Contextual Introduction

The search for a

robust approach for catalyzing organizational learning experiences arose in

2003 within a North American academic library experiencing unprecedented

changes and persistent uncertainty. Volatile forces within the scholarly

ecosystem had irrevocably altered traditional relationships among researchers,

librarians, publishers, and vendors (Somerville, Schader, & Sack, 2012;

Somerville & Conrad, 2013; 2014), requiring new workflows and workplace

competencies. In addition, changing

pedagogical practices and new business models in higher education (e.g.,

Coaldrake & Stedman, 2013; Crow & Dabars, 2015) necessitated redesigning facilities,

reconsidering collections, and reinventing services. These converging forces

required that staff members learn to see their organizations and understand

their roles in new ways because “library services in higher education will

continue to be crucial to the core processes of learning, teaching, and

research as long as the key library structures, processes, services, and staff

roles evolve to accommodate epochal changes occurring in publishing and

communications” (Wawrzaszek &

Wedaman, 2008, p. 2).

More than a decade

later, unrelenting disruptions in both higher education and scholarly

communication ecosystems continue, fundamentally challenging traditional

assumptions about academic library roles, responsibilities, services, and facilities. As

a consequence, academic librarians around the globe are asking:

- How could

the library organization better reflect the

vision of the

institution of which it is a

part?

- How could the library and its collections, services, and

spaces best serve the institution?

- How do library

outcomes add value to

the academic experiences of

students and faculty?

- How might the

library function more interdependently with

other campus learning and

teaching activities?

- What programs not

in the library at present should be in the

facility in

the future? (Lippincott,

2014; Hemmasi, Lefebvre, Lippincott, Murray-Rust, & Somerville,

2015).

Such enterprise level

questions hold considerable promise for catalyzing constituent engagement,

creating shared vision, and building stakeholder partnerships. Their profound

importance in forging vital new directions underscores the inadequacy of

reliance on mere ‘busyness’ statistics, such as gate counts and PDF downloads,

for evidence.

Rather, “systemic changes require systemic responses because a case-by-case or

incident-by-incident response was inadequate, given the magnitude of

transformation underway” (Somerville, 2015, p. 45). In response, Informed

Systems – which integrates complementary information- and learning-focused

theories – addresses a research-in-practice problem – i.e., the lack of an

integrated model to inform workplace learning in contemporary information and

knowledge organizations.

The Informed Systems

approach supports evidence based professional activities to make decisions and

take actions. It enables co-workers to make informed decisions by identifying

the decisions to be made and the information required for those decisions. This

is accomplished through collaborative design and iterative evaluation of

workplace systems, relationships, and practices. Over time and with experience,

increasingly effective and efficient structures and processes for using

information to learn advance organizational renewal and nimble responsiveness

amidst dynamically changing circumstances.

Informed Systems

principles and practices exercise and enable participatory design, action

learning, and perpetual inquiry through “using information to learn” (Bruce,

2008) in ever expanding professional situations. A persistent focus on

cultivating rich information experiences through information-centered and

action-oriented dialogue and reflection serves to advance information exchange

and knowledge creation, through which transferable learning occurs and organizational

capacity builds (Somerville, Mirijamdotter, Bruce, & Farner, 2014). This conceptual

paper presents systemic activity and process models that activate collaborative

evidence based information processes within enabling conditions for thought leadership

and workplace learning.

Antecedent Thought

This integrated

approach to fostering persistent workplace inquiry has its genesis in three

theories that together activate and enable robust information usage and organizational

learning. The information- and learning-intensive theories of Peter Checkland

in England, which advance systems design, stimulate participants’ appreciation

during the design process of the potential for using information to learn

(Checkland & Holwell, 1998). Within a co-designed environment, intentional

social practices continue workplace learning, described by Christine Bruce in

Australia as informed learning (Bruce, 2008) enacted through information

experiences (Bruce, Davis, Hughes, Partridge, & Stoodley, 2014). In

combination, these theorists promote the kind

of learning made possible through evolving and transferable capacity to use

information to learn through design and

usage of collaborative communication systems with associated professional

practices.

In addition, in Japan,

Ikujiro Nonaka’s theories foster information exchange processes and knowledge

creation activities within and across organizational units. An organization is

thereby considered a knowledge ecosystem consisting of a complex set of

interactions between people, process, technology, and content. Knowledge

emerges through exchange of resources, ideas, and experiences through which

individual knowledge becomes corporate knowledge (Nonaka, 1994). This “knowledge-related work requires thinking – not

only monitoring, browsing, searching, selecting, finding, recognizing, sifting,

sorting and manipulating but also being creative, always questioning,

interpreting, understanding situations…with particular focus on how to put questions,

draw inferences, give explanations and conclusions, prioritize” (Materska,

2013, p. 231) within increasingly complex and ever-changing environments.

Stated differently,

Informed Systems learning outcomes emerge through integration of multi-disciplinary

theory from around the world. According to Checkland’s Soft Systems Methodology

(SSM), learning emerges through collaborative design of organizational systems

and professional practices (Checkland & Scholes, 1990; Checkland &

Poulter, 2010). In a complementary fashion, Bruce recognizes that collective

understanding advances through intentional use of information to learn in the

workplace (i.e., Bruce, 1997; 1998; 1999; 2008; 2015), while Nonaka emphasizes

the possibilities for social knowledge creation within workplace environments

(Nonaka, 1994; Nonaka & Takeuchi, 1995; Von Krogh, Ichijo, & Nonaka, 2000; Nonaka, Konno, &

Toyama, 2000; Nonaka & Toyama, 2007). In a highly synergistic fashion,

these antecedent ideas have, in combination, informed the evolution of models

for enabling and enacting collaborative evidence based decision-making, both

creating requisite conditions and guiding learning processes. At its essence,

Informed Systems recognizes that when information is managed effectively, it

facilitates collaboration among co-workers that furthers decision-making and

advances organizational learning based on that information (Chatzipanagiotou,

2015).

Since 2003, Informed Systems evolved to foster information exchange,

reflective dialogue, knowledge creation, and conceptual change. Results from

evaluative studies (e.g., Somerville, Schader, & Huston, 2005; Somerville,

Rogers, Mirijamdotter, & Partridge, 2007; Somerville, 2009; Mirijamdotter

& Somerville, 2009; Somerville, 2015) reveal that, over time and with

practice, this collaborative learning approach progresses co-workers’ capacity

for creating systems and producing knowledge, activated by participatory

design, amplified by systems thinking, and exercised by informed learning. In

“working together” (Somerville, 2009) to generate knowledge, colleagues

contribute complementary knowledge skills, work responsibilities, and social

statuses which advance social, relational, and interactive aspects of work life

(Townsend, 2014). Capacity builds through using information to learn in ever

expanding professional contexts that exercise evidence based decision-making

and action-taking.

Approach Fundamentals

Research-in-practice

project results from 2003 to 2006 at California Polytechnic State University in

San Luis Obispo (e.g., Mirijamdotter & Somerville, 2009; Somerville, 2009)

and at the University of Colorado in Denver from 2008 through 2015 (e.g.,

Somerville & Howard, 2010; Somerville & Mirijamdotter, 2014;

Somerville, 2015) demonstrate the efficacy of cultivating informed learning

experiences within enabling, co-designed workplace systems. After considerable

dialogue and reflection among the international research team, Somerville,

Mirijadmotter, and Bruce, the approach was named Informed Systems in 2012 and

introduced in a multi-author book on international information experience in

2014 (Somerville & Mirijamdotter, 2014).

In California, some

early principles for workplace leadership emerged from pilot projects. These

elements recognize the recursive nature of systems perspectives and knowledge

practices for workplace leadership that aims to further organizational

learning.

- Integral to creation of a robust learning

organization, leaders are responsible for design of workplace environments

supportive of information-rich conversations.

- Systems thinking can be used to contextualize

workplace issues in terms that revisit both the nature of organizational

information and the purpose of organizational work.

- It follows that as leaders apply systems thinking

methodologies and tools to understand the complexities of the organization

and its situation, staff members learn to diagnose problems, identify

consequences, and make informed responses within a holistic context

(Somerville, Schader, & Huston, 2005, pp. 222-223).

Evaluative results

from this early development work demonstrate that application of these

principles changes how co-workers think and what they think about.

- More specifically, individuals see the underlying

context and assumptions for their decision. This new relational

understanding predisposes them to adjust their assumptions and strategies

as they learn – in other words, as they change appreciative settings.

- Over time and with practice, individuals’

adoption of systems thinking and thinking tools provides a collective

strategy for successfully responding to new information and unique

situations.

- And, finally, sustained conversations rich in

relational context provide the substance of a robust organizational

learning environment. This dialogue has transformative potential when it

activates and extends prior learning (Somerville, Schader, & Huston,

2005, p. 223).

Building upon this foundation, University of Colorado Denver leadership activities

focused on exercising and elaborating informed learning capacities as

transferable outcomes of “using information to learn” (Bruce, 2008) within

Informed Systems. These capabilities were catalyzed during organizational

systems design and extended through professional workplace practices, and

include:

- Information and

communication technologies to harness technology for information and

knowledge retrieval, communication, and management,

- Information sources and

information experiences to use information sources (including people) for

workplace learning and action-taking,

- Information and

knowledge generation processes to develop personal practices for finding

and using information for novel situations,

- Information curation

and knowledge management to organize and manage data, information, and

knowledge for future professional needs,

- Knowledge construction

and worldview transformation to build new knowledge through discovery,

evaluation, discernment, and application,

- Collegial sharing and

knowledge extension to exercise and extend professional practices and

knowledge bases which generate workplace insights and informed decisions,

and

- Professional wisdom and

workplace learning to contribute to collegial learning, using information

to learn to better take action to improve (Bruce, Hughes, &

Somerville, 2012).

In recognition of the requisite conditions for furthering these essential

elements, Informed Systems models foster boundary-crossing knowledge creation

and systems-enabled knowledge management in the workplace.

Knowledge

processes assume that people can learn

to create knowledge on the basis of their concrete experiences, through

observing and reflecting on that experience, by forming abstract concepts and

generalizations, and by testing the implications of these concepts in new

situations. Process-based learning activities lead to new concrete experience

that initiates a new cycle. It follows that reflective practitioners learn

through critical (and self-critical) collaborative inquiry processes that

foster individual self-evaluation, collective problem-formulation, and

inclusive active inquiry (Somerville & Mirijamdotter, 2014, p. 206).

Learning the way to

action-taking thereby advances when participants have increasingly more complex

experiences of information exchange, sense making, and knowledge creation, well

supported by workplace communication systems and professional practices,

further dialogue and reflection and thereby enrich analysis and interpretation

of complexities and interdependencies. It naturally follows that learning is a

socio-cultural process that cultivates “resilient

workers” (Lloyd, 2013) as, over time and with practice, co-workers design and

enact information-focused and evidence based learning experiences.

Learning Essentials

Within Informed

Systems, the working definition for a learning organization is “a purposeful

social interaction system in which collective information experiences are

fostered by professional information practices to bring about change in

organizational awareness and behavior and thereby further knowledge creation

processes” (Somerville, 2015, p. 49). Within such a ‘whole systems’ framework,

organizational leadership must establish and embed sustainable social

interactions and enabling workplace systems that can successfully determine:

“What information…experiences do we want to facilitate or make possible? What

information and learning experiences are vital to further our…professional

work?” (Bruce, 2013, p. 20).

Within this framework,

co-workers gain progressive insight into nuanced dimensions of using

information to learn through exploring such questions as these: “What

constitutes information?…What is being learned? How is understanding/experience

of the world changing? What can we do to enrich informed learning

experiences?…to introduce new experiences? How would…range of experiences, and

awareness of these experiences, be demonstrated?” (Bruce, 2012, n.p.).

In addition to

consideration of experiential dimensions of workplace information, the Informed

Systems learning approach recognizes that assumptions and conclusions,

including norms and values on which collective judgements are based, is the

result of previous individual, group, and organizational experiences and

history. So explicit reflective practices are designed to promote individual

and group awareness of tacit thinking and reasoning. Questions for making

thinking visible include: “What is the observable data behind that statement?

Does everyone agree on what the data is?…How did you get from that data to

these abstract assumptions? When you said ‘[your inference]’, did you mean ‘[my

interpretation of it]?” (Senge, 1994, p. 245). Such workplace practices

encourage individuals and groups to reconsider and reframe thinking, feeling,

and responding.

Improved understanding

occurs because “the knowledge that individuals and organizations have of

themselves provides the framework in which they choose alternatives from among

a huge, often unaccountable, range of possibilities” (Leonard, 1999, n.p.).

Self-knowledge is also mediated by the culture and language in which

discussions take place and the extent to which it is possible to integrate

various perspectives. Informed Systems models, therefore, guide participants in

moving beyond surface topics to explore deeper issues through reflective

inquiry and collaborative action (Somerville, 2015). Taking action to improve

then produces changes in the ways of perceiving and of becoming newly aware and

thereby learning.

Enactment of workplace

learning requires an enabling environment for information exchange, sense

making, and knowledge creation activities that advance information use and

learning relationships through socio-cultural processes and practices

co-designed by co-workers. Collective capacity for discussion and analysis of

complexities and interdependencies grows through intentional construction and

reconstruction of the learner during interactive relationships and sustainable

networks comprised of information, technology, and people. Such “construction

of learning, of learners and of the environments in which they operate” (Hager,

2004, p. 12) evolve to adopt and

adapt, create and recreate, contextualize and re-contextualize through

wider and wider circles of consultation, cooperation, and collaboration.

Viewed through an

information experience lens, colleagues collectively expand the information

horizons of their work environments through wider and wider circles of

consultation, cooperation, and collaboration. While engaging with new

information types and communication processes, they establish productive

information-sharing relationships which extend beyond team boundaries through

critical and creative information use and through generation and sharing of new

knowledge necessary to taking purposeful action (Somerville & Mirjamdotter,

2014). Informed Systems

thereby offers models for (re)learning processes, conducted within enabling

systems infrastructure for collaborative evidence based information practice.

Collaborative Evidence-based Information

Process Model

An inquiry-intensive

and evidence based Informed Systems workplace requires significant attention to

both process and content. While exploration of peer-reviewed publications

oftentimes initiates evidence based practices, authoritative evidence may

include a wide range of information sources and professional knowledge.

Quantitative and qualitative research results, local statistics, open access

data, and even accumulated knowledge, opinion, relationships, and instinct may prove

useful, depending on local circumstances (Koufogiannakis, 2011; 2012; 2013a;

2013b; 2015).

Understanding that librarians use evidence to

convince, allows an entire organisation to proceed with this as a known entity,

and should enable that organisation to look more completely at what the

pertinent forms of evidence contribute to the decision, to weigh those pieces

of evidence, and to make a decision that is more transparent. The use of

evidence for convincing illustrates the complexity of decision-making,

particularly within academic libraries, and points to the fact that evidence

sources do not stand alone, and are not enough in and of themselves. The EBLIP

process must account for the human interactions, and organisational complexity

within which decisions are being made (Koufogiannakis, 2013a, p. 172).

A holistic workplace

approach therefore requires consideration of elements of organizational design

and professional practice essential to collaborative decision-making. This

includes fostering a culture of well elaborated organizational processes and

knowledge practices (Somerville, Rogers, Mirijamdotter, & Partridge, 2007;

Pan & Howard, 2009; 2010; Mirjamdotter, 2010; Somerville & Howard,

2010; Somerville & Farner, 2012; Somerville, 2013; Howard & Somerville,

2014). Evidence based learning processes are also necessarily collegial,

conducted within a positive work environment, and enabled by appropriate

processes for open discussions for decision-making and action-taking.

“Knowledge and understanding are thereby learned through active…practice by an

individual, within the larger body of practice” (Schön, 1983, p. 50), which

situates and contextualizes intersubjectively created meaning and changes over

time through renegotiation.

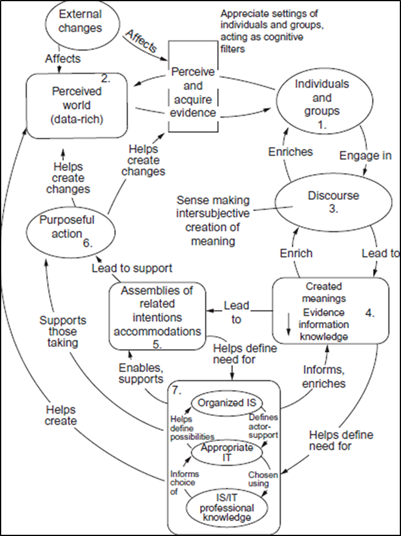

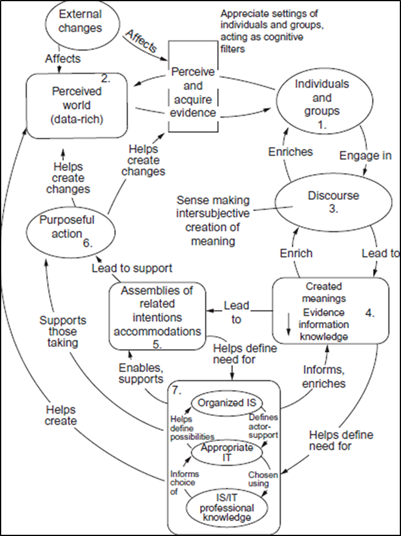

The Collaborative Evidence-Based

Information Process Model (Figure 1) delineates these collaborative processes

that advance using information to learn through interactive relationships

between the organizational context (elements 1-5), in which individuals and

groups create meanings and intentions, which leads to purposeful action

(element 6) being taken, with the support of information transfer and knowledge

generation systems (element 7).

Figure 1

Collaborative

Evidence-Based Information Process Model

Note. Adapted from: Checkland, P., & Holwell, S. (1998). Information, systems, and information

systems: Making sense of the field, p. 106. Chichester, England: John Wiley

& Sons. Reprinted with permission from John Wiley & Sons.

Published in: Somerville, M. M. (2015). Informed systems: Organizational design for

learning in action, p. 52. Oxford, England: Chandos Publishing. Reprinted

with permission from Chandos, an imprint of Elsevier.

The model recognizes

that individuals select information from the workplace (and extended)

environment based upon a worldview consisting of existing interests,

experience, and values. In other words, unless purposeful intervention occurs,

individual perception is highly selective and tends to reinforce existing

assumptions. So the first step in designing a sense making process for

organizational (re)learning is to initiate conscious reconsideration. Raising

awareness to stimulate re-thinking requires catalyzing the innate mental

processes that are performed tacitly, without individuals making conscious

decisions about what is being admitted for consideration, and can eventually

widen consideration about what assumptions to make or which data to select.

Elements 1 and 2

and the interaction between them involve selectively perceiving reality and

making judgments about it through filtering processes that influence what

individuals choose to mind and, consequently, use as perception and

interpretation filters. These dimensions of information experience are

negotiated through sense making processes, including dialogue and reflections

(element 3). Learning thereby emerges within the context of workplace vision and

shared assumptions, including cultural beliefs and associated interpretations

and workplace practices, as depicted in element 4.

Organized

information systems (IS) and appropriate information technology (IT), together

with information and information technology skills (element 7), further inform,

enrich, and enable learning. In this way, tacit assumptions represented in a

worldview are explicitly reconsidered in the light of emergent new norms and

values. Judgments evolve and are explicated among employees through dialogue,

which then become the bases for forming intentions (element 5) towards

particular actions to be carried out (element 6). As is characteristic in

systems models, the seven elements are seen as interacting, i.e., element 7

informs and enriches element 4, and it enables and supports element 5, even as

it helps to create the perceived world (element 2), including vision, values,

and practices (Somerville, Mirijamdotter, Bruce, & Farner, 2014).

Within this

systemic context, thought leaders and knowledge activists offer filters to select

what is important from available information models to expand individuals’

ability to understand and use information to learn (Nonaka, 1994). These

interventions are challenging because tacit knowledge “consists of mental

models, beliefs, and perspectives so ingrained that we take them for granted

and therefore cannot easily articulate them” (Nonaka, 2007, p. 165). However,

as “new explicit knowledge is shared throughout an organization, other

employees begin to internalize it – that is, they use it to broaden, extend,

and reframe their own tacit knowledge” (Nonaka, 2007, p. 166) through

“purposeful discourse focused on exploring, constructing meaning and validating

understanding” (Garrison, 2014, p. 147).

Informed Systems Leadership Model

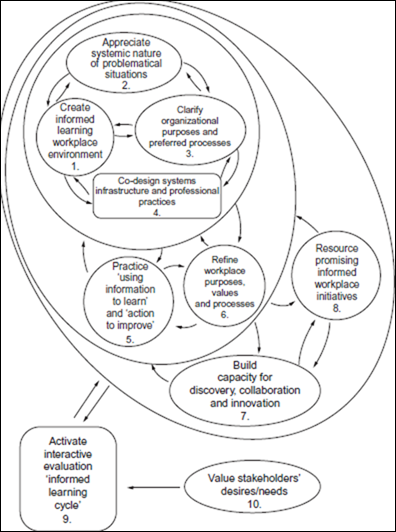

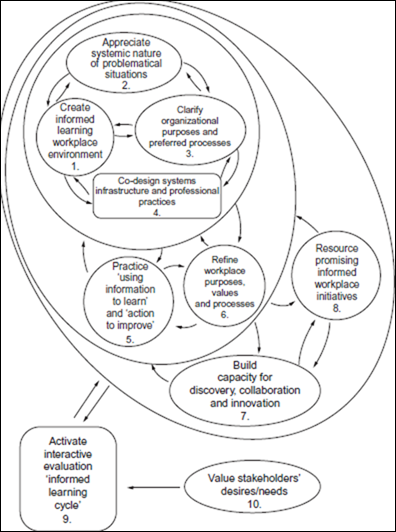

The Informed Systems Leadership Model identifies

essential elements for such organizational leadership, supported by

collaborative learning relationships that catalyze systemic outcome and process

evaluation cycles. This systems model visually represents purposeful activities

necessary to construct and sustain an environment that enables informed

learning experiences through informed leadership. The model presents activities

that together comprise processes for action and, ideally, for transformation

through high-level leadership activities.

Figure 2

Informed Systems Leadership Model

In this spirit, the model illustrates essential

aspects of workplace learning, enabled by design thinking. Activity 1

encourages collective exploration and, thereby, fosters robust learning. Its

centrality in the model reflects the conviction that contemporary organizations

cannot be managed in the traditional sense. Rather, co-workers should be

encouraged to actively engage in information exchange and knowledge creation

through using information to learn within enabling co-designed systems.

Activity 2 recommends appreciative inquiry and systems

thinking to advance understanding of organizational parts, their

interrelations, and their synergies. Emphasis on big picture and life affirming

understanding crosses organizational boundaries and bridges individual silos.

In the Informed Systems Leadership Model, this concept is reflected in

organizational vision, mission, values, and goals, which constitute Activity 3.

Activity 4 recognizes the critical importance of

enabling the expression and extension of thinking through purposefully

designed systems that connect people with ideas, oftentimes with technologies.

Such workplace infrastructure facilitates using information to learn and to

share, with the aspiration to generate collective knowledge reflective of

improved understanding.

Activity 5 acknowledges the significance of engaging

in collegial activities to improve professional practices and local situations.

Therefore, Activity 6 represents the importance of ongoing reflection and

dialogue to create continuous improvements in using information to learn how to

take action to improve situations. Activity 7 indicates that sustained movement

forward depends upon establishing strong learning relationships inside and

outside the organization. Organizational leaders are responsible for

coordinating and resourcing outcomes of Activities 1 through 7, as indicated in

Activity 8.

In order to nourish learning experiences and support

worldview maturation, Activity 9 recommends using interactive evaluation to

ensure responsive adaption. In this way, Activity 9 initiates a feedback cycle,

where performance can be monitored to inform modifications that anticipate

changes. In addition, Activity 10 acknowledges the importance of high-level

alignment of mission and vision with human and fiscal resources, negotiated within learning relationships exercised through action-oriented inquiry and inclusive decision-making

(Somerville, Mirijamdotter, Bruce, & Farner, 2014).

In combination, Informed Systems leadership and

collaboration models design enabling systems and informing activities that

cross professional and organizational boundaries through a strong “people

oriented” approach, customizable to local circumstances. It recognizes that

workplace learning originates from interactions and relationships among

organizational members, which enable investigation and negotiation of diverse

interests, judgments, and decisions. Reflection and dialogue processes promote

learning through critical (and self-critical) inquiry experiences that foster

individual self-evaluation, collective problem-formulation, and nuanced

professional development (Somerville & Mirijamdotter, 2014). Informed Systems

thereby promotes transformation in organizational awareness and workplace

behavior through intentional design that nurtures engagement among individuals

and with information.

Concluding Reflections

Contemporary organizations must develop workplace environments

that enable nimble decision-making and action-taking. In response, at the macro

level, Informed Systems models guide how and why organizations build knowledge

bases. At the micro level, design methodologies and learning theories guide how

and why co-workers use information to learn to co-create enabling systems and

evidence practices. Along the way, attention moves from transaction based

activities to organizational transformation outcomes enacted through intuiting,

interpreting, integrating, and institutionalizing knowledge together.

In response, Informed Systems appreciatively explores

the intersection of information, technology, and learning experiences in

organizational knowledge creation. Thought leaders create and refine

information activities that produce learning experiences and, over time and

with experience, advance integration of evidence based practice into workplace

culture, as detailed in the Informed Systems Leadership Model. Within this

enabling framework, a companion Collaboration Evidence-Based Information

Process Model guides collective decision-making and action-taking to ensure

perpetual learning and continuous improvement. As detailed in this conceptual

paper, these models illustrate the efficacy of integrating the work of three

theorists, Bruce, Checkland, and Nonaka, into a hybrid theory with an

associated methodology for workplace transformation.

Informed Systems results since 2003 demonstrate that

change, and ultimately transformation, occurs through using information to

learn. This depends on learning-centered and information-focused workplace

relationships fortified by professional practices that amplify evidence based

collaborative processes for decision-making and action-taking. Within this

organizational environment, colleagues learn to initiate inquiries and to

design experiences that are information-centered, evidence-grounded,

action-oriented, and learning-focused. Mental models and collective conceptions

change. Co-workers reinvent roles, responsibilities, processes, and

relationships, as they co-design potential futures.

References

Bruce, C. (1997). The seven faces

of information literacy. Blackwood, South Australia: Auslib Press.

Bruce, C. S. (1998). The phenomenon of information literacy. Higher Education Research & Development,

17(1), 25–43.

Bruce, C. S. (1999). Workplace experiences of information literacy. International Journal of Information

Management, 19(1), 33–47.

Bruce, C. S. (2008). Informed

learning. Chicago, IL: Association of College & Research Libraries/American

Library Association.

Bruce, C. S. (2012). Education, Research, and Information Services

workshop presentation, Auraria Library, Denver, Colorado. (Unpublished.)

Bruce, C. S. (2013). Keynote address. Information literacy research and

practice, an experiential perspective. In S. Kurbanoglu, E. Grassian, D.

Mizrachi, R. Catts, & S. Spiranec (Eds.), Communications in Computer and Information Science Series: 397.

Worldwide commonalities and challenges in information literacy research and practices:

European Conference on Information Literacy. Revised selected papers, (pp.

11–30). Heidelberg, NY: Springer.

Bruce, C. S. (2015). Information literacy: Understanding people’s

information and learning experiences. In Western

Balkan Information Literacy: Proceedings of the 12th International Scientific

Conference (pp. 11-16). Bihac,

Bosnia: Cantonal and University

Library Bihac.

Bruce, C., Partridge, H., Hughes, H., Davis, K., & Stoodley, I.

(Eds.). (2014). Information experience:

Approaches to theory and practice (pp.

203-220). (Library and Information Science, Vol. 9). Bingley, England:

Emerald.

Bruce, C. S., Hughes, H., & Somerville, M. M. (2012). Supporting informed learners in the

21st century. Library Trends,

60(3), 522-545.

Chatzipanagiotou, N. (2015). Toward

an integrated approach to information management: A literature review. 5th

International Conference on Integrated Information, Mykonos, Greece. Retrieved

from http://www.icininfo.net/index.php/program/submissions

Checkland, P. (2011). Autobiographical retrospections: Learning your way

to ‘action to improve’ - The development of soft systems thinking and soft

systems methodology. International

Journal of General Systems, 40(5),

487–512.

Checkland, P., & Holwell, S. (1998). Information, systems, and information systems: Making sense of the

field. Chichester, England: John Wiley & Sons Ltd.

Checkland, P., & Poulter, P. (2010). Soft systems methodology. In M.

Reynolds, & S. Holwell (Eds.), Systems

approaches to managing change: A practical guide (pp. 191–242). London,

England: The Open University, Published in Association with Springer-Verlag

London Limited.

Checkland, P., & Scholes, J. (1990).

Soft Systems Methodology

in action. Chichester,

England: John Wiley & Sons Ltd.

Coaldrake, P., & Stedman, L. (2013). Raising the stakes: Gambling with the future of universities. St.

Lucia, Queensland, Australia: University of Queensland Press.

Crow, M. M., & Dabars, W. B. (2015). Designing the new American university. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins

University Press.

Garrison, D. R. (2014). Community of inquiry. In D. Coghlan & M.

Brydon-Miller (Eds.), The SAGE

encyclopedia of action research. (Vol. 1, pp. 147-150). Los Angeles, CA:

SAGE Reference.

Hager, P. (2004). Conceptions of learning and understanding learning at

work. Studies in Continuing Education,

26(1), 3–177.

Hemmasi, H., Lefebvre, M., Lippincott, J., Murray-Rust, C., &

Somerville, M. M. (2015). Organizational

and service models. Designing Libraries for the 21st Century IV, North

Carolina State University, Raleigh, North Carolina, USA.

Howard, Z., & Somerville, M. M. (2014). A

comparative study of two design charrettes: Implications for codesign and

Participatory Action Research. Co-Design: International Journal of

CoCreation in Design and the Arts, 10(1), 46-62.

Hughes, H. (2014). Researching

information experience: Methodological snapshots. In C. Bruce, H. Partridge, H.

Hughes, K. Davis, & I. Stoodley (Eds.), Information

experience: Approaches to theory and practice. (pp. 33-50). Bingley,

England: Emerald.

Koufogiannakis, D. (2011). Considering the place of practice-based

evidence within Evidence Based Library and Information Practice (EBLIP). Library and Information Research, 35(111), 41-58.

Koufogiannakis, D. (2012). Academic librarians’ conception and use of

evidence sources in practice. Evidence

Based Library and Information Practice,

7(4), 5-24. Retrieved from https://ejournals.library.ualberta.ca/index.php/EBLIP

Koufogiannakis, D. (2013a). How

academic librarians use evidence in their decision making: Reconsidering the

evidence based practice model (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from http://cadair.aber.ac.uk/dspace/

Koufogiannakis, D. (2013b). Academic librarians use evidence for

convincing: A qualitative study. SAGE

Open, 3(April-June), 1-12. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/2158244013490708

Koufogiannakis, D. (2015). Determinants of evidence use in academic

librarian decision making. College &

Research Libraries, 76(1),

100-114. http://dx.doi.org/10.5860/crl.76.1.100

Leonard, A. (1999). Viable system model: Consideration of knowledge

management. Journal of Knowledge

Management Practice. Retrieved from http://www.tlainc.com/jkmp.htm

Lippincott, J. (2014). Designing

library spaces. Designing Libraries for the 21st Century III, University of

Calgary, Alberta, Canada.

Lloyd, A. (2013). Building information resilient workers: The critical

ground of workplace information literacy. What have we learnt? In S.

Kurbanoglu, E. Grassian, D. Mizrachi, R. Catts, & S. Spiranec (Eds.), Communications in computer and information

science series: Vol. 397. Worldwide

commonalities and challenges in information literacy research and practices:

European conference on information literacy. Revised selected papers. (pp.

219–228). Heidelberg, NY: Springer.

Materska, K. (2013). Is information literacy enough for a knowledge

worker? In S. Kurbanoglu, E. Grassian, D. Mizrachi, R. Catts, & S. Spiranec

(Eds.), Communications in computer and

information science series: Vol. 397. Worldwide

commonalities and challenges in information literacy research and practices:

European conference on information literacy. Revised selected papers. (pp.

229–235). Heidelberg, NY: Springer.

Mirijamdotter, A. (2010). Toward collaborative evidence based

information practices: Organisation and leadership essentials. Evidence Based Library and Information

Practice, 5(1), 17-25. Retrieved

from http://ejournals.library.ualberta.ca/index.php/EBLIP

Mirijamdotter, A., & Somerville, M. M. (2009). Collaborative design: An SSM-enabled organizational learning approach. International Journal of Information

Technologies and Systems Approach, 2(1),

48-69.

Nonaka, I. (1994). A dynamic theory of organizational knowledge

creation. Organization Science, 5(1), 14-37.

Nonaka, I. (2007). The knowledge-creating company. Harvard Business Review, 85,

162-171.

Nonaka, I., Konno, N., & Toyama, R. (2000). SECI, Ba and Leadership: a unified model of dynamic knowledge creation. Long Range Planning, 33, 5-34.

Nonaka, I., & Takeuchi, H. (1995). The knowledge-creating company: How Japanese companies create the

dynamics of innovation. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Nonaka, I., & Toyama, R. (2007). Why do firms differ? The theory of

the knowledge-creating firm. In K. Ichijo & I. Nonaka (Eds.), Knowledge creation and management: New

challenges for managers. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press.

Pan, D., & Howard, Z. (2009). Reorganizing a technical services division

using collaborative evidence-based information practice at Auraria Library. Evidence Based Library and Information

Practice, 4(4), 88-94. Retrieved

from http://ejournals.library.ualberta.ca/index.php/EBLIP

Pan, D., & Howard, Z. (2010). Distributing leadership and

cultivating dialogue with collaborative EBIP. Library Management, 31(7),

494-504.

Schön, D. (1983). The reflective

practitioner—How professionals think in action. New York, NY: Basic Books.

Senge, P. (1994). The fifth

discipline fieldbook: Strategies and tools for building a learning organization.

New York, NY: Doubleday/Currency.

Somerville, M. M. (2009). Working

together: Collaborative information practices for organizational learning. Chicago, IL: Association of College &

Research Libraries/American Library Association.

Somerville, M. M. (2013). Digital Age discoverability: A collaborative

organizational approach. Serials Review,

39(4), 234-239.

Somerville, M. M. (2015). Informed

Systems: Organizational design for learning in action. Oxford, England:

Chandos Publishing.

Somerville, M. M., & Conrad, L. Y. (2014). Collaborative improvements in the discoverability of scholarly content:

Accomplishments, aspirations, and opportunities. A SAGE White Paper. Los

Angeles, CA: SAGE Publications Ltd. Retrieved from http://www.sagepub.com/repository/binaries/pdf/improvementsindiscoverability.pdf

Somerville, M. M., & Conrad, L. Y. (2013). Discoverability challenges and collaboration opportunities within the

scholarly communications ecosystem: A SAGE white paper update. Collaborative Librarianship, 5(1), 29–41. Retrieved from http://www.collaborativelibrarianship.org/index.php/jocl

Somerville, M. M., & Farner, M. (2012). Appreciative inquiry: A

transformative approach for initiating shared leadership and organizational

learning. Revista de Cercetare si

Interventie Sociala [Review of Research and Social Intervention], 38(September), 7-24. Retrieved from http://www.rcis.ro/

Somerville, M. M., & Howard, Z. (2010). Information in context: Co-designing

workplace structures and systems for organizational learning. Information Research, 15(4). Retrieved from http://www.informationr.net/ir/

Somerville, M. M., Howard, Z., & Mirijamdotter, A. (2009). Workplace

information literacy: Cultivation strategies for working smarter in 21st

Century libraries. In D. M. Mueller (Ed.), Pushing

the Edge: Explore, Engage, Extend - Proceedings of the 14th

Association of College & Research Libraries National Conference,

Seattle, Washington (pp. 119-126). Chicago: Association of College &

Research Libraries.

Somerville, M. M., & Mirijamdotter, A. (2014). Information

experiences in the workplace: Foundations for an Informed Systems Approach. In

C. Bruce, H. Partridge, H. Hughes, K. Davis, & I. Stoodley (Eds.), Information Experience: Approaches to Theory

and Practice (pp. 203-220).

(Library and Information Science, Vol. 9) Bingley, England: Emerald.

Somerville, M. M., Mirijamdotter, A., Bruce, C. S., & Farner, M.

(2014). Informed Systems approach: New directions for organizational learning.

In M. Jaabæk & H. Gjengstø (Eds.), International

Conference on Organizational Learning, Knowledge, and Capabilities (OLKC 2014:

Circuits of knowledge). Oslo, Norway: BI Norwegian Business School.

Retrieved from http://www.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:714317/FULLTEXT02.pdf

Somerville, M. M., Rogers, E., Mirijamdotter, A., & Partridge, H. (2007).

Collaborative evidence-based information practice: The Cal Poly digital

learning initiative. In E. Connor (Ed.), Evidence-Based

Librarianship: Case Studies and

Active Learning Exercises (pp. 141-161). Oxford, England: Chandos

Publishing.

Somerville, M. M., Schader, B., & Huston, M. E. (2005). Rethinking

what we do and how we do it: Systems thinking strategies for library

leadership. Australian Academic and

Research Libraries, 36(4),

214–227.

Somerville, M. M., Schader, B. J., & Sack, J. R. (2012). Improving

the discoverability of scholarly content in the Twenty-First Century:

Collaboration opportunities for librarians, publishers, and vendors. A SAGE White Paper. Los Angeles, CA:

SAGE Publications Ltd. Retrieved from http://www.sagepub.com/repository/binaries/librarian/DiscoverabilityWhitePaper/

Townsend, A. (2014). Collaborative action research. In D. Coghlan &

Mary Brydon-Miller (Eds.), The SAGE encyclopedia

of action research (Vol. 1, pp. 116-119). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE

Publications Ltd.

Von Krogh, G., Ichijo, K., & Nonaka, I. (2000). Enabling knowledge creation: How to unlock the mystery of tacit

knowledge and release the power of innovation. London: Oxford University

Press.

Wawrzaszek,

S.V., & Wedaman, D.G. (2008). The academic library in a 2.0 world. Research Bulletin, issue 19, Boulder,

CO: EDUCAUSE Center for Applied Research.

![]() 2015 Somerville and Chatzipanagiotou. This is an Open Access article

distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

2015 Somerville and Chatzipanagiotou. This is an Open Access article

distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.