Research Article

Identifying and Classifying

User Typologies Within a United Kingdom Hospital Library Setting: A Case Study

Lynn Easton

Library Manager (South)

NHS Greater Glasgow and

Email: lynn.easton2@ggc.scot.nhs.uk

Scott Adam

Assistant Librarian

NHS Greater Glasgow and

Trish Durnan

Senior Library Assistant

NHS Greater Glasgow and

Maria Henderson Library,

Email: trish.durnan@ggc.scot.nhs.uk

Lorraine McLeod

Assistant Librarian

NHS Greater Glasgow and

Beatson West of

Email: lorraine.mcleod@ggc.scot.nhs.uk

Received: 18 Dec. 2015 Accepted:

22 Oct. 2016

![]() 2016 Easton, Adam, Durnan, and

McLeod.

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative

Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

2016 Easton, Adam, Durnan, and

McLeod.

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative

Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

Abstract

Objective – To

identify available health library user typology classifications and, if none

were suitable, to create our own classification system. This is to inform effective future library

user engagement and service development due to changes in working styles,

information sources and technology.

Methods – No

relevant existing user typology classification systems were identified;

therefore, we were required to create our own typology classification

system. The team used mixed methods

research, which included literature analysis, mass observation, visualization

tools, and anthropological research. In this

case study, we mapped data across eleven library sites within NHS Greater

Glasgow and Clyde Library Network, a United Kingdom (U.K.) hospital library

service.

Results –

The findings from each of the NHS Greater Glasgow and Clyde Library Network’s

eleven library sites resulted in six user typology categories: e-Ninjas, Social

Scholars, Peace Seekers, Classic Clickers, Page Turners and Knowledge Tappers.

Each physical library site has

different profiles for each user typology.

The predominant typology across the whole service is the e-Ninjas (28%)

with typology characteristics of being technically shrewd, IT literate and

agile – using the library space as a touch down base for learning and working.

Conclusions – We

identified six distinct user types who utilize hospital library services with

distinct attributes based on different combinations of library activity and

medium of information exchange. The

typologies are used to identify the proportional share and specific

requirements, within the library, of each user type to provide tailored

services and resources to meet their different needs.

Introduction

Several

factors contribute to different types of users accessing hospital library

services. Whilst some users continue to

utilize the library for what could be considered traditional reasons (book

borrowing and book based studying) changing work patterns and space

restrictions mean that U.K. hospital libraries are also being used for

non-traditional purposes (work, online study and leisure). In addition, different learning styles and

technological competencies mean that library users now prefer to access

information through a variety of media such as smart devices.

Health

and hospital libraries are unique within the library sector with a very

time-limited user base due to clinical demands.

The users are primarily busy clinicians and nurses who have patient care

responsibilities, who demand instant access to information and who have no

available workstations within their workplace (Thomas & Preston, 2016) A large proportion of our users can be

students or student doctors who appear to be using mobile technologies on the

wards (Chamberlain, Elcock & Puligari, 2015). To satisfy the demands of

these different users and engage with their current and future service needs, a

short-life working party was set up within the National Health Service Greater

Glasgow and Clyde (NHSGGC) Library Network.

Service provision within NHSGGC libraries has been based on assumptions

that professional role predicts style of library use e.g. busy nurses would

focus on paper textbooks rather than electronic resources, with no further

investigation to corroborate these assumptions.

However, more recent day-to-day anecdotal observations led us to suspect

that this was no longer the case and that library use is based on

characteristics other than professional role.

We

chose to investigate if any relevant user typology classification scheme already

existed that could be used, or adapted, by hospital libraries to identify the

distinct differing classes of user that we encounter. The definition of typology namely

“classification of human behaviour characteristics according to type”

(“Typology”, 2007) was used to focus our project.

From

the literature review, we identified that there are no existing typologies that

match our particular needs to classify our users. Existing typologies originating from other

sectors did not apply to our unique status as a provider of library services to

busy clinicians, nurses, students and student doctors. As a result of identifying this gap within

the research literature, we created a unique user typology classification scheme

specifically for NHSGGC hospital libraries, but that could be used by other

health and hospital libraries. We used mixed methods research to uncover

relevant typologies and explored methods of visualizing our results.

Literature

Review

To

gain a better understanding and knowledge of NHSGGC library users we undertook

a literature analysis, based on themes, to identify the literature. Within the thematic literature analysis we

looked for information on the following themes: changing library space and

environments, what typologies have been used before, physical typologies,

virtual or online typologies, health library specific typologies, methods of

identifying the typologies and recommendations for use from these typologies. The literature review identified that library

environments are changing and that one way to identify our users’ current

requirements is to place our users into a classification scheme. Following the analysis of the literature, we

excluded out-of-hours, virtual and non-users from our project as out of scope.

We

searched the following sources: EMBASE, Emerald, Health Management Online,

HMIC, LISTA, MEDLINE and PsycINFO, and online library catalogues: OLIB and

Shelcat for English language literature published since 2008. The major search terms included the

following: library*, knowledge, information, typolog*, behavio*, characterist*

and millennial* (Appendix One). We

kept up to date with any literature found during our project and added it into

our knowledge base.

Changing

Library Environments

Analyzing

the changing library environment is identified as a theme by Holder and Lange

(2014), Talvé (2011) and Todd (2009).

Holder and Lange (2014) state how they used mixed methods to identify

space use and user satisfaction in Canada.

They used observation, as a technique, eleven times and showed

individual versus group study preferences and how this fed into service

development within the library physical environment.

Talvé

(2011) plots the changing use of libraries across the decades and identifies

the future of the library environment in Australia. She identifies that “the more virtual we

become, the more we seek tactile, earthy, soft nesting spaces”. She notes that “people like to be with other

people in neutral spaces” and the library has a physical role in this. She goes on to suggest that libraries are

“places for collaboration” where library users gather together to solve issues

creatively.

Also

in Australia Todd (2009) identifies that different library areas suit different

types, for example “introverts” may prefer seating that faces into the wall and

“extroverts” may prefer wide open comfortable seating. She made use of surveys and observations and

discovered discrepancies between what students planned to do and what they

actually did. For example, 32% of

students planned to work on individual assignments, but under observation only

25% were observed doing this. This study

identified that using observation and surveys improved library

performance. The use of typologies in

this article led us to acknowledge that we required to audit our own users to

identify their use for library service development.

Libraries

are evolving, matching user learning styles to physical and virtual library

space. Our study acknowledged that we

needed a tool to measure the classification of library users within a U.K.

hospital library environment to inform suitable changes to the library

environment to match our users’ working styles, medium of exchange and

activities.

Library

Typologies

Several

general non-library specific typologies were identified by Greene and Myerson

(2011), who noted that the world is changing to become more focused on the

economy of knowledge. These typologies

were identified via ethnographic study, interview and visual tools around how

people used their office space. This

London study suggested several typology classifications including anchors and

connectors. Greene and Myerson noted

generational typologies such as Generation X, Millennials and Baby Boomers. These typologies have a 20-year age span

therefore we discounted these typologies as too broad for the purpose of our

study, e.g. Baby Boomers will be retired or nearing retirement.

Library

specific typologies were identified by Bilandzic and Foth (2013) and Zickuhr,

Purcell and Rainie (2014). Within a

wide-ranging study of American public libraries, Zickuhr et al. (2014)

identified typologies including “library lovers” and “distant admirers”. Bilandzic and Foth (2013) analyzed library

use within a learning context in Australia; using ethnographic techniques

several typologies were identified e.g. “learning freak Fred” and “what can I

do here Sophia”. These typologies are

close to what we were looking to identify within the NHSGGC library hospital context,

but were rejected early on because the library context within this paper did

not fit our own research context as it is from a “digital cultural centre”

context. Our literature review did not

identify any health library specific typologies.

We

therefore discarded the use of existing library typologies within our research

topic. The use of existing typologies

would have been time saving and would have created comparable results to study

within published papers. In reality we

did not feel that the typologies presented to us within the literature could be

transferred to the one situation with NHSGGC hospital libraries because our

study is aimed at classifying users within the physical use of space only, and

in a professional NHS health service hospital setting. We expected our small data sample size would

not cover more than two generations.

This meant that we rejected the use of known typologies due to the

differences in scale and limited transferability of results from our U.K.

hospital setting compared to the large-scale users and resources of public

library or higher education library settings.

Virtual

and Online Typologies

Virtual

or online typologies were identified by Lawrence and Weber (2012), Brandtzaeg

and Heim (2011) and Nicholas, Rowlands, Clark and Williams (2011). In a study in the United States of America,

Lawrence and Weber (2012), observed higher education students late at night -

and generated amusement from students about the “diligence” of the librarians

observing them out of hours. However,

this is in a higher education setting which would result in high footfall, particularly

at exam times, and would not be comparable to the NHS Greater and Glasgow out

of hours setting. Within NHSGGC

libraries there is out of hours use, particularly for on-call staff, rather

than students. This study also

concentrated more on use of the library and activities rather than typologies.

Brandtzaeg

and Heim (2011) from Norway identified online social networking typologies such

as “sporadics” and “lurkers” using an online questionnaire, whilst Nicholas et

al. (2011) identified web information seeking behaviour in the United Kingdom. They classified the behaviours into various

animal typologies such as “web hedgehog” and “web ostrich”.

Due

to the relatively low numbers of out of hours library users within the NHSGGC

context and the challenges of identifying virtual typologies, the typologies

identified in these papers were rejected as methods for our research. There is a noted potential to study these at

a future date if resources such as new technologies e.g. tracking via mobile

apps became cheaper and more widely available.

Typology

Methodologies

Typology

methodologies are discussed by Urquhart (2015), Kline (2013), Gajendragadkar et

al. (2013) and Lawrence and Weber (2012).

Observation can be a very useful research tool and Urquhart (2015) noted

that as yet “little research discussed observation as a major part of the

research methodology”, whilst suggesting that it can be a time and labour

intensive process. She notes that modern

digital tools such as “phones and digital recorders” make observation a

relatively easier method to use than in the past.

Kline

(2013) interviewed David Green from the ERIAL (Ethnographic Research in

Illinois Academic Libraries) project (ERIAL, 2015), and he confirms that even a

relatively tiny study can identify a lot about your library users. The negative side of this is that it can take

a great deal of staff time to run such a study.

He also identifies that using ethnography puts librarians into

the “users’ world” thus motivating change, and this matched the service

improvement goals of our project.

Gajendragadkar

et al. (2013) undertook a covert observational study in an NHS hospital setting

proving that such ethnographic techniques could be used within an NHS

setting. Similarly, Lawrence and Weber

(2012) noted that their research took in a variety of styles “written surveys,

interviews, observation, mapping and statistics” and this encouraged us to

proceed with mixed methods research within our own project.

Online

tools such as blogs and social media (#UKAnthrolib, 2014 and Lanclos, 2015) are

used to identify anthropological and ethnographic methods within library

settings and these tools informed our small-scale project.

Ethnography

has historically been linked to both anthropology and sociology. Reeves, Peller, Goldman and Kitto (2013) in

their paper on ethnography, within educational research, state that “the

ethnographer goes into the field to study a cultural group”. They also go on to note that small groups

have been studied and documented since the early twentieth century. Our study aimed to identify a small group,

namely U.K. hospital library users, and this fits in with the ethnographic

methodology.

Brewer

(2000) states “ethnography is not one particular method of data collection but

a style of research” and its ability to mix and match research methods such as

observation, personal diaries and interviews gives credence to the fact that

ethnography has become an evolving and increasingly used tool within libraries

within the last ten years as can be seen from the popularity of the UX (user

experience) in Libraries concept (UXLIBS, 2016).

Typologies

Use in Practice

The

literature also identified recommendations for how typology classifications

could be used. Bilandzic and Foth (2013)

suggest that new mobile device technologies allow a more fluid and non-owned

space. This resonated with our project

as this matches the increased number of agile workers using library space

within NHSGGC. Their research is not

directly replicable with our users as the observation took place over five

months within a large library and we were unable to devote similar timescales

to our project.

Difficulties

in finding out what non-users think and do in the library were identified in

the United Kingdom by Booth (2008). He

categorised people into typologies such as “non-seekers” or “confident

collectors”. He described how typologies

can help influence the design for library space around the various different

wants and demands of users. This

specifically fits in with the demands and requirements for service improvements

due to changes of working styles, technologies and information resources within

NHSGGC. We rejected this typology

because the research is not set in a U.K. hospital library setting.

We

identified that NHSGGC libraries have been evolving with the change of use both

traditionally and technologically and from solitary to group learning to

virtual. We identified that we need to

observe user typologies that, once diagnosed, can be used as a tool to develop

library services. We searched the

literature and identified that typologies have been classified within the

library and digital contexts but that the previous research did not drill down

specifically enough for the purposes of our research within the U.K. hospital

library context.

Methods

The

short life working group did not identify a relevant user typology

classification tool within the literature, suitable for a U.K. hospital library

setting, therefore we created our own typology classification system. The team used mixed methods research

including literature analysis, mass observation, visualization tools and

ethnographic research. We tabulated data

across eleven library sites within the NHSGGC Library Network.

Initial

scoping of Methods

Initial

discussions using Smart board® technology enabled the working group

to model, and have interactive discussions, around the definitions of users’

activities and how to collect the data.

Analysis

of the literature noted that mixed methods research methodology such as

observation is frequently used with typology work (Bilandzic & Foth,

2013). Observation includes the use of

qualitative and quantitative data. We

decided, using this evidence, to create an observational method that would suit

our small-scale library setting but that would be generic enough to be used in

any hospital library.

At

this stage, we devised an initial prototype three-dimensional activity axis

grid (Figure 1) based on our knowledge of NHS U.K. hospital libraries, and the

review of literature around changing library environments (Holder & Lange,

2014). We

came up with a three-dimensional cube, with gridlines, as we identified three

important dimensions of knowledge behaviour.

The

first dimension is the method of use, namely “traditional” use (e.g. reading a

book) or “virtual” (e.g. searching a database), giving the potential for

“mixed” use (e.g. reading a book whilst utilising a laptop). Our second dimension is whether the activity

is undertaken alone (solitary) or within a group.

The

third dimension is the activity itself within the library setting which, we

identified, could consist of study (e.g. reading a textbook), information

seeking (e.g. asking library staff for help with finding an electronic journal

article), or reflection/learning (e.g. writing up an audit).

Figure 1

Prototype three-dimensional activity axis grid.

Test

Observation

Observation

includes the use of qualitative (e.g. asking library users what space they use

within the library for what purpose) and quantitative data (e.g. numbers of

people sitting at a particular seat within the library over a given

period). Urquart (2015) defines this

type of observation as “simple observation” which enables you to watch what is

happening but not intervene or change the activity. We felt that simple observation would avoid

the need to request ethics approval, and cause less disruption to our end-users

as frequent interruptions to question them would have disrupted their library

activity and studies.

In

October 2013, the group tested an initial observational tool on five NHSGGC

library sites. One hundred individual

bits of test data were collected. After

collection, we discussed our methods and any problems that had arisen, such as

being unsure which box to tick for various activities. This test also identified that our data

collection did not capture the three-dimensional activity that we had sought to

identify with the help of our prototype three-dimensional activity axis grid

(Figure 1).

Using

these data we redesigned the observation sheets several times, utilising test

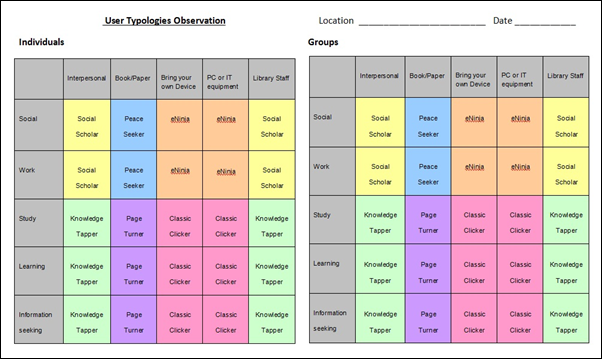

data, until we finalized our mass observation grid design (Figure 2).

Following

on from our prototype three-dimensional activity axis grid (Figure 1), we

refined the observation grid (Figure 2) into two separate grids each featuring

an axis of medium of information exchange versus an axis of library

activity. This created a two-dimensional

approach but across two separate facets of use, in theory the three axes we

originally worked to (Figure 1). The

first facet focused on solitary behaviour (individual people working alone) and

the second facet on groups (two or more people working together). This captured all the data we required but

created a more logical measurement.

We

defined the activities into learning, study, information seeking, working and

social (Figure 3). We also identified

and defined the resources utilized within the library space as interpersonal,

book/paper, bring your own device, PC/IT equipment and library staff.

Live

Mass Observation

The

live observation ran over one week in March 2014 on eleven sites within

NHSGGC. The observation took the form of

a paper grid (Figure 2), which was marked up by local library staff doing the

observation at each location. The

library sites varied from larger multi-disciplinary NHS libraries with large

footfall to smaller NHS libraries with part-time staffing and limited space.

Figure 2

Blank observation grid.

Figure 3

Observation grid guide.

Library

staff observed all use and footfall activity within the library setting – and

marked one score mark on the grid for every new activity versus medium of

activity. If users changed what they

were doing, or whom they were doing it with, this was noted on the grid as a

simple score. The record of activity

could be fluid e.g. one person could enter the library and take part in

different activities with different resources.

This did mean that the observation was open to a certain level of

subjectivity and therefore the working group offered an online WebEx®

conference to all library site staff to attempt to minimize potential

inconsistencies, and to explain the observation methods and techniques.

To

ensure consistency amongst all library sites participating in the live

observation we created an observation grid guide (Figure 3) that identified the

initial classification of users’ use of physical library space that we were

aiming to identify. These instructions

and examples of activities and resources formed the backbone of the

observation. This was backed up with the

working group acting as mentors during the week, who were able to intervene if

there were any questions whilst the observation was ongoing.

As

NHS library sites can be busy at different times, due to clinical requirements,

plus one library was moving location during this time, we were not prescriptive

about when sites would observe their users, just that they would observe within

the timeframe of that week. We also knew

that as sites are different sizes we would get different sample sizes from each

site. Therefore, we allowed library

sites the freedom to choose their sampling times and amounts, which in

retrospect may have affected our study sample size for some sites.

Visualization

Once

the data were returned from the eleven library sites, the working group

recorded, analyzed and tested the results of these data. The review of the literature had identified

that visualization of the data is the key to analyzing separate classes of data

(Urquhart, 2015).

We

analyzed the test data using Microsoft Excel® charts to enable

visualization. A promising output at

this stage was their surface contour charts.

Our initial thoughts were to produce some form of three-dimensional

visualization, as it was hoped that distinct typologies would jump out as peaks

or hot spots. The surface contour chart

(Figure 4) created the three-dimensional element we had used with our prototype

three-dimensional activity axis grid (Figure 1). Ultimately, this approach failed as the

imagery failed to produce the clear results for which we had hoped. Whilst the surface contour option (Figure 4)

enabled us to pinpoint accurately the specific cross sectional areas of high

activity of our library users, the contour chart did not provide a suitable

visualization of the axis between activity and resources that we were

seeking. The surface charts did help

towards us identifying the categorizations that we were interested in

establishing to enhance data analysis, at the intersections.

Figure 4

Surface contour map.

We

tested the Microsoft Visio® software package (Figure 5) which shows

an alternative visualization of the data.

This visualization software was rejected because it offered no relevant

graphical interpretation suitable for our needs as it did not show the axis of

information exchange versus an axis of library activity in enough detail.

Figure 5

Microsoft VISIO ® visualization.

We

re-analyzed the data and identified that to create typologies relevant to the

UK hospital library setting we needed to match the intersection of the observed

activity along one axis with the observed medium along the other. During this re-analysis it was identified

(Figure 6) that the chosen composite data of activity type (traditional or

non-traditional) intersecting with medium of information exchange (traditional,

technical or human) gave us the closest match to the number of user typologies

found in other papers e.g. Bilandzic and Foth (2013) and Brandtzaeg and Heim

(2011) who classified into five typologies.

Given the relatively small amount of data collected in our project, we

decided that six user typologies was the maximum number of classification types

into which the data could be split. We

therefore annotated our observational grid and mapped the data, where they

intersected, to our six typologies (Figure 7).

We

focused our typologies research on the medium of information exchange, plus the

actual library activity, rather than actual professional health service staff

or undergraduate students. We did this

to ensure that we captured actual activity of library users rather than

assuming that because you were e.g. a doctor that you would automatically have

the same user typology as all other doctors.

The same applied to us identifying and classifying use by undergraduate

students on placement, as from the literature (Nicholas et al., 2011), we had

already noted that not all users within the same generation used resources in

the same way e.g. we are aware in our day to day library role of undergraduate

students who prefer physical books and older doctors who prefer to use e-books

for their work. We were interested in

what our users used the library for, how this use is changing and not in who

they were professionally.

Results

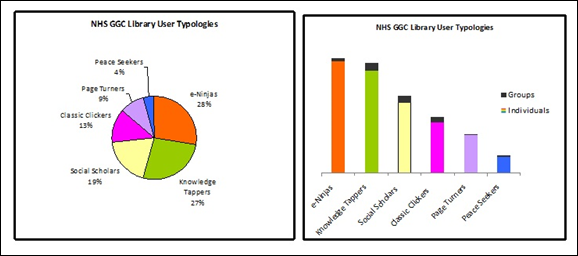

Collation

of the results of the two axes, firstly of traditional or non–traditional

activity intersecting with, secondly, traditional, technical or human medium of

information exchange led to the six user typology definitions: Page Turners,

Classic Clickers, Knowledge Tappers, Peace Seekers, e-Ninjas and Social

Scholars (Figure 6).

Individual

and group results were generated for each library site and for the NHSGGC

Library Network as a whole. We found

that user typologies were consistent across all eleven Library Network sites,

as we provide the same services to the same users, the only difference usually

being the size and scale of the library resources, library space and library

users on site. Overall results were

collated and e-Ninjas made up 28% of the individual user typologies identified

during this project (Figure 7).

Figure 6

User typology grid.

Figure 7

Mapping of observation grid data to user typologies

categories.

Figure 8

Mass observation results.

The

e-Ninja typology is most prevalent across the Library Network (28%) (Figure 8),

which reflects the move within NHSGGC organizational culture to agile

working. This type brings their own

device into the library and tends to be technologically competent. They use the library space as a buffer zone

between work and personal space.

The

second most popular typology, at 27%, is the Knowledge Tapper, who have

excellent interpersonal skills; they rely on knowledge from library staff and

can be seen as organizational knowledge brokers. The Knowledge Tapper requires a space to

communicate.

An

interesting typology, at 19% of those observed, are the Social Scholars, who

are also the typology most likely to operate in a group. This is due to their characteristics of being

more non-traditional users. They see the

library space as somewhere to learn from other people in a more informal manner

than previously seen within NHSGGC library space. They see the library as a third place.

A

steady number of users were identified as Classic Clickers (13%). This is the type of person who comes into the

library space just to use the PCs. They

use the PCs to learn and work, and use library staff for minor technical IT

issues. We felt that, over time, these

users may become e-Ninjas with encouragement.

Page

Turners were observed less frequently (at 9%) within the library space. This typology is traditional users, those who

come into the space and enjoy learning from books and paper. They come into the library to browse the

stock, will sometimes sit and study, but often take their books and papers to

their home or workplace.

The

lowest number of user typologies observed within the library setting is the

Peace Seeker, at just 4% of all observations, and this is a library user who is

looking for quiet and silence to work.

They are a solitary worker and see the library as a neutral space that

does not hold the distractions of work or home.

Peace Seekers need to concentrate and use the library as reflective

space.

Quick

Quiz

Once

we had identified our typologies, we wanted to test our hypothesis about how we

had classified library users. The

working group created a quick fun quiz using Questback (www.questback.com/uk)

to allow users to find out what typology they might be. We emailed out this link to Library Network

users and we got a return of over 350 user results. The results fundamentally differed from our

observation (Figure 9). The reasons for

this could include the fact that it was an online quiz and therefore attracted

a different typology. It may also mean

that virtual or online users, whom we did not capture in our physical library

observations, participated in the survey as it was emailed out to all Library

Network members. It may also have meant

our questions in the quiz needed recalibrating.

This is an interesting adjunct to the main research and allowed us to

question the validity of the main results of our research.

Figure 9

User typologies quiz results.

Discussion

Within

NHSGGC, each physical library site is shown to have different proportions and

profiles for each of our uniquely identified health library user

typologies. Although typology

methodologies were discovered in the literature review we felt that none of

these would fit the specific requirements of our project, e.g. web technology

typologies would not reflect our users’ physical footfall. We recognised through our observation that

users can have multiple typologies and that these can change over time.

Many

recent articles have focused more on virtual typologies, which we felt would be

hard to capture, within our NHSGGC context given our limited project

timescale. We also rejected Millennials

and Generation X style typologies at this stage, as they are wider generational

typologies and too broad for the purposes of this case study.

The

results of our typologies research in 2014 enabled us to forecast changing

typology use for a new library site that opened in 2015. Through utilizing the data from this project,

we identified that a new-build U.K. hospital library would require more space

for e-Ninjas and group learning types such as Social Scholars, than Page

Turners or Peace Seekers. We input this

research into the architect plans and enabled zoning more space for e-Ninjas

(agile, fluid laptop users) e.g. creating adaptable power points and Wi-Fi

across the library to enable rapid access to information. We required three separate rooms within the

library space, which are used flexibly to suit different typologies at

different times. One of the spaces is

bookable as a group space for e.g. Social Scholars, but when the room is not

booked it creates more individual silent study space for typologies such as the

Page Turners and Peace Seekers.

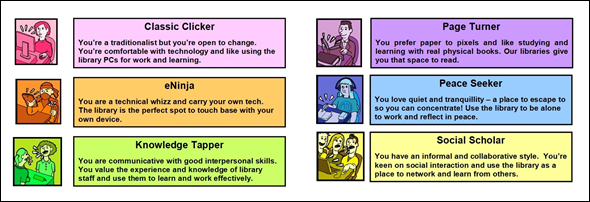

We

utilized the typologies as a promotional tool when this new U.K. hospital

library opened. We used six specially

designed bookmarks and posters (Figures 10 and 11), one for each typology, with

information about that specific typology and identified what library services

could be best suited to them. The

bookmarks grabbed attention and encouraged dialogue between library staff and

users.

Figure 10

User typology definitions for bookmarks.

Figure 11

Bookmarks and poster.

Future

Work

The

project took a lot longer to scope, plan and action than anticipated. The mass observation was run over one

week. There is potential to run it again

in the future to see if the proportions of typologies within the library

network change as library environments develop.

We

hope this study has added to the literature on user classification tools within

libraries. Informal feedback from other

health sector library staff has been positive.

They recognized these typologies within their own user base and

indicated that they are keen to use this classification system in their own

libraries. Ideas that could be explored

in the future, that were beyond the scope of this project, include the

potential to capture more closely multiple typologies of individuals or groups

over time. Virtual and out of hours

typologies were also beyond the scope of the current project but would be an

interesting project to pursue in the future.

Conclusions

Currently

there is a lack of studies relating specifically to user typologies within the

UK hospital library sector. Our case

study enabled us to create a bespoke user typology classification system that,

when used in conjunction with a programme of structured observation, could be

utilized by other U.K. hospital libraries to gain an understanding of how their

users utilize physical library services and space. Consequently, user engagement and service

development could be more effective as services, resources and physical design

will be based on health-specific user typologies.

References

#UKAnthrolib. (2014, Mar.). Spaces,

places and practices: UCL-IOE joint library anthropology seminar. Retrieved

from https://storify.com/senorcthulhu/spaces-places-and-practices-ucl-ioe-joint-library

Bilandzic, M., & Foth, M. (2013).

Libraries as coworking spaces: Understanding user motivations and perceived

barriers to social learning. Library Hi Tech, 31(2), 254-273. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/07378831311329040

Booth, A. (2008). In search of the

mythical "typical library user". Health Information and Libraries

Journal, 25(3), 233-236. https://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-1842.2008.00780.x

Brandtzaeg., P. B., & Heim, J.

(2011). A typology of social networking sites users. International Journal

of Web Based Communities, 7(1), 28-51. https://dx.doi.org/10.1504/IJWBC.2011.038124

Brewer, J. D. (2000). Ethnography.

Buckingham: Open University Press.

Chamberlain, D., Elcock, M., &

Puligari, P. (2015). The use of mobile technology in health libraries: A

summary of a UK-based survey. Health Information & Libraries Journal, 32(4),

265-275. https://dx.doi.org/10.1111/hir.12116

Ethnographic

Research in Illinois Academic Libraries. (2015). ERIAL project. Retrieved from http://www.erialproject.org/

Gajendragadkar, P.R., Moualed, D.J.,

Nicolson, P.L., Adjei, F.D., Cakebread, H.E., Duehmke, R.M., & Martin, C.A.

(2013). The survival time of

chocolates on hospital wards: Covert observational study. BMJ, 347, f7198. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmj.f7198

Greene, C., & Myerson, J. (2011).

Space for thought: Designing for knowledge workers. Facilities, 29(1/2),

19-30. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/02632771111101304

Holder, S., & Lange, J. (2014).

Looking and listening: A mixed-methods study of space use and user satisfaction.

Evidence Based Library and Information Practice, 9(3), 4-27. http://dx.doi.org/10.18438/B8303T

Kline, S. (2013). The librarian as

ethnographer: An interview with David Green. College & Research

Libraries News, 74(9),

488-491. http://crln.acrl.org/content/74/9/488.full

Lanclos, D. (2015). Donna Lanclos - the

anthropologist in the stacks. Retrieved from

http://www.donnalanclos.com/

Lawrence, P., & Weber, L. (2012). Midnight-2.00

a.m.: What goes on at the library?

New Library World, 113(11/12),

528-548. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/03074801211282911.

Nicholas, D., Rowlands, I., Clark, D.,

& Williams, P. (2011). Google generation II: Web behaviour

experiments with the BBC. Aslib Proceedings, 63(1), 28-45. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/00012531111103768

Reeves, S., Peller, J., Goldman, J.,

& Kitto, S. (2013). Ethnography in qualitative educational research: AMEE

guide no. 80. Medical Teacher, 35(8),

e1365-e1379. http://dx.doi.org/10.3109/0142159X.2013.804977

Talvé, A. (2011). Libraries as places of

invention. Library Management, 32(8/9), 493-504. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/01435121111187860

Thomas, G., & Preston, H. (2016).

Barriers to the use of the library service amongst clinical staff in an acute

hospital setting: An evaluation. Health Information & Libraries Journal,

33(2), 150-155. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/hir.12141

Todd, H. (2009). Library spaces - new

theatres of learning: A case study. Journal of the European Association for

Health Information and Libraries, 5(4), 6-12.

Typology. Shorter Oxford English

dictionary (6th ed.). (2007) Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Urquhart, C. (2015). Observation

research techniques. Journal of EAHIL, 11(3), 29-31. http://eahil.eu/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/29-31-Urquhart.pdf

UXLibs. (2016). Exploring ethnography,

usability and design in libraries. Retrieved from http://uxlib.org/

Zickuhr, K., Purcell, K., & Rainie,

L. (2014). From distant admirers to

library lovers - and beyond: A typology of public library engagement in America.

In Pew Research Center. Retrieved 6

Nov. 2016 from http://www.pewinternet.org/2014/03/13/library-engagement-typology/