Introduction

For years, academic librarians faced with

static or reduced collection budgets have searched for e-journal usage metrics

that would best inform difficult retention decisions. Download statistics do

not tell the whole story; an article download does not indicate whether it is

later read or cited. The cost-per-use figures derived from them rarely resonate

with faculty when it is “their” journal on the chopping block. Further, each

usage metric has unique limitations. Login data from OpenURL link resolvers

lose track of the user when the user reaches the publisher site, and thus may

not capture all of the eventual downloads. COUNTER-compliant download data is

not available from all publishers, especially small societies. Journal rankings

such as impact factor are based on a short time interval that does not

necessarily reflect the citation or publishing patterns of all disciplines.

Such rankings are also not available for many social sciences or arts and

humanities journals, and can be manipulated to some extent. Ideally, librarians

would like to connect available usage measures to research outcomes in a valid

and meaningful way.

The authors sought to compare the available

metrics and determine the value users assign to a collection through their

decisions about the journal articles they download and the journals they

publish in, as well as the value inherent in their peers’ decisions to cite

faculty journal articles.

Literature Review

The Centre for Information Behaviour and the

Evaluation of Research (CIBER) at University College London studied publishing

patterns of researchers in six disciplines at eight UK universities. They found

a strong positive correlation between the use of e-journals and successful

research performance. Institutions varied in use more than disciplines but they

discovered that the journals accounting for the top five percent of use could

vary by as much as 20% between the six disciplines (Jubb, Rowlands, &

Nicholas, 2010). Regardless of disciplinary and institutional variance,

electronic journal usage had positive outcomes.

An ongoing issue in collection analysis is

knowing which metrics to use to evaluate electronic journal usage and value.

The California Digital Library’s Weighted Value Algorithm (CDL-WVA) put into

practice the ideals underlying the results of their white paper (University of

California Libraries’ Collection Development Committee, 2007). Anderson (2011)

demonstrated a tool in which the selector can determine which publishers offer

the highest value for money to the academic department, and also how that

publisher’s demonstrated value changes on the value scale. This kind of

dashboard gives selectors a tool customized to their subject areas. Customized,

easily used tools such as this are increasingly important to ensure broad

adoption of metrics evaluations.

The University of Memphis adapted California

Digital Library’s journal value metrics and compared them with faculty

decisions on which journals to cancel. Knowlton, Sales, and Merriman (2014)

found that faculty selection of journals differed significantly from

bibliometric valuation, and that “higher CDL-WVA scores are highly associated

with faculty decisions to retain a title, but lower CDL-WVA scores are not

highly associated with decisions to cancel” (p. 35). To explain the difference,

they suggested that special faculty research needs, institutional pressure to

retain titles for accreditation, and a focus on teaching over research by

faculty all lead to certain journals selected for retention while not

frequently being downloaded or cited. These findings echo the authors’ findings

here in that the metrics valued by faculty are not always those used by

librarians.

Are metrics different when assessing

consortial package deals? Do limitations surface when assessing the value of

“big deals”? The Canadian Research Knowledge Network (CRKN) also adapted the

CDL approach. CRKN assessed whether the value of a consortial package of

journals stayed the same despite variation in institutional characteristics.

They found the top quartile was largely composed of the same journals,

regardless of the individual characteristics of the institutions. The overlap

of journal titles was around 90%. Similarly, the bottom quartile for each

school had an overlap of titles around 90%. Consortia could move from a big

deal to a smaller core package and still meet the needs of most members

(Jurczyk & Jacobs, 2014). Appavoo (2013) also found that when comparing

traditional cost-per-use against the CDL approach for the top 100 journals,

“The journal value metric method returned a wider variety of disciplines in the

results, while the use-based metric returned primarily journals in the STM

disciplines” (slide 11, notes). Schools using cost-per-use to reduce costs of journal

packages need to be careful not to disadvantage users in the social sciences

and humanities.

The Carolina Consortium also analyzed its big

deals, and found that the utility of cost-per-use metrics is mitigated by the

fluid nature of the industry (e.g., title changes, publisher mergers, etc.).

This should be just one of a suite of decision tools (Bucknall, Bernhardt,

& Johnson, 2014). This reinforces our findings that various metric analyses

must be employed for meaningful results.

Several studies document differences among

subject disciplines as to how closely download and citation behaviours are

related. The University of Mississippi examined publications by the business

school faculty to see what they cited. The conclusion was that local citation patterns

vary widely, even among departments in one discipline, thus necessitating

analysis at the local level (Dewland, 2011). Variations exist among

departments, let alone disciplines.

In the health sciences, a comparison of

vendor, link resolver, and local citation statistics revealed a high positive

correlation between the three data sets (De Groote, Blecic & Martin, 2013).

In another study, physicians from Norway examined the 50 most viewed articles

from five open access oncology journals, and concluded that more downloads do

not always lead to more citations (Neider, Dalhaug & Aandahl, 2013).

Fields in which faculty publish in

multidisciplinary journals, such as public administration and public policy,

provide additional challenges. In these cases, how are “good journals” defined?

The authors discuss measuring and ranking article output in the discipline and

the effect on analysis (Van de Walle & Van Delft, 2015). The complexity of

arrangements, e.g., single purchase electronic journals, big deal packages, and

interdisciplinary journals and fields, necessitate a more thorough approach and

point to a variety of metric analysis methods being more useful than a simple

cost-per-use model.

Another complicating factor for this endeavour

is open access. The University of Illinois at Chicago noted that a focus on

article downloads is indeed complicated by open access. Subject repositories

such as ArXiv, PubMed Central, RePEc, and SSRN can draw users without leaving a

COUNTER trail (Blecic, Wiberley, Fiscella, Bahnmaier-Blaszczak & Lowery.

2013), skewing analysis results. In the future, other metrics may become more

significant. A 2012 study sampled 24,331 articles published by the Public

Library of Science (PLoS) and tracked their appearance in tools such as Web of

Science citation counts, Mendeley saves, and HTML page views. As an indicator

of how open access is not only changing how researchers read and cite but how

they share articles, the authors found that 20% of the articles were both read

and cited, while 21% were read, saved, and shared (Priem, Piwowar, &

Hemminger, 2012).

The Pareto Principle is often mentioned in

journal usage studies. This is also known as the 80/20 rule, and states that,

for many events, roughly 80% of the effects come from 20% of the causes

(Nisonger, 2008). An example is a citation analysis of atmospheric science

faculty publications at Texas A&M University. It found 80% of cited journal

articles were from just 8% of the journal titles (Kimball, Stephens, Hubbard

& Pickett, 2013). Ten years earlier, one of the authors of this study and a

colleague found a larger percentage of titles, roughly 30%, comprising 80% of

downloads when analyzing use of all subjects in five large journal publishers

(Stemper & Jaguszewski, 2004). A small percentage of the total journals

were most heavily cited and downloaded in both instances. Taken together, one

could conclude that online journals lead users to read more but not necessarily

to cite more journals. The variety of metrics cited here reflect our findings

that collecting and correlating authorship and citation data allows patterns of

use to emerge, resulting in a more accurate picture of activity. The

development of more complex analysis will inform collection development in

meaningful ways in the future of academic libraries.

Aims

The authors had collected traditional link resolver and publisher

statistics for years, and to facilitate a study on e-journal metrics the

created a comprehensive “uber file”, one which combined all selected subjects

and publishers and allowed sorting by title or subject fund number. They

purchased and included a customized dataset from Thomson Reuters’ Web of

Science, the Local Journal Use Reports (LJUR), that showed which journals were

cited by University of Minnesota (U-MN) authors, the

journals in which they published, and which journal venues with U-MN authors

were cited by others. The authors felt they could no longer rely solely on

download statistics, which while convenient and comprehensive, are unfavourable

to disciplines that do not depend heavily on journal articles and are much more

favourable to disciplines that do, as shown in Table 1. Plus, as noted, there

was a wish to focus more on user outcomes, which made citation data attractive.

Table 1

Top Twenty Journals Accessed by University of Minnesota Students,

Staff and Faculty 20092012

|

Journal Title

|

Number of

Downloads

|

|

Science

|

44,114

|

|

Nature

|

39,407

|

|

Jama

|

33,126

|

|

The New England

Journal of Medicine

|

32,467

|

|

The Lancet

|

22,676

|

|

Harvard Business

Review

|

21,275

|

|

Journal of The

American Chemical Society

|

16,838

|

|

Proceedings of The

National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America

|

14,666

|

|

Pediatrics

|

12,485

|

|

Scientific American

|

12,213

|

|

Health Affairs

|

10,897

|

|

Annals of Internal

Medicine

|

10,757

|

|

Neurology

|

10,406

|

|

American Journal of

Public Health

|

8,937

|

|

Journal of Personality

And Social Psychology

|

8,515

|

|

Child Development

|

8,011

|

|

Critical Care Medicine

|

7,622

|

|

Ecology

|

7,534

|

|

Medicine And Science

In Sports And Exercise

|

7,263

|

|

Journal of Clinical

Oncology

|

7,153

|

The jumping-off point was an unpublished study by the Wendt

Engineering Library at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, a peer institution,

which surveyed faculty to gauge the importance of various criteria in journal cancellations.

The journals that engineering faculty cited the most in their articles were

ranked as most important, followed by journals that they published in, then in

decreasing order, usage statistics, impact factors, citation by peers, ending

with the metric of cost-per-use, the one most used by librarians (Helman,

2008). Due to perceived survey fatigue by U-MN faculty, a different approach

was developed using University of Wisconsin-Madison’s findings to guide the

investigation. The first phase of the authors’ investigation addressed U-MN

faculty’s citation patterns (Chew, Stemper, Lilyard, & Schoenborn, 2013).

This second phase addresses their choice of publication venue and external citations

to their articles in these journals.

Methods

The design of the study was heavily based on

the California Digital Library’s (CDL) Weighted Value Algorithm framework

project, which assesses user value in three overall categories:

1.

Utility:

usage statistics and citations

2.

Quality:

represented by impact factor and Source Normalized Impact Per Paper (SNIP)

3.

Cost

effectiveness: cost-per-use and the cost-per-SNIP

The weighted value algorithm combines these

aspects of use when assessing the journal’s value in the institutional context

while also factoring in disciplinary differences (Wilson & Li, 2012).

Adapting this approach, each journal’s value would be assessed by a) local

author decisions to publish there, b) external citations to institutional

authors, and c) cost effectiveness (via downloads and citations). In addition

to CDL’s categories of user-defined value-based metrics, data was added on U-MN

users’ departmental affiliations to assess any disciplinary differences. These

“affinity strings,” attached to a user’s resource login, are generated by U-MN

University’s Office of Information Technology with information from the

University’s human resources management system. All U-MN students, staff, and

faculty are assigned affinity strings that are based on his or her area of work

or study.

The study framed the following questions to

try to ascertain what faculty actually value with regards to the journal

collection:

1.

Utility

or reading value: Does locally-gathered OpenURL click data combined with

affinity string data provide a “good enough” departmental view of user

activities, such that COUNTER-compliant publisher download data is expendable?

2.

Quality

or citing value: Is Eigenfactor or SNIP an adequate substitute for impact

factor as a measure of faculty citation patterns?

3.

Cost

effectiveness or cost value: How should these reading and citing values be

combined with cost data to create a “cost-per-activity” metric that

meaningfully informs collection management decisions?

4.

Lastly,

to what extent could unique local usage data be leveraged: Do departments vary

greatly in their journal downloading, and do any of the measures predict which

journals U-MN faculty publish in and which of these articles will get cited by

their peers?

Table 2

Subjects Included in Study

|

Major Discipline

|

Department/School

|

Number of Subscribed

Titles

|

|

Arts & Humanities

|

History

|

48

|

|

|

|

|

|

Social Sciences

|

Accounting

|

14

|

|

Finance

|

22

|

|

Management

|

29

|

|

Marketing

|

15

|

|

Public Affairs

|

40

|

|

|

|

|

|

Physical Sciences

|

Chemistry

|

160

|

|

|

|

|

|

Life Sciences

|

Forestry

|

51

|

|

|

|

|

|

Health Sciences

|

Hematology

|

34

|

|

Pediatrics

|

64

|

|

Pharmacy

|

99

|

|

Nursing

|

115

|

The Data

The data for the project was collected from

nearly 700 e-journals that were licensed for system-wide use, owned by, or

accessible to the U-MN Libraries users. In order to discover whether or not

there may be any disciplinary differences in local faculty download or

authorship behaviours, or patterns of external citing by their peers, 12

subjects were chosen from four major disciplinary areas as defined by U-MN

Libraries’ organizational structure. In all but three cases, the authors were

either departmental liaisons or the previous subject coordinator. Table 2 lists

the subjects and the number of subscribed titles that were funded

for that subject. Subject relevant titles that were excluded from this project

included those that were part of consortia purchases or centrally-funded

full-text databases such as EBSCO’s Academic Search Premier, where resource

costs could not be parsed out to individual titles.

To gain an understanding into a journal’s

usage patterns, researchers used four years of usage data spanning from 2009

through 2012, along with 2-4 years of citation data, and journal impact metrics

from 2012. These were and analyzed by individual subject, and then combined in

a single spreadsheet for comparative analysis. The data variables collected,

sorted into CDL-WVA categories, are shown in Table 3.

The median figures were calculated for each

metric in order to reduce the influence of outlier results, except for impact

factor where 5-year scores that were available for the project titles were

used. Data could not be collected for all of the variables for every title, as

not every publisher is COUNTER-compliant, nor are there impact factor,

Eigenfactor, LJUR, or SNIP data available for every title. For the sciences

(with the exception of nursing) at least three-quarters of the titles had

journal ranking metrics available; Eigenfactor scores were available for 84-94%

of the titles, SNIP scores for 92-100% and impact factor for 78-94% of the

titles, where the 5-year impact factor was the least available. The difference

was only significant in nursing, where the gap was counted across 13 titles.

Conversely, the social sciences had a much lower comparative journal ranking

metrics. Eigenfactor scores were available for only 36-64% of the titles and

impact factor for 31-55% of the titles. On the other hand, the social sciences

did well with SNIP, ranging from 70-95% of the titles available (Table 4).

Table 3

E-Journal Metrics Collected

|

CDL-WVA Category

|

Metric

|

Years

|

|

Utility: Usage

|

Article view requests, as reported by the library’s OpenLink Resolver

SFX

|

2009-2012

|

|

Utility: Usage

|

Article

Downloads, as reported by publisher COUNTER- compliant reports

|

2009-2012

|

|

Utility: Citation

|

University of Minnesota a) authorship and b) citations to these

locally authored articles, from Thomson Reuter’s Local Journal Use Reports

(LJUR)

|

2009-2010

|

|

Utility: Citation

|

University

of Minnesota a) authorship and b) citations to these locally authored

articles, Elsevier’s SciVal/Scopus (2009-2012)

|

2009-2012

|

|

Quality

|

● Journal Citation Reports (JCR) Five Year Impact Factor (IF)

● Eigenfactor Scores

● Elsevier’s Source Normalized Impact per Paper (SNIP)

|

2012

|

|

Cost Effectiveness

|

●

Via Cost Per Download

●

Via Cost Per Ranking

(EBSCO

subscription price divided by SFX /COUNTER and Impact Factor/Eigenfactor/SNIP

as appropriate for each subject)

|

2013

|

Note. Due to the

significant yearly cost of a purchase of the LJUR dataset only the 2009-2010

dataset was available. Elsevier’s SciVal is an institutional level research

tool that provides a snapshot of institutional research performance at the

institutional and departmental level. Information provided by SciVal is drawn

from the Scopus dataset.

A Pearson’s correlation analysis was chosen to

examine if there was any relationship, positive or negative, between selected

journal metrics, whether or not there were any disciplinary differences between

the various metrics, and the potential significance or strength of those

relationships. The goal was to find which correlations, and thus which metrics,

provided the best “goodness of fit,” i.e., which best explained past patron use

of e-journals as well as best predicted their future use.

Data analysis was done using Excel’s CORREL

function. In conjunction with the correlation coefficient, “r”, the coefficient

of determination, which is the square of r and is reported as r-squared, was

calculated. All of the correlations’ F-test p-values were less than 2.2e-16 (2

x 10-16), therefore statistically significant. R-squared is often expressed as

a percentage when discussing the proportion variance explained by the

correlation. Though there can be a range of interpretation depending on the

discipline, it is generally accepted that within the social sciences, or when

looking at correlations based on human behaviour, an r<0.3 is considered a

low or weak correlation, 0.3-0.5 modest or moderate, 0.5-1.0 strong or high

correlations, with anything over 0.90 a very high correlation (Table 5), and R2

values anywhere between 30-50% are considered meaningful (Meyer, et. al.,

2001). A wide variety of correlations were run to provide comparison data

points.

Table 4

Percentage of Subscribed Journal Titles That

Have Impact Factors, Eigenfactors or SNIP

|

Department / School

|

No. of subscribed titles

|

% 5-year impact factor

|

% Eigenfactor

|

% SNIP

|

|

Hematology

|

34

|

94%

|

94%

|

100%

|

|

Pharmacy

|

99

|

91%

|

92%

|

95%

|

|

Pediatrics

|

64

|

80%

|

86%

|

92%

|

|

Nursing

|

115

|

44%

|

56%

|

86%

|

|

Chemistry

|

160

|

91%

|

91%

|

94%

|

|

Forestry

|

51

|

78%

|

84%

|

96%

|

|

History

|

48

|

31%

|

38%

|

83%

|

|

Marketing

|

15

|

40%

|

53%

|

80%

|

|

Management

|

29

|

55%

|

55%

|

93%

|

|

Finance

|

22

|

45%

|

64%

|

95%

|

|

Accounting

|

14

|

36%

|

36%

|

93%

|

|

Public

Affairs

|

40

|

55%

|

60%

|

70%

|

Table 5

Range of Pearson Values for Study

|

Correlation

|

Negative

|

Positive

|

|

None

|

-0.09 to 0.00

|

0.0 to 0.09

|

|

Low or Weak

|

-0.3

to -0.1

|

0.1

to 0.3

|

|

Moderate or Modest

|

-0.5 to -0.3

|

0.3 to 0.5

|

|

Strong

|

-1.0

to -0.5

|

0.5

to 1.0

|

Table 6

Comparison of Indexing of Locally-Held Titles in Web of Science and

Scopus

|

Department / School

|

No. of subscribed titles

|

No. of titles indexed in Scopus

|

% of titles indexed in Scopus

|

No. of titles indexed in Web of Science

|

% of titles indexed in Web of Science

|

|

Nursing

|

115

|

111

|

97%

|

54

|

47%

|

|

Pharmacy

|

99

|

98

|

99%

|

92

|

93%

|

|

Pediatrics

|

64

|

64

|

100%

|

56

|

86%

|

|

Hematology

|

34

|

34

|

100%

|

31

|

91%

|

|

Chemistry

|

160

|

156

|

98%

|

154

|

96%

|

|

Forestry

|

51

|

49

|

96%

|

49

|

96%

|

|

History

|

48

|

44

|

92%

|

41

|

85%

|

|

Finance

|

22

|

19

|

86%

|

13

|

59%

|

|

Accounting

|

14

|

13

|

93%

|

4

|

29%

|

|

Public

Affairs

|

40

|

31

|

78%

|

22

|

55%

|

|

Marketing

|

15

|

13

|

87%

|

5

|

33%

|

|

Management

|

29

|

28

|

97%

|

17

|

59%

|

Table 7

Comparison of Citing of U of M Authors in

Locally-Held Titles in Web of Science and Scopus

|

Department / School

|

No. of subscribed titles

|

Scopus:

U of M authors cited

|

% of titles cited in Scopus

|

Web of Science:

U of M authors cited

|

% of titles cited in

Web of Science

|

|

Nursing

|

115

|

26

|

23%

|

66

|

57%

|

|

Pharmacy

|

99

|

71

|

72%

|

94

|

95%

|

|

Pediatrics

|

64

|

45

|

69%

|

55

|

85%

|

|

Hematology

|

34

|

21

|

62%

|

33

|

97%

|

|

Chemistry

|

160

|

87

|

54%

|

144

|

90%

|

|

Forestry

|

51

|

22

|

43%

|

43

|

84%

|

|

History

|

48

|

4

|

8%

|

23

|

48%

|

|

Finance

|

22

|

7

|

32%

|

15

|

68%

|

|

Accounting

|

14

|

3

|

21%

|

4

|

29%

|

|

Public

Affairs

|

40

|

15

|

38%

|

23

|

58%

|

|

Marketing

|

15

|

6

|

40%

|

7

|

47%

|

|

Management

|

29

|

8

|

28%

|

21

|

72%

|

In order to determine “utility”, SFX link

resolver and COUNTER data were correlated with both the LJUR for local

authorship and local citing patterns and SciVal/Scopus data for local

authorship and local citing patterns. For “quality”, LJUR authoring/citing and

SciVal/Scopus authoring/citing data were correlated with impact factors,

Eigenfactors, and SNIP. The R² values that resulted from the correlations were

then inserted into bar charts for subject comparisons.

Indexing Selections by Publishers.

The two primary indexes used as a basis for

the “utility” and “quality” analysis, Web of Science and Scopus, were also

analyzed. The question was whether Web of Science or Scopus fared better in

tracking the publishing activity of U-MN faculty. The surprising discovery was

that neither Scopus nor Web of Science could function as a single data source

(Harzing, 2010). In answering the question of which database was the better

metric data source, it turned out that Scopus provided better authoring data,

because it indexed more of U-MN subscribed titles than Web of Science, ranging

from a low of

78% for public affairs titles to a high of

100% of pediatrics titles, compared to Web of Science, with a low of 47% for

nursing titles to a high of 95% for chemistry titles (Table 6). On the other

hand, Web of Science provided better citing data, because it contains citation

data dating back to the 1900s and includes citation data from journals that

they do not regularly index, whereas the majority of Scopus citing data only

goes back to 1996 and only includes titles that they index. Web of Science

ranged from a low of 29% for accounting titles to a high of 97% for hematology

titles, compared to Scopus, with a very low 8% for history titles and a modest

highest 72% for pharmacy titles (Table 7).

Results

Authorship Decisions by U of Minnesota

Authors, or, “Where do I publish my article?”

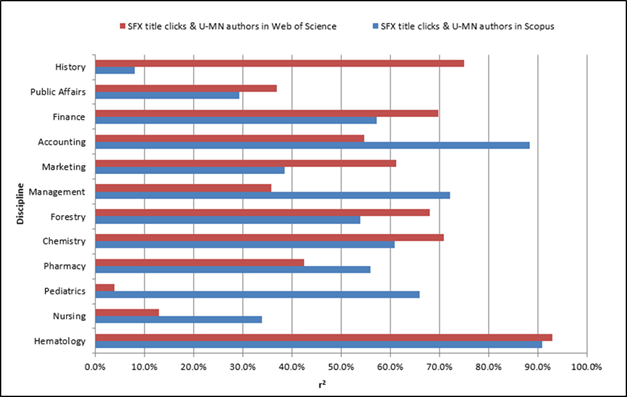

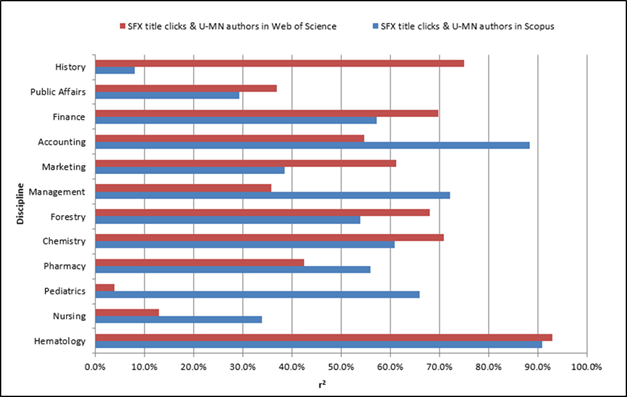

The

first question to answer was whether the journals in which U-MN faculty choose

to publish are also the journals that are most downloaded by U-MN users.

Overall, the social sciences and humanities had several moderate to strong

positive correlations between downloads and where faculty chose to publish.

Journals for Finance and Accounting were found to have a strong relationship in

both Web of Science and Scopus. History shows the greatest variation between

downloads and choice of authoring venue, with Web of Science at about 75%,

compared to Scopus at 8% predictive (see Figure 1). Pediatrics shows the

greatest variation in the Health Sciences between downloads and choice of

authoring venue, with Scopus at about 65% and Web of Science at about 5%

predictive.

Figure 1

Downloads and authorship choice based on SFX

title clicks correlated with U-MN authors titles in Web of Science or Scopus.

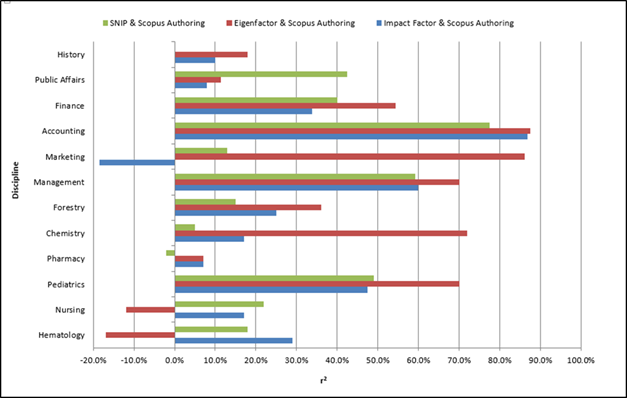

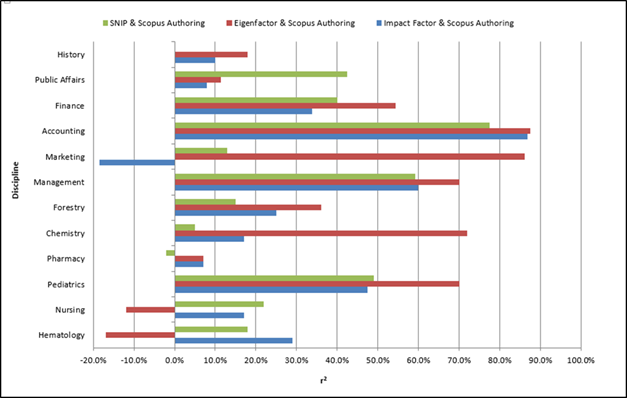

The next question to answer was whether the

journals in which U-MN faculty chose to publish are also the journals that

external rating services consider being of the highest quality. Using Scopus

authoring, Figure 2 illustrates initial results. In the Social Sciences and

Humanities subjects, the data show that no one impact measure stood out as most

predictive overall. Accounting and Management both show strong correlations for

all three measures, while, interestingly, a weak negative relationship was

found for Marketing.

In the Physical and Health Sciences, multiple

weak or negative relationships are evident. The negative correlations, while

low, may suggest there is close to no correlation between those journals that

faculty in Nursing, Hematology and Pharmacy chose to publish in and their value

rankings. On the other hand, in Pediatrics all of the value metrics

correlations are either moderate or strong, suggesting that impact factors or

similar value measures may play a role in faculty publishing decisions.

Figure 2

Journal ranking and authorship choice using

SNIP, Eigenfactor, and impact factor score correlated with U-MN authored titles

in Scopus.

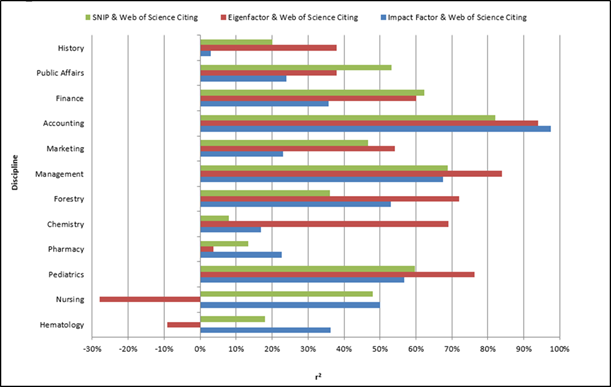

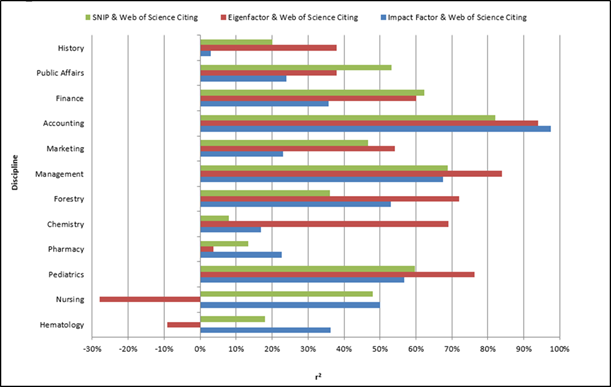

Comparatively, in the Web of Science authoring

results shown in Figure 3, the Social Sciences and Humanities impact factor

rankings overall were weak to moderate predictors, except for History where

impact factor is a strong predictor. Eigenfactor on the other hand, was the

overall stronger predictor, in the subjects of History, Finance, Accounting,

and very strong in Marketing.

Finally, SNIP proved to be a better predictor

only for Finance.

The Web of Science authoring results in the

Physical and Health Sciences subjects illustrate a very different, far less

stable pattern of correlations. Here Eigenfactor is most predictive only for

Chemistry, and all other Web of Science authoring relationships are moderate at

best, but mostly weak or negative.

In summary, the data comparing a discipline’s

impact measure and its faculty journal authoring choices suggests that impact

factor rankings are weak predictors about half the time, but the strongest

predictors are in the Humanities and Social Sciences where Eigenfactor may be

“good enough”.

Citing Decisions by Peers: Is this U-MN

article worth citing?

How are U-MN faculty researchers viewed by

their peers? To put it another way, were the journals that cited U-MN faculty’s

research also the most downloaded journals by U-MN users? Among the disciplines

analyzed, the external citing patterns for many disciplines, including Public

Affairs, Accounting, Finance, Management, Hematology, Pediatrics, Forestry,

Chemistry all showed strong relationships with either Scopus or Web of Science,

and as noted in Figure 4, a few instances of disciplinary relationship strength

in both tools. Conversely, History, Marketing, and Pharmacy had

weak-to-moderate citing correlations in both Web of Science and Scopus. Finally,

nursing results show the greatest variability, where Web of Science is strong

and Scopus is a negative relationship. The results show Web of Science citing

correlated stronger in the majority of disciplines except for Hematology,

Pediatrics, and Accounting, fields where Scopus is a stronger predictor.

Figure 3

Journal ranking and authorship choice using

SNIP, Eigenfactor, and impact factor score correlated with U-MN authored titles

in Web of Science.

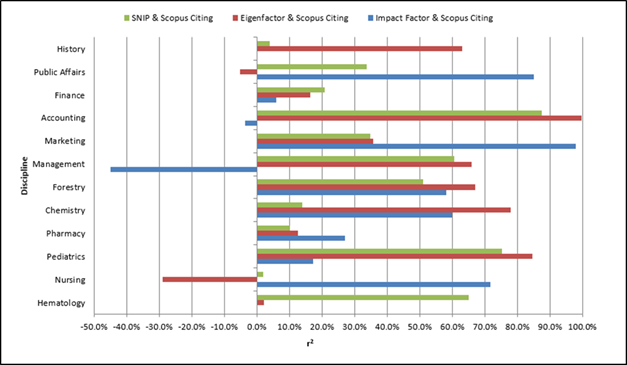

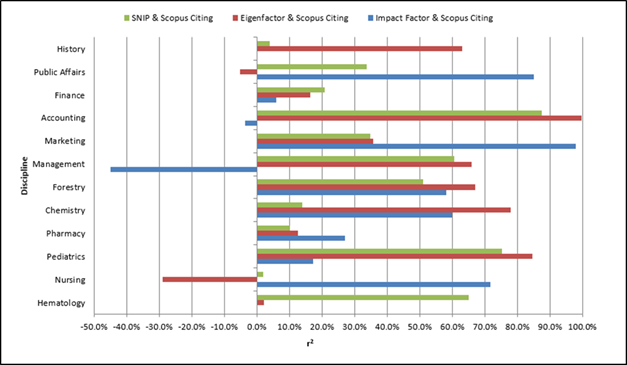

Also analyzed were citing decisions by

external authors and impact measures in Web of Science. Were the journals that

cited U-MN faculty’s research also the journals that external rating services

consider to be of the highest quality? As Figure 5 illustrates, the Social

Sciences and Humanities results present multiple strong correlations in

Management, Accounting, and Finance. Public Affairs and Marketing each have one

strongly predictive value measure, SNIP and Eigenfactor respectively. Overall,

the value metrics that are most predictive are SNIP and Eigenfactor.

In the Natural, Physical, and Health Sciences,

common patterns are far less pronounced, though for Forestry, Chemistry, and

Pediatrics, Eigenfactor is strongest. Beyond these subjects, Web of Science

citing shows moderate, weak or negative relationships to the three impact value

metrics.

Figure 4

Downloads and others citing U-MN based on SFX

title clicks correlated with cites to U-MN authored titles in Web of Science or

Scopus.

Figure 5

SNIP, Eigenfactor, and impact factor scores

correlated with cites to U-MN authors titles in Web of Science.

Figure 6

SNIP, Eigenfactor, and impact factor score

correlated with cites to U-MN authored titles in Scopus.

Using Scopus citing data, almost all

disciplines have at least one impact measure with strong correlation, but no

one measure stands out as most predictive overall. Figure 6 shows multiple

negative or weak relationships are evident when looking at peer citing

decisions in Finance, Pharmacy, and Nursing. And some of the strongest

relationships are found with impact factor for both Public Affairs and

Marketing. On the other hand, Eigenfactor is strongly predictive with peer citing

in History, Accounting, Management, Forestry, Chemistry, and Pediatrics.

Meanwhile, SNIP shows strong relationships in Hematology, Pediatrics,

Management, and Accounting.

Finally, these results provide evidence to

answer the question of comparative impact measure at the journal discipline

level. While many disciplines have multiple strong correlations, many also have

weak or negative relationships. Thus, discipline does matter in terms of

overall impact measure decisions, though patterns do emerge for some fields

where the discipline result may be sufficient for a group of subjects, such as

business, as we found for Eigenfactor in Web of Science. The same though cannot

be said for health subjects where a far more nuanced approach may be required.

Discipline Usage Behaviour

What could be the possible explanation behind

low to barely moderate, or even the negative correlations with regards to

authorship, citing behaviour, or relationships with value metrics such as

impact factor? Is there something in the usage behaviour of discipline specific

users that can provide insight? One way to understand these differences is to

look at U-MN’s affinity string data. Affinity strings provide some insight into

usage patterns at college or school level, as well as degree or subject

discipline level. Affinity string data reveals who is accessing U-MN electronic

resources without identifying a specific person.

Table 8

Affinity String Usage of Harvard Business Review 2009-2012

|

Affinity String

|

Status

|

College

|

Department /School

|

No. logins 2009-2012

|

|

tc.grad.csom.bus_adm.EMBA

|

Graduate

student

|

Carlson

School of Management

|

Business

Admin

|

2734

|

|

tc.grad.gs.humrsrc_ir.ma

|

Graduate

student

|

Graduate

School

|

Human

Resource Development

|

507

|

|

tc.grad.gs.

|

Graduate

student

|

Graduate

School

|

General

|

485

|

|

ahc.pubh.hcadm.mha

|

Graduate

student

|

Academic

Health Center

|

Public

Health

|

338

|

|

tc.grad.csom.bus_adm.DMBA

|

Graduate

student

|

Carlson

School of Management

|

Business

Admin

|

323

|

|

ahc.grad.nurs.d_n_p

|

Graduate

student

|

Academic

Health Center

|

Nursing

|

212

|

|

tc.grad.cehd.humrsrcdev.m_ed

|

Graduate

student

|

Education

& Human Develop

|

Human

Resource Development

|

156

|

|

tc.grad.csom.humrsrc_ir.ma

|

Graduate

student

|

Carlson

School of Management

|

Human

Resources

|

156

|

|

tc.grad.gs.strat_comm.ma

|

Graduate

student

|

Graduate

School

|

Strategic

Communication

|

133

|

|

tc.grad.gs.workhumres.phd

|

Graduate

student

|

Graduate

School

|

Work

& Human Resources Education

|

106

|

|

ahc.staff.pubh

|

Staff

|

Academic

Health Center

|

Public

Health

|

93

|

|

tc.grad.cehd.humresdev.humresd_gr

|

Graduate

student

|

Education

& Human Develop

|

Human

Resource Development

|

93

|

|

tc.grad.gs.mgmt_tech.ms_m_t

|

Graduate

student

|

Graduate

School

|

Management

of Technology

|

87

|

|

tc.ugrd.csom.mktg.bs_b.cl2011

|

Undergraduate

student

|

Carlson

School of Management

|

Marketing

|

86

|

|

tc.ugrd.fans.env_scienc.bs.nas

|

Undergraduate

student

|

Food,

Agricultural & Natural Resource Sciences

|

Environmental

Sciences

|

84

|

|

ahc.staff.med

|

Staff

|

Academic

Health Center

|

Medicine

|

81

|

|

tc.grad.gs.humrsrcdev.m_ed

|

Graduate

student

|

Graduate

School

|

Human

Resource Development

|

81

|

|

tc.grad.csom.bus_adm.CEMBA

|

Graduate

student

|

Carlson

School of Management

|

Business

Admin

|

73

|

|

tc.grad.gs.publ_pol.m_p_p

|

Graduate

student

|

Graduate

School

|

Public

Policy

|

57

|

|

tc.grad.cehd.workhumres.phd

|

Graduate

student

|

Education

& Human Develop

|

Work

& Human Resources Education

|

57

|

Sometimes this data reveals rather surprising

things. For instance, Table 8 shows that among the top twenty users of the Harvard Business Review are graduate

school nursing students, as well as public health and medical school staff. So

decisions about the Harvard Business

Review would not only impact the academic business community, but the

health sciences as well.

Figure 7

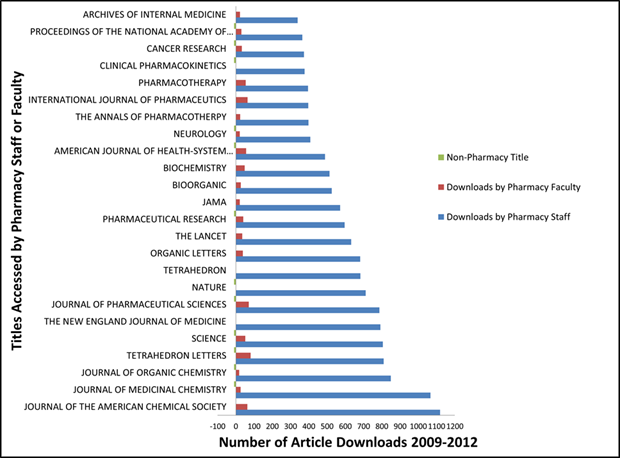

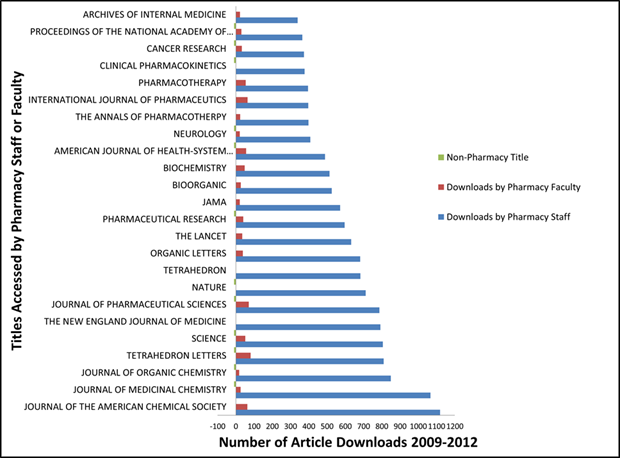

Nursing staff download activity versus nursing

faculty download activity

Figure 8

Pharmacy staff download activity versus

pharmacy faculty download activity.

Within a particular school, there can be

differences in what e-journals are accessed. Nursing or Pharmacy staff and

faculty (which includes research assistants, fellows, and PhD candidates)

access a wide variety of journals outside of their immediate disciplines.

Research staff download to a much greater extent than faculty, possibly because

they are the ones doing the bulk of the background work for grants,

publications, or curriculum instruction (Figures 7 & 8). So decisions about

any health sciences/bio-sciences titles could impact how the nursing school or

college of pharmacy would be able to conduct research, apply for grants, or

build curriculum content.

Publication Practices

When looking at where nursing or pharmacy

authors chose to publish, the vast majority publish within their disciplinary

journals. However, when looking through a list of articles that have the

highest citation counts that include nursing or pharmacy authors, the top

journals are not nursing or pharmacy journals, but well-known medical titles,

such as the New England Journal of

Medicine or Circulation.

Examining the author list from these articles reveals the increasing

interdisciplinary nature of research, where the nursing or pharmacy author is

one member of a team.

Selected Disciplinary Evidence: Visualizing

the Data at the Discipline Level

The results illustrate that disciplinary

trends exist. Can a more careful look at specific funds determine how these

data actually may impact librarian selection decisions, or certainly the

discussions that surround selection/deselection? To draw out patterns in the

data, and hopefully tease out a more meaningful story, the data was visualized

using Tableau software.

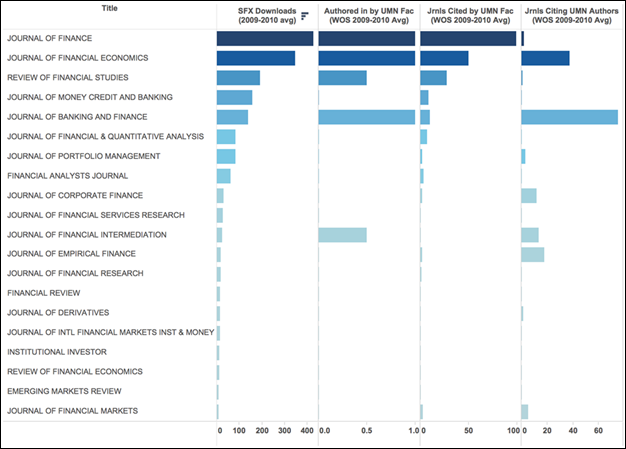

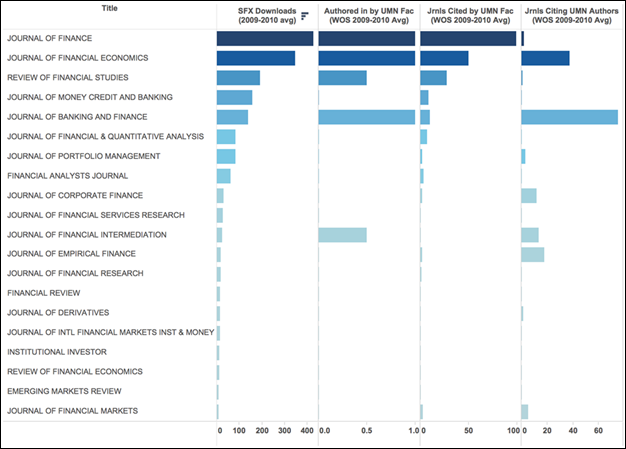

Figure 9

Journals selected using the Finance fund.

Figure 9 represents titles selected using the

Finance fund. As noted above, Web of Science was found to be a strong predictor

for both authoring in and peer citing for this subject. The addition of the

Authoring data shows Journal of Banking

& Finance and Journal of

Financial Intermediation as titles with comparatively few downloads but

marked faculty authoring activity. Couple this with the additional peer citing

data from the last column and it becomes clear that the Journal of Empirical Finance, Journal of Financial Markets, and the Journal of Financial Intermediation are titles with higher local

impact to U-MN faculty than downloads alone would suggest.

Figure 10 highlights titles selected using the

Public Affairs Fund. Seen here are International

Public Management and Journal of

Transport Geography as titles with a lower level of downloads, but marked

authoring and peer citing activity. These additional journal level views

provide a richer set of data from which to analyze collections.

Figure 10

Journals selected using the Public Affairs

fund.

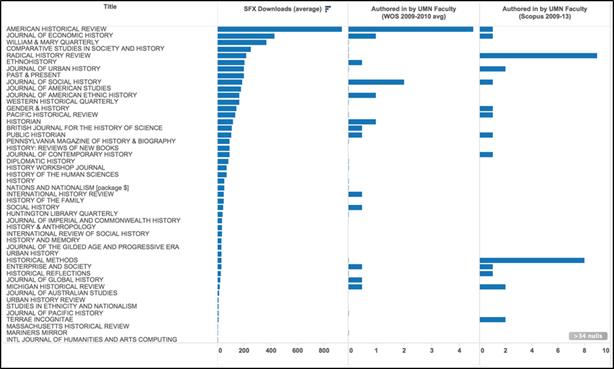

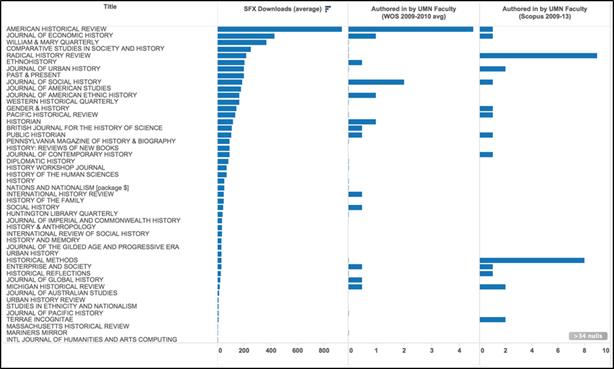

It is enlightening to consider how “weak”

“moderate” and “strong” correlations play out in practice. Through comparison,

the next couple of figures offer some insight. For example, data for authorship

and downloads in History are presented in Figure 11 because of the previously

noted gap between Web of Science authoring (at 75% correlation), shown in the

first column, and Scopus authoring (at only 8%) shown in the second column.

Comparing the LJUR and Scopus columns for

journals where data exists for both, Web of Science results are often higher

than Scopus, but not always. Noticeable outliers include Radical History Review and Historical

Methods with stronger Scopus authorship.

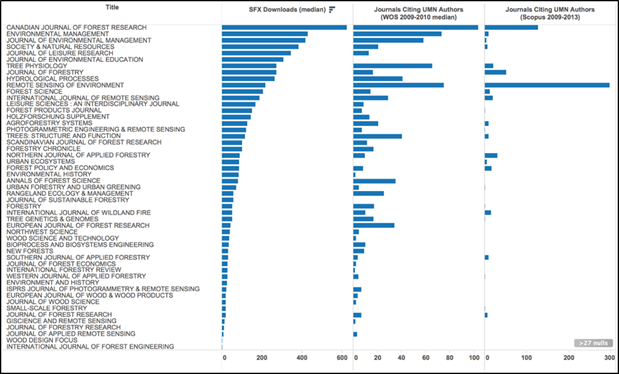

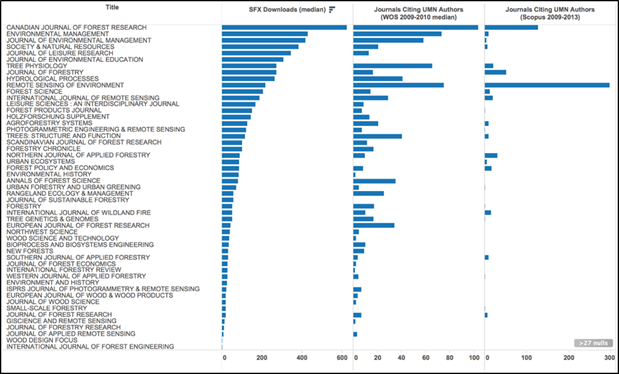

Forestry presents another view of variability

(Figure 12). Presented are downloads in relation to citing by peers of U-MN

authored works. The findings show Web of Science is the better predictor at 75%

to Scopus ‘moderate 35%.

While many of the same journals are

represented as having been cited by peers based on data for both Web of Science

and Scopus, what is remarkable is the degree of variation. Certainly, Web of

Science tells a strong story. Scopus tells a story too, just not as compelling.

The final case study looks at the relationship

between journal ranking measures and Scopus authoring in Public Affairs, the

tools with the more predictive authoring result. Figure 13 shows impact results

ranked by SNIP, the most predictive of the three measures in Scopus authoring.

Ranked in descending order of SNIP values, Scopus does consistently provide

comparatively stronger authoring relationships than either Impact Factor or

Eigenfactor.

Figure 11

Journals selected using the History fund.

Figure 12

Journals selected using the Forestry fund.

Figure 13

Public Affairs fund titles and impact

measures.

Discussion

As

both login demographics and interdisciplinary use are collected, correlated

evidence of patterns of use emerge, resulting in a more accurate picture of

activity. The results suggest practical ways to inform selection decisions. Web

of Science provides more complete information on citing activity by faculty

peers for subscribed titles, while Scopus provides better information on

authoring activity by local faculty for subscribed journals. One solution is to

use both the Web of Science Local Journal Use Reports and Scopus tools. If LJUR

is too pricey but one subscribes to Web of Science, the latter can be searched

by institutional affiliation (though this can be labour-intensive).

Given the trend toward more centralized

collection development, it is still critical to obtain liaison/subject

coordinator input no matter what datasets are used for decision making. Not

only do liaisons have the deepest understanding of disciplinary level use and

quality, but as this research demonstrates, the “best fit” metric may vary both

within a broad discipline category as well as between disciplinary categories.

Such analysis also provides proactive evidence

of value to the academy. The process of looking at impact provides the same

frame or structure across disciplines, often with very different outcomes.

Furthermore, this evidence of value can be used to defend any local library

“tax” that academic departments pay, as well as to promote services that help

faculty demonstrate their research impact, e.g., for tenure portfolios.

Conclusion

Collecting and correlating authorship and

citation data allows patterns of use to emerge, resulting in a more accurate

picture of activity than the more often used cost-per-use. To find the best

information on authoring activity by local faculty for subscribed journals, use

Scopus. To find the best information on citing activity by faculty peers for

subscribed titles, use Thomson Reuters’ customized LJUR report, or limit a Web

of Science search to local institution. The Eigenfactor and SNIP journal

quality metrics results can better inform selection decisions, and are publicly

available. Given the trend toward more centralized collection development, it

is still critical to obtain liaison input no matter what datasets are used for

decision making. This evidence of value can be used to defend any local library

“tax” that academic departments pay as well as promote services to help faculty

demonstrate their research impact.

References

Anderson, I. (2011, October). Shaking

up the norm: Journal pricing and valuation. Paper presented at the meeting

of the ARL-CNI 21st Century Collections Forum, Washington, D.C. Retrieved from http://www.arl.org/storage/documents/publications/ff11-anderson-ivy.pdf

Appavoo, C. (2013). What’s the big deal?

Collection evaluation at the national level [PowerPoint slides]. Retrieved from

http://connect.ala.org/files/CRKN_ALA_2013%20bullets.ppt

Blecic, D. D., Wiberley, S. E., Fiscella, J. B., Bahnmaier-Blaszczak,

S., & Lowery, R. (2013). Deal or no deal? Evaluating big deals and their

journals. College & Research

Libraries, 74(2), 178-194. http://dx.doi.org/10.5860/crl-300

Bucknall, T., Bernhardt, B., & Johnson, A. (2014). Using cost per

use to assess big seals. Serials Review,

40(3), 194-196. http://doi.org/10.1080/00987913.2014.949398

Chew, K., Stemper, J., Lilyard, C., & Schoenborn, M. (2013,

October). User-defined value metrics for electronic journals. Paper presented

at the 2012 Library Assessment Conference: Building Effective, Sustainable,

Practical Assessment, Charlottesville, VA. Washington, DC: Association of

Research Libraries. Retrieved from http://purl.umn.edu/144461

De Groote, S. L., Blecic, D. D., & Martin, K. (2013). Measures of

health sciences journal use: a comparison of vendor, link-resolver, and local

citation statistics. Journal of the

Medical Library Association,101(2), 110-119. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.3163/1536-5050.101.2.006

Dewland, J. C. (2011). A local citation analysis of a business school

faculty: A comparison of the who, what, where, and when of their citations. Journal of Business & Finance

Librarianship, 16(2), 145-158. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08963568.2011.554740

Harzing, A. W. (2010). Citation

analysis across disciplines: The impact of different data sources and citation

metrics [White paper]. Retrieved from http://www.harzing.com/data_metrics_comparison.htm

Helman, D. (2008). Wendt Library

– Faculty Collections Survey 2008. Unpublished manuscript, University of

Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, WI.

Jubb, M., Rowlands, I., & Nicholas, D. (2013). Value of libraries:

Relationships between provision, usage, and research outcomes. Evidence Based Library and Information

Practice, 8(2), 139-152. http://dx.doi.org/10.18438/B8KG7H

Jurczyk, E., & Jacobs, P. (2014). What's the big deal? Collection

evaluation at the national level. portal:

Libraries and the Academy, 14(4), 617-631. http://dx.doi.org/10.1353/pla.2014.0029

Kimball, R., Stephens, J., Hubbard, D., & Pickett, C. (2013). A

citation analysis of atmospheric science publications by faculty at Texas

A&M University. College &

Research Libraries, 74(4), 356-367. http://dx.doi.org/10.5860/crl-351

Knowlton, S. A., Sales, A. C., & Merriman, K. W. (2014). A

comparison of faculty and bibliometric valuation of serials subscriptions at an

academic research library. Serials Review,

40(1), 28-39. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00987913.2014.897174

Meyer, G. J., Finn, S. E., Eyde, L. D., Kay, G. G., Moreland, K. L.,

Dies, R. R., ... & Reed, G. M. (2001). Psychological testing and

psychological assessment: A review of evidence and issues. American Psychologist, 56(2), 128-165. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.56.2.128

Nieder, C., Dalhaug, A., & Aandahl, G. (2013). Correlation between

article download and citation figures for highly accessed articles from five

open access oncology journals. SpringerPlus, 2(1), 1-5. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/2193-1801-2-261

Nisonger, T. E. (2008). The “80/20 rule” and core journals. The

Serials Librarian, 55(1-2), 62-84. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/03615260801970774

Priem, J., Piwowar, H. A., & Hemminger, B. M. (2012). Altmetrics in the wild: Using social media

to explore scholarly impact [arXiv preprint]. Retrieved from http://arxiv.org/html/1203.4745v1

Stemper, J. A., & Jaguszewski, J. M. (2004). Usage statistics for

electronic journals: an analysis of local and vendor counts. Collection Management, 28(4), 3-22. http://dx.doi.org/10.1300/J105v28n04_02

University of California Libraries’ Collection Development Committee.

(2007). The promise of value-based

journal prices and negotiation: A UC report and view forward [White paper].

Retrieved from http://libraries.universityofcalifornia.edu/groups/files/cdc/docs/valuebasedprices.pdf

Van de Walle, S., & Van Delft, R. (2015). Publishing in public

administration: Issues with defining, comparing, and ranking the output of

universities. International Public

Management Journal, 18(1), 87-107. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10967494.2014.972482

Wilson, J., & Li, C. (2012, February 13). Calculating scholarly

journal value through objective metrics. CDLINFO

News. Retrieved from http://www.cdlib.org/cdlinfo/2012/02/13/calculating-scholarly-journal-value-through-objective-metrics/

![]() 2016 Chew, Schoenborn, Stemper, and Lilyard. This

is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

2016 Chew, Schoenborn, Stemper, and Lilyard. This

is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.