Article

The Possibilities are Assessable: Using an Evidence Based Framework to Identify

Assessment Opportunities in Library Technology Departments

Rick Stoddart

Head, User & Research

Services

University of Idaho

Moscow, Idaho, United States

of America

Email: rstoddart@uidaho.edu

Evviva Weinraub Lajoie

Director, Emerging

Technologies & Services

Oregon State University

Libraries & Press

Corvallis, Oregon, United

States of America

Email: evviva.weinraub@oregonstate.edu

Received: 26 July 2014 Accepted:

21 Nov. 2014

![]() 2014 Stoddart and Weinraub Lajoie. This is an Open

Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

2014 Stoddart and Weinraub Lajoie. This is an Open

Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

Abstract

Objective

–

This study aimed to identify assessment opportunities and stakeholder

connections in an emerging technologies department. Such departments are often

overlooked by traditional assessment measures because they do not appear to provide

direct support for student learning.

Methods

–

The study consisted of a content analysis of departmental records and of weekly

activity journals which were completed by staff in the Emerging Technologies

and Services department in a U.S. academic library. The findings were supported

by interviews with team members to provide richer data. An evidence based

framework was used to identify stakeholder interactions where impactful

evidence might be gathered to support decision-making and to communicate value.

Results

–

The study identified a lack of available assessable evidence with some types of

interaction, outreach activity, and responsibilities of staff being

under-reported in departmental documentation. A modified logic model was developed

to further identify assessment opportunities and reporting processes.

Conclusion

–

The authors conclude that an evidence based practice research approach offers

an engaging and illuminative framework to identify department alignment to

strategic initiatives and learning goals. In order to provide a more complete

picture of library impact and value, new and robust methods of assessing

library technology departments must be developed and employed.

Introduction

Demonstrating value and impact is an ongoing and

evolving challenge for academic libraries. Often value is determined by the

impact library services and resources have with stakeholders and one of the

prominent populations served by academic libraries is students. University

administrators who determine library budgets and set organizational goals place

importance on how academic libraries meet student needs, contribute to student

learning, and advance institutional strategic teaching efforts. Thus,

identifying the points where a library’s resources and services intersect with

students provides potential opportunities to insert assessment measures that

will aid in articulating library value to stakeholders such as students and

university administrators. This article is about identifying assessment

opportunities and stakeholder connections using an evidence based research

framework.

Academic libraries offer many obvious intersections

with students and other stakeholders through their services points such as at

the reference or circulation desk, or through instruction and workshops that

deal directly with students and patrons. Assessing the impact of departments

engaged in library instruction, reference, and circulation is relatively well

established. Potential assessment of these areas can occur using transactional

metrics provided through circulation, reference, and attendance statistics. Additional

value can be determined by follow-up surveys, evaluating student work, or

connecting these transaction statistics to institutional data such as

grade-point-average or retention rates. However, academic libraries have units

such as cataloguing, technology departments, digitization units, and others

that may not have direct contact with students and patrons. This lack of direct

contact with stakeholders does not excuse these library departments from

library assessment efforts as libraries devote significant human, financial,

and technology resources to these areas and need to articulate a return on

these investments.

An essential contributor to library value is found

within library systems, web services, and emerging technologies departments.

Often these areas of library services are overlooked by traditional assessment

measures and efforts because they do not appear to provide direct support for

student learning. This is unfortunate, as technology units are a “crucial”

contributor to service organizations that deal primarily in information, such

as libraries (Braun, 1998, p. 64). Library technology departments offer

important services and expertise that certainly influence student learning,

researcher productivity, and library innovation but documenting this impact

remains an ongoing challenge. In order to provide a more complete picture of

library impact and value, new and robust methods of assessing library

technology departments must be developed and employed. However, care should be

taken to ensure that these library assessments be thoughtfully and effectively

integrated within existing workflows and structures. Libraries are encouraged

to take the time for a thorough self-examination before embarking on an

assessment project. This reflection is necessary in order to assist in

identifying the potential uses of the data, as well as to build a sustainable

assessment cycle.

The Emerging Technologies & Services (ETS)

department at Oregon State University Libraries & Press (OSULP) provides an

example of this departmental self-examination. In the fall of 2012, ETS engaged

in a qualitative research project to identify stakeholder intersections with

ETS activities and services. The primary intended outcome from this study was

to determine stakeholder intersection points from which ETS could insert future

assessment measures to articulate value and impact. This research project was

inspired and guided by the Evidence Based Library and Information practices

outlined by Booth (2009) and Koufogiannakis (2011). This study consisted of a

content analysis of departmental reports and weekly activity journals of ETS

members. These items were analyzed for interactions with stakeholders such as

students, faculty, and library professionals. An additional evaluation criterion

was applied by examining how departmental reports and activity journals

contributed to the advancement of the OSULP

Strategic Plan, and alignment to national library standards as these both

serve to outline library value and impact.

From these results ETS was able to draw informed

inferences about the department’s role in student learning, advancement of the OSULP Strategic Plan, and alignment to

national library standards. This data was further enhanced by interviews with

team members that provided greater detail, leading to the discovery of

under-realized connections between the library technology department and its

stakeholders. The outcomes of this research project for ETS included a series

of next steps to better capture evidence to convey impact, and a stronger

commitment to assessment efforts within the library. Interestingly, the

assessment activities highlighted areas in which the department was taking on a

leadership role that had not been identified previously. The outcomes renewed

the department’s focus on outreach beyond OSULP. From a library assessment

perspective, this project yielded a greater understanding of the potential all

library departments have to contribute to student learning, library and

university prestige, as well as providing meaningful value to library

stakeholders.

Emerging

Technologies and Services

The ETS department at OSULP encompasses more than

maintaining the computing and technology infrastructure for the library. The

vision of the ETS department is to: Pioneer efforts that transform access to

content and collections. Forge partnerships to expand current services and

explore new frontiers of library technology .This vision is translated by

the ETS department into innovative undertakings such as contribution to larger

open-source projects like Hydra; a community driven, Digital Asset Management

Solution (DAMS), translating OSULP press books into dynamic educational mobile

sites, transforming library spaces with student-centered technology, an in-house

developed study room reservation system, a friend-finder tool to aid study

groups, and collaborating with government and non-government entities on the

Oregon Explorer data portal. These innovative projects are reminiscent of the

stance some library administrators take that libraries have “an obligation to

drive technological change” (Bengtson & Bunnett, 2012, p. 702). This is the

stance embraced by ETS at OSULP.

ETS bridges both the management and the creation of

the technology environment within the OSULP library, or as Braun (1998)

describes it as “technology in context.” Braun points out, “Whereas the

application, creation, design, maintenance, and improvement of technology

itself are, of the domain of the engineer and scientist, managing technology in

the context, and for the benefit, of a firm, is the domain of the technology

manager” (p. 5). ETS is made up of equal parts of each side of Braun’s

technology dynamic of technology managers and designers. At the time of this

research study, the unit included two tenure track librarians who performed

research about technology application, instruction, and use; two professional

faculty, one of whom acted in the role of overall “technology manager”; six

staff including programmers developing new applications and software; and

various student workers.

ETS is a very productive and dynamic department that

allows the library to remain innovative and relevant to users. After

collections and staffing costs, technology is the largest expenditure line in

the library. If you exclude salaries, technology costs are the library's

largest expenditure after collections. Such a significant resource allocation

makes clear that OSULP sees value in the work and resources ETS provides not

only to the library but also its users. Despite the apparent value the library

places on this department, ETS remained challenged to convey its impact in a

meaningful way to campus stakeholders, such as university administrators, who

place an emphasis on assessing student learning and success in the classroom.

The most common way libraries articulate their contribution to student learning

is through their instruction program and workshops. ETS has not traditionally

participated in teaching and instruction activities. However, that is not to say

that ETS does not interact with students, contribute to student learning, or

offer education opportunities to students. In fact, a recent report (Grajek,

2014) identified “improving student outcomes” through “strategically leveraging

technology” as a top ten issue for educational technologists. With this need to

strategically leverage technology to improve student outcomes in mind, an

environmental scan was undertaken to determine how ETS’s accomplishments might

contribute, whether directly or indirectly, to student learning, university

priorities, and national standards.

The EBLIP Cycle as a Research Framework

Library

assessment is interested in evidence that can convey impact. This research project

is tasked with identifying stakeholder interactions where impactful evidence

might be gathered to inform decisions and communicate value. One framework that

supports evidence based processes is found within the literature of evidence

based librarianship (EBL). Crumley and Koufogiannakis (2002) frame evidence

based librarians as “a means to improve the profession of librarianship by

asking questions as well as finding, critically appraising, and incorporating

research evidence from library science (and other disciplines) into daily

practice. It also involves encouraging librarians to conduct high quality

qualitative and quantitative research” (p. 62). Eldredge (2000) suggested EBL

is “an applied rather than

theoretical science. EBL merges scientific research with pressing needs to

solve practical problems…. EBL provides a framework for self-correction as new

information becomes available that suggests new directions or methods” (p.

290). The nature of EBL as being applied, practical, and informing daily

practice, suggestive of new directions, and new evidence resonated with the

authors as a framework to construct the ETS assessment project.

Recently EBL practices and models have become more

inclusive of answering day-to-day library management questions not simply

targeted research projects. Booth (2009) points out that “(i)t is simplistic to

assume that a complex managerial situation will yield a single question as in

the classic (evidence based practice) formulating or framing a question” (p.

342). Indeed, our project demonstrates the need to take a wider more iterative

and reflective approach to understanding the problem to be addressed. Booth

(2009) concurs as “a management problem may be more effectively tackled by

achieving a wider, more holistic perspective. Within the context of team

working

and collaboration it is extremely valuable for a team

to arrive at a shared understanding of the problem to articulate this

collectively” (Booth, 2009, p. 342). This is the very outcome ETS and the

Assessment Librarian sought in uncovering the assessment possibilities within

the ETS department. As Booth notes, “Each team member has a contribution to

make, which itself needs to be valued and carried forward within the

decision-making process (p. 342). Booth notes further, “(g)iven that library

services are human mediated, a significant contributor to the success of any

service change is the motivation, involvement, and commitment of the team (p.

343). The more collaborative EBL model as Booth proposes thus provides an

appropriate framework to evaluate the assessment opportunities within ETS. This

newer model is made up five steps (Booth 2009).

●

Articulate:

Articulating the problem

●

Assemble:

Assembling the evidence base

●

Assess:

Assessing the evidence

●

Agree: Agreeing

on the actions

●

Adapt:

Adapting the implementation

This model is what guided the process to determine the

assessment potential and capability of the ETS department at OSULP. This

framework was further enhanced by the set of questions Koufogiannakis (2011)

provides regarding gathering practiced based evidence in libraries.

This EBL framework not only provides a pathway to

begin to gather evidence of assessment and impact, it also provides a tool to

help identify the places and types of evidence that may need to be gathered in

a more deliberate or strategic manner. This elegantly mirrored our project

goals: determine what library assessment evidence and opportunities are already

being leveraged as well as where gaps may exist that might be filled in with

additional research effort or assessment tools.

ARTICULATE: Articulating the Problem

The overarching question driving this research study

was:

●

What types

of interactions does ETS have with stakeholders and students?

Answering this

question would help ETS identify opportunities to target assessment

interventions that strategically gather evidence to convey impact to

stakeholders. This broad research question was refined further into three more

specific questions to help better understand the ETS department’s impact and

contribution to library and university outcomes valued by stakeholders.

●

Where/How is

ETS impacting student learning?

●

Where/How is

ETS advancing the library’s Strategic Plan?

●

Where/How is

ETS contributing to meeting national library standards?

ASSEMBLE: Assembling the Evidence Base

Once the research questions were articulated, the next

step in the EBL framework was to gather available evidence about the ETS

department’s actual and potential contributions to the libraries, the

university, and to the national assessment guidelines. The process was guided

by the evidence gathering questions suggested by Koufogiannakis (2011): What do I already know?; What local evidence is available?; What does the literature say?; and What other information do I need to gather? What do I already know?

The ETS department was well integrated into the 2012 -

2017 OSULP Strategic Plan (Oregon State University Libraries and Press, n.d.).

There were a large number of strategic activities within the plan that were

spearheaded directly by ETS. These items have been identified in internal

documents and progress was reported through quarterly library reports. These

reports captured the traditional criteria of departmental accomplishments, projects,

personnel issues, and challenges. Beyond these reports, there was little in the

way of formal assessment activities such as user feedback surveys, return on

investment projects, or other evidence gathering procedures to tie ETS efforts

to library and campus-wide outcomes. Most projects were documented as

“completed” or “in-progress” on reports but were lacking in their ability to

articulate project impacts on student success, faculty productivity, or

university advancement.

Based on departmental reports and quick scan of known

activities, ETS offers many opportunities for student interaction. This occurs

through direct interactions with student ETS employees and the hosting of

student internships. Students are also recruited by ETS to test new technologies

through usability testing. Interactions also occur with users when

troubleshooting access issues to library resources. ETS also has indirect user

interactions through the development and maintenance of the technology students

interact with, as well as through the acquisition and support of the

educational technologies that underpin the library’s instruction efforts.

Consultations also transpire with constituents such as library staff,

university departments and faculty, and stakeholders outside OSULP. However,

despite knowing about these interactions, details of the frequency, quality,

and assessability of these interactions were unclear. Thus, ETS continued to

have trouble translating these interactions into impacts within the currently

available and accepted assessment reporting structure and was therefore not

accurately conveying the department’s overall contribution to library and

student success.

What Local

Evidence is Available?

OSULP

gathers local evidence from user feedback tools like LibQual+, occasional

surveys of patrons on technology use, as well as statistics gathered on library

equipment in public/teaching areas. This data provides ETS with indirect

evidence of contribution to library value. However, these measures are not

comprehensive in nature, and fail to articulate the full array of interactions

ETS has with stakeholders. Further potential evidence of ETS’s impact is

articulated in library departmental reports but these documents often provide a

summary of activities not a full scope of data for additional analysis. In

summary, local evidence available to demonstrate ETS’s impact was limited and

highlights the need for additional assessment practices in this area.

The body of literature concerning library assessment

of student learning, space evaluation, and collection usage is growing at

healthy rate. Unfortunately, one area that needs some additional development is

capturing the contribution to assessment efforts from under-represented library

units such as ETS. Little (2013) points out, “Academic libraries, especially

those with research missions and relatively large budgets, have also not paid

as much attention as might be desired to the assessment and evaluation of

library technologies…” and the accompanying infrastructure and services (p.

596). Most studies found that the library literature focused on evaluating

specific technologies rather than the overall services and impact library

technology departments might provide. Such is the case with Dougherty (2009)

who suggests that strategically evaluating library information technology is an

even more critical need as a result of recent economic troubles. Dougherty

suggests “measuring performance,” examining usage statistics, and soliciting

constituent feedback as a few strategies to consider when thinking about

managing technology costs. Ergood, Neu, Strudwick, Burkule, and Boxen. (2012)

echo Dougherty’s concerns: “In adapting to the many changes facing us today,

the development of an effective strategy for identifying and evaluating

emerging technologies is vital” (p. 122). Despite these recommendations by

Dougherty (2009), Ergood et al. (2012), and Little (2013) to examine, evaluate,

and assess emerging technologies and library technology units; the library

literature is lacking in research to aid in such projects. Ergood et al. (2012)

found the same research gap noting: “While the professional literature covers

emerging technologies and social media in libraries pretty well, there is a gap

in coverage of specific planning and staffing approaches to such technologies,

whether in libraries or elsewhere” (p.124). This lack of literature also

extends to works addressing overall library technology units such as ETS.

A review of the academic literature revealed a few

broad themes associated with technology units in organizations and value

assessment. In general, the library literature focused on the technology tools

themselves, not the assessment of departmental impact. For example, Little

(2013) writes about using Google Analytics and the usefulness of usability

studies as a way to assess how useful the technology is. Dash and Padhi (2010)

write about the various library assessment tools available and how they assess

library technologies, but again, ignore the department supporting those tools.

The information technology literature is focused in much the same way, with an

emphasis on IT infrastructure, purchasing, and the importance of customer

service but little about broader outcomes such as organizational success and

external stakeholder impact.

Though not specifically about libraries or library

technology, the area of technology assessment offers some research of general

interest. For example, Braun (1998) provides a well thought-out examination of

technology assessment in the broader sense concerning the potential impacts on

society, government, and businesses. Braun defines technology assessment as “a

systematic attempt to foresee the consequences of introducing a particular

technology in all spheres it is likely to interact” (p. 28). This definition

provides some guidance to the assessment of library technology departments in

suggesting that all spheres of interaction with their services be considered

including student learning or other stakeholder impacts.

Examining the business literature for articles about

assessing organizational unit value and contribution to external stakeholder

value also yielded limited results. In fact some research suggests, that in addition

to ignoring assessment measures altogether, focusing too heavily on certain

performance measurements for assessment can be detrimental to an organization’s

measures of impact and effectiveness (Meyer & Gupta, 1994). For example,

Meyer and Gupta talk of a process called “perverse learning” wherein

individuals learn which metrics are emphasized by administrators and only put

efforts into those activities that are being measured and ignore those

activities that are not. Such “perverse learning” can damage the accuracy of

performance measures as well as create disconnect between an organization’s

purpose and the actions it actually emphasizes (pp.339-340). This speaks to the

need to revisit performance measures periodically, align them to organizational

goals, and refresh or develop new metrics as needed. In the case of OSULP, the

need was apparent to balance evidence gathering across the organization not

simply the areas that were traditionally leveraged to gather stakeholder impact

such as student learning via library instruction or through student computer

usage statistics in library learning commons.

Little (2013) reminds us that, “Assessment should be

built in to everything thing we do, including our technology programs,

planning, and services” (p.597). Nguyen and Frazee (2009) emphasize that

strategic technology planning is required within higher education to avoid

haphazard implementation of tools and resources. Braun (1998) in talking about

the wider assessment of technology in society, the environment, and within

organizations suggests that the “purpose of technology assessment is to look

beyond the immediately obvious and analyze the ramifications of given

technology in as wide-ranging and far-sighted manner as possible” (p. 1). In

assessing library technology units, one must look beyond the “immediately

obvious” criteria of cost and use, and expand the analysis to more

“wide-ranging and far-sighted” impacts such as student learning and stakeholder

value. These “wide-ranging and far-sighted” impacts are often articulated in a

library’s strategic plan or mission and suggest criteria for library technology

units to consider assessing value. Cervone (2010) concurs “when evaluating

emerging technologies or innovative new practices and services, it is critical

to ensure that the path your library is going down is in sync with the mission

of the parent institution” (p. 240). How library technology departments align

their efforts and services to advance the library’s strategic plan or mission

is one avenue to examine value and determine criteria for assessment. Within

information technology literature, this congruence of technology efforts and

organizational goals is known as “alignment” or “fit” (Bergeron, Raymond, &

Rivard, 2004). Such alignment theories posit that organizations “... whose

strategy and structure are aligned should be less vulnerable to external change

and internal inefficiencies and should thus perform better” (p. 1004).

Similarly, as within the relationship of technology

assessment and strategic management, Braun (1998) points out: “The firm needs

strategic management for long-term survival and prosperity. Technology is vital

to the life of the firm and is one of the most important tools available for

taking up a certain strategic stance. Thus technology needs specialist

strategic management. Strategic management of technology requires an

information input in the form of technology assessment” (p. 55). Such

assessments are essential to determine the strategic fit of technology units within

libraries as they represent potential areas of tension within the overall

organization. As units like ETS are often synonymous with innovation and

experimentation, Cervone (2010) points out that, “Innovation without

demonstrable value being added to processes or services is not something that

is typically valued by an organization’s leadership” (p. 240). Ergood et al.

(2012) agree with regards to emerging technologies that, “Given the strong

culture of assessment in libraries, an integral last step is to consider the

metrics to be used in determining the effectiveness of the tools our libraries

implement” (p. 125). The examination of the “effectiveness” of these tools on

the student learning valued by library stakeholders and articulated in library

strategic plans is what framed the research questions used to guide this study.

This study attempts to examine the strategic alignment of the ETS department at

OSU Libraries, as a first step in building more meaningful assessments that

will assist in articulating value and measuring performance. These assessments

will further align the ETS department within OSULP library’s overall strategic

plan that emphasizes student success.

What Other

Information Do I Need to Gather?

As part of the process, the researchers reviewed ETS

departmental quarterly reports and noted a scarcity of detailed assessment and

impact evidence being reported. Additionally, there was an absence of

assessment processes built into departmental projects. Combining these two

factors with a lack of literature evaluating library technology departments, it

was determined that there was a real research need to examine the assessment

possibilities associated with library technology departments such as ETS.

The researchers’ initial step was to perform an

informal research project to gather examples of ETS activities for potential

assessment. ETS members were asked to maintain a weekly journal of activities.

Similar “diary” studies have been successfully used with library patrons to

better understand information seeking behavior (Xu, Sharples, & Makri.

2011; Lee, Paik, & Joo 2012). Sheble & Wildemuth (2009) in describing

the potential of diary studies as a library research methodology note: “Diary

methods are more likely to capture ordinary events and observations that might

be neglected by other methods because participants view them as insignificant,

take them for granted, or forget them (p. 213). The ETS member activity

journals were undertaken to not only capture potentially assessable activities,

but to also gain a better understanding of the day-to-day activities staff were

performing that might be viewed as “insignificant” but which in reality are a

high impact practice of value to library stakeholders. The review of these

day-to-day tasks yielded a clearer understanding of what actions were necessary

to accomplish projects recorded in the quarterly reports. The initial data from

this quick project provided a starting point to uncover the library assessment

opportunities within the department.

ASSESS: Assessing the Evidence

While there was a paucity of assessment data readily

available in the ETS department, this is not to say there was no evidence to

assess. As mentioned in the previous section, a brief assessment project was undertaken

to gather and list some of the daily activities of ETS members. These daily

activity journals, as well the past two years of departmental quarterly reports

offered a body of evidence to evaluate for alignment with library goals and

strategic plan. Below is a summary of the data available to be analyzed:

●

ETS

Quarterly Reports (n=9)

●

partial

FY2011 to FY2013

●

ETS Member

Activity Journals (n=9)

●

Staff

members kept hourly journals for a one week. This activity was performed twice

in a 20-week period.

●

ETS staff

members were asked to note each activity, time spent performing the task,

who/what department it impacted, and with whom they may have collaborated to

accomplish each task.

These departmental

quarterly reports and ETS member journals were analyzed using content analysis

to identify activities, tasks, and accomplishments that aligned with strategic

library documents. These documents included the OSULP Strategic Plan (Oregon State University Libraries and Press,

2010), the OSU Learning Goals for Graduates (Oregon State University

Provost, 2010), and the Association of College &

Research Libraries (ACRL) Standards

for Libraries in Higher Education (Association of College and Research Libraries,

2011). These

documents were selected because they articulated library and university-wide

strategic goals for student learning, technology, and library efficiencies. The

data was coded based on four sets of criteria developed from these documents,

which yielded sixty codes for the content analysis. These codes were grouped in

these general areas:

1.

Activities

that involved Stakeholders or Collaborators

(18)

2.

Activities

that contributed to OSULP Learning Goals

for Graduates (7)

3.

Activities

that contributed to OSULP Strategic Plan

(4)

4.

Activities

that related to specific ETS responsibilities in OSULP Strategic Plan (11)

5.

Activities

that met one of the ACRL Standards for

Libraries in Higher Education (9)

6.

Activities

that related to specific technology aspects of the ACRL Standards for Libraries in Higher Education (11)

These content areas were identified because they

contained potential contexts in which assessment could occur to derive impact

or value ETS has at a library-wide, campus, and national level. The intended

outcome for this content analysis was to identify gaps and strengths within

ETS. The ultimate goal was to establish where stakeholder value intersected

with ETS projects and services. Problematizing the goal of strategic alignment

of ETS raised these specific research questions:

●

Where does the ETS department have

direct student contact?

·

What areas of the OSULP learning

goals are being advanced?

·

How are they being assessed, if they

are at all?

●

Is the ETS department aligned with

the library’s needs and strategic plan?

·

What activities demonstrate a

contribution to the OSULP Strategic Plan?

●

How does the ETS department

contribute to library success in terms of national standards of excellence?

·

What activities demonstrate a

contribution to the ACRL Standards for Libraries in Higher

Education?

The ETS employee activity journals and department

quarterly reports yielded 302 excerpts for content analysis. For example, one

of the activity journals noted: "Continue

Working on Classroom Build update (Library Faculty)/All classroom users. On and

off all day. 4 days". This excerpt was coded for the stakeholders this

activity impacted, in this case instruction librarians and students as an

indirect interaction. This activity was then coded as contributing to the OSULP Strategic Plan goal of Enriching

Academic Impact and Educational Prosperity, as well as the ACRL Standards for Libraries in Higher Education

principle of educational role. Codes derived from the OSULP Learning Goals for Graduates were only applied if the ETS

activity was a direct student interaction. Because the departmental reports did

not emphasize this interaction in the OSULP reporting template, there were few

ETS activities coded with set.

One initial finding that became apparent during the

content analysis was that the departmental reports did not provide an accurate

representation of all the activities ETS undertook. Furthermore, the ETS member

daily journal exercise was guided by a worksheet without any formal training in

how to capture personal activity data. This lack of formal training resulted in

each employee providing differing levels of detail about their daily

activities. That said, this evaluation of ETS activities, efforts, and projects

was intended to be a starting point for future assessment activities. With that

limited goal in mind, this research project was viewed as successful by the ETS

department as this study yielded actionable data to inform future

decision-making.

AGREE: Agreeing on the Actions

The next

stage of the evidence based practice model is agreeing on what the evidence

shows and what proposed actions may result from the assembled evidence. In the

case of the limited available evidence from the literature review and the data

generated in the content analysis of departmental reports and member activity

journals, ETS was presented with a variety of results to consider.

Renewed Emphasis on Assessment, Evidence Gathering, and Reporting

One of the

major areas of consensus was the need to have more evidence for assessment

purposes. This consensus point is the inspiration for this project but it is

also demonstrated and reiterated in the lack of available assessable evidence.

For example, one of the areas where the researcher knew that ETS had strong direct

impact was with student employees. Student employees, after receiving

specialized training, are assigned a project that they manage from beginning to

end. This type of student engagement, surprisingly, was not adequately

articulated or captured in the departmental quarterly reports or daily activity

journals. Another example supporting the gap in available local evidence is

found in how library space interactions are documented by ETS members in the

daily library activities such as in support of various teaching and public

services( i.e. computers in the classrooms and labs, printers, scanners, tablet

computers, etc.). While time spent on issues relating to library space was

“known” by ETS staff, and the responsibilities themselves were written into the

job descriptions of at least three individuals in the department, this hadn’t

been adequately documented and was seen as “missing” from the ETS content

analysis. As a result of this insight, it was agreed that a continued effort to

build better evidence-gathering practices and reporting within ETS would be

emphasized.

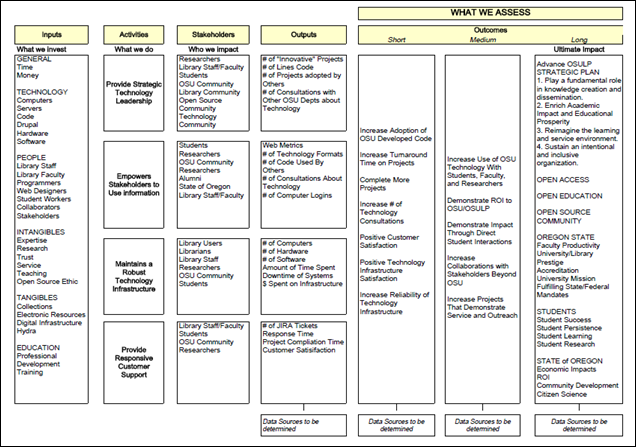

To better

articulate ETS’s assessment opportunities, a modified logic model was developed

based on the outcomes of the content analysis (see appendix). Logic models are

used in performance management and program evaluation to clearly lay out an

organization’s inputs, outputs, activities, and outcomes (McLaughlin &

Jordan 1999; Millar, Simeone & Carnevale 2001). Logic models serve to build

common understanding, identify priorities, and articulate performance

indicators for ongoing assessment (McLaughlin & Jordan, 1999, p.66). The

ETS logic model was seen as one way to further identify assessment

opportunities and reporting processes. The ETS logic model provided a visual

representation of the inputs (money, time, expertise) and outputs (code,

project completions) that the department generated. Further, these inputs and

outputs were connected both to the stakeholders impacted as well as to the

overall intended outcomes articulated in the OSULP Strategic Plan such as student success and faculty

productivity. The ETS logic model serves as a blueprint to help begin thinking

more deeply about the assessments needed to connect what ETS does to the

overall outcomes of the library and university.

Embracing Library Outreach and Collaboration

As a result

of this study, a number of “I knew this but now we have evidence” moments came

to light, such as documenting ETS efforts around supporting library technology.

However, the most well documented strategic alignment was around collaborative

and outreach ETS activities. Suddenly, there was a major area of documented

impact, articulated in the OSULP

Strategic Plan and values, University learning goals, and national learning

standards that ETS could own and build on. Collaboration is one of the core

values of OSULP and is featured prominently throughout the libraries’ strategic

plan. These collaborative outreach activities were well documented in ETS

departmental quarterly reports, and it became clear through the reporting

activity, that those projects were also a major part of the day-to-day

activities of members of the department. Staff members worked directly with

branch libraries and state agencies, as well as collaborating on shared

services with other universities. Despite the robust evidence of collaboration

and outreach, ETS staff recognized that the quarterly reports were still

under-reporting the breadth and depth of the department’s activities and impact

on stakeholders thus suggesting that there was additional evidence of

collaboration and outreach that was still not being documented. Agreement was

reached that ETS would build on this newly articulated strength of

collaboration and outreach as one way to demonstrate strategic alignment with

the library and university, as well as continue to develop ways to gather

evidence to support these endeavours.

To better support ETS’ strategic alignment with

library collaboration and outreach goals, and to further emphasize this role to

stakeholders, ETS revamped their mission and vision statements to highlight the

collaborative work the department engages in to provide outstanding service and

outreach (Oregon State University, n.d.).

At the conclusion of this ETS content analysis

project, the researchers agreed that for the data collected to have real impact

within the library, it would be useful in the future to undertake a

library-wide content analysis of all library department reports as a point of

comparison. Such a cross-departmental analysis of departmental quarterly

reports would better articulate collaboration across units as well as impact on

stakeholders within the library. Additionally, this kind of library-wide

content analysis of reporting might likely uncover other hidden areas of impact

such as with collaboration and outreach in ETS, as well as gaps in evidence

gathering and reporting.

The researchers concluded that holding a training

session in the library about reporting best practices might be one way to

address gaps in reporting content. Quarterly reports in the library are

inconsistent, and the details reported through those reports differ from

department to department. Such a training session would highlight the

importance of consistent reporting for evidence gathering as a tool for

decision-making and demonstrating strategic alignment to stakeholders. Now that

the OSULP Strategic Plan has been in

place for over two years, a technique like this reporting model offers an easy

way to assess effort, impact, and advancement of strategic initiatives. The

data collected through reporting exercises like this, could have significant

impact on the way that future strategic planning sessions move forward for the

library; on how the library conveys its value to university administrators, and

can help with fundraising activities though highlighting impact in areas that

aren’t obvious immediately.

ADAPT: Adapting the Implementation

In the evidence based practice model Booth (2009)

proposed, adapting the implementation

is the final step. This stage acknowledges that local application of evidence

based interventions may involve modification, flexibility, and retooling. This

step emphasizes that evidence based practices, like library assessment, are

iterative. The researchers in this initial examination of ETS embraced this

fact, as the gathering of evidence and resulting content analysis were seen as

first steps to building a sustainable, flexible, and personalized ETS

assessment model. The implementation of suggested outcomes is still a work in

progress and will continually be assessed and reassessed as ETS builds their

departmental assessment resources and culture. A content analysis of

departmental reports may not be necessary for every library technology unit to

undertake, neither may displaying outcomes in a departmental logic model; but

the acts of articulating the question, assembling evidence, assessing the

evidence, agreeing on outcomes based on the evidence, and finally the adaption

of outcome implementation to local needs suggest a template for all libraries

to consider for assessment, strategic fit, and demonstrating value. This final

step is about ‘owning’ the application of your EBP research, or similarly

developing and embracing your own assessment process to meet organizational

needs. This examination of ETS suggests that an evidence based practices model

offers an adaptable research approach to begin iterative assessment activities

within libraries.

The possibilities are assessable. The challenge for libraries

is to identify these assessment opportunities and take advantage of them as

means to gather evidence to support change and convey impact. Demonstrating

value to stakeholders and documenting evidence of contributing to a

university’s mission and strategic initiatives are essential undertakings for

all units of an academic library. Bengston and Bunnett (2012) posit that,

“Libraries, if they want to be seen as vital, relevant, and positioned as key

players in the information handling of the future, must actively engage with

technology on every level” (p. 705). Library technology units, such as ETS at

OSULP, demonstrate such a commitment. At the same time, the managing of library

innovation and technology must also be assessed for value to the organization.

As Cervone (2010) reminds us, these efforts must be in “sync” with the parent

organization. An evidence based practice research approach offers an engaging

and illuminative framework to identify department alignment to strategic

initiatives and learning goals. The EBP process proposed by Booth (2009)

provides a step-by-step process for library departments, such as ETS, to begin

gathering and assessing evidence of impact and value (see Table 1). In this

project’s instance, the first step was a self-assessment of departmental impact

and potential impact areas. This self-reflection proved invaluable resulting in

refocus of the department’s mission and re-emphasis on developing new

assessment practices and reporting.

Table 1

Application of the EBP Process (Booth, 2009) to the

ETS Department

|

EBP Model |

Emerging Technologies & Services

Department |

|

Articulate the Question |

What

intersections does ETS have with stakeholders? Where/How

is ETS impacting student learning? Where/How

is ETS advancing the library’s strategic plan? Where/How

is ETS contributing to meeting national library standards? |

|

Assemble the Evidence |

Strategic

Documents Departmental

Reports Weekly

Activity Journals Literature |

|

Assess the Evidence |

Content

Analysis of Department Reports |

|

Agree on the Actions |

Renewed

Emphasis on Assessment, Evidence Gathering, and Reporting Embracing

Library Outreach and Collaboration |

|

Adapting the Implementation |

Results

from evidence gathering to inform future ETS assessment activities. |

The evidence based practices framework provides

libraries with guidance, as well as with a suggested research process in

gathering evidence that may inform library-wide assessment practices. Kloda

(2013) sees a clear connection between assessment and evidence based practices

as iterative cycles that support rigorous inquiry and change.

Most academic libraries want to be innovative in their

practices and culture. Innovation is desired across many library departments

but is especially embedded in library technology units. Bengston and Bunnett

(2012) note, “Organizations that wish to support innovations cannot hope to do

so by merely stating that they support innovation or by inviting their

employees to innovate” (p. 700). Library assessment and evidence gathering are

key to conveying innovation, as well as identifying and marketing contributions

to student success or organizational mission. The EBL process offers a robust

framework for project management, iterative development, and collaboration

engagement for identifying and developing assessment opportunities. The

possibilities are, indeed, assessable. Libraries only need to build

evidence-gathering processes within their ongoing activities and efforts in

order to realize this opportunity in full.

Bengtson,

J., & Bunnett, B. (2012). Across the table: Competing perspectives for

managing technology in a library setting. Journal

of Library Administration, 52(8),

699-715. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01930826.2012.746877

Bergeron,

F., Raymond, L., & Rivard, S. (2004). Ideal patterns of strategic alignment

and business performance. Information

& Management, 41(8), 1003-1020.

Booth, A. (2009). EBLIP five-point-zero:

Towards a collaborative model of evidence based practice. Health Information and Libraries Journal, 26(4), 341–344. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00867.x

Braun,

E. (1998). Technology in context:

Technology assessment for managers. London: Routledge.

Cervone.

H. F. (2010). Emerging technology, innovation, and the digital library. OCLC Systems & Services, 26(4), 239

–242.

Crumley E., and Koufogiannakis D.

(2002). Developing evidence based librarianship: Practical steps for

implementation. Health Information and

Libraries Journal

19(2), 61-70. http://dx.doi.org/

10.1046/j.1471-1842.2002.00372.x

Dash, N.K., & Padhi, P. (2010).

Quality assessment of libraries. DESIDOC Journal

of Library & Information Technology, 30(6), 12-23. Retrieved from http://publications.drdo.gov.in/ojs/index.php/djlit/index

Dougherty,

W. C. (2009). Managing technology during times of economic downturns:

challenges and opportunities. The Journal

of Academic Librarianship, 35(4),

373-376. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2009.04.007

Eldredge J.D. (2000). Evidence-based

librarianship: An overview. Bulletin of

the Medical Library Association, 88(4),

289-302. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/journals/72/

Ergood,

A., Neu, R. C., Strudwick, J., Burkule, A., & Boxen, J. (2012). Five heads are

better than one: The committee approach to identifying, assessing, and

initializing emerging technologies. Technical

Services Quarterly, 29(2),

122-134. http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1080/07317131.2012.650611

Grajek, S. (2014). Top 10 IT issues,

2014: Be the change you see. Educause

Review. March/April. 10-46. Retrieved from http://www.educause.edu/ero/article/top-ten-it-issues-2014-be-change-you-see

Kloda, L. (2013). From EBLIP to

assessment. Presentation at 2013 Evidence Based Library & Information

Practice conference. May. University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon, Canada.

Retrieved 27 Nov. 2014 from http://www.slideshare.net/lkloda/kloda-eblip-7-lightning

Koufogiannakis. D. (2011).

Considering the place of practice-based evidence within Evidence Based Library

and Information Practice (EBLIP). Library

and Information Research 35(111),

41-58. Retrieved from http://www.lirgjournal.org.uk/lir/ojs/index.php/lir

Lee, J. Y., Paik, W., & Joo, S. (2012).

Information resource selection of undergraduate students in academic search

tasks. Information Research, 17(1), 5. Retrieved from http://www.informationr.net/ir/

Little,

G. (2013). Squaring the circle: Library technology and assessment. The Journal of Academic Librarianship, 396, 596-598. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2013.09.002

McLaughlin,

J. A., & Jordan, G. B. (1999). Logic models: A tool for telling your

programs performance story. Evaluation

and Program Planning, 22(1),

65-72. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0149-7189(98)00042-1

Meyer, M. W., & Gupta, V.

(1994). The performance paradox. Research

in Organizational Behavior, 16,

309-369.

Millar,

A., Simeone, R. S., & Carnevale, J. T. (2001). Logic models: A systems tool

for performance management. Evaluation

and Program Planning, 24(1),

73-81. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0149-7189(00)00048-3

Nguyen, F., & Frazee, J. P.

(2009). Strategic technology planning in higher education. Performance Improvement, 48(7),

31-40. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/pfi.20093

Sheble, L., & Wildemuth, B.M.

(2009). Research diaries. In B.M. Wildemuth (Ed.), Applications of social research methods to questions in information and

library science (pp. 211-221). Westport, Conn.: Libraries Unlimited.

Xu, S., Sharples, S., & Makri,

S. (2011). A user-centred mobile diary study approach to understanding

serendipity in information research.

Information Research,16(3), 7.

Retrieved from http://www.informationr.net/ir/

Appendix

ETS Logic Model