Introduction

Academic libraries are increasingly emphasizing the

entire user experience for their customers and seek to provide not only

outstanding collections but also services and programs that contribute to

student success and faculty research as well as facilities that provide

learning spaces. Much of the user experience conversation focuses on efficient

online accessibility and discovery. Recently, however, Bell called for academic

libraries to “commit to a total, organization-wide effort to design and

implement a systemic UX.” Bell also advocated for “shifting the academic

library experience from usability to totality” (Bell, 2014, p. 370). Many

libraries are hiring librarians with job titles such as “User Experience

Librarian” and engage in a wide variety of assessments to gain knowledge about

what students and faculty seek in library services. Much of this research

employs ethnographic studies originating with the excellent University of

Rochester work where they tracked students’ research patterns using a variety

of methods such as photo surveys and mapping diaries (Foster & Gibbons,

2007; Foster, 2013). In 2011, the Association of Research Libraries (ARL)

published a SPEC Kit, Library User

Experience that outlined numerous types of user assessments employed at ARL

libraries including surveys, facilities studies, focus groups, and usability

studies (Fox & Doshi, 2011).

One aspect of the user experience that remains crucial

is excellent customer service both face-to-face and virtual. Although libraries

seek to make the online and in-house user experience as self-service as

possible, customers still require both directional and in-depth assistance to

find the information and services they need. Furthermore, as libraries seek to

become information hubs and learning centers it is necessary that students have

a good customer experience so that they view the library as a comfortable and

welcoming place. Fair or not, we are aware that users compare the customer

service we provide in the library to that offered in retail shopping areas such

as bricks and mortar book stores and by other retail services such as the Apple

Store. In a 2011 study, Bell surveyed college students to compare their

experiences in libraries to retail using an instrument from the Study of Great Retail Shopping Experiences

in North America. Fortunately, libraries compared well! One factor in the

survey includes “engagement” characterized by politeness, caring and listening.

Bell recommended that academic librarians focus their efforts on less tangible

“soft skills” such as eye contact, patience, and making customers feel

important (Bell, 2011).

With these customer service issues in mind, The

University Libraries at The University of North Carolina at Greensboro sought

to assess the service experiences of students for both in-house and virtual

services. The University of North Carolina at Greensboro, part of the 17-campus

University of North Carolina system, is a publicly-supported university with a

High Research Activity Carnegie classification. In 2015 the total enrollment

was 19,398 with a faculty of approximately 1,000. The University Libraries

include the Walter Clinton Jackson Main Library and the Harold Schiffman Music

Library. At the time of the initial study, Jackson Library had two public

service points; Reference and Access Services (Checkout) on the first floor.

Later, the Special Collections and University Archives (SCUA) department added

a service point on the second floor and was included in the second study. The

Schiffman Music Library has one combined service point. These services desks

are staffed by professional librarians, paraprofessional staff, and student

employees. The two service points (the Reference Desk in Jackson and the front

desk at Schiffman) both employ graduate students from the Libraries and

Information Studies program as interns.

Previous assessments conducted by the University

Libraries indicated positive results for services. In 2008 the Libraries

conducted LibQual+® and the overall perceived mean for “Affect of Service” was

7.5 on the nine-point scale. Every three years the UNC system conducts surveys

of all sophomores and seniors which include questions about library services.

In the 2010 senior survey the Libraries scored 3.5 on a four-point scale for

“staff responsiveness” and 3.6 for “library services overall”. Longitudinally,

we showed improvement in these categories since 1998 when we scored 3.2 on both

these questions. In the 2010 sophomore survey the Libraries received 4.1 out of

5 on “helpfulness of staff.” Because this survey was newly revised that year we

don’t have longitudinal data for it (UNCG University Libraries, 2016).

Although the Libraries performed well on these

assessments they were satisfaction surveys rather than in-depth studies focused

on the user experience. And, while most qualitative comments on the 2008

LibQual+® survey were very positive, some indicated that users had less than

satisfactory interactions at service desks:

“I sometimes

find the student staff to be really annoyed at having to help me, even just

checking out books.”

“I cannot send

my students to the library with confidence that they will be treated with the

same respect.”

Both Jackson and Schiffman offer computers with a wide

variety of software, group and quiet study space and technology checkout as

well as traditional print and AV materials. Chat, email, and texting are

offered in addition to in-house service. Jackson Library has a 24/5 space that

is very popular. Together the Libraries have over 1 million visitors each year.

Like many academic libraries, we are realigning service staff to rely more on

paraprofessionals for reference service so that librarians may focus on

information literacy and specialized liaison services. Often these staff

members are not part of the Research, Outreach and Instruction Department (ROI,

formerly called the Reference & Instructional Services Department) which

can present training challenges. The reliance on student employees with a high

turnover rate can also make it difficult to provide consistent service. After

administering the Association of Research Libraries’ LibQual+® survey in 2008

the Libraries sought to enhance the quality of the customer experience at

service desks and via phone and chat. To begin the process, the Associate Dean

for Public Services charged a task force in 2009 to develop customer service

values to serve as a guide for both external and internal service. These values

were vetted among the public service departments and posted on the Libraries’

web page along with the Libraries’ mission statement, to indicate to both

patrons and staff that we are committed to quality service. (UNCG University

Libraries, 2015a). The task force recommended a training program for customer

service that “should be shaped through ongoing assessment.”

Literature Review

Mystery shopping is a term that is familiar in

industries that are heavily focused on customer service such as financial

services, retail, restaurants, and hospitality. In 2010, the mystery shopping

business was “estimated to be a $1.5 billion industry, up from roughly $600

million in 2004” (Andruss, 2010). Many of the industries that use mystery

shopping use professional services organizations that hire and train the

shoppers. There have also been attempts to utilize the mystery shopping concept

in other non-customer-service areas, such as patient satisfaction with health

care services. And, while much of the literature once focused on mystery

shopping done in person, work is now being conducted to evaluate the quality of

services delivered in virtual environments. According to the 14th annual

Mystery Shopping Study conducted by The E-Tailing Group… “the study confirms

that merchants are refining online tactics to find, inform, personalize and

connect with improved speed and efficiency, while diligently developing social

and mobile initiatives” (Tierney, 2012). In areas that are profit-driven,

mystery shopping has been used to measure up-selling offers (Peters, 2011) and

identify employees with promotional potential (Cocheo, 2011).

An early use of mystery shopping in a library took

place in 1996 in a public library in Modesto, California. Mystery shoppers were

used to assess the library’s customer service, as part of the county’s quality

service initiative (Czopek, 1998). Subsequent use of mystery shopping in

libraries has been to measure the quality of the customer service experience;

there is not, however, a universal definition of quality customer service. In

addition, there is not a universal way to assess quality of customer service.

Is it the amount of time a person has to wait to speak with someone at the

reference desk? Is it providing free coffee to students at exam time? Is it

offering resume writing and computer workshops at public libraries in response

to the needs of the local community (Roy, Bolfing & Brzozowski, 2010)?

Another factor that must be considered is that, in many instances, the library

may be considered a “self-service” organization; patrons can come into the

library or visit the website, and in many instances find what they are looking

for without requesting assistance from library personnel. Even those that do

not find what they are seeking still may not approach a service point (in-house

or virtual) for assistance.

The literature also shows that the use of mystery

shoppers is as varied as the desired outcomes. For some libraries, when

measuring customer service quality, the focus could be on the accuracy of

answers received at the reference desk (e.g. Kocevar-Weidinger, Benjes-Small

& Kinman, 2010; Tesdell, 2000). There are studies that use mystery shopping

to judge the accuracy of answers received during a reference interview as well

as an assessment of the appropriateness and accessibility of physical space and

signage (Tesdell, 2000). Another use of mystery shopping is the assessment and

development of customer service training needs. The assessment for training

needs is not only confined to the front-line public services staff — Reference

and Access Services/Circulation department staffs — but also internal

departments as well, such as the human resources department. In one library,

they worked with the state’s Small Business Development Center to tailor the

mystery shopping process for the needs of their library. Various service points

were “shopped” and they made sure to include a variety of customers so that

they could get a better idea of the needs of diverse populations such as

patrons whose first language was not English, parents with children, etc. Their

shoppers used repeat visits (5 times) in order to relieve employee concerns

about the impact of workload variability on the customer service encounter and

consistency of responses (Backs & Kinder, 2007). At Florida International

University, mystery shopping was used on student employees initially as a way

to assess how the service being provided “felt” to the patrons, to determine if

additional training would be needed and to determine which areas needed

improvement, based on patron feedback. Additional shopping trials were used

after an organizational change resulted in combined service points. The later

mystery shopping assessments focused not only on accuracy of the responses but

also on service provider behaviour. (Hammill & Fojo, 2013)

Support and agreement by stakeholders is always

crucial in implementing a mystery shopper initiative in a library. For public

libraries, authorization by the library board or employee union may be required

prior to implementing such a program. For academic libraries, the permission of

the university’s Institutional Review Board (IRB) will probably be required

(Benjes-Small & Kocevar-Weidinger, 2011). Benjes-Small and

Kocevar-Weidinger also discuss the importance of using written guidelines of

appropriate behaviour to which all staff are exposed as a way to measure

whether or not customer services standards are being met. Both authors used

students as mystery shoppers. At Longwood University, the results of the survey

were used as a part of the employees’ performance review, which resulted in

revised job descriptions and using the mystery shopper assessment to measure

progress (Benjes-Small & Kocevar-Weidinger, 2011).

In some instances, the results of mystery shopper

evaluations have been received as unwelcome surprises to the library staff.

There are also instances in which library staff resist efforts to measure

quality library customer service output in the same way as customer service is

measured in a retail operation (e.g. Deane, 2003; Gavillet, 2011; Hernon,

Nitecki & Altman, 1999). Most of the literature shows that mystery shopping

efforts have been focused only on the delivery of customer service to external

users and not internal customer service providers, such as cataloguing,

acquisitions, or administration.

The majority of efforts to use mystery shopping in

libraries occur in the public library sector. Depending on the environment

(unionized or civil service), there may be barriers to using mystery shopping

as a measurement of job performance or as an assessment of promotional

potential. Academic libraries and public libraries do have many commonalities,

but also have differences in their missions as well as a different patron base.

One of the commonalities of both academic and public libraries is that, unlike

retail establishments, libraries do not have a vested interest in trying to get

a patron to “buy” additional products and services; however, library employees

should have a vested interest in ensuring that the patron is aware of the

products and services that could be of assistance, either at the time of the

visit, or during a future one. Both academic and public libraries should seek

to create an environment where customers (or patrons) are comfortable seeking

assistance within any service point. The Association of College and Research

Libraries (ACRL) 2012 “Top Ten Trends for Academic Libraries” included

“staffing” and “user behaviors and expectations” as important issues (ACRL,

2012). Library users often base their expectations of customer service on that

which is provided in non-library environments. As stated by Connaway, Dickey,

and Radford, “Librarians are finding that they must compete with other, more

convenient, familiar, and easy-to-use information sources. The user once built

workflows around the library systems and services, but now increasingly the

library must build its services around user workflows” (Connaway et al., 2011).

Failure to assess customer service delivery and the quality of that delivery

would mean we are ignoring the needs of our users. Users who feel their needs

are being ignored will turn to other, more welcoming, resources regardless if

they are the best ones for their need.

Method and Procedures

After reviewing the literature, the Libraries

determined that the mystery shopper protocol was the best method to assess our

service interactions and accomplish our goal of determining if our customer

service was indeed meeting the established customer service values. The study

completed at Radford and Longwood Universities in 2010 was an excellent model

and we adapted their protocol for our project (Benjes-Small &

Kocevar-Weidinger, 2011. We conducted the first mystery shopper assessment in

fall 2010 and included desk and phone service for all service points —

Reference and Checkout in Jackson and the service desk in Schiffman — and chat

service for Reference. The research team included the Associate Dean for Public

Services, the Human Resources Librarian, and the Assessment Analyst. Because

secret shopping is a standard in service industries we collaborated with UNCG’s

Hospitality and Tourism Management Department to recruit students as shoppers.

A professor agreed to award extra credit to students who participated. We also

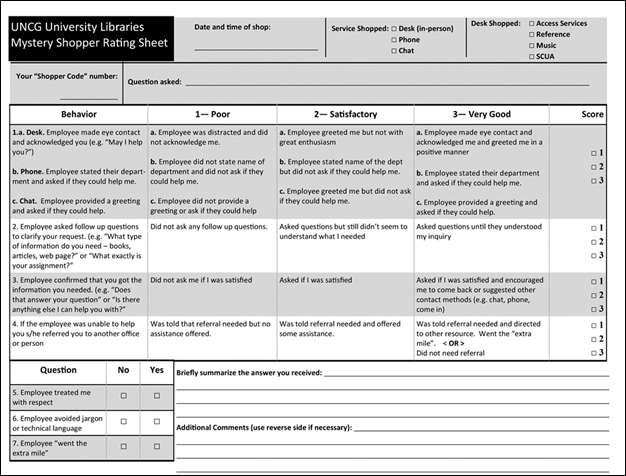

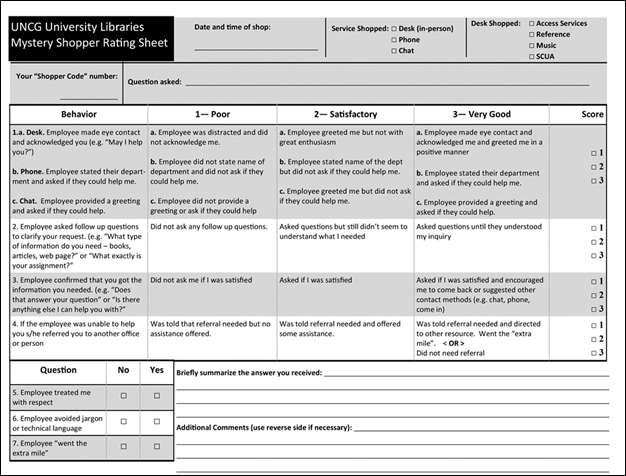

gave them a $10 credit for the campus food service. We developed a rating sheet

(See Appendix 1) for the students to use based on the customer service values

mentioned above. Although we certainly care about accuracy, the emphasis for

this assessment was on the customer service experience.

We included four behaviours: greeting, follow-up, confirmation of satisfaction

and referral, with three levels of rating: 1(Poor), 2(Satisfactory) and 3(Very

Good). Brief descriptions of each behaviour were included on the rating sheet

along with criteria for each level and type of service. For example, for

greeting at a service desk, the following guidance was provided:

- Very

good – Employee made eye contact, acknowledged me and greeted me in a

positive manner

- Satisfactory

– Employee greeted me but not with great enthusiasm

- Poor

– Employee was distracted and did not acknowledge me

We also had three yes/no questions:

- Employee

treated me with respect

- Employee

avoided jargon or technical language

- Employee

went the extra mile

Because the yes/no questions were quite subjective, we

discussed them extensively in the training and provided guidelines for what

should be expected from the Libraries service staff. We also conducted

role-playing and asked the shoppers to evaluate the mock transaction in order

to prepare them better for the actual experience. Space for additional comments

was also included and comments were encouraged

We sought to make the assessment as “real life” and

anonymous as possible. We informed staff in the departments to be studied that

the exercise would take place sometime during the semester. We did not,

however, give exact dates. We met with each department to apprise them of the protocol

and assure them it was not part of their performance review but rather an

overall assessment of our service so that we could address any issues

identified. To that end we did not include any date/time stamps in the results.

The questions developed for the survey were constructed around the feedback

received from the initial LibQual+® results that indicated some patrons did not

feel they were treated respectfully by staff. We collaborated with the heads of

the ROI, Access Services and Schiffman Music Library to obtain frequently asked

questions considered “typical.” Questions for the Checkout Desk emphasized

service-related questions that could usually be answered with basic responses,

such as: “how many books can I check out at one time?” or “where can I print

something in color?” While certain categories of service related questions may

seem easy to answer we wanted to ensure that shoppers were being asked the

right clarifying questions by employees, not to see if the correct answer was

provided since that was not the primary focus of this study. For example, it

would be simple to tell a questioner that the library is open 24 hours, 5 days

a week but, in reality, that schedule is only applicable to people with a UNCG

ID. For other patrons, the library closes at 12:00 AM.

For questions to be asked at the Reference Desk, the

head of the ROI provided a list of questions relating to common assignments and

citation issues. Since often times the Reference Desk is staffed by

paraprofessional staff, we did not want to present a difficult question that

would require obtaining additional assistance, or place the questioner in a

position which would require him/her to handle questions they could not answer.

Examples of questions asked of Reference staff included: “can you help me find

articles on identity theft?” and “I am a UNCG graduate, how do I access the

databases from home?” or “How to do cite this in APA style?” (See Appendix 2

for sample questions).

We required the shoppers to attend a 90-minute

training session. During the training, we provided an explanation of the

importance of excellent customer service to the Libraries as well as the

customer service values (and behavioural examples of them) that staff were

expected to demonstrate, and we provided instruction on what to look for when

observing staff behaviours. Each shopper was assigned a question for each

service point (Reference Desk, Access Services Desk and the Schiffman Music

Library) and type of service (in-person, telephone and chat) with the exception

of the Schiffman Music Library and Access Services; chat service was not

offered in Schiffman at the time of the initial survey and is still not

available in the Access Services department. We requested that shoppers vary

their times of contact to make their presence as anonymous and unobtrusive as

possible. We also wanted to vary the time of contact to avoid staff members

feeling as if they were being “targeted” if the questions were only asked

during specific time periods.

One question was placed on each rating sheet used by

the shoppers. Six students completed the exercise with each shopper asking a

question for each service. They entered their scores into a Qualtrics® form

created by the team. Qualtrics is an online survey platform licensed on many

campuses. They also submitted paper sheets as a backup.

Results

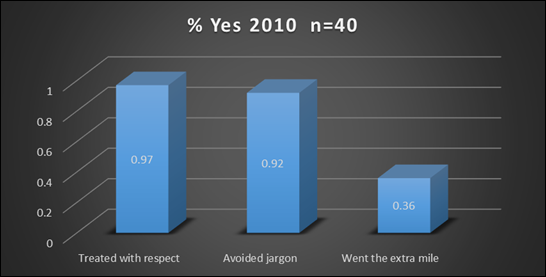

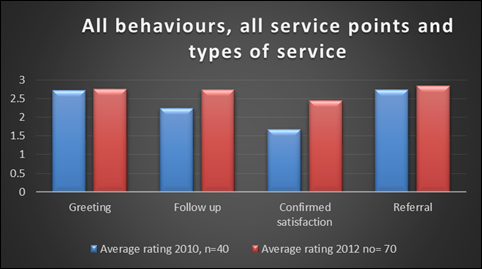

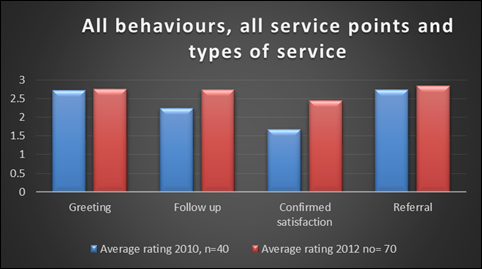

For the most part, the Libraries received very

positive results. Scores were particularly high for “greeting” and “referral.” “Follow-up”

was rated slightly less well and “Confirming satisfaction” the lowest. For the

Yes/No questions, shoppers rated staff well for “Treated with respect” and

“Avoided jargon.” There were, however, issues with “Going the extra mile.”

Below are overall averages for all service points and types of service (Figures

1 and 2).

We also compiled results for each department broken

down by type of service (Figure 3).

Follow Up

The Assessment Analyst compiled the results and

developed graphs for each question that indicated scores for desk, phone, and

chat. The results for all services were shared with the entire staff through

meetings and email. The Associate Dean shared results for individual

departments with the appropriate department head for discussion among their

staff. After examining the results, the team had the following recommendations:

- Develop

“standards of service” that reflect the customer service values. Although

we had the values we really had no specific standards or guidelines for

interacting with staff. For example, we did not have guidelines on how to

greet patrons, do a referral, transfer a phone call to another department,

or best practices for chat service. Established standards are useful to

train new staff, both full-time and student employees, so that they know

what is expected of them. As our public service

desks are

staffed by a variety of employees, we determined it was important to establish

service standards that would be uniform across all service points to ensure a

more consistent experience for users. These standards are based on both

industry best practices and library staff input. They include not only

procedural guidelines but also advice on how to “go the extra mile” which is

subjective in nature and can be difficult to define. Advice here includes “walk

a patron to a destination rather pointing them, including going to the stacks”,

“feel empowered to be flexible in order to provide service”, and “be flexible

about staying after hours to provide a consultation for a student who works

full time”. These standards are posted on the Customer Service Skills LibGuide

under the “Customer Service Documents” tab (UNCG University Libraries, 2015b).

- Develop

customer service training for full-time library staff that focused on

“going the extra mile.” The impetus for this was the feedback from users

during the LibQual +® results. While the phrase “going the

extra mile” is subjective and varies according to the individual being

asked, we wanted to convey to staff members that being polite and helpful

was not enough. We felt it was important for all staff members to ask

enough questions and offer a level of assistance to ensure that all user

needs were being met. Because that question received lower scores we

decided that we needed the opportunity to discuss what we meant by going

the extra mile and how we could achieve it.

- Develop

online training for student employees. Because our students work many

shifts in two buildings it is impossible to get them all together for

training.

- Conduct

the assessment again after training to see if there was improvement.

Figure 1

Results for the “four behaviours” questions.

Figure 2

Results for the YES/NO questions.

Figure 3

Results by type of service.

Staff Training

Training was provided for all library staff members

including those that did not have contact with the public. We wanted to ensure

that the customer service values we wanted to impart within the library were

given to staff members that provided internal service, not just given to those

who work at public services desks.

We conducted six sessions (4 hours each, with breaks)

and extended an offer to attend training to the managers of the computer labs,

which are housed in the library but are not under the organizational control of

the library. Because the lab is located in the library, students often make an

incorrect connection between the computing lab staff and the library staff. The

managers of the computer labs were unable to attend, however. Sessions were

staggered so that those staff members that work during evening hours were able

to attend. All employees of the library, with the exception of the Dean and the

Assistant Deans, were required to attend the sessions. Approximately 90% of the

staff, including library faculty completed the training.

The training design was done by the Human Resources

Librarian. She also conducted the training sessions, and developed a workbook

to use in the training sessions. The program design focused on “Going the Extra

Mile” which the team felt would allow the staff not to feel the training was

remedial in nature or was being used as a punitive measure. The emphasis in the

program design was to improve customer service and eliminate the feeling by patrons

that they were not being treated respectfully. We were careful to point out

that the LibQual+® scores reflected that good customer service was being

provided. We let the staff know that the LibQual+® qualitative data included

comments which said some respondents did not feel the customer service being

provided went far enough; it did not “go the extra mile.”

Although not planned, the training sessions gave some

staff members new information about some of the services offered within the

library; staff members who are considered to be internal service providers

found the information to be extremely beneficial. The Libraries’ customer

service values were updated based on staff suggestions.

Student Training

As mentioned above we determined that online training was best for our student

employees. The Libraries place great emphasis on providing our students with

the opportunity to gain skills they can use in the future regardless of what

profession they chose. The Distance Education Librarian and a Library and

Information Studies (LIS) practicum student spent a semester developing

customer service videos around the standards. These include basic skills such

as approachability, the reference interview, telephone etiquette, referrals and

handling a line of customers. Additional videos provide tips for dealing with

angry customers. We used students in the videos and made them upbeat and

humorous so that they would appeal to our employees. Libraries’ documents such

as the customer service values and standards are included as well. The videos

and documents were organized into a LibGuide for easy access and editing (UNCG University Libraries, 2015b). Once the LibGuide was completed, student supervisors asked to include

videos on general basic success skills such as attitude, attire, and

professional image. For these segments we pulled videos from our Films on Demand subscription. Student

supervisors were asked to require employees to view the videos and make

comments to indicate they had completed them. Some comments from students

include:

- “These

skills seem like common sense, but it's amazing how many people you see

that don't follow it. You should send this video to the workers in

Subway.”

- “I

easily get flustered when a person is frustrated at me, however this video

taught me how to properly handle the situation and remain calm and

respectful”

- I’ve

never thought to look for people who need help because I always assumed

they would ask, now I know.”

Second Study

In the second mystery shopping assessment, staff

members were again told that mystery shopping would happen sometime during the

spring semester, but were not given a specific timeframe. During the second

study, we reached out again to the Department of Hospitality and Tourism

Management for students to be mystery shoppers and recruited nine students. We

reviewed the questions and made some minor changes to them. Because our Special

Collections and Archives (SCUA) had added a formal service point it was

included in the assessment and questions for that area were added. For this

study an LIS graduate student assisted us. She helped with the training

sessions, prepared the question sheets, and entered data into Qualtrics.

The same training was provided for the second group of

secret shoppers that was provided for the first group of shoppers. As with the

first group of student shoppers, we explained the importance that the library

placed on customer service and that we were assessing the customer service

experience rather than accuracy of the answers. We shared the newly developed

Standards of Service as well as the Customer Service Values.

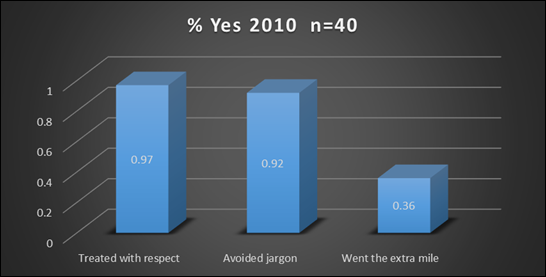

Results from the 2012 assessment indicate that

improvement occurred for all behaviours and questions from the 2010 results

(Figures 4 and 5).

We were particularly glad to see that the areas with

the lowest scores in 2010, “follow up” (increase from 2.24 to 2.73), “confirmed

satisfaction” (increase from 1.68 to 2.44 out of 3) and “went the extra mile,”

had the largest margin of improvement. In 2010 only 36% of respondents felt

that their service went the extra mile; in 2012 that rose to 59%.

.

Figure 4

Results for ‘four behaviour’ questions, 2012.

Figure 5

Results for YES/NO questions, 2012.

We shared the overall results again with all

Libraries’ staff and posted comparison graphs on our assessment LibGuide.

Similar graphs for each department were also developed

and shared with the department heads. The Associate Dean discussed results in a

Public Services Department Heads meeting and individually with department

heads. She also visited department meetings to discuss the results with staff

and gain their input. We also shared results with student employees during the

fall 2012 student orientation to show returning students the improvement in

their performance and to let new students know that the online training is very

important information.

Discussion

The Libraries conducted LibQual+® again in fall 2012

with an increase in the “Affect of Service” score from 7.5 in 2008 to 7.92.

These results, along with changes between the 2010 and 2012 mystery shopper

results, indicate substantial improvements in service quality and satisfaction

for the Libraries. Developing standards and providing training reinforced the

importance of customer service and the role that all staff members play so that

users have a positive experience in the library. Staff comments received after

the training indicate that the training was helpful and resulted in staff members

viewing customer service and their own role as service providers in a different

way; a role which is key to having a positive experience in the library. The

Libraries continue to emphasize the importance of customer service. All new

staff receive the customer service values and standards and are strongly

encouraged to attend appropriate campus workshops conducted by the campus Human

Resources Department to enhance their customer service skills. All new student

employees are required to complete the videos on the Customer Service

LibGuide.

We also continue to examine our services to ensure we

are meeting the needs of our patrons. Because we are likely to continue

staffing with paraprofessionals, future customer service training should

include not only going the extra mile, but also providing the skills and

knowledge to answer questions accurately. While providing helpful, respectful,

and courteous service is a requirement, we recognize that our training needs

will shift also to enhancing skill development. Examples would include

conducting reference interviews and ensuring competence with the wide variety

of resources for those staffing the service desks. Training will also need to

take into account the changing demographics of our customers. For example, we

have an increasing number of international students, as well as larger numbers

of what would be considered to be “adult students.” As our requests for virtual

reference assistance increase, we anticipate that chat inquiries will also

become more complex. As mentioned above, our services must respond to changes

in academic libraries and higher education and we need to ensure that

assessments correspond accordingly.

Conclusion

The mystery shopper exercises provided the UNCG

University Libraries with the opportunity to examine our services and customer

service goals more closely. The changing nature of our services with moving

toward using more paraprofessional staff and the impact of technology on

services provided some of the impetus for doing the study. We also wanted to

gather additional evidence on issues identified in the 2008 LibQual+ ®survey.

And finally, we sought more in-depth assessment of the user experience than that

provided by satisfaction measures.

Conducting the mystery shopper study identified

several areas to address. We realized we needed more clearly defined standards

for staff to follow. We saw that we needed to discuss what “going the extra

mile” means to us as an organization. We also needed to develop a scalable

training method for student employees. Although our research design and methods

did not include tests for validity, the results strongly suggest that standards

and training had a positive impact on improvement. It was also very useful to

have specific evidence for staff to see where changes needed to be made. And it

was equally important to celebrate with staff when there was improvement! The

study provided an excellent opportunity for the Libraries’ staff to discuss

what service means to us as an organization and helped enhance the already

established culture of excellent customer service.

It is essential to get buy-in from staff before

conducting a mystery shopper study and make the goals of the study clear and

transparent. For some staff it may always be perceived as a threat and

management needs to assure them that such assessment is necessary in order for

the library to remain viable and current and to ensure that we are providing

the services and resources that our customers need and desire.

References

ACRL (2012) Top ten trends in academic libraries.

(2012). College & Research Libraries News, 73(6), 311-320.

Retrieved from http://crln.acrl.org/

Andruss, P. (2010). The case of the missing research

insights. Marketing News, 44(7), 23-25.

Backs, S. M., & Kinder, T. (2007). Secret shopping

at the Monroe County Public Library. Indiana Libraries, 26(4),

17-19.

Bell, S J. (2011, March). Delivering

a WOW user experience: do academic librarians measure up? Paper presented

at the biennial meeting of the Association of College and Research Libraries,

Philadelphia, PA. Retrieved from http://www.ala.org/acrl/conferences/confsandpreconfs/national/acrl2011papers.

Bell, S. J. (2014). Staying true to the core: designing the future

academic library experience. Portal: Libraries and the Academy, 14(3), 369–382. http://dx.doi.org/10.1353/pla.2014.0021

Benjes-Small, C., & Kocevar-Weidinger, E. (2011).

Secrets to successful mystery shopping: A case study. College & Research

Libraries News, 72(5), 274-287. Retrieved from http://crln.acrl.org/

Cocheo, S. (2011). Mystery shop the whole bank. ABA

Banking Journal, 103(1), 13.

Connaway, L. S., Dickey, T. J., & Radford, M. L.

(2011). “If it is too inconvenient I'm not going after it”: Convenience as a

critical factor in information-seeking behaviors. Library & Information Science Research, 33(3), 179-190. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.lisr.2010.12.002

Czopek, V. (1998). Using mystery shoppers to evaluate

customer service in the public library. Public Libraries, 37(6),

370-375. .

Deane, G. (2003). Bridging the value gap: Getting past

professional values to customer value in the public library. Public

Libraries, 42(5), 315-319. Retrieved from http://www.ala.org/pla/publications/publiclibraries

Foster, N. F., & Gibbons, S., (2007). Studying students: The

undergraduate research project at the University of Rochester. Chicago, IL:

Association of College and Research Libraries.

Foster, N. F. (Ed.) (2013). Studying students: A second look.

Chicago, IL: Association of College and Research Libraries.

Fox, R. & Doshi, A. (2011). Library user experience. ARL Spec

Kit 332. Washington, DC: Association of Research Libraries.

Gavillet, E. L. (2011). The “just do it” approach to

customer service development: A case study. College & Research Libraries

News, 72(4), 229-236. Retrieved from http://crln.acrl.org/

Hammill, S. J. & Fojo, E. (2013). Using secret

shopping to assess student assistant training. Reference Services Review, 41(3),

514-531. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/RSR-12-2012-0086

Hernon, P., Nitecki, D. A., & Altman, E. (1999). Service quality and

customer satisfaction: An assessment and future directions. Journal of

Academic Librarianship, 25(1), 9-17. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0099-1333(99)80170-0

Kocevar-Weidinger, E., Benjes-Small, C., Ackermann,

E., & Kinman, V. R. (2010). Why and how to mystery shop your reference

desk. Reference Services Review, 38(1), 28-43. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/00907321011020707

Peters, K. (2011). Office Depot's president on how "mystery

shopping" helped spark a turnaround. Harvard Business Review, 89(11),

47-50. Retrieved from https://hbr.org/

Roy, L., Bolfing, T., & Brzozowski, B. (2010).

Computer classes for job seekers: LIS students team with public Librarians to

extend public services. Public Library Quarterly, 29(3), 193-209,

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01616846.2010.502028 .

Tesdell, K. (2000). Evaluating public library

service—the mystery shopper approach. Public Libraries, 39(3),

145.

Tierney, J. (2012, February 2). Nine merchants earn

top marks in online customer service study. Multichannel

Merchant Exclusive Insight. Retrieved from

http://multichannelmerchant.com/ecommerce/nine-merchants-earn-top-marks-in-online-customer-service-study-02022012/

UNCG University Libraries (2015a). Mission statement,

goals and values. Retrieved from http://library.uncg.edu/info/mission_statement.aspx

UNCG University Libraries (2015b). Customer service

skills. Retrieved from http://uncg.libguides.com/customerservice

UNCG University Libraries (2016) Assessment

information. Retrieved from http://uncg.libguides.com/libassessment

Appendix A

Mystery Shopper Questions

|

Access Services

|

Music

|

Reference (now Research Outreach and Instruction)

|

Special Collections and Archives (SCUA)

|

|

What are your hours today?

|

I just heard a symphony called Witches Sabbath. Do

you have a recording of this on CD?

|

When were presidents only serving two terms and what

law was that?

|

How many books can I check out at one time?

|

|

I’m in a wheelchair and I want to come to the

library? Where can I park and how to I get into the building?

|

I’m not a music student, but I need biographical

info on Stravinsky for my Russian History class. Can you help me?

|

I need to research the gaming industry.

|

I’d like to donate some books to the library. Who

can I talk to about this?

|

|

I would like to check out an iPad. How long can I

keep it and what downloads can I put on it?

|

What are your hours today?

|

I’m researching the travel industry as a possible

career. Where can I look?

|

I’m looking at your homepage, and I came across the

term “finding aid.” What is that? How do I use it in my planned research?

|

|

How long can I check out items?

|

I need to fax something. Can I do that here?

|

I’m supposed to find some blues music for my African

American history class. Is there something I can find online?

|

Can I scan something in the library?

|

|

I need to change my UNCG password. Where can I do

that?

|

I’d like this CD please.

|

I need to fax something. Can I do that here?

|

Can I check out materials from Special Collections

and University Archives? Do you have your policies posted online? If so, can

you show me where they are on the Library site?

|

|

Is there a place I can meet my group in the library?

|

Do you take donations of LP’s?

|

I need to find financial information about the

Hilton hotel chain.

|

What are your hours today?

|

|

I need to make a color print. Where can I do that?

|

Do you have a score of Beethoven’s Eroica symphony?

|

I’m looking for an article from the NATS journal

from 1994 and I can’t find it online.

|

When did UNCG change from being a women’s college to

a co-ed university?

|

|

I need help with my laptop. Where can I go?

|

How long can I check out items?

|

I need to cite this article in APA citation style.

|

My grandmother graduated in 1945; I’d like to find

her picture in the yearbook.

|

|

How do I renew my books?

|

I’m looking for a recording of “Alexander’s Ragtime

Band” to use for an American Social History class. Is there a way I can get

that online?

|

Which Supreme Court justice has been on the Court

the longest and who appointed him or her?

|

My family has a large collection of old papers that

seem to be related to Greensboro and UNCG.

|

|

Can I scan something in the library?

|

I need to find a recording of “Brahms Requiem.” I’m

not a music student. Can I check out the CD?

|

I need some films on how to prepare for a job

interview.

|

I am completing a research paper for a history

class. I used your University archives collection. Is there a specific way to

cite my sources?

|

Appendix B

Mystery Shopper

Rating Sheet

![]() 2016 Crowe and Bradshaw. This is an Open

Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

2016 Crowe and Bradshaw. This is an Open

Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.