Introduction

Legal Aid Queensland (LAQ) provides legal help to

financially disadvantaged Queenslanders in criminal, family and civil law

matters. LAQ Library Services provides a full range of services to

approximately 250 lawyers as well as social workers, executive management

staff, policy staff and support staff across 14 locations. The library has the

equivalent of 3.3 full time staff. Our two librarians and two library

technicians all provide training services.

Training has been a part of the library’s role for the

last 30 years. A formal library training plan was first produced in 2008; a

major revision was undertaken in 2014. The plan now consists of:

1. the strategic plan which outlines training policy and

the theoretical underpinnings and context of the library’s training program;

2. the operational plan which outlines seven training

components;

3. the training needs analysis methodology; and

4. the annual training schedule.

The seven current training components include:

·

Induction

training – new legal and support staff receive an introduction to library

services from a library staff member as part of their induction process. The

session with a library staff member is tailored to the specific role of the

inductee within the organization and is delivered face to face or via screen

casting depending on the staff member’s location.

·

Individual

training – provided to all library clients at point of need. It is the

preferred method of library training. It includes face to face and remote

training via screen casting, and typically involves working through a specific

research problem with the client. It also includes several self-directed

learning initiatives including factsheets and help guides, and video on demand

continuing professional development (CPD).

·

Group training –

formal training events are offered by the library including regular small group

workshops, and occasional lecture style CPD presentations.

·

Regional office

training – library staff visit regional offices once each year to provide face

to face training to regional library clients, including formal group training

and individual training as required.

·

Library

awareness – raising awareness within the organization of the services and

resources offered by the library. We achieve this through information sessions,

blog items, web news updates, and emails about new resources to individual

clients and teams. Daily emails alerting staff to new judgments and weekly

legislation updates help lawyers keep up to date with developments in the law.

·

External

training – raising awareness of the LAQ library and the broader organization

within the legal library sector through staff presenting at conferences,

writing articles and papers and active participation in professional

associations.

·

Library staff

professional development – increasing library staff capacity to provide quality

services to our client through actively engaging with our own professional

development activities, including self-directed learning, attending in-house

training sessions, and external conferences and other professional development

opportunities.

The training needs analysis process was designed to

provide an evidence basis for developing future training activities and

assessing the effectiveness of the current training program.

As this was the first structured TNA undertaken, it

further asked whether evidence from library database usage logs,

publisher-provided usage statistics, research request data analysis, and

qualitative evidence from client stakeholder interactions could reliably be

used to improve the relevance and effectiveness of our training program.

For the purposes of this first TNA we chose to analyse

data from the 2014 calendar year only. The decision to limit our analysis to

this period was taken because:

·

it was the most

recent complete set of data we had for all the components of the analysis;

·

we determined

that it provided a dataset large enough to give meaningful results; and

·

it was a

manageable dataset given the time constraints on completing the analysis.

Literature Review

McGehee and Thayer (1961) first observed that training

should be underpinned by systematic research into training needs. They

introduced a model framework of organizational, operational and individual

analyses that needed to be assessed as a whole to inform effective training.

Examples of librarians using training needs analyses can be found in the

literature though most provide little insight to their methodology.

Additionally, most take a less holistic approach, often relying solely on written

self-assessment instruments. For example, Johnson refers to a database training

needs [self] analysis form (2005), and surveys were used in a study reported by

Bresnahan and Johnson (2013) and Turner, Rosen and Wilkie (2003). Interviews

with management can complement survey data (Oldroyd, 1995). Allred (1995) questioned the validity of

self-assessment as a basis for planning training in his report on a seemingly

unsuccessful attempt at a training needs assessment for librarians which

employed surveys and a training audit.

Beaumont (2002) analysed search-tracking logs at the

State Library of Victoria to describe the searching behaviour of visitors to

the library and determine the extent to which they were able to learn from

unsuccessful search results and rephrase queries.

Rossett (1987) postulated that TNAs should use a range

of techniques and tools including: extant data analysis, needs assessment and

subject matter analysis, interviews, observations, group discussions and

surveys. Employing a variety of methodologies can shed light on different

aspects of the TNA including optimal performance, actual performance, the

causes of sub-optimal performance, feelings about tasks and potential

solutions.

Drawing on the work of Beaumont’s search log analyses

and Rossett’s variety of methodologies, the library set out to use the

empirical data available to produce a multifaceted view of training needs

within LAQ though a variety of techniques and tools – while avoiding

self-assessment instruments.

Methods: The Five Components

of LAQ’s TNA

Catalogue and

Knowledge Management

Database Usage Statistics

The first component of the TNA was an analysis of

query logs generated by our library catalogue and internal knowledge management

(KM) databases. The logs provided empirical data about the searching behaviours

of LAQ staff when using these resources.

The query logs are automatically generated by our LMS

system and are enabled for our catalogue and all client facing internal KM

databases. The logs capture the following information:

·

date of search;

·

start and end

time of search;

·

IP address of

searcher;

·

database

searched;

·

search string;

and

·

number of

results returned

Logs were analysed monthly. The data was imported into

an MS Excel spreadsheet which used a number of formulae to determine where and

when the databases were being used, and what information clients were searching

for. The monthly data was subsequently copied into an annual MS Excel

spreadsheet for the final analysis.

The IP address data revealed whether a user was

located in a Brisbane or regional office. For users in our Brisbane office, we

were able to identify the floor in the building that the search originated

from. Regional users connect to these databases via a VPN connection and

consequently IP address data for these users did not reveal any usable

information about their location.

A search resulting in zero results being returned was

classed as a ‘failed’ search for the purpose of the TNA.

Subscription

Database Usage Statistics

The LAQ library purchases subscription access to a

number of database products provided by three principle external suppliers, as

well as a range of other products from various suppliers. Usage statistics

provided by two principle suppliers, LexisNexis and Thomson Reuters, were

selected for the TNA as they provided the largest datasets.

LAQ uses IP-fixed access to these databases and

consequently statistics could only be obtained for the organization as a whole.

The statistics provided by each supplier varied in scope, range and quality,

but typically included information about the number of searches, document views

and downloads for each individual subscription over a period of time.

Unfortunately, deeper search-level information was not available.

Given the variation in data provided by each supplier,

statistics were analysed manually using MS Excel with separate findings for

each supplier included in the results.

Library

Reference and Research Request Statistics

A core role of the LAQ library is the provision of a

reference and research service to its clients. The scope of this service ranges

from simple reference queries through to complex legal research. An analysis of

the number, complexity and type of requests received by the library provided

insight into the legal research needs of our clients. Through this analysis

some inferences were drawn about the legal research skills required of LAQ

staff, and potential skills gaps that might currently exist.

A record of each reference/research query the library

receives is captured in the library’s reference database. Library staff enter

these records following completion of the request categorising them by

complexity (ready reference, simple or complex) and type (e.g., case law

research; document delivery). The analysis looked for commonality and variation

in request frequency, type and complexity across organizational units and

geographic locations (regional offices). Individual clients were de-identified

in the data and were not included in the analysis.

MS Excel was again used to analyse the raw data

extracted from our research request database.

Work Shadowing

Library Clients

Library staff shadowed library clients in two

different organizational units as they performed their normal duties, providing

qualitative data about: their information use and needs; the resources they

used; the potential gaps between their needs and skills; problems they

encountered when researching; and opportunities for developing training or

services for staff in those organizational units.

The two units were chosen on the basis that the

library staff knew little about their day-to-day work. Team 1 provides

telephone advice to LAQ clients across many areas of law; Team 2 represents LAQ

clients in summary matters in the Magistrates Court.

Support for the shadowing was obtained from the

relevant team managers and the participating library clients, and permissions

were gained from LAQ clients prior to each session.

Four library staff participated in the shadowing, with

a total of five shadowing sessions taking place (two with Team 1, and three

with Team 2). Each shadowing session lasted between 2-4 hours.

Library staff took notes during the sessions and

discussed findings with the library client at the conclusion of the session.

Notes were later collated into an MS Word document, allowing for further

analysis.

Interviewing

Team Managers

Face to face interviews with six team managers were

carried out by library staff to obtain qualitative data on the training needs

of the staff in each manager’s team. Each interview ran for approximately 15

minutes and was attended by the team manager and two library staff.

Managers were emailed two questions to consider prior

to the interview so that they could reflect on their team’s requirements.

Within a context of services provided by the library:

1.

What 3 things do

you really want your team members to be able to do?

2.

Which of these,

if any, do they currently struggle with most?

The manager’s responses to the questions were

discussed in the face to face interview. Where required, follow-up questions

were used during the interviews to clarify or expand on answers given, and to

discover whether the manager could provide recommendations on the preferred

format and timing of future library training.

Library staff made notes during each interview which

were then collated into an MS Word document, allowing for further analysis of

responses.

Results

Catalogue and

Knowledge Management Database Usage Statistics

General

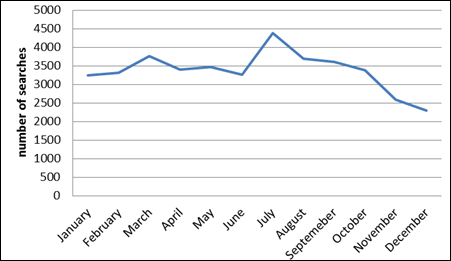

The full dataset for the TNA comprised 40,389 searches

across our catalogue and 11 KM databases. Time and date analysis showed fairly

constant usage throughout the working day but some seasonal variation during

the year. Ninety-eight per cent of searches were conducted between 7am and 7pm.

Of the remaining 2%, searches were performed in all hours except from 2-3am.

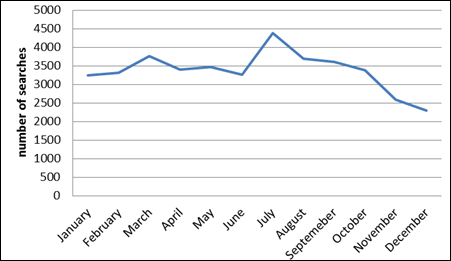

Monthly usage varied from 2,299 searches in December to 4,376 searches in July.

Usage did not correlate with school terms – July and

September, which contain school holidays, were busy months; November – which

does not contain school holidays – gave the second fewest number of searches

(see Figure 1).

Figure 1

Total searches logged (2014).

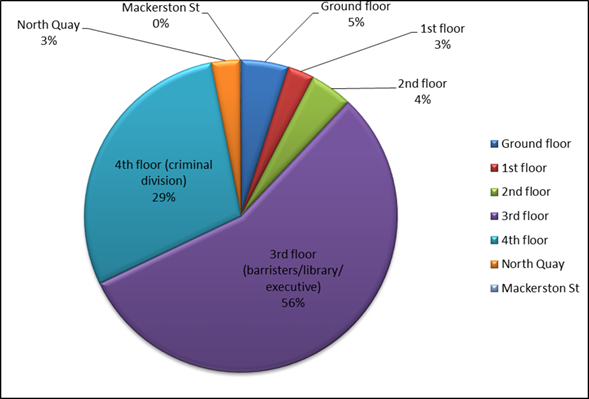

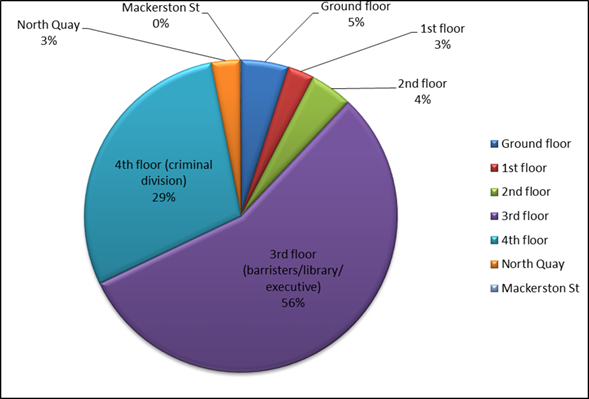

Seventy per cent of searches originated from the

Brisbane offices, where 70% of LAQ lawyers are located.

For the Brisbane searches logged, 85% originated from the

3rd and 4th floors which house the criminal division and in-house counsel

(barristers), the smaller executive and policy units, and the library – see

Figure 2. The remaining 15% of searches were dispersed across three floors in

the main Brisbane office and two annexes (North Quay and Markerston Street).

These locations house LAQ’s family and civil law divisions, and other

administrative units.

Interpretation of training issues. There was considerable variation in search numbers between months. If

trends appear over time, consideration should be given to scheduling training

for the quieter months of the year. Monthly usage figures challenged our

perception that school holidays are our quietest periods. However, further

analysis of a larger dataset would have to be analysed to confirm usage trends

over time.

The 30% of legal staff located in regional offices

executed 30% of searches of the library’s databases. This indicates that there

is a continuing need for library staff to provide training and point-of-need

support to regional offices through appropriate and convenient channels.

Training priorities need to be aligned with the needs of teams and divisions

which use library resources the most, i.e. the criminal practice and in-house

counsel. However, low usage by other teams must be interpreted in the context

of the relevance of our knowledge management databases to their areas of

practice. For example, we would expect the use of our KM databases to be much

higher for the criminal appellate specialists, who make detailed submissions in

higher courts, than for duty lawyers appearing in the Magistrates Court who

have minimal time to prepare for their appearances.

Figure 2

Location of users - Brisbane offices.

Interpretation of additional issues. The relatively even spread of queries across business hours indicates

that reference staff must always be available to assist and advise clients

during business hours.

While the bulk of searches occur between 8am and 5pm,

consideration should be given to whether we can provide after-hours support

without compromising the library staff’s work/life balance.

Catalogue Searches

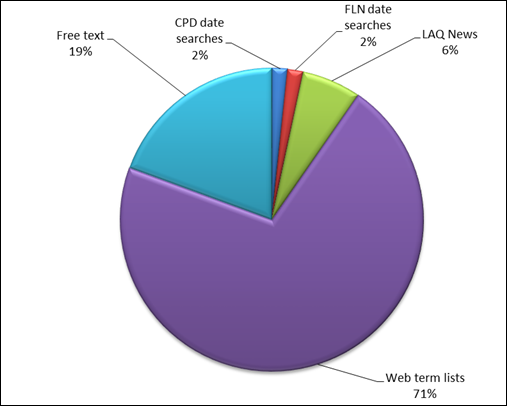

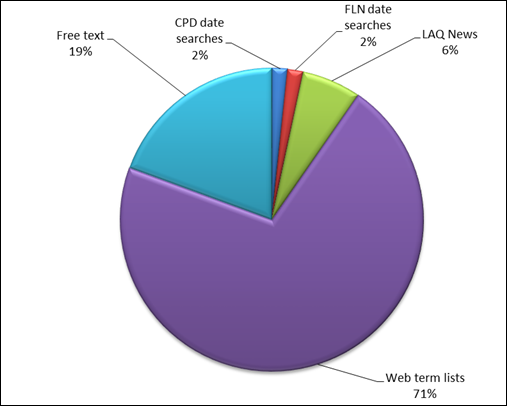

The dataset of catalogue searches comprised 21,490

queries.

These searches fall into five distinct categories,

including:

·

free text using

a traditional catalogue search form on the LAQ Intranet;

·

predefined

searches via web term lists (130 links on the library’s Intranet pages to collections

of key resources by topic, and curated by library staff);

·

predefined

searches for continuing

·

professional

development (CPD) resources;

·

predefined

searches for our Family Law Notes (FLN) current awareness service; and

·

predefined

searches for specific catalogue records via an LAQ News feed on the homepage of

the organisation’s Intranet (see Figure 3).

Figure 3

Categories of catalogue search.

Of the web term list searches, 28% were to legislation

topics and 25% to case law topics. Sixteen of the 130 web term lists were not

searched at all in 2014.

Free text searches via catalogue search form. Our catalogue search form has four main fields –

Global Search, Title, Author and Subject, and three other limiting fields –

Date, Type (e.g. book, journal) and Format (e.g. electronic, paper). When users

performed a free text search using the Intranet search form 96% used a single

search field only. Overall, free text

searches produced a 15% failure rate (i.e. searches returning no results). The

Author field yielded a 2% failure rate while title and subject proved less

successful with 27% and 30% failure rates respectively. When two fields were

searched the failure rate reached 31%.

The ability to do a global search was introduced in

October 2014 and was used in 247 searches with a failure rate of 19% to the end

of 2014.

In February 2015, the database search forms were

rewritten to comply with current web standards and overcome some UX issues.

Following this change the overall failure rate dropped from 15% to 3.5%.

Interpretation

of training issues. The dramatic

fall in failure rates for searches following recoding of search pages, coupled

with the relatively low usage of the catalogue search form suggests that

training in effective searching of the library catalogue should be a low

priority.

Figure 4

KM database searches by area

of law.

Interpretation

of other issues. The popularity

of predefined searches suggests that the users are relying on web term lists to

access library resources in preference to searching the catalogue manually.

These topics need to be reviewed systematically to ensure they remain relevant

and current. Additionally, the time the library invests in current awareness

emails and web news items is worthwhile since we can clearly demonstrate that

staff access library resources via these routes.

Our analysis of web term list use showed that a number

of key topics including legislation and case law were heavily used. There is

scope to review the less ‘popular’ topics. This may involve reducing the number

of topics, amalgamating and relabelling topics, and adding new topics.

KM Databases

Ninety-two per cent of the 16,984 searches of LAQ’s KM

databases were to criminal law databases. Searches of the library’s Criminal

Judgments and Comparable Sentences databases accounted for 79% of searches. A

further 3% were to general databases e.g. legislation, and only 5% of traffic

was to civil and family law databases combined – see Figure 4.

Of the 9,176

searches of the Criminal Judgments database, 42% were executed by users

clicking on links to predefined searches such as current awareness emails sent

to staff in the criminal law division.

Manual searches of the Criminal Judgments database via

a search form on the library’s Intranet page resulted in a total failure rate

of 18%. Searches using specific fields

had varying success rates. For example, the Court field had a surprisingly high

66% failure rate; Court Number 21%; and Decision Date 25%.

The Comparable Sentences database has a complex search

form that allows users to perform searches matching very specific criteria.

However, 90% of searches used only a small number of the available fields

including Charge, Age, Criminal record and Plea. Twenty-one per cent of

searches were limited to appeal sentences (see Table 1).

Table 1

Adult Comparable Sentences

Database - Search Fields Used in Manual Searches

|

Field

|

% of total searches

including this field

|

|

Charges

|

90%

|

|

Age of offender

|

41%

|

|

Under 25 - y/n

|

39%

|

|

Criminal record

|

34%

|

|

Plea

|

34%

|

|

Appeal sentences

|

21%

|

|

Court

|

20%

|

|

Particulars and comments

|

9%

|

|

Noncustodial sentences

|

6%

|

|

Full text

|

6%

|

|

$ value of property

|

5%

|

|

Armed

|

5%

|

|

Alcohol/drugs

|

4%

|

|

Sentence date/range

|

3%

|

|

Offences in company

|

2%

|

|

Known to accused

|

2%

|

|

Gender

|

2%

|

|

Cooperation with

authorities

|

2%

|

|

Employed

|

1%

|

|

Psych problems

|

1%

|

|

Dependants

|

1%

|

|

Previous convictions

|

1%

|

|

Judge

|

<1%

|

|

Aboriginal/TSI

|

<1%

|

The overall failure rate for the Comparable Sentences database

was 33%.

Interpretation of training issues. There are clearly implications for training in the high failure rates

when using the Comparable Sentences database, and to a lesser extent the

Criminal Judgments database. Changes to database search forms implemented in

2015 saw a reduction in the number of failed searches, however the 2014 TNA

results suggest that strategies to improve this situation should include more

regular training in using the database, and further investigating search form

UX/functionality changes to help eliminate specific searching errors.

While it is understandable that fields such as Charge,

Age, Criminal record, Plea and Court would be the most-searched fields in the

Comparable Sentences databases, low usage of other fields suggests that further

training is needed in performing more complex searches.

Interpretation of other issues. In addition to extra training, the high failure rates for manual

searches of the Comparable Sentences and Criminal Judgments database may be reduced

further by exploring search form UX/functionality changes to help eliminate

specific searching errors.

The high percentage of traffic to criminal law

databases supports the library’s policy of directing the largest proportion of

our time to maintaining and developing databases in this area.

The high occurrence of predefined searches in our

Criminal Judgments database indicates current awareness services to our

criminal lawyers are widely used. Provision of these types of service should be

continued. Consideration should be given to what improvements in the scope and

relevance of such services might be made.

Subscription

Database Usage Statistics

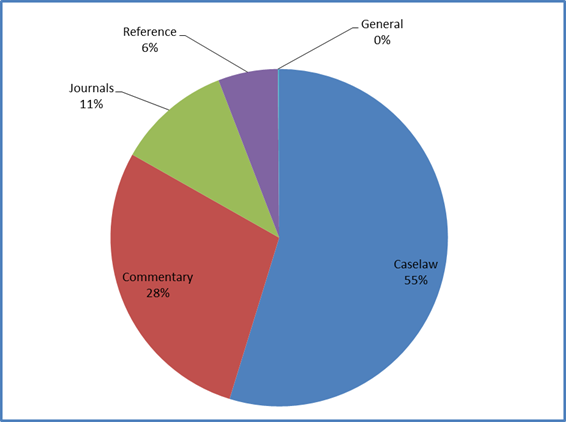

Thomson Reuters

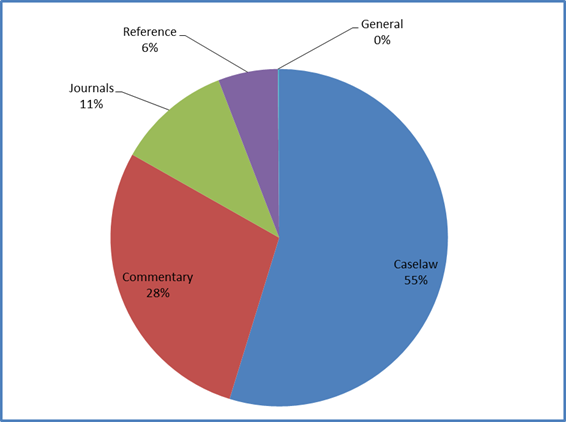

The highest usage of Thomson Reuters was for accessing

case law (55% of searches) and commentary (28%) – see Figure 5. Journal usage

at 11% of the total was relatively low in comparison.

Usage figures (see Figure 5) show that for most

products, users were likely to look at only one or two results following each

search. Exceptions to this were Unreported

Judgements searches where the average was over two cases, and civil law

commentary publications, where only around half of the searches performed

resulted in viewing of a document in the search results.

The rates at which users downloaded documents they

viewed were generally low – 4% for case law and journals, 14% for commentary

and 27 % for the legal encyclopaedia Laws

of Australia.

No data was provided for searching verses browsing of

publications on Thomson Reuters.

Figure 5

Thomson Reuters searches by content type.

Table 2

Thomson Reuters Views as

Percentage of Searches

|

Subscription

|

Views as % of searches

|

|

Reference

|

128%

|

|

Laws of Australia

|

123%

|

|

Lawyers Practice Manual

|

138%

|

|

Commentary

|

145%

|

|

Criminal

|

149%

|

|

Procedure

|

157%

|

|

Civil

|

57%

|

|

Journals

|

138%

|

|

ADRJ

|

141%

|

|

Qld Lawyer

|

135%

|

|

Family law review

|

152%

|

|

Criminal law journal

|

129%

|

|

ALJ

|

192%

|

|

Caselaw

|

114%

|

|

Firstpoint

|

96%

|

|

Unreported judgments

|

239%

|

|

Law reports

|

107%

|

LexisNexis

For all types of publication except commentary

services, searching accounted for greater than 90% of interactions. For

commentary services searching was still dominant but was reduced to 62% – see

Figure 6.

Figure 6

Searching vs browsing of

publications on LexisNexis.

Figure 7

Percentage of research

requests by complexity (2014).

The figures for searching verses browsing by subject

were very similar, with searches accounting for 90% of behaviour for all

subjects except criminal law. The library subscribes to 29 titles on LexisNexis

yet Carter’s Criminal Law of Queensland

accounted for 26% of all interactions.

Interpretation of training issues. Usage figures for subscription services show that the most critical information

needs of the library’s clients are finding case law, and to a lesser degree

legal commentary. Therefore, these should be the focus for training activities.

While journal use was significantly lower than for

other resources, this was not unexpected given that the legal practice is

focused on service provision rather than academic research. Journal usage

should however be benchmarked against similar organisations.

Figures for viewing documents on Thomson Reuters show

that, on average, users are finding one or two results per search worth further

attention. This figure is reasonable for locating commentary on a particular

section of legislation, or locating specific cases. The figure is low however

for situations where users are looking for cases on a point of law, for example

via FirstPoint or Unreported Judgments. This again

suggests a need for providing more training in case law research.

Download rates on Thomson Reuters are quite low.

Without past results for comparison, more investigation is needed to understand

this figure. There may be issues with effective search techniques that could be

addressed with training.

The LexisNexis data showed that users browse

commentary services much more frequently than they do other kinds of online

publications. One possible explanation is that users are less comfortable

searching for commentary and continue to use online commentary services like

print resources. This hypothesis needs to be tested through follow up research.

Interviewees (in component 5 – Interviews with Team Managers) however also

reported that they wanted more training in using commentary services,

supporting this theory.

Library

Reference and Research Request Statistics

Seventy-four per cent of research requests received in

2014 were classified as simple such as requests for specific legal cases or

legislation, and simple catalogue or comparable sentences searches.

Twenty-three per cent were classified as complex – see Figure 7.

A quarter of the requests came from regional offices,

a quarter from the civil and family law divisions combined, a quarter from the

criminal law division, and 15% from our in-house counsel. The 10 teams who used

us most came from across all the legal divisions and the executive management

team.

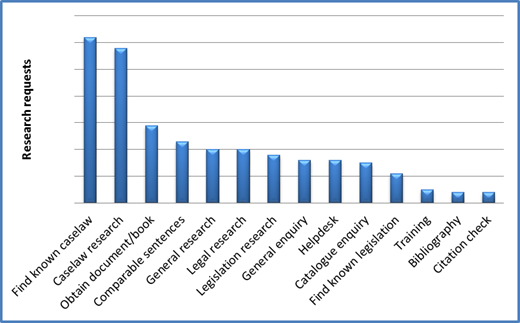

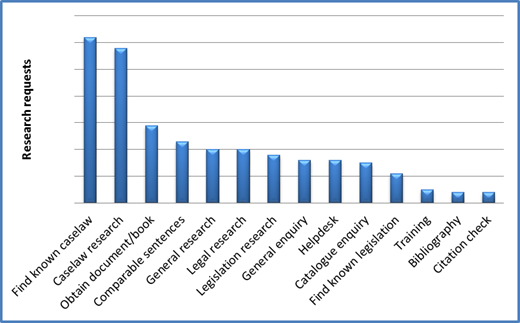

Figure 8 shows the types of requests received in 2014. Nearly half

related to case law research; 10% were legislation related; and 7% were more

general legal research requiring a mix of primary and secondary legal sources.

Figure 8

Types of research requests received (2014).

Interpretation

Training

issues. The high percentage of simple reference queries indicates that there is

still a need for training in basic library and research skills. Further, the

majority of requests involved case law and comparable sentences research, again

indicating that we should be concentrating our training efforts in these areas.

Other

issues. Analysis of reference queries by teams shows that teams which use us

the most come from all divisions and locations confirming that we need to

provide training and convenient communication channels across the organization.

Additional promotion of library services could increase the use of the

library’s research services amongst low use teams including regional offices.

Work Shadowing Library Clients

Library staff performed five work shadowing sessions with library

clients in two different organizational units. All four library staff members

expressed a desire to participate in work shadowing both teams selected for the

2014 TNA. Sessions were organized following the shadowing where library staff

could discuss their observations and impressions.

The responses from clients in both teams were similar. Lawyers in these

teams have limited time for legal research. Observation of interactions between

the lawyers and their clients confirmed that they rely heavily on experience

and prior knowledge of the law to provide efficient quality advice and

assistance to their clients. Clients in the telephone advice team identified a

need for current awareness services which covered State and Commonwealth

legislation and case law relevant to their practices.

Interpretation

Training

issues. The responses from the shadowing sessions made it clear that there is

little need for library training for clients in these particular teams, other

than the need for relevant current awareness services.

The level of engagement and enthusiasm the library staff showed for this

exercise however indicated that work shadowing is a worthwhile professional

development opportunity for library staff. It increases the staff’s knowledge

of the business of the organisation and therefore should be included in annual

performance agreements.

Other

issues. The shadowing sessions showed that lawyers in these teams need

up-to-date skills and knowledge to provide advice and representation. The range

of legislation and case law alerting services from commercial and government

sources however is overwhelming and few are sufficiently customisable.

The Library identified legislation updates as a service we could provide

to our clients, and consequently created a database of recently updated

legislation of relevance to LAQ’s areas of practice. Updates containing a link

to a predefined query of the legislation database are emailed to library

clients each week. Access to the database is also available from our Intranet.

The email alerts summarize the changes to relevant legislation, and provide

links to primary sources such as the Bill and Act as Passed, and secondary

sources such as history of the legislation.

Interviewing Team Managers

Six team managers (approximately 10% of legal team managers) from across

the organization were interviewed, and the findings from these interviews were

subsequently analysed.

All the interviewees expressed a requirement for case law training, and

half mentioned comparable sentences training specifically. Some interviewees

also suggested training in researching legislation; basic general research

skills; and effective searching of commentary services was also needed. Most

managers reported however that their teams were already competent at

researching legislation.

One manager reported that they would rather come to the library for help

with complex research than getting training in advanced research skills.

Other issues raised included knowing what resources were available from

the library and the need to keep legislation and case law knowledge current.

Managers were also asked about their teams’ preferred mode of delivery.

None of the interviewees expressed an interest in self-paced web-based training

videos, such as webinars.

All interviewees indicated that CPD points were an incentive to attend

training, and 15 minute sessions within team meetings were also requested.

Additionally, managers provided information about the times of day that would

result in higher participation rates.

Interpretation

Training

issues. The library should provide regular training on case law and comparable

sentences research in a mixture of formats from 15 minutes to 1 hour to cater

to all teams’ schedules. Additionally, basic skills training in legislation and

commentary services should be made available regularly.

Library staff need to liaise with team managers when scheduling training

and provide sufficient notice of future training sessions.

Consideration should be given to tailoring course content to specific

teams, rather than the current tendency for generic training.

Discussion

Through the TNA process the library was able to elicit data about the

actual searching and browsing behaviour of staff; their skills levels and

research needs; and to identify gaps between actual and ideal performance by

using a range of data sources. These included a mix of empirical data (database

usage statistics), subject matter analysis (research requests) and

observational evidence (job shadowing and interviews). The combination of these

techniques provided a more complete and accurate analysis than could have been

achieved through any single methodology.

Some components provided unique insights into training and other issues.

For example, Catalogue and KM database usage analysis revealed the scale of a

usability issue with the library’s database search forms for which we were

subsequently able to develop a technical solution. Client interviews provided

very specific data about optimal skill requirements and scheduling of training

programs that would otherwise have been unknown to library staff planning

future training.

Certain themes recurred throughout the components. Effective case law

research was shown to be the most important skill for lawyers. In-house counsel

and criminal law teams were shown to be our biggest users and their research

tools the most frequently accessed.

The evidence provided by the TNA supported some assumptions the library

had, for instance that the in-house counsel’s primary need was for high quality

case law research and that the criminal law practice needs ongoing training in

case law, comparable sentences and commentary services. It showed us we were

underestimating some user behaviours such as how much users searched online

subscriptions (compared to browsing). It also gave some unexpected results such

as how difficult users find searching particular internal database fields.

The TNA relied on data that was readily available to us. However, it

took considerably more time to complete the analysis than was estimated at the

project’s outset. Subsequent TNAs however will be simpler and quicker because

the development work has now been done including:

- determining

appropriate TNA components and documenting methodologies;

- designing

spreadsheets to automate query log and research query analyses; and

- retrospectively

classifying research requests to allow TNA analysis.

The analysis of 2014 data was distilled into a training needs analysis

report, the first of an annual series. The annual report will provide a sound

evidence base for developing a training program in 2015 and beyond.

There have been a great number of other benefits beyond the library’s

training program, including:

- senior

management awareness of library services;

- evidence

for demonstrating the library’s value to the organization;

- improved

reporting of library usage statistics;

- improved

relationships with library clients;

- highlighting

of UX issues with internal databases; and

- professional

development for library staff.

Future Developments

The TNA has produced results that we can translate into action. Our next

step is to review our training schedule and develop and deliver training

activities based on the results of the TNA. We will also continue with a

program of internal database redevelopment to improve the manual searching

experience for library clients.

The 2014 TNA has provided sufficient value to schedule it for the first

quarter of every year. The library

however is not sufficiently resourced to perform every component of the TNA

each year. Including fewer components per year will allow us to analyse the selected

components more deeply. For instance, analysis of ‘failed searches’ or

individual subscription titles usage could be included some years.

Query logs are harvested every month. They produce meaningful data

through automatic analysis, and therefore will be included in the TNA each

year. The statistical spreadsheets will be updated to accommodate changed

search parameters and measure their impact.

Work shadowing provided an opportunity for developing a new service but

revealed little about how lawyers use information resources on the job. Future

shadowing should include teams with more complex legal research needs.

Future TNAs may include online user surveys. Future annual training

reports will also include trend analysis across years. Of particular interest

are:

·

trends in database

usage including predictability of monthly peaks and troughs;

·

changes to search

failure rates and sophistication of search behaviours;

·

changes to

subscription usage patterns; and

·

changes to the rate

or types of reference queries especially in subjects targeted by training.

Further, we should experience an increase in participation in training

sessions if we can better target and schedule training sessions.

Conclusion

The process developed for a multi-component TNA successfully met the

objective of describing training needs within LAQ as an evidence basis for

developing training activities. The five components provided a mix of

empirical, observational and anecdotal evidence and produced a multi-faceted

picture of training needs at LAQ. The library will use the results to develop a

program of training aligning with our client groups’ needs and skills gaps. The

process will be repeated annually to describe trends and provide insight into

the effectiveness of training efforts.

References

Allred, J.

(1995). Co-operative training, open learning and public library staffs: interim

report November 1992 and final report February 1994. Library Management, 16(4),

46.

Beaumont,

A. (2002). The 3 bears - not too big, not too small, just right or how search

access logs can be used to improve success rates for searchers. In Proceedings from E-Volving Information Futures,11th

Biennial Conference & Exhibition 1. (pp.

229-254). Port Melbourne Vic: Victorian Association for Library Automation.

Bresnahan,

M. M., & Johnson, A. M. (2013). Assessing scholarly communication and

research data training needs. Reference

Services Review, 41(3), 413-433. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/RSR-01-2013-0003

Johnson, A.

(2005). Training the trainees: developing effective programmes and partnerships

in legal practice. Legal Information

Management, 5(1), 34–41. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S1472669604002324

McGehee,

W., & Thayer, P. W. (1961). Training

in business and industry. New York: John Wiley & Sons.

Oldroyd, R.

(1995). Staff development and appraisal in an "old" university

library. Librarian Career Development,

3(2), 13-16. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/09680819510083435

Rossett, A.

(1987). Training needs assessment.

Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Educational Technology Publications.

Turner, A.,

Rosen, N., & Wilkie, F. (2003). Joining forces: developing a network to

raise awareness of digital library resources in health care. VINE, 33(4), 161-167. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/03055720310510873

![]() 2015 Davies and Vankoningsveld. This is an Open

Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

2015 Davies and Vankoningsveld. This is an Open

Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.