Article

Exploring the Complexity of Student Learning Outcome

Assessment Practices Across Multiple Libraries

Donna Harp Ziegenfuss

Interim Head of Scholarship

and Education Services

University of Utah

Salt Lake City, Utah, United

States of America

Email: donna.ziegenfuss@utah.edu

Stephen Borrelli

Head of Library Assessment

Penn State University

Libraries

University Park,

Pennsylvania, United States of America

Email: sborrelli@psu.edu

Received: 15 Feb. 2016 Accepted:

26 Apr. 2016

2016 Ziegenfuss and Borrelli. This is an Open

Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

2016 Ziegenfuss and Borrelli. This is an Open

Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

Abstract

Objectives – The purpose of this collaborative

qualitative research project, initiated by the Greater Western Library Alliance

(GWLA), was to explore how librarians were involved in the designing,

implementing, assessing, and disseminating student learning outcomes (SLOs) in

GWLA member academic libraries. The original objective of the research was to

identify library evaluation/assessment practices at the different libraries to

share and discuss by consortia members at a GWLA-sponsored Student Learning

Assessment Symposium in 2013. However, findings raised new questions and areas

to explore beyond student learning assessment, and additional research was

continued by two of the GWLA collaborators after the Symposium. The purpose of

this second phase of research was to explore the intersection of library and

institutional contexts and academic library assessment practices.

Methods – This qualitative research study involved a survey of

librarians at 23 GWLA member libraries, about student learning assessment

practices at their institutions. Twenty follow-up interviews were also

conducted to further describe and detail the assessment practices identified in

the survey. Librarians with expertise in library instruction, assessment, and

evaluation, either volunteered or were designated by their Dean or Director, to

respond to the survey and participate in the interviews. Interview data were

analyzed by seven librarians, across six different GWLA libraries, using

constant comparison methods (Strauss & Corbin, 2014). Emerging themes were

used to plan a GWLA member Symposium. Based on unexpected findings, after the

Symposium, two GWLA researchers continued the analysis using a grounded theory

methodology to re-examine the data and uncover categorical relationships and

conceptual coding, and to explore data alignment to theoretical possibilities.

Results – Seventeen categories and five themes emerged from the

interview data and were used to create a 3-part framework for describing and

explaining library SLO assessment practices. The themes were used to plan the

GWLA Assessment Symposium. Through additional qualitative grounded theory data

analysis, researchers also identified a core variable, and data were

re-evaluated to verify an alignment to Engeström’s Activity and Expansion Theories

(Engeström, 2001, 2004).

Conclusions – The findings of this multi-phased qualitative

study discovered how contextual, structural, and organizational factors can

influence how libraries interact and communicate with college departments, and

the larger institution about student learning outcomes and assessment. Viewing

library and campus interaction through the activity theory lens can demonstrate

how particular factors might influence library collaboration and interaction on

campuses. Institutional contexts and

cultures, campus-wide academic priorities, leadership at the library level, and changing roles of librarians were all

themes that emerged from this study that are important factors to consider when

planning the design, implementation, assessment and dissemination of library

SLOs.

Introduction

The

purpose of this research was to uncover the various types of student learning

outcomes and assessment practices at GWLA member academic libraries. Themes

identified from research data were then used to organize and plan a symposium

focused on student learning outcomes assessment. Questions that emerged from

the survey and interview findings also prompted a need for additional research

to uncover relationships between institutional and library culture with

assessment practices. Therefore, this paper will present the methods, results

and findings from Phase 1 of the research, the pre-symposium survey and

interview data analysis, as well as the additional Phase 2 post-symposium

grounded theory analysis. Finally, findings from the grounded theory analysis will

be used to present three different institutional profile vignettes as examples

of how activity theory might be utilized to rethink library-institutional

interactions.

A charge

from the Greater Western Library Alliance (GWLA) formed the Student Learning

Outcomes (SLO) Taskforce Committee to investigate learning assessment practices

at GWLA member libraries and how academic libraries are impacting student

learning outcomes assessment. A qualitative research approach was selected for

this study because it was the best method for gathering rich and descriptive

information about student learning outcome assessment practices. Members of the

taskforce worked on subcommittees to create the survey, implement the survey,

design the interview protocol, conduct the interviews and analyze the interview

data. The taskforce membership included library representatives from eleven

institutions: Arizona State University, Brigham Young University, Texas Tech

University, University of Arizona, University of Colorado-Boulder, University

of Houston, University of Illinois Chicago, University of Kansas, University of

Missouri, University of Nevada Las Vegas, and University of Utah.

This paper

outlines the processes and findings for this collaborative qualitative research

project. Initially, representatives from 23 institutions were surveyed. From

the survey, representatives from 20 GWLA academic libraries volunteered to be

interviewed about the assessment practices in their library, as well as, campus

assessment practices at the institution and department/college levels. Analysis

of interviews resulted in themes and related categories and in the development

of a conceptual framework. This framework was used to design a three-day GWLA

Student Learning Assessment Symposium (GWLA, 2013). Going beyond that analysis,

two librarians continued to re-examine data using a more rigorous grounded

theory process to uncover a core variable and generate theory that can be used

to guide library reflection and analysis at any institution.

Literature

Review

The library value movement posits that in the current environment,

connecting library services with institutional priorities to demonstrate

library impacts results in increasing library relevancy (Kaufman &

Watstein, 2008; Menchaca, 2014; Oakleaf, 2010; Pritchard, 1996). In the seminal

work on library value, multiple approaches for academic libraries to develop

institutional relevance are identified. Developing and

assessing student learning outcomes is just one option identified for

demonstrating library value in relation to student learning (Oakleaf, 2010;

Hiller, Kyrillidou & Self, 2006; Pan, Ignacio, Ferrer-Vinent & Bruehl,

2014). Published evidence of library impact on student learning has been

historically disconnected from institutional outcomes, and generally focuses on

individual librarian/faculty collaboration, rather than programmatic approaches

(Oakleaf, 2011). Hufford (2013) contends, in a 2005-2011 review of the library

assessment literature, that, while traditional library inputs and output

measurements remain valuable, libraries are increasingly focusing on institutional

priorities and assessing student-learning outcomes programmatically, to uncover

institutional impacts.

As the library value

literature indicates, it is also important to investigate higher education

change and organizational development issues more broadly (Barth, 2013; Kezar, 2009). Economic, social, technological,

and cultural issues are currently emerging and driving change in new directions

on many campuses (Altbach, Gumport & Berdahl, 2011; Kezar &

Eckel, 2002; Kyrillidou, 2005). There are calls for transformational change (Eckel & Kezar, 2003), encouragement for ‘disruptive’ education tools (Christensen & Eyring, 2011), and a reinvention of the college experience (Hu, Scheuch, Schwartz, Gayles, & Li, 2008). In addition, findings from Phase 1 of this

study identify a need for investigating how higher education contextual and

organizational structures are influencing how libraries are changing and

functioning on campuses. One theory, Activity Theory (Engeström, 2001, 2004; Engeström, Miettinen, & Punamäki, 1999), aligns well with the emerging library

literature and the higher education change literature, as well as the results

from this study. This Activity Theory framework, grounded in the seminal

constructivist theory of Vygotsky (Roth & Lee,

2007; Vygotsky, 1980) has been utilized in

many studies to theorize and describe a variety of work and learning

environments or systems through the structure of goals and objects that include

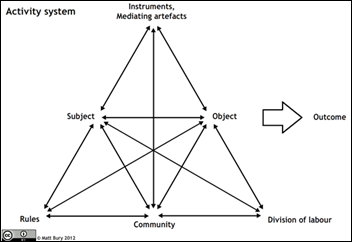

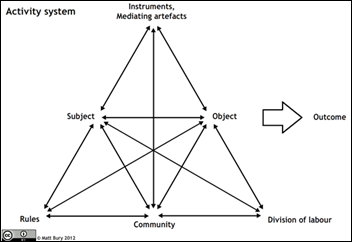

activity towards an object, tools, community structures, and rules (Figure 1).

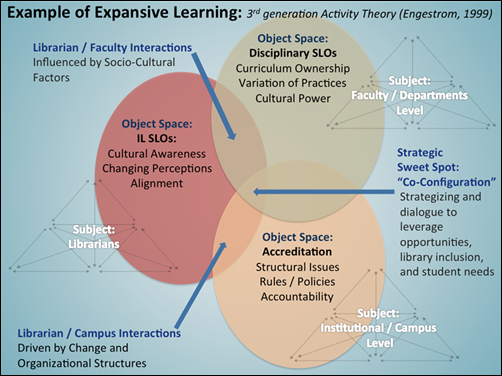

A second theory, Expansive Learning (Engeström, 2001,

2004), that is an extension

of activity theory, focuses on the interactions and change between multiple

activity systems. As libraries transform and become more embedded in the

institutional structure and culture, awareness of other campus activity systems

and interactions will only become more critical to demonstrating library value

and success.

Figure 1

Activity theory model diagram (Bury, 2012).

Phase 1 Pre-symposium: Survey and Interview

Methodology, Results and Findings

Phase 1: Methods

This qualitative study

was conducted in two phases. In the first phase, GWLA librarians collaborated

to conduct a survey and interviews to identify the SLO assessment practices of

GWLA academic librarians (See Appendix A and B for the survey questions and interview

script). The survey was designed and distributed electronically. A taskforce

sub-committee of librarians worked to design, implement, and evaluate the

survey responses. Another sub-committee of librarians designed the interview

protocol and conducted the interviews. Audio interview files for 20 interviews

were transcribed by an external transcription service. The follow-up

interviews, which further described and informed the survey responses where

then coded and analyzed by a third sub-committee of seven librarians, using a

grounded theory approach (Strauss & Corbin, 2014). Librarians worked in

pairs to triangulate coding results. All of this research was conducted with a

purpose of planning for a GWLA Assessment Symposium and prior to the 2013 Symposium.

In the second phase of the research, 2 of the original 7 librarians who helped

to code and analyze the 20 interviews continued to analyze data and took the

analysis to the next step of theory generation. This data analysis took place

after the Symposium.

An electronic survey

was distributed to the GWLA membership, and 23 GWLA libraries (72%) responded

to the survey. Survey respondents were either selected by their Library Dean or

Director, or volunteered to take the survey because they were a librarian with

assessment or instruction expertise and aware of student learning outcomes

assessment practices on their campuses. The selection and position of the

interviewee(s) varied based on the organizational structure of each of the

academic libraries and that decision was left up to the survey respondents on

who should represent the library and participate in the survey and interviews.

However, all interviewees were instructed to respond to questions on behalf of

their library and not on their individual projects. The respondents answered a

series of questions about the presence and assessment of SLOs on their

campuses. The purpose of the survey was to uncover which libraries had

established SLOs and were using information literacy (IL) SLOs, and at what

levels of the institution the SLOs existed or were being assessed. Librarians

were also asked if they were assessing their faculty/librarian collaborations.

From the 23 survey

respondents, 20 people either volunteered for a follow-up interview, or

appointed someone else as the designated library representative. Librarians

were invited to participate based on their role in the library, either with

assessment or library instruction, and also for their ability to discuss the

status of assessment at other levels of their institution. In 65% of the cases,

the same person who responded to the survey also consented to the interview. In

35% of the cases, several people participated in the interview to speak to

multiple aspects of the instruction and assessment topics. For example, an

instruction librarian and an assessment librarian were interviewed together in

some cases at institutions. Interview participants were encouraged to extend

invitations to other assessment and instruction librarians or staff to

participate in the interview if one person might not be able to answer all of

the questions.

A plan was also

established for conducting interviews and collaborative qualitative analysis of

the interviews. Follow-up interviews began in Spring 2012 and were completed in

December 2012. Data analysis was ongoing during the interview process and

completed in Spring 2013. An additional bibliography was also compiled on

published reports of assessment evidence, practices, and innovations, which

were gleaned from topics raised in the 20 interview transcripts. This data was

used to recruit presenters for the GWLA November 2013 Librarians Partnering for

Student Learning Symposium that was held at the University of Nevada, Las

Vegas. Throughout the spring, summer and winter of 2012 interviews of the

follow-up contacts were conducted by telephone via interview teams. From these

interviews, written summaries were created, interviews were audio-recorded, and

the audio files were transcribed. The transcribed transcripts were then submitted

to the qualitative analysis team, where pairs of researchers analyzed and

triangulated the interview data and compiled the findings. The transcripts were

analyzed using grounded theory qualitative methodologies using open and axial

coding strategies (Strauss & Corbin, 2014). For the open coding analysis,

the researchers individually read the transcripts and created preliminary codes

to describe the text. Then the research pairs compared their coding and moved

into the axial coding stage where they looked for relationships and connections

between the codes and created larger categories. To begin the interview

analysis, pairs of researchers coded four interview transcripts, one pair for

each interview. Each researcher coded his/her interview independently first and

then member-checked coding with his/her partner who had also coded the same

interview. Each pair submitted a single set of coding. The coding from the four

interviews was then compiled and analyzed for themes. Since not all

institutions had a qualitative analysis package like NVivo or Atlas.ti to

conduct qualitative analysis, the research team used Microsoft Excel to conduct

the qualitative data analysis and to compile the results of the survey and

interviews into themes and topics for further study. Tutorials on using Excel

to do qualitative analysis were provided to researchers. From the first set of

four interviews, a preliminary set of 17 categories was uncovered and used to

define the codebook for the rest of the research process. The 17 categories

were consolidated and re-evaluated to create a set of 5 major themes. A

framework was developed from the themes and used to plan the GWLA Student

Learning Outcome Symposium in 2013 (GWLA, 2013).

Phase 1: Survey

Results

The survey results

demonstrated that the presence and assessment of information literacy SLOs at

GWLA institutions occurs at a variety of levels. Fifty-seven percent of the 23

institutions that responded to the survey reported that they have campus-level

SLOs, but only 26% reported that those campus-level SLOs were assessed. A

similar disparity was identified at the college/department level between the

presence and assessment of SLOs with 61% reporting the presence of SLOs but

only 26% reporting assessment of the SLOs. However, at the library level, 65%

of institutions reported the presence of SLOs, and 48% reported that the SLOs

were assessed. In addition, when institutions were asked if librarian/classroom

faculty interactions were assessed, 61% (14 of the 23 institutions) reported that

they do assess these types of collaborations and 35% (8 institutions) reported

they do not assess these collaborations, one institution reported that they do

not know if these types of collaborations were assessed. The gap between what

institutions reported about the presence of SLOs, and the actual assessment of

SLOs, drove the question formation for follow up interviews with a purpose of

trying to identify how SLOs are assessed.

Phase 1: Interview

Results

Audio-recorded

interviews were conducted and transcribed. Analysis of the first 4 interviews

resulted in the identification of 484 codes, organized into 71 categories.

These categories were analyzed using a recursive process of recoding,

collapsing and combining codes, and renaming of categories until the remaining

categories were deemed to be unique. From this process, 17 unique core

categories were identified and defined. The 17 original categories were: 1) strategies for planning, implementing

& integrating SLOs; 2)

roles/responsibilities for assessment of SLOs; 3) collaboration; 4) communication

issues; 5)

tools-instruments-resources for SLOs; 6)

accountability & reporting of SLOs; 7) curriculum & instruction; 8) departmental relationships; 9)

culture and priorities issues; 10)

structures, policies, and administration; 11) professional development; 12)

challenges; 13) leadership; 14) change related; 15) opportunities; 16) general

(SLO catch-all); and 17) information

literacy topics. These categories were then used to code the remaining

interviews. No new categories emerged from the remaining 16 interviews

indicating data saturation.

During the second

round of coding, the 17 categories of codes were collapsed and refined into 5

main themes. The five themes were: 1)

curriculum and instruction; 2) strategies

for planning, implementing and integrating SLOs, 3) collaboration and communications issues, 4) roles/responsibilities for assessment & SLOs; and 5) SLOs structures, policies, and

administration. These five themes were returned to the researchers for

confirmation; each researcher taking one or two themes, to verify that no

additional themes had emerged. Using the five themes and code frequency data, a

conceptual framework was constructed to relate and explain the themes. For triangulation

and confirmation purposes, another GWLA taskforce member, who had not been

involved in the coding process, reviewed and refined the framework. The

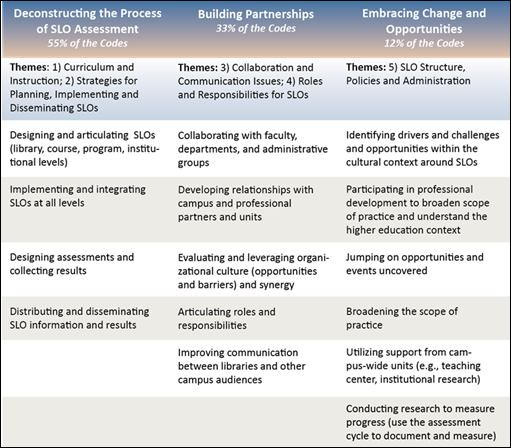

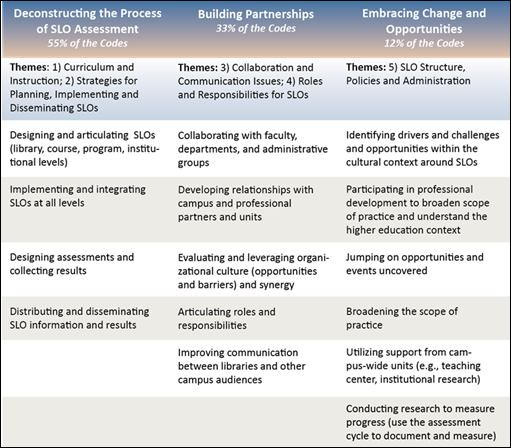

resulting framework (Figure 2) consists of three main parts: Deconstructing the Process of SLO Assessment,

Building Partnerships, and Embracing Change and Opportunities.

Since the main focus of the interviews was to uncover SLO practices and

processes across GWLA institutions it is not surprising that 55% of the coding

resides in the first column of the matrix that includes two of the five themes

and coding about SLO design, implementation, assessment and dissemination. The

framework structure, across the rows, aligns the SLO design and assessment

process to other cultural, contextual, and organizational institutional

factors. The codes and themes in the second and third columns, although smaller

in number, were consistently present and related back to the main SLO

assessment theme.

Figure 2

Conceptual framework for designing, implementing, assessing, and disseminating

SLOs.

Phase 1: Survey and Interview Discussion

The conceptual framework

for designing, implementing, assessing, and disseminating SLOs (Figure 2),

developed from the consolidated GWLA data in the first phase of this study, can

provide guidance for individual libraries as they work to evaluate their own

contributions to campus efforts related to articulating, embedding, and

assessing of SLOs. This conceptual framework emphasizes the importance of

building relationships, embracing change and opportunities, and considering

contextual and organizational structures when planning or sustaining successful

SLO design and implementation projects. These findings are in line with current

library research that focuses specifically on developing strategies for

building library-faculty collaboration and trust and consideration for the

complex set of contextual factors that can vary widely across institutions (Phelps & Campbell, 2012; Oakleaf, 2010). These factors may become critical or pivotal

barriers or possible opportunities related to successful SLO implementation and

dissemination. Findings from this study indicate there is no one magic bullet

method for integration of library IL SLO or successful SLO assessment implementation.

The themes of communication,

collaborations/partnerships, embracing opportunities, addressing challenges, and the rethinking of roles and

responsibilities were evident across all institutions that participated in

the study. However, the variation in contextual/cultural factors,

organizational structures, internal and external drivers, as well as,

leadership and levels of librarian proactivity also appear to result in very

different practices and outcomes. One librarian stated, “I think the library’s leadership

needs to be more proactive in promoting the library’s role as an information

literacy agency on campus.” Therefore, the conceptual framework can be used as

a roadmap to establish a process for developing library awareness, and

establishing priorities for libraries to take leadership roles. Findings from

this study suggest that institutions reflect on their own institutional context

and therefore tackle their unique complex situation in their own way. Best

practices or assessment strategies successful at one institution may not always

be easily replicated at other institutions. In addition, since each institution

and library may be at a very different place related to the articulation and

implementation of SLOs, this framework may provide a more flexible and holistic

option for reflection and strategic decision-making than a step-by-step

assessment implementation procedure or checklist approach to assessing SLOs.

Data from the study

also indicate that the planning process for campus-wide SLOs is often a

top-down or administrative initiative, resulting from accreditation concerns,

or an institutional focus on evidence based decision-making or assessment. One

example of how a university librarian described the assessment support

structure at the administrative level drove SLO assessment is,

“Our institution is very, very driven by the

evidence-base learning outcomes of students. We don’t just call them

student-learning outcomes. The Office of the Provost for the past five years

has made it very clear that every school has to have evidence based learning

outcome. And that of course does include information literacy at the

departmental level. So we are very much

embedded in this kind of approach.”

It was also noted

during analysis of this study data, at both the campus and library levels,

considerable efforts are being made to standardize assessment efforts.

Libraries and institutions are investing in the assessment effort, creating

assessment and planning librarians, or instruction and assessment positions to

focus efforts and provide accountability. One librarian discussed reactions to

accreditation needs and remarked, “One of the things that’s happening in

response to our last accreditation visit is that we have developed this Office

of Assessment of Teaching and Learning. And they are responsible for conducting

undergraduate assessment.” Many member institutions indicate that they are in

the process of learning to assess. Instruction librarians are applying many

approaches and instruments in their assessments, using qualitative and

quantitative methods often modeled after national tools like the Association of

American Colleges & Universities (AACU) Valid Assessment

of Learning in Undergraduate Education (VALUE) Rubrics (AACU, n.d.); Tool for Real-time Assessment of Information Literacy Skills (TRAILS) (Kent State University Libraries,

2016); Rubric Assessment of Information Literacy Skills (RAILS) (Oakleaf, n.d.); and Standardized Assessment of Information Literacy Skills (SAILS) (Kent State University Libraries,

2016).

Phase 2: Grounded Theory Methodology, Results,

and Findings

Phase 2: Methods

In Phase 2 of the

study, two of the original GWLA researchers continued the search for a core

variable and theoretical grounding, and continued to recode and reevaluate

data. The purpose of this phase of the research was to go beyond description

and uncover a theory or conceptual framework that would help institutions

analyze their own institutional context so they could better integrate the

academic library into their own institutional and contextual processes. The 17

categories and 5 themes from Phase 1 of the research created the foundation for

further analysis. The researchers returned to the literature to uncover

theoretical connections by recoding and categorizing through a process outlined

by Glaser & Holton, (2004). The research process included numerous coding

iterations, constant comparative analysis as well as member checking and

collaborative discussions and memoing about the data. After many iterations of

coding and recoding, the data and categories from Phase 1 of the research were

used to generate the theoretical construct discussed in this paper.

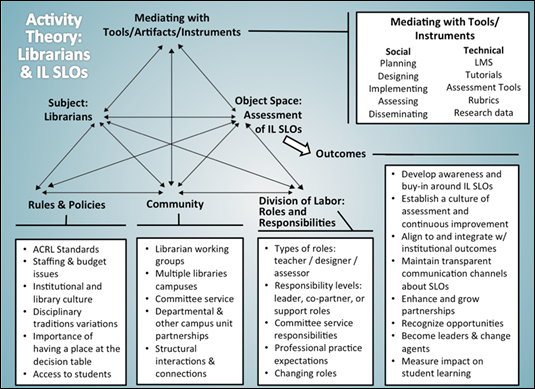

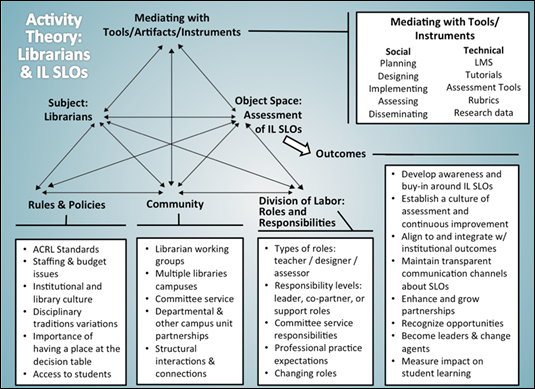

Figure 3

A library level activity system model (diagram created by Spencer, 2014).

Phase 2: Grounded Theory Results

The purpose of this

additional analysis was to take the study to the stage of theory

identification. Interview data were recoded and reanalyzed with a more

conceptual focus examining the three different institution levels of campus,

department/college, and library. Recoding resulted in a more detailed and

conceptual description of the SLO contextual factors and uncovered how

opportunities and challenges of the design, implementation and distribution of

SLOs are mediated at the different institutions. The six conceptual themes that

emerged from this additional coding process were building awareness, power and ownership, embedded in or on the fringe

of culture, opportunity advantages, organizational structure, and strategic leveraging. Taking a grounded

theory approach and revisiting the literature after revised conceptual coding

provided a broader lens of perspective and yielded an identification of

Activity Theory as a possible theoretical frame for understanding SLO

development and implementation as well as campus interactions. (Chaiklin, Hedegaard, Jensen & Aarhus, 1999; Engeström, Miettinen,

& Punamäki, 1999).

After theory

identification, the data were recoded once again to confirm alignment of the

data to the main components of the Activity Theory Model which consist of 4

components: 1) rules and policies, 2) community, 3) division of labor (roles and responsibilities), and 4) mediating tools and artifacts. Both

researchers recoded data again using these four components as codes and all

data could be aligned directly to these activity theory components. This

confirmed the suitability of this activity systems theory as a lens for

understanding the research data. Figure 3 demonstrates the alignment of

previous codes, categories, and themes from the conceptual framework analysis

of Phase 1, to the library Activity Theory model of the Phase 2 research.

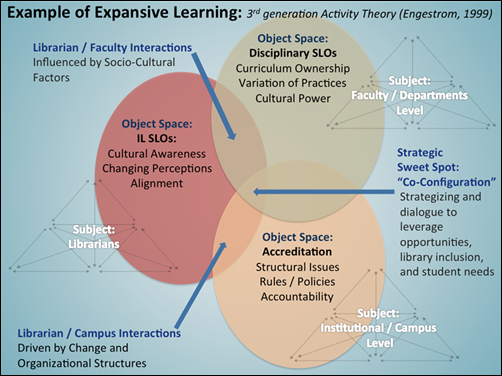

Further literature

searching exposed a related theory, Expansive Learning (Engeström &

Sannino, 2010) which is called third-generation activity theory, that offer

explanations for contextual factor interaction inherent in multiple systems.

Figure 4 demonstrates the alignment of the Phase 2 conceptual themes analysis

across the three different levels of an institution and at the intersection of

the three different activity systems. The interaction of all three systems or

what Engestrom calls “co-configuration” (Engeström, 2004), focuses on the theme

of strategic leveraging of opportunities, challenges and needs.

Figure 4

Intersections of three institutional activity systems.

Phase 2:

Grounded Theory Discussion

As related to a

finding from Phase 2 of this study, the researchers contend that the activity

of planning, designing, assessing, and disseminating SLOs is mediated through

tools, processes, rules, and community interactions. Re-examination of the data

using the activity theory model focused our analysis more on the contextual

factors influencing SLOs and less on the actual SLO assessment. The highest

occurrence of coding related to the rules and policies component of the

activity theory model, which was located in the institutional level data.

Although this may not be a surprising finding, it is important to be aware of

this when trying to work within an institutional context. In this study,

library/faculty interactions were influenced by socio-cultural factors and

library/campus level interactions were driven by organizational structure and

policy, as well as, by change. Themes such as accreditation as driver, change, leadership, organizational structure,

institutional culture, and getting a

place at the decision making table can now be connected to the

institutional level structures and culture. As librarians, it appears to be

critical to get plugged into the institutional culture. One librarian expressed

concern about this and stated,

… there is also the idea that on this campus,

and I think probably we’re not unique at all, people … still think of libraries

as the place that has the stuff and … they don’t necessarily look [at] the

librarians as partners in their teaching … and we don't have faculty status

here and so we’re not at the table.

Librarians should

consider taking a more proactive approach for inclusion in reform and change

initiatives, as well as employing routine operating procedures at their

institution, which may vary depending on the culture, leadership and engagement

of administrative units with assessment. One institution discussed the

challenges, but also the opportunities, when librarians take on new roles:

I would say the

biggest challenge that we've had is the fact that we have kind of taken on …

being experts on course design and so we have had pockets of faculties who sort

of questioned that or why our librarians doing this, they don't teach. So, it has been a big kind of image remake

and marketing opportunity for us.

This concept of librarians as change agents is

an emerging theme in the library (Pham &

Tanner, 2014; Travis, 2008).

Three

Institutional Vignettes

Of the 20 institutions

analyzed, institutional coding profiles varied which was evident in the frequency

of coding and categories. By exploring the data using the components of

activity theory, different priorities, foci, and initiatives at different

institutions were uncovered. Three different institutional profile vignettes

are presented below as examples to demonstrate the alignment of interview

coding, categories and themes at three different levels of the institution

(campus or institutional, department or college, and library) coded at the four

different components of Activity Theory.

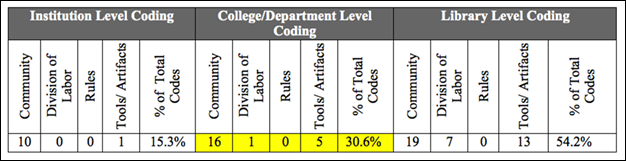

Vignette

1: The Bigger Picture

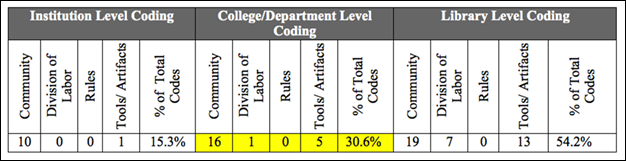

The first vignette is

an institution that stood out with exceptionally high coding frequency numbers

at the institutional and library levels and very low levels at the

college/department level (Table 1). This large public research institution,

reported SLOs at all three levels of the institution. Assessment is reportedly

driven by accreditation and there is a central assessment office, which may

account for the larger number of codes around the structure and process of

community at the institutional level. Library SLOs are aligned to the

institutional SLOs and there are assessment representatives in each unit. SLOs

developed out of the faculty senate with no library involvement but there is

evidence in the library of assessment professional development. At the library

level the high coding frequency for division of labor (roles and

responsibilities) is attributed to instances of discussion about the roles

librarians play in faculty collaboration and assessment of SLOs by designing assignments,

SLOs, collecting data, and disseminating SLOs. At the college/department level

however, there is a very low number of codes and the discussion in the

interview was only focused on the variation of assessment and culture across

departments.

Table 1

The Bigger Picture

University Focused Profile

Vignette 2: The

Community in the Library

The second

institution, also a large public university, has the largest concentration of

code frequencies at the library level, and specifically in the community

component of the library level (Table 2). This is a decentralized institution,

and a centralized SLOs assessment culture is a challenge, but locally in the

library there is a strong culture of assessment. Historically it appears this

institution has focused on library as place and collections, and less on

measuring student learning across the different levels of the institution.

Table 2

The Library Community

Profile

Vignette

3: A Lot of Teaching Responsibilities

In this last vignette the high coding frequencies at the College/Department

and Library level are attributed to a high percentage of the discussion focused

on discussing specific teaching projects in departments by librarians in the

interview. This research institution is in the process of moving to a liaison

model approach with faculty and therefore this may account for the higher

department/college coding frequency numbers (Table 3). The interviewee reported

that there is a good balance at this institution between research and teaching

but reports challenges of time constraints that dictate preparation issues.

There is more of a focus on curriculum development than assessment.

Table 3

The Library Focused on Teaching University Profile

As you can see from the brief vignettes of these three different GWLA

institutional libraries, each institution has slightly different priorities,

and in the interviews discussion was focused on different issues. Unique

situational factors and cultures can impact institutions differently. Findings

from this study emphasize the importance of developing awareness of your

institutional culture, organizational structure, and academic priorities. By

being aware of the environment and also tuned into emerging priorities and initiatives,

librarians will have opportunities to be proactive and step-up and engage with

their academic community. Libraries are positioned to increase their

organizational value by drawing on internal teaching expertise, developing new

skill sets in instructional design or other areas, and taking a proactive

stance where leadership or expertise is desired.

Conclusions

and Recommendations

The impact that a unique institutional culture and context has on the

ability of an organization to come together around designing, assessing and

disseminating SLOs was the most interesting finding in our data at both phases

of the research study. Some institutional efforts are bolstered through an

institutional commitment to evidence-based decision making while other

institutions reported that a decentralized organization, lacking a culture of

assessment, or lack of leadership could deter success in developing and

implementing SLOs. Other related limitations identified were academic freedom

issues, fear of negative impact on the tenure and promotion, and the location

and status of the library staff within the institutional structure. Many

libraries reported that they are actively building a culture of assessment and

creating positions to support SLO efforts. Additionally, information from the

interviews suggests that planning the process for SLOs is often a top down

initiative, resulting from accreditation drivers, or a presence or lack of presence

of an institutional focus on evidence or assessment. This is an area that might

merit further exploration and research in conjunction with the emerging

economic and political issues in higher education, which impact the ability to

staff and fund assessment efforts.

Another interesting aspect of the data analysis evolution centered on

differentiating between collaboration and campus-wide partnerships. As the

analysis progressed, the researchers saw collaborations as more related to

individuals working together, whereas partnerships focused more on developing

alliances or more long-term working partnerships with other campus units. These

are two very different things. It appears from the data that partnerships could

have a broader and more powerful impact on the work done in the library when

integrated with the opportunities for librarians interacting at different

campus levels, as compared to collaborations, which, focused on one-on-one

interactions with faculty. Therefore, one recommendation for future research is

to focus on studying how the presence of partnerships, as compared to

collaborations, specifically might impact the process of designing,

implementing, assessing and disseminating SLOs at various levels of the

institution.

Data indicated that curriculum development might be an area fruitful for

more study. As one interviewee in this study noted, “Often the process of

curriculum development does not include incorporating assessment. Instead,

assessment of learning is considered something to be addressed separately,

after the curriculum is developed.” This practice seems to run counter to the

current practice of ‘backward design’ (Fink, 2013), which was a successful

strategy used by one of the GWLA partners, and includes the sequential steps of

outcomes, assessment and then curriculum development. Additional research in

this curriculum design area could shed light on how libraries are integrating

assessment into curriculum level.

For the second phase of this study that linked the study data to Engestrom’s

Activity Theory, there are many implications and recommendations for library

practice. Analyzing the library landscape and how the library interacts,

interfaces and embeds within both the campus and departmental level could

benefit from strategic planning. This study data indicates the importance of

considering the broader aspects of interaction and partnership when designing,

implementing and disseminating IL SLOs. Awareness of the larger institution

culture and what initiatives are ‘hot’ and being funded will provide

opportunities for being proactive and engaging with the campus community.

Awareness of new initiatives might also provide opportunities to extend library

roles or take on new roles.

Even though each GWLA institution reported on a variety of methods,

strategies, and organizational approaches based on their unique contextual and

cultural structures for designing, implementing, assessing, and dissemination

of SLOs, there are however, commonalities in the motivators and drivers for

assessment across institutions, such as accreditation reviews, program

redesigns, and a desire to move to a more evidence-based driven culture.

Institutional contexts and cultures, campus academic priorities and

initiatives, leadership at both the institutional and library levels, and

changing roles of librarians; themes that emerged from this study are important

factors to consider when planning the design, implementation, assessment and

dissemination of IL SLOs.

Limitations of the

Study

As with any research project, there are process and methodology limitations

in this study. Not all GWLA member institutions participated in the study; this

was a purposive sample of volunteers interested in SLOs. Therefore, since

participants self-selected, participation may not be a true representation of

the consortium. In addition, although interviewees were librarians selected to

or volunteered to represent each institution, and selected by the role they

played at their institution, there may be other people at their institution

that could speak better to the institutional view of assessing SLOs. Therefore,

the information they provided may be limited by their own personal library role

and experience or limited by their personal knowledge about the larger

institution.

The data analysis in this study was done in Excel due to the lack of access

to expensive qualitative analysis software by the participating researchers.

Using qualitative software like NVivo or Atlas.ti would have enabled a more

comprehensive and accurate method for coding data and drawing conclusions. In

order to understand the study findings, it is also important to take into

account that the qualitative analysis part of this study was explorative in

nature with a purpose to identify possible topics or gaps for future GWLA

sponsored research study. It should also be noted that the negative and

positive coding instances of themes are not teased apart to isolate negative

and positive coding separately; they are combined together under the major

category/theme frequency numbers to demonstrate the need for exploration in the

most commonly described topics/issues area.

Finally, taskforce researchers with a variety of levels of qualitative

expertise conducted the research. Despite this limitation, the taskforce was able

to set up an effective process for collaborative research and triangulate

coding with partners. Now that the process is defined, it will be easier to

replicate this process and use this method as a possible model for conducting

GWLA collaborative qualitative research in the future; however, we did

experience some accuracy and logistical issues in this first attempt at

collaborative qualitative research using Excel.

References

Altbach, P. G., Gumport,

P. J., & Berdahl, R. O. (Eds.). (2011). American higher education in the

twenty-first century: Social, political, and economic challenges.

Baltimore, MD: JHU Press.

Association of American Colleges & Universities.

(n.d.) VALUE rubric development project.

Retrieved from: https://www.aacu.org/value/rubrics

Barth, M. (2013). Many

roads lead to sustainability: a process-oriented analysis of change in higher education. International

Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education, 14(2), 160-175. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/14676371311312879

Bury, M. (2012)

Activity system. Retrieved from: http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Activity_system.png.

Chaiklin, S.,

Hedegaard, M., Jensen, U. J., Aarhus. N (Eds.) (1999). Activity theory and social practice. Denmark: Aarhus University

Press.

Christensen, C.

M., & Eyring, H. J. (2011). The innovative university: Changing the DNA

of higher education from the inside out. Hobocken, NJ: John Wiley &

Sons.

Eckel, P. D.,

& Kezar, A. J. (2003). Taking the reins: Institutional transformation in

higher education. Westport, CT: Greenwood Publishing Group.

Engeström, Y.

(2004). New forms of learning in co-configuration work. Journal of Workplace

Learning, 16(1/2), 11-21. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/13665620410521477

Engeström, Y.

(2001). Expansive learning at work: Toward an activity theoretical

reconceptualization. Journal of education and work, 14(1),

133-156. 31(4), 293-302. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13639080020028747

Engeström, Y.,

Miettinen, R., & Punamäki, R. L. (1999). Perspectives on activity theory.

Boston, MA: Cambridge University Press.

Engeström, Y.,

& Sannino, A. (2010). Studies of expansive learning: Foundations, findings

and future challenges. Educational research review, 5(1), 1-24. http://dx.doi.org/doi:10.1016/j.edurev.2009.12.002

Fink, L. D.

(2013). Creating significant learning experiences: An integrated approach to

designing college courses. Hobocken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Glaser, B. G.,

& Holton, J. (2004, May). Remodeling grounded theory. In Forum

Qualitative Social Research, 5(2). Retrieved at: http://www.qualitative-research.net/index.php/fqs/article/view/607/1315Volume

Greater Western Library Alliance Student Learning Outcome Task Force

(GWLA). (2013, November). Librarians

partnering for student learning: Leadership, practice and culture assessment

symposium, information available at: https://sites.google.com/a/gwla.org/greater-western-library-alliance/Committees/slo.

Hiller, S., Kyrillidou, M., & Self, J. (2006). Assessment in North

American research libraries: a preliminary report card. Performance Measurement and Metrics, 7(2), 100-106. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/14678040610679489

Hu, S., Scheuch,

K., Schwartz, R., Gayles, J. G., & Li, S. (2008). Reinventing Undergraduate

Education: Engaging College Students in Research and Creative Activities. ASHE

Higher Education Report, Volume 33, Number 4. ASHE Higher Education Report,

33(4), 1-103. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/aehe.3304

Hufford, J. R.

(2013). A review of the literature on assessment in academic and research

libraries, 2005 to August 2011. portal: Libraries and the Academy, 13(1),

5-35. http://dx.doi.org/10.1353/pla.2013.0005

Kaufman, P., &

Watstein, S. (2008). Library value (return on investment, ROI) and the

challenge of placing a value on public services. Reference Services Review,

36(3), 226-231. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/00907320810895314

Kent State

University Libraries. (2016). RAILS: Standardized assessment of information literacy skills. Retrieved from: https://www.projectsails.org/

Kent State University Libraries. (2016). TRAILS: Tool for

real-time assessment of information literacy skills. Retrieved from: http://www.trails-9.org/

Kezar, A. J.,

& Eckel, P. D. (2002). The effect of institutional culture on change

strategies in higher education: Universal principles or culturally responsive

concepts? The Journal of Higher Education, 73(4), 435-460. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/aehe.2804

Kezar, A. (2009).

Change in higher education: Not enough, or too much?. Change: The Magazine

of Higher Learning, 41(6), 18-23. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00091380903270110

Kyrillidou, M.

(2005). Library assessment as a collaborative enterprise. Resource Sharing

& Information Networks, 18(1-2), 73-87. http://dx.doi.org/10.1300/J121v18n01_07

Menchaca, F.

(2014). Start a new fire: measuring the value of academic libraries in

undergraduate learning. portal: Libraries and the Academy, 14(3),

353-367. http://dx.doi.org/10.1353/pla.2014.0020

Oakleaf, M.

(n.d.), Rubric assessment of information

literacy skills (RAILS). Retrieved from: http://railsontrack.info/

Oakleaf, M.

(2010). The value of academic libraries: A comprehensive research review and

report. Chicago, IL: Association of College and

Research Libraries. Retrieved from: http://www.ala.org/acrl/sites/ala.org.acrl/files/content/issues/value/val_report.pdf

Oakleaf, M. (2011,

March). What’s the value of an academic library? The development of the ACRL

value of academic libraries comprehensive research review and report. Australian

Academic & Research Libraries, 42(1), 1-13. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00048623.2011.10722200

Pan, D.,

Ferrer-Vinent, I. J. & Bruehl, M. (2014). Library value in the classroom:

assessing student learning outcomes from instruction and collections. The

Journal of Academic Librarianship, 40(3), 332-338. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2014.04.011

Pham, H. T., &

Tanner, K. (2014). Collaboration between academics and librarians: a literature

review and framework for analysis. Library Review, 63(1/2),

15-45. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/LR-06-2013-0064

Phelps, S. F.,

& Campbell, N. (2012). Commitment and trust in librarian–faculty

relationships: A systematic review of the literature. The Journal of

Academic Librarianship, 38(1), 13-19. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2011.11.003

Pritchard, S. M.

(1996). Determining quality in academic libraries. Library trends, 44(3),

572-595.

Roth, W. M., &

Lee, Y. J. (2007). “Vygotsky’s neglected legacy”: Cultural-historical activity

theory. Review of educational research, 77(2), 186-232 http://dx.doi.org/10.3102/0034654306298273

Spencer, S. [graphic] (2014). A library level activity system model.

Travis, T. A. (2008).

Librarians as agents of change: working with curriculum committees using change

agency theory. New Directions for Teaching and Learning, 2008(114),

17-33. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/tl.314

Vygotsky, L. S.

(1980). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes.

Boston, MA: Harvard University Press.

Appendix A

GWLA Survey Questions

1.

Does your institution

have SLO's that address information literacy (i.e., critical thinking,

evaluation and synthesis of information) at any of the following levels?

Yes, No, Don’t Know responses for the:

a.

Campus Level

b.

College/Department

Level

c.

Library Level

2.

Does the library

assess information literacy SLO's at any of the following levels?

Yes, No, Don’t Know responses for the:

a.

Campus Level

b.

College/Department

Level

c.

Library Level

3.

Does the library

measure the impact of its collaborations with classroom faculty and other

academic partners? (Yes, No, Don’t Know responses)

4.

Would you, or someone

else at your institution, be available to answer more in-depth questions about

student learning outcomes and assessment at your institution?

Place to provide contact information

Appendix B

GWLA Interview Script

The purpose of the interviews was to get more detailed

information about the survey responses and therefore the possible interview

prompt script was developed from that structure.

1. Does your institution have SLO’s that address

information literacy (i.e. critical thinking, evaluation and synthesis of

information) at any of the following levels (Campus, College/Department, or

Library Levels) ?

If Yes:

o

Please describe.

o

Is there a central SLO

organization (taskforce, department, committee etc.) on your campus that

oversees college/unit student learning assessment?

o

Are they posted on a

publicly accessible website? If yes, please provide the url.

o

Was it a cooperative

effort to develop them? If yes, was the library

involved?

o

If they exist but not

formally stated, are they cultural? How do faculty know about them?

o

Did the SLOs have an

impact? What programs have changed as a result of the SLOs?

o

How have libraries

built partnerships on campus that have led to the development of SLOs within

courses and programs?

If No:

o

Are there future plans

to develop SLOs?

o

Is there a lack of

resources or personnel to develop SLOs

o

What actions should

the library be taking? Received comment that this question may be too leading. What is limiting the institution in creating

SLOs> What role does the library have in creating SLOs?

2.

Does the library assess information literacy SLO’s at any of the

following levels (Campus, College/Department, Library Levels)?

If Yes:

o

How are they assessed?

o

How often are they

assessed?

o

In what venues?

o

Are the results shared

with the wider academic campus?

o

Is it a cooperative

effort with faculty?

If No:

o

Are there future plans

to develop SLOs?

o

What actions should

the library be taking?

o

Is there a lack of

resources or personnel to develop SLOs?

o

Is there campus

support for developing SLOs?

o

Will academic faculty

be involved in their development? Why or why not?

3. Does the library measure the impact of its

collaborations with classroom faculty and other academic partners?

If Yes:

o

Which collaborations

does it measure?

o

How? When? How often?

o

Are academic faculty

included in the assessment?

o

Are the results shared

with academic partners?

If No

o

Any future plans to

assess them?

o

Is there campus support

for assessment?

o

Are there venues on

your campus for people interested in discussing, sharing, or collaborating on

institutional data or assessment?

o

Will academic faculty

be involved in the assessment? Why or why not?

4. Is there anything further you want to add or

discuss?

![]() 2016 Ziegenfuss and Borrelli. This is an Open

Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

2016 Ziegenfuss and Borrelli. This is an Open

Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.