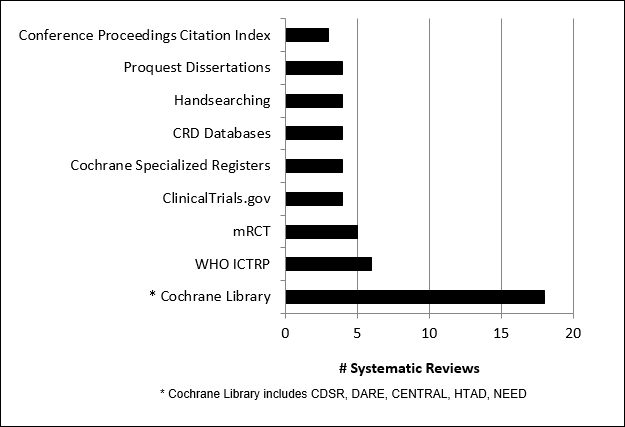

Figures 11 and 12 show the most common grey and

non-grey literature resources reported as being used by the 17 study

participants.

Discussion

The results of this study found that the average total

time spent searching electronic databases and handsearching the literature for

a systematic review was 24 hours with a range of 2 to 113 hours with 50% of the

participants reporting spending less than 8 hours. Our study also more

specifically identified time taken to search the grey literature for a

systematic review. All systematic reviews reported (n= 18) included some form

of grey literature searching. The average time taken to conduct the grey

literature search was approximately 7 hours, with range of 20 minutes to 58

hours, with 50% of the participants reporting spending less than 1.5 hours. The

grey literature search represents 27% of the total time of the literature

search on average, with 50% of the participants spending 20% or less of their

time searching grey literature.

Table 1

Time Spent Searching Resources for Systematic Review

Searches

|

|

Time Range (minutes) |

Time Mean (minutes) |

Time Median (minutes) |

Quartiles (Q1,Q3) |

|

Grey Literature Resources |

20-3480 |

395 |

85 |

(45,240) |

|

All Resources |

96-6780 |

1457 |

471 |

(255,2104) |

Table 2

Number of Resources Utilized for Systematic Review

Searches

|

|

Resources Range (number) |

Resources Mean (number) |

Resources Median (number) |

Quartiles (Q1,Q3) |

|

Total Resources Searched |

3-27 |

9 |

8 |

(5,10) |

|

Grey Literature Resources Searched |

1-14 |

4 |

2 |

(1.25,5.5) |

|

Non-Grey Literature Resources Searched |

2-13 |

5 |

4 |

(3,5.75) |

Figure 7

Time spent searching grey literature for a systematic

review (n= 17).

Figure 8

Time spent searching non-grey literature for a

systematic review (n=17).

Figure 9

Number of grey literature resources used for a

systematic review (n= 18).

Figure 10

Number of non-grey literature resources used for a

systematic review (n= 18).

Figure 11

Top grey literature resources searched for a

systematic review (n= 18).

Figure 12

Top non-grey literature

resources searched for a systematic review (n= 18).

When reporting time spent searching, survey

respondents were asked to account for choosing terminology, developing the

strategy, refining, and running the search. Depending on how the instruction

“running the search” was interpreted response times could be skewed low.

Although not specifically stated, we aimed to have the time requested on the

survey to capture the time required for searchers to navigate and learn the

nuances of the databases used for grey literature searching as they prepare the

search approach. Grey literature electronic resources are often limited and

crude in search capability. Truncation of terms may not be possible, search

boxes may be limited in the number of characters they accept, little or no search

help documentation may be provided and no export feature may be available.

Because of these limitations the searcher may spend more time searching the

database than anticipated. Grey literature resources are also not routinely

searched by the average health sciences librarian for everyday work. Because of

this, database unfamiliarity may also require searchers to spend more time

searching the grey literature.

As previously mentioned, all reviews reported included

some form of grey literature searching. An average of four grey literature

resources were searched per review, with a range of one to 14 resources and

with 50% of the participants reporting using one or two grey literature

resources. The number of resources selected for the grey literature search may

be restricted due to time constraints if there is pressure to complete the

systematic review within a short time period. Also resource selection may be impacted

by resource access which may be limited depending on institutional

subscriptions. We did not ask searchers what, if anything, impacted or limited

the number of resources selected, especially for grey literature. We did ask if

a resource was purchased as a one-time paid subscription for purposes of a

search for the systematic review, however no respondents reported this to be

the case. Locating resources to search for grey literature is important and

worth noting as one of the challenges with searching the grey literature. It is

possible that problems locating grey literature resources impacted the number

of resources used by participants in the study.

As shown in Figures 11 and 12, MEDLINE and Cochrane

Library were used in all the reviews reported in this study. Following the

Cochrane Library, the next most commonly used grey literature resources were

the World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform

(WHO ICTRP) (n= 6) and the metaRegister of Controlled Trials (mRCT) (n= 5).

It is not surprising that the Cochrane Library,

produced by the Cochrane Collaboration, led the ranking of the grey literature

resource searched. The Cochrane Collaboration, which recently celebrated their

20th anniversary is widely known for generating systematic reviews

and is respected by both researchers and librarians alike (Friedrich, 2013).

The Cochrane Library provides access to the CENTRAL database, which includes

randomized and controlled clinical trials obtained not only from electronic database

searches but also from the journal and conference proceeding handsearching

efforts of the Cochrane Collaboration. Furthermore, the Cochrane Library

includes access to the HTA database and the NHSEED which contain indexed

reports. . For this reason, the Cochrane Library was classified as a source of

grey literature for the purpose of this study. It should be noted that 56% of

the systematic reviews reported in this survey were conducted under the

guidance of a systematic review entity. This may include the Cochrane

Collaboration, for which documentation in the editorial policies requires the

search of CENTRAL for all Cochrane Systematic Reviews (Chandler, Churchill,

Higgins, Lasserson, & Tovey, 2013). It is possible that this could have

influenced why the Cochrane Library was found to be the top grey literature

resource used. The two grey literature resources that were the next most

commonly used were the WHO ICTRP and mRCT. Both of these resources allow

federated searching across multiple trial registries including

ClinicalTrials.gov. Searching such resources would ideally reduce the need to

search several trial registries, a possible explanation for their appearance in

our top grey literature resources searched list and perhaps why they may have

appeared higher on the list compared to ClinicalTrials.gov.

Also evaluated was whether time spent searching or the

number of resources selected varied by searcher or review characteristics. As

shown in Figures 7 and 8 the amount of time spent searching for both grey and

non-grey literature was impacted by whether or not the systematic review was

grant funded. More time was spent searching both types of resources if the

systematic review was grant funded. The explanation for this finding is

unclear. It may be that there are differences as to how funded systematic

reviews are conducted compared to non-funded systematic reviews. A 2007 study

(Reed et al., 2007) on the association of funding and quality of published

medical education research found differences in the quality of funded studies.

Perhaps a funded systematic review has more resources available in terms of

manpower and technology because of funding.

Another finding was that the number of resources

searched was impacted by the searcher characteristics. The number of literature

resources varied by institution (academic, hospital or other). When performing

all two-way comparisons, we found that those who work in academic settings used

fewer grey literature resources than those who work in other settings (p =

0.03) and that those who work in hospitals use fewer numbers of grey literature

resources than those who work in other settings (p = 0.049). Academic- and

hospital-affiliated information professionals are often juggling a multitude of

responsibilities and therefore may not have as much time to devote to each

systematic review search and therefore it is possible that this leads to fewer

grey literature resources being used in the search. The number of non-grey

literature resources searched also varied by whether the individual received

systematic review training. If systematic review training was received, the

number of non-grey literature resources was decreased. It is unclear why such a

relationship is evident. Perhaps those with training can more readily select

the pertinent databases for the systematic review topic or feel more confident

with being selective. Our survey cannot conclude this however. Searchers with

less training may take precaution and therefore select a large number of

resources to search and spend a long time searching. Again, there is no certain

explanation for our results. Many variables may contribute, including whether

there is a fair amount of time allotted to locating studies.

Limitations

There are several limitations in this study that are

worth noting. We utilized convenience sampling, recruiting mainly through known

listservs. Of the respondents who started the survey, only 21% completed the

survey. The reasons for this non-completion are not known, although it is

possible that the second part of the survey was viewed as too onerous or that

the planned systematic review never progressed to the searching phase. There

was limited power in the analysis due to the small sample size, so results

should be viewed as suggestive rather than predictive. Also, because the small

sample size consisted of mainly library professionals, results may not be

generalizable to all those undertaking a systematic review search. Part two of

this survey study utilized prospective methodology, asking participants to

record information about their systematic review searching as they worked.

Perhaps if a retrospective methodology was used more potential participants

would have met our inclusion criteria, resulting in a larger sample size.

However, it was the feeling of the authors that a prospective survey would

allow the least biased capture of time spent searching. A further limitation

regarding methodology of the study was the subjective categorization of

resources into grey literature or non-grey literature by the authors.

The time for searching that we obtained through this

study may be underreported due to the following: five survey participants

reported that a portion of the searching was completed by another individual

but only reported the name of the resource, not time spent searching. Two

survey participants did not report the time spent searching each resource

individually; they only reported the total time as whole which was spent

searching all resources for the review.

Future Directions

This study draws attention to the need for further

research on search methodology in systematic reviews and grey literature.

Furthermore, there is a need for guidelines on conducting systematic review

searches including grey literature searching. Some earlier literature

demonstrates searchers’ recognition of issues with searching grey literature,

and with the approach to searching for comprehensive literature reviews. In a Canadian report (Dobbins, Robeson, Jentha &

DesMeules, 2008), a methodology for the grey literature search to support

evidence syntheses in public health was explored. Tyndall (2008) opens up

discussion of the grey literature search process by suggesting a hierarchy for

acceptable grey literature. Bidwell‘s COSI model (Bidwell & Jensen, 2003),

a model proposed for searches to support technology assessment reports is an

example of an approach that can be revisited to address this matter. The COSI

model relates to the whole search process and uses a framework or protocol to

categorize resources into three levels of priority based on expectation of

yield. The acronym COSI, and levels of priority, include CO for core search, S

for standard search, and I for ideal search (Bidwell & Jensen, 2003). If

there is sufficient time to undertake the search, the Ideal search of resources

is proposed. Information professionals conducting searches for systematic

reviews have little guidance to assist them with the approach and how to

conduct the searches. For information specialists embarking on systematic

review searches, questions may arise as to which resources to search, how many,

how far to go in breadth of resources. Perhaps, a similar concept to the COSI

model can be used to develop a framework for guidance in grey literature

searching in support of systematic reviews.

Hopewell, McDonald, et al. (2007) found that studies

included in systematic reviews, located through grey literature searching, were

more commonly conference abstracts or unpublished data (trial registers, file

drawer data, data from individual trialists). Additional types of grey

literature identified in the review include: book chapters, unpublished

reports, pharmaceutical company data, in press publications, and letters and

theses (Hopewell, McDonald, et al., 2007). The study findings could potentially

be used to support development of a framework that would prioritize resources

by the document types that they include, with the thought that certain types of

documents are more often found useful for inclusion into systematic reviews.

The aforementioned are just several examples for illustration purposes. A more

national/international collaborative effort by an authoritative body would be

best to propose systematically developed guidance.

It should be noted that a number of guides exist which

list grey literature resources to search and explain the importance of

searching grey literature (Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in

Health, 2013; Centre for Reviews and Dissemination, 2009; Cochrane

Collaboration, 2011). Many of these guides can be helpful to identify possible

resources but some are merely lists, and while some explain the importance of

select types of items they do not highlight an approach or framework for

following through with the entire grey literature search process. Furthermore,

only a select few are designed specifically for information professionals.

Exploration of the systematic review search process

regarding grey literature including time taken to search, resources used, and

investigation of any relating characteristics which may impact these factors is

one step forward toward engaging the health sciences library community in

further discussion about grey literature. Many information professionals are

multi-tasking, such as is the case with academic health science librarians and

hospital librarians, and therefore time management is of great interest in

order to efficiently integrate systematic review searching into one’s routine

responsibility.

Conclusion

We sought to prospectively explore the time taken to

conduct grey literature searches, via electronic database searching and

handsearching, for systematic reviews and to evaluate whether any relationship

exists between searcher and systematic review characteristics. The mean time

taken to conduct grey literature searches was approximately 7 hours, with 50%

of the searchers reporting less than 1.5 hours spent. This mean time represents

27% of the total time taken to complete the systematic review literature search.

Time spent searching both the grey and non-grey literature was influenced by

whether or not the systematic review was grant funded. The time estimates given

in this study are for searching-related activities only and do not include

other potential librarian efforts involved in participating in the synthesis of

a review such as meetings with the review requestor and the systematic review

team and managing citations. However, the time estimate provided for searching

both the grey literature and non-grey literature resources can provide

direction for librarians when meeting with researchers, writing a grant for a

completing a systematic review, or simply managing their own time. The top

resources used by the participants in this study might provide a reference

point for librarians working on a systematic review.

In light of recently established systematic review

standards, we expect some changes in the landscape of systematic review

searching. Additionally, we hope that in the near future grey literature

searching standards for systematic reviews are developed by the librarian

community for information professionals.

Acknowledgements

This project is supported in part by the National

Institutes of Health through Grant Numbers UL1 RR024153 and UL1TR000005.

We would like to thank Dave Piper for review of the

manuscript.

References

Adams, C. E., Power, A., Frederick, K., & Lefebvre, C. (1994). An

investigation of the adequacy of MEDLINE searches for randomized controlled

trials (RCTs) of the effects of mental health care. Psychological Medicine, 24(3), 741-748. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0033291700027896

Al-Maskari, A., & Sanderson, M. (2011). The effect of user

characteristics on search effectiveness in information retrieval. Information Processing & Management, 47(5),

719-729. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ipm.2011.03.002

Armstrong, R., Jackson, N., Doyle, J., Waters, E., & Howes, F.

(2005). It's in your hands: the value of handsearching in conducting systematic

reviews of public health interventions.

Journal of Public Health, 27(4), 388-391. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/pubmed/fdi056

Bidwell, S., & Jensen, M. F. (2003). Using a search protocol to

identify sources of information: the COSI model. Etext on Health Technology

Assessment (HTA) Information Resources. In National

Information Center on Health Services Research and Health Care Technology

(NICHSR). Retrieved from http://www.nlm.nih.gov/archive/20060905/nichsr/ehta/chapter3.html

Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health. (2013). Grey

matters: a practical deep-web search tool for evidence-based medicine, Retrieved from http://www.cadth.ca/media/pdf/Grey-Matters_A-Practical-Search-Tool-for-Evidence-Based-Medicine.doc

Centre for Reviews and Dissemination. (2009). Systematic reviews: CRD's

guidance for undertaking reviews in healthcare. Retrieved from http://www.york.ac.uk/inst/crd/pdf/Systematic_Reviews.pdf

Chandler, J., Churchill, R., Higgins, J., Lasserson, T., & Tovey, D.

(2013). Methodological standards for the conduct of new Cochrane Intervention

Reviews. In Cochrane Editorial Unit

(Ed.) Methodological Expectations of

Cochrane Intervention Reviews (MECIR) |

Retrieved from http://www.editorial-unit.cochrane.org/sites/editorial-unit.cochrane.org/files/uploads/MECIR_conduct_standards%202.3%2002122013.pdf

Cochrane Collaboration. (2011). In J. P. T. Higgins

& S. Green (Eds.) Cochrane Handbook

for Systematic Reviews of Interventions,

Retrieved from http://www.cochrane-handbook.org

Cook, D. J., Guyatt, G. H., Ryan, G., Clifton, J.,

Buckingham, L., Willan, A., McIlroy, W., Oxman, A. D. (1993). Should

unpublished data be included in meta-analyses? Current convictions and

controversies. Journal of the American

Medical Association, 269(21), 2749-2753. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/jama.1993.03500210049030

Cook, D. J., Mulrow, C. D., & Haynes, R. B.

(1997). Systematic reviews: synthesis of best evidence for clinical decisions. Annals of Internal Medicine, 126(5),

376-380. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-126-5-199703010-00006

Cooper, I. D., & Crum, J. A. (2013). New

activities and changing roles of health sciences librarians: a systematic

review, 1990-2012. Journal of the Medical

Library Association, 101(4), 268-277. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.3163/1536-5050.101.4.008

Croft, A. M., Vassallo, D. J., & Rowe, M. (1999).

Handsearching the Journal of the Royal Army Medical Corps for trials. Journal of the Royal Army Medical Corps, 145(2),

86-88. doi: dx.doi.org/10.1136/jramc-145-02-09

Crum, J. A., & Cooper, I. D. (2013). Emerging

roles for biomedical librarians: a survey of current practice, challenges, and

changes. Journal of the Medical Library

Association, 101(4), 278-286. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.3163/1536-5050.101.4.009

Crumley, E. T., Wiebe, N., Cramer, K., Klassen, T. P.,

& Hartling, L. (2005). Which resources should be used to identify RCT/CCTs

for systematic reviews: a systematic review. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 5, 24. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-5-24

Dobbins, M.,Robeson, P,Jentha, N., & DesMeules , M (2008).

Grey Literature: A methodology for searching the grey literature for

effectiveness evidence syntheses related to public health: A report from

Canada.Health Inform, 17(1), 9-12.

Farace, D. J. (1998). Forward. In D.J. Farace

(ed.). GL'97 Conference Proceedings: Perspectives

on the Design and Transfer of Scientific and Technical Information, Amsterdam: TransAtlantic.

Fenichel, C. H. (1981). Online searching: Measures that

discriminate among users with different types of experiences. Journal of the American Society for

Information Science, 32(1), 23-32. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/asi.4630320104

Friedrich, M. J. (2013). The Cochrane Collaboration

turns 20: Assessing the evidence to inform clinical care. Journal of the American Medical Association, 309(18), 1881-1882.

doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/jama.2013.1827

Greenhalgh, T., & Peacock, R. (2005).

Effectiveness and efficiency of search methods in systematic reviews of complex

evidence: audit of primary sources. British

Medical Journal, 331(7524), 1064-1065. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmj.38636.593461.68

GreyNet International. (2013). Document types in grey

literature. Retrieved 07/09/2013, from http://www.greynet.org/greysourceindex/documenttypes.html

Guise, J.-M., & Viswanathan, M. (2011). Overview

of best practices in conducting comparative-effectiveness reviews. Clinical Pharmacology &Therapeutics, 90(6),

876-882. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/clpt.2011.239

Hopewell, S., Clarke, M.J., Lefebvre, C., &

Scherer, R.W. (2007). Handsearching versus electronic searching to identify

reports of randomized trials. In Cochrane

Database of Systematic Reviews, MR000001. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/14651858.MR000001.pub2

Hopewell, S., Clarke, M.J., Stewart, L., &

Tierney, J. (2007). Time to publication for results of clinical trials. In Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews,

MR000011. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/14651858.MR000011.pub2

Hopewell, S., McDonald, S., Clarke, M.J., & Egger,

M. (2007). Grey literature in meta-analyses of randomized trials of health care

interventions. In Cochrane Database of

Systematic Reviews, MR000010. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/14651858.MR000010.pub3

Hsieh-Yee, I. (1993). Effects of search experience and

subject knowledge on the search tactics of novice and experienced searchers. Journal of the American Society for

Information Science, 44(3), 161-174. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1097-4571(199304)44:3<161::AID-ASI5>3.0.CO;2-8

Institute of Medicine. (2011). Finding what works in health care : Standards for systematic reviews.

Washington DC: National Academies PressRetrieved from www.nap.edu/openbook.php?record_id=13059

Kuhlthau, C. C. (1999). The role of experience in the

information search process of an early career information worker: Perceptions

of uncertainty, complexity, construction, and sources. Journal of the American Society for Information Science, 50(5),

399-412. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/(Sici)1097-4571(1999)50:5<399::Aid-Asi3>3.0.Co;2-L

Reed, D. A., Cook, D. A., Beckman, T. J., Levine, R.

B., Kern, D. E., & Wright, S. M. (2007). Association between funding and

quality of published medical education research. Journal of the American Medical Association, 298(9), 1002-1009.

doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/jama.298.9.1002

Savoie, I., Helmer, D., Green, C. J., & Kazanjian,

A. (2003). Beyond Medline: Reducing bias through extended systematic review

search. International Journal of

Technology Assessment in Health Care, 19(1), 168-178. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0266462303000163

Tabatabai, D., & Shore, B. M. (2005). How experts

and novices search the Web. Library &

Information Science Research, 27(2), 222-248. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.lisr.2005.01.005

Wright, J. M., Cottrell, D. J., & Mir, G. (2014). Searching for

religion and mental health studies required health, social science, and grey

literature databases. Journal of Clinical

Epidemiology, 67(7), 800-810. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2014.02.017

Appendix

Survey -Part One

CONTACT INFORMATION - solely used for communication

with you regarding the study

First Name

Last Name

Institution/Organization

E-mail

Phone

INFORMATION ABOUT THE SEARCHER

1.

Country of Employment

2.

List Academic Credentials (e.g., PhD, MLIS, MPH)

3.

Type of Institution

·

Academic

·

Hospital

·

Industry/Corporation

·

Government Agency

·

Organization/Agency (non-Government)

·

Other (If Other, specify)

4.

Position Title

5.

Select an option which represents your primary

professional role

- Librarian/Information

Professional

- Researcher

- Healthcare

Professional

- Statistician

- Student

- Other

(If Other, specify)

6.

Years of experience in your profession (that you

selected in Question 5)?

7. Have you had any formal training on how to

conduct literature searching

for Systematic Reviews? YES/NO

8.

Approximately how many years of experience do you have

contributing to Systematic Reviews?

9.

Approximately how many Systematic Reviews have you

contributed to in the past?

Survey -Part Two

INFORMATION ABOUT THE SYSTEMATIC REVIEW (SR)

1.

Please list the title or the topic of the SR.

Note- This

information will only be used to classify the SRs into subject categories.

2.

Please select the population age group included in the

SR.

- Adults

- Pediatrics

- Both

3.

Which category best describes the type of Systematic

Review?

- Therapy

- Diagnosis

- Prognosis

- Etiology

- Adverse

Effects

- Methodology

- Other

- Not

Sure

4.

Is this SR grant funded? YES/NO

5.

Is this SR being produced under the guidance of a

systematic review funding or producing agency/organization? YES/NO/NOT SURE

6.

Should the SR be published, are there plans for you to

be a coauthor? YES/NO/NOT SURE

7.

If you are NOT a librarian/information professional,

is there one involved in the SR?

If you are a

librarian/information professional select N/A

YES/NO/ N/A

If YES, in

what primary role?

- Manage

project

- Overall

search responsibility

- Assist

with search strategy design

- Suggest

resources

- Provide

general guidance

- Assist

with full text acquisition

- Other

INFORMATION ABOUT SEARCHING FOR THE SYSTEMATIC REVIEW

(SR)

8.

Is cited reference searching (checking who cited a

paper) or checking the reference lists of papers of interest, planned as part

of the search effort for this SR?

- Cited

reference searching

- Checking

reference lists

- Both

- None

9.

Will a methodology filter be used in the SR search? (A

methodology filter is a pre-designed search strategy with terms related to

research methodology. Examples include the Cochrane Highly Sensitive Search

Strategy and Clinical Queries.) YES/NO

If YES, for

which resources?

10.

Were any resources purchased

as a one-time paid subscription for purposes of a search for the SR? YES/NO

11.

May we contact you to ask

for the final number of studies included and where the citations were

originally found? YES/NO

12.

Use the following table to

document all resources searched for the SR.

If any journals or conference proceedings were

handsearched, label with Handsearch followed

by a dash and the Title of the Resource in the RESOURCE NAME column. Indicate

in RESOURCE Platform column whether the print or electronic version was

handsearched

If a resource was purchased as a one-time paid subscription

for purposes of a search for this SR, please mark with an asterisk (*) preceding the resource name in the

RESOURCE NAME column.

Use n/a if

an item does not apply, to indicate that you are unable to identify the

information, or if the information is not available

Three examples are provided, although the time is not

documented

|

ANOTHER1 |

DATE SEARCHED |

RESOURCE NAME |

RESOURCE Platform/ Interface/ Vendor |

RESOURCE URL |

TIME in minutes2 |

|

|

1/22/2010 |

* BIOSIS Previews |

Dialog |

n/a |

Insert Time Here |

|

|

2/10/2010 |

clinicaltrials.gov |

n/a |

clinicaltrials.gov |

Insert Time Here |

|

x |

1/4/2010- 3/1/2010 |

Handsearch- Proceedings of the Nutritional Society (2007-2009) |

print |

n/a |

Insert Time Here |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1 Mark with an

X resources you did not search yourself but that were searched for the SR

2 Time should

account for choosing terminology, developing the strategy, and running the

search