Conference Paper

Our Future, Our Skills:

Using Evidence to Drive Practice in Public Libraries

Gillian Hallam

Adjunct Professor, LIS

Discipline

Science and Engineering

Faculty

Queensland University of

Technology

Brisbane, Queensland,

Australia

Email: g.hallam@qut.edu.au

Robyn Ellard

Senior Program Manager,

Public Libraries

State Library Victoria

Melbourne, Victoria,

Australia

Email: rellard@slv.vic.gov.au

Received: 11 Aug. 2015 Accepted:

19 Oct. 2015

2015 Hallam and Ellard. This is an Open

Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

2015 Hallam and Ellard. This is an Open

Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

Abstract

Objective – The public library sector’s future prosperity is contingent upon a

well-trained, experienced, and valued workforce. In a collaborative initiative,

State Library Victoria (SLV) and the Public Libraries Victoria Network (PLVN)

commissioned an in-depth research study to examine the skills requirements of

staff across the State. The Our Future,

Our Skills project sought to identify the range of skills used by public

library staff today, to anticipate the range of skills that would be needed in

five years’ time, and to present a skills gap analysis to inform future

training and development strategies.

Methods – The project encompassed qualitative and quantitative research

activities: literature review and environmental scan, stakeholder interviews,

focus groups and a workforce skills audit. The research populations were staff

(Individual survey) and managers (Management survey) employed in 47 library

services, including metropolitan, outer metropolitan and regional library

services in Victoria.

Results – The high response rate (45%) reflected the relevance of the study, with 1,334

individual and 77 management respondents. The data captured their views related

to the value of their skillsets, both now and in five years’ time, and the

perceived levels of confidence using their skills. The sector now has a bank of

baseline evidence which has contributed to a meaningful analysis of the

anticipated skills gaps.

Conclusions – This paper focuses on the critical importance of implementing

evidence-based practice in public libraries. In an interactive workshop,

managers determined the skills priorities at both the local and sectoral levels

to inform staff development programs and recruitment activities. A

collaborative SLV/PLVN project workgroup will implement the report’s

recommendations with a state-wide workforce development plan rolled out during

2015-17. This plan will include a training matrix designed to bridge the skills

gap, with a focus on evaluation strategies to monitor progress towards

objectives. The paper provides insights into the different ways in which the

project workgroup is using research evidence to drive practice.

The world of public libraries is highly dynamic, with

staff being challenged to provide customers with a broad and diverse array of

services and programs in an environment characterised by tight public sector

budgets, ever-evolving technologies, a changing customer base and an ageing

workforce. In Australia, the State Library Victoria (SLV) has collaborated with

Public Libraries Victoria Network (PLVN), the peak body for Victoria’s 47

public library services, to address the challenges. Over the past decade a

number of initiatives have been undertaken to envision the public library

service of the future: Libraries Building Communities (State

Library Victoria (SLV), 2005); Workforce

Sustainability and Leadership (van Wanrooy, 2006; Considine, Jakubauskas & Oliver, 2008); Connecting with the Community (SLV, 2008); Tomorrow’s Library (Ministerial Advisory Committee (MAC), 2012);

and Victorian Public Libraries 2030

(also referred to as VPL 2030) (SLV,

2013a).

Specifically, the VPL

2030 study (SLV, 2013a) sought to establish a strategic vision for public

library services in Victoria. Following extensive consultation and a series of

workshops to explore community attitudes and needs, two scenarios for the

future were developed: the Community Library and the Creative Library. The

final report introduced a strategic framework which serves as a planning tool

to ensure the sector’s ability to meet the community’s expectations for the two

scenarios. It was emphasised that “a workforce of well-trained, experienced and

valued public library staff will be at the heart of our success” (SLV, 2013a,

p.1).

This statement provided the impetus for a further

state-wide study into the knowledge, skills and attributes which staff would

need to deliver future-focused library services and programs in the Community

Library and the Creative Library. The research activities in the Victorian Public Libraries: Our Future, Our

Skills project (SLV, 2014) focused on the workforce planning issues which

would underpin the successful achievement of the VPL 2030 goals.

Objectives

The Our Future,

Our Skills project sought to identify the range of skills currently used by

public library staff in their work, to anticipate the skills which would be

needed in five years’ time, and to present a skills gap analysis to inform

future training and development strategies. The overarching objectives of the Our Future, Our Skills project were to

develop a framework to articulate the core competencies required by the public

library workforce for the 21st century, to conduct a skills audit of Victorian

public library staff in order to collect data about the current skills and to

anticipate future requirements, and to deliver a report which analysed the

audit findings and made recommendations on training needs and strategies to

support the future delivery of public library programs and services in

Victoria.

Based on the skills presented in the framework, three

key questions were posed:

- How important is each skill to your current role?

- How important do you think each skill will be to the same role in

five years’ time?

- How confident do you feel in your ability to apply this skill in

the work that you do?

Managers of library services were asked to consider

the skills within the context of the library service:

- How important is each skill to the library service at the current

time?

- How important do you think each skill will be to the library

service in five years’ time?

The rich research data collected in the project will

enable future recruitment and staff development practice to be guided by meaningful

evidence. One of the biggest challenges faced by practitioners, however, is to

understand how to translate this evidence into practice.

Methodologies

The Our Future,

Our Skills project involved a number of qualitative and quantitative

research activities, including stakeholder interviews, a literature review and

environmental scan, the development of a skills framework to guide the design

of the survey instruments, a series of focus groups, and a skills audit of the

public library workforce in Victoria. In the earlier research project,

Considine, Jakubauskas and Oliver (2008) delineated three areas of workplace

skills (cited in Mounier, 2001):

- Cognitive skills – foundation or general skills obtained on the

basis of general citizenship (for example, literacy, numeracy, general

education competence)

- Technical skills – the skills associated with the purchase of

labour on the open market to perform particular tasks (for example, the

ability to operate machinery/technology, recognised trade or professional

skills)

- Behavioural skills – personal skills associated with labour’s

ability to deal with interpersonal relationships and to perform in the

context of authority relations on the job (for example, communication,

empathy, reliability, punctuality).

This overarching model was adopted for the literature

review and environmental scan (SLV, 2014, Appendix 2) with the structure of the

discussion built around these three skills areas. The changing world is driving

the need for an increased focus on contemporary cognitive skills, or Foundation

skills (Mounier, 2001) which are also described as 21st-century skills

(Ministerial Council on Education, Employment, Training and Youth Affairs,

2008; Partnership for 21st Century Skills, 2008; Institute of Museum

and Library Services, 2009). In order for citizens to successfully participate

in and contribute to a dynamic society, a new range of literacies is required

(UNESCO & IFLA, 2012; UNESCO, 2013; Institute of Museum and Library

Services, 2015a; Institute of Museum and Library Services, 2015b). The

combination of information literacy, media literacy, digital literacy and

technological literacy form a new metaliteracy (Mackey & Jacobson, 2011;

O’Connell, 2012; Jacobson & Mackey, 2013; Mackey & Jacobson, 2014). In

order for public libraries to remain relevant and meaningful in the future,

staff will need to demonstrate these 21st-century skills.

Technical skills – or Professional skills, as they are

termed in this study – may be more familiar to library workers. Traditionally,

education and training in the library and information science (LIS) field has

led to proficiency in the relevant Professional skills (Hirsch, 2012).

Professional associations and other bodies have developed their own LIS

frameworks to define the typical areas of professional practice (SLA, 2003;

ALA, 2009; Lifelong Learning UK, 2011; ALIA, 2012; LIANZA, 2013; CILIP, 2013;

Gutsche & Hough, 2014). The Australian Library and Information Association

(ALIA) core knowledge, skills and attributes policy document (ALIA, 2012)

guides the curricula of accredited library and information science (LIS)

education programs in Australia. Some critics argue, however, that LIS

education practice fails to meet the workforce requirements of the contemporary

public library sector (Partridge et al., 2011; Pateman & Willimen, 2013;

Bertot, Sarin & Percell, 2015).

Information and communications technology (ICT)

skills, especially the competencies required for the application of Web 2.0

technologies in libraries to facilitate participation, interaction and

co-creation of content are becoming increasingly important (King, 2007; Cullen,

2008; Harvey, 2009; Peltier-Davis, 2009; Partridge, Menzies, Lee & Munro,

2010). Mobile literacy is required by library staff in order to broaden access

to library resources and services and to link emerging technologies with new

opportunities to engage library users (Murphy, 2011; Saravani & Haddow,

2011).

The final skills area, Behavioural skills, has been

widely discussed in the professional literature (Partridge & Hallam, 2004;

Chan, 2005; Precision Consulting, 2006; Barrie, Hughes & Smith, 2009;

Oliver, 2011; ALIA, 2012). It is argued that the profession requires a richness

and diversity of Behavioural skills, with many employers stating that they wish

to appoint staff who have the ‘soft skills’, i.e. the personal and

interpersonal skills, that are pertinent both to the LIS profession and to the

wider employment environment (Kennan, Cole, Willard, Wilson & Marion, 2006;

Ralph & Sibthorpe, 2010; Reeves & Hahn, 2010; Howard, 2010; Partridge,

Menzies, Lee & Munro, 2010; Partridge et al., 2011; Haddow, 2012). Communication skills (Wilson & Birdi,

2008; Working Together Project, 2008; Abram, 2009; Saunders & Jordan;

2013), teamwork and collaboration skills (Bagshaw, 2013), adaptability, and

flexibility (Chawner & Oliver, 2013) are viewed as particularly important.

After the draft skills framework was reviewed by the

project reference group, it was examined and discussed by library staff in a series

of 15 focus groups held across Victoria. The focus group activities involved a

total of 133 participants, representing all levels of the workforce in small,

medium, and large library services and corporations, as well as library

educators from the higher education and the vocational education and training

(VET) sectors. The framework was subsequently affirmed by the project reference

group as the foundation for the Our

Future, Our Skills survey activities. The final version of the framework

includes 10 Foundation skills, 30 Professional skills and 19 Behavioural skills

(SLV, 2014, Appendix 3).

Research subjects for the study were all staff and

managers employed in public libraries in Victoria. All 47 library services,

including metropolitan, outer metropolitan, and regional library services, were

invited to participate in the project.

The total number of potential respondents was 2,975.

Two survey instruments were developed for the skills

audit: the Individual survey (SLV, 2014, Appendix 6), which was completed by

individual staff in different library services, and the Management survey (SLV,

2014, Appendix 7), which was open to selected senior staff with managerial

responsibilities and an understanding of the strategic direction of their

library service.

The questions in the Individual survey focused on the

individual staff member’s own skill sets and confidence levels, while the

questions in the Management survey examined the relevance of various skills to

the library service as a whole. The Individual surveys were made available to

all staff employed in Victorian public libraries, as prospective respondents,

through an online platform. Given the length of the questionnaires, the survey

tool was designed to allow respondents to answer the questions progressively,

rather than all in one session.

The Individual survey comprised four sections:

- Demographics

- Foundation skills

- Professional skills

- Behavioural skills.

An explanation of the scope of each skill area was provided,

as well as descriptors which typically represent the area of practice. There

were two open-ended questions at the end of each section to offer respondents

the opportunity to provide an indication of where they might benefit from

support and training, and to comment further on the skills area. At the

conclusion of the survey, respondents were invited to indicate how they

believed their role might change over the coming five years, and to outline any

‘hidden talents’ they had that might be of value to the library service.

The Management survey was more condensed than the

Individual survey and asked only two questions for each of the skill areas: the

importance of the skill set to the library service today, and the anticipated

importance of that skill to the library service in five years’ time.

Descriptors were again provided for each skill. Library managers had the

opportunity, through open-ended questions, to give their views on why there

might, or might not, be any change over the coming five-year period. They could

also offer general comments about the three skills areas.

The draft survey instruments were made available for

pilot testing. This study was underpinned by the principles of research quality

to ensure that the overall study design and the research questions resulted in

reliable and valid research findings. The reliability of the research design

was considered in the development and testing of the survey instrument. The

vocabulary used throughout the survey was kept consistent and descriptors were

provided for each competency area to assist the respondent in relating the

skills to their work role. For the pilot, the online questionnaires were

reviewed by a small representative sample of library staff, drawn from

different employment band levels and working with different library services in

Victoria. Some of the pilot testers had participated in the focus groups, while

others had not. Some minor adjustments to the questionnaires were made in

response to feedback from the pilot group.

The survey was open from 13 November 2013 to 20

December 2013. To verify the integrity of respondents, library staff members

were required to register for the survey using their work email addresses and

were then sent a system-generated password that enabled them to access the

questionnaire. The research team worked closely with the project team to

respond to any technical issues encountered. The stability and technical

performance of the online platform were monitored closely throughout the survey

period. The systems developer was able to monitor the registrations received to

ensure there were no duplicate registrations. Incomplete surveys were excluded

from the analysis.

Respondents were advised that their involvement in the

survey was completely voluntary and that they could withdraw at any time

without penalty. The research data collected remained anonymous and

confidential; email addresses were replaced with sequential numbers to ensure

respondents’ complete anonymity in the data analysis. The margin of error for

the Individual survey was calculated to be 3.7%; it was higher for the

Management survey, given a smaller sample size, at 8.9%.

Results

The high response rate (45%) reflected the relevance

of the Our Future, Our Skills study,

with 1,334 valid responses to the Individual survey and 77 valid responses to

the Management survey. Responses to the Individual survey were received from 45

library services, with response rates ranging from 7% to 100%. Managers from 37

library services contributed to the research through the Management survey.

Single responses were received from 19 libraries, while the remaining 18

library services provided between two and six management responses.

The VPL 2030 report

invites those involved in the public library sector in Victoria to begin to

think strategically about ways in which “public library staff, programs and

facilities can be better equipped to adapt and innovate to meet changing

community needs towards 2030 and beyond” (SLV, 2013b, p.2). The data collected

in the individual and management surveys in the Our Future, Our Skills project represent a bank of baseline

evidence which can contribute to a deeper understanding of the opportunities

and challenges.

The picture of the current workforce presents

confident and competent staff who deliver the library services that have long

been valued by users. The respondents’ strengths tend to reflect the core

knowledge and skills presented in ALIA’s policy document (ALIA, 2012) which is

used to guide the professional and vocational education programs in Australia.

The VPL 2030 report stresses,

however, that the status quo cannot continue; changing community attitudes and

behaviours will have a significant impact on the role libraries play and on the

programs and services they deliver. Inevitably, the ability to successfully

enable the current public library model to move to an alternative paradigm that

is relevant to the evolving information and learning needs of different

communities will depend on the competence and confidence of those working in

the sector. Public libraries will face the critical challenge of transitioning

effectively and smoothly from a passive, product-based model to one which can

deliver dynamic, service-based experiences (SLV, 2013a, p.17). Public library staff

will need to become actively engaged with the evolving social trends of

creativity, collaboration, mental engagement, learning and community

connection.

One of the primary drivers for societal change will

inevitably be the continuing influence of technology, as acknowledged in the VPL 2030 report: “technological

advancements and improved access to technology continue to enable scientific

breakthroughs and new social behaviours to emerge” (SLV, 2013a, p.11). The

Creative Library scenario is underpinned by developments in information and

communications technologies (ICT), while the push towards globalisation, which

is directly linked to the adoption of new technologies, influences the

Community Library scenario. As the VPL

2030 report presents only limited commentary about the skills requirements

for these future public library scenarios, the research data has been examined

to consider how the findings relate to three strategic perspectives: the

technology environment, the Creative Library and the Community Library.

Skills for the technology environment

The data collected through the Our Future, Our Skills surveys and the focus group discussions

revealed that there was a very keen awareness amongst public library managers and

staff about the challenges of the fast changing technology environment. Without

a doubt, digital literacy represents a fundamental Foundation skill needed by

library staff. Staff in all roles and at all levels will increasingly need to

demonstrate high levels of digital literacy as they apply their information and

media skills in a dynamic online world. In the context of public libraries

today, digital literacy skills were ranked as the fourth most important

Foundation skill by library managers (69% ‘extremely important’). Literacy,

cultural literacy and local awareness skills were identified as the three

principal Foundation skills for contemporary library staff, with literacy

viewed as the paramount skill. It was overwhelmingly apparent, however, that in

five years’ time, digital literacy skills would be just as important as

traditional literacy skills, with 94% of managers rating this skillset as

‘extremely important’ and the remaining 6% stating it would be ‘important’. An

enormous increase in significance was also anticipated by individual library

staff, with those rating it as ‘extremely important’, jumping from 58% to 84%

in the five year timeframe. It was recognised that all library staff would

quickly need to become fluent in the area of digital literacy and that

operational ICT skills would become mainstream:

- ICT policy and planning

- Development and management of ICT systems in the library

- Integration of social media and mobile applications into library

operations

- Provision of ICT support to customers

- Management of digital resources

- Creation and maintenance of metadata schema.

Behavioural skills also came under scrutiny: the

dynamic and ever-evolving technology environment demands flexibility, with

staff encouraged to respond positively and confidently to constant change and

to willingly accept new work assignments and job responsibilities. Creative

thinking and problem solving were likely to become essential skills in a less

predictable world: public library staff would need to be able to seek out and

promote new ideas and to test novel approaches to resolving operational issues.

A commitment to lifelong learning would be an imperative, with staff prepared

to take responsibility for their ongoing learning and professional development

through avenues of both informal and formal learning.

While technological developments were clearly going to

make a significant impact on library operations in the coming years, one major

area of concern for public libraries was the staff members’ present levels of

confidence in utilising the various skillsets. The gap between managers’

expectations for the importance of the different skill areas and the number of

staff who stated that they felt ‘very confident’ (Likert scale 5) about

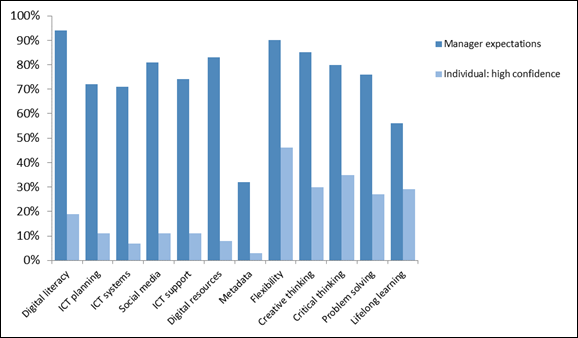

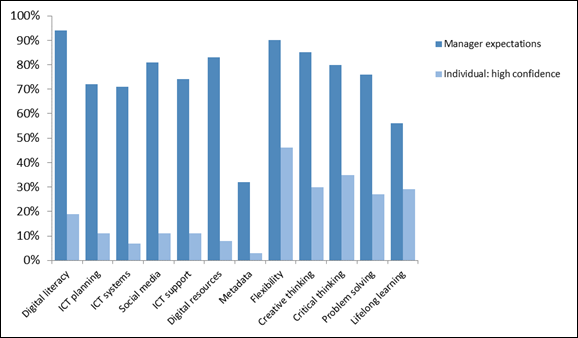

utilising the skill in their current role is depicted in Figure 1. Relatively

strong levels of confidence were recorded for the Behavioural skills, but in

the area of the Professional skills relating to ICT in libraries, the

confidence levels were extremely low.

Figure 1: Gap

analysis: skills required

in the technology environment.*

*Managers’ expectations (‘extremely important’) and

Individual confidence (‘very confident’).

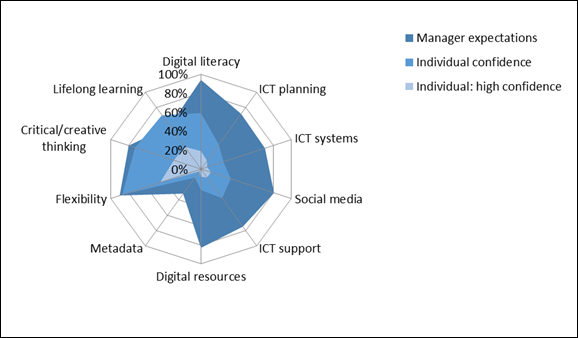

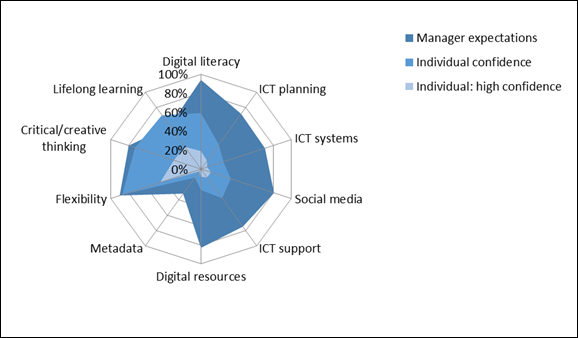

Figure 2: Gap

analysis: skills required in the technology environment.*

*Managers’ expectations (‘extremely important’) and

Individual confidence (‘very confident’)

Figure 2 presents the Foundation skills

and Professional skills data as a spidergram; the managers’ expectations for

future skills requirements for the library (dark blue) are contrasted with the

individuals’ current levels of confidence. The graph shows both medium and high

levels of confidence by presenting the aggregated responses for ‘confident’

(Likert scale 4) and ‘very confident’ (Likert scale 5) (mid blue), as well as

the specific data for ‘very confident’ (Likert scale 5) (light blue).

As the graph

illustrates, while the current skill level appears to be low – especially in

relation to the Professional skills – there is a small kernel of staff who have

the appropriate skill sets and a further group of staff who feel their skills

are developing well. Importantly, opportunities may exist within the workforce

to draw on the skills of these people to contribute to informal staff

development activities, e.g. through work shadowing and mentoring.

It is essential that public

library staff commit to the process of skills development to be able to perform

at a high level in this dynamic technology environment. As few areas of the

public library of the future were likely to remain untouched by ICT

developments, there was a clear sense that the entire workforce would need to

up-skill if staff were to operate productively in the world of electronic

information and to help members of the community develop their own digital

literacy skills. Training and development activities to address the current low

levels of digital literacy and ICT skills should be regarded as a high priority

for the Victorian public library sector.

Skills for the

Creative Library

The depiction of a

future Creative Library, as outlined in the VPL

2030 report, is heavily influenced by technology, particularly through the

application of participative and collaborative tools to create and share

digital resources in a range of media formats. The creative public library has

been described as an active learning centre; community arts studio; and

collaborative work space. As staff of the Creative Library become “facilitators

of creative development, expression and collaboration” (SLV, 2013a, p.21), they

will need the skills and abilities to run a broad selection of creative and

learning programs which contribute to building the inventive capacity of the

community. In this environment, public library staff will be required to use a

variety of skills to manage and coordinate both internal and external

resources:

- To facilitate

content sharing

- To connect people

- To teach new

skills

·

To nurture untapped talent

- To produce,

record and edit creative content

- To host business

collaboration

- To manage people

- To coordinate

multiple diverse activities within the library and across different

stakeholder groups.

The skills relevant to

the Creative Library can be mapped to all three fields of the skills framework:

digital literacy and cultural literacy as key Foundation skills; cultural programming,

creative making, and literacies and learning as Professional skills; creative

thinking, problem solving, customer engagement, building partnerships and

alliances, and lifelong learning as important Behavioural skills. At the same

time, a wider range of Professional skills should not be ignored, as staff in

the Creative Library will need to draw on their understanding of the ICT

environment and their skills in information seeking, eResource management,

information services, project management, marketing and promotion.

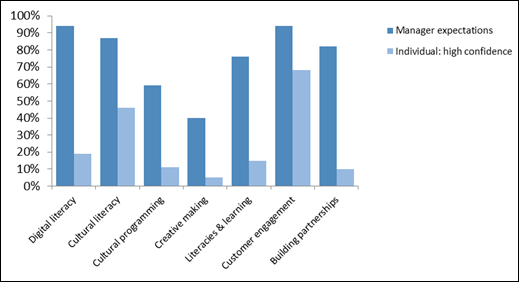

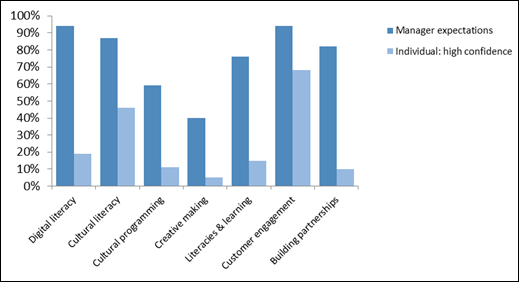

Figure 3 correlates

staff confidence levels with the managers’ expectations about the future

importance of the specific areas of competency required for the Creative

Library. High levels of confidence recorded for customer service and cultural

literacy contrasted strongly with low levels of confidence recorded for the

areas of literacies and learning, cultural programming, creative making and

building relationships and alliances.

Figure 3:

Gap analysis: skills required for the creative library scenario.*

*Managers’

expectations (‘extremely important’) and Individual confidence (‘very

confident’)

In Figure 4, the

spidergram presents the comparison between the managers’ expectations for

future skillsets and the individual respondents’ data: high levels of

confidence (Likert scale 5) and the combined levels of ‘confident’ (Likert

scale 4) and ‘very confident’ (Likert scale 5).

Figure 4: Gap analysis: skills required for the

creative library scenario.*

*Managers’

expectations (‘extremely important’) and Individual confidence (‘very

confident’)

The graphs highlight

the areas where skills development is essential if Victorian public libraries

are to achieve the aspiration of meeting the expectations of a creative

community.

Skills for the

Community Library

The second scenario

discussed in the VPL 2030 report was

the Community Library. In this scenario the library plays the role of “a learning village” (SLV, 2013a, p.25), with

the potential to play a central role as community learning centre; gathering

place; brain gymnasium; repository, documenter and disseminator of local

knowledge; and local business hub. The responsibilities of public library staff

in this environment are broad ranging: to develop community capacity by

connecting people who have either similar interests or complementary skills.

The effective management and coordination of internal and external resources

would again be integral to the success of the library.

The essential

competencies for staff of the Community Library can be drawn from all three

fields of the Our Future, Our Skills

framework. Significant Foundation skills would include local awareness to

comprehend the socio-demographic and cultural characteristics of the different

populations who use library services, as well as those of non-users. While the

staff who deliver programs and services in the Community Library would continue

to draw on some of their more traditional skillsets (e.g. information seeking,

resource management, people management, project management, and marketing and

promotion), the most critical Professional skills would relate to community

development. The field of community development encompasses community needs

analysis, for example, through socio-demographic analysis, community profiling

and community mapping; community engagement, especially in relation to issues

of social exclusion; and establishing productive relationships with other

community groups and volunteers. This last skillset is closely aligned with the

Behavioural skills relating to building partnerships and alliances across the

public and private sectors, which in turn would be augmented by skills in

political and business acumen in order to contextualise the environment in

which the library operates. Other Behavioural skills such as effective

communication, customer engagement and empathy would continue to be

important.

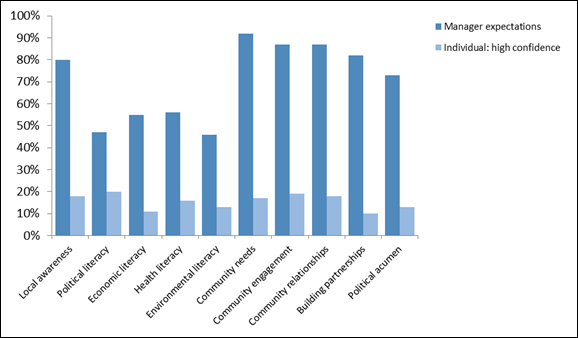

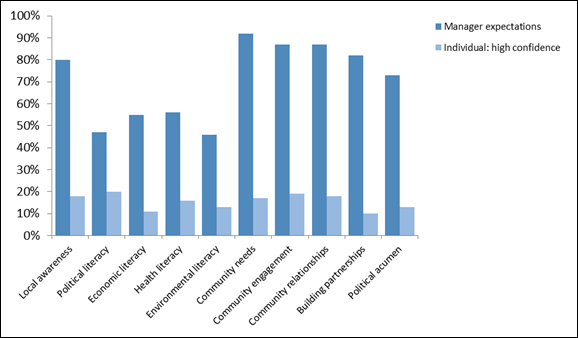

Figure 5: Gap analysis: skills required for the

community library scenario.*

*Managers’ expectations

(‘extremely important’) and Individual confidence (‘very confident’).

The Community Library

scenario would therefore require a mix of skills that are, arguably,

underdeveloped at the present time. Although staff confidence levels were

marginally stronger in this scenario, a degree of discord was still apparent

when they were compared with the value placed on the skillsets by library

managers, particularly in the context of community development skills. The gap

between managers’ views of the future of these skill areas and the confidence

felt by staff is presented graphically in Figure 5.

This data is further

amplified in Figure 6 to show the combined individual responses for ‘confident’

(Likert scale 4) and ‘very confident’ (Likert scale 5).

Figure 6: Gap analysis: skills required for the

community library scenario.*

*Managers’

expectations (‘extremely important’) and Individual confidence (‘very

confident’).

Strategies for the

future

Konrad (2010) stresses

that the development of staff competence is intrinsically linked to

organisational development, so library leaders face the challenge of ensuring

that their staff have the right skills to work in an organisation that

encourages and supports interdisciplinary teams and networks within and across

the cultural sector. Staff will also need to be able to respond and contribute

to an organisation that has the capacity to embrace the “processes of change and

development as a permanent condition for the sector” (Konrad, 2010). The future

scenarios of the Creative Library and the Community Library anticipate “a

flexible and inclusive organisational culture that attracts and retains people

with the right skills and attitude” (SLV, 2013a, p.31) in order to design and

deliver the programs and services that will place the public library service at

the centre of an active and engaged community. The “right skills and attitude”

encompass a range of the competency areas presented in the Our Future, Our Skills framework. Some of these skillsets may be

regarded as ‘traditional’ LIS skills while others can be described as ‘new’

skills.

The research findings

indicated that public library staff perform well in those areas where their

skills have long been tried and tested: they are “well-trained, experienced and

valued” (SLV, 2013a, p.1). However, some of the competency areas that are

directly relevant to the Creative Library and the Community Library can be

described as underdeveloped. While some of the skills are beginning to become

relevant to public library practice, staff levels of confidence are very low.

This is particularly the case with the skillsets relating to cultural

programming, creative making, literacies and learning, and community

development. The final report for the Our

Future, Our Skills project included a number of recommendations relating to

the development of a set of priorities to help position the Victorian public

library sector for the delivery of future-focused programs and services, to use

the skills framework as a multi-purpose workforce planning tool, and to develop

a productive staff training and development framework.

Translating evidence into practice

The aim of the Our Future, Our Skills research project

was to establish an evidence-based assessment of the training needs of

Victorian public library staff. A major issue was, once the research activities

had concluded and the research data had been analysed, how should the findings

and recommendations be used in practice? While many public library managers may

be becoming increasingly aware of the importance of evidence-based library and

information practice, they face significant difficulties when it comes to

translating evidence into practice.

The research data and

recommendations were acknowledged to be key ingredients for future planning

efforts. Nevertheless, during the initial review and discussion of the final

report by the workgroup which had been responsible for commissioning the project,

it became clear that many practitioners in the library and information sector

struggled with translating research evidence into everyday solutions. In order

to assist librarians in interpreting the data and the final recommendations, a

number of actions were implemented. In July 2014, Victorian library service

managers, CEOs and senior staff were invited to attend an interactive workshop

led by the researcher. The research process was described, the recommendations

were examined and the priorities for skills development and training programs

were discussed. Workshop participants identified the skills priorities at both

the local and sectoral levels to inform staff development programs and

recruitment activities.

The workshop provided

a good foundation for senior library managers to understand the importance of

the recommendations, the rigour of the research and the value of applying

evidence based practice in libraries. One of the recommendations in the final

report was the development of a workforce action plan for Victorian public

libraries: this became the collaborative workgroup’s first undertaking. It was

agreed that the action plan should align with the Victorian public library

sector’s strategic direction and agreed priorities, as outlined in the VPL 2030 document.

The project workgroup

undertook an analysis of the two reports, VPL

2030 and Our Future, Our Skills, to

establish the critical priorities for the training programs to be delivered

during the 2014-2017 timeframe. The workgroup identified the levels and

positions of staff that would benefit from specific training and development,

as well as the preferred methods of delivery for the training programs. Four

key themes were identified:

- Building partnerships and alliances

- Community development and engagement

- Digital literacy

4. Collection

development.

In developing the

workforce action plan, the project workgroup scrutinised each of the four key

themes to identify:

- Why the theme was critical to the work of public libraries

- What skills should be included under each theme

- What skills gaps currently existed

- What training and development response was required

- How to ensure that the response truly reflected the needs of the

public library workforce (e.g. improving access to training opportunities

for staff in regional libraries)

- Which library staff would benefit most from the different types of

training.

The collated

information was translated into a training matrix to drive workforce

development over the period 2015-2017. The value of the evidence collected

through the Our Future, Our Skills project

was acknowledged through a successful grant application to the R.E. Ross Trust,

a charitable trust in Victoria. One specific area of interest is to provide

funding for initiatives which offer “improved access to and achievement of

equity and excellence in public education, arts and culture”. The application

submitted by SLV recognised the innovative nature of the research work and

highlighted the importance of implementing the recommendations. The funding

will support the delivery of the training program in a range of formats across

the state to ensure an equitable spread of professional development

opportunities to ensure that public libraries and their staff are well equipped

to service the needs of all Victorian communities now and into the future.

In order to further

build on the evidence base, evaluation strategies have been developed to allow

the workgroup to monitor the progress made towards reducing the skills gaps. A

two-stage evaluation involves assessing the impact of each training course with

each participant at the end of the event to consider the effectiveness of the

learning activities, and again four weeks later via a survey designed to

explore the impact the training had on the attendees’ methods, attitude and

approach to their work. After the first training event, it was found that

levels of confidence had increased, with some respondents reporting significant

changes:

I have put in a

funding application for a LEGO Mindstorm program after hearing how successful

it was at Geelong Regional Library Service.

[I’ve] bought an iPad

for my own professional learning and development.

[There’s been] more of

a change in attitude underpinning my relationships with colleagues and community

groups.”

All the events have

had an impact on my thinking and will influence how I will structure my future

career - I am sure that it has already impacted on my practice.

Conclusions

Library managers face

immense challenges to fully comprehend the nature and value of the evidence

gathered through the Our Future, Our

Skills project and to develop effective and workable strategies for a

strong and successful public library sector. The library workforce will be

integral to the sector’s future success and it is essential that managers

develop a clear set of priorities to address skills needed in the future. Some

workplace tasks which are currently viewed as routine will inevitably be

subject to ongoing change: technological developments will streamline mundane

activities and some traditional library roles will become redundant. Together,

SLV and PLVN are well positioned to use the VPL

2030 strategic framework as the springboard to progressively introduce a

range of training programs which will enable staff to develop new resources and

services to meet the changing needs of the communities they serve.

In both the Creative

Library and Community Library scenarios, emphasis is placed on members of the community

striving to develop new knowledge and skills. Accordingly, in this dynamic

learning environment, it is essential that staff employed in public libraries

are also motivated to see themselves as learners. At the conclusion of the

study, managers of a number of individual library services requested the

analysis of the data directly relating to their staff, to be compared with the

aggregated state-wide data. Key areas of strength could be identified, as well

as those areas where the skill sets were particularly underdeveloped. The

differences between metropolitan and regional libraries highlighted the

opportunities to support knowledge exchange and skills development across the

state though staff exchanges, job swaps and peer mentoring programs. As it will

be important to monitor the impact of the workforce development plan, the

survey instrument can be used again to collect updated evidence in order to

measure the progress being made towards the upskilling of staff over time.

As libraries forge new

directions, alternative career pathways will emerge, with roles that require

people to draw on a different range of skills. The value of the research

activities undertaken in the public library sector in Victoria extends beyond

this immediate context, not only to public libraries in other jurisdictions

within Australia and overseas, but also to other sectors of library and

information practice. As a living document, the skills framework can be used as

multi-purpose workforce planning tool to raise awareness among library staff

about the importance and value of the range of skills which underpin high

quality practice, to support performance planning and review processes in

libraries, to review staffing structures in order to align skills requirements

with library programs and services, to support the recruitment of high calibre

library staff, and to advocate on library workforce issues with key

stakeholders. The research should also stimulate debate between practitioners,

educators and professional associations about the future direction of LIS

education with the goal of ensuring a strong future for the sector.

References

Abram, S. (2009). The new librarian: Three

questions. Information Outlook, 13(6),

37-38.

American Library Association (ALA) (2009). Core competences of librarianship.

Retrieved July 1, 2015 from http://www.ala.org/educationcareers/careers/corecomp/corecompetences

Australian Library and Information Association

(ALIA) (2014). The library and

information sector: Core knowledge, skills and attributes. Retrieved on

July 1, 2015 from http://www.alia.org.au/about-alia/policies-standards-and-guidelines/library-and-information-sector-core-knowledge-skills-and-attributes

Bagshaw, M. (2013, March 1). Is there no ‘I’

in ‘teamwork’? Library Journal: Backtalk Retrieved

November 22, 2015 from http://lj.libraryjournal.com/2013/03/opinion/backtalk/is-there-no-i-in-teamwork-backtalk/

Barrie, S., Hughes, C., & Smith, C.

(2009). The national graduate attributes

project: Integration and assessment of graduate attributes in curriculum.

Sydney: Australian Learning and Teaching Council. Retrieved July 1, 2015 from http://www.itl.usyd.edu.au/projects/nationalgap/resources/gappdfs/national%20graduate%20attributes%20project%20final%20report%202009.pdf

Bertot, J.C., Sarin, L.C., & Percell, J.

(2015). Re-envisioning the MLS: Findings,

issues, and considerations. College Park, MD: University of Maryland

College Park, College of Information Studies. Retrieved August 15, 2015 from http://mls.umd.edu/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/ReEnvisioningFinalReport.pdf

Chan, D. (2005, Jun.). Core competencies for

public librarians in a networked world. Data, information, and knowledge in a

networked world. Proceedings of the Annual Conference of the Canadian

Association for Information Science. London, Ontario. Retrieved July 1, 2015 from http://www.cais-acsi.ca/ojs/index.php/cais/article/view/167/657

Chartered Institute of Library and Information

Professionals (CILIP) (2013). Professional

knowledge and skills base. Retrieved July 1, 2015 from http://cilip.org.uk/cilip/jobs-and-careers/professional-knowledge-and-skills-base

Chawner, B., & Oliver, G. (2013). A survey

of New Zealand academic reference librarians: Current and future skills and

competencies. Australian Academic&

Research Libraries, 44(1), 29-39.

Considine, G., Jakubauskas, M., & Oliver,

D. (2008). Workforce sustainability and

leadership: Survey, analysis and planning for Victorian public libraries.

Sydney: University of Sydney, Workplace Research Centre. Retrieved on July 1,

2015 from http://www.libraries.vic.gov.au/downloads/Workforce_Survey_Analysis_and_Planning_Project/finalworkforcereport.pdf

Cullen, J. (2008). Catalyzing innovation and

knowledge sharing: Librarian 2.0. Business

Information Review, 25(4), 253-258.

Gutsche, B., & Hough, B. (2014). Competency index for the library field. Dublin,

OH: WebJunction. Retrieved July 1, 2015 from http://www.webjunction.org/content/dam/WebJunction/Documents/webJunction/2015-03/Competency%20Index%20for%20the%20Library%20Field%20(2014).pdf

Haddow, G.

(2012). Knowledge, skills and attributes for academic reference librarians. Australian Academic and Research Libraries,

43(3), 231-248.

Harvey, M. (2009). What does it mean to be a

science librarian 2.0? Issues in Science

and Technology Librarianship, 58, 2.

Retrieved July 1, 2015 from http://www.istl.org/09-summer/article2.html

Hirsch, S. (2012). Preparing future

professionals through broad competency planning. Information Outlook, 16(1), 9-11.

Howard, K. (2010). Programming not required:

Skills and knowledge for the digital library environment. Australian Academic & Research Libraries, 41(4), 260-275.

Institute of Museum and Library Services

(IMLS) (2009). Museums, libraries and 21st

century skills. Washington, DC: IMLS. Retrieved 1 July, 2015, from http://www.imls.gov/assets/1/AssetManager/21stCenturySkills.pdf

Institute of Museum and Library Services

(IMLS) (2015a). Museums, libraries and 21st

century skills. Retrieved November 22, 2015 from https://www.imls.gov/issues/national-initiatives/museums-libraries-and-21st-century-skills

Institute of Museum and Library Services

(IMLS) (2015b). Museums, libraries and 21st

century skills: Definitions. Washington, DC: IMLS. Retrieved November 22,

2015, from https://www.imls.gov/impact-imls/national-initiatives/museums-libraries-and-21st-century-skills/museums-libraries-and-21st-century-skills-definitions

Jacobson, T.E., & Mackey, T.P. (2013,

Apr.). What’s in a name?: Information

literacy, metaliteracy or transliteracy. Presentation at the meeting of

ACRL: Imagine, Innovate, Inspire. Association of College & Research

Libraries Conference 2013, Indianapolis IN. Retrieved on 1 July, 2015 from http://www.slideshare.net/tmackey/acrl-2013

Kennan, M.A., Cole, F., Willard, P., Wilson,

C., & Marion, L. (2006). Changing workforce demands: What job ads tell us. Aslib Proceedings, 58(3), 179-196.

King, D.L. (2007, July 11). Basic competencies

of a 2.0 librarian, take 2 [Web log post]. Retrieved November 22, 2015 from http://www.davidleeking.com/2007/07/05/basic-competencies-of-a-20-librarian/

Konrad, I. (2010). Future competence needs in

public libraries. Scandinavian Public

Library Quarterly, 43(4), 8-9. Retrieved on July 1, 2015 from http://slq.nu/?article=denmark-future-competence-needs-in-public-libraries

Library and Information Association of New

Zealand (LIANZA). Taskforce on Professional Registration (2013). LIANZA Professional Registration Board

professional practice domains and bodies of knowledge. December 2013. Retrieved

November 22, 2015 from http://www.lianza.org.nz/sites/default/files/Updated%20LIANZA%20Professional%20Practice%20Domains%20and%20Bodies%20of%20Knowledge%20-%20V3.pdf

Lifelong Learning UK (LLUK) (2011). National Occupational Standards: Libraries,

archives, records and information management services. Retrieved July 1,

2015 from http://www.slainte.org.uk/news/archive/1103/LARIMS%20NOS%20Final%20Approved%20Feb11.pdf

Mackey, T.P., & Jacobson, T. E. (2011).

Reframing information literacy as a metaliteracy. College & Research Libraries, 72(1), 62-78.

Mackey, T.P., & Jacobson, T.E. (2014). Metaliteracy: Reinventing information

literacy to empower learners. Chicago, IL: ALA Neal-Schuman.

Ministerial Advisory Council on Public Libraries

(MAC) (2012). Review of Victorian public

libraries: Stage 1 report. Retrieved on November 22, 2015 from http://www.dtpli.vic.gov.au/local-government/public-libraries/tomorrows-library-stage-1-and-2

Ministerial Council on

Education, Employment, Training and Youth Affairs (MCEETYA) (2008). Melbourne declaration on educational goals

for young Australians. Retrieved on July 1, 2015 from http://www.curriculum.edu.au/verve/_resources/National_Declaration_on_the_Educational_Goals_for_Young_Australians.pdf

Mournier, A. (2001). The three

logics of skill in French literature. Australian Centre for Industrial

Relations Research and Training (ACIRRT) Working Paper for the Board Research

Project: The Changing Nature of Work -

Vocational education and training to enable individuals and communities to meet

the challenges of the changing nature of work. Sydney: University of

Sydney, ACIRRT. Retrieved on November

22, 2015 from http://ses.library.usyd.edu.au/bitstream/2123/13397/1/WP66.pdf

Murphy, J. (2011, April 1). Social networking

literacy for librarians. ACRL paper update [Web log post]. Retrieved July 1,

2015 from http://joemurphylibraryfuture.com/social-networking-literacy-for-librarians-acrl-paper-update/

O’Connell, J. (2012). Learning without frontiers: School libraries and

meta-literacy in action. Access, 26(1),

4-7.

Oliver, B. (2011). Good practice report: Assuring graduate outcomes. Sydney:

Australian Learning and Teaching Council. Retrieved July 1, 2015 from http://www.olt.gov.au/resource-assuring-graduate-outcomes-curtin-2011

Partnership for 21st Century

Learning (P21) (2008). Framework for 21st

century learning. Retrieved July 1, 2015 from http://www.p21.org/our-work/p21-framework

Partridge, H., Menzies, V., Lee, J., &

Munro, C. (2010). The contemporary librarian: Skills, knowledge and attributes

required in a world of emerging technologies. Library & Information Science Research, 32(4), 265-271.

Partridge, H. L., Hanisch, J., Hughes, H. E.,

Henninger, M., Carroll, M., Combes, B., Genoni, P., Reynolds, S., Tanner, K.,

Burford, S., Ellis, L., Hider, P., & Yates, C. (2011). Re-conceptualising and re-positioning Australian library and

information science education for the 21st century: Final report.

Retrieved November 22, 2015 from http://eprints.qut.edu.au/46915/

Partridge, H., & Hallam, G. (2004, Sept.).

The double helix: A personal account of the discovery of the structure of the

information professional’s DNA. In Challenging

ideas. ALIA 2004 Biennial Conference. Gold Coast, Australia. Retrieved July

1, 2015 from http://eprints.qut.edu.au/1215/

Pateman, J., & Willimen, K. (2013). Developing community-led public libraries:

Evidence from the UK and Canada. Farnham, Surrey, UK: Ashgate Publishing.

Peltier-Davis, C. (2009). Web 2.0, library 2.0,

library user 2.0, librarian 2.0: Innovative services for sustainable libraries. Computers in Libraries, 29(10), 16-21.

Precision Consultancy (2006). Employability skills: From framework to

practice. An introductory guide for trainers and assessors. Canberra:

Department of Education, Science and Training. Retrieved July 1, 2015 from http://www.velgtraining.com/library/files/Employability%20Skills%20From%20Framework%20to%20Practice%20%20An%20introductory%20Guide%20for%20Trainers%20and%20Assessors.pdf

Ralph, G., & Sibthorpe, J. (2010).

Learning from job advertisements for New Zealand special librarians. New Zealand Library & Information

Management Journal, 51(4), 216-235.

Reeves, R. K., & Hahn, T. B. (2010). Job

advertisements for recent graduates: Advising, curriculum, and job-seeking

implications. Journal of Education for

Library & Information Science, 51(2), 103-119.

Saravani, S-J., & Haddow, G. (2011). The

mobile library and staff preparedness: Exploring staff competencies using the

unified theory of acceptance and use of technology model. Australian Academic & Research Libraries, 42(3), 179-190.

Saunders, L., & Jordan, M. (2013).

Significantly different?: Reference service competencies in public and academic

libraries. Reference & User Services

Quarterly, 52(3), 216-223.

SLA (2003). Competencies for information professionals in the 21st

century. Revised edition. Retrieved July 1, 2015 from http://www.sla.org/about-sla/competencies/

State Library of Victoria (SLV) (2005). Libraries building communities: The vital

contribution of Victorian public libraries – a research report for the Library

Board of Victoria and the Victorian Public Library Network. Melbourne:

State Library of Victoria. Retrieved on July 1, 2015 from http://www2.slv.vic.gov.au/about/information/publications/policies_reports/plu_lbc.html

State Library of Victoria (SLV) (2008). Connecting with the community.

Melbourne: State Library of Victoria.

Retrieved on July 1, 2015 from http://www2.slv.vic.gov.au/pdfs/aboutus/publications/lbcreportcommunity.pdf

State Library of Victoria (SLV) (2013a). Victorian public libraries 2030: Strategic

framework. Melbourne: State Library of Victoria. Retrieved on July 1, 2015

from www.plvn.net.au/sites/default/files/20130527%20FINAL%20VPL2030%20Full%20Report_web.pdf

State Library of Victoria (SLV) (2013b). Victorian public libraries 2030: Strategic framework. Summary report. Melbourne: State Library

of Victoria. Retrieved on July 1, 2015 from http://plvn.net.au/sites/default/files/20130528%20FINAL%20VPL2030%20Summary%20Report_web.pdf

State Library of Victoria (2014). Victorian public libraries: Our future, our

skills: Research report. Melbourne: State Library of Victoria. Retrieved on

July 1, 2015 from http://www.plvn.net.au/sites/default/files/Skills%20Audit%20Report%20FINAL.pdf

United Nations Educational, Scientific and

Cultural Organization (UNESCO) & International Federation of Library

Associations (IFLA) (2012). The Moscow

declaration on media and information literacy. Retrieved July 1, 2015 from http://www.ifla.org/publications/moscow-declaration-on-media-and-information-literacy

United Nations Educational, Scientific and

Cultural Organization (UNESCO) (2013). Media

and information literacy for knowledge societies. Moscow: UNESCO. Retrieved

July 1, 2015 from http://www.ifapcom.ru/files/News/Images/2013/mil_eng_web.pdf

University of Sydney, Workplace Research

Centre. Retrieved July 1, 2015 from http://www.libraries.vic.gov.au/downloads/Public_Libraries_Unit/final_workforce_scoping_report_jul_06.pdf

van Wanrooy, B. (2006). Workforce sustainability and leadership: Scoping research. Sydney:

University of Sydney, Workplace Research Centre. Retrieved July 1, 2015 from http://www.libraries.vic.gov.au/downloads/Public_Libraries_Unit/final_workforce_scoping_report_jul_06.pdf

Wilson, K. & Birdi, B. (2008). The right man for the job?: The role of

empathy in community librarianship. Sheffield: University of Sheffield.

Retrieved July 1, 2015 from http://www.shef.ac.uk/polopoly_fs/1.128131!/file/AHRC-2006-8-final-report-04.08.pdf

Working Together Project (2008). Community-led libraries toolkit.

Retrieved July 1, 2015 from http://www.librariesincommunities.ca/resources/Community-Led_Libraries_Toolkit.pdf

![]() 2015 Hallam and Ellard. This is an Open

Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

2015 Hallam and Ellard. This is an Open

Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.