Evidence in Practice

Transparency and Tiers: Restructuring a

Publisher Deal with a Modified Decision Matrix

Denise Pan

Associate Dean, Collections and Content

University Libraries

University of Washington

Seattle, Washington, United States of America

Email: dpan@uw.edu

Gabrielle Wiersma

Head, Collection Development

University Libraries

University of Colorado Boulder

Boulder, Colorado, United States of America

Email: gabrielle.wiersma@colorado.edu

Received: 16 June 2016 Accepted:

19 July 2016

![]() 2017 Pan

and Wiersma. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the

Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

2017 Pan

and Wiersma. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the

Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

Setting

The

University of Colorado (CU) System consists of five separately administered

libraries, located at four campuses and at three institutions (Boulder, Denver,

and Colorado Springs). Each campus has grown substantially over time, and the

budgets for library materials have not kept pace with increased demand for

resources or the cost of serials inflation. The CU libraries are members of

several consortial groups that negotiate competitive pricing and facilitate

cooperative purchasing. CU Deans and Directors convened the CU Libraries

Electronic

Resources

Team (CLERT), a representative group of librarians with acquisitions and

collection development responsibilities, and charged them to negotiate

consistent access, at the best possible system-wide pricing, for common needs.

In addition to CLERT, most of the CU libraries also participate in the Colorado

Alliance of Research Libraries (Alliance), a regional consortium of thirteen

academic and research libraries. Like many consortia, participating member

institutions benefit from sharing resources through cooperative purchasing and

lending. The Alliance has successfully negotiated several license agreements

for member libraries including major databases and journal packages.

Problem

The

costs to participate in most consortial deals are typically based on publisher

pricing and are generally lower than list price or the cost for a single

library to participate on its own. One particular big deal journal package was

called into question when eleven Alliance member libraries participated in the

purchase; however, the four CU libraries paid for nearly half of the costs. The

CU libraries questioned why they were paying such a large proportion and

whether CLERT could negotiate a better deal for the CU System.

The

historical cost distribution for this particular package was based on print

journal expenditures. Overtime the burden of publisher increases were

experienced disproportionately for the CU system who subscribed to nearly half

of the titles in print when the package was converted to an online package. Most Alliance libraries shared a longstanding

belief that CU Boulder possessed the greatest capacity for absorbing high

inflation costs for serials because it had one of the largest materials

budgets. Initially, this understanding possessed some truth, and CU Boulder

traditionally subsidized the costs of shared resources by paying a larger

amount.

However, CU Boulder

experienced three rounds of budget cuts resulting in serials cancellations

after the initial deal was negotiated and absorbing inflation became

increasingly difficult. Other Alliance libraries

felt similar economic pressures and could not absorb increased subscription

costs either. The deal was in jeopardy of breaking apart. An Alliance task

force was convened to find out what needed to be negotiated in the new contract

and to recommend a more sustainable cost distribution.

Evidence

To demonstrate that

the original distribution needed to be reevaluated, the task force gathered

qualitative and quantitative data from participating libraries. Specifically,

their first survey focused on two themes: 1) satisfaction with the current deal

and 2) priorities for the new contract. The second survey included questions

regarding each library’s budget and willingness to renew. (Both surveys are

available in the appendix.)

For a meeting with

representatives from participating libraries, the authors of this article

prepared a presentation to establish shared understanding, facilitate

discussion, and gather feedback for negotiation with the publisher. Talking

points included explanation of the history of the deal, overview of license

agreement terms, and highlights from the survey. By anonymizing the libraries

and their data presented in tables 1 through 4, this case study retains focus

on methodology.

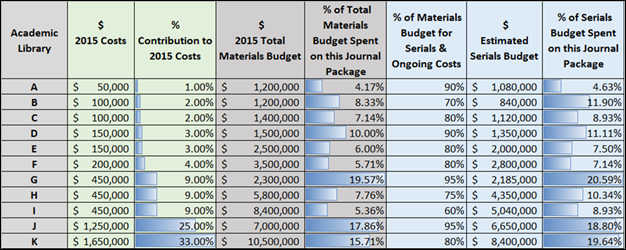

Table 1 includes

qualitative survey data from each library about their total materials budget,

the approximate percentage of their materials budgets that is dedicated to

serials or ongoing costs, and the percentage of the entire materials budget and

serials budget that is spent on this journal package. This illustrated the significant impact of the costs

of this journal package for each library in the consortium.

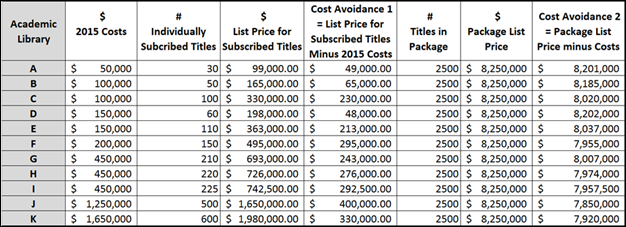

Table 2

shows two different methods of calculating the collective benefit or cost

avoidance from participating in the journal package. Both results demonstrate

that libraries are saving money by participating in this package, but savings

varies by institution. Even though the costs of the journal package are

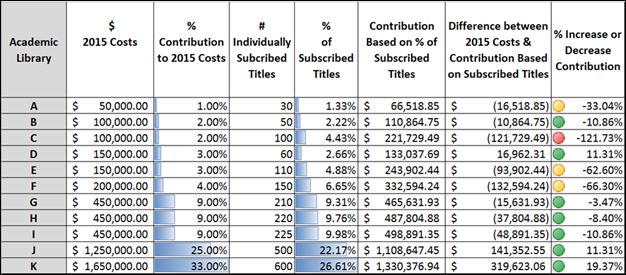

supposed be distributed based on historical spending, Table 3 illustrates how

cost distributions are no longer aligned with the number of subscribed titles

at each library. For example, Library K has 26.61% of the subscribed titles but

pays for 33% of the costs for the package.

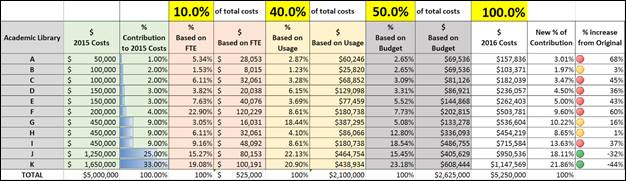

Knowing

that a cost distribution based solely on subscription costs produced

inequitable results, the task force calculated costs using other variables that

are commonly used to determine pricing for academic journals, such as Full Time

Enrollment (FTE) and usage statistics. Table 4 includes data about FTE and

usage at each library to calculate costs based on either of those variables

compared to the current distribution. This yielded similar results for Library

K, which would pay less than their initial contribution if costs were based on

FTE or usage. However, this analysis also revealed that using either FTE or

usage alone could drastically impact a few of the libraries in the deal. For

example, Library F has a very large FTE but relatively low usage, while Library

G is just the opposite situation with a relatively small FTE but substantial

usage.

Table 1

Impact on

Materials and Serials Budgets

Table 2

Cost Avoidance

Table 3

Cost

Comparison

Table 4

Other

Factors for Determining Costs

Using

conditional formatting features available in Microsoft Excel, the authors

demonstrated disparities between libraries both numerically and visually.

Overlaying data bars to represent the proportion of cost that each library

bears quickly illustrated discrepancies. Adding red, yellow, and green icons to

variables, such as cost per use, indicated the relative performance of the

journal package at each library (e.g., green indicated low cost per use and red

indicated high cost per use). Color-coded icons were also used to highlight the

differences between the costs for each model.

The

analysis confirmed that the original distribution gave some libraries

significantly more benefits or less costs than others. It also demonstrated

that relying on a single factor to determine cost would result in similarly

inequitable results. Sharing the results with all of the participating

libraries produced mutual understanding regarding the collective

unsustainability of the package and created the impetus to redefine the

allocation model.

Implementation

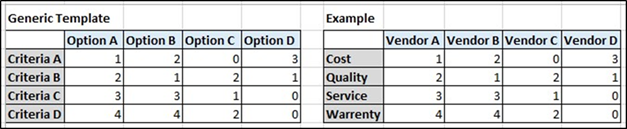

In

business management literature, a classical decision matrix has “options on one

axis and criteria on the other.” See an example in Table 5. When used as an

evaluation, the decision matrix can help leaders make better strategic

decisions by extending the “decision frame beyond the obvious options and

criteria” (Enders, König, and Barsoux, 2016, p. 63).

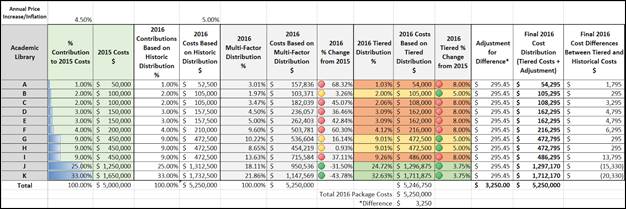

The

authors proposed and the task force agreed to redistribute costs among academic

libraries based on multiple criteria including FTE, usage, and materials

budget. In their modified matrix the decision criteria are presented on one

axis and academic libraries on the other. They determined a percentage of the

total (or weight) for each criteria and used the library’s data to calculate a

percentage of the total for each criteria. The costs are distributed by these

percentages, and the sum determines a library’s share of the total. Once they

identified comparison variables for a weighted decision matrix, they calculated

what a library should pay (Table 6). To ensure that all libraries

remained in the package, they tiered cost distributions into three levels of more

gradual price increases based on what libraries could reasonably pay

(Table 7).

Table 5

Classic

Decision Matrix

Table 6

Multi-Factor

Cost Distribution Using a Modified Decision Matrix

Table 7

Tiered

Cost Distribution

Outcome

Presenting

the evidence in a modified decision matrix expanded the framework for decision

making. This process encourages visualization of options, criteria, and

trade-offs, which can help leaders clarify thinking, engage colleagues, and

promote buy-in from the larger organization (Enders, König, and Barsoux, 2016, p.

68). In the Colorado case study, the modified decision matrix encouraged

libraries to recognize that the historical cost distribution model was no

longer accurate and over time had resulted in some libraries paying a

disproportionately high portion of cost. The Alliance libraries agreed to a new

cost distribution model, and the consortia signed a multi-year journal package

with the publisher. For the CU System, the new cost distribution resulted in

cost savings for Boulder but increases for Auraria and Colorado Springs.

However, the tiered approach kept the costs affordable for all of the CU

libraries, and the net result made the shared purchase viable for the near

future.

Reflection

Consortia

activities are most beneficial when costs and benefits are understood and

shared among all member libraries. The process of surveying participating

libraries, reviewing criteria and variables, and developing cost distributions

should be conducted on a routine basis. The Alliance plans to update the

variables in the decision matrix on a regular basis so that the costs will be

transparent and reflect changes in FTE, usage, or budget for each library.

Conclusion

To ensure better decision making and timely implementation, strategic

business leaders utilize evaluation tools, such as a decision matrices, to

explore options, make choices, and communicate decisions to stakeholders. In

this case study, the authors developed a modified decision matrix with multiple

weighted criteria to redistribute the costs of a purchase that is shared among

consortia of academic libraries. This methodology could be applied to other

scenarios when complex problems require systematic consideration of multiple

criteria and various stakeholders.

References

Colorado Alliance of Research

Libraries. (2016). About. Retrieved 19 March 2017 from https://www.coalliance.org/about

Enders, A., König, A., & Barsoux, J. (2016). Stop jumping to solutions! MIT

Sloan Management Review, 57(4), 63-70. Retrieved from http://sloanreview.mit.edu/article/stop-jumping-to-solutions/

Appendix

Survey Questions

Please note the name of the publisher of the big deal journal package

has been removed from the survey. Minor edits have been made to the surveys for

clarity because it appears here in a different format from the original.

Renewal

Survey, Part 1

Section 1

Please provide feedback about the existing package and license agreement.

1.

Which Alliance library do you represent?

2.

How satisfied are you with the existing journal package?

On a scale between 1

(Dissatisfied) and 5 (Very Satisfied) check one.

3.

How do the following factors impact your satisfaction with the existing

package?

Check one type of impact per

factor: Negatively impact | No impact | Positively impact

a.

Amount of content

b.

Faculty feedback

c.

Student feedback

d.

Librarian feedback

e.

Usability of the platform

f.

Access issues

g.

Usage statistics

h.

License terms

i.

Cost

j.

Are there any other factors that impact your satisfaction that were not

included above?

4.

How likely are you to renew if a new contract was negotiated with the

same or similar terms?

On a scale between 1 (Very

Unlikely) and 5 (Definitely) check one for each scenario.

a.

3 year deal; set at set percent increase

b.

price based on historical title list and transfer titles

c.

access to unsubscribed titles for an additional cost

Section 2

Please provide feedback to help the Alliance negotiate the 2015-2020 contract.

5.

What are some of your priorities for a new contract?

Check one priority level per contract term: Not a Priority | Low Priority |

Medium Priority | High Priority

a.

Reduce our costs

b.

Cap annual increases

c.

Increase amount of content

d.

Create a new title list

e.

Break up the Big Deal and subscribe to individual titles

f.

Create uniform access across Alliance libraries

g.

Secure perpetual rights/post-cancellation access

h.

Add license terms for ADA compliance

6.

How do the following factors influence your decision to participate in

the Alliance package?

Check one level of importance per

factor: Not important | Somewhat important | Very important

a.

Current budget

b.

Projected/expected annual budget increases

c.

Impact of cancellation on ILL

d.

Impact of cancellation on collection size

7.

What factors should be considered to determine our costs for the new

Alliance package? The following factors have traditionally been used to

determine prices for other journal packages or databases. Check all that apply

to your library.

a.

FTE

b.

Carnegie Classification

c.

Number of faculty (total or within certain departments)

d.

Usage

e.

Historical spend for titles

f.

List Price

g.

Other: Please provide details.

8.

Are there other factors to determine price that were not included above?

9.

Would you be interested in exploring different acquisition models for

this content during the negotiations? Check one level of interest per

acquisition model: Not interested | Somewhat interested | Very interested

a.

Evidence-based model

b.

Token-based model

c.

Pay-per-view model

d.

Database subscription model (no title lists, no perpetual access)

e.

One-time purchase model

f.

Other model, to be determined

10.

Are there other acquisition models that should be explored but were not

mentioned above?

11.

Are you interested in adding/integrating other publisher products into

this renewal?

Check one level of interest per product: Not interested | Somewhat interested |

Very interested

a.

Product A

b.

Product B

c.

Product C

12.

Are there other publisher products that should be considered during this

negotiation?

13.

Do you have questions for the publisher?

14.

Do you have any comments or questions for the negotiating team?

Renewal

Survey, Part 2

1.

Which Alliance library do you represent?

2.

What is your FY2014-15 budgeted appropriation for library materials

(excluding gifts, grants, external funding)?

3.

What percent of your library materials budget is typically allocated to

serials/ongoing costs?

a.

30-40%

b.

40-50%

c.

50-60%

d.

60-70%

e.

70-80%

f.

80-90%

g.

90-100%

h.

Other: Please provide details.

4.

If we negotiated another 3-year deal with capped annual increases, at

what percentage increase would you renew? Check all that apply

a.

Below 3.0%

b.

3.5%

c.

4.0%

d.

4.5%

e.

5.0%

f.

Other: Please provide details.