Research Article

What Are They Doing Anyway?: Library as Place and

Student Use of a University Library

Angelica Ferria

Curator

University Libraries

University of Rhode Island

Kingston, Rhode Island,

United States of America

Email: aferria@uri.edu

Brian T. Gallagher

Associate Professor

University Libraries

University of Rhode Island

Kingston, Rhode Island,

United States of America

Email: bgallagher@uri.edu

Amanda Izenstark

Associate Professor

University Libraries

University of Rhode Island

Kingston, Rhode Island,

United States of America

Email: Amanda@uri.edu

Peter Larsen

Associate Professor

University Libraries

University of Rhode Island

Kingston, Rhode Island,

United States of America

Email: plarsen@uri.edu

Kelly LeMeur

Learning Commons Librarian

University Library

Roger Williams University

Bristol, Rhode Island,

United States of America

Email: klemeur@rwu.edu

Cheryl A. McCarthy

Professor Emerita

Graduate School of Library

and Information Studies

University of Rhode Island

Kingston, Rhode Island,

United States of America

Email: chermc@uri.edu

Professor

University Libraries

University of Rhode Island

Kingston, Rhode Island,

United States of America

Email: dmongeau@uri.edu

Received: 8 Nov. 2016 Accepted:

10 Feb. 2017

![]() 2017 Ferria, Gallagher, Izenstark, Larsen, LeMeur,

McCarthy, and Mongeau. This is an Open Access article distributed under

the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

2017 Ferria, Gallagher, Izenstark, Larsen, LeMeur,

McCarthy, and Mongeau. This is an Open Access article distributed under

the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

Abstract

Objective - To

determine student use of library spaces, the authors recorded student location

and behaviors within the Library, to inform future space design.

Methods - The case study method was used with both quantitative and

qualitative measures. The authors had two objectives to guide this assessment

of library spaces: 1) To determine what

library spaces are being used by students and whether students are working

individually, communally, or collaboratively and 2) To determine whether

students use these spaces for learning activities and/or social engagement.

Results - After

data collection and analysis, the authors determined students are using

individual or communal spaces almost equally as compared with collaborative

group spaces. Data also revealed peak area usage and times.

Conclusion - Observed

student individual and social work habits indicate further need for spaces with

ample electrical outlets and moveable tables. Further study is recommended to

see whether additional seating and renovated spaces continue to enhance

informal learning communities at URI and whether the Library is becoming a

“third place” on campus.

Introduction

In 2008, Bennett

defined information commons as spaces

in libraries with technology that support individual learning and learning commons as spaces in libraries

that impact or enhance the learning experience by enacting the institutional

mission through collaborative partnerships with “academic units that establish

learning goals for the institution” (Bennett, 2008, p. 183). In 2011, the University of Rhode Island (URI)

redefined its library, rebranding the University Library with the name Robert

L. Carothers Library and Learning Commons (the Library). The

University of Rhode Island is a public Land, Sea, and Urban Grant institution,

offering Bachelors, Masters, and Doctoral Degrees, with three campuses across

the state. The Library is located on the main campus in Kingston, RI. Of URI’s

nearly 17,000 undergraduate and graduate students, approximately 6,700 live on

campus (URI Communications and Marketing, undated).

While the Library’s

mission to acquire, organize, preserve, and provide access to resources in all

formats and provide instruction in their use has remained constant, its role on

the Kingston, RI, campus requires new and evolving ways of thinking about its

physical spaces. The Library’s spaces have evolved into places of individual

intellectual inquiry as well as collaborative engagement where students connect

with others to build shared learning communities.

Academic library

planners have begun to embrace the notion of creating welcoming shared learning community spaces

where users connect informally and the library can become the third place on campus. Ray

Oldenburg, in his book The Great Good

Place (1991), defined the third place

in a community as a place that provides the diversity of human contact where

people come together to connect and build a shared community when not at home

(first place) or work (second place). Arguably, academic libraries can become

that third place on campus, with spaces that welcome a diversity of human

contact that nurtures growth when outside the classroom (first place) or campus

housing (second place). The Library as the third place can enrich campus life,

create a sense of belongingness, and support the institutional mission of

lifelong-learning. Thus, the Library spaces at URI, were assessed for their

impact on how students are using library spaces by identifying what spaces are

used and whether students work individually, communally, or collaboratively.

Literature Review

The evaluation of the

academic library as place, and specifically its impact on learning, has

challenged the library profession, administrators in higher education, and

accreditation agencies. Joan Lippincott of the Coalition of Networked

Information (CNI) stated in an interview: “I’d like to challenge the notion

that brand-new, beautiful learning spaces in and of themselves can change

learning. I believe that it has to be a combination of the space and the

pedagogy and the technology” (Lippincott, van den Blink, Lewis,

Stuart & Oswald, 2009, p. 10). Lippincott (2006) advocated making

managerial decisions in libraries based on assessment data that measures the

effectiveness, efficiency and extensiveness of learning spaces in libraries.

There is growing concern for universities to evaluate their library facilities,

services, technology, and information resources to determine the impact on

student learning and how libraries support the research and public service

mission of the institution.

According to Fox and Doshi (2013),

group spaces are growing. Additionally, Diller (2015) identified that study

areas are the second highest used library spaces. Khoo, Rozaklis, Hall, and

Kusunoki (2016) commented on redesigned library spaces to encourage group

interaction where talking, moving around, and moving furniture is acceptable.

The advent of digital tools and

resources as well as pedagogical shifts that emphasize collaboration, creation,

and student centered learning have changed the library landscape.

Libraries have responded to calls for

user-centered learning with good reason; student-centered learning is

social—active and interactive (Foster & Gibbons, 2007). In that tradition,

Montgomery (2014) explained: “The importance of library space is shifting from

the content on our shelves to how students use and learn in our space” (p. 71).

Trying to remain relevant, libraries allocate and reallocate space in

recognition of the pedagogical shift toward interaction among learners (Jackson

& Shenton, 2010) by becoming physical and virtual platforms for knowledge

creation.

At the same time, there are those who

want the academic library to honor its historical mandate as a place for quiet

study and contemplation. Gayton (2008), in particular, supports this role for

the library by pointing out that, in spite of its diminished importance as a

storehouse and access point, gate counts have remained steady. Similarly, Demas

(2005) emphasized the library’s cultural roles. Gayton and Demas urge decision

makers not to throw out the baby with the bathwater. Gayton (2008) clarifies,

There is a profound

difference between a space in which library users are engaged in social

activity and a space in which they are engaged in communal activity. Social

activity in a library involves conversation and discussion among people, about

either the work at hand or more trivial matters. Communal activity in a library

involves seeing and being seen quietly engaged in study (p. 61).

There is value to learning that takes

place independently or communally in a shared space; it is a privilege students

do not want to risk losing.

Yoo-Lee, Tae, and Velez (2013) found

that students responded to two survey questions with contradictory preferences

for library spaces: “37 percent of the participants chose quiet study spaces

and 28 percent, social spaces. However, 35 percent of them responded that they

used both quiet spaces and social spaces almost equally” (p. 503).

Looking at the quantitative results of

space studies introduces notions of capacity and occupancy that warrant

consideration. Applegate (2009) noted, “Previous observations had shown that

unaffiliated people (people not arriving together or working in a group) almost

never preferred to sit right next to each other, so an area might reach ‘full’

comfortable use at 50% of maximum capacity” (p. 343). In their discussion about

a place and space survey Khoo et al. (2016) elaborated on this point: “Thus,

while seating availability is initially evidenced by an empty table, this

availability is reduced incrementally and ambiguously, . . . In agreement with Gibbons and Foster,

this study suggests that tables may be perceived to be ‘full’ when only

approximately 50 percent of the seats at each table are occupied” (p. 7).

Khoo et al. (2016) advocated the use of

mixed methods when studying library spaces. Montgomery (2014) and Holder and

Lange (2014) both used mixed-methods successfully. As Holder and Lange argued,

“Using survey and observation methods together provided a more complete picture

of user satisfaction with the spaces, as well as user preference for particular

areas and furniture types” (p. 8).

Hall and Kapa (2015) found in their

study at Concordia University that some students prefer to work in isolation,

as illustrated by one of their survey responses: “More single study spaces. Not

beside desks or other people” (p. 14). This is consistent with Applegate’s

(2009) study where 30-40% of group study room users were individuals, despite

signage encouraging group use. As

planning for spaces goes forward, it is worth considering the value of offering

rooms for individuals versus space intended for groups, or using “territorial

dividers” to subdivide groups as recommended by İmamoğlu and Gürel (2016, p.

65).

Aims

Embracing the concept

of the third place along with Bennett’s 2008 definition of the library as

learning commons, the Library administration at URI assembled a team of

librarians and staff during the 2014-2015 academic year to examine the

evolution of library spaces to assess how the new spaces are being used and

whether the Library is becoming the third place on campus. The assessment team

hoped to identify student preferences for type of seating and level of

engagement through the behavior and activities observed. Students were not

asked their preferences, however we could identify the most heavily used spaces

and times as well as how students were using them for individual, communal, or

group activities on each level (i.e., lower level, first floor, second floor,

or third floor).

The librarians used

the following research questions as guides:

1. What library spaces are being used by students and are

students working individually, communally, or collaboratively?

2. How do students use these spaces for learning activities

and/or social engagement?

Methods

The case study

methodology used both qualitative and quantitative measurements to assess the

overarching research questions. The assessment team recorded sweep counts and

unobtrusive observations on maps and coding sheets and examined aggregated

usage statistics including gate counts to get a complete picture of library

use.

The assessment team

performed sweep counts of students using the Library spaces for one week at the

end of two semesters, Fall semester (December 1-7, 2014) and Spring Semester

(April 25-May 1, 2015), three times a day (10 a.m.-12 p.m., 2-4 p.m., and 8-10

p.m.). The sweep counts identified the number of students using the Library as

well as the activities of those students for each day and time. Activity codes

included reading, writing, using devices, studying in groups, and using movable

white boards. The assessment team also observed behavior: individual, communal,

or group study. Team members submitted the coded information sheets and key

personnel created Excel spreadsheets to compile the numbers and highlight

comparisons of times, days, and semesters to determine peak use times. No identifying

information about participants was recorded and thus, user privacy was

protected.

In assessing the use of space, the URI

assessment team devised a strategy consistent with McCarthy and Nitecki (2011),

Given and Leckie (2004), and Applegate (2009). The URI researchers identified

the use of library space with sweep counts and structured observations of

activities and behaviors. The URI researchers recorded information directly on

maps and coding sheets with predetermined categories similar to coders in other

studies (May, 2011; McCarthy & Nitecki, 2011).

Quantitative

Assessment Measures

1. What Library spaces are being used

by students and are they working individually, communally, or collaboratively?

The team identified

space use by counting and recording the number of people occupying seats in the

various areas (e.g., tables, group study rooms, informal spaces such as soft

seating, and the 24 Hour Room) on all four levels of the Library for each day

and time slot during the two sweep count weeks. Library personnel created Excel

spreadsheets from the coded data sheets to show occupancy rates, and the

assessment team analyzed the combined data to determine the most heavily used

seating areas, peak times of use, and how spaces were being used.

Qualitative

Assessment Measures

2. How

do students use these spaces for learning activities and/or social engagement?

The assessment team

observed and recorded activities on coding sheets for each time period and date

to identify students’ activities and behaviors, to record how the spaces

appeared to enhance informal learning communities. These coding sheets were

compiled into spreadsheets to compare observations of activities and behaviors such

as reading, writing, and using devices and to identify commonalities using

content analysis.

Observers determined whether students were engaged individually, communally

(working alongside), or collaboratively (working together in groups) as well as

their activities and behaviors. The assessment team analyzed these findings

individually and collectively for relations between the two semesters, times of

day, days of the week, levels of the building, and so on to determine the

effectiveness of the Library’s environment in building a shared learning

community.

Table 1

The Library

Floor Level Identification

|

Floor Location |

Atmosphere/Behavior |

Noise Level |

Furnishings |

|

Lower Level |

Mostly individual study, some flexible

use |

Quiet, Soft voices |

Carrels, some small tables |

|

First Floor/ Main Floor |

Meet and greet, constant motion, café in

the 24 Hour Study Room, Learning Commons spaces, group study rooms,

presentation room, and collaborative spaces with whiteboards and flat screens

for projection, as well as moveable furniture and roving white boards |

Conversation, Collaboration, Mall or

busy lobby |

Grouped soft seating, high top bar

seating, café tables, booths, moveable tables and chairs with wheels, |

|

Second Floor |

Group work or communal study at tables

alongside others, flexible use with roving whiteboards, group study rooms and

graduate carrels (small rooms) |

Conversation, Café style seating |

Moveable tables and chairs on wheels,

bar seating, some carrels and some soft seating, group study rooms |

|

Third Floor |

Library designated quiet zone |

Silent |

Carrels and tables |

Results and Discussion

Student Use of Spaces

by Floor

Tracking student occupancy by floor is

only one aspect of measuring use of space. Another method is to measure use of

space by specific location, time of day, and number of seats available. In this

study, discerning students’ choices of seating may be influenced by segregation

of library atmosphere and noise level by physical floor level as well as by

flexible furnishings. The exception is the third floor, which the Library has designated

as a quiet zone. Enforcement is primarily self-policing by other users. Table 1

offers a brief snapshot of each floor, its atmosphere, and behaviors

identified.

As the total number of seats varies

greatly by floor, preferred use was measured by number of seats filled as

compared to number of seats available on each floor. Counts provided a clear

picture of preferred seating across various floors by both day of week and time

of day. Although the percentage of seats actually taken may be one-third or

one-half full, the actual number of tables occupied appears to be a full house.

There may only be one or two students at a table with four to six seats.

Students arriving unaccompanied seemed reluctant to approach an

already-occupied but not fully-used table, unless they knew the occupants.

This is consistent with what Applegate (2009) and Khoo et al. (2016) observed

in their studies.

The relatively high occupancy of first

floor seating can be explained by the newly renovated Learning Commons area

with the highly popular booths (with 1-4 students), flexible and moveable

tables and seats, curtained areas, café-style tables, laptop-bar high seating,

and a 24 Hour Room with a café where students frequently meet and greet and

wait for their next class, or utilize their own electronic devices as well as

library materials and white boards. Thus, the first floor areas including the

Learning Commons and the 24 Hour Room, appear fully occupied throughout the day

and evening. Table by table, however,

occupancy was approximately 30% of the seats occupied with an increase in seat

occupancy between 2-4 p.m.

Table 2

Behavioral Use of Library Spaces, by

Floor

|

|

Date |

IS/Communal |

GS/Social |

|

Lower Level |

December 2014 |

60.9% |

39.1% |

|

April 2015 |

54% |

46% |

|

|

First Floor |

December 2014 |

48.2% |

51.8% |

|

April 2015 |

51.2% |

48.8% |

|

|

Second Floor |

December 2014 |

40.1% |

59.9% |

|

April 2015 |

41.6% |

58.4% |

|

|

Third Floor |

December 2014 |

69.8% |

30.2% |

|

April 2015 |

71.1% |

28.9% |

|

|

Average for all floors |

December 2014 |

52% |

48% |

|

April 2015 |

47.8% |

52.2% |

The lower level and third floors had

the least amount of students occupying seats and they also do not have as much

seating nor have moveable tables or seats. Both levels are used primarily for

quiet study or individual work in carrels and thus, may explain the significant

difference in variation of seating by floor. Observers noted that, where

carrels were placed side-by-side, students showed a reluctance to take a seat

next to an occupied carrel.

The first floor sometimes had double or

triple the occupancy of the next highest used floors, with a peak usage from

2-4 p.m. on Monday through Friday. The second and third floors were the next

highest in use. Occupancy of these floors typically varied by less than twenty

users (second floor being slightly higher) with patterns of occupancy that

tended to move in tandem. Like the first floor, peak time was 2-4 p.m. daily

Monday through

Friday. The lower level was by far the least used floor, with only half the use

of the second and third floors. Unlike the rest of the building, use of the

lower level remained moderately steady, with variations seldom rising or

falling more than 15 students between scheduled counts. Saturday occupancy grew

steadily across all floors for time periods measured while Sunday’s use spiked

at 4-6 p.m. in May but in December the numbers grew steadily throughout the

day.

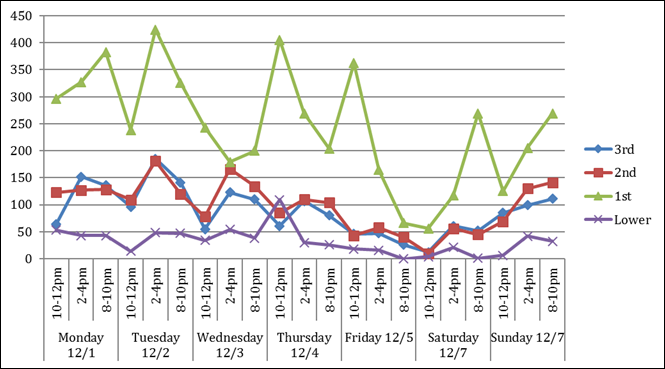

Figure 1

Carothers Library occupancy by floor,

day, and time for Fall 2014.

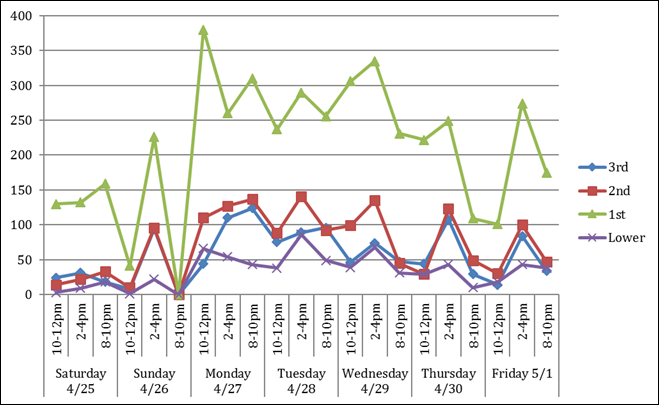

Figure 2

Carothers Library occupancy by floor, day, and time

for Spring 2015.

In summary, first through third floor

use was consistent comparing both semesters, with heaviest use from 2-4 p.m.

Monday-Friday. Lower level floor use was steady throughout all the observation periods

although the number were the least. Saturday use was steady across all floors

with a small spike from 4-6 p.m. Sunday use in December showed a steady

increase during the day and night, but in May, use spiked from 2-4 p.m. The

December count (possessing greater variations) clearly aligns with the fact

that classes were still in session, while the April count had less drastic

variations with May 1 as a reading day prior to the start of exams.

While

analyzing occupancy numbers by day of the week tends to support the

observations drawn from Table 2 (e.g., usage tends to be highest in the 2-4

p.m. time slot, the first floor is used noticeably more than the other floors),

the data does not reveal further meaningful patterns. More than two weeks of

observation are needed to uncover significant patterns at the week by week

scale. Note that the low values for Sunday, April 26, 8-10 p.m., are the result

of lack of data rather than absence of students.

Behavioral Use

of Spaces

The framework devised to show how

students use library spaces originally identified three criteria to be observed

as a set of behaviors defined as

Independent Study (IS), Alongside Study (AS), and Group Study (GS). The charts

created to record data for the sweep counts also used the codes IS, AS, and GS

to record behaviors observed. Discussion by the assessment team after the first

count identified that observers may interpret these categories differently, and

to label all behavior as study may be

inaccurate. Thus, the original category of studying alongside (AS) was merged

into the existing heading of individual study (IS) because group work (GS)

should indicate active collaboration with interaction at the time of

observation. These categories correlate to a similar examination of students

using library space by Holder and Lange (2014) who also found it necessary to

clarify proximity: “interaction (students working alone/students working

collaboratively/other)” (p. 9).

Some observers noted that it was a

subjective call whether to label student use IS or AS when they were working

independently but at the same table or space although they were not directly

interacting. So alongside (AS) became identified as communal and was combined with IS for the count. Group work implied

interaction among participants and may incorporate social activities as well.

Space Use

Table 2 provides an

overview of how students were using each floor during each of the study

periods. The

lower level has more carrels and fewer tables than other floors and provides

more individual/communal activity rather than group work/study. Accordingly, the results showed

significantly more individual work: the lower level had 20% more individual

than communal study in December and approximately 10% more in April.

The first floor, which includes a

Learning Commons with booths, cluster soft seating, high top and moveable

tables, a café in the 24 Hour Room with moveable seating, as well as service

points (circulation and reference), shows almost equal use of space between

individual/communal (IS/Communal) versus group/social activities (GS/Social).

Data for this floor closely parallels findings for the Library as a whole and

is fairly consistent between semesters with almost equal behavioral use with

48% individual/communal versus 52% group work in December with 51% individual

versus 49% group work in April.

The second floor shows significantly

more Group/Social activity compared with all floors and is consistent over two

semesters with approximately 40% individual versus 60% social. One reason for

the high usage is the preference shown by many Greek Society students who use

these spaces for communal study.

The third floor, designated as the

silent floor, has vastly more individual/communal than group/social use and is

consistent between semesters with the highest number of individual use of all

floors with approximately 70% individual and only 30% group or social activity.

When all floors are averaged for

behavioral use of space, it is almost equally distributed between IS/Communal

and GS/Social. In the observation of behavior, the counts indicated that the

lower level 60% vs. 40% preference for individual versus group activity and

third floor (quiet area) approximately 70% vs. 30% preference for individual

over group activity; whereas, the first floor showed nearly equal preference

for individual vs. group activity but only the second floor was higher in group

work/activity with approximately 40%-60% individual vs. group engagement. The

average totals for all floors for both semesters indicate approximately 52% and

48% individual vs. group activity for December but the opposite, 48% - 52%

individual vs. group activity, for April.

The data collected about behavioral use

of library spaces revealed the total average percent for all floors in the

Library is almost equal for individual/communal work vs. group work or social

activity/learning. The results indicate that students at URI gather in the library

to work both communally and collaboratively in almost equal amounts throughout

the day and evening with peak times in the late afternoon. Thus, it appears

that more tables and seats are needed to accommodate students’ desire to work

communally or collaboratively.

The data is notably consistent.

Observation at the Library demonstrates that close to 50% of the library is

used for independent study or communal alongside and approximately 50% of the

library space is used for group collaborating or social engagement. Some

observed activities by groups include collaborative learning projects using

white boards with equations, scientific data, charts, diagrams, engineering

formulas, preparing presentations, and practicing performances, as well as

using roving white boards or shared electronic devices and flat screens in the group

study rooms. This sort of collaborative work supports the learning commons

concept as advocated by Bennett (2003). At the same time, regardless of

intention or design, library space is being used communally, individually, for

group work with socializing, as well as for interacting with both print and

electronic information resources.

Group study rooms are very popular

spaces. The Library has 21 group study rooms of various configurations on 3 of

the 4 levels. Fifteen of these rooms can accommodate up to six students, and

six rooms are intended for one or two students. Students frequently indicate

preferred spaces when they request a study room, however, they were identified

as full even if only one or two students occupied the room.

Some group study rooms have a small

counter permanently mounted at desk height with seating for one or two

students. Others have freestanding tables with wall-mounted whiteboards, and

some have large monitors in the rooms in the Learning Commons where students

can plug in their laptops for greater screen visibility during group work.

Rooms on the second and third floor of the Library are sometimes less appealing

than rooms on the first floor due to their older furnishings, but they remain

quite popular and all are frequently full on all floors. Group study rooms are

available on a first-come-first-served basis only, with no option to reserve

rooms. Students can check out a key to a room for up to three hours at a time,

and can renew the room if no other students or groups are waiting to use the

next available room.

While the group study rooms were often

in use by groups during both survey periods, on a number of occasions only one

student occupied a small group study room. In most cases, however, when large

group study rooms were in use, groups of more than two students were using

them. The few exceptions to this trend—for example, only one student occupied a

room intended for use by three or more students—occurred during the early hours

on weekends. This is a time when Library use as a whole is lower than average,

and there is consequently lower demand for group study spaces.

Occupancy Rate by

Floor and Hour

Although the building rarely has more

than 20-35% total seat occupancy during the observation weeks, it was noted

that frequently only 1-2 students occupied tables that seat 4-6, further

confirmation of Applegate’s observations (2009). Students seem

reluctant to sit next to unfamiliar students which likely accounts for similar

low occupancy of the carrels on the lower level and third floor, as noted

above. The 2-4 p.m. time period Monday-Friday accounts for the highest

occupancy rates with the 8-10 p.m. time slot generally close behind. The

evening count was almost always higher than the morning count in December but

the opposite was true in the Spring semester. Another curiosity is that the

first floor use drops off more than other floors between the afternoon and

evening especially during the Spring semester count. There is no accurate way

to determine why usage declines between late afternoon and evening without more

intrusive interactions with the students. It is obvious from the data summary

charts that the lower level and third floor (designated quiet zone) are

underutilized (see Table 3).

Table 3

Occupancy Rate (Occupied Seats vs.

Available Seats) by Floor and Hour

|

|

December 2014 |

April 2015 |

|

Lower Level |

|

|

|

Totals |

525/2289 (22.9%) |

557/2289 (24.3%) |

|

10-noon |

153/763 (20.0%) |

165/763 (21.6%) |

|

2-4pm |

182/763 (23.9%) |

266/763 (34.9%) |

|

8-10pm |

190/763 (24.9%) |

126/763 (16.5%) |

|

First Floor |

|

|

|

Totals |

2720/14700 (18.5%) |

3548/14700 (24%) |

|

10-noon |

727/4900 (13.9%) |

1255/4900 (25.6%) |

|

2-4pm |

1130/4900 (19%) |

1490/4900 (30.4%) |

|

8-10pm |

893/4900 (16.8%) |

783/4900 (16%) |

|

Second Floor |

|

|

|

Totals |

1575/5796 (27.2%) |

1283/5796 (22.1%) |

|

10-noon |

427/1932 (24.9%) |

365/1932 (18.9%) |

|

2-4pm |

605/1932 (31.3%) |

661/1932 (34.2%) |

|

8-10pm |

543/1932 (28.1%) |

257/1932 (13%) |

|

Third Floor |

|

|

|

Totals |

1504/7833 (19.2%) |

1005/7833 (12.8%) |

|

10-noon |

326/2611 (12.5%) |

240/2611 (9.2%) |

|

2-4pm |

599 /2611 (22.9%) |

541/2611 (20.7%) |

|

8-10pm |

579/2611 (22.2%) |

224/2611 (8.6%) |

Limitations

Discussion of initial data exposed a

discrepancy: unobtrusive observation could not definitively state whether

people sitting in close proximity to one another were working collaboratively

or if those students were working communally by sharing space. Consequently,

the team adjusted data categories to reflect the reality of what could be

observed. This reclassification of terms reflects a standard downside to

research that is limited to observation as also observed by May (2011). Without

direct intervention by either interviewing or surveying students, researchers

could not define some behaviors and activities precisely, such as using a

computer for study versus social media. Likewise, the findings could have been

enhanced by surveys similar to those from Yoo-Lee et al.’s (2013) investigation

of how students perceive space. Because we did not ask students directly what

spaces and modes of study they preferred, we cannot speculate on their

preferences with any great certainty. Since this study used multiple

observers, the assessment team pre-tested the coding sheets and clarified codes

to minimize discrepancies and inconsistencies, however subjectivity among

coders must be acknowledged.

Conclusions and Further Research Questions

This study broadly

supports the conclusions of other researchers. For example, Montgomery (2014)

found that “…the renovation provided users with a better space to work alone in

addition to it being used for social learning. We did not anticipate users

seeking individual studying space in a social learning environment, but

welcomed the flexibility of the space to meet this learning behavior” (p. 73).

Additionally, Holder and Lange (2014) suggested that students’ use of space is

need specific: as a consequence of either opportunity or necessity students

repurpose space to meet their individual, time sensitive needs. Their data

demonstrated that an area intended for collaborative study on the third floor

of McGill University’s McLennan Building was used for quiet, singular study 50%

of the time (Holder & Lange, 2014). The shared use of space observed at URI

also supports theories and findings for the need of both types of spaces as

posited by Freeman (2005), Demas (2005), and Lin, Chen, and Chang (2010).

The URI case study

reveals that the Library is a popular venue for student use with almost equal

individual or communal study as compared to group work or social engagement

during these two weeks of observation. The Library provides both a refuge for

quiet study as well as a venue for social activity or collaborative engagement,

thereby creating social learning communities where students want and need both

types of spaces. Differences are minimal between communal/social use as

compared to individual/quiet use of spaces on each floor when the total

building use is considered. It also speaks to how students use any space available, although the renovated first floor, including the

Learning Commons area, 24 Hour Room and café, are the most aesthetically

appealing spaces and the most used spaces in the Library. Given these

observations, it is reasonable to say, at least provisionally, that the

Carothers Library is serving as the third place on the URI Kingston campus.

Without surveying or interviewing users, however, researchers cannot know why

students have chosen to use a particular library space.

Determining the need

for both kinds of places (quiet individual study versus collaborative

engagement) in the wider campus environment would help determine whether the

Library has become the sole third place on campus or whether there are other

spaces serving these needs. Further research on campus-wide availability of places for

communal and social spaces could inform an understanding of what students

desire and prefer and give a better view of the Library’s central role in

providing those needs. That kind of study might include interviews or survey

questions about the appropriate applicability of other

spaces to connect and build shared learning communities, such as in dormitories, social

houses, classroom buildings, the student union, or other available

spaces on campus for study or social and communal use by students.

If those responsible for designing

library spaces document how students actually use spaces with an understanding

of student-centered learning, then it may be possible to coordinate the

intended function and actual use of the Library’s communal space for both

intellectual conversations and social engagement.

Answers to the questions of purpose and

student preferences by incorporating a survey or interviewing students could

supplement the library observations and sweep counts and thus provide more

valuable data for the allocation of both space and money. The activity recorded

during this study speaks to student use of spaces and types of behavior

observed but not students’ specific preferences.

As

academic libraries evolve, library spaces should be continuously assessed,

identified, and renovated to further identify how they are meeting the

teaching, learning, research, and social learning needs of the university

community. This first assessment study of the Library as place at URI helped to

identify what spaces are being used and how students are using them. Since this

study, the Library has already added significant student seating and additional

service points. Future iterations of this study should address these physical

changes, as well as develop tools to explore student choices and opinions

rather than relying solely on observation.

Questions for Further

Research on Use of Library Spaces

To determine whether the academic library

is becoming the third place on campus, a comprehensive campus snapshot should

investigate the availability and quality of spaces for use across campus and

incorporate student preferences. Questions for future investigations of the

impact of the Library spaces on the learning community may include:

1.

Is

the Library becoming the sole third

place on campus where students go to

connect and to study individually, communally, or collaboratively by building informal

learning communities outside the classroom?

2.

How

do library spaces and services support the institutional mission for student

success and what spaces are needed for future learning and engagement?

Acknowledgements

The authors also wish to acknowledge

the contributions by the following colleagues: Lauren Mandel for use of her

data and mapping library space use, Mary C. MacDonald and Mona Niedbala for the

use of their data, and Celeste DiCesare for her work designing maps and coding

sheets.

References

Applegate,

R. (2009). The library is for studying: Student preferences for study space. The Journal of Academic Librarianship, 35(4),

341-346. doi:10.1016/j.acalib.2009.04.004

Bennett,

S. (2003). Libraries designed for

learning. Retrieved from Council on Library and Information Resources

website: http://www.clir.org/pubs/reports/pub122/pub122web.pdf

Bennett,

S. (2008). The information or the learning commons: Which will we have? The Journal of Academic Librarianship, 34(3),

183-185. doi:10.1016/j.acalib.2008.03.001

Demas,

S. (2005). From the ashes of Alexandria: What’s happening in the college

library? In Library as place: Rethinking

roles, rethinking space (pp. 25-40). Retrieved from Council on Library and

Information Resources website: https://www.clir.org/pubs/reports/pub129/pub129.pdf

Diller,

K. R. (2015, March). Reflective practices:

Library study spaces in support of learning. Paper presented at the

Association of College & Research Libraries conference, Portland, OR. Retrieved from http://www.ala.org/acrl/sites/ala.org.acrl/files/content/conferences/confsandpreconfs/2015/Diller.pdf

Foster,

N. F., & Gibbons, S. L. (2007). Studying

students: The undergraduate research project at the University of Rochester.

Chicago, IL: Association of College and Research Libraries.

Fox,

R., & Doshi, A. (2013). Longitudinal assessment of “user-driven” library

commons spaces. Evidence Based Library

and Information Practice, 8(2), 85-95. doi:10.18438/B8761C

Freeman,

G. T. (2005). The library as place: Changes in learning patterns, collections,

technology, and use. In Library as place:

Rethinking roles, rethinking space (pp. 1-9). Retrieved from Council on

Library and Information Resources website: https://www.clir.org/pubs/reports/pub129/pub129.pdf

Gayton,

J. T. (2008). Academic libraries: “Social” or “communal”? The nature and future

of academic libraries. The Journal of

Academic Librarianship, 34(1), 60-66. doi:10.1016/j.acalib.2007.11.011

Given,

L. M., & Leckie, G. J. (2004). “Sweeping” the library: Mapping the social

activity space of the public library.

Library & Information Science Research, 25(4), 365-385.

doi:10.1016/S0740-8188(03)00049-5

Hall,

K., & Kapa, D. (2015). Silent and independent: Student use of academic

library study space. Partnership: The

Canadian Journal of Library and Information Practice and Research, 10(1),

1-38. doi:10.21083/partnership.v10i1.3338

Holder,

S., & Lange, J. (2014). Looking and listening: A mixed-methods study of

space use and user satisfaction. Evidence

Based Library and Information Practice, 9(3), 4-27. doi:10.18438/B8303T

İmamoğlu,

Ç, & Gürel, M. Ö. (2016). “Good fences make good neighbors”: Territorial

dividers increase user satisfaction and efficiency in library study spaces. The Journal of Academic Librarianship, 42(1),

65-73. doi:10.1016/j.acalib.2015.10.009

Jackson,

M., & Shenton, A. K. (2010). Independent learning areas and student

learning. Journal of Librarianship and

Information Science, 42(4), 215-223. doi:10.1177/0961000610380821

Khoo,

M. J., Rozaklis, L., Hall, C., & Kusunoki, D. (2016). “A really nice spot”:

Evaluating place, space, and technology in academic libraries. College & Research Libraries, 77(1),

51-70. doi:10.5860/crl.77.1.51

Lin, P., Chen, K., & Chang, S. (2010). Before there was a

place called library – Library space as an invisible factor affecting students'

learning. Libri, 60(4), 339.

doi:10.1515/libr.2010.029

Lippincott,

J. K. (2006). Linking the information commons to learning. In D. Oblinger

(Ed.), Learning spaces (pp. 7-18).

Washington, D.C.: Educause.

Lippincott,

J. K., van den Blink, C. C., Lewis, M., Stuart, C., & Oswald, L. B. (2009).

A long-term view for learning spaces.

EDUCAUSE Review, 44(2), 10-11. Retrieved from http://er.educause.edu/

May,

F. (2011). Methods for studying the use of public spaces in libraries. Canadian Journal of Information and Library

Science, 35(4), 354-366. doi:10.1353/ils.2011.0027

McCarthy,

C. A., & Nitecki, D. A. (2010, October). An assessment of the Bass Library

as a learning commons environment. Presented at the Library Assessment

Conference, Baltimore, MD.