Introduction

Library development

greatly benefits from continuous input of internal and external intelligence to

be successful (Davies, 2008). Statistics are collected in all Swedish

libraries as part of the government-mandated Official Statistics of Sweden (Statistics

Sweden, 2016). The

impressive array of data, produced and communicated to national authorities

every year, can also be of strategic use locally (Høivik, 2008). In addition, qualitative data is collected

regularly as patrons are surveyed, introducing ideas and user perspective into

the organization.

Quality assurance and

strategic planning are vital parts of systematic public management (Young, 2003). For libraries, it is not uncommon that these

types of systems originate from the parent organization (Broady-Preston

& Lobo, 2011). The University of Gothenburg implemented a

university-wide quality assurance framework in 2001 (Göteborgs

universitet Universitetsstyrelsen, 2001). A new strategic planning system has been in

place at University of Gothenburg since 2013 (Göteborgs

universitet, 2013). In addition, a number of departments (such

as environment, worker’s, and fire safety) have their own systematic processes

and auditing procedures to expand the picture.

All these tools are

useful and valuable for improving and making our libraries more effective (Dean &

Sharfman, 1996). However, they can feel unorganized and hard

to communicate to the staff and stakeholders. Gothenburg University Library set

out to condense the majority of these activities into one process. Effort was

put into building a user-focused and staff-centered bottom-up workflow. The

system was further enhanced with a longer-term strategic cycle, which also

relies on staff input and statistical intelligence.

Methods and Results

Building the Quality

Cycle

The quality system framework, established by the University of Gothenburg

Board, mandated all university schools and the library to set up quality

systems. The nature of the local quality systems was not described in detail,

but left to the different schools to formulate, based on individual circumstances.

Later, a system auditing procedure was put in place to give collegial advice on

the development of the local systems.

The university library

implemented its first quality system in 2003-4, when a set of goals was defined

and assessed throughout the organization (Götesborgs

universitet Biblioteksnämnden, 2003). The system was then developed and improved

upon in 2008 and 2012.

Describing the Quality

Cycle

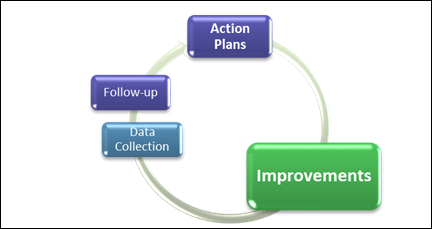

The process, as it is in effect now, is based on a follow-up/planning period in

January/February of each year (Figure 1).

In the planning stage,

each library team (7-15 staff) defines a few projects (activities) of varying

size which should be completed before the end of the year. The resulting

activity plans are gathered from throughout the organization and published on

the library intranet. To strengthen the strategic relevance, a number of

activities are selected from the current library strategic plan by the library

leadership and assigned to the individual teams prior to the planning. This

means that each team may have one or two activities which must be included in

the activity plan in order to keep pace with strategic goals.

Figure 1

Quality cycle.

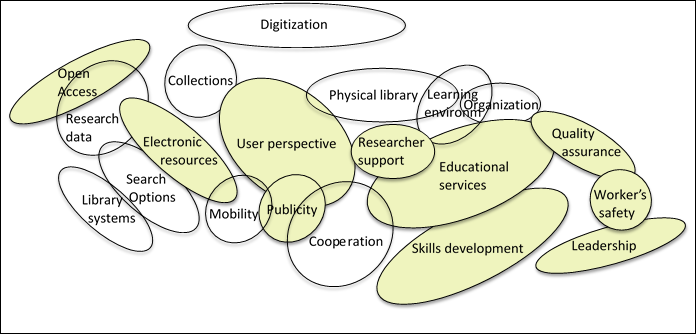

Figure 2

Input to follow-up

activities.

To give the staff

teams a current background for their work, the planning period is preceded by a

follow-up and assessment routine (Figure 2). During follow-up, the activity

plans from the previous year are accounted for. In addition, the teams are

asked to study and comment on data from a number of other sources. Each year

has a follow-up theme. Centrally prepared reports are presented to the teams.

The latest user survey may be distributed, or a report of improvement

suggestions from staff or users can be presented. Staff participation often

leads to discussions of the current matter, for instance, why visitor numbers

are down, or the nature of the enquiries at the front desk.

The follow-up period

has proven to be a great inspiration for activity planning, which normally is

scheduled for the following team meeting. It also allows follow-up activities from

auxiliary management systems to be incorporated, making them more accessible to

the staff.

Building the Strategic

Cycle

Some management activities are repeated less frequently than once a year. One

of these is the development of the library strategic plan. A weakness in

quality assurance work is that it does not necessarily make the library

activities more focused or more effective. A long-term direction has to be

established.

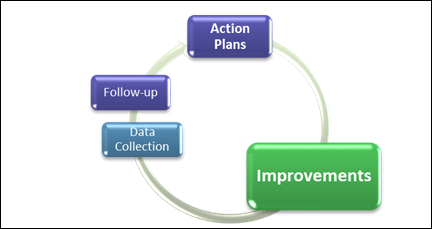

The way to handle this

challenge was the creation of a Strategic Cycle (Figure 3). Early in the year

before a new strategic plan is set to take effect, external intelligence is

gathered in a more deliberate way than normal. Vision statements and other

long-term documents are revisited and revised. Later that year, seminars and

group discussions consolidate the material, and a new strategic plan is

drafted. After approval, once the plan has taken effect, the quality cycle is

used to drive the implementation.

Collection of

Intelligence

Intelligence collection is key to the strategic cycle. One useful technique is

benchmarking, which has been performed for a number of different themes using a

method derived from SIQ (Nilsson, Örtelind, & Östling, 2002). The ideal benchmark activity often starts

with a specific need, and the definition of a number of themes of interest.

Libraries are then scanned to find peers with assets in the selected areas.

Identified libraries are contacted and invited to add themes of their own. The

library leadership teams then meet to present their library’s activities in the

selected areas of interest. This often gives a richer understanding of best

practices within the selected themes.

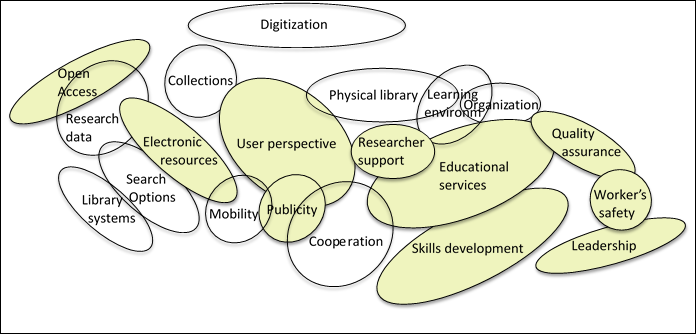

The intelligence

collection process preceding the latest completed strategic cycle produced a

trend cloud, which then was used to develop and focus the plan (Figure 4).

Figure 3

Strategic cycle.

Figure 4

Trend areas from

intelligence collection 2012. Main areas accented.

Conclusions

The implemented Quality and Strategic Cycle at Gothenburg University Library

has contributed to more user-focused and experience-driven library activities.

Staff ownership has facilitated collective involvement in addressing the

toughest issues for our changing library environment. Many more employees are

now actively involved in change processes, and there is a wider understanding

of developments as a result of allowing staff to systematically contribute to

changes in their immediate environment.

There is great benefit

from including assessment results in systematic change processes. Many surveys

and studies of statistical data have precipitated a large number of action

plans throughout the years, but the follow-up and implementation steps have

been more difficult. Statistical data, especially data collected for national

statistics, was rarely used for library development. The definition of a yearly

process into which data and previous findings can be funneled has been shown to

be a powerful driving force for implementing meaningful change.

References

Broady-Preston, J., & Lobo,

A. (2011). Measuring the quality, value and impact of academic libraries: The

role of external standards. Performance

Measurement and Metrics, 12(2), 122-135.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/14678041111149327

Davies, J. E. (2006). Taking

a measured approach to library management: Performance evidence applications

and culture. In T. Kolderup Flaten (Ed.), Management,

marketing and promotion of library services based on statistics, analyses and

evaluation (pp. 17-32). Berlin, Boston: K. G. Saur. http://dx.doi.org/10.1515/9783598440229.17

Dean, J. W., & Sharfman,

M. P. (1996). Does decision process matter? A study of strategic

decision-making effectiveness. Academy of

Management Jounal, 39(2), 368-392. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/256784

Høivik, T. (2006). Comparing

libraries: From official statistics to effective strategies. In T. Kolderup

Flaten (Ed.), Management, marketing and

promotion of library services based on statistics, analyses and evaluation (pp.

43-64). Berlin,

Boston: K. G. Saur. http://dx.doi.org/10.1515/9783598440229.43

Nilsson, H. L., Örtelind, A.-B., & Östling, M.

(2002). Benchmarking : att lära av andra – en handbok i benchmarking

[Benchmarking: To Learn from Others – A Handbook in Benchmarking] Göteborg:

SIQ.

Statistics Sweden. (2016). Official

Statistics of Sweden. Retrieved from http://www.scb.se/en_/About-us/Official-Statistics-of-Sweden/

Göteborgs universitet (2013).

Planering och uppföljning. [Planning and Assessment] Retrieved from http://medarbetarportalen.gu.se/vision2020/Planering-och-uppfoljning/

Göteborgs universitet

Universitetsstyrelsen (2001-06-11). Göteborgs universitets

kvalitetssystem. [Quality System for the

University of Gothenburg]

Göteborgs universitet

Biblioteksnämnden. (2003). Kvalitetssystem for Göteborgs universitetsbibliotek.

[Quality

System for Gothenburg University Library] Retrieved from point 7 on

http://www.ub.gu.se/info/organisation/biblnamnd/protokoll/arendelistor/BNarenden031119/BNarende031119.pdf

Young, R. D. (2003).

Perspectives on Strategic Planning in the Public Sector. Retrieved from

http://www.ipspr.sc.edu/publication/perspectives%20on%20Strategic%20Planning.pdf

![]() 2016 Carlsson. This is an Open Access article

distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/), which

permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

2016 Carlsson. This is an Open Access article

distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/), which

permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.