Research Article

Small Library Research: Using Qualitative and

User-Oriented Research to Transform a Traditional Library into an Information

Commons

Quincy D. McCrary

Associate Librarian

The Carl Gellert and Celia

Berta Gellert Library

Notre Dame de Namur

University

Belmont, California, United

States of America

Email: qmccrary@ndnu.edu

Received: 1 Dec. 2016 Accepted:

6 Feb. 2017

![]() 2017 McCrary. This is an Open Access article

distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

2017 McCrary. This is an Open Access article

distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

Abstract

Objective

- The

project team investigated the changes necessary to transform the original

library into an information commons. The researchers sought to drive the

project by asking for patrons’ input, rather than rely on the vision of

administrators or librarians.

Methods

- The

project team used four techniques to gather data. They recorded patron use

patterns, administered surveys, conducted formal interviews, and facilitated

comment boards.

Results

- Each of the four methods used in this research

delivered similar conclusions. Patrons used the library as a study hall, but

the space did not facilitate collaboration. Patrons requested more group study

spaces, more access to power, and a quieter environment. Patrons identified the

value of developing a learning community in the library. Finally, patrons

advocated for the retention of physical collections in the library building.

Conclusion - The present

library building, designed to facilitate individual, quiet, textual based

learning, no longer serves the needs of its patrons. Analysis of this project’s

data supports the need to develop an information commons. The Gellert Library

is not just a place to store books and study. Rather, it is a place where

meaning and learning emerges from access to knowledge.

Introduction

The educational

mission of Notre Dame de Namur University (NDNU) embraces the idea of holistic

learning communities. At NDNU, learning communities develop when incoming

classes of students engage in pod learning environments. In this model,

sections of the same class come together periodically across a semester for

large group learning activities like community engagement, special topics, and

speaker series. An information commons model for the library that embraces

collaborative information seeking would enhance pod instruction and help build

learning communities. The University Provost, along with the Library Director,

articulated a clear need for the library to transform into an information

commons. The Library Director formed a team including a project leader (a

formally trained anthropologist), the Library Director, and three student

assistants to complete this project. The project team attempted to discover

what modifications to the library’s space could transform it into a modern

information commons.

Literature Review

Librarian Donald Beagle

best described the notion of an information commons as a facility designed to

organize workspace and service delivery around the integrated digital

environment (Beagle, 1999). It includes the physical commons where open floors

and browsable stacks allow quick access to information and collaboration, the

virtual commons where users access the vast digital content of the library, and

the cultural commons of research collaborations, workshops, and tutorial

programs (Beagle, 2011). Originally developed in the 1980s, the information

commons concept emerged in different forms in the 1990s (for example as an

information hub, media union, or a learning commons). In 2010, Steven Johnson

presented a TED talk titled “Where Good Ideas Come From: The Natural History of

Innovation.” Here Johnson explored the role of the coffeehouse in the

Enlightenment, arguing it provided "a space where people would get

together from different backgrounds, different fields of expertise, and share"

(as cited in Holland, 2015). In many ways, this mirrors what an information

commons is attempting to create in libraries today. Today, an information

commons fosters an environment centred on the creation of

knowledge and self-directed learning rather than an isolated user accessing

information (Rawal, 2014). The earlier reader-centred paradigms led to

spaces that championed collections and a “well lit area for reading” (Bennett,

2009, pp. 181-182). Technological changes over the last few decades have resulted

in a substantial move of information from print to digital. This allowed

libraries to re-appropriate areas once dedicated to bookshelves for more

user-oriented spaces (Heitsch & Holly, 2001). Sarah Hutton in the “Final

Report of the Learning Commons Assessment Task Force for the University of Massachusetts (Amherst)” notes

that “a space has evolved from a combined library and computer lab into a

full-service learning, support, research, and project space” (Hutton, 2015, p.

10).

The turn to qualitative

studies of libraries is a relatively new practice. Sandstrom and Sandstrom

(1995) were some of the first researchers to identify a need for qualitative

research in libraries. Ethnographic studies of university students in general

are also limited, with the exception of Michael Moffatt’s (1989) study of

students at Rutgers University titled “Coming of Age in New Jersey: College and

American Culture.” Susan Blum’s research published as “My Word!: Plagiarism and

College Culture” (2009) is an ethnographic examination of plagiarism in student

assignments. Cathy Small’s “My Freshman Year: What a Professor Learned by

Becoming a Student” gives an account

of student life at Northern Arizona University based on her own experience

enrolling as a “returning” student (published as Nathan, 2005). In the

mid-2000s several projects using ethnography to understand library users’ needs

and behaviors resulted in very good projects such as Bryant, 2007, 2009; Foster

and Gibbons, 2005, 2007; Jahn, 2008; Ostrander, 2008; Othman, 2004; and Suarez,

2007. Nancy Fried Foster and Susan Gibbons at the University of Rochester

(Foster & Gibbons, 2007) conducted one of the first large-scale

ethnographic studies of how students utilize the library in 2004–2006. The

tremendous success of this study in uncovering the details of student life

drove many librarians to conduct similar studies. Fresno State University

conducted an excellent ethnographic study (Delcore, Mullooly, & Scroggins,

2009). Smale and Regalado (2010) have begun publishing work conducted in the

CUNY Libraries in the Undergraduate

Scholarly Habits Ethnography Project. Head and Eisenberg in “Lessons

Learned: How College Students Seek Information in the Digital Age” (2009) seek to understand student

information-seeking behaviors at many colleges and universities across the

United States. The influential “So You Want to do Anthropology in Your

Library?: A Practical Guide to Ethnographic Research in Academic Libraries” (Asher & Miller, 2010) provided a

benchmark and toolkit for further ethnographic research of libraries. Lastly,

Khoo et al. (2012) do an excellent job summarizing the current state of

qualitative research used in the study of libraries.

Aims

The Notre Dame de Namur University library is

a single 40,000 square foot room. A second story balcony over three quarters of

the floor houses the book collection. Prior to the alterations brought about by

this project, students using the library tended to work individually. Group

work was conducted at large tables in hushed whispers that often carried

throughout the building. The noise from older keyboards in the computer lab

area could dominate the building with frenzied typing. Instruction sessions that

promoted active learning disrupted the entire building. As a result, speaker

sessions, presentations, open microphone nights, etc., were rarely scheduled.

The library building, due to its structure and technology, did not promote a

collaborative information seeking and learning environment. The research team

for this project sought to discover, using a four technique method, how to

create such an environment. The primary research question was, what changes could

convert the library into an information commons?

Methods

In 2014, the Internal Review Board for NDNU

approved this research and any publication of the work. Utilizing a

qualitative approach, the project team employed four techniques to build a

holistic snapshot of user needs. These four techniques were

·

Recording

Patron Use Patterns - logging of users’ place and activity in the building.

·

Surveys - measurements of what

services are being used and ranking satisfaction with them.

·

Formal Interviews - following an

interview guide and used to illicit a broader response.

·

Comment Boards - self-reported

responses to questions and prompts.

The data collected included

how patrons use the library, the ways they seek help, and their interactions

with library spaces. Participation in this project was voluntary. The project

leader informed respondents about their right of consent. Over 300 respondents

participated in this project.

The research

spanned the 2015-2016 academic year. Patrons completed surveys advertised

through the library’s website and through signage in the library. Staff

requested that patrons who completed the survey take part in a formal

interview. The project leader conducted 24 formal interviews in a small office

in the main library building. The interviews followed a guide (see Appendix C).

The project leader then transcribed the interviews. The project leader and two

designated assistants recorded patrons’ location, study type (individual or

group), and technology use every hour the building was open. At different

periods during the 2015-2016 school year, large comment boards (located in

three key points in the library) displayed alternating questions. Patrons

self-reported directly on the comment boards.

Results

Each of the four

methods used in this research resulted in similar conclusions. Patrons used the

library as a study hall, but the space did not facilitate collaboration.

Patrons requested more group study spaces, more access to power, and a quieter

environment.

Recording

Patron Use Patterns

Who uses the library, how

do they use it, and why? Over the fall semester in 2015, the project leader and

two assistants observed and recorded patrons in the building at one-hour

intervals. The project leader developed four categories for recording use

patterns.

·

Students working individually

·

Students working at library computers

·

Total number of students working in groups (and total groups)

·

Total number of laptops in use

Library staff

generated a map of the floor and used various symbols to describe the

categories outlined above (see appendix A). Data from this recording process

showed that patrons use the library as their main study hall and collaboration

space. Within 15 minutes of opening and until closing, patrons used the library

to work independently and in groups.

Students working on personal laptops, who did not use a computer

terminal at the time of observation, made up 74% of patrons using the library.

Students working in groups located at large tables made up 37% of patrons,

while 29% used library computer terminals. Students working alone made up 62%

of patrons, and 58% percent used a library terminal. The library space includes

large tables, small tables, and individual carrels. At intervals throughout the

day/evening, patrons occupied all locations.

Survey

Who uses the library, how

do they use it, and why? A survey of library users provided a range of

information about user preferences and behaviors. Staff administered the survey

virtually, via the library website and the campus digital news source “NDNU Pulse.”

The student body at Notre Dame de Namur is relatively small at just under 2000

students. Patrons completed over 300 surveys, representing nearly 15% of

possible respondents. A copy of the survey is included in Appendix B.

Use

The survey measured how often patrons reported using specific features and

services of the library. Meeting with a librarian was the most frequent service

used, followed by using the book collection, using a computer for academic

work, getting research help, using WIFI, using copiers, using a power outlet,

and studying alone. Patrons reported finding a reserve book, studying in a

group, printing, and scanning less frequently, followed by meeting with a

tutor/professor, using a table, using a computer for non-academic reasons, and

meeting with friends. As should be expected, the microfilm/microfiche

collection showed the least amount of use. The high frequency of “meeting with

a librarian” speaks well of the library’s integration into the curriculum, and

to the value of patron-oriented service to the library’s users.

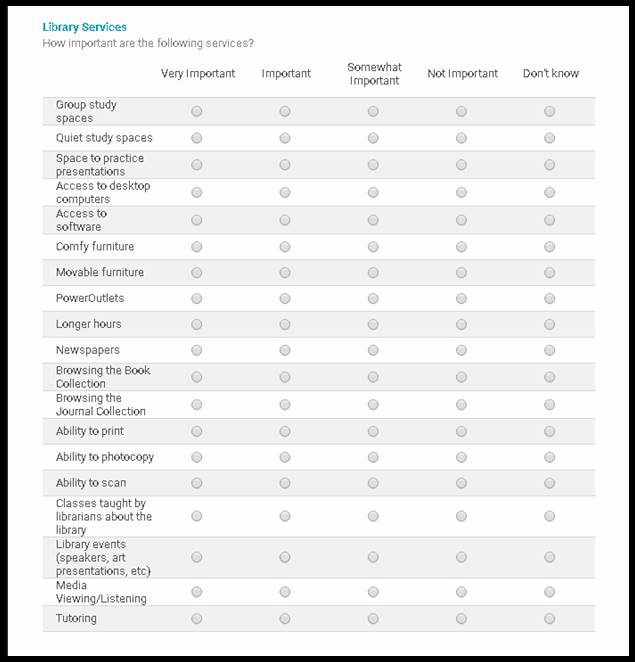

Importance

The survey attempted to measure how important specific features and services

provided by the library are to its users. Survey respondents ranked the need

for quiet study spaces as very important, followed by meeting with a librarian

and attending a library class. Next in importance were a desire for longer

hours, power outlets, group study spaces, access to desktop computers, more

comfortable furniture, a browsable journal collection, printing services,

access to software, moveable furniture, scanning, photocopying, and an oral

presentation practice space. Browsing

the book collection ranked lowest, yet it was still a 29% favorability ranking.

Respondents commenting on open discussion boards also ranked the need for quiet

study space as the highest priority for users.

Satisfaction

The survey prompted users to identify how satisfied they are with specific

features and services of the library. Respondents ranked satisfaction with

librarians the highest. Users were also very satisfied with the library

databases and the borrowing desk. Users were unsatisfied with the quality of

WIFI, the quality of the library collection, access to power outlets, and

lastly they were not happy with their access to the reference desk. High

satisfaction rankings for librarians speaks well of the library’s mission to

provide excellent, hands-on, patron-oriented service.

Interviews

Who uses the

library, how do they use it, and why? Included in the online survey was an option to

conduct an in-person interview. Of the 300 surveys completed, 24 interviewees

were identified. Interviewees were mostly upper-level students: 11 fourth-year,

6 third-year, 3 second-year, 1 first-year, and 3 graduate students. All

participants were from the social sciences and the humanities, including the

graduate students. Interviewees reflected the demographics at NDNU, with a

majority of white females participating. For more demographic information on

NDNU, please see https://www.niche.com/colleges/notre-dame-de-namur-university/. Interviews were

completed in an informal setting (a faculty member’s office) following a

pre-arranged interview guide (Appendix C). The lead researcher, a formally

trained anthropologist, conducted the interviews. As was uncovered using other

methods of inquiry, most students described the same conditions, needs, and

desires about the library. Students noted:

·

The

library is loud

·

There

are not enough group study spaces

·

There

are not enough power outlets

·

The

WIFI is poor

However, one

broad-based question (why is there a library on campus?) elicited many

interesting responses. A key narrative in these comments that did not emerge

from the other data centres on the idea of a learning environment. For example,

respondents noted that libraries are on campus to intrigue and encourage

students. They saw the library as a community centre for learning. One

respondent noted the library is here to “foster the idea of a community of

students who are very into their studies.” Many libraries are adapting from

housing collections to an information commons model, and our users seem eager

for this change. Not only do students want new technologies, they also want to

“enjoy the library as a contemplative oasis” (Freeman, 2005, p. 6). The library

at NDNU is a space where a learning commons is prospering, even within the

constraints of its current physical structure. Students identify with the idea

of a shared community even if they do not always articulate how the library

fosters this concept. Students desire a space they can claim as their own for

the making, creating, learning, and exploring that happens outside of the

classroom. This freedom to create such an academic space makes the library

special, and central, to student life. In many ways, the library acts as a

middle ground between social space, private space, and academic space. Many

interviewees noted how they prefer to come to the library late, after classes

and dinner, and even after socializing. Other interviewees see the library as a

collaborative space, even with the current structure somewhat limiting group

learning. Of the 24 interviewees, 18

commented that the library is a social space in some context, either as a place

to discuss questions raised in the classroom or as a destination to meet other

students and plan activities. Each of these activities helps to build a

community and a cultural space, creating a learning environment that is unique

to NDNU.

Comment

Boards (Flip Charts)

Who uses the library, how

do they use it, and why? At strategic locations throughout the library, library

staff placed large paper flip charts with attached markers, and wrote questions

for patrons to answer at the top of each (Appendix D). Flip charts were

accessible for two weeks at the beginning of each month. Users self-responded

directly on the comment boards. Overwhelmingly, the comment boards revealed

four primary issues:

·

Noise – 28 comments noted a need for noise reduction/quiet space

·

WIFI – 20 comments noted a need for better WIFI

·

Group space – 11 comments noted the need for group study space

·

Power access – 9 comments noted a need for more electrical outlets

Looking at the total

comments noting a need for quiet space, four comments isolated “social noise”

as the primary sound issue (example: “The library is not a hangout it is a place to

read, study, and get work done”). Commenters also requested that library staff

“respect the need for quiet”

and that they “enforced less talking.” The issue of “social noise” is a

challenge for the development of an information commons at NDNU.

Commenters also made specific requests:

·

A

multi-media lab (in process, 2017)

·

A

research lab (in process, 2017)

·

White

boards (added, spring 2016)

·

Glass

boards (test board added, spring 2016)

·

More

large tables (added, spring 2016)

·

More

stuffed chairs (added, spring 2016)

·

Add

TVs with beds and pillows (monitor with

streaming content added, spring 2016)

·

Add

inspirational quotes (new mural about diversity added, spring 2016)

·

Bluetooth

printers (in process, 2017)

·

Get

rid of the smelly carpet by the printers (additional steam cleaning performed,

spring 2016)

·

Provide

better air conditioning (AC replaced, summer 2016)

·

A

snack bar (altered policy to allow food from the cafeteria, spring 2016)

·

A

coffee cart (altered policy to allow drinks from the cafeteria, spring 2016)

·

More

single use desks (added, spring 2016)

·

More

computer stations (additional laptops and iPads added, spring 2016)

·

More

computers just for printing (in process, 2017)

·

More

comfy chairs (added, spring 2016)

·

Hooks

in the bathrooms for book-bags (in process, 2017)

·

More

light, stay open later (added additional hours, spring 2016)

·

Open

the library earlier (added additional hours, spring 2016)

·

Unlimited

printing (students now receive 500 pages free)

·

“Bathrooms that don’t look

like insane asylums” (in

process, 2017)

·

“Please

remove the gum from the walls where the individual desks are” (completed,

spring 2016)

Discussion

What modifications to the

library’s space could transform it into a modern information commons?

Determining how often patrons use library facilities is critical to envisioning

the library’s future. Realizing that this is no small task, the methods proposed

by the project leader provided a viable alternative to simple daily data

collection (i.e. door counts, etc.). The use of libraries has changed over time

from primarily textual study to collaboration and digital information seeking.

Performing patron use studies provides the evidence necessary to make effectual

decisions about how facilities should be changed or modified to meet the needs

of an ever-changing patronage.

From early on in the

process, library staff conducting the patron use recording found that the

library is a highly used study space, especially by individual students. These

data enabled the library to justify the need for additional group study spaces

and, we hope, will lead to a major renovation to facilitate active,

collaborative learning. The library is the only space on campus dedicated to

studying. When asked what other spaces were available for studying, residential

students (those who live on campus) chose their apartments. However, students

who commute to campus dismissed alternatives to the library such as the

Commuter Lounge or the Writing Center. For example, one interviewee noted “I

would probably try and study in the [writing] center, but I find it is really

too noisy in there sometimes, it is not like the library because it is too

enclosed. I can’t even take tests in

there either…I mean the new building is nice but I would rather be in the

library.”

Scholarly evidence notes

how physical book circulation has declined over the years (Allison, 2015). When

students responded about the value of having book stacks in the library, a wide

range of discussions emerged that centred on the idea that

the presence of books helps students feel like the library is a place of

knowledge and learning. One student noted during an interview, “It makes me

feel like I am being productive, you know, that’s why I like being in the

library…you are surrounded by a lot of knowledge, so it makes me feel more

motivated; it motivates you.” While today's academic library users browse books

less, they still value the possibility of doing so.

Outcomes

The findings from this study resulted in many improvements for patrons at the

Gellert Library. Responses provided by students on the comment boards gave an

excellent list of minor and major problems. The survey’s results showed what

services are valued, and how satisfied users are with the library building.

Following users’ suggestions, library staff relocated the information desk to a

more central area in the building. The reference print collection, substantially

reduced and merged into the main circulating collection, is now nearly

non-existent. Its removal created a lot of space around the information desk.

This allowed for the relocation of more comfortable seating, taken from a

“reading room” in the rear of the building, to the reference area. Large tables

are on one side of the building, with smaller round tables located around the

reference desk. These few changes have substantially altered the way that

students use the reference area. Increased reference desk use statistics,

including more one-on-one collaborations, proves this renovation was useful to

patrons. These changes helped to create a physical information commons in the

Gellert Library.

Capital improvements on campus resulted in the library having improved access

to the campus electrical grid and internet. A fibre optic backbone,

completed over the summer of 2015, dramatically increased the quality of the

campus network. Library staff installed three 885-joule surge-suppressing power

strips to a central, curved partition called the “art wall.” This provided

power access to an area of the library that previously had none. Each wall

outlet positioned adjacent to a study area had surge-protecting wall taps

added. Not only did this add power outlets to the floor, but each also included

multiple USB ports for peripheral charging. Improved dedicated carrels in

individual study areas have had charging stations added to the desks. Library

staff installed a multi-device charging station in the library foyer, as well

as a monitor for streaming information content in the same area. A fleet of 20 laptops and 15 iPads are now

circulating to library users. Lastly, facilities replaced the old air

conditioning/heating system in the summer of 2016. The combination of increased

power access, increased network quality, better quality environmental control,

and additional technology shows substantial moves toward a more robust virtual

information commons.

Library staff created a

dedicated quiet study area complete with additional carpeting, indoor plants,

new artwork, individual carrels with lamps, and multi-port surge-protecting

power strips. Re-positioning of large tables to one end of the main floor, and

grouping smaller tables together on the other end allowed for some sense of

separate study spaces. This has been successful in reducing “social noise”

complaints. Two further areas have been designated “study lounges,” complete

with overstuffed chairs, lap-rest boards, and coffee tables. An improved

classroom was created with space made available by substantially reducing the

print journal collection, and has a wall-mounted smart board, modular

furniture, multiple mobile white boards, and a mobile smart board. This

dramatically improved instruction and collaboration in the library. These

changes are facilitating a cultural information commons at the Gellert Library.

A complete inventory of the

collection, with an orientation towards refurbishment, was finished in spring

2016. The inventory will help librarians and faculty work through a thorough

weeding process, making the physical collection more current, browsable, and

complete. The inventory project will also allow library staff to consider ways

to highlight the collection in the building, thus creating an environment such

as those described by patrons in the formal interviews. Lastly, dedicated group

study rooms (presently labeled a learning commons in the architectural

renderings) will be included in the coming renovation of the Ralston Manson, a

beautiful historic structure located on campus. The addition of some enclosed

study rooms, even if they are not in the library itself, will complete the list

of priority changes elicited via this research.

Conclusions

Students today do not require the services once demanded by previous

generations of library users. The present library building, designed to

facilitate individual, quiet, textual based learning, no longer serves the

needs of its patrons. Analysis of this project’s data supports the need to

develop quiet study spaces, to increase access to power outlets, and to develop

group study spaces. Patrons are satisfied with access to computers, librarians,

the library collection, and even to some extent the current building. When

asked to envision a new library building, respondents instead discussed

alterations to the present one. Many respondents described the value of the

building as a marker of community for users, especially for students living on

campus. Building a learning community was especially important to students as

they envisioned what a library “is.” Not only did students identify the library

as a place where knowledge is stored and accessed, as a place of active

learning, but also as a place of knowledge sharing between individuals. In

essence, they described an information commons.

Today,

most students at NDNU can access tremendous amounts of information using their

personal devices. Yet the role of the physical library on campus is even more

important than ever before. The Gellert Library is not just a place to store

books. Rather, it is a place where meaning and learning emerges from access to

knowledge. As the library continues its transformation into an information

commons, it has become a welcoming space that encourages exploration, creation,

and collaboration between students, teachers, and the broader community. We

hope that our library will continue to inspire users to construct new knowledge

and meaning.

References

Allison, D. (2015). Measuring the academic impact of libraries. Portal: Libraries and the Academy, 15(1), 29-40.

Asher, A., & Miller, S. (2010). So

you want to do anthropology in your library?: A practical guide to ethnographic

research in academic libraries. Illinois, The Ethnographic Research in

Illinois Academic Libraries (ERIAL) Project. Retrieved from http://www.erialproject.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/03/Toolkit-3.22.11.pdf

Beagle, D. (1999).

Conceptualizing an information commons. Journal of Academic Librarianship, 25(2), 82-89. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0099-1333(99)80003-2

Beagle, D. (2006). The information

commons handbook. New York: Neal-Schuman.

Beagle, D. (2011). From learning commons to learning outcomes. EDUCAUSE Center for Applied Research

Bulletin, Fall, 1-11. Retrieved from https://net.educause.edu/ir/library/pdf/ERB1114.pdf

Bennett, S. (2008). The information or the learning commons: Which will

we have? The Journal of Academic

Librarianship, 34(3), 183-185.

Bennett, S. (2009). Libraries and

learning: A history of paradigm change. Portal:

Libraries and the Academy, 9(2),

181-197.

Blum, S. D. (2009). My word! Plagiarism and college culture.

Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Bryant, J. (2007). An ethnographic

study of user behavior in Open3 at the Pilkington Library, Loughborough

University (Master’s dissertation). Retrieved from https://dspace.lboro.ac.uk/2134/3136

Bryant, J. (2009). What are students doing in our library? Ethnography

as a method of exploring library user behavior. Library & Information Research, 33(103), 3–9.

Delcore, H. D., Mullooly, J., & Scroggins, M. (2009). The library study at Fresno State. Fresno,

CA: Institute of Public Anthropology, California State University. Retrieved

from http://fresnostate.edu/socialsciences/anthropology/documents/ipa/TheLibraryStudy(DelcoreMulloolyScroggins).pdf

Duke, L. M., & Asher,

A. D. (Eds.). (2011). College libraries and student culture: What we

now know. Chicago: American

Library Association.

Foster, N. F., & Gibbons, S. (2005). Understanding faculty to

improve content recruitment for institutional repositories. D-Lib Magazine, 11(1). Retrieved from http://dlib.org/dlib/january05/foster/01foster.html

Foster, N. F., & Gibbons, S. (Eds.). (2007). Studying students: The undergraduate research project at the University

of Rochester. Chicago: Association of College and Research Libraries.

Head, A. J., & Eisenberg, M. B. (2009). Lessons learned: How college students seek information in the digital

age. Washington: Information School, University of Washington. Retrieved

from http://ctl.yale.edu/sites/default/files/basic-page-supplementary-materialsfiles/how_students_seek_information_in_the_digital_age.pdf

Heitsch, E. K., & Holley, R. P. (2011). The information and learning

commons: Some reflections. New Review of

Academic Librarianship, 17(1),

64-77. DOI:10.1080/13614533.2011.547416

Holland, B. (2015). 21st-century

libraries: The learning commons. Retrieved October 02, 2016, from http://www.edutopia.org/blog/21st-century-libraries-learning-commons-beth-holland

Jahn, N. (2008). Anthropological motivated usability evaluation: An

exploration of IREON – international relations and area studies gateway. Library Hi Tech, 26(4), 606–621. DOI 10.1108/07378830810920932

Khoo, M., Rozaklis, L., & Hall, C. (2012). A survey of the use of

ethnographic methods in the study of libraries and library users. Library

and Information Science Research, 34(2), 82-91. DOI:10.1016/j.lisr.2011.07.010

Moffatt, M. (1989). Coming of age in New Jersey: College and

American culture. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

Nathan, R. (2005). My freshman year: What a professor learned

by becoming a student. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Ostrander, M. (2008). Talking,

looking, flying, searching: Information seeking behavior in Second Life. Library Hi Tech, 26(4), 512–524. DOI 10.1108/07378830810920860

Othman, R. (2004). An applied ethnographic method for evaluating

retrieval features. Electronic Library,

22(5), 425–432.

Rawal, J. (2014). Libraries of the

future: Learning commons a case study of a state university in California (Master’s

thesis). Retrieved from http://hdl.handle.net/10211.3/134872

Sandstrom, A. R., & Sandstrom, P. E. (1995). The use and misuse of

anthropological methods in library and information science research. Library Quarterly, 65(2), 161-99.

Smale, M., & Regalado, M. (2010). Undergraduate scholarly habits ethnography project. Grace-Ellen McCrann Memorial Lecture, LACUNY

Spring Membership Meeting, CUNY Graduate Center, June 11, 2010.

Suarez, D. (2007). What students do when they study in the library:

Using ethnographic methods to observe student behavior. Electronic Journal of Academic and Special Librarianship, 8(3).

Retrieved from http://southernlibrarianship.icaap.org/content/v08n03/suarez_d01.html

Appendix A

Patron Recording Map

Staff used this map to record where patrons were sitting, if they were

using a laptop, and if they were studying individually or in groups.

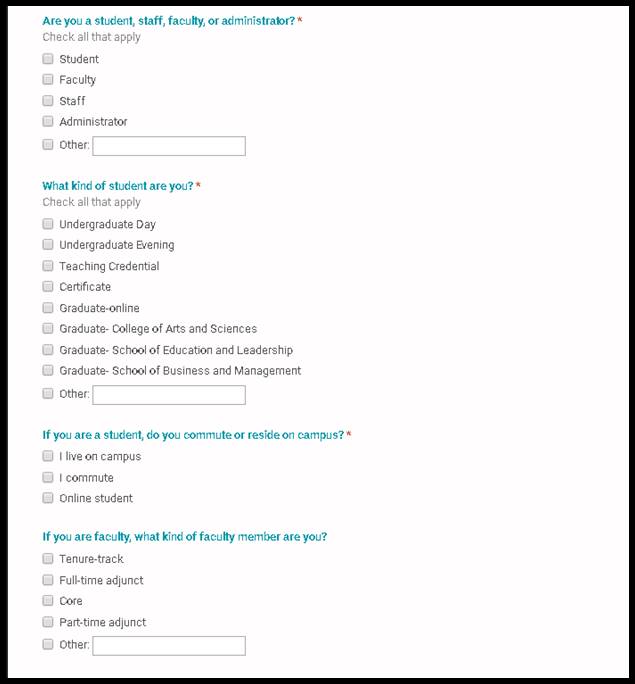

Appendix B

LIBRARY SURVEY

Staff used this survey to measure the frequency of use

and patron satisfaction with the library space and services.

Appendix C

Space Assessment Interview Guide

The project leader used

formal interviews to gain insight into who used the library and why, and to

gain an understanding of how users viewed the library building.

What academic year

are you?

Do you live on

campus or commute?

What days are you on

campus?

When you are on

campus, where do you study and why?

Where else is there

to study besides the library?

What is the ideal

setting for you when studying?

What kinds of

academic activities do you do when you are in the library?

When in the semester

do you use the library the most?

Why is there a

library on campus?

What do librarians

do?

Describe the

importance of having a library to you/your major

Have you gotten help

from library staff? Tell me about your experience…

Have you used the

paper book collection? Tell me why and how…

Do you use the

databases? Tell me why and how…

Do you use the

library website? Tell me why and how…

If you imagined the

perfect group study space, what would it look like?

If you imagined the

perfect individual study space, what would it look like?

When you see a

library with shelves of books, what does it make you think about and how does

it make you feel?

When you see a row

of computer terminals in a library, what does that make you think about and how

does that make you feel?

Have you ever been

in the library and not had access to a computer? What do you do?

What would your

ideal library look like?

What other uses

could the library fulfill?

Appendix D

Comment Board Prompts

Staff used comment boards

to give students a venue for providing suggestions and comments about issues

important to the research.

What would make the

library instruction space a better learning environment?

In a couple words,

describe the perfect individual study space

In a couple words,

describe the perfect group study space

What do you like

about the library space?

What would you like

to see different?

In a couple of

words, tell us all the reasons you use the library

What matters the

most to you about the library?