Article

Identifying the Visible Minority Librarians in

Canada: A National Survey

Maha Kumaran

Liaison Librarian

Leslie and Irene Dubé Health Sciences Library

University of Saskatchewan

Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, Canada

Email: maha.kumaran@usask.ca

Heather Cai

Information Technology Services Librarian

McGill University Library

Montréal, Quebec, Canada

Email: heather.cai@mcgill.ca

Received: 30 Oct. 2014 Accepted: 8

Apr. 2015

![]() 2015 Kumaran and Cai. This is an Open

Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

2015 Kumaran and Cai. This is an Open

Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

Abstract

Objective

–

This paper is based on a national survey conducted in late 2013 by the authors,

then co-moderators of the Visible Minority Librarians of Canada (ViMLoC)

Network of the Canadian Library Association (CLA). It is a first survey of its

kind, aiming to capture a snapshot of the demographics of the visible minority

librarians working in Canadian institutions. The authors hoped that the data

collected from the survey and the analysis presented in this paper would help

identify the needs, challenges and barriers of this group of librarians and set

future directions for ViMLoC. The authors also hoped that the findings would be

useful to library administrators, librarians, and researchers working on

multicultural issues, diversity, recruitment and retention, leadership, library

management, and other related areas.

Methods

–

An online survey questionnaire was created and the survey invitation was sent

to visible minority librarians through relevant library association electronic

mail lists and posted on ViMLoC’s electronic mail list and website. The survey

consisted of 12 questions: multiple-choice, yes/no questions, and open-ended.

The survey asked if the participants were visible minority librarians. If they

responded “No,” the survey closed for them. Respondents who did not identify

themselves as minority librarians were excluded from completing the survey.

Results

–

Of the 192 individuals that attempted, 120 who identified themselves as visible

minority librarians completed the survey. Of these, 36% identified themselves

as Chinese, followed by South Asian (20%) and Black (12%). There were 63% who

identified themselves as first generation visible minorities and 28% who

identified themselves as second generation. A total of 84% completed their

library degree in Canada. Equal numbers (38% each) identified themselves as

working in public and academic libraries, followed by 15% in special libraries.

Although they are spread out all over Canada and beyond, a vast majority of

them are in British Columbia (40%) and Ontario (26%). There were 38% who

identified themselves as reference/information services librarians, followed by

“other” (18%) and “liaison librarian” (17%). A total of 82% responded that they

worked full time. The open-ended question at the end of the survey was answered

by 42.5% of the respondents, with responses falling within the following broad

themes: jobs, mentorship, professional development courses, workplace issues,

general barriers, and success stories.

Conclusions

–

There are at least 120 first, second, and other generation minority librarians

working in (or for) Canadian institutions across the country and beyond. They

work in different kinds of libraries, are spread out all over Canada, and have

had their library education in various countries or in Canada. They need a

forum to discuss their issues and to have networking opportunities, and a

mentorship program to seek advice from other librarians with similar

backgrounds who have been in similar situations to themselves when finding jobs

or re-pursuing their professional library degrees. Getting support from and

working collaboratively with CLA, ViMLoC can be proactive in helping this group

of visible minority librarians.

Introduction

In

December 2011, the Visible Minority Librarians of Canada (ViMLoC) Network

(http://vimloc.wordpress.com/) was established through the Canadian Library

Association (CLA). The focus of the network was to create a forum for visible

minority librarians in Canada. In January 2013, ViMLoC was invited to

participate in a panel presentation at the Ontario Library Association (OLA)

Super Conference. At the presentation, ViMLoC sought ideas from the attendees

on future directions for ViMLoC. Based on the feedback, two future directions

were identified and added to ViMLoC’s agenda: that ViMLoC 1) gather statistical

information of visible minority librarians working in Canadian institutions;

and 2) create a mentorship program for this group. In December 2013, the

authors, then co-moderators of ViMLoC, distributed an online survey to gather

statistical information on visible minority librarians at Canadian institutions

both in and outside of Canada.

The principal aim of the survey was to

collect foundational data on the number of visible minority librarians working

in Canadian institutions. The authors hoped that any additional information

collected through this survey would help ViMLoC identify the needs, challenges

and barriers of this group of librarians and set future directions for

ViMLoC.

This

is the first survey of its kind in Canada designed to learn directly from

visible minority groups for such information as:

- Which

ethnic groups these librarians belong to

- Whether

they were first or second generation Canadians

- Their

educational qualifications and experiences

- The types of

institutions in which they are currently employed

- The types

of positions they hold, and,

- Whether

they are employed full-time or part-time.

The

authors hope that the quantitative data and the qualitative analysis of the

survey presented in this paper will be useful to library administrators,

librarians, and researchers working on multicultural issues, diversity,

recruitment and retention, leadership, library management, and other related

areas.

Research

background

The

Canadian Employment Equity Act (Government of

Canada, 2014) uses

the term “Visible Minorities” and

defines them as “persons, other than Aboriginal peoples, who are non-Caucasian

in race or non-white in colour” (Statistics

Canada, 2012a).

Statistics Canada’s 2011 National Household Survey (2013) states that there are

13 categories that make up the visible minority variable - Chinese, South

Asian, Black, Arab, West Asian, Filipino, Southeast Asian, Latin American,

Japanese, Korean, visible minority not included elsewhere, multiple visible

minority, and not a visible minority. South Asian includes East Indian (from

India), Pakistani, and Sri Lankan. Southeast Asian includes Vietnamese,

Cambodian, Malaysian, Laotian, and others, and West Asian includes Iranian,

Afghan, and others (Statistics

Canada, 2013).

The

Immigration

and Ethnocultural Diversity in Canada report (Statistics

Canada, 2014) states that

20.6% of the total population is foreign born and that 19.1% are visible

minorities. The three largest minority groups are South Asians, Chinese, and

Blacks. Statistics Canada also projects that close to 30% of the nation’s population

will consist of visible minorities by 2031, including both foreign-born and

Canada-born visible minorities (Statistics

Canada, 2010). Does our

profession reflect this current demographic? The 8Rs Study (Ingles et al.,

2005) states that

visible minorities “are under-represented across all types of libraries” and

make up “only 7% of the library professional librarian labour force” (compared

to 14% of Canada’s entire labour force).

It

was ViMLoC’s intention to learn directly from visible minority librarians

first, about the number of them working in Canadian institutions and second,

through an open-ended question, their professional needs, challenges, and

barriers, so that ViMLoC can partner with CLA and other interested entities and

collaborate to assess, plan, and implement the needed frameworks to work with

these librarians and address their concerns.

Knowing

the number of librarians and their needs will help ViMLoC create pathways and

partnerships to address their needs, find ways to eliminate barriers, provide

ways to network, and create a mentorship program. Gathering statistical

evidence was the first step towards achieving ViMLoC’s aims to help visible

minority librarians receive professional support and network. Armed with this

data, ViMLoC representatives can make a case to libraries and library schools

in Canada to work with ViMLoC to design and initiate programs to help visible

minority librarians achieve ALA accreditation, progress faster in their

careers, and become employable sooner, and also work with professional

organizations to request funding to support their education and enable them to

attend conferences. If ViMLoC continues gathering these statistics every 3-5

years, the change in the data will help them understand the rate at which this

population number is changing, the reasons for such a change, the immigration

patterns of this group (where they come from), and how ViMLoC can help or

support this particular group.

Literature

review

A

literature review was conducted to ascertain if there were any similar studies

done among visible minority librarians. None were found. The literature review

was expanded to find any material on visible minority librarians and their

experiences. There is a dearth of literature in Canada that focuses on the

challenges and barriers faced and overcome by visible minority librarians. A

search in Library and Information Science Abstracts (LISA) and Library

Literature and Information Science Full Text & Retrospective limited to

Canadian publications retrieves very few results. There are career and

demographic profiles of librarians that also feature minority librarian data (Fox, 2007; Ingles et al.,

2005; McKenna,

2007), papers on the

importance of diversity among Canadian librarians (Kandiuk, 2014; Leong, 2013), papers on

multicultural populations, services, and collections (Berry, 2008; Chilana, 2001; Cho & Con, 2012; Dilevko &

Dali, 2002; Kumaran & Salt, 2010;

Paola Picco, 2008), and articles

on information seeking behaviour or information practices of immigrants (Caidi, 2008; Caidi & MacDonald, 2008; Hakim Silvio, 2006) and reading

practices of Canadian immigrants (Dali, 2012).

There

are very few scholarly works that speak directly about librarians who are

visible minorities and their experiences as Canadian librarians, except for the

recent publications on leadership (or lack thereof) among minority librarians (Kumaran, 2012) and the

collection of chapters co-edited by Lee and Kumaran (2014), which includes

papers on experiences of going through the tenure process (Majekodunmi,

2014); struggles and

success stories of assimilating themselves into the Canadian library system (Dakshinamurti,

2014; Lau,

2014; Li,

2014; Maestro,

2014; Shrivatsava,

2014); challenges

specifically as Chinese born or Chinese-Canadian librarians (Li, 2014; Cho,

2014); and struggles as new immigrants in this new country (Gupta, 2014;

Kumaran, 2014).

A

major challenge in finding and accessing information about these librarians

lies in the fact that there is no universally accepted terminology or subject

heading by which these librarians can be identified (Aspinall, 2002). Various terms

such as “ethnic minorities,” “visible minorities,” “diverse librarians,” and

“librarians of colour” are used to identify this group of librarians. Adding to

the confusion is the United Nations’ request to Canada to not use the term

“visible minorities” as it is considered racist terminology (Government of

Canada, 2011; National Post, 2007).

Lack

of literature on and by minority librarians in Canada themselves could be due

to many reasons: they are in positions that do not require them to publish;

lack of training in writing academic papers, especially if they are first

generation minority librarians; lack of support for writing for publication;

lack of time or funding; not having a dedicated Canadian library journal that allows

them to voice their thoughts; and perhaps fear of bringing attention to

themselves by expressing their opinions.

Methodology

An

online survey questionnaire was created using FluidSurvey (see Appendix 1:

Questionnaire). After ethics approvals from the authors’ respective

institutions, the survey was made available between December 9, 2013 and

January 31, 2014. It was a nation-wide survey with participation from visible

minority librarians working in Canadian institutions both within and outside of

Canada. The online survey invitation was sent to visible minority librarians

through relevant library association electronic mail lists, such as the

Canadian Library Association, Canadian Medical Libraries Interest Group, and

Special Libraries Association. The invitation was also posted on ViMLoC’s

electronic mail list and website.

The

survey consisted of 12 questions: multiple-choice, yes/no, and open-ended. The

survey provided a definition of visible minorities as defined by the Canadian

Employment Equity Act (Government of

Canada, 2014) and asked if

the participant was a visible minority librarian. If the response was “No,” the

survey closed. Respondents who did not identify themselves as minority

librarians were excluded from completing the survey. The rest of the survey was

divided into personal and professional questions.

Results

Of

the 192 individuals that attempted, 120 who identified themselves as visible

minority librarians were permitted by the system to complete the survey.

Once

participants identified themselves as visible minorities, they were asked to

identify which ethnic groups they belong to or which group fits them best, with

options provided. Over 36% of the respondents identified themselves as Chinese,

followed by South Asian and Black. While many of the respondents for the

“other” category identified themselves as “mixed race,” one respondent

identified as “Canadian.” It is possible that this respondent is a second or

third generation Canadian and does not identify with any other groups offered

as options.

Question:

What group do you belong to or which group fits you the best?

Participants

were also asked if they were first or second generation Canadians. (First

generation visible minority would mean that they were born elsewhere and moved

to Canada at some point during their lives. Second generation would mean they

were born in Canada to immigrant parents.) Of the librarians who completed the

survey, 63% identified themselves as first generation visible minorities and

28% identified themselves as second generation. Another 9% of them identified

themselves under the “other” category. Comments from “other” included “one

parent was an immigrant to Canada,” “third generation,” “yonsei” (fourth

generation Japanese Canadian) and “US permanent resident born to second

generation Americans.”

Table

1

Ethnic

Groups

|

Chinese |

36% |

43 |

|

South

Asian (includes Bangladeshi, Indian, Sri Lankan) |

20% |

24 |

|

Black |

12% |

15 |

|

Filipino |

3% |

4 |

|

Latin

American |

1% |

1 |

|

South

East Asian (includes Vietnamese, Cambodian, Malaysian and Laotian) |

2% |

3 |

|

Arab

(includes Egyptian, Kuwaiti and Libyan) |

2% |

2 |

|

West

Asian (includes Afghan, Assyrian and Iranian) |

5% |

6 |

|

Korean |

1% |

1 |

|

Japanese |

6% |

7 |

|

Other,

please specify... |

12% |

14 |

Table

2

Generation

|

First

generation |

63% |

76 |

|

Second

generation |

28% |

33 |

|

Other |

9% |

11 |

Table

3

Where

Library Degree Was Received

Space

was provided for respondents to provide further information if they wanted to:

the year in which they came to Canada or their age when they came to Canada.

There were a few who came to Canada in or after 2000 (N=7), a few who came in

the 70s, 80s and 90s (N=7), some who came before they were 11 years old (N=6),

and the rest identified themselves as second, third or fourth generation

Canadians.

The

next questions focused on educational and professional accomplishments and

status, particularly where participants received their professional library

degree; whether it was ALA accredited; the province where they currently work;

number of hours they work per week; and the type of institution where they

work.

When

asked if they completed their library degree in Canada, 84% responded “Yes” and

19% responded “No.” When asked to reveal from which university or college they

received their library professional degree, only 101 out of 120 responded. It

is possible that some respondents were still in library school or simply did

not want to identify where they received their degrees for unknown reasons.

Almost 40% of the 101 respondents stated that they had graduated from the

University of British Columbia, Vancouver, British Columbia, followed by the

University of Western Ontario, London, Ontario, at 31%. Of the 19 respondents

who indicated that they had foreign degrees, 7 respondents had received their degrees

in Africa and Asia (outside of United Kingdom and United States), but only 3

identified their degrees as non-ALA accredited.

When

asked what types of library they were employed in, an equal number of

respondents identified themselves as working in public and academic libraries

(38% each), followed by special libraries (15%). Those who chose “other”

identified themselves as “unemployed,” “library consultant with provincial

government,” “federal agency,” or “federal government.”

The

authors wanted to know how widely these minority librarians were spread across

Canada and beyond. The table below indicates that although they are spread out

all over Canada and beyond, a vast majority of them are in British Columbia and

Ontario.

This

is not surprising because these two provinces have the highest numbers of

immigrant populations, as illustrated in the table below (Statistics

Canada, 2009).

The

authors used a list of job categories from the American Library Association’s

(ALA) website (accessible only to its members) with some modifications for the

creation of the next question about types of jobs in which these librarians

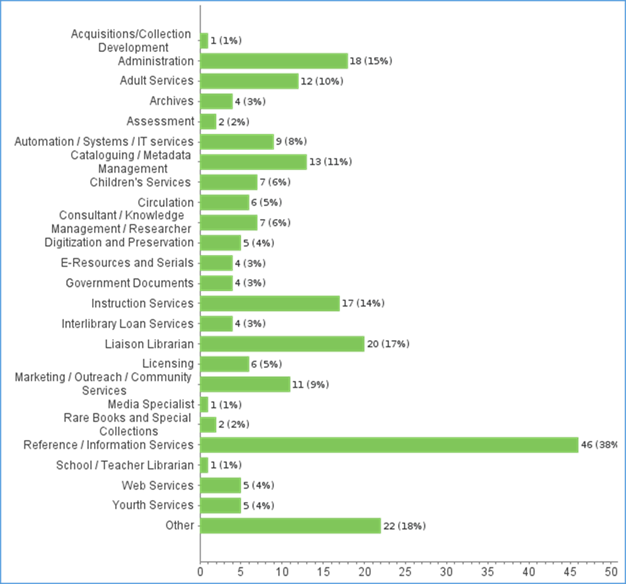

were employed. When asked to identify themselves to the closest job category(ies), 38 % identified themselves as

reference/information services librarians, followed by “other” (18%) and

“administration” (15%). The authors did not ask what “other” meant in this

category and it is also not clear what types of administrative positions these

respondents hold.

Table

4

Employment

by Library Type

|

Public

Library |

38% |

46 |

|

Regional

Library |

1% |

1 |

|

Academic

Library |

38% |

45 |

|

Special

Library |

15% |

18 |

|

School

Library |

1% |

1 |

|

In

Library school |

2% |

2 |

|

Other

- please specify |

6% |

7 |

Table

5

Geographic

Distribution

|

Alberta |

8% |

10 |

|

British

Columbia |

40% |

48 |

|

Manitoba |

6% |

7 |

|

New

Brunswick |

2% |

2 |

|

Newfoundland

and Labrador |

1% |

1 |

|

Nova

Scotia |

5% |

6 |

|

Nunavut |

1% |

1 |

|

Ontario |

27% |

32 |

|

Quebec |

4% |

5 |

|

Saskatchewan |

6% |

7 |

|

Other

(if you are working for a Canadian Library outside of the country) |

1% |

1 |

Table

6

Visible

Minority population, by province and territory (2006 Census)

|

|

Canada |

Que. |

Ont. |

Man. |

Sask. |

|

Alta. |

B.C. |

|

Total

Population |

31,241,030 |

7,435,900 |

12,028,895 |

1,133,515 |

953,850 |

|

3,256,355 |

4,074,380 |

|

Total

visible minority population |

5,068,095 |

654,350 |

2,745,205 |

109,100 |

33,895 |

|

454,200 |

1,008,855 |

|

South

Asian |

1,262,865 |

72,850 |

794,170 |

16,565 |

5,130 |

|

103,885 |

262,290 |

|

Chinese |

1,216,565 |

79,825 |

576,980 |

13,705 |

9,505 |

|

120,270 |

407,225 |

|

Black |

783,795 |

188,070 |

473,765 |

15,660 |

5,090 |

|

47,075 |

28,315 |

|

Filipino |

410,700 |

24,200 |

203,220 |

37,785 |

3,770 |

|

51,090 |

88,075 |

|

Latin

American |

304,245 |

89,510 |

147,135 |

6,275 |

2,520 |

|

27,265 |

28,960 |

|

Arab |

265,550 |

109,020 |

111,405 |

2,320 |

1,710 |

|

26,180 |

8,635 |

|

Southeast

Asian |

239,935 |

50,460 |

110,045 |

5,670 |

2,555 |

|

28,605 |

40,690 |

|

West

Asian |

156,695 |

16,115 |

96,615 |

1,960 |

1,020 |

|

9,655 |

29,810 |

|

Korean |

141,890 |

5,310 |

69,540 |

2,190 |

735 |

|

12,045 |

50,490 |

|

Multiple

visible minority |

133,120 |

11,310 |

77,405 |

3,265 |

810 |

|

13,250 |

25,415 |

|

Japanese |

81,300 |

3,540 |

28,080 |

2,010 |

645 |

|

11,030 |

35,060 |

|

Visible

minority, not included elsewhere |

71,420 |

4,155 |

56,845 |

1,690 |

405 |

|

3,850 |

3,880 |

When

asked if they worked part-time (less than 30 hours/week), full-time (30 or more

hours/week) or casual hours, an overwhelming 82% responded that they worked

full time. The number of hours for part-time and full-time were derived from

Statistics Canada (2012b).

Those

who chose “other” responded that they were “unemployed,” “volunteering,” “part

time contract,” or “casual.”

At

the panel presentation at the Ontario Library Association Super Conference,

attending visible minority librarians mentioned that they faced various

challenges. In light of this, our final question was an open-ended question

that asked them to provide information on anything they deemed relevant to

visible minority librarians. Of the 120 participants, 50 (47%) responded to

this question.

The

open-ended question at the end of the survey helped elicit more information on

these challenges. The question was “Please use the box below to comment on

anything else - topics could be on the challenges of finding the right job, the

need for another degree, lack of support through mentorship or networking

possibilities, etc.” Below is a list of selected open-ended responses:

“Networking and

mentoring among minorities is lacking in the field but something is needed.”

“There is

definitely a lack of support and lack of any access to information on how to

succeed as a visible minority librarian in Canada. Am glad that VimLoC is

changing that.”

Table

7

Type

of Work

Table

8

Hours

Worked

|

Part time |

9% |

11 |

|

Full time |

82% |

99 |

|

Casual hours |

5% |

6 |

|

Other |

3% |

4 |

“Looking forward to a time when upper management reflects the diversity

of Canada.”

“There is definite lack of mentoring for new and early career

librarians, for both those of minority status and non-minorities.”

“I think that

having a professional group within CLA dedicated to visible minorities is quite

important as it gives us an opportunity to discuss issues not often confronted

by our majority counterparts. “

“Lack of

cultural diversity and inclusive practices in the workplace, particularly at

the leadership levels.”

“No programs

encouraging/assisting minorities in Library studies.”

“Lack of

leadership opportunities.”

The challenge of

moving up the career ladder.”

“I think the

professional as a whole lacks visible minority presence at all levels of the

organization.”

“My working experience in Canada has been rewarding. There was great

support but I would certainly advocate for a stronger presence of minority

librarians in all aspects of the library communities in Canada.”

“It's important

for librarians new to Canada to learn the culture and norms here. Their

experience and qualifications do not always translate easily and the onus is on

them to get up to speed. Employers should also recognize talent and potential

and be willing to take a chance on librarians new to the country.”

“Lack of

experience and opportunities to gain library experience is one of the biggest

challenges.”

Some

of the broad themes that evolved through the qualitative analysis of the

open-ended question are: jobs, mentorship, professional development courses,

workplace issues, general barriers, and success stories.

In

the job category, respondents stated that they don’t believe visible minorities

are being hired in considerable numbers in spite of being encouraged to apply.

Some have problems designing their CV or resume according to Canadian

standards. Finding the first job was often the biggest challenge. When speaking

of their own workplaces, there were positive and negative comments. There was

mention of lack of diversity at their own workplaces, where subtle ways of

stereotyping and alienating exist. They speak of being passed over for

promotions and being told that they do not have Canadian work experience. There

are cases where patrons ignore the visible minority librarian and seek out a

Caucasian librarian. There are others who have not experienced any of these

issues and continue to have successful careers.

In

the mentorship category, responses reiterated the lack of mentorship and

networking opportunities with other minorities in Canada. Participants stated

that they use the American networking opportunities.

There

were suggestions that visible minority librarians take courses on client engagement,

customer service skills, writing reports, special collections (unique language

collections), project management, social media tools, human resources, and

budgeting or financial management.

Minority

librarians in managerial or supervisory roles have identified some issues they

perceive as barriers among other minority librarians in order to succeed in

their careers. The barriers they have observed among fellow minority librarians

are lack of communication skills, lack of customer service skills, and lack of

knowledge of the Canadian work environment. It was also noted that some of

these minority librarians are not willing to accept feedback.

Other

barriers that respondents noted are lack of an initiative to recruit more

minority students at library schools, evaluation of credentials, lack of role

models, and lack of leadership courses for minorities.

Key Findings and

Conclusions

This

is a landmark study capturing a snapshot of the demographics of visible

minority librarians working for Canadian institutions. The authors hope that

the findings of this study will help set future strategic directions of

ViMLoC.

As

evidence from our survey suggests, there are at least 120 first, second and

other generation minority librarians working in (or for) Canadian institutions

across the country and beyond. They work in different kinds of libraries, are

spread out all over Canada, and have had their library education in various

countries or in Canada. Many of the respondents have reiterated what ViMLoC learned

at OLA in 2013 – that they need a forum to discuss their issues, a mentorship

program to seek advice from other librarians with similar backgrounds who have

been in similar situations to themselves when finding jobs or re-pursuing their

professional library degrees, and to have networking opportunities.

It

was interesting to note that a majority of the respondents graduated from

either the University of British Columbia (UBC) or the University of Western

Ontario (UWO). There may be many reasons for this: more immigrants living in

these two provinces, easier admission requirements, larger cohort sizes, higher

intake per year, the option to earn a degree faster through a one year program,

and others. It would be beneficial for ViMLoC to explore this further in future

iterations of a similar survey to see if there is consistency in this data. If

the trend to enroll at UBC or UWO continues to stay higher, this will be an

opportunity for ViMLoC to partner with CLA to initiate conversations with these

schools encouraging them to work with ALA and minority librarians to find ways

to accredit their foreign degrees, so these librarians can be employable sooner

than later.

The

ViMLoC mentoring program is already underway, and ViMLoC hopes to work with the

CLA and ViMLoC members to address scholarship and leadership training

possibilities. CLA needs to consider offering many of these training sessions

free of charge through their online forum, the Educational Institute. These

topics are often covered in library schools, but for first generation

librarians who did not attend library schools in Canada and are not yet

employed in a library, these free workshops will be particularly

beneficial.

Many

librarians have expressed a need for networking opportunities. Although ViMLoC

has been active in professional conferences, such as CLA and OLA, and has a

website, Facebook page, LinkedIn page and a Google electronic mail list,

through which members can interact with each other, an interest in creating

other networking opportunities still remains.

Limitations and

Recommendations

Although

the survey was sent out to various electronic mail lists, it is possible that

there were librarians who did not take the time to complete the survey. Due to

financial constraints some minority librarians may not be members of any of the

library associations, and due to lack of awareness first generation librarians

may not be part of library electronic mail lists. These members may have been

missed in the survey. Unfortunately, there is no way to know the number of

visible minority librarians that did not take the survey.

This

survey is also only a snapshot in time and these demographics are likely to

change with changes in government policies on immigration. ViMLoC should aim to

conduct these surveys every 3-5 years to compare statistics and learn more

about demographic changes, the needs of this population, their challenges and

barriers, and their continuous evolution in the library field. Data from this survey

will help ViMLoC to find and implement ways to create better networking

opportunities for visible minority librarians to connect, collaborate, and

create a sense of community.

It

will also be beneficial for ViMLoC to learn from this group of librarians the

types of administrative positions they hold and what “other” positions they

hold in their libraries, as well as to learn more about their leadership

experiences, trials, and successes.

ViMLoC

should consider collaborating with CLA and its Education Institute more closely

so both entities can be proactive in helping this group of visible minority

librarians.

Another

initiative for ViMLoC to consider is establishing connections with Canadian

library schools and partnering with them to identify and recruit minorities in

the community to join their schools.

While

ViMLoC has initiated and worked on various projects, funding is always an issue

for this group of librarians, especially if they are first generation

immigrants from Asian and African countries. All ViMLoC representatives are

volunteers interested in this topic and have worked hard on many of the

initiatives mentioned. Funding help from CLA will go a long way in supporting

this network that can help these librarians, particularly those not yet

employed. Apart from helping ViMLoC to offer free web-based workshops on

various topics addressed previously, CLA funding can be used to attract visible

minorities to join library schools and attend library conferences.

Future

surveys undertaken by ViMLoC should not only collect quantitative data, but

also gather more qualitative responses. These qualitative responses will assist

in setting further strategic directions for ViMLoC.

Acknowledgements

The

authors would like to thank CLA for its sponsorship of one-year free personal

CLA membership to one of the lucky respondents of the survey.

The

authors would also like to thank Lyn Currie (retired librarian, University of

Saskatchewan) and Norda Majekodunmi (York University) for taking the time to

read previous versions of the manuscript and offer suggestions for

improvement.

References

Aspinall, P. J. (2002). Collective terminology to describe the minority

ethnic population: The persistence of confusion and ambiguity in usage.

Sociology, 36(4), 803-816. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/003803850203600401

Berry, E. (2008). Multicultural services in Canadian public libraries.

Bibliothek Forschung und Praxis, 32(2), 237 - 242. http://dx.doi.org/10.1515/bfup.2008.036

Caidi, N. (2008). Information practices of ethno-cultural communities

(IPEC). Toronto, ON, CAN: CERIS - The Ontario Metropolis Centre. Retrieved from

http://ceris.metropolis.net/Virtual%20Library/RFPReports/CaidiAllard2005.pdf

Caidi, N., & MacDonald, S. (2008). Information practices of Canadian

Muslims post-9/11. Toronto, ON, CAN: CERIS - The Ontario Metropolis Centre.

Chilana, R. S. (2001). Delivering multilingual services in public libraries

in British Columbia. PNLA Quarterly, 65(3), 18-20.

Cho, A. (2014). Diversity pathways in librarianship: Some challenges

faced and lessons learned as a Canadian-born Chinese male librarian. In D. Lee

& M. Kumaran (Eds.), Aboriginal and visible minority librarians: Oral

histories from Canada (pp. 89-102). Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow.

Cho, A., & Con, A. (2012). Partnerships linking cultures:

Multicultural librarianship in British Columbia’s public libraries. In C. B.

Smallwood & K. Becnel (Eds.), Library services for multicultural patrons:

Strategies to encourage library use (p. 338). Lanham, MD: Scarecrow Press.

Dakshinamurti, G. B. (2014). Reflections on my experience in Manitoba as

a visible minority librarian: A personal perspective and review of future

challenges for visible minority librarians. In D. Lee & M. Kumaran (Eds.),

Aboriginal and visible minority librarians: Oral histories from Canada (pp.

17-26). Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow.

Dali, K. (2012). Reading their way through immigration: The leisure

reading practices of Russian-speaking immigrants in Canada. Library &

Information Science Research, 34(3), 197-211. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.lisr.2012.02.004

Dilevko, J., & Dali, K. (2002). The challenge of building

multilingual collections in Canadian public libraries. Library Resources &

Technical Services, 46(4), 116-137.

Fox, D. (2007). A demographic and career profile of Canadian research

university librarians. The Journal of Academic Librarianship, 33(5), 540-550. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2007.05.006

Government of Canada. (2011). International convention on the

elimination of all forms of racial discrimination: 19th and 20th reports of

Canada. Retrieved from http://www.canadianheritage.gc.ca/DAMAssetPub/DAM-drtPrs-humRts/STAGING/texte-text/19-20_1362690863117_eng.pdf?WT.contentAuthority=3.1

Government of Canada. (2014). Employment equity act. Retrieved from http://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/acts/E-5.401/page-1.html

Gupta, A. (2014). A minority librarian's journey: Challenges and issues

along the way. In D. Lee & M. Kumaran (Eds.), Aboriginal and visible

minority librarians: Oral histories from Canada (pp. 147-155). Lanham,

Maryland: Scarecrow.

Hakim Silvio, D. (2006). The information needs and information seeking

behaviour of immigrant southern Sudanese youth in the city of London, Ontario:

an exploratory study. Library Review, 55(4), 259-266. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/00242530610660807

Ingles, E., De Long, K., Humphrey, C., Sivak, A., Sorensen, M., & de

Peuter, J. (2005). The 8Rs research team. Canadian Library Human Resource

Study. Retrieved from http://www.ls.ualberta.ca/8rs/8RsFutureofHRLibraries.pdf

Kandiuk, M. (2014). Promoting racial and ethnic diversity among Canadian

academic librarians. College & Research Libraries, 75(4), 492-556. http://dx.doi.org/10.5860/crl.75.4.492

Kumaran, M. (2012). Leadership in libraries: A focus on ethnic-minority

librarians. Oxford, UK: Chandros Publishing.

Kumaran, M. (2014). The immigrant librarian: challenges big and small.

In D. Lee & M. Kumaran (Eds.), Aboriginal and visible minority librarians:

Oral histories from Canada (pp. 171-184). Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow.

Kumaran, M., & Salt, L. (2010). Diverse populations in Saskatchewan:

The challenges of reaching them. Partnership: The Canadian Journal of Library

& Information Practice & Research, 5(1), 1-25.

Lau, K. E. (2014). Becoming the Rhizome: Empowering librarians and

archivists of color. In D. Lee & M. Kumaran (Eds.), Aboriginal and visible

minority librarians: Oral histories from Canada (pp. 123-134). Lanham,

Maryland: Scarecrow.

Lee, D., & Kumaran, M. (2014). Aboriginal and visible minority

librarians: Oral histories from Canada. Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow.

Leong, J. H. T. (2013). Ethnic diversity at the University of Toronto

Libraries. Paper presented at the International Federation of Library

Associations (IFLA), Singapore. Retrieved from http://library.ifla.org/67/

Li, L. (2014). From China to Canada: Experiences of a college librarian

in the Canadian prairies. In D. Lee & M. Kumaran (Eds.), Aboriginal and

visible minority librarians: Oral histories from Canada (pp. 49-56). Lanham,

Maryland: Scarecrow.

Maestro, E. (2014). Proud to be a Filipino librarian. In D. Lee & M.

Kumaran (Eds.), Aboriginal and visible minority librarians: Oral histories from

Canada (pp. 27-36). Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow.

Majekodunmi, N. (2014). From recruitment to tenure: A reflectionon race

and culture in a Canadian acadmiec library. In D. Lee & M. Kumaran (Eds.),

Aboriginal and visible minority librarians: Oral histories from Canada (pp.

199-211). Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow.

McKenna, J. (2007). Canadian library human resources short-term supply and

demand crisis is averted, but a significant long-term crisis must be addressed.

Evidence Based Library and Information Practice, 2(1), 121-127.

National Post. (2007). Canada told not to use term 'visible minorities.'

National Post. Retrieved from http://www.nationalpost.com/news/story.html?id=99f7e1e1-4424-429c-908a-125822989a97&k=18408

Paola Picco, M. A. (2008). Multicultural libraries' services and social

integration: The case of public libraries in Montreal Canada. Public Library

Quarterly, 27(1), 41-56. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01616840802122443

Shrivatsava, A. (2014). Observations of a new immigrant library

professional: Career journey from India to Canada via the Netherlands. In D.

Lee & M. Kumaran (Eds.), Aboriginal and visible minority librarians: Oral

histories from Canada (pp. 103-116). Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow.

Statistics Canada. (2009). Visible minority population, by province and

territory (table). 2006 Census. Retrieved from http://www.statcan.gc.ca/tables-tableaux/sum-som/l01/cst01/demo52a-eng.htm

Statistics Canada. (2010, March 9). Study: Projections of the diversity

of the Canadian population. The Daily. Retrieved from http://www.statcan.gc.ca/daily-quotidien/100309/dq100309a-eng.htm

Statistics Canada. (2012a). Visible minority of person. Retrieved from http://www.statcan.gc.ca/concepts/definitions/minority-minorite1-eng.htm

Statistics Canada. (2012b). Classification of full-time and part-time

work hours. Retrieved from http://www.statcan.gc.ca/concepts/definitions/labour-travail-class03b-eng.htm

Statistics Canada. (2013). Visible minority and population group

reference guide. National household survey, 2011. Statistics Canada Catalogue

no. 99-010-XWE2011009. Retrieved from http://www12.statcan.gc.ca/nhs-enm/2011/ref/guides/99-010-x/99-010-x2011009-eng.cfm

Statistics Canada. (2014). Immigration and ethnocultural diversity in

Canada. Statistics Canada Analytical Document 99-010-X. Retrieved from http://www12.statcan.gc.ca/nhs-enm/2011/as-sa/99-010-x/99-010-x2011001-eng.cfm

ViMLoC. (2014). About us. Retrieved from

http://vimloc.wordpress.com/terms-of-reference/

Appendix

Survey of Visible Minority

Librarians Statistics in Canada

Page 1

Project Title: Collecting

Statistics of Visible Minority Librarians in Canada

Researcher(s): Maha Kumaran

(Liaison, McGill University) are current co-moderators and founding members of

the Visible Minority Librarians of Canada (ViMLoC) Network, Canadian Library Association

(2011-2013).

Compensation: This survey will take about 5 minutes to complete. By

participating in the survey you will have a chance to win a one-year free

personal membership to CLA. If you would like to enter your name for this draw,

please make sure you enter the information as necessary when redirected at the

end of the survey. Your chance of winning is estimated at approximately 1%,

depending on the actual number of participants who entered their names into the

draw.

Purpose and Objective: Currently there

is no data on the number of visible minority librarians working in Canadian

libraries. The Visible Minority Librarians of Canada (ViMLoC) Network wants to

gather statistics on the number of visible minority librarians working in or

for Canadian Libraries. The results of this survey will serve as foundational

data that will help ViMLoC identify the needs of visible minority librarians

and propose projects or initiatives to empower them in their current positions

or their future career development initiatives.

Research

Background: According to Statistics Canada, the current visible

minority population in Canada is over 6 million. This is 19.1% of Canada’s

total population[1].

Statistics Canada also projects that close to 30% of the nation’s population

will consist of visible minorities by 2031 that will include both foreign-born

and Canadian born visible minorities[2].

Does our current profession reflect this demographic? The 8Rs Study states that visible minorities

“are under-represented across all types of libraries” and make up “only 7%

library professional librarian labour force (compared to 14% of Canada’s entire

labour force)[3].

With this survey, ViMLoC intends to determine the number of visible minority

librarians in Canadian libraries. The information collected through this survey

will serve as foundational data that enables ViMLoC to identify the needs of

this particular group of librarians.

The Canadian Employment Equity Act defines visible

minorities as "persons, other than Aboriginal peoples, who are

non-Caucasian in race or non-white in colour.[4]"

The visible minority population consists mainly of the following groups:

Chinese, South Asian, Black, Arab, West Asian, Filipino, Southeast Asian, Latin

American, Japanese and Korean.

Confidentiality: All data

collected will be maintained, managed and stored by the two researchers. After

you complete the survey, you will be redirected to another form to provide your

personal information for the draw to win a personal one-year CLA membership.

The survey is set up so that researchers will not be able to associate the

personal information with the rest of the data.

Right to Withdraw: Your

participation in this survey is voluntary. You may withdraw from this survey

any time by closing the browser. Once all the information is entered and

submitted, the data is anonymous and withdrawal will not be possible.

Follow up: The researchers

intend to publish the survey results of this study through a Canadian open

access journal, such as The Partnership Journal, and if you are interested, you

will be sent a link to this publication. If you would like to know the results

of the study prior to publication, please contact either one of the

researchers.

Questions or Concerns: This project

has been approved on ethical grounds by the University of Saskatchewan and

McGill University. If you have any questions or concerns regarding your rights

or welfare as a participant in this research study, please contact the

University of Saskatchewan Research Ethics Office at 306-966-2084 or ethics.office@usask.ca or the Manager, Research Ethics, McGill University at

514-398-6831 or lynda.mcneil@mcgill.ca. By completing and submitting this survey, YOUR FREE AND INFORMED

CONSENT is implied.

If you have any questions, please contact: Maha at maha.kumaran@usask.ca or Heather at heather.cai@mcgill.ca.

On the next page, you will see a PDF/Word icon. Please

use this icon to print and save a copy of the consent form if you need it for

your records.

Page 2

The Canadian Employment

Equity Act defines visible minorities as "persons, other than Aboriginal

peoples, who are non-Caucasian in race or non-white in colour." The

visible minority population consists mainly of the following groups: Chinese,

South Asian, Black, Arab, West Asian, Filipino, Southeast Asian, Latin

American, Japanese and Korean. Are you a visible minority librarian currently

working in Canada?

Yes

No

What group do you belong to

or which group fits you the best?

Chinese

South Asian (Includes Bangladeshi, Indian, Pakistani, SriLankan)

Black

Filipino

Latin American

South East Asian (includes Vietnamese, Cambodian, Malaysian, and Laotian)

Arab (includes Egyptian, Kuwaiti and Libyan)

West Asian (Includes Afghan, Assyrian and Iranian)

Korean

Japanese

Other (please specify) ________________________

Tell us if you are a first

generation minority librarian or not. First generation would mean that you were

born else where but moved to Canada at some point in your life. Second

generation would mean you were born in Canada to immigrant parents. If you

would like to add an explanation about this, please use the text box beside,

such as your age or the year when you came to Canada.

|

|

First generation ______________________ |

|

|

|

Second generation

______________________ |

|

|

|

Other ______________________ |

Did you complete your

professional library degree in Canada?

Yes

No

If no, tell us which country

you completed your professional degree?

![]()

Was the professional library

degree considered ALA accredited?

![]()

If yes, tell us which

University /College you received your ALA accredited library degree.

![]()

What type of library are you

currently working at? If you are at a special library, please specify the type

of library - Government, Religious Organization, etc.

Public

Library

Regional Library

Academic Library

College Library

Special Library ______________________________

School Library

Other (please specify)

Which province / territory

do you currently work in?

Alberta

British Columbia

Manitoba

New Brunswick

Newfoundland and Labrador

Northwest Territories

Nova Scotia

Nunavut

Ontario

Prince Edward Island

Quebec

Saskatchewan

Yukon

Other (if you are working for a Canadian Library outside of Canada)

___________________

Select the job category(ies)

that matches your current job responsibilities

Acquisitions

/ Collection Development

Administration

Adult Services

Archives

Assessment

Automation / Systems / IT Services

Cataloging / Metadata Management

Children’s Services

Circulation

Consultant / Knowledge Management/ Researchers

Digitization and Preservation

E-Resources and Serials

Government Documents

Instruction Services

Interlibrary Loan Services

Liaison Librarian

Licensing

Marketing/Outreach/Community Services

Media Specialist

Rare Books and Special Collections

Reference / Information Services

School / Teacher Librarian

Web Services

Youth Services

Other (Please Specify) _______________________

Do you work part-time (less

than 30 hours/week), full-time (30 or more hours/week), or casual hours? Please indicate below:

Part Time

Full Time

Casual Hours

Other _________________________________

Please use the box below to

comment on anything else: topics could be on the challenges of finding the

right job, the need for another degree, lack of support through mentorship or

networking possibilities, etc.

![]()

If you would like to save a copy of the survey for your own records

please click on the PDF/Word icon below now.

CLA one year personal membership draw: This is optional, if you do not

want to enter the information click Submit.

Your

full name: ![]()

Your

institution: ![]()

Your

mailing address with postal code: ![]()

Your

email: ![]()

Your

day time phone number: ![]()

Thank

you for taking the time to complete this survey.