Introduction

Phrases

such as library jargon, library terminology, and library vocabulary evoke references to

services and objects, such as circulation desks, monographs, and reserves. Much

has been written about librarians’ efforts to help patrons understand this

language (Adedibu & Ajala, 2011; Ayre,

Smith, & Cleeve, 2006; Chaudhry & Choo, 2001; Dewey, 1999;

Doran, 1998; Foster, 2010; Houdyshell, 1998; Hutcherson, 2004; Imler &

Eichelberger, 2014; Naismith & Stein, 1989; Pinto, Cordon, & Gómez

Diaz, 2010; Sonsteby & DeJonghe, 2013; Spivey, 2000; Swanson & Green,

2011). Rather than alluding to tangible objects and services, information literacy jargon, on the

other hand, may elicit abstract thoughts and actions that require a

higher-degree of critical thinking to comprehend and apply (Pinto, Cordon,

& Gómez Diaz, 2010). Possibly due to time

limitations or misconceptions of students’ prior knowledge, librarians can

easily overwhelm first-year composition students with this terminology during

library instruction classes. For instance, in a “source evaluation” session, a librarian might hand

students a checklist that describes evaluative criteria such as authority, accuracy, currency, purpose, relevancy, objectivity/bias,

among others. In addition to exposing students to this laundry list of terms,

checklists neglect the complexities and nuances of source evaluation; they fail

to consider information need and encourage a dichotomous assessment of

information (Benjas-Small, Archer, Tucker, Vassady, & Resor Whicker, 2013;

Burkholder, 2010; Meola, 2004). This “checklist” approach has been under

increased scrutiny since the creation of the ACRL Framework for Information Literacy (Association of College

& Research Libraries, 2015). The Framework

encourages a more holistic and authentic pedagogy which focuses on the

information-creation process, and how this process affects credibility and the

appropriateness of a source. Despite this gradual departure from “checklists,”

librarians continue to use the same or similar words to teach evaluation

skills, and students must still understand the meanings and usages of such

terms as authority, purpose, and bias.

The casual

blending of librarians’ language with that of composition instructors can

further confuse a discussion on source evaluation. In a one-shot library

session, librarians tend to approach source evaluation as locating and identifying

a “credible” source that meets the students’ information needs. Librarians

teach students to evaluate a source’s authority, purpose, audience, and so

forth. A first-year composition instructor might concur with this pedagogy, but

could have different ideas of what makes a source “credible”, “reliable,”

“reputable,” etc., than that of the librarian. Further, instructors view source

evaluation through the lens of rhetorical analysis – a concept that requires

students to evaluate the author’s argument,

in addition to the credibility of the source from which it is found (Mazziotti

& Grettano, 2011). Students must consider authors’ logic, persuasiveness,

and ethos. These subtle distinctions in purposes may not be obvious to

librarian and instructor, and this oversight can spill over into their use of

language in the classroom. Through the examination of students’ written work,

the authors of this paper – an instruction librarian and an instructor of

first-year composition – illustrate how inconsistencies in language-use and

meaning between these two groups can negatively affect student learning. We

consider the development of a common vocabulary as a possible solution.

Background

Auburn

University is a land, sea, and space grant university in east Alabama with an

enrollment of approximately 26,000 students. The English composition program

serves about 4,000 undergraduate students in nearly 250 classes each fall and

spring. ENGL1100 is the introductory course on academic reading and writing and

focuses on the development of writing processes and rhetorical awareness of

audience and style. Taking up the writing skills from ENGL1100, ENGL1120

emphasizes argumentative writing and academic research that requires library

instruction sessions. ENGL1120 is based on a scaffolded curriculum, in which

students write several shorter essays throughout the semester, culminating in a

final research paper. Each ENGL1120 class takes part in 2 to 3 library

sessions, which make up the bulk of the 600-700 information literacy classes

taught each year by the university librarians. This is also where the majority

of assessment for the core curriculum’s information literacy student learning

outcome occurs. Sessions concentrate on basic information literacy concepts

such as keyword development, search strategies, and source evaluation.

Literature

Review

Collaborations

between librarians and composition instructors, the inherent relationship

between information literacy and writing, and the concept of information

literacy as a situated literacy within composition have all received

substantial coverage in the literature (Barclay & Barclay, 1994; Birmingham

et al., 2008; Bowles-Terry, Davis, & Holliday, 2010; Fister, 1992; Hlavaty

& Townsend, 2010; Jacobs & Jacobs, 2009; Mazziotti & Grettano, 2011; Mounce, 2009; Palsson & McDade, 2014; Shields, 2014; Sult

& Mills, 2006; White-Farnham &

Caffrey Gardner, 2014). This review focuses on a few additional works

that most closely relate to our research.

About a

little over a decade ago, Rolf Norgaard (2003) contended that incorporating

concepts from rhetoric and composition into information literacy “would help yield a more situated, process-oriented literacy relevant to

a broad range of rhetorical and intellectual activities” (p. 125). He insisted

that this collaboration would help to transform information literacy practices

from skills-based into a more dynamic practice of intellectual and contextual

inquiry (2003, p.125; 2004, p.221). In exchange, Norgaard believed information literacy

would help to legitimize the study of rhetoric and composition, usually viewed

as part of the Ivory Tower, by investing it in real-world actions (2004, p.

225). Norgaard argued that blending information literary and rhetoric and

composition would help strengthen instruction and contribute to the development

of a “situated” or “rhetoricized” information literacy (2004, p. 221). For Norgaard, these adaptations would help both fields move beyond

surface features and rote search tasks (e.g., grammar and citation) into new

territories of mutual, disciplinary growth.

In this “provocation” for an integrated approach to

information literacy, Norgaard (2004) touches on mutual benefits for each

discipline (p. 225) without entertaining, in depth, potential shortcomings. One

possible complication from this collaborative approach comes out of Norgaard’s

discussion of the language of information literacy. He explained that

instructors of composition and librarians both seek to make research

accessible, relevant, and transparent for students. Considering that jargon

occludes this entry and command of information literacy, he asserted that

framing literacy practices in ordinary language would help to establish common

ground for the complex work that instructors of composition and librarians do

together (2003, p. 126). However, using the language of everyday speech to draw

the fields together and enrich each other, we contend, is far more complex than

sharing theories and pedagogies in mutually respectful teaching and research

environments. Librarians and composition instructors may speak the same

language, but in a manner of speaking, they do not. For students, overlapping

vocabularies produce confusing and sometimes competing conceptions of how to

access and evaluate information.

Research into student evaluative skills primarily

comes from studies of composition and linguistics, in particular the work of

Siew Mei Wu. Assessing the language of evaluation in argumentative essays by student

writers, Wu and Allison (2005) found student writers who supported their thesis

statements with clear, evaluative expression performed better academically than

those who relied primarily on exposition. As students who performed poorly

tended to discuss a topic rather than develop an argument, Wu and Allison found

that “the high-rated essay writers tend to maintain a more dialogically

expansive stance to soften the assertiveness level of the claims” (p. 124). In

part, this “dialogical expanse” develops through fluid integration of sources

that supports clear assertions from the student writer. Examining another

sample of student argumentative writing, Wu (2008) explained that student

writers often lack the disciplinary discourse and jargon to assess and form

their own arguments in writing, but assignments often require them to read the

discourse, understand it, and participate in that academic conversation (p.

59). Students not only have to comprehend the discourse of the documents that

they assess but also understand the language of evaluation used in the

classroom. In general, the implications of Wu’s research (2008) suggest that

students who “situated” their arguments outperformed those who provided vague

details and explanations, namely those who used the language of evaluation

discretely (p. 71). The language of evaluative expression reflects criteria

(e.g., bias, citation, credibility) from both rhetoric and composition and

information literacy. These studies indicate that academic readers assess the

quality of an argument through evaluative language, underscoring the importance

of consistent vocabulary and conceptual frameworks in this process.

As Wu (2008) points out the complex web of discourses

that students try to untangle in order to analyze and evaluate information,

Holliday and Rogers (2013) – in a librarian and writing instructor’s

collaboration – report on the language of information literacy used in the

classroom (i.e., by them and by students) and how that affects students’

engagement with information. They suggest the language of evaluation used by

the two groups alike affects student ability to achieve meaningful and coherent

source evaluation. They assert that the “[i]nstructional discourse” at play

between the librarian and the writing instructor contribute to student

researchers and student writers producing artificial evaluations (p. 259). The

authors propose a shift in both language and “instructional attention” in the

classroom from “finding sources” to a focus on “learning about” sources

(p.268). Our study also examines discourse, but we focus on how two languages

come together – that of information literacy and rhetoric and composition – and

how this union affects how students

evaluate sources in their written work.

One of the goals of information literacy and

composition is to teach students methods of source evaluation, applicable to

many assignments and situations in order to assess the quality of a text and

its argument. These goals seem mutually beneficial and congruent, but we

contend that our language gets in

the way of student uptake and application. To borrow a metaphor from Holliday

and Rogers (2013), these heuristics (e.g., “checklist method”) for source

evaluation are tools that we intend for students to learn and apply in their

research and writing (p. 259). However, we claim that combining information

literacy and rhetoric and composition is like dumping two boxes of tools onto

our students; instead of a smooth and soluble integration, merging discourses

produces a pile of symbolic tools, some similar, some different, some

redundant, and some incomprehensible, that all parties involve need to sort

through.

Aims

We

conducted a semester-long study of one ENGL1120 class, in order to assess how

well students transferred the skills and concepts learned in course-integrated

library instruction sessions to their assignments. From the assessments, we

hoped to identify outcomes for which the librarian could train the instructor

to further discuss with students after the sessions. The unpredictable nature

of assessment led us down a different path, however.

Examination

of topic proposals written after a class on source evaluation revealed

students’ reliance on rhetoric and composition vocabulary to evaluate

information; this occurred, despite explicit instructions to consider what they

had learned from the librarian. The few “information literacy” words used were

closely woven within rhetoric and composition terminology, although most often

ineffectively. We realized that during our planning session for the class, we

had omitted a thorough discussion of each other’s source evaluation discourse.

We contend that this resulted in muddled and superficial evaluations by

students. The discussion below examines how students appropriated the diction

and vocabulary of information literacy and rhetoric and composition following a

session on source evaluation. We share the consequences of a glossed-over

understanding of each other’s language – a somewhat inconspicuous topic that

needs more attention in the literature.

Methods

The

ENGL1120 class that is the focus of this study consisted of 27 students: 20

freshmen, 6 sophomores, and 1 junior with majors in the liberal arts, science

and math, engineering, business, education, and nursing. The first major essay

of this course was a rhetorical analysis of one text, and did not require a

library session. The second essay asked students to locate two texts that were

of comparable genre and rigor on a topic related to cultural

diversity. The instructor hoped that setting limits on the types of sources

that students could compare would help eliminate weak and unbalanced

comparisons that he had graded in previous classes (for instance, comparing

arguments in a peer-reviewed article to the opinions of a blogger). Students

would analyze the sources’ rhetoric guided by instructions provided in the

assignment prompt and explain which author made the better argument and why.

Before students began this essay, the instructor assigned a topic proposal assignment

in the form of a short writing (roughly 250-300 words) to determine whether

students understood the expectations of the larger assignment. The topic

proposal required students to 1) provide a brief summary of each of the

authors’ claims; 2) justify why the articles were of comparable rigor and genre

(students were to consider the information from the library session); 3) defend

the better argument and include the criteria they used to determine this; and,

4) include a plan to support their (the students’) argument and ideas. The

instructor kept the word count low to ensure succinct and well-thought out

evaluations.

During our

pre-class meeting, we outlined a team-taught library session on source

evaluation to coincide with this assignment. In an effort to deemphasize the

evaluation “checklist” and the superficial assessment of information that it

encourages, the librarian suggested a lesson plan centered on the “information

lifecycle.” We also acknowledged and incorporated two terms on the assignment that

the librarian normally did not use; genre,

defined by the instructor as “a category of writing or

art that share similarities in form and style” and rigor, “the thoroughness

and accuracy of a source.” Focus on genre would transform a dichotomous

discussion of the differences in the format of “popular” and “scholarly”

sources to a closer examination of both the way a source looks and the way it is written. Rigor would discourage the assessment of

peer-reviewed articles as being the “best” type of source, but instead

characterize the review process as a factor to consider – and one that should

strengthen – as we moved around the information lifecycle. Throughout the

semester, the instructor framed the concept of rhetorical analysis using the

three Aristotelian, persuasive appeals: logos (e.g., logic, reasoning,

evidence), pathos (e.g., emotionally charged language, anecdotes, narration),

and ethos (e.g., credibility, diction, tone). The pre-class planning session

did not include a discussion of this particular discourse and its relation to

source evaluation. We phrased our learning outcome as follows: “students will

learn that information is disseminated in different formats and that the

accuracy and thoroughness (rigor) of information is often related to the length

of time it takes to produce the information and the format in which it is

reported” (Carter & Aldridge, 2015).

We began

the library session with a review of the concept of genre, which the instructor had introduced in a previous class. He

explained that sources within the same genres share comparable patterns of

arguments, and provided characteristics to consider when identifying a genre:

length, tone, sentence complexity, level of formality and informality, use of

visuals, kinds of evidence, depth of research, and presence or absence of

documentation (Ramage, Bean, & Johnson, 2010). The discussion included

examples of types of genres, such as op-ed pieces and scholarly articles, and the

librarian asked students from which genres they might find sources for their

assignment.

The

librarian next introduced a current event in cultural diversity that would

serve as a class topic. She placed students in groups of two, and then

distributed to each group a piece of paper with a pre-selected source written

on it. The sources represented a variety of genres: broadcast news, online and

print newspapers, magazines, trade magazines, scholarly journals, and books.

Keeping the example topic in mind, students answered worksheet questions about

their source that addressed the information creation process. Prior to class,

the librarian had set up five stations around the classroom that represented a

point in the information lifecycle. She had labeled the stations “one day,”

“one week,” “one month,” “one year,” and “longer than one year.” After they

completed the worksheet, she asked each group to tape their source at the

station along the information lifecycle that most closely matched its speed of

publication. She then led a discussion about the rigor of each as they moved

around the room, and essentially around the information lifecycle. The

discussion incorporated familiar terms such as authority, accuracy, and purpose, but not in conjunction with a

checklist. For a revised version of this lesson plan, see Carter & Aldridge

(2015). The class concluded with an introduction to the Academic Search Premier

database and time for the students to search. After class, the instructor

shared the completed topic proposals with the librarian, and they met several

times to discuss the results. Approval from the university’s Institutional

Review Board was required to conduct the study, and age of consent in Alabama

is 19. This library session occurred early in the semester, before

approximately half of the students turned 19. Therefore, out of the 27

students, we are only able to report on the artifacts of 13 students.

Apart from

one another, we each assessed the topic proposal assignments that students

completed after the library session with the use of two simple rubrics. The

first rubric measured student success at finding articles of similar genre and

rigor. If we graded a paper as “sufficient” or “accomplished” at this task, we

each applied the second rubric to determine how well they justified their

choices. To earn an “accomplished” rating on this second task, a student

“succeeded in convincingly justifying their selections,” while a “sufficient”

rating indicated that the student tried to justify their selections, but fell

short. We reserved “insufficient” ratings for those students who put forth

little effort. Then we came together to discuss each other’s results. We found

that we had each applied the rubric similarly, informally norming the rubric.

In an effort to conduct an organized review of word choices, we identified

categories of evaluative language that the students used in their topic

proposals. The categories listed here were developed through our discussion of

the patterns that each of us identified when we read throught the proposals

separate from one another: logic (logos, evidence, facts, organization,

reasoning); emotion (pathos, personal stories, anecdotes, charged language);

credibility (ethos, ethics, credentials, character, authority); surface features

(mention of length of article, credentials mentioned without analysis, bias,

citations/references); genre (identified a specific genre). We then read

through the papers one last time separately, color-coding for each of the

categories. This enhanced our later discussions by providing a visualization of

the vocabulary patterns.

Results and Discussion

While most

students could locate the “right” types of sources (of similar rigor and

genre), the majority of their attempts to evaluate the sources involved

sweeping statements using the broadest terminology possible. This strategy did not result in

what we considered accomplished evaluations, and we identified three possible reasons

for this poor performance: 1) flawed assignment design – students were asked to

do too much with too few words, therefore could not be as precise as we would

have liked; 2) an ineffective information literacy session; and/or 3) a lack of

clear understanding of evaluative language. While all three represent crucial

pieces of the puzzle, language-use rose to the top for us as the most

stimulating finding of this assessment. We thought this focus would touch on

the other two potential factors as well.

We moved forward

by labeling each evaluative word choice as either an “information literacy” or

“rhetoric and composition” term. We based these labels on the language each of

us most commonly used in our respective classes. Table 1 illustrates students’

choice of words divided by the authors into these two categories.

The

majority these evaluative word choices fell into three categories: logic,

emotion, and credibility. Our discussion below is based on this framework.

Table 1

Word

Choices Related To Information Literacy Or Rhetoric And Composition

|

Information Literacy

|

Rhetoric and Composition

|

|

Credibility

|

Logic

|

|

Authority

|

Evidence

|

|

Format-related

features (e.g., length, credentials, citations)

|

Facts

|

|

|

Organization

|

|

|

Reasoning

|

|

|

Emotion

|

|

|

Pathos

|

|

|

The use of

personal stories

|

|

|

The use

of “charged” language

|

|

|

Character

|

|

|

Genre

|

Logic

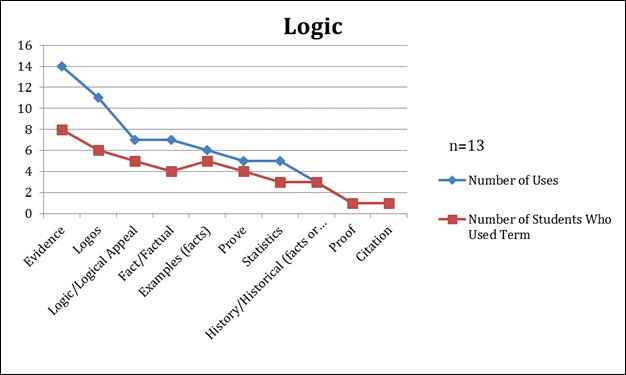

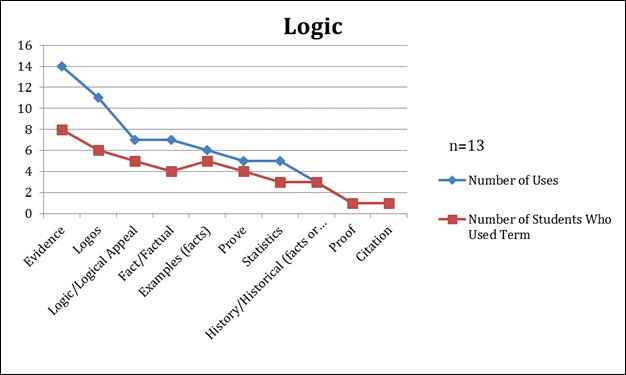

Figure 1 shows the words students chose

when referring to the logic of an author. The librarian discussed reference lists and citing sources in the information literacy session, and the

importance of each in determining authority

and accuracy. However, students

mostly chose less-specific concepts found in their composition reader.

Figure 1

Student

word choices related to logic.

For

example, rather than explaining that an author had “cited sources,” students

preferred the term “evidence.” This may seem like a trivial difference, until

the applications of the word and its effect on student performance is

considered. Student 1 in our

sample used the word evidence three separate times. The student describes,

“[The author] begins by explaning he first believed that gun control was a

positive move forward, but later changed his

thesis after considering evidence. Although the student impressively

applies the language of rhetorical analysis (e.g, “his thesis”), he or she

makes no clear point about what type of evidence swayed the author to change

positions. Evidence seems like whatever material the author uses to support his

or her point. Later, the student gets somewhat more specific, adding adjectival

modifiers to differentiate types of evidence: “[Both articles] support their

evidence through historical evidence.”

This seems like a firm step toward specific evaluative analysis. Narrowing

evidence into manageable categories begins to demonstrate the student’s

awareness of different types of evidence and their potential uses. However, the

student made up this category of evidence on the spot, since it was not

introduced in discussions during the library sessions or during writing class.

What consitutes historical evidence and why it matters in evaluating the author

and the source’s effectiveness are simply mentioned and then abandoned. Next,

the student continues to bring the discussion into more focus: “[The author]

uses some factual based evidence, but

lacking a proper amount of citation

and logical appeal.” Factual-based

evidence seems like a straightforward categorization – it’s evidence based on

facts. Questions remain, however, and many go unanswered or unaddressed about

the nature and origin of those facts. What, moreover, is the “proper amount of

citation” to appeal logically and appropriately to the audience? Why is that

the case? Why are some facts more persuasive, reliable, and fitting for one

audience over others? How and why? It’s repetitive questioning, no doubt, but

important for evaluating a source beyond its surface functions, parts, and

pieces. Those deep level analytical questions are left in favor of shallow

responses. This student’s identifications of evidence capture a dominent trend

that runs through the entire sample –students disregarded the suasive function

of the types of evidence used to describe the article. If it has evidence, it

is a good source. If it has more evidence than the other source, it is likely

better. There is little mention of the quality of evidence, or sources,

consulted. Immersing

students in this vague terminology provided

them with the flexibility to make words mean what they wanted them to mean – it

required less thoughtful evaluation and less critical thinking.

Emotion

As we identified

parallels within our two lexicons, we ran into a discrepancy when considering pathos and emotion. The librarian considered emotion to be connected to bias, while the composition instructor

argued that bias, although it might

be included under pathos, primarily falls within ethos and speaks to the credibility

of an author. This in itself serves as a valuable illustration of lexical

mismatch. For the purposes of this discussion, we favor the composition

instructor’s view. As seen in Figure 2, students pulled from a limited

vocabulary when discussing pathos.

Although students

generally made empty evaluations of pathos (similar to those discussed in the

logos section), they found a lack of emotional appeal as a real problem. Beyond

unsound logic, unreasonable beliefs, or tenuous support, students often

condemned an author who failed to move readers emotionally. One student claimed

that strong pathos was the crucial evaluative element between his or her

authors: “The main point I will make in my essay, though, is the lack of pathos

in [the author’s] article. [The other author] fills his article with emotional

appeal, which makes it very strong.” Although the students made clear claims

about the effectiveness of pathos, what their proposals leave out are specific

details. How do these authors affect readers? Why is that

specific method weak or strong or persuasive? These questions we both want to

know.

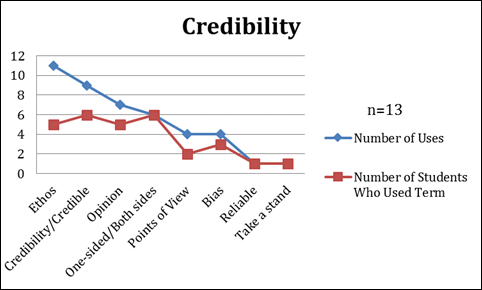

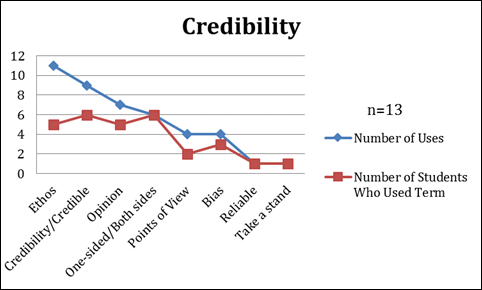

Figure 2

Student

word choices related to emotion.

Figure 3

Student

word choices related to credibility.

However,

one student stood out from this sample. This student often leads with

generalities, most of the writers from our sample do, but he or she steps toward

specific evaluation through analysis. Analyzing and evaluating two sources

about the legalization of marijuana, the student starts with a vague statement,

introducing the rhetorical category: “[‘Article Title’] will be addressed by

showing [the author’s] lack of logical evidence and no emotional appeal to his

audience.” The student’s claim to “no emotional appeal” is sweeping and

inaccurate, since no document completely lacks the ability to affect an

audience, even if it produces boredom or contempt. He restates this position

further: “[The Author] also does nothing to connect with the people that don’t

use the drug while he is arguing against the legalization of marijuana thus

showing his lack of emotional appeal.” Although the student made weak claims about

pathos of the article considered rhetorically weaker, he or she treated the

source considered rhetorically effective more precisely. “[The other author’s]

article is more effective than ineffective because of his use of strong

emotional appeal and his use of situations that his intended audience can

easily relate to.” The student doesn’t connect that “his use of situations” are

a facet of “strong emotional appeal,” which is an enormous category. He

reiterates later, “[the author’s] use of situations that make his argument easy

to relate to.” By situations, the student means to describe narratives,

anecdotes, or descriptions that the author uses to concretize the policies for

which he argues. In addition to identifying a specific emotional strategy used

by the author, this student reaches a solid conclusion regarding the emotions

that the author intends to elicit from the audience: “He also evokes sympathy

and happiness at different times as he shows the marijuana dispensaries being

shut down and the excitement of citizens in states where the drug was

legalized.” The mention of “sympathy and happiness” seems like small steps and

still somewhat vague, yet, unlike most of our sample, this student actually

proposed specific emotions rather than simply mentioning “appeals to emotion”

or “uses pathos.” This is the type of evaluation and analysis that we encourage

in student evaluation because it, at the very least, displays a measure of

critical, evaluative thinking.

The many

emphatic criticisms levied against an author’s pathos suggest that students may

need instruction on how to distance their personal point of view during source

evaluation yet register their reactions to emotive language carefully. That

they produce circular evaluations about pathos might seem removed from the

librarian’s goals, but the student’s fixation on emotional appeal and swift

criticism of the lack thereof might suggest that they are not thinking

critically about finding and evaluating the best sources. In fact, their

examinations of and references to pathos suggest that affective language may

influence student source decisions in a detrimental way.

Credibility

Arguing for an

author’s ethos, authority, credibility,

under whatever name, eluded many students from our sample. A factor contributing

to students’ poor performance could be our two similar but competing

definitions of authority. The

librarian took a traditional (albeit changing) approach to teaching authority

by focusing on an author’s credentials. For composition, ethos takes this oversimplified view into consideration, but also

requires evaluating how an author exhibits authority through proper diction and

ethical claims. Furthermore, a credible author

should present counterarguments fairly, and if he or she does not, then their

manipulation of information or bias

might compromise their ethos, their credibility. The information literacy

approach promoted a surface-level evaluation, while the rhetorical analysis of authority required a thorough reading

and comprehension of the source. Students applied the librarian’s definition of

authority and tried to make it fit the rhetorical analysis ethos-framework.

Rather than using the term authority,

however, they chose to use credible –

a word not formally defined in class, but rather tossed around loosely by the

librarian without considering the implications for student understanding.

For example, one

student acknowledged, “Both of the authors appeal to ethos almost equally due to their credibility and background.” Another student remarked, “The author

in article one has many ethos that

help to [sic] his argument which make him credible.”

Essentially, the students decided that the author is credible because he or she

is credible. Although they show awareness of credibility and its importance for

evaluating sources, their circular arguments demonstrate missing analytical

tools for identifying specific appeals to credibility.

Few

students constructed nuanced analyses and evaluation of credibility. These

examples, however, indicate awareness of the implicit nature of ethos assembled

by the parts of writing. One student claims, “Throughout the article she [the

author] is very sincere and seems to really care that texting while

driving should be banned.” This student reaches a conclusion based on

synthesizing the parts of the argument. This may seem vague, but his or her

point speaks to the tone and voice of the author in the article, rather than

the external factors, like credentials or publisher, on which most students

remarked. The same student states, “[The other author] uses ways of relating to

both sides,” an instrumental gesture for conveying fairness and comprehension

in an argument. Had the student identified what specific components of writing

and argument made this first author appear “very sincere” or seeming “to really

care” or what “ways of relating to both sides” used by the second author, he or

she would advance toward strong evaluation of ethos. That he or she sees beyond

the surface, beyond the literal demonstrates analysis and evaluation that we

encourage and endeavor to replicate in student scholars. Another student,

writing about atheism and theism, drew out that one of his or her author’s was

more persuasive than the other because of her “understanding and placating

tone, and her experience with both sides of a theistic existence.” This student

recognizes the author’s intention of forging common ground over a contentious

topic with a potentially hostile audience comes through how she writes and not

simply what. His or her evaluation of the author’s ethos, though minor, stands

out from our sample because the student compresses several dimensions of

ethical credibility into one single sentence. However, these evaluative

statements were the exception and not the rule.

In addition,

limited class time meant that some crucial points were glossed over.

Unfortunately, students walked away with the impression that bias was bad, and

could most often be identified as one-sided.

They ignored discussions of bias led

by the instructor throughout the semester in which he presented one-sided as arguments slanted toward an

audience in favor of the topic (e.g., arguing for a better football stadium to

football fans) as well as an argument without consideration or acknowledgement

of counterarguments. For instance, one student, comparing argumentative

articles on the issue of abortion, accuses an author of a pro-life argument to

be “rhetorically ineffective” because of “presenting a one-sided argument.” This conclusion may be the building block of a

strong, detailed evaluation. However, in comparing the two articles, the

student concludes, “They have similar genres in which the author has a one-sided point of view and uses

specific detail to argue pro-life or pro-choice.” In the same paper, the

student changes use of the term “one-sided,” maintaining it as a point of

comparison between the two sources. For this student writer, the “one-sided”

approach clarifies the author’s argument and intention, forgoing engagement

with counterarguments or introducing alternative perspectives in a fair and

comprehensive manner. The phrase contributed to dichotomous evaluation of

information.

Limitations of Study

In consideration

of the problems with our instruction, one issue stands above the rest. The

composition instructor’s assignment asked students to say too much in very few

words. The instructor had intended for students to demonstrate basic

understanding of the major essay’s purpose and show that they had, in fact,

started the writing and researching process. However, compressing a summary, a

justification, and a developing argument into 250 to 300 words, simply could

not be done well. Rather than increase word count, it may be more productive to

cut the objectives and focus the assignment on justifying their choices. This

might yield more developed and thoughtful conclusions. Having said this, we

believe if provided with a larger sample, we would most likely see similar trends

as seen in Figures 2, 3, and 4 – students’ inclination to use broad, somewhat

meaningless words. We cannot prove this with our data, however, but hope others

will take up this research and move it forward.

That the

language of information literacy was mostly missing from their analyses raises

an important question. How effective was the instruction session when most of

the information literacy terms were never used in the students’ writing? Is it

realistic to expect students to remember a multitude of terms, comprehend the

meanings of these terms, and apply them appropriately after a 50-minute

information literacy session? Instruction prior

to and during the information literacy session may have steered students in the

wrong direction. Before the session, the composition instructor presented

information on genre to students using genres that he hypothesized they were

familiar with (e.g., action films, teen dystopian novels, etc.) as a way to

help them approach analyzing and evaluating more conventional college-level

sources (e.g., op-ed pieces, peer-reviewed articles, etc.). Using examples from

popular culture only to build common

ground for understanding the concept of genre, however, may have stunted

students’ ability to see the transferability of these skills to the evaluation

of academic sources. Moreover, the librarian fell short in her attempt to fully

move away from the “checklist approach” by encouraging students to rely on

author’s credentials for authority, rather than considering information need,

or the instructor’s definition of authority.

Implications and Conclusion

Reflecting

back on our project, students spent more time with the instructor and had more

incentive to use his language given that he graded their work. Our research

showed that the words used by the instructor – ethos, evidence, so forth – took

on different forms for the librarian, such as sources, references, etc. It may seem that the instructor and librarian were saying the same

things, but just using different words. Based on the students’ writing and the

instructor and librarian’s consultations afterwards, however, these seemingly

similar words had different meanings. It seems like we’re arguing semantics here, which is

commonly seen as nitpicky and frustrating. But, in this case, semantics matter.

Are our languages similar enough that we can have a common vocabulary or do we

need a better understanding of our languages so we’re not working at

cross-purposes? Are we enabling students to take the easy way out because of

the inconsistencies in the languages that we use?

We contend

that both sides’ concept of sources could serve as a starting point for a more

blended discourse. In the information literacy session discussed above, the

word genre replaced source and format in the traditional framework of popular versus scholarly

sources. Through our post-class discussions, we learned that we both meant

basically the same thing, but just expressed it differently. Burkholder (2010)

speaks to this by arguing for the use of genre theory to redefine sources by “bridging the gap between

what a form really is and what it is actually designed to do” (p. 2). Bizup

(2008) argues in favor of a vocabulary to describe how writers use sources, rather

than for types of sources (p. 75). This could be a perfect opportunity to

combine ideas from rhetoric and composition and information literacy to create

a mutually-endorsed descriptor. However, this requires a higher-level of

understanding of each other’s discourse. Siloing our thoughts and concepts into

distinct teaching responsibilities (i.e., you teach this, I teach that) will no

longer suffice. Composition represents only the beginning of the journey, as

discourse becomes more complex as students’ progress through their majors.

Frank conversations with faculty about the purpose of information literacy

instruction and their expectations of student performance must also include a

discussion of disciplinary discourse. Clear language serves as the crux of

comprehension.

At the end of

our analysis, the paths forward split in many directions. One way is toward

further standardization of conceptual vocabulary for source evaluation. If

instructors of composition and librarians shared identical language and

methods, confusions and redundancies in our respective approaches and wordings

would likely decrease. However, another way forward is to keep going in the

same direction, stay the course, in other words. Composition instructors and

librarians join together and meld their methods organically. Though this

process may be messy, the results may better mirror the challenge for our

students who have to navigate through the unfamiliar terrain of source

evaluation in the information age. Standardization may strip away our students’

creative edge needed to cut away ambiguity and fabrication of authority during

a time when information flows as freely as air and can likely be as

insubstantial. By bringing various languages of source evaluation together, our

process becomes one of many methods, not the method but a method,

available to students who need to learn to adapt to varying audiences and

demands in order to evaluate work in meaningful ways, rather than blankly

repeating vocabulary.

The endless

flexibility in and between different academic disciplines challenges first-year

students. When the language of rhetoric and composition and information

literacy collide in the classroom, expect a crash in the students’ minds. They

have to learn to adapt to multiple discourses, sets of words and principles of

knowing, in a single classroom for each assignment. Assuming a

“fake-it-until-you-make-it” voice in their academic writing helps them gesture

toward the clear and specific evaluations that we strive to teach our students.

Despite the

limitations of our study, we feel as though we have stumbled upon an issue

relevant to all librarians who communicate with students, composition

instructors, and disciplinary faculty. Understanding the role discourse plays

in student learning should be embedded in our advocacy for information

literacy.

References

Adedibu, L.O. & Ajala, I.O. (2011). Recognition of library terms and

concepts by undergraduate students. Library

Philosophy and Practice (e-journal). Paper 449. Retrieved from http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/libphilprac/449/

Association of College & Research Libraries. (2015). Framework for information literacy for

higher education. Chicago: American Libraries Association. Retrieved from http://www.ala.org/acrl/standards/ilframework

Ayre, C., Smith, I.A., & Cleeve, M. (2006). Electronic library

glossaries: Jargonbusting essentials or wasted resource? The Electronic Librarian, 24(2),

126-134. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/02640470610660323

Barclay, D.A. & Barclay, D.R. (1994). The role of freshmen writing in

academic bibliographic instruction. The

Journal of Academic Librarianship, 20(4),

213-217. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0099-1333(94)90101-5

Benjas-Small,

C., Archer, A., Tucker, K., Vassady, L., & Resor Whicker, J. (2013). Teaching

web evaluation: A cognitive development approach. Communications in Information Literacy, 7(1), 39-49. Retrieved from http://www.comminfolit.org/index.php?journal=cil&page=article&op=view&path[]=v7i1p39

Birmingham, E.J., Chinwongs, L., Flaspohler, M.R., Hearn, C., Kvanvig,

D., Portmann, R. (2008). First-year writing teachers, perceptions of students’

information literacy competencies, and a call for a collaborative approach. Communications in Information Literacy, 2(1), 6-24. Retrieved from http://www.comminfolit.org/index.php?journal=cil&page=article&op=viewArticle&path[]=Spring2008AR1&path[]=67

Bizup, J. (2008). BEAM: A rhetorical vocabulary for teaching

research-based writing. Rhetoric Review,

27(1), 72-86. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/07350190701738858

Bowles-Terry, M., Davis, E., & Holliday, W. (2010). “Writing

information literacy revisited”: Application of theory to practice in the

classroom. Reference & User Services

Quarterly, 49(3), 225-230.

Burkholder, J.M.(2010). Redefining sources as social acts: Genre theory

in information literacy instruction. Library

Philosophy and Practice, Paper 413. Retrieved from http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/libphilprac/413

Carter, T.M. & Aldridge, T. (2015). Information life cycle. In P.

Bravender, H. McClure, & G.Schaub (Eds.), Teaching information literacy threshold concepts: Lesson plans for

Librarians, 94-98. Chicago: Association of College and Research

Libraries.

Chaudhry, A. S. &

Choo, M. (2001). Understanding of library jargon in the information seeking

process. Journal of Information Science, 27(5), 343-349.

Dewey, B.I. (1999). In

search of services: Analyzing the findability of links on CIC University

Libraries’ web pages. Information

Technology and Libraries, 18(4), 210-213. Retrieved

from http://www.ala.org/acrl/sites/ala.org.acrl/files/content/conferences/pdf/dewey99.pdf

Doran, K. (1998).

Lamenting librarians’ linguistic lapses. American

Libraries, 29(7), 43.

Fister, B. (1992).

Common ground: The composition/bibliographic instruction connection. In T.

Kirk (Ed.), Academic Libraries: Achieving

Excellence in Higher Education (pp. 154-158). Chicago: Association of

College and Research Libraries.

Foster, E.H. (2010). An examination of the effectiveness of an online

library jargon glossary. (Unpublished master’s thesis). University of North

Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC. Retrieved from http://dc.lib.unc.edu/cdm/ref/collection/s_papers/id/1214

Holliday, W. & Rogers, J. (2013). Talking about information literacy:

The mediating role of discourse in a college writing classroom. Libraries and the Academy, 13(3), 257-271. http://dx.doi.org/

10.1353/pla.2013.0025

Houdyshell, M.L. (1998). Bring out the best in your BI or converting

confusion into confidence. College &

Undergraduate Libraries, 5(1),

95-101. http://dx.doi.org/

10.1300/J106v05n01_11

Hutcherson, N. B.

(2004). Library jargon: Student recognition of terms and concepts commonly used

by librarians in the classroom 1. College and Research Libraries, 65(4),

349-354. http://dx.doi.org/ 10.5860/crl.65.4.349

Hlavaty, G. &

Townsend, M. (2010). The library’s new relevance: Fostering the first-year

student’s acquisition, evaluation, and integration of print and electronic

materials. Teaching English in the

Two-Year College, 38(2), 149-160.

Retrieved from http://www.ncte.org/library/NCTEFiles/Resources/Journals/TETYC/0382-dec2010/TETYC0382Librarys.pdf

Imler, B. &

Eichelberger, M. (2014). Commercial database design vs. library terminology

comprehension: Why do students print abstracts instead of full-text articles? College

& Research Libraries, 75(3), 284-297. http://dx.doi.org/

10.5860/crl12-426

Jacobs, H. L. M., &

Jacobs, D. (2009). Transforming the one-shot library session into pedagogical

collaboration: Information literacy and the English composition class. Reference

& User Services Quarterly, 49(1), 72-82. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/20865180

Mazziotti, D. &

Grettano, T. (2011). “Hanging together”: Collaboration between information

literacy and writing programs based on the ACRL standards and WPA outcomes. In

D.M. Mueller (Ed.), Declaration of

Interdependence: The Proceedings of the ACRL 2011 Conference, March 30-April 2,

2011, Philadelphia, PA (pp. 180-190). Chicago, IL: Association of College

and Research Libraries. Retrieved from http://www.ala.org/acrl/sites/ala.org.acrl/files/content/conferences/confsandpreconfs/national/2011/papers/hanging_together.pdf

Meola, M. (2004).

Chucking the checklist: A contextual approach to teaching undergraduates

web-site evaluation. Libraries and the

Academy, 4(3), 331-344. http://dx.doi.org/10.1353/pla.2004.0055

Mounce, M. (2009).

Academic librarian and English composition instructor collaboration: A

selective annotated bibliography, 1998-2007. Reference Services Review 37(1),

44-53. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/00907320910934986

Naismith, R., &

Stein, J. (1989). Library jargon: Student comprehension of technical language

used by librarians. College and Research Libraries, 50(5), 543-552. http://dx.doi.org/ 10.5860/crl_50_05_543

Norgaard, R. (2003).

Writing information literacy: Contributions to a concept. Reference & User Services Quarterly, 43(2), 124-130. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/20864155

Norgaard, R. (2004).

Writing information literacy in the classroom: Pedagogical enactments and

implications. Reference & User

Services Quarterly, 43(3),

220-226. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/20864203

Palsson, F., &

McDade, C. L. (2014). Factors affecting the successful implementation of a

common assignment for first-year composition information literacy. College

& Undergraduate Libraries, 21(2), 193-209. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10691316.2013.829375

Pinto, M., Cordon, J. A., & Gomez Diaz, R. (2010). Thirty years of information literacy

(1977-2007): A terminological, conceptual and statistical analysis. Journal of Librarianship and Information Science,

42(1), 3-19. http://dx.doi.org/

10.1177/0961000609345091

Ramage, J.D., Bean, J.C., & Johnson, J. (2010). Writing arguments: A rhetoric with readings (Custom ed. for Auburn

University). Boston: Pearson.

Shields,

K. (2014). Research partners, teaching partners: A collaboration between FYC

faculty and librarians to study students’ research and writing habits. Internet

Reference Services Quarterly, 19(3-4), 207-218. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10875301.2014.983286

Sonsteby, A. & DeJonghe, J. (2013). Usability testing, user-centered

design, and LibGuides subject guides: A case study. Journal of Web Librarianship, 7(1),

83-94. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/19322909.2013.747366

Spivey, M. A. (2000).

The vocabulary of library home pages: An influence on diverse and remote

end-users. Information Technology and Libraries, 19(3), 151-156.

Sult, L. & Mills,

V. (2006). A blended method for integrating information literacy instruction

into English composition classes. Reference

Services Review, 34(3), 368-388. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/00907320610685328

Swanson, T.A. &

Green, J. (2011). Why we are not google: Lessons from a library web site

usability study. The Journal of Academic

Librarianship, 37(3), 222-229. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2011.02.014

White-Farnham, J. & Caffrey Gardner, C. (2014).Crowdsourcing the

curriculum: Information literacy instruction in first-year writing. Reference Services Review, 42(2), 277-292. http:dx.doi.org/10.1108/RSR-09-2013-0046

Wu, S.M. (2008). Investigating the effectiveness of arguments in

undergraduate essays from an evaluation perspective. Prospect, 23(3), 59-75. Retrieved from http://www.ameprc.mq.edu.au/docs/prospect_journal/volume_23_no_3/23_3_Art_5.pdf

Wu, S.M. & Allison, D. (2005). Evaluative expressions in analytical

arguments: Aspects of appraisal in assigned English language essays. Journal of Applied Linguistics, 2(1), 105-127. http://dx.doi.org/10.1558/japl.2005.2.1.105

![]() 2016 Carter and Aldridge. This is an Open

Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0 International

(http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

2016 Carter and Aldridge. This is an Open

Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0 International

(http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.