Article

Looking and Listening: A Mixed-Methods Study of Space

Use and User Satisfaction

Sara Holder

Head Librarian

Schulich Library (Science,

Engineering & Medicine)

McGill University

Montreal, Canada

Email: sara.holder@mcgill.ca

Jessica Lange

Business Librarian

Humanities & Social Sciences Library

McGill University

Montreal, Canada

Email: jessica.lange@mcgill.ca

Received: 4 June 2014 Accepted: 7

Aug. 2014

![]() 2014 Holder and Lange. This is an

Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

2014 Holder and Lange. This is an

Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

Abstract

Objective

– This

study was designed to assess users' reactions to two newly re-designed spaces –

one intended for quiet study and the other for group study – in the busiest

library branch of a large research university. The researchers sought to answer

the following questions: For which activity (group work, quiet study, and

lounging or relaxing) do the users feel the space is most effective? Which

furniture pieces do users prefer and for which activities? How are these spaces

being used?

Methods

– Researchers

used a mixed-methods approach for this study. Two methods – surveys and comment

boards – were used to gather user feedback on preference for use of the space

and users’ feelings about particular furniture types. A third method –

observation – was used to determine which of the particular areas and furniture

pieces occupants were using most, for which activities the furniture was most

commonly used, and what types of possessions occupants most often carried with

them.

Results

– User

opinion indicated that each of the spaces assessed was most effective for the type

of activity for which it was designed. Of the 80% of respondents that indicated

they would use the quiet study space for quiet study, 91% indicated that the

space was either "very effective" or "effective" for that

purpose. The survey results also indicated that 47% of the respondents would

use the group study space for that purpose. The observation data confirmed that

the quiet study space was being used primarily for individual study; however,

the data for the group study space showed equal levels of use for individual

and group study. Users expressed a preference for traditional furniture, such

as tables and desk chairs, over comfortable pieces for group work and for quiet

study. One exception was a cushioned reading chair that was the preferred item

for quiet study in 23% of the responses. The white boards were chosen as a

preferred item for group study by 27% of respondents. The observations showed

similar results for group study, with the three table types and the desk chair

being used most often. The lounge chairs and couch grouping was used most often

for individual study, followed by the tables and desk chairs.

Conclusion

– By

combining user feedback gathered through surveys and comment boards with usage

patterns determined via observation data, the researchers were able to answer

the questions for which their assessment was designed. Results were analyzed to

compare user-stated preferences with actual behaviour and were used to make

future design decisions for other library spaces. Although the results of this

study are institutionally specific, the methodology could be successfully applied

in other library settings.

Introduction

Library spaces are increasingly transforming from

those designed to house collections to those concerned with user comfort and

support for activities beyond the use of the collection. When planning these

user-centered spaces, it is common practice to assess the preferences and needs

of the users who will ultimately occupy them. Some libraries have gathered user

feedback both pre-design and post-design, prior to construction or renovation

(Norton, Butson, Tennant, & Botero, 2013). But what of the users’ opinions

of these new or updated spaces once they are completed? Is it necessary to

gather these opinions? An argument could be made that it is not essential if

the designers of the space have been conscientious in polling users and

applying their feedback. Feedback could also be risky in a situation where it

would be difficult to change elements of the design should the user feedback be

negative. What if, however, there were opportunities to duplicate the design,

or use elements of it, in other spaces? This consideration was at the root of

the project described in this article.

The Humanities & Social Sciences Library at McGill

University is comprised of two adjoining structures, the McLennan and Redpath

library buildings (known in combination as the McLennan-Redpath Complex). The

public spaces in these buildings have been updated at various times throughout

their lifespans; however, there had not been any targeted efforts to determine

whether the spaces were meeting students' needs. The first project was to assess

a recently renovated quiet study area on the third floor of the McLennan

Building. Upgrades included new lighting and furniture: specifically, long,

electrified tables with dividers, large and small tables on wheels, simple desk

chairs, and comfortable reading chairs.

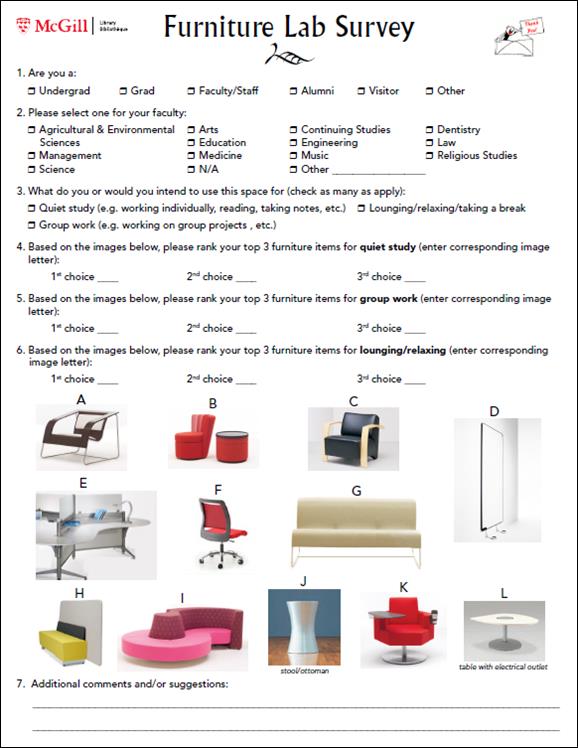

The second project involved a deal with a local

company to provide furniture pieces on a trial basis that the library could

either purchase or switch out for different types. The trial furniture was

largely of the comfortable seating type but also included two configurations of

tables and desk chairs as well as moveable and fixed white boards. In order to

showcase these pieces, the library opened up an area of recently vacated staff

space to create a large group work zone (including two enclosed, bookable group

study rooms), dubbed the “furniture lab.” With these two projects in place, the

library administration tasked the McLennan-Redpath Space Planning Working Group

with gathering student feedback. Given the large number of new furniture types

and pieces being used in these spaces, and the trade-in agreement for the

furniture lab pieces, the administration was particularly interested in gauging

student reaction to the individual types and pieces and finding out how the

students were using the furniture and the spaces. If these spaces were

well-received by users, they could be duplicated, either in whole or in part,

in other areas of the complex and in other branches. The nature of these

renovations also left some latitude for change if users were not satisfied.

Literature Review

In the past decade there

has been an increasing body of library research devoted to space planning and

space assessment in libraries. As Webb,

Schaller, and Hunley (2008) note, “the proliferation of digital formats,

the options for high density storage, and the increased ease of resource

sharing have reduced the need for on-site collection storage thus opening up

space for other types of services” (p. 407). “Library as place” has emerged as

librarians look for ways to accurately measure how users are engaging with

their spaces, what users want from their spaces, and what the space demands

will be for the future. Future space demands are particularly hard to predict,

especially with changing technology. For example, increasing the number of

electrical outlets has been identified as a major space need in many studies

given the rise of the laptop computer, something that may have been difficult

to imagine even 10 or 15 years ago

(Brown-Sica, 2012; Halling & Carrigan, 2012;

Norton et al., 2013; Vaska, Chan, & Powelson, 2009).

In the space planning literature,

obtaining information on user preferences and space demands is addressed in

various ways. One common method is to engage students directly about their

desires for changes to library spaces. Many studies rely on traditional

feedback methodologies such as surveys, focus groups, whiteboards, and comment

boards to obtain information; however, more innovative

strategies such as photo diaries and mediated drawing exercises are also being

explored. For example, Crook and Mitchell (2012)

had several of their students keep an audio diary to reflect on their study

habits and behaviour. Similarly, Hobbs and Klare

(2010) provided students with disposable cameras and asked them to

photograph their interpretation of various pre-defined subjects such as their

favourite place to study. Other studies focus on what students actually do in library spaces; these studies rely

on observational methods to ascertain how users are engaging with their spaces.

Bedwell and Banks (2013) partnered with

an anthropology class at their university to make direct observations of

students’ habits, activities, and behaviours in the library. Others have

employed a mixed methodology, using several of these approaches to answer their

research questions. For example, Pierard and Lee

(2011) employed photo diaries, flipcharts, and a traditional user survey

in their study, and Crook and Mitchell (2012) employed observation, audio

diaries, and focus groups, while Foster and Gibbons (2007) used interviews,

maps, photographs, and flipcharts. These less traditional means for obtaining

feedback are considered ethnographic approaches. As Asher, Miller, and

Green (2012) write, “ethnographers typically describe a

particular situation or process by asking multiple people about it, and by

analyzing multiple types of data, such as interviews, direct observation,

photographs, journals, or cultural artifacts” (p. 3). Through combining various

feedback methodologies, researchers hope to obtain more well-rounded and

comprehensive information about the population which they are studying.

Beyond library

literature, the fields of urban planning and architecture provide insights into

further feedback methodologies for public spaces. In addition to interviews and

observation methods, Doxtater (2005) employed an online virtual recreation of a

university residence to understand user experiences with the space. Hua, Göçer, and Göçer (2014) used interviews and surveys to understand

user satisfaction with a newly LEED (Leadership in Environmental Energy and

Design) certified university building. This data was then combined with

objective measurements such as temperature and humidity and mapped spatially to

create a visual representation of how effective the renovations had been.

Within architecture literature, post-occupancy evaluations provide additional

examples of obtaining user feedback about spaces. The San Francisco Public

Library (2000) administered focus groups, staff and user surveys, observations,

and interviews to evaluate library spaces. In her article, Cranz (2013)

outlines the effects of this post-occupancy evaluation on the San Francisco Public

Library. Preiser and Wang (2008) provide an additional example of a

post-occupancy evaluation of a library space by architects.

Likewise, literature on

urban planning involving citizen participation can also provide additional

feedback approaches. Shipley and Utz (2012) provide a good overview of these

methods, such as public meetings, focus groups, citizen juries, visioning, and

scenario workshops.

One component discussed

in several space planning research articles is furniture preference: do students

prefer couches, carrels, booths, or other types of furniture? Research

conducted by Halling and Carrigan (2012),

Hobbs and Klare (2010), Pierard and Lee (2011), and Webb et al. (2008) identified a preference or desire

for soft or comfortable furniture. While most of the aforementioned studies

relied on student comments or surveys to determine this preference, Webb et al. (2008) supported this through

direct observation as well.

They found there was a “higher than expected usage for soft furniture and

computer stations” and a lower than expected usage for more traditional types

of furniture such as large tables and chairs (Webb

et al., 2008, p. 415). Foster and Gibbons (2007) came to this same

conclusion. However, the preference for “soft” or comfortable is not consistent

across all studies and there is often a difference between students’ stated

preference and their behaviour.

Contrary to the above, Vaska et al. (2009) discovered in their survey that carrel areas in the

library were the most popular spaces, while Applegate

(2009) noted through observation that study rooms were the most

frequently used spaces (followed by “soft spaces”). Brown-Sica (2012) also noted through observation that traditional

furniture such as tables and chairs were popular, reflecting a “need to ‘get

down to work’ as opposed to socializing” (p. 223). This contrast in findings

may best be explained by the diversity of functions that students wish their

library to fulfill. Bailin (2011) found

that students wanted more of everything out of their library space (more

individual study spaces, more group study spaces, more computers) and that the

breakdown of what spaces students said they used is fairly evenly divided

across all options (e.g., group, individual, lounge, and others). Webb et al. (2008) noted through observation

that 70% of the students were engaged in individual study (p. 416). Crook and Mitchell (2012) observed that

approximately 50% of students were engaged in individual study while the rest

were engaged in conversation of some variety (p. 128). This diversity of

activities in libraries may best be summed up by Montgomery (2011), who ascertained that students “want to study

alone but still need space to meet in groups” (p. 84). As such, a variety of

furniture is required in order to meet those needs.

Based on the literature consulted,

initial student feedback, and general observations, the Working Group had

several assumptions about what the study would find. Given the ubiquity of

laptops as well as the literature reviewed, they anticipated that students

would desire more outlets. Additionally, even though the Humanities &

Social Sciences Library is intended primarily for students in the Faculty of

Arts, given the central location and size of the branch, the group anticipated

that students from all disciplines would make use of the space. With regards to

the furniture lab, they hypothesized that it would be used primarily for group

study, as it is located in a high traffic area. Finally, given several studies

which outlined student preference for furniture, and some initial student

feedback they had received, the Working Group expected that students would

prefer “comfy” or “soft” furniture in the furniture lab space. However, since

this study was partly exploratory, the group hoped to obtain additional

information beyond the assumptions outlined.

Methodology

The Working Group chose to use a combination of

methods to obtain data about these spaces: surveys, observation, and comment

boards. They designed a survey instrument with questions that focused on

elements that could be changed (such as furniture) and questions that prompted

the respondents to offer their opinion of what type of activities the space was

best suited for. Similarly, they used the comment boards to solicit feedback on

particular furniture pieces and general satisfaction with the spaces. To

account for the potential difference in students’ stated preferences and their

actual behaviour, the researchers also employed the observation method

(Goodman, 2011). Using survey and observation methods together provided a more

complete picture of user satisfaction with the spaces, as well as user preference

for particular areas and furniture types. This mixed-methodology approach and

combination of survey and observation data was inspired by Webb et al. (2008),

who combined video surveillance footage with surveys and web polls to obtain

information on students’ library space use.

Although Webb et

al. (2008) inspired this mixed methodology approach, due to privacy

regulations, video surveillance was not an option for observing student

behavior at McGill. For this reason, the Working Group modeled their

observation method on Given and Leckie (2003), who describe how research teams

at two Canadian public libraries used “an unobtrusive patron-observation

survey, called ‘seating sweeps’” to answer questions about the use and

functionality of central libraries as public space (p. 373). This observation

method collects minimal user demographics (sex, estimated age) and data on user

activity (what they are doing) and possessions (what they have with them) in a

specified space at a specified time. The observation criteria used was also

adapted from Given and Leckie

(2003), particularly their list of possessions and activities. This method also

allowed the group to compare the students’ survey responses and comments with

their behaviour. Since there were two separate spaces being evaluated, all of

the data collection elements had two parts – one for the furniture lab and one

for the McLennan Building third floor space.

The Working

Group's use of comment boards had its roots in two places. Several members of the

group had prior experience with this method and had found that it complimented

the use of surveys. Use of this approach was also inspired by Halling and

Carrigan (2012) who utilized whiteboard voting in their study as one method for

obtaining student feedback.

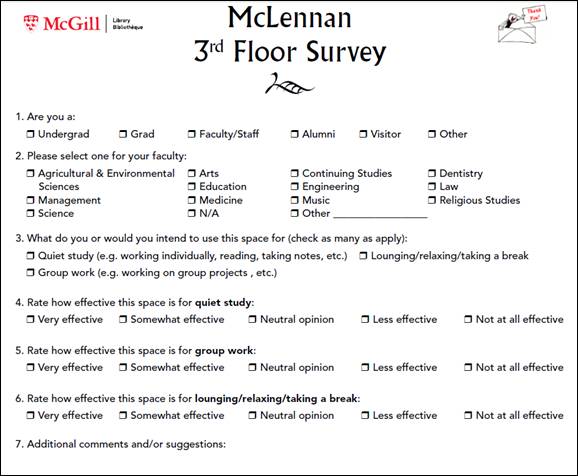

Survey Design

Both the McLennan

Building third floor survey (Appendix A) and the furniture lab survey (Appendix

B) instruments included seven questions: six multiple choice and one

open-ended. Two of the questions were demographic (type of patron and

faculty/department affiliation) and four were designed to obtain the students’

opinions about the effectiveness of the space and furniture pieces for

particular activities (group work, quiet study, and lounging or relaxing). On

both surveys, the final question was open-ended to allow for any additional

comments or suggestions regarding the space or furniture. All of the questions

on both surveys were optional and the surveys were completely anonymous.

Data Collection

Surveys

Both of the

surveys were made available in paper and online format. The paper surveys were

offered to students using a container attached to the boards through which

comments were being solicited. A second container was used to collect the

completed surveys. The group members also used these boards to indicate the web

address where students could access the online version of the surveys, which

were offered via SurveyMonkey. Both versions of the surveys were available for

approximately two weeks.

Comment boards

In order to

solicit comments on the boards, group members used a combination of open

questions about the space and about specific pieces of furniture. Using the

bulletin boards, the group members attached pictures of specific pieces of

furniture spaced evenly throughout the board with the following solicitation

across the top of the board: “We want to know what you think of the new group

study space.” Additional prompts were posted as well, such as: “Which is your

favorite?” and “love it/love it not.” Sticky notes and markers were available

so students could write comments and attach them near the relevant furniture

picture. The group members used the whiteboards to solicit comments about the

space by writing: “What do you think of this space?” or simply: “Comments?”

Group members visited the boards several times each day to collect the

completed surveys and to take pictures of (and refresh) the comment boards.

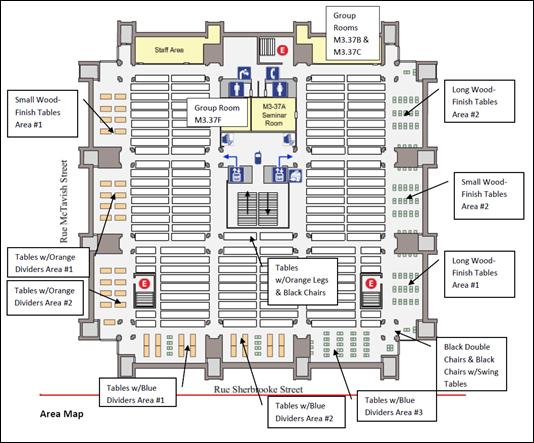

Observation

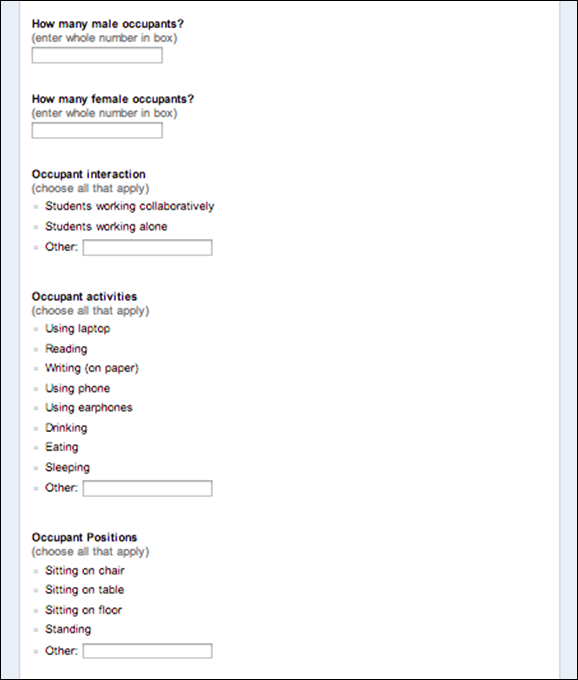

The group members

set up two online forms (one for each space) using Google Drive to record and

analyze the data from their observations. This gave the observers the choice of

recording their observations on paper and entering the results in the online

form at their leisure or using a laptop or tablet to record the data in the

online form as they performed their observations. The observation forms

(Appendix C) were designed using Given and Leckie's (2003) as a template. The

group members decided to record the number of male and female users but not to

estimate the users’ age as this was not relevant to the study. They used some

of the same variables as Given and Leckie (2003) in the possessions and

activities categories and made some additions. They also added four categories

to the form: interaction (students working alone/students working collaboratively/other),

position (sitting/standing/other), whiteboard use (no whiteboard/not

using/using individually/using interactively/there is writing on whiteboard but

not clear if it is from current occupant/other), and adequate space provided

for possessions (yes/no/other).

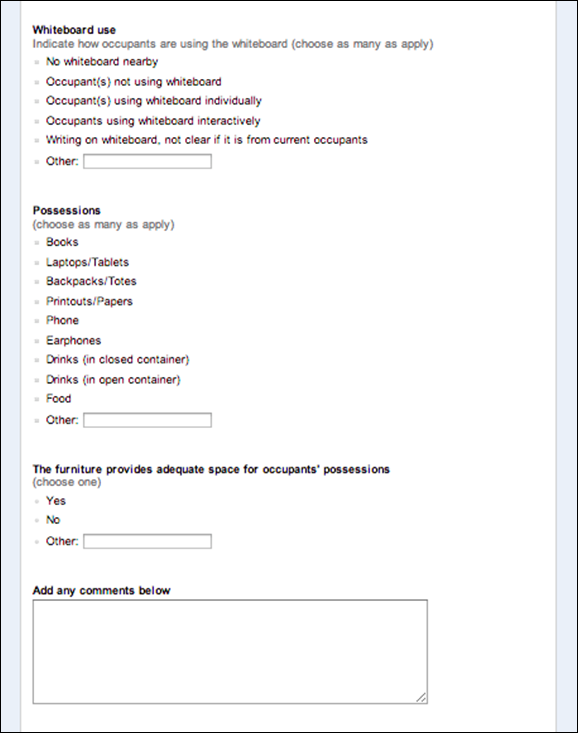

The group members

mapped out both spaces in order to break them down into locations that would be

observed. The McLennan Building third floor space includes several different

types of seating in repeated groupings throughout the floor (Appendix D: Third

Floor Area Map). The group members assigned numbers to each of these similar

seating groups (e.g., tables with blue dividers, area #1, #2, etc.), as well as

the four group study/seminar rooms, and added them as locations. A total of 14

locations were included in the observation form for the McLennan Building third

floor space. The form for the furniture lab space also included 14 locations;

however, on this form each of the locations corresponded to individual

furniture types (Appendix E: Furniture Lab Pictures). The group members planned

12 observations of each space at corresponding times spread over one week

(Table 1). In total, 10 observations were completed for the furniture lab space

and 11 for the McLennan Building third floor space.

Results

Surveys

Third

floor

The Working Group received 41 completed surveys (38

paper and 3 online) for the McLennan Building third floor space and 88 (78

paper and 10 online) for the furniture lab space. The respondents to both

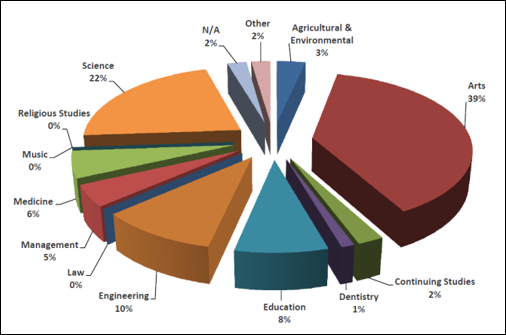

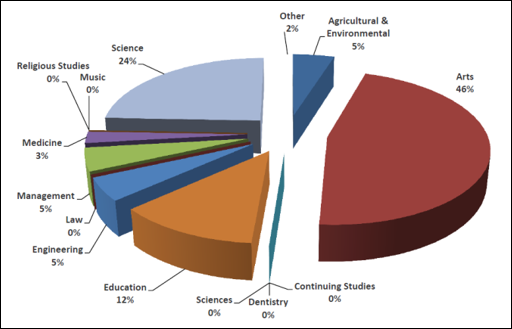

surveys were primarily undergraduates (85% and 90%) and the largest number

indicated that they were part of the Faculty of Arts (39% and 46%). This was

not surprising as the Humanities & Social Sciences Library houses many of

the materials the Arts students would need to complete their assignments, as well

as the offices of the liaison librarians for the departments in the Faculty.

However, it was notable that the second largest number of respondents to both

surveys indicated they were part of the Faculty of Science (24% and 22%). Most

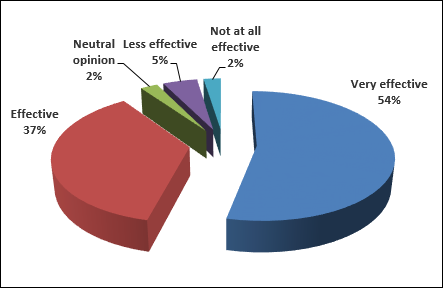

respondents (77%) to the McLennan Building third floor space survey indicated

that they use the space for quiet study, and 91% rated the space either very

effective (54%) or somewhat effective (37%) for this type of studying (Figure

1).

The comments regarding the McLennan Building third

floor space design were very positive, in particular regarding the lighting,

colour scheme, and designation of zones for quiet study. Several respondents

suggested that the space could be improved if more electrical outlets were

added and several others suggested that library staff should enforce the quiet

study concept for those zones. Temperature is often an issue in the large

buildings on the McGill campus (especially in the winter) so it was not a

surprise that numerous respondents mentioned that the space was too cold.

Furniture

Lab

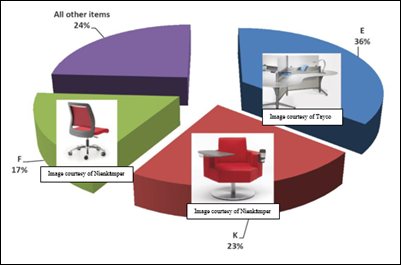

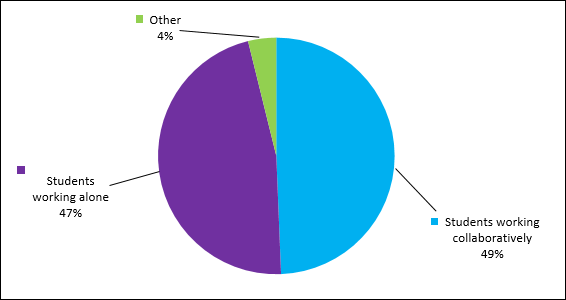

The responses for space use preference in the

furniture lab were more surprising, considering that the space was designed for

group work. The largest group of responses (47%) indicated the intent to use

the space for group work; however, 30% of respondents indicated that they

intended to use the space for quiet study, and 23% indicated that they intended

to use the space for lounging or relaxing (Figure 2).

Table 1

Observation Times for Furniture Lab and McLennan

Building Third Floor Space

(Week of December 9, 2012)

|

Day |

Time |

|

Monday |

10 a.m. |

|

Tuesday |

10 a.m., 2 p.m., 4 p.m. |

|

Thursday |

10 a.m., 2 p.m., 4 p.m. |

|

Friday |

10 a.m., 2 p.m., 4 p.m. |

|

Saturday |

5 p.m. |

|

Sunday |

8 p.m. |

Figure 1

Effectiveness of the third floor study space for quiet

or individual study.

Figure 2

Preference for space use, furniture lab.

The survey form (Appendix B) offered a selection of 12

furniture pieces so that respondents could indicate their top preference for

the three types of activity: group study, quiet study, and lounging or

relaxing. For quiet study, 36% of respondents chose the Y-shaped divided table

as the top furniture item, with the red desk-arm chair a close second at 23%.

The other highly-rated item was the desk chair (17%), which is used with the

Y-shaped divided table and the U-shaped table (Figure 3). The top-rated item

for group work was the portable whiteboard (27%), followed by the desk chair

(13%) and the U-shaped table (11%) (Figure 4). The remaining 49% of the

responses for this question were divided among the other nine furniture items.

Figure 3

Furniture preference, quiet study.

Figure 4

Furniture preference, group study.

There was a similar breakdown in responses for the

top-rated item for lounging or relaxing. The question mark lounger was chosen

by 23% of respondents, the reading chair with wooden arms by 20%, and the

low-slung reading chair by 17%. The remaining 40% of responses were divided

among the remaining nine items. The final question on both survey forms was an

open-ended solicitation for comments or suggestions. The furniture lab survey

respondents most commonly suggested that the space should have more tables,

electrical outlets, and whiteboards. They also suggested that the whiteboard

markers be replaced more frequently. The comments were generally positive

toward the space, especially its design and designation as a group study space,

though there was a mixed response to the furniture colours.

Comment Boards

The bulletin board and whiteboard comments were a mix

of positive and negative; however, several items received consistently positive

comments. These items included the moveable whiteboards ("more

please"), the round and U-shaped tables and desk chairs ("the

best"; "beautiful"), the low-slung reading chair ("this

chair is pure happiness"), and the question mark lounger ("love it -

so sassy"). It was notable that the three-sided table that had been the

top choice in the furniture lab survey for quiet study received comments that

confirmed it was not well-suited for group work ("chairs too close to each

other"; "more appropriate for individual study space").

Observation

Third

floor

During the 11 observations completed for the McLennan

Building third floor space, the Working Group members observed a total of 1,565

occupants. With the exception of two of the group study rooms, observations of

each area showed a much higher instance (80% or greater) of occupants working

alone than working together. In the areas where a whiteboard was present, all

observations showed it was either being used or had been used (i.e., there was

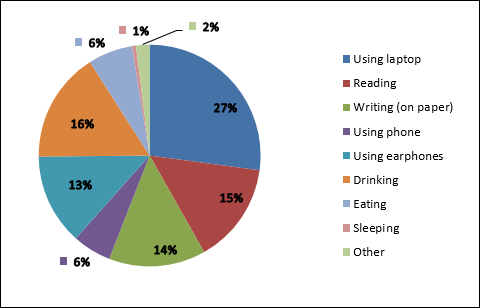

writing on it). The occupants in the third floor space were most commonly

observed carrying out the following activities: using laptops or tablets,

reading, writing, and using earphones (Figure 5). The most common possessions

observed were laptops or tablets, books, paper, backpacks or totes, and

earphones. Many of the occupants were observed in possession of beverages and

most often (>60% of the time) these were in closed containers. Eating was

observed infrequently (<20% of the time).

Furniture

Lab

In the 10 observations completed for the furniture lab

space, a total of 490 occupants were observed. Though the space was designed

for group study, observations showed occupants using the space equally for

independent study and for collaborative work. Collaborative work was observed

most often in the group study rooms, at the Y-shaped divided table, and at the

U-shaped and round tables. The whiteboards paired with the U-shaped tables were

in use most often, followed closely by the whiteboards in the group study

rooms. The main activities taking place in the furniture lab space were

virtually the same as those most commonly observed in the McLennan Building

third floor space; however, drinking was slightly more common than using

earphones (16% vs. 13%). Eating was indicated in approximately 18% of the

observations, most commonly at the round and U-shaped tables. Occupants at the

round tables, the U-shaped tables, and on the rounded chairs were most often

observed reading. The most common possessions observed were identical to the

McLennan Building third floor space. Occupants in the furniture lab space were

in possession of drinks (most often in closed containers) on average 35% of the

time.

Figure 5

Occupant activities, third floor.

Figure 6

Occupant activities, furniture lab.

Discussion

Two

of the Working Group's initial assumptions proved to be accurate: that students

would desire more outlets and that students from all disciplines would make use

of the space.

It was not surprising, given the consensus in the

literature that one of the students’ most frequent suggestions was for

additional electrical outlets (Brown-Sica, 2012; Halling & Carrigan, 2012;

Norton et al., 2013; Vaska et al., 2009). This was doubly confirmed via the

observations, during which it was noted that both in the third floor quiet

space and in the furniture lab, the most commonly observed item in the

occupants’ possession was a laptop or tablet. These results, together with the

studies mentioned earlier, provide evidence for including ample access to

electricity in the design of any library space.

In reviewing the results from the surveys and comment

boards, some were as expected, particularly the use of the spaces by students

from a wide range of disciplines. Even though the McLennan-Redpath Library

complex serves primarily students in the Faculty of Arts, its location at the

centre of campus makes it a hub for students in all faculties. This was

demonstrated in the survey responses showing that all faculties were

represented; notably, students in the Faculty of Science made up almost one

quarter of those surveyed (Figures 7 and 8).

Two of Working Group's other assumptions proved to be

inaccurate: that students would prefer “comfy” or “soft” furniture and that the

furniture lab would be used primarily for group study.

Both the survey responses and observations revealed a

desire among users for more traditional furniture such as tables and desk

chairs. The observation data showed that tables were the most commonly used

item in the furniture lab for group study and that the lounge chair and couch

grouping was only slightly more commonly used than the tables for individual

study. In the surveys, the tables, desk chairs, and moveable whiteboards were

the most preferred items. One cushioned reading chair was the only

"comfy" item to show as preferred (23% for quiet study). As libraries

are more and more becoming a “home away from home” for students, the Working

Group members had anticipated users would express a greater preference for

“comfy” furniture. There is also considerable evidence for this furniture type

preference in the literature (Halling & Carrigan, 2012; Hobbs & Klare,

2010; Montgomery, 2011; Pierard & Lee, 2011; Webb et al., 2008). This

divergence from the existing body of evidence indicates potential for further

investigation; however, it may be attributable to the difference in survey

design. The furniture lab survey instrument (Appendix B) provided the

opportunity for users to rate furniture based on its intended use (i.e.,

individual study, group study, or relaxing). Other furniture preference studies

asked more generally what type of furniture students would prefer without

providing the option for selecting furniture based on different use scenarios.

Additionally, given that this study dealt with particular furniture pieces, it

is possible that the respondents and occupants choices may indicate a lack of

truly comfortable options rather than a true preference for desks and tables.

Foster and Gibbons (2007) discuss in their chapter on

library design and ethnography that in their experience, library “zones” are

“neither determined nor enforced by the library staff. Rather the students

develop and enforce them” (p. 20). Given that assessment, the researchers

should not have been surprised to discover that the furniture lab space was not

being used as they had initially intended. The furniture lab is located in a

busy, high-traffic area of the library; however, almost one-third of survey

respondents indicated that they used the furniture lab for individual or quiet

study. This was also confirmed through the observation results (Figure 9) that show

occupants working collaboratively just under 50% of the time.

Figure 7

Survey respondents by faculty, furniture lab.

Figure 8

Survey respondents by faculty, third floor.

Several other studies have found similar results

(Bryant, Matthews, & Walton, 2009; Crook & Mitchell, 2012; Harrop &

Turpin, 2013), which suggests this could be a common pattern in the use of

space designed for group work. It would require further analysis to determine

if students were willingly choosing to do their quiet study in that area or if

this was not so much a choice as a necessity, given the lack of sufficient

quiet space elsewhere in the library.

Beyond validating or contradicting initial

assumptions, the multi-method approach allowed the Working Group to discover

additional information. In both the furniture lab and the third floor quiet

space, the most commonly observed activities were the same: using laptops or

tablets, reading, writing, and using earphones. This is consistent with other

studies utilizing the observation method. Given and Leckie's (2003) results,

gathered over ten years ago when laptops were less prevalent, found that

reading and writing were the most popular activities, followed by computer use.

Bryant et al. (2009) found similar results, as did Lehto, Toivonen, and Iivonen

(2012).

However, it was encouraging to learn both through

observation and through survey analysis that the third floor space was being

used for its intended purpose (i.e., quiet study) and that it was generally

regarded to be effective in fulfilling that objective.

Limitations

In embarking on this project, the Working Group

members’ objective was to get a better sense of what users liked and did not

like about the re-designed spaces and how they were using the spaces. With this

in mind, the group did not set out to be exhaustive in their data collection;

they focused instead on using several methods to gather sufficient data to

answer their questions without overextending staff time or annoying users. This

approach limits the analysis and the strength of the conclusions that can be drawn

from the data. The library is open to the public and the survey and comment

boards were made freely available, thus the population size is unknown and the

response rate cannot be defined. For this same reason there was no way to

control for duplication or multiple

responses from the same individual. The results from the observations do not

provide a complete picture, as data was not collected during the late night or

early morning hours. Finally, as is the case with any study done in a single

site involving a particular population, the results of this investigation

cannot be assumed to be typical or indicative of the opinions and preferences

of other university populations. However, the authors feel that the methods

could be successfully applied in other library settings.

Figure 9

Observed occupant interaction, furniture lab.

Conclusion

As library spaces continue to adapt to meet the

changing needs and expectations of their users, it is important for library

administrators to gather feedback on user preferences and usage patterns. The

past twenty years have seen radical changes in the physical layouts and use of

space in libraries and there is no doubt that library spaces will continue to

adapt and evolve over the course of the next several decades.

The authors found that a mixed method analysis was

particularly useful for this project to determine both what users want out of

their library spaces and how they are currently using them. Observation data

demonstrated usage patterns that may have been overlooked by traditional survey

methods. Conversely, survey responses provided important user feedback and

comments. By combining the methods, this study illuminates some key issues,

notably, the desire for traditional furniture (tables, chairs), as well as the

need for more electrical outlets in all areas of the library, and the positive

return on investment (high incidence of usage and user satisfaction) for the

relatively low-cost addition of whiteboards. It also confirms that some library

spaces are satisfying their anticipated need: the third floor quiet study area

is in fact being used for that purpose and a majority of respondents find it

effective in that respect.

The results of this project have been used to inform

purchasing decisions to outfit other spaces in the McLennan-Redpath Complex as

well as in other libraries on campus. The furniture lab space is being expanded

such that it will more than double in size. Following the findings of this

study that the space was used for both group and individual work, the expanded

space has been laid out accordingly and filled with the furniture items

identified as most popular for each type of work. The most popular items from

the furniture lab have also been installed in another branch’s new group space,

and whiteboards have been added in several branches. The positive student

response to the third floor space has been a factor in renovation design

decisions for the first and second floors of the McLennan Library Building. The

furniture in both areas has been updated to include long wood-finish tables

(some with dividers, some without), similar to the ones observed to be popular

in this study. All re-designed spaces and new tables will have multiple power

outlets per seat (plug and USB). Going forward, the library plans to continue

obtaining user feedback to inform space planning decisions and to adapt the

results of the research undertaken here to other library spaces on campus.

References

Applegate,

R. (2009). The library is for studying: Student preferences for study space. The Journal of Academic Librarianship, 35(4),

341-346. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2009.04.004

Asher,

A. D., Miller, S., & Green, D. (2012). Ethnographic research in Illinois

academic libraries: The ERIAL Project. In L. M. Duke, & A. D. Asher (Eds.),

College libraries and student culture:

What we now know (pp. 1-14). Chicago, IL: American Library Association.

Bailin,

K. (2011). Changes in academic library space: A case study at the University of

New South Wales. Australian Academic

& Research Libraries, 42(4),

342-359. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00048623.2011.10722245

Bedwell,

L., & Banks, C. (2013). Seeing through the eyes of students: Participant

observation in an academic library. Partnership:

The Canadian Journal of Library & Information Practice & Research, 8(1),

1-17. Retrieved from http://condor.lib.uoguelph.ca/index.php/perj/article/view/2502/2905

Brown-Sica,

M. S. (2012). Library spaces for urban, diverse commuter students: A

participatory action research project. College

& Research Libraries, 73(3), 217-231. Retrieved from http://crl.acrl.org/content/73/3/217.full.pdf

Bryant,

J., Matthews, G., & Walton, G. (2009). Academic libraries and social and

learning space: A case study of Loughborough University Library, UK. Journal of Librarianship and Information

Science, 41(1), 7-18. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0961000608099895

Cranz,

G. (2013). How post-occupancy evaluation research affected design and policy at

the San Francisco Public Library. Journal of Architectural & Planning

Research, 30(1), 77-90.

Crook,

C., & Mitchell, G. (2012). Ambience in social learning: Student engagement

with new designs for learning spaces. Cambridge

Journal of Education, 42(2), 121-139. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/0305764X.2012.676627

Doxtater,

D. (2005). Living in La Paz: An ethnographic evaluation of categories of

experience in a 'new urban' residence hall. Journal of Architectural &

Planning Research, 22(1), 30-50.

Foster, N. F., &

Gibbons, S. (2007). Studying

students: The undergraduate research project at the University of Rochester.

Chicago, IL: Association of College and Research Libraries.

Given,

L. M., & Leckie, G. J. (2003). ‘‘Sweeping’’ the library: Mapping the social

activity space of the public library. Library

& Information Science Research, 25(3), 365–385. http://dx.doi.org/doi:10.1016/S0740-8188(03)00049-5

Goodman,

V. D. (2011). Qualitative research and

the modern library. Oxford, England: Chandos.

Halling,

T. D., & Carrigan, E. (2012). Navigating user feedback channels to chart an

evidence based course for library redesign. Evidence

Based Library & Information Practice, 7(1), 70-81. Retrieved from http://ejournals.library.ualberta.ca/index.php/EBLIP/article/view/10207

Harrop,

D., & Turpin, B., (2013). A study exploring learners' informal learning

space behaviors, attitudes, and preferences. New Review of Academic Librarianship, 19(1), 58-77. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13614533.2013.740961

Hobbs,

K., & Klare, D. (2010). User driven design: Using ethnographic techniques to

plan student study space. Technical

Services Quarterly, 27(4), 347-363. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/07317131003766009

Hua,

Y., Göçer, O., & Göçer, K. (2014). Spatial mapping of occupant satisfaction

and indoor environment quality in a LEED platinum campus building. Building and Environment, 79, 124-137. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.buildenv.2014.04.029

Lehto,

A., Toivonen, L., & Iivonen, M. (2012). University library premises: The

evaluation of customer satisfaction and usage. In J. Lau, A. Tammaro, & T.

Bothma (Eds.), Libraries driving access

to knowledge (pp. 289-314). Boston, MA: De

Gruyter Saur. http://dx.doi.org/10.1515/9783110263121.289

Montgomery,

S. E. (2011). Quantitative vs. qualitative - do different research

methods give us consistent information about our users and their library space

needs? Library & Information

Research, 35(111), 73-86. Retrieved from http://www.lirgjournal.org.uk/lir/ojs/index.php/lir/article/view/482

Norton,

H. F., Butson, L. C., Tennant, M. R., & Botero, C. E. (2013). Space

planning: A renovation saga involving library users. Medical Reference Services Quarterly, 32(2), 133-150. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02763869.2013.776879

Pierard,

C., & Lee, N. (2011). Studying space: Improving space planning with user

studies. Journal of Access Services, 8(4),

190-207. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/15367967.2011.602258

Preiser,

W. F. E., & Wang, X. (2008). Quantitative (GIS) and qualitative (BPE)

assessments of library performance. Archnet - IJAR: International Journal Of

Architectural Research, 2(1), 212-231. Retrieved from http://archnet.org/publications/5108

San

Francisco Public Library. (2000). Post-occupancy

evaluation of main library. Retrieved from http://sfpl.org/index.php?pg=2000043301

Shipley,

R., & Utz, S. (2012). Making it count: A review of the value and techniques

for public consultation. Journal of

Planning Literature, 27(1),

22-42. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0885412211413133

Vaska,

M., Chan, R., & Powelson, S. (2009). Results of a user survey to determine

needs for a health sciences library renovation. New Review of Academic Librarianship, 15(2), 219-234. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13614530903240635

Webb,

K. M., Schaller, M. A., & Hunley, S. A. (2008). Measuring library space use

and preferences: Charting a path toward increased engagement. portal: Libraries and the Academy, 8(4),

407-422. http://dx.doi.org/10.1353/pla.0.0014

Appendix

A

Third

Floor Survey Instrument

Appendix

B

Furniture

Lab Survey Instrument

![]()

Appendix

C

Observation

Data Collection Form

Appendix

D

Third

Floor Area Map

Appendix

E

Furniture

Pictures