Research Article

Facilitating Global Art Conversations: Availability of

Art Scholarship in Latin America

Alexander C. Watkins

Assistant Professor

University Libraries

University of Colorado

Boulder

Boulder, Colorado, United

States of America

Email: alexander.watkins@colorado.edu

Received: 2 Aug. 2016 Accepted: 13

Nov. 2016

![]() 2016 Watkins. This is an Open Access article

distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

2016 Watkins. This is an Open Access article

distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

Abstract

Objective

– As

art history becomes an increasingly global discipline, the question of

geographically equitable access to the scholarly knowledge produced at

universities in Europe and North America remains unexamined. This study aims to

begin to answer that question by investigating the availability of art

scholarship in Latin America.

Methods

– Sixty

university libraries in Latin America were checked for various kinds of access

to two major art history journals.

Results

– The

study found that access rates were low, and that the types of access available

were suboptimal.

Conclusion

– The

results suggest that the current level of access is insufficient to support

global scholarly conversations in art history and that current modes of

dissemination of scholarship are not reaching key audiences.

Introduction

The study of Latin

American art is a major endeavour at universities in Europe and North America, but how

much of the knowledge produced at these universities is available to Latin

American scholars? This study aims to answer the question of whether Latin

American scholars have access to the art scholarship of Europe and the United

States. It specifically focuses on scholars at Latin American research

universities working towards open scholarship. Recently, local art histories

have flourished as the discipline expands from its origins in Western Europe to

become a global enterprise, but even with this global expansion of study we

have not necessarily seen a concomitant expansion of scholarly communication.

The question of access is a key part of facilitating a global scholarly

conversation, as access to the theories and analyses that are current in the

scholarly literature of the global centre are required for international

communities to engage with these ideas and communicate their own perspectives

back to the centre.

A Note on Terminology

There are a multitude

of terms to describe the unequal global distribution of wealth caused by the

legacy of colonialism. In this paper, I use the centre-periphery terminology

and model as adapted to the world of scholarly publishing by Suresh Canagarajah

(2002). The global centre consists primarily of the United States and Western

Europe; however, there are many centres within countries that are part of the

global periphery, which also take advantage of colonial mechanisms to

concentrate wealth. There are also peripheries within centre nations, excluded

from the prosperity that is concentrated in certain areas of that nation. The

term centre scholarship in this paper includes scholarship produced by

academics at institutions with significant social and financial capital concentrated

but not exclusively found in North America and Western Europe. This unequal

distribution of resources and reputation has a particular impact on access to

the scholarly literature of the centre in the periphery, as this literature is

made available most commonly on a toll access basis.

Literature Review

The traditional

publishing model in which scholars give their articles to publishers, and those

publishers sell the articles back to scholars and their universities is one

that has hampered access to knowledge around the world. The rapid rate of

increase in journal prices means that scholars must be associated with

well-funded universities to access the full breadth of the scholarly

literature, and this tends to disproportionately affect the access of periphery

scholars. As early as 1995, this issue was discussed in Scientific American, which recounts journal cancellations in

libraries across the developing world. Although Latin America was found to have

the most access to major journals of the three regions surveyed, libraries in

Africa, India, and Latin America were all found to be lacking access to

necessary serials collections (Gibbs, 1995a). Sri Lankan scholar Suresh

Canagarajah vividly recounts his experiences trying to get access to scholarly

literature, when at his university it was unthinkable to get the latest

scholarly journal or book. He speaks directly to the fact that his work and

that of his peers was hampered without this access (Canagarajah, 2002).

Consequently, many periphery scholars must employ slow, expensive, or

convoluted work-arounds to deal with a lack of access, such as emailing article

authors or traveling specifically to visit centre libraries (Bonaccorso et al.,

2014). The purchasing power of developing world libraries is further taxed by

the extreme prices charged by academic publishers (Arunachalam, 2003; Davison,

Harris, Licker, & Shoib, 2005). Specifically in Latin America, limited

financing means that university libraries often have incomplete collections

with little ability to plan for the long term (Holdom, 2005; Terra Figari,

2007). However, at the date of writing there has been little to no research on

holdings of specific journals by periphery libraries, especially in humanities

disciplines. This has made it hard to quantify the extent of this lack of

access to journals. The problematic repercussions of this lack of access is

often framed as one of distributive justice, where academic paywalls have

recreated patterns of social exclusion and the dominance of the centre over the

periphery (Alperín, Fischman, & Willinsky, 2008; Gómez & Bongiovani,

2012).

Insufficient access to

scholarly publications creates a barrier to periphery scholars publishing in

centre academic journals. Keeping up with the frontier of knowledge development

in the scholarly literature of the centre is impossible without access to current

journals and databases (Teferra, 2004). This lack of access creates a tendency

to emphasize foundational works and to omit the latest developments of the

centre (Terra Figari, 2007). This puts periphery scholars at a distinct

disadvantage when publishing in journals of the centre, as the peer-review

process requires writers to reference the most current centre scholarship

(Gibbs, 1995b; Willinsky, 2006). Without access to the current literature of

the centre, periphery scholars are left out of the scholarly conversation and

excluded from full participation in the process of knowledge creation

(Canagarajah, 2002; Holdom, 2005). This creates a situation in which developing

countries have the art, but in a striking parallel to colonial exploitation of

raw materials, it has to be analyzed in the centre to be turned into scholarly

knowledge accepted by the centre (Canagarajah, 2002).

Latin America is in

many ways at the forefront of creating open scholarly knowledge. For example,

Open Access (OA) publishing has been readily adopted in Latin America. Indeed,

the OA model is much more prevalent in Latin American than in most other

regions; a full 51% of online journals in Latin America are open access

(Alperín et al., 2011, 2008). Growing internet connectivity and the historical

lack of visibility of Latin American print journals has meant that OA

e-publishing gives scholars in Latin America new opportunities to disseminate

their research (Holdom, 2005). Several factors have enabled the wide adoption

of OA in Latin America including the lack of an entrenched scholarly publishing

industry and first-hand experience by Latin American scholars with the

consequences of limited access (Alperín et al., 2008). Not only are e-journals

flourishing, but open access repositories, databases where copies of articles

are archived and made freely available, have allowed scholars to make their

work openly available even when they publish in toll access journals (Alperín

et al., 2008; Johnston, 2010).

Aims

The study’s goal was

to determine the availability of centre art journals at Latin American

universities that are practicing open scholarship. The literature review

revealed that Latin American scholars are making their work openly accessible

to global scholars, but do scholars at these universities have access to the

core journals of centre art scholarship?

Methods

The first step was

identifying Latin American universities that are practicing open scholarship.

This study used the OpenDOAR Database to select institutions. OpenDOAR lists

universities with institutional repositories by country. These institutions

have created and support databases where their affiliates can deposit their

scholarly products and have them made openly available, demonstrating

participation in the open access movement. Additionally, the resources and

staff necessary to operate a repository suggest a certain minimum level of

funding. Universities with a singular focus like engineering or medicine were

eliminated as out of scope. Due to language limitations only institutions in

Spanish speaking countries were selected. After excluding institutions that did

not meet the criteria, there were a total of 78 institutions; however, for 18

of these, reliable subscription information could not be located, so the final

sample was 60 university libraries.

The study investigated

access to two art history journals: the

Burlington Magazine and the Art

Bulletin. These two journals were selected because they are core journals

for art history. The Burlington Magazine

is the longest continually published art periodical in English. Published in

the United Kingdom, it set the standard for scholarly art history publications,

cementing its reputation with a string of well-respected editors (Fawcett & Phillpot, 1976). Beginning

publication not long after, the Art

Bulletin rose in prominence to become arguably the most influential art

journal (Fawcett & Phillpot, 1976).

It is published in the United States of America by the College Art Association.

Neither journal focuses exclusively on Latin America; instead the articles,

editorials, letters, and reviews in these journals are key sites of the

scholarly back-and-forth that generates new scholarly knowledge in the centre.

Because the goal was to determine Latin American scholars’ ability to

participate in the broader scholarly conversation going on in centre art

history, these journals were selected specifically because of their importance

to the discipline as a whole, rather than because of a focus on Latin American

art. Selecting journals that solely study Latin American art would have risked

pigeonholing Latin American scholars and suggesting that they are only able to

work on local topics, while centre scholars enjoy the whole purview of global

art to study.

The sixty university

library websites and catalogs were investigated for access to each journal.

Each of the various ways that universities had access to the journal was

recorded. As an additional check to catalog and website searching, an e-mail in

English and Spanish was sent to these sixty libraries, in order to confirm that

availability had not been missed. The responses that were received were then

checked against the information gathered from the websites. We found that the

emails verified the information found on websites and catalogs.

This study has several

limitations. Firstly, it includes only two art history journals and relatively

expensive ones at that. However, these journals represent major loci of

scholarly conversations in art history. Scholars attempting to write art

history that is publishable in centre journals would find themselves

confronting a nearly unbridgeable lacuna in their research without access to

articles from these journals. While this is a limitation, the selected journals

are used as indicators of problematic access to centre art history scholarship

as a whole. Additionally, the study only examines Latin American universities

with institutional repositories. Therefore, it does not necessarily reflect the

situation at all Latin American universities, only those with repositories.

However, if institutions with repositories are outliers, the funding commitment

and know-how that a repository represents suggests that their libraries may be

more well-funded than the average. As the study only looks at these major

universities, it consequently left out smaller, perhaps more art-focused

institutions such as museum libraries. While access at specialty libraries is

certainly an interesting question, a major concern of this study was the ease

and convenience of reading these journals at research universities, where the

majority of scholars are concentrated. While scholars may be willing to make

extraordinary efforts to track down a single key article, these hurdles waste

scholars’ time, and preclude them from keeping up with general trends and

emerging ideas, which are made possible by easy access through one’s

institution.

Results

The results show that

most Latin American scholars at institutions with repositories lack access to

these two major journals of art history. A large percentage of institutions had

no access to either publication. Where there was access it was generally

suboptimal, often only available after an embargo or at the mercy of a

commercial vendor which could drop coverage at any time.

The study found

several ways that libraries provide access to these two journals. They may

subscribe directly to print or electronic editions. Older issues of both

journals are available through a subscription to JSTOR, though not current

issues, as there is an embargo of five years for the Burlington Magazine and the Art

Bulletin in JSTOR. Libraries that subscribe to some EBSCO or ProQuest

full-text packages such as Academic Search Premiere can also get access to the Art Bulletin. However, this access is

unstable, as these content aggregators can drop the full-text access at any

time. Additionally, the extent of back issue access varies among packages, and

none provide full access to the entire back file. There were five kinds of

access for each journal possible at each institution.

- Subscription: A direct subscription to the print

or electronic version of the journal. Considered full access.

- JSTOR: Access through JSTOR to back issues, but

lacking the five most recent years due to the embargo.

- Aggregator: Access via ProQuest and EBSCO to

current issues and varying amounts of back file, but this access is

unstable and unreliable.

- JSTOR and Aggregator: Access to current issues

via an aggregator as well as reliable access to back issues through JSTOR.

Considered full access.

- No Access.

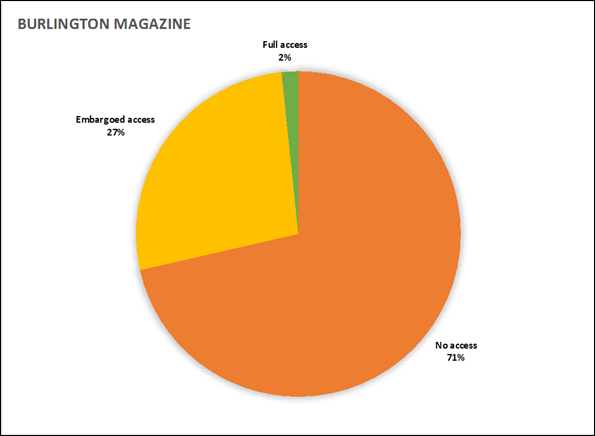

Figure 1

The Burlington Magazine is unavailable at

most Latin American universities.

Figure 2

The Art Bulletin is more accessible, but

much of the access is unreliable.

As shown in figure 1,

only a single institution had access to recent issues of the Burlington Magazine. In a full 72% of

institutions, the Burlington Magazine

was not available at all. Another 27% had access through JSTOR to articles, but

only with a five year embargo.

As shown in figure 2, Art Bulletin was unavailable at 42% of

the institutions, while 58% had access of some kind to recent issues. The

journal’s relative availability is due to its inclusion in the typical package

of full-text journals subscribed to through content aggregators such as EBSCO

and ProQuest. Indeed, only two institutions (3%) had direct subscriptions to

the Art Bulletin. This means that 55%

of institutions had access to recent issues of the Art Bulletin entirely through aggregators. Problematically,

however, access through content aggregators is not stable. EBSCO or ProQuest

could cut Art Bulletin from their

packages or the Art Bulletin could

decide to withdraw, and these institutions would be left with no access to the

journal, not even to back issues. Additionally, for those institutions with

only aggregator subscriptions, there is a lack of access to a substantial

amount of the back file. Some institutions also had subscriptions to JSTOR

(27%) that gives them stable access to back issues. When combined with their

aggregator subscriptions, these institutions, along with those with direct

subscriptions, were considered to have full access to the Art Bulletin. Overall, 30% of institutions had full access to the

Art Bulletin either through subscription or a combination of JSTOR and aggregator

access.

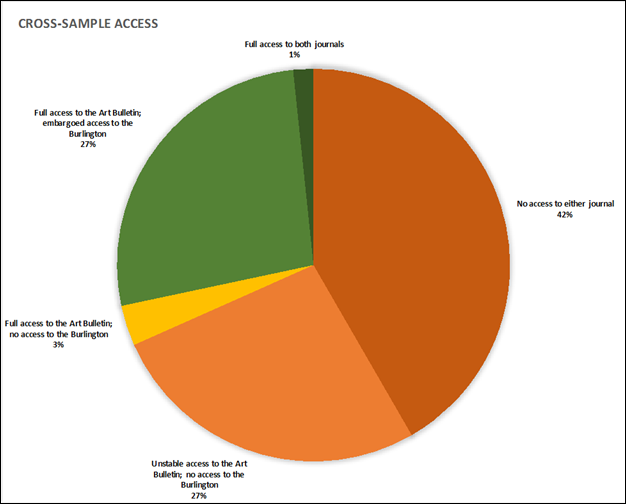

Figure 3 shows a

cross-sample of both journals, in which 42% of institutions had no access to either

journal. A combined 30% had some access to one journal (always the Art Bulletin), either full access (3%)

or unstable access (27%), while having no access to the Burlington Magazine. Only a combined 28% of institutions had some

access to both journals. In this small group that had access to both journals,

only one institution had full access to both journals without an embargo, while

the rest had full access to the Art

Bulletin but only had access to the Burlington

Magazine after a five-year embargo.

Figure 3

The combined picture

of the two journals shows that many institutions lack access to either journal,

while very few institutions have access to both.

Discussion

The results show a

concerning lack of access to these centre-published art history journals at

Latin American universities with institutional repositories. This study found

that even when access does exist it is often delayed by five years. The results

suggest that Latin American scholars at these institutions will have difficulty

reading art history articles published in centre journals in a timely way. As

the literature has shown, limited access to centre journals hinders periphery

scholars’ ability to publish in these same journals because of the difficulty

of staying up-to-date on the most recent centre theory (Gibbs, 1995b;

Willinsky, 2006). Therefore, lack of access limits periphery scholars’ ability

to fully participate in centre discourse. They will be challenged to

communicate their theories, ideas, and interpretations to centre scholars, and

they will have difficulty debating the work of centre scholars, even when that

scholarship is on the art of Latin America. Lack of access thus helps to

perpetuate a colonial system of art history knowledge creation in which new

knowledge is created and given authority by those in the centre, and where the

art and ideas of Latin America only enters the scholarly discourse after being

analyzed by centre scholars.

Due to barriers to

participation in centre scholarship, the ideas and theories of these periphery

scholars are likely to be published in local journals. These publications have

a high chance of remaining unseen by centre scholars. Previous studies have

shown that much of the art history published in Latin America, though often

made available through open access, is difficult to find through conventional

research methods (Alperín et al., 2011; Evans, Thompson, & Watkins,

2011; Holdom, 2005). As a result of

inadequate information access, there is breakdown in global scholarly

communication, where art history ideas are not being transmitted between centre

and periphery. The theory and analyses created in both the periphery and the

centre remain in separate spheres, rather than becoming engaged in meaningful

dialogue and productively building on one another. Thus the scholarly

conversation in art history is impoverished, losing key voices while privileging

those scholars with greater information resources.

Solving the access

problem for these Latin American universities will require a change in

traditional systems of knowledge distribution in the discipline. Simply having

Latin American institutions increase their journal subscriptions is not a

viable solution. When many libraries are cancelling subscriptions, and the

rising cost of existing subscriptions exceeds inflation, this is simply

untenable (Hoskins & Stilwell, 2011; Spencer

& Millson-Martula, 2006). Centre scholars should question whether

only publishing in a scholarly journal, even (and perhaps particularly) top

tier toll-access journals, adequately disseminates their work to the global

scholarly community. Open access publishing is a well-established alternative

model in which access is free for the reader. Open access has already been

adopted by many Latin American scholars: all the institutions in this study

already have institutional repositories, and open access journals are far more

popular in Latin America than in the United States. If centre scholars were to

increase their adoption of open access practices, their scholarship would

become far more accessible and easily available to Latin American scholars.

Importantly this would start to alleviate access problems in Latin America and

facilitate global conversations.

Conclusion

Access to scholarship

is often overlooked in calls for a more global art history. But far from being

a secondary concern, it is a key requirement for scholarly conversations that

truly integrate global perspectives and move away from an inherently limited

centre-out model of scholarship. More openly available scholarship is necessary

if global voices are to participate in centre art history, and if centre and periphery

discourses are to be joined into a single, richer discussion. It seems that

traditional models for access to and dissemination of scholarship are not up to

this task. The evidence of substandard access to centre art history scholarship

suggests there is further work to be done investigating access to information

in the periphery, as well as the effect of this limited access on the work of

scholars in a range of other disciplines. It is this author’s sincere hope that

this work will catalyze and build towards sustainable solutions, as well as

motivate individual scholars to help create a more global discourse by moving

toward open access scholarship.

Acknowledgements

The author wishes to

thank his research assistant, Amanda Saracho, whose language skills and time spent

combing library websites were key to the writing of this article.

References

Alperín, J. P., Fischman, G. E., &

Willinsky, J. (2011). Scholarly communication strategies in Latin America’s

research-intensive universities. Educación Superior Y Sociedad, 16(2).

Retrieved from http://pkp.sfu.ca/files/iesalc_final.pdf

Alperín, J. P., Fischman, G., & Willinsky,

J. (2008). Open access and scholarly publishing in Latin America: Ten flavours

and a few reflections. Liinc Em Revista, 4(2).

dx.doi.org/10.18617/liinc.v4i2.269

Arunachalam, S. (2003). Information for

research in developing countries — information technology, a friend or foe? The

International Information & Library Review, 35(2–4), 133–147.

Bonaccorso, E., Bozhankova, R., Cadena, C.,

Čapská, V., Czerniewicz, L., Emmett, A., … Tykarski, P. (2014). Bottlenecks in

the open-access system: Voices from around the globe. Journal of

Librarianship and Scholarly Communication, 2(2).

dx.doi.org/10.7710/2162-3309.1126

Canagarajah, A. S. (2002). A geopolitics of

academic writing. Pittsburgh, PA: University of Pittsburgh Press.

Davison, R., Harris, R., Licker, P., &

Shoib, G. (2005). Open access e-journals: Creating sustainable value in

developing countries. PACIS 2005 Proceedings, 21. Retrieved from http://aisel.aisnet.org/pacis2005/21/

Evans, S., Thompson, H., & Watkins, A.

(2011). Discovering open access art history: A comparative study of the

indexing of open access art journals. The Serials Librarian, 61(2),

168–188.

Fawcett, T., & Phillpot, C. (Eds.).

(1976). The art press: Two centuries of art magazines. London: The Art

Book Company.

Gibbs, W. W. (1995a). Information have-nots. Scientific

American, 272(5), 12b–14.

https://doi.org/10.1038/scientificamerican0595-12

Gibbs, W. W. (1995b). Lost science in the

third world. Scientific American, 273(2), 92–99. https://doi.org/10.1038/scientificamerican0895-92

Gómez, N., & Bongiovani, P. C. (2012).

Open access and A2K: Collaborative experiences in Latin America. In J. Lau, A.

M. Tammaro, & T. J. D. Bothma (Eds.), Libraries driving access to

knowledge (pp. 343–371). Berlin: De Gruyter Saur.

Holdom, S. (2005). E-journal proliferation in

emerging economies: The case of Latin America. Literary & Linguistic

Computing, 20(3), 351–365. https://doi.org/10.1093/llc/fqi033

Hoskins, R., & Stilwell, C. (2011).

Library funding and journal cancellations in South African university

libraries. South African Journal of Libraries and Information Science, 77(1),

51–63. http://dx.doi.org/10.7553/77-1-66

Johnston, M. (2010). Changing the paradigm:

The role of self-archiving and institutional repositories in facilitating

global open access to knowledge. Access to Knowledge: A Course Journal, 2(1).

Retrieved from http://ojs.stanford.edu/ojs/index.php/a2k/article/view/429

Spencer, J. S., & Millson-Martula, C.

(2006). Serials cancellations in college and small university libraries. The

Serials Librarian, 49(4), 135–155. https://doi.org/10.1300/J123v49n04_10

Teferra, D. (2004). Striving at the periphery,

craving for the centre: The realm of African scholarly communication in the

digital age. Journal of Scholarly Publishing, 35(3), 159–171.

Terra Figari, L. I. (2007). Diseminación del

Conocimiento Académico en América Latina. In Anuario de Antropologia Social

y Cultural en Uruguay (pp. 193–204).

Montevideo, Uruguay: Editorial Nordan. Retrieved from http://www.unesco.org.uy/shs/fileadmin/templates/shs/archivos/anuario2007/articulo_15.pdf

Willinsky, J. (2006). The access principle:

The case for open access to research and scholarship. Cambridge, MA: MIT

Press.