Research Article

Digging in the Mines: Mining Course Syllabi in Search

of the Library

Keven M. Jeffery

Digital Technologies

Librarian

San Diego State University

Library

San Diego, California,

United States of America

Email: kjeffery@mail.sdsu.edu

Kathryn M. Houk

Health & Life Sciences

Librarian

San Diego State University

Library

San Diego, California,

United States of America

Email: khouk@mail.sdsu.edu

Jordan M. Nielsen

Entrepreneurship, Marketing

& Business Data Librarian

San Diego State University

Library

San Diego, California,

United States of America

Email: jnielsen@mail.sdsu.edu

Jenny M. Wong-Welch

STEM Librarian

San Diego State University

Library

San Diego California, United

States of America

Email: jwongwelch@mail.sdsu.edu

Received: 2 Sept. 2016 Accepted:

2 Jan. 2017

![]() 2017 Jeffery, Houk, Nielsen, and Wong-Welch. This

is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

2017 Jeffery, Houk, Nielsen, and Wong-Welch. This

is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

Abstract

Objective - The purpose of

this study was to analyze a syllabus collection at a large, public university

to identify how the university’s library was represented within the syllabi.

Specifically, this study was conducted to see which library spaces, resources,

and people were included in course syllabi and to identify possible

opportunities for library engagement.

Methods - A text

analysis software called QDA Miner was used to search using keywords and

analyze 1,226 syllabi across eight colleges at both the undergraduate and

graduate levels from the Fall 2014 semester.

Results - Of the 1,226

syllabi analyzed, 665 did not mention the library’s services, spaces, or

resources nor did they mention projects requiring research. Of the remaining

561, the text analysis revealed that the highest relevant keyword matches were

related to Citation Management (286), Resource Intensive Projects (262), and

Library Spaces (251). Relationships between categories were mapped using

Sorensen’s coefficient of similarity. Library Space and Library Resources

(coefficient =.500) and Library Space and Library Services (coefficient-=.457)

were most likely to appear in the same syllabi, with Citation Management and

Resource Intensive Projects (coefficient=.445) the next most likely to

co-occur.

Conclusion - The text analysis proved

to be effective at identifying how and where the library was mentioned in

course syllabi. This study revealed instructional and research engagement

opportunities for the library’s liaisons, and it revealed the ways in which the

library’s space was presented to students. Additionally, the faculty’s research

expectations for students in their disciplines were better understood.

Introduction

Librarians have

long seen syllabi as a valuable way to gauge how effectively library services

have been integrated into the curriculum. In 2015, the San Diego State

University Library leveraged a campus syllabus collection to do a broad

analysis of how effectively the library was integrating itself into the

curriculum. The San Diego State University (SDSU) Syllabus Collection was

initiated after a 2011 request from the student government for syllabi to be

made available in digital format before the deadline for course registration.

Students were interested in having access to the course requirements,

especially factors like assignments, fieldwork, or required travel that may not

be available in the course catalog description. At the time of the request,

syllabi were mandated by the University Senate to be made available only in

print from department offices. The documents were therefore not easily available

to students who might be registering for classes remotely.

Even though the

primary goal for creating an open and accessible syllabus database was to

provide easier access to course information for students, other potential uses

for the Syllabus Collection have emerged. In addition to being an open syllabus

repository, it also represents a storehouse of data about courses, faculty, and

students at SDSU. In 2015, four librarians in the university’s library mined

the Syllabus Collection to discover how the library was being referenced and

used at the University.

Creating the Syllabus

Collection

A working group

led by the Dean of the Division of Undergraduate Studies identified the library

as a partner on the project due to its having the experience and resources to

manage existing collections of university documents, such as digital theses and

course calendars. The library offered to support the project using a DSpace

instance, the same software used by the library for other campus publications.

As of summer 2015, 90% of academic departments were participating at some level

in the Syllabus Collection, and the collection had surpassed 8,500 documents.

From June 2014 through May 2015, over 1 million syllabi had been downloaded

from the database suggesting the collection has fulfilled the original goal of

providing access to students and those interested in the University course

offerings.

Issues like

intellectual property were relatively easily overcome with the option to use a

course information template instead of the syllabus, but challenges remain.

Even though the campus supports the database, there is no real incentive for

participating, so gaining participation from the last 10% of departments may be

a challenge. While uploading documents is not a hard task for administrative

staff, taking approximately one minute per document, it is sometimes still a

challenge obtaining the syllabi from the teaching faculty. There is a suggested

metadata standard, but there is no enforcement of the standard for the

collection. As section codes are not often included, it is not easy to connect

the syllabus in DSpace to the course calendar to accurately determine the level

of participation.

Literature Review

Prior to

beginning the analysis, a literature search was undertaken using databases

specific to library science, such as Library

Literature & Information Science Index and Library, Information Science & Technology Abstracts, along with

more general subject databases, such as EBSCO

Academic Search Premier and ProQuest

Research Library, as well as the ProQuest

Summon discovery tool. The authors performed independent searches for

articles dealing broadly with syllabi analysis and decided as a group which

articles were appropriate to the project. Most of the studies examined, out of

necessity, looked at small samples of documents that could be obtained directly

from faculty or class sites available on the web. These analyses have been

conducted in a variety of ways, including by random sampling, by targeting

specific student populations/courses, and by focusing on specific degree or

major programs.

Syllabi

Analyses Involving Random Samples

Rambler (1982)

identified a random sample of 162 courses from the Pennsylvania State

University Winter 1979 course schedule and collected syllabi and course

documents directly from faculty. She then rated these according to a

three-point scale for library usage, finding that 63% of the courses required

no library use (p. 156) and that library use increased with class level.

Rambler found that only 8% of the courses analyzed made heavy use of the

library (pp. 158-159). Smith, Doversberger, Jones, Parker, & Pietraszewski

(2012) looked at a similarly sized sample, first identifying the 5,173 course

sections offered in spring 2009 by the University of Notre Dame. They then

eliminated graduate courses, laboratory sections, and directed research

classes. They also eliminated syllabi from sections known to have a library

component. Of the remaining 1,496 sections, they selected a random sample of

300 classes and obtained 144, or 52%, of the documents for the sample. The

syllabi were then rated for library use according to a four-point scale. They

found 43% of the syllabi examined required no library use, and only 38%

required use of the library beyond course reserves, with library use increasing

with class level (pp. 266-267).

Williams, Cody,

& Parnell (2014) started with a list of 3,125 class sections offered by the

University of North Carolina at Wilmington in the fall 2002 and spring 2003

semesters and identified 828 available via the “free web.” Of these 828, they

identified 253 upper-level courses in 34 disciplines for analysis. They found

41% of classes used the library for research papers or projects, 18% used the

library for reserve materials, 16% required library use for special projects

and book reviews, 12% offered extra-credit library assignments, and 11% offered

optional use of materials not on reserve (p. 271).

Syllabi

Analyses Involving Special Student Populations/Courses

VanScoy &

Oakleaf (2008) obtained the course lists for a random sample of 350

first-semester freshmen students from the North Carolina State University

registrar. They obtained a complete set of syllabi for 139 students from the

Internet or directly from instructors. They found 97% of the 350 students were

required to find research resources with the number jumping to 100% for the 139

students where a complete syllabi sample was available (pp. 569-570). O’Hanlon

(2007) examined winter quarter, 2006 syllabi for writing courses and senior

capstone courses at Ohio State University, analyzing 71 syllabi provided by

instructors or found on the Internet (p. 174). These 71 syllabi represented 44,

or 30%, of course sections for the writing course and 27, or 55%, of the senior

capstone courses (p. 181). Fifty-nine percent of writing course syllabi

indicated a writing assignment requiring external research (p. 182), and 70% of

the senior capstone courses mentioned the same. O’Hanlon in looking for

research related lectures in the syllabi found that while some courses offered

supplemental support, “no indication of class lectures by instructors or

librarians on research methods was found in these syllabi” (p. 183).

Syllabi

Analyses Involving Majors or Programs

Boss &

Drabinski (2013) examined a comprehensive set of 79 undergraduate and graduate

course syllabi obtained directly from the School of Business at Long Island

University. They then searched the syllabi for the word “library” and rated the

syllabi according to a set of questions developed from the Association of

American Colleges & Universities Information Literacy standards (pp.

267-268). The authors found that while 51 of the syllabi included a research

assignment, only 22 directed students to the library or a librarian (p. 270).

Dewald (2003) examined syllabi for courses required for the completion of a

B.S. in Business Administration at Penn State University. The author looked at

examples from the 2000–2001 and 2001–2002 academic years and rated library usage according to a four-point

scale (p. 35). Dewald found that 48.9% had no library use, 31.6% required

library use for short assignments, and 18.3% required significant research

assignments (p. 39).

Aims

By examining a

large group of syllabi during a specific timeframe, the librarians conducting

this study sought to identify how the library was referenced in courses at the

University. It was expected that most mentions of the library in course syllabi

would be related to spaces within the library’s physical location rather than

personnel or services. It was hoped that the following key questions could be

answered during this research study:

- Is the library

mentioned in the course syllabus?

- If the library

is mentioned, what is the context?

- Which colleges

at the university mention the library more frequently?

- Are there

opportunities for the library or librarians to provide research support or

otherwise engage with course instructors and students?

Methods

As of May 28,

2015, there were 8,433 total syllabi in the collection dating back to the 2011

pilot. For the purpose of this project, the syllabi from fall 2014 were chosen

for examination due to multiple factors. First, the set of syllabi were

cross-disciplinary and would provide data across all colleges and most subject

areas on campus. Second, the 1,258 syllabi in the fall 2014 set were relatively

higher in total number when compared to other semesters. Third, the analysis

was started in the spring 2015 semester, and fall 2014 was the most recent set

of syllabi available to analyze.

As the DSpace

software housing the collection was not managed in-house, it was not possible

to simply download the collection metadata and files. We were, however, able to

obtain a spreadsheet of the metadata for all documents uploaded to the Syllabus

Collection prior to February 2015. A script was then written in the server-side

scripting language (PHP) that visited the Handle Uniform Resource Identifier

for each DSpace record in the spreadsheet and downloaded every document in the

collection containing the string “2014.” During the download process, the

collection name was added to the start of the real document name, meaning each

document in a “2014 fall” collection could be easily identified and added to

the pool of documents to be analyzed.

After obtaining

the fall 2014 syllabi set of documents, appropriate text-mining software had to

be identified. The software had to support batch ingestion of large amounts of

PDF and Word documents, have the ability to search across the entire contents

of each document, and provide the ability to tag the discovered content with

keyword codes. Ultimately, QDA Miner was chosen for this project due to its

ability to support qualitative data analysis through coding, annotation, and

retrieval of the large syllabus collection. It is important to note two key

aspects of using this software: 1) the software is only compatible with the

Windows operating system, and 2) when importing Word documents, the text

formatting was thrown off and Unicode characters were added to some of the text

content. To counteract this, all documents were converted to PDFs.

After importing

the PDFs, metadata was applied to each document. This metadata included the

associated college, subject, and course level represented in each syllabus.

Next, the librarians brainstormed a list of keywords during multiple meetings

to use when searching across the syllabi. These keywords were related to either

the library and its services or spaces or the courses’ research assignments.

Keywords related to the library and its services or spaces were used to

identify if or how the teaching faculty referenced the library as well as what

services or spaces were promoted. Keywords related to the courses’ research

assignments were used in order to identify opportunities for subject librarians

to promote the library’s research services. Similar keywords were grouped

together to form codes. The codes include Library Spaces, Library Services, IT

Services, Librarian-Led Instruction, Independent Instruction, Resources,

People, Campus Space in the Library, Citation Management, and Research. Table 1

shows the keywords and their corresponding code category.

Table 1

Codes

Categories and Keywords

|

Code

Categories |

Keywords |

|

Library

Spaces |

Library

Classroom, Student Computing Center, Media Center, Reference, Special Collections,

SDSU Library, Love Library, Library |

|

Library

Services |

Reference

Help, Circulation/Course Reserves, Exam Space, Interlibrary Loan |

|

IT Services |

Computers,

Software, Technical Assistance, Email, Blackboard |

|

Librarian-Led

Instruction |

Library Session |

|

Independent

Instruction |

Self-Guided

Tour, Plagiarism |

|

Resources |

Databases,

Media Collection, PIN, Research Guide, eBook, Book, Article/Journal, Syllabus

Collection, Microform |

|

People |

Name,

Librarian, General |

|

Campus Space

in the Library |

Writing Center,

Financial Lab, Tutoring/Math Center |

|

Citation

Management |

APA, MLA,

Chicago Style, Bibliography |

|

Research |

Research

Paper, Literature Review, Capstone, Senior Project, Thesis, Literature

Search, Data Management |

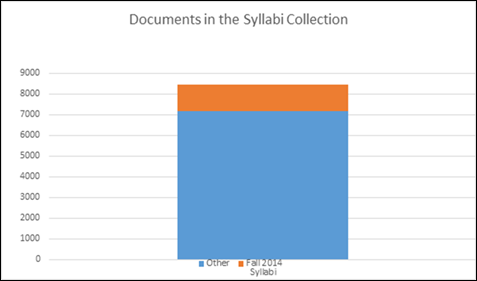

Figure 1

The Digital

Syllabus Collection hosts a total of 8,433 syllabi, with 1258 syllabi from the

fall 2014 semester—approximately 15% of the total collection.

Results & Analysis

Analysis of

Sample Set

Twelve hundred and fifty-eight syllabi from fall 2014 courses were

ingested into QDA Miner for analysis out of a total of the nearly 8,500 syllabi

in the entire collection. Thirty-two were unable to be labeled and coded due to

missing text and poor conversion by the software. The final corpus size of

1,226 syllabi represents approximately 17% of the total planned classes for

SDSU during fall 2014, as outlined by the 2014–2015 course catalog.

Seventy-one of 96 campus subjects were represented in the corpus, along

with seven colleges and the Division of Undergraduate Studies. The colleges are

represented by their short codes as follows: College of Arts and Letters (CAL),

College of Business Administration (CBA), College of Health and Human Services

(CHHS), College of Education (COE), College of Engineering (ENG), College of Professional Studies and

Fine Arts (PSFA), College of Science (SCI), and the Division of Undergraduate

Studies (OTH). Figure 2 depicts the relative prevalence of syllabi from each

college in the sample. CAL provided the most syllabi, with 520, while ENG

provided the fewest with only 26.

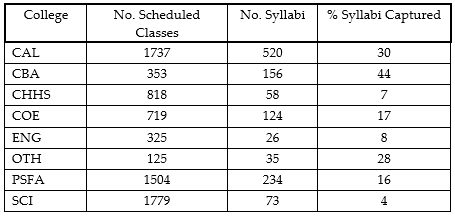

Figure 2

Relative number of syllabi from each college in the corpus and the total

number of syllabi from each college: CAL = 520, CBA = 156, CHHS = 58, COE =

124, ENG = 26, PSFA = 234, SCI = 73, OTH = 35.

Table 2

Scheduled

Classes a, Number of Syllabi Available, and Percentage of Scheduled

Classes Represented for Each College in fall 2014

aNumbers include all sections of

courses.

Relative to

the number of planned classes for the fall 2014 semester, CBA provided the

highest percentage of syllabi (44%) while SCI provided the lowest percentage

(4%). Table 2 compares the number of scheduled classes, the number of syllabi,

and the percentage represented in the corpus from each of the eight colleges.

The corpus contains syllabi from 77 unique subjects. Rhetoric and Writing

(RWS), History (HIST), and English (ENGL) were the top subject contributors of

syllabi, with 84, 77, and 62 respectively. Fifty-five percent of subjects had

fewer than 10 syllabi in the sample, with 14% of subjects having only one

syllabus each.

Codes &

Keywords Results

Of the 1,226

syllabi in the corpus, more than half did not mention any library spaces,

services, or resources, nor did they mention any papers or projects requiring

research. The following results are based on the remaining 561 syllabi. The

least frequently used keyword codes included the following: Senior Project and

Math/Tutoring Center had no mentions, and the keywords Blackboard, Syllabus

Collection, Librarian Title, Tour, Microform, Data Management, Wells Fargo,

Interlibrary Loan, and Literature Search had fewer than five mentions each. The

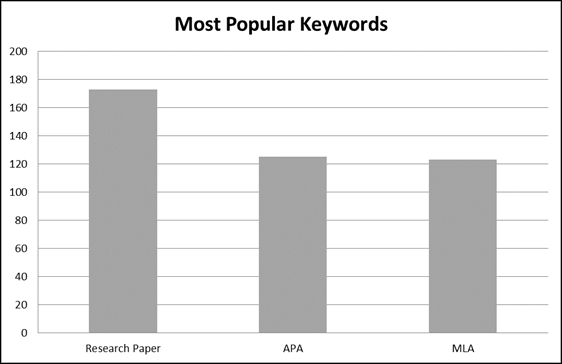

most popular keyword codes overall were Research Paper (173), APA (125), and

MLA (123), as depicted in Figure 3. After the keywords were condensed into 10

codes, the three most frequent codes in the syllabi were Citation Management

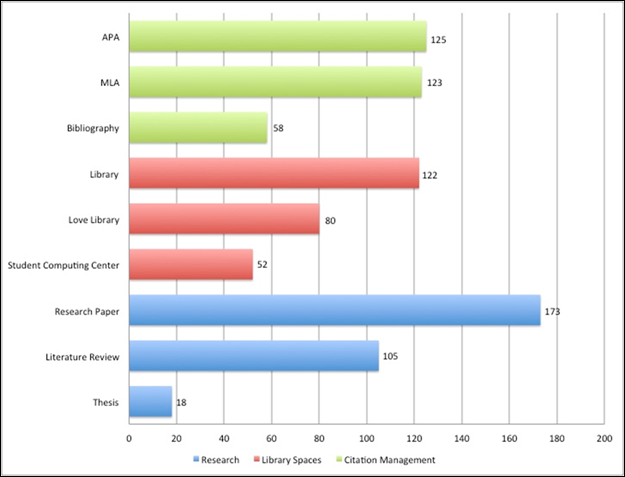

(286), Research (262), and Library Spaces (251). Figure 4 depicts the three

most frequently used keyword codes mapped to each of the top three codes.

Figure 3

Number of

occurrences in the corpus of the three most popular keywords.

Figure 4

Frequency of

individual keyword codes from the top three code categories of the corpus.

Figure 5

Frequency of

code occurrence in the corpus and likelihood of co-occurrence with other codes

in the same syllabus.

Relationships

between codes were mapped using Sorensen’s coefficient of similarity. Library

Space and Library Resources (coefficient =.500) and Library Space and Library

Services (coefficient-=.457) are most likely to appear in the same syllabus,

with Citation Management and Resource Intensive Projects (coefficient=.445)

next likely to co-occur. These two clusters are somewhat related to each other,

as they all have loose ties to Library Space, but the codes of Librarians,

Librarian-Led Instruction, and Self-Guided Instruction have almost no

co-occurrence frequency with Research, Citation Management, or Library

Services. Figure 5 shows a 2D representation of code frequency and strength of

co-occurrence with other codes. Line thickness indicates the strength of

Sorensen’s coefficient.

Syllabi from

History were the only subgroup to have mentioned keywords representing all 10

codes. General Studies, English, Management Information Systems, Child &

Family Development, and Sociology all used keywords mapping to 90% of the

codes. At the college level, CAL and CBA mapped to 100% of the codes, while ENG

was the only college to map to less than 90% of the codes. Table 3 shows the

number of code mentions from the syllabi of each college.

Table 3

Number of

Category Codesa Represented in Syllabi of Each College

aCitation Management and Library

Spaces are the two most used codes across all disciplines, followed by Library

Resources.

Figure 6

Percentage

of syllabi, out of the 1,226 syllabi sample, mentioning instruction codes

versus a resource-intensive project.

Of our

corpus of syllabi, only 38 mentioned Librarian-Led Instruction and 18 of these

syllabi were from Rhetoric and Writing, which is a core curriculum course. In contrast,

there were almost twice as many (67) syllabi mentioning Independent

Instruction, typically from requirements to complete the library’s plagiarism

tutorial or interactive tour. Eight percent of syllabi mention any type of

library instruction, while 21% mention some sort of Research. Figure 6

highlights the 18% gap between mentions of Research and Librarian-Led

Instruction sections, and the 16% gap between Independent Instruction and

Research.

Study

Limitations

While the

syllabus collection study helped to uncover broad patterns and opportunities

for library interventions, there were a number of limitations. First, the

sample chosen for this study was syllabi uploaded during the fall 2014

semester. A more accurate picture of the Library’s presence in the syllabi

would likely be revealed if the librarians analyzed the entire collection of

syllabi from the last 5 years, rather than focusing on one semester. Second,

there is not complete course coverage within each subject area of the syllabus

collection. Even though the vast majority of subjects are represented within

the collection, only certain courses within each subject area actually appear

within the collection. In order to have a better understanding of the subject

areas and possible library interventions, the library would need to reach out

to departments to ensure that there is a syllabus on file for each course

taught within a subject area. Third, a full content analysis was not performed

on the syllabi. The syllabi were searched for specific words and phrases, and

the results were contextualized by viewing the sentences surrounding the search

hits. More context for how the Library is mentioned in the syllabi could be

discovered if a full content analysis was performed.

Discussion

A collection of

syllabi can provide access to vast amounts of data about a university’s

community. Mining this data can provide libraries with much-needed information

about their communities and inspire new methods of outreach and engagement. The

information gleaned from syllabi can have an impact on a library’s collections,

service points, instructional activities, spaces, and technologies. In the case of SDSU, the

initial syllabus collection investigation has revealed multiple opportunities

for the library to intervene. Of the over 1,200 syllabi examined, only 38

included information about a librarian. Additionally, over 250 syllabi included

requirements for research or intensive resource use. There is clearly a

mismatch between the number of courses requiring research and those that

mention librarians. Librarians at SDSU can capitalize on these findings to

offer research and information literacy instruction support.

From a subject

or department standpoint, there is much to be gained. This study revealed that

many History syllabi refer to the library, yet subject support from the library

consists of several librarians serving niche areas within the department. This

finding led to recommendations that subject coverage be provided in a more

organized manner, which resulted in establishing a coordinator who works with

all librarians providing support for History. Moving forward, individual

subject librarians have planned syllabi-analysis projects based on this study

in order to uncover specific needs within the schools, departments, and colleges

they support. This will allow for a more targeted approach to engaging library

users with relevant resources and services. It will also give subject

librarians the data they need to develop and improve their services.

Conclusion

In this study, syllabi

were analyzed from the entire university, across most levels and departments.

The results revealed major differences across academic disciplines with regards

to if or how the library is mentioned in syllabi. Despite its limitations, this

study does demonstrate how academic librarians can perform a text-mining

analysis of syllabi to shed light on the information needs of their campus

communities. It also revealed gaps where the library could intervene and

provide support, especially in the area of research support. Key areas of

outreach for liaison librarians were identified, particularly in History and

writing courses. Additionally, student research expectations were further

illuminated across disciplines. It is no surprise that research is different

from one discipline to the next, but this study sheds some light on the

research expectations faculty have for the students in different disciplines.

While there are

many examples of librarians evaluating syllabi collected from the web or

directly from instructors, programs, and colleges; this study was unique in

utilizing syllabi from a central campus repository and leveraging text-mining

software. A central repository of syllabi decreases the time and effort

required for collection and access, while QDA Miner significantly reduces the

burden of hand coding text documents. We conclude that our research has

produced a replicable method for text mining digital syllabi, whether they are

in a central repository or individually collected, and for identifying areas

for improved services to faculty and students that other libraries could use to

their advantage.

References

Boss, K. & Drabinski,

E. (2014). Evidence-based instruction integration: A syllabus analysis project.

Reference Services Review, 42(2),

263-276. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/RSR-07-2013-0038

Dewald, N. (2003).

Anticipating library use by business students: The uses of a syllabus study. Research Strategies, 19, 33-45. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.resstr.2003.09.003

O’Hanlon, N. (2007).

Information literacy in the university curriculum: Challenges for outcomes

assessment. Libraries and the Academy, 7(2),

169-189. http://dx.doi.org/10.1353/pla.2007.0021

Rambler, L.K. (1982).

Syllabus study: Key to a responsive academic library. The Journal of Academic Librarianship, 8(3), 155-159. Retrieved

from https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ264858

Smith, C., Doversberger,

L., Jones, S., Parker, J., Pietraszewski, B. (2012). Using course syllabi to

uncover opportunities for curriculum-integrated instruction. Reference & User Services Quarterly, 51(3),

263-271. http://dx.doi.org/10.5860/rusq.51n3.263

VanScoy, A., & Oakleaf,

M. (2008). Evidence vs. anecdote: Using syllabi to plan curriculum-integrated

information literacy instruction. College

& Research Libraries, 69(6), 566-575. http://dx.doi.org/10.5860/crl.69.6.566

Williams, L. M., Cody, S.

A., & Parnell, J. (2004). Prospecting for new collaborations: Mining

syllabi for library service opportunities. The

Journal of Academic Librarianship, 30(4), 270-275. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2004.04.009