Research Article

E-Preferred Approval Books at the University of

Manitoba: A Comparison of Print and Ebook Usage

Jan C Horner

Senior Scholar, Collections Management

University of Manitoba Libraries

Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada

Email: j.horner@umanitoba.ca

Received: 23 Aug. 2016 Accepted: 13 Feb. 2017

![]() 2017 Horner. This is an Open Access article

distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

2017 Horner. This is an Open Access article

distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

Abstract

Objective – To compare the usage of print and ebooks received on University of

Manitoba’s e-preferred YBP approval plan as well as to examine cost per use for

the approval print books and ebooks.

Methods – Usage data was compiled for books received on approval in 2012/2013 to

December 31, 2014. Counter reports were used to determine use and non-use of

ebooks, while vendor reports from EBL and ebrary were used for the cost per use

analysis. Print usage information was drawn from SIRSI and then ALMA when UML

switched systems at the beginning of 2014.

Results – Ebooks received more use than p-books overall, but when examined by

subject discipline, significant differences could not be found for the “STM”

and “Other” categories. With ebooks, university press books tended to be used

more than those from other publishers, but the same result was not found for

print books. Ebrary ebooks tended to be used more often than EBL, EBSCO, and

Wiley ebooks, and single-licence books tended to be somewhat more used than

multi-user ones. Cost-per-use data was much lower for print books, though the

comparison did not look at staffing costs for each medium.

Conclusions – This study finds that of approval books matching the same profile,

ebooks are used more, but print books receive more substantial use. Both

formats are needed in a library’s collection. Future comparisons of cost per

use should take into account hidden labour costs associated with each medium.

Usage studies provide evidence for librarians refining approval plan profiles

and for budget managers considering changes to monographic acquisition methods

and allocations.

Introduction

Libraries

are changing the way they acquire monographs. Demand-driven and publisher

front-list acquisition options are competing with traditional methods of firm

ordering and approval plan delivery.1 Approval plans are intended to

save staff time and can operate despite staff absences or changes. But

libraries are looking more critically at approval plans since purchasing a

publisher’s front list or using demand-driven acquisition can also save staff

time.

This study

looks at the performance of the YBP e-preferred approval plan at the University

of Manitoba Libraries (UML). UML is an ARL and CARL member with an enrollment

of approximately 30,000 and faculties of Agricultural & Food Sciences,

Architecture, Arts, Engineering, Health Sciences, Law, Management, Music, and

Sciences. It is the major research library for the province.

UML is

facing budget challenges similar to those at other ARL libraries where

monograph budget funds have decreased on average 4% over the last three years

reported. UML’s monograph budget has decreased 8.5%.2 During the

same period the financial commitment to demand-driven ebook acquisitions has

remained steady and UML has purchased the Springer ebook collection and

subscribed to other ebook collections (e.g. EBSCO, Knovel). Budget challenges

were thus a strong motive to review the performance of UML’s approval plan.

Literature Review

This study

is quantitative; therefore, qualitative studies of ebook versus print use,

although of interest and value, were not included in the review.

Ebook v

Print Comparisons

Most

quantitative studies of ebook and print monograph usage have examined the same

titles in both formats. In addition,

most of the early studies (e.g., Littman & Connaway, 2004) looked at

Netlibrary titles as a basis of comparison with print. After 16 months of use

the Littman & Connaway study at Duke University found 40% of the ebook

versions had been used and 36% of the print (p. 259).

Kimball, Ives,

and Jackson, in their study (2009), identified 4,288 Netlibrary books in the

sciences that were also available in print. Although the ebooks were used more

times per book, 24% of the ebooks were accessed while 23% of the print versions

circulated (p. 23-24).

More

recently Levine-Clark & Brown (2013) compared the use of Duke University

Press titles online and in print published between 2009 and 2012. A greater

number of print titles had been acquired before the ebook version, but there

were 1,150 titles held in both formats. Of those titles, 54% of the print

circulated and 39% of the ebooks had been used, leading the authors to conclude

that when both formats were available, users preferred the print (slide 25).

Goodwin (2014) looked at the 2011 collection from Duke University Press, 285

ebooks and 275 print (10 matching print titles had not been received by the

study start). Usage was counted to October 2013 (two years, five months) and

resulted in 73% of the ebooks being used and only 29% of the print, although

only 12% of the ebooks received “substantive use.”

A Kent

State study (Downey et al., 2014) did not compare the same titles in print and

ebook. Rather it looked at the performance of 20,000 of the most recently

acquired print books (up to January 2012) added between July 2009 and January

1, 2012 in relation to 20,018 discovery records which were loaded in their

catalogue for a patron-driven acquisition (PDA) project that ran January to

December 2012 using ebrary ebooks. By the end of 2012, 8% of the books in the

PDA discovery pool had been used (p. 148) with only 2% triggering a purchase

(p. 154), but a relatively high number (62.5 %) (p. 149) of the purchased print

books had circulated.

Ebook Usage

Levine-Clark

(2014), working with major ebook vendors EBL and ebrary, examined data for

about 625,000 ebooks across roughly 800 academic libraries. This study could

not be used to predict rates of use in a single library, since the titles had a

massive pool of potential readers. It found that usage of Social Science ebooks

was higher than that for Humanities and Science, Technology & Medicine

(STM) titles in terms of percentage of titles used and average amount of use

(slides 31-36). Patrons spent more time in Humanities ebooks per online session

than for ebooks in the other disciplines. STM ebooks involved more downloading.

EBL and Ebrary titles were examined separately. In general Humanities ebooks

were used more than STM titles on ebrary, and STM titles were used more than

Humanities ones on EBL (slides 31-32).

Comparisons

of Ebook Types of Acquisition

Many

authors have published reports on patron-driven or demand-driven acquisition

(PDA, DDA) programs at academic libraries. However, because PDAs/DDAs count

usage of never purchased titles as well, they are not relevant to the present

study of titles acquired by approval in print and electronic format.

Carrico et

al. (2015, pp. 106-107) compared the usage of ebooks acquired in large

publisher packages with those that were firm-ordered by librarians. In terms of

the packages, 50% were used compared to 52% of the firm-ordered titles. This

figure was somewhat skewed by the use of the medical titles in which 63% of the

package titles and 84% of the firm-ordered titles were used. For the

Humanities/Social Sciences, package titles and firm orders were used 47% and

45% respectively. For Science & Technology package titles and firm orders

were used 49% and 57% respectively.

Print Usage

and Substantive Use of Ebooks

A number of

studies have shown that the percentage of print collections that circulate is

low. Rose-Wiles (2013) examined the circulation for 2005 to 2009 of the entire

collection of 443,577 print books at Seton Hall University and found 21.5% had

circulated (p. 137). However, only 17.7% had been published in the 2000s. She

examined the subset of science books published since 2000 and found 34.5%

circulated 2005 to 2009 (p. 141). A

Cornell University study (2010, p. 2) looked at the circulation of its collection

published between 1990 and 2010 (1.6 million titles) and found that 45% had

circulated.

A 2009

study (Alan et al.) looked at the usage of print titles acquired through

approval plans, examining books received at University of Illinois at

Urbana-Champaign (UIUC) and Pennsylvania State University (Penn State) July

2004 to June 2005 where usage was gathered from July 2004 to March 2007. It

found that 69% of Penn State’s and 60% of UIUC’s approval books had circulated

at least once (p. 70). It was suggested that the higher percentage of use at Penn

State was based on the larger user population, 98,000 versus 45,000 at UIUC. No

breakdown of use/non-use was provided by subject.

Most

studies and guidelines (NISO, 2014, p.34) have exercised caution in drawing

conclusions about the higher number of uses/transactions/sessions of ebooks in

comparison with print usage. Many libraries do not capture in-house use of

their print collections, and some ebook accesses may be equivalent to the act

of taking a book off the shelf, glancing through it, and then replacing it.

Some

authors have looked at measures of substantive ebook use as a means of

comparison with print circulation. Rose-Wiles used viewing of 10+ pages in an

ebook as equivalent to a print check-out (p. 146). Goodwin used viewing 11+

pages as a measure of substantive use (p. 103). Ahmad & Brogan (2012, p.

198) in their case study of EBL ebooks usage, set the standard of more than 9

minutes spent in a book as an indication of reading, since the EBL platform

uses that time to differentiate reading from browsing. In their study 29.12% of

transactions were spent in reading under this definition and 70.88% in

browsing.

None of the

studies mentioned downloading as an equivalent to print check-outs. However,

download could provide a more equivalent measure of comparison to the print

check-out. Some effort is required to download the book. Though shorter than

most print loan periods, a patron can use the ebook offline for one to three

days. With both ebook downloads and print check-outs, there is no way of

knowing how much a book is used while ‘out’ or in ‘offline’ mode.

Aims

This study

assumes that a comparison of print book (p-book) and ebook usage is possible,

especially when substantive use of ebooks is compared with print checkouts.

Given that

the YBP approval plan will deliver a greater proportion of ebooks over time,

this analysis attempts to answer these questions:

- Are approval ebooks being used

at an equal or higher rate than print approval books?

- Is the usage or non-usage of

approval ebooks and print books affected by their broad subject

discipline? Is the usage/non-usage the same or different for the two

media?

- Are university press books

used more than non-university press books, and is usage the same for print

and ebook?

- Did the vendor or type of

license affect the usage of ebooks?

- What is the cost-per-use of an

approval ebook and the cost-per checkout for a print approval book?

Method

Most

comparisons of the performance of p-books and ebooks have been done comparing

the same titles in both formats. Unless an analysis looks at the same titles

purchased at the same time in the two formats, it is challenging to compare

performance over a similar time period. Differing time periods for access may

have affected the results of earlier studies (Levine-Clark & Brown, 2013,

slide 3; Downey et al., 2014, p.145).

Although

the titles are different in the UML comparison of approval books, approval

books, no matter what format, are purchased over the same time period, match

the same subject profile, and come from a similar set of publishers with

similar publication dates. There is a wide variety of ebook platforms on the

market, but the UML ebooks come on four platforms prescribed by the approval

profiles: EBL, ebrary, EBSCO, and Wiley.

In

2012/2013, all subject profiles within the YBP approval plan were converted to

e-preferred with the exception of pharmacy. The e-preferred mode meant that if

an ebook were published within eight weeks of the print version, an ebook would

be received by UML. In 2012/13, 35% of

the approval receipts were ebooks. Usage of the approval books received in

2012/13 was counted to December 31, 2014, so both p- and ebooks were available

for use between 20 and 32 months.

Table 1

Overall

Comparisons of Print- and Ebook Usage

|

|

No. of titles |

No. used |

% used |

|

Print Books |

5,237 |

2,003 |

38% |

|

Ebooks |

1,855 |

872 |

47% |

|

P-Value

two-sided |

proportion

of usage different between p- & ebooks |

0.0011 |

|

|

P-Value

one-sided |

proportion of usage greater for

ebooks |

0.00056 |

|

|

Note: P = <

0.05 |

|

|

|

Source of

data

Lists of

ebooks and p-books received on approval were generated from SIRSI’s Director’s

Station. Some call number and publisher data was retrieved from YBP’s GOBI

database.

While the

Counter Book Report 2 was only available from ebrary, only the Counter Book

Report 1 was produced for EBSCO, Wiley, and EBL ebooks. The Counter Book Report

2 records the number of uses of a section or sections of a book by month and

title, whereas the Counter Book Report 1 counts only the uses of a title by

month, without considering the use of chapters within it. The Counter 2 Book

Report will therefore yield higher uses per title since it counts every section

or chapter of a single title as a separate use, whether they were viewed in

separate sessions or not. Because of this discrepancy, this study does not

attempt to measure rates of use based on Counter reports, only use and non-use.

More detailed information about use was obtained from vendor reports for EBL

and ebrary ebooks for cost per use analysis; EBSCO and Wiley did not provide

detailed information for their ebooks so were not included. Cost per use was

calculated per book and then averaged, rather than the collection cost being

divided by overall use as in other studies (Bucknell, 2010, p. 133; Bucknell,

2012, p. 53).

For

p-books, circulation data was derived from SIRSI to the end of 2013, and then

when UML changed systems, from ALMA for 2014. UML does not have consistent data

on in-house use of its print collections. Therefore usage of print books was

based simply on number of check-outs.

2012/2013

approval results

In this

fiscal year UML received 5,237 p-books and 1,855 ebooks on approval. Of those,

38% of the p-books (2,003) circulated and 47% of the ebooks (872) were used. A

Pearson’s chi-square test for comparing two proportions showed that there was

sufficient statistical evidence to conclude the usage of print and ebooks was

different and that ebook use was greater than print.

A further

analysis was done by broad subject discipline based on the following LC call

number ranges, using the same subject breakdown as Levine-Clark (2014, slide

30).

·

Arts &

Humanities: B-BD,

BH-BX,

C-F,

M-P

·

Social Sciences: BF,

H-L, U-V

·

Science, Technology

& Medicine

(STM): Q-T

Use of

ebooks by broad discipline

This

analysis indicates that usage of ebooks in the broad disciplines is remarkably

similar.

Table 2

Ebook Usage

by Broad Subject Discipline

|

|

No. ebooks |

No. used |

% used |

Proportion of total ebooks |

Proportion of total uses |

|

Arts & Humanities |

635 |

300 |

47% |

34.2% |

34.4% |

|

Social Sciences |

669 |

306 |

46% |

36% |

35% |

|

Science, Technology &

Medicine (STM) |

494 |

236 |

48% |

26.6% |

27.2% |

|

Other |

57 |

30 |

53% |

3.1% |

3.4% |

|

Total |

1,855 |

872 |

47% |

|

|

Use of

p-books by broad discipline

UML

received many more “Arts & Humanities” print books through the approval

plan, but their usage was lower, compared to the size of the collection, while

use of “STM” print books appeared to be higher relative to the size of its

collection.

The results

of the chi-square tests (Table 4 below) provided sufficient statistical

evidence to find that usage of print and ebooks was different and higher for

ebooks in the “Arts & Humanities” and “Social Sciences” categories.

However, there was not statistical evidence to claim the same for the “STM” and

“Other” categories.

Table 3

Print Book Usage

by Broad Subject Discipline

|

|

No. p-books |

No. used |

% used |

Proportion of total p-books |

Proportion of total uses |

|

Arts & Humanities |

2,263 |

807 |

36% |

43% |

40% |

|

Social Sciences |

1,740 |

657 |

38% |

33% |

33% |

|

Science, Technology &

Medicine (STM) |

1,063 |

469 |

44% |

21% |

24% |

|

Other |

171 |

70 |

41% |

3% |

3% |

|

Total |

5,237 |

2003 |

38% |

|

|

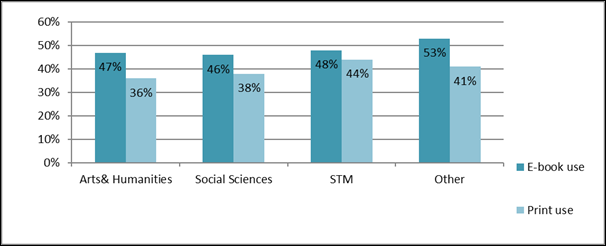

Figure 1

Comparison

of print and ebook usage by broad subject.

Table 4

P- and Ebook

Usage Comparison Chi-square Test

|

Subject |

Proportion of Usage Ebook |

Proportion of Usage P-book |

P-Value two-sided |

P-Value one-sided |

Decision |

|

Arts & Humanities |

0.472 |

0.357 |

<0.0001 |

<0.0001 |

Significant difference |

|

Social Sciences |

0.457 |

0.379 |

0.0004 |

0.0002 |

Significant

difference |

|

STM |

0.478 |

0.439 |

0.1474 |

0.07372 |

Insufficient stat. evidence |

|

Other |

0.526 |

0.41 |

0.1262 |

0.06309 |

Insufficient

stat. evidence |

|

Note: P = <

0.05 |

|||||

Ebooks use

by type of publisher

For ebooks,

usage of books published by university presses was higher, especially

considering use relative to the collection size.

Table 5

Ebook Usage

by Type of Publisher

|

|

No. of ebooks |

No. used |

% used |

Proportion of total ebooks |

Proportion of total uses |

|

University presses |

878 |

449 |

51% |

47% |

51% |

|

Other publishers |

977 |

423 |

43% |

53% |

49% |

|

Total |

1,855 |

872 |

47% |

|

|

|

P-Value

two-sided |

|

|

0.0007 |

Proportion used is different

between university presses & other publishers |

|

|

P-Value one-sided |

|

|

0.0004 |

Proportion

used is greater for university presses than other publishers |

|

|

Note: P = <

0.05 |

|

|

|

|

|

P-books use

by type of publisher

In

comparison with ebooks, usage of print books from university presses did not

appear different from that of print books from trade or other publishers.

Proportionally UML received more university press books (47%) as ebooks while

university press books accounted for only 39% of the print titles received.

Table 6

Print Book Usage

by Type of Publisher

|

|

No. of p-books |

No. used |

% used |

Proportion of total p-books |

Proportion of total uses |

|

University presses |

2,055 |

788 |

38% |

39% |

39% |

|

Other publishers |

3,182 |

1,215 |

38% |

61% |

61% |

|

Total |

5,237 |

2,003 |

38% |

|

|

|

P-Value

two-sided |

|

|

0.4205 |

Proportion used is not

significantly different between publisher type |

|

|

P-Value

one-sided |

|

|

0.2103 |

Proportion

used is not significantly greater |

|

|

Note: P = <

0.05 |

|

|

|

|

|

Ebooks use

by vendor platform

The

analysis by vendor platform suggested that ebrary was the preferred platform.

Table 7

Ebook Usage

by Vendor Platform

|

|

No. of ebooks |

No. used |

% used |

Proportion of total ebooks |

Proportion of total uses |

|

EBL |

867 |

371 |

43% |

47% |

43% |

|

ebrary |

820 |

434 |

53% |

44% |

50% |

|

EBSCO |

77 |

28 |

36% |

4% |

3% |

|

Wiley |

91 |

39 |

43% |

5% |

4% |

|

Total |

1,855 |

872 |

47% |

|

|

|

P-Value

two-sided |

|

|

<0.0001 |

Proportion of usage differs

significantly among vendors |

|

|

Note: P = <

0.05 |

|

|

|

|

|

Table 8

Ebook Usage

by Type of License

|

|

No. of

ebooks |

No. used |

% used |

Proportion

of total ebooks |

Proportion

of total uses |

|

Single

user (ebrary) |

483 |

250 |

52% |

26% |

29% |

|

1

user (EBSCO) |

77 |

28 |

36% |

5% |

4% |

|

Non-linear

lending (EBL) |

863 |

368 |

43% |

46% |

52% |

|

Multi-user

(EBL) |

4 |

3 |

75% |

.02% |

.03% |

|

Multi-user

(Wiley) |

91 |

39 |

43% |

5% |

4% |

|

Multi-user

(ebrary) |

337 |

184 |

55% |

18% |

21% |

|

Total |

1,855 |

872 |

47% |

|

|

|

P-Value

two-sided |

|

|

<0.0001 |

Proportion of usage differs significantly

among the different vendor licenses |

|

|

Note: P =

< 0.05 |

|

|

|

|

|

Figure 2

Comparison

of usage of single user and multi-user licences.

Ebooks use

by license

Ebrary

ebooks seemed to receive higher usage independent of license type.

When

results were separated into single-user and multi-user licenses, single-user

licensed books were used somewhat more.

Substantive

use of EBL and ebrary ebooks

Both EBL

and ebrary provided detailed reports on usage, allowing a better comparison

between p-books and ebooks. The two providers accounted for 91% of the ebooks

received on approval in 2012/2013. Wiley and EBSCO ebooks were excluded from

cost and cost-per-use calculations. For the purpose of this study, substantive

use was determined to have occurred either when a title had been downloaded at

least once, or when 11+ pages had been viewed or read. The level of substantive

use of ebooks (32%) is lower than the overall mean usage (38%) of approval

print books based on check-outs.

Table 9

Substantive

Use of EBL and Ebrary Ebooks

|

|

No. ebooks |

No. used |

No. of sessions/ transactions |

Mean session per book |

Mode session per book |

No. of ebooks down- loaded |

No. of ebooks with substantive

use |

% ebooks with substantive use |

|

EBL |

868 |

371 |

1,519 |

4 |

2 |

149 |

309 |

35.6% |

|

ebrary |

819 |

434 |

1,610 |

3.7 |

2 |

81 |

238 |

29% |

|

Total |

1,687 |

805 |

|

|

|

|

547 |

32% |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Mean costs

for EBL and ebrary ebooks

The overall

cost of the EBL collections is slightly higher than that of ebrary’s because it

has about 40% more “STM” books, which tend to be more expensive. In addition,

pricing of an EBL non-linear lending ebook tends to be higher than a

single-user title from ebrary.

A further

analysis was done by broad discipline on the two platforms. The results showed

that in general the EBL books were more expensive than ebrary’s in all disciplines

except “Social Sciences”.

Table 10

Mean cost

of EBL and Ebrary Ebooks

|

|

No. of ebooks |

Cost of all ebooks |

Mean cost of all ebooks |

No. of ebooks used |

Cost of ebooks used |

Mean cost of ebooks used |

|

EBL |

868 |

$87,737* |

$101 |

371 |

$36,826 |

$99 |

|

ebrary |

819 |

$70,556 |

$86 |

434 |

$36,063 |

$83 |

|

Total |

1,687 |

$158,293 |

$94 |

805 |

$72,889 |

$91 |

|

* all

costs given are in Canadian dollars |

||||||

Table 11A

EBL Ebooks Mean

Cost by Discipline

|

|

No. of ebooks |

Cost of all e- books |

Mean cost of all ebooks |

No. of ebooks used |

Cost of ebooks used |

Mean cost of ebooks used |

|

Arts & Humanities |

284 |

$25,168 |

$88 |

116 |

$10,792 |

$93 |

|

Social Sciences |

313 |

$24,801 |

$79 |

123 |

$9,726 |

$79 |

|

STM |

245 |

$31,800 |

$130 |

119 |

$14,863 |

$125 |

|

Other |

26 |

$3,043 |

$117 |

13 |

$1,446 |

$111 |

|

Total |

868 |

$84,812 |

$98 |

371 |

$36,827 |

$99 |

Table 11B

Ebrary Ebooks

Mean Cost by Discipline

|

|

No. of ebooks |

Cost of all ebooks |

Mean cost of all ebooks |

No. of ebooks used |

Cost of ebooks used |

Mean cost of ebooks used |

|

Arts & Humanities |

322 |

$24,426 |

$76 |

173 |

$12,944 |

$75 |

|

Social Sciences |

322 |

$27,574 |

$86 |

174 |

$15,062 |

$87 |

|

STM |

148 |

$17,059 |

$115 |

70 |

$7,133 |

$102 |

|

Other |

27 |

$2,310 |

$86 |

17 |

$1499 |

$88 |

|

Total |

819 |

$71,369 |

$87 |

434 |

$36,638 |

$84 |

Mean Print

Book Costs

The mean

purchase price of all EBL and ebrary ebooks ($94) is much higher than the mean

cost of all print books ($55).

A further

breakdown of this information was done by broad discipline.

Table 12

Mean Cost

of Print Books

|

No. of p-books |

Cost of all p-books |

Mean cost all |

No. of p-books used |

Cost of p-books used |

Mean cost p-books used |

|

5,237 |

$289,672 |

$55 |

2,003 |

$112,318 |

$56 |

Table 13

Mean Cost

of Print Books by Discipline

|

|

No. of p- books |

Cost. of all p-books |

Mean cost all p- books |

No. of p- books used |

Cost of p- books used |

Mean cost (p- books used) |

|

Arts & Humanities |

2,263 |

$109,462 |

$48 |

807 |

$39,735 |

$49 |

|

Social Sciences |

1,740 |

$90,654 |

$52 |

657 |

$33,383 |

$51 |

|

STM |

1,063 |

$79,681 |

$75 |

469 |

$34,774 |

$74 |

|

Other |

171 |

$9,875 |

$58 |

70 |

$4,426 |

$63 |

|

Total |

5,237 |

$289,672 |

$55 |

2003 |

$112,318 |

$56 |

Cost per

Use Comparison

Cost per

use for EBL ebooks, ebrary ebooks, and print books ($57, $51, and $34) was

about 40% less than the mean purchase cost per book ($101, $86, and $56

respectively).

The

cost-per-use data has a non-normal or right-skewed distribution for p- and

ebooks and for all disciplines. Therefore, the nonparametric Kruskal-Wallis

test was used to determine where cost-per-use differs among the three

groups: p-books, EBL ebooks, and ebrary ebooks.

As an

alternative strategy, the square-root transformation was applied to the

cost-per-use figures in all groups in order to reduce the right-skewedness in

the data. A t-test (to compare two groups at a time) and the ANOVA (to compare

all three groups) were conducted on the transformed data and the results were

compared with those from the Kruskal-Wallis test. The reported conclusion is based on the

Kruskal-Wallis test.

EBL and

ebrary ebooks are not significantly different in terms of their

cost-per-use. The mean cost per use is

definitely lower for print books with the exception of books in the “Other”

discipline, where the small sample size fails to lead to a conclusion.