Using Evidence in Practice

A Mixed Methods Approach to Iterative Service Design of an In-Person

Reference Service Point

Kyla Everall

User Services Librarian

University of Toronto Libraries

Toronto, Ontario, Canada

Email: kyla.everall@utoronto.ca

Judith Logan

User Services Librarian

University of Toronto Libraries

Toronto, Ontario, Canada

Email: judith.logan@utoronto.ca

Received: 10 July 2017 Accepted: 6 Oct. 2017

2017 Everall and Logan. This

is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0 International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

2017 Everall and Logan. This

is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0 International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

Setting

The University of

Toronto is Canada’s largest university, with an enrolment of over 88,000

students (University of Toronto, n.d.). Currently

ranked fourth by the Association of Research Libraries, with an annual total

expenditure of $72 million USD (ARL, 2016), we have 44 libraries spread over

three campuses.

Problem

Our largest library is a 14-floor building located in the center of our

downtown campus.

When John P. Robarts Library was first opened in 1973, the reference

desk on the fourth floor was conveniently located next to the card catalogues

and near the main entry point to the book stacks. The card catalogues are long

gone and the ground floor is now open for stacks access, but the reference desk

has remained nearly unchanged physically. Likewise, our service model remained

stable for decades. Two or three library staff members sat behind a large

wooden desk from mid-morning to early evening. Shifts were primarily staffed by

librarians with support from student librarians trained in the department. Our

schedule called on librarians regardless of specialized expertise; when our

department incorporated government information librarians in 2009, they, too,

served on the reference desk.

Figure 1

“John P. Robarts Library” by Jeff Hitchcock on

Flickr. Retrieved from https://www.flickr.com/photos/arbron/29821692490

Over the last ten years, student feedback collected through LibQUAL+ and other means has identified that Robarts is a

confusing and intimidating library to navigate. Service provided by staff

throughout the building did not always meet students’ expectations. We

partially addressed this longstanding problem in 2015 when we added a roving

service of student library assistants whose primary roles were to direct users

to the correct location within the building and to troubleshoot problems with

self-service machines such as printers. The usage statistics for this service

showed the most traffic on the second floor of the building. This made sense

considering that there were no library service points or staff members on this floor

besides one entrance monitor who monitors the security gates and enforces our

food policy.

We hoped that redesigning our outdated reference desk could also address

gaps in Robarts’ perceived user-friendliness.

Evidence

We approached this problem within a service design framework. A

relatively new method in libraries, service design is a “holistic, co-creative,

and user-centered approach to understanding customer behavior for the creation

or refining of services” (Marquez & Downey, 2015, para. 7). The aim is to

use lightweight research methods to gain insights and make decisions, rather

than conduct exhaustive studies of the problem (Polaine,

Løvlie, & Reason, 2013). Service design also

encourages prototyping, allowing service providers to test their ideas without

a large investment of resources (Polaine et al.,

2013).

Looking at our reference desk statistics emphasized just how much usage

patterns have changed over time. Our interactions declined by more than 50%

since the 2009-2010 academic year (Figure 2). Demand

for the service was clearly changing. We asked ourselves, if in-depth reference

expertise was only needed in about a third of the interactions currently on the

desk, was there a better way to deploy our staff without sacrificing quality of

service?

Figure 2

Reference desk interactions from 2009-2016.

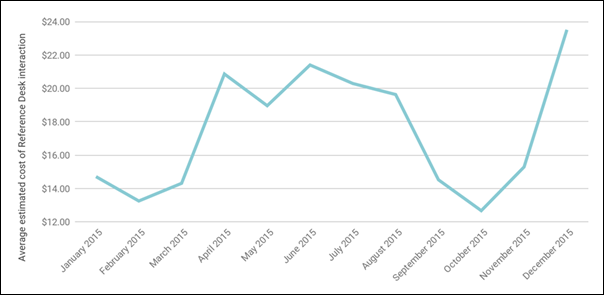

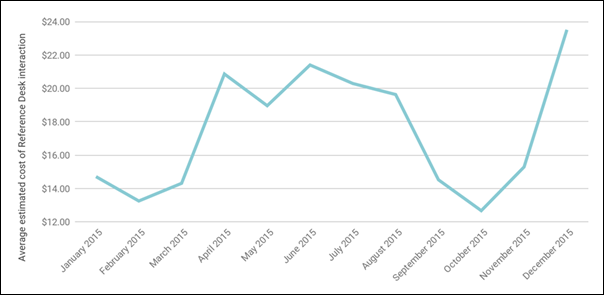

Figure 3

Average estimated cost of reference desk interactions per month.

To investigate the effectiveness of our service model’s staffing mix, we

did a rough cost analysis to estimate the cost per interaction (Figure 3). This

analysis indicated that there were times of the year when our service model was

more cost effective than others. We planned to use this information when

designing the schedule of our redesigned service point.

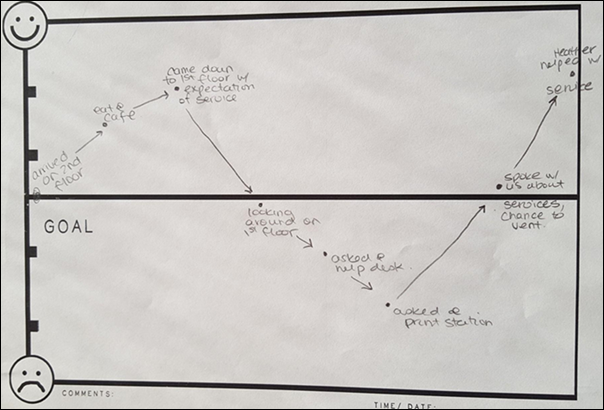

Figure 4

An example of a completed journey map for a

student who wanted to use scanners.

Further probing this issue, we conducted focus groups with our student

librarians to assess their training and identify gaps in their knowledge. They

reported high levels of confidence in answering general research questions.

Referrals and questions that require organizational knowledge were their

biggest challenges. This indicated to us that, once trained, our student

librarians might be able to provide the bulk of staffing at our new service

point if properly supported.

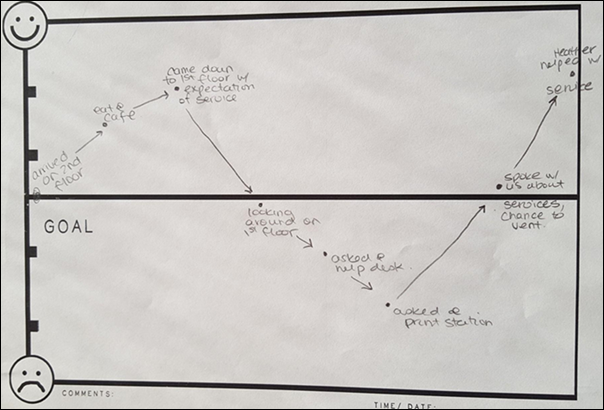

We also conducted a journey mapping research project to help us

understand how our users were moving through the building. We surveyed users as

they left the library about their goals during their visit. We then asked for a

step by step breakdown of how they tried to achieve their goals and how they

felt during each step (Figure 4).

We found only 35% of users came to the library with scholarly goals.

This category included using print resources and working with librarians.

Respondents reported two pain points that had previously surfaced in LibQUAL+: navigating the building and unhelpful

interactions with staff.

Implementation

We moved our reference desk to the second floor of the building and

rebranded it the “Ask us! desk” with a large sign

placed next to it. All staff wore blue vests emblazoned with an information

symbol while working on the service desk for the first eight months.

We purchased a variable height standing desk on castors with the

intention of moving it around the floor to identify the ideal location, but we

discovered that the wireless service was too unreliable. Instead, staff

connected the desk’s laptops to a nearby LAN network. Happily, this was near

the entrance to the cafeteria and a very busy coffee shop. We forwarded our

reference desk’s extension to a cell phone so we could continue to offer

telephone service, and issued earbuds to staff so they could be hands free

while serving users on the phone.

A team collaboration and chat tool called Slack (https://slack.com/) was already in use

in other units of our library, so we used it to facilitate communication

between staff members at the Ask Us! desk and the rest

of the department. We created a Slack “team,” which is similar to a message

board, and invited as many public service staff members in the building as we

could in hopes of increasing communication between service points.

Once we were physically set up on the second floor, we began to adjust

our staffing mix. We stopped scheduling our government information specialist

librarians on the desk as their expertise is in high demand on other reference

channels. We also stopped scheduling two librarians at the same time; the

maximum complement became one student librarian and one librarian. Once our

student librarians were trained, on boarded, and sufficiently mentored, we

moved to a backup model where the librarian assigned to the shift remained in

their office and stayed in communication with the student librarian on shift

over Slack. If the shift became busy or the librarian's expertise was needed,

the student librarian would ask the librarian to come down to help over Slack.

Outcome

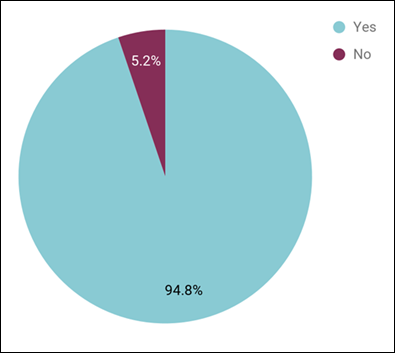

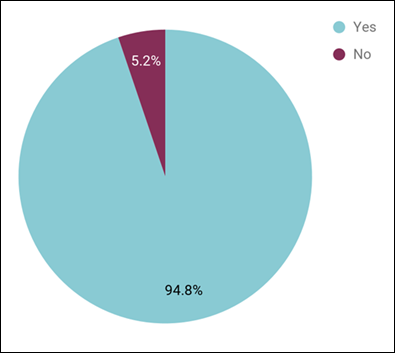

To see if the new model was working for our users, we conducted exit

surveys in the fall and winter semesters. Respondents reported high levels of

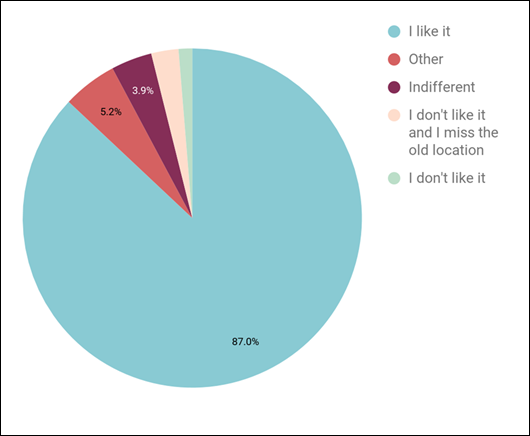

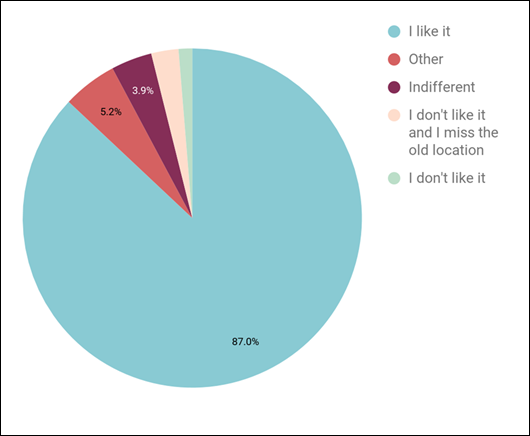

satisfaction with the service that they received at the desk (Figure 5), and

87% of respondents liked the location (Figure 6). Only 4% of respondents had a

negative impression of the location, and the remaining 9% were either neutral

or responded in a way that was not readily classifiable (e.g., “I wish we had a

desk like this on every floor”). We also discovered that the blue vests were

not significantly more important to our visibility than signage or staff

demeanor (Figure 7).

Figure 5

Were you satisfied with the help that you received today? (n=77)

Figure 6

What do you think of the current Ask Us! desk

location? (n=77)

Figure 7

What was the main thing that made you think that you could get help at

this desk? (n=77)

Figure 8

Reference desk/Ask Us! desk interactions,

2009-2017.

We monitored our usage statistics to see what impact the new location

would have. While we saw an overall increase in usage, the bulk of the

questions were directional (Figure 8). Brief and in-depth reference questions

declined more than in past years, suggesting that we need to reassess the new

model to ensure that it is attracting in-depth reference appropriately.

We also repeated the journey mapping exercise to gauge if the new desk

had any impact on users’ holistic experience of the library. There was almost

no change in the majority of pain points reported, but this time there were no

complaints about library staff. There are too many variables to attribute this

positive outcome to solely our service, but it is an encouraging sign.

Throughout the implementation process, we consulted the staff working on

the desk about the new model. Some staff voiced concerns about the blue vests.

They felt strongly that wearing the vest made them look unprofessional, and

reported that staff from other units had made comments to this effect. Since we

learned from the exit surveys that the vests were not significantly more

important to identifiability than other factors, we replaced the vests with

lanyards.

Librarians reported noticeable improvements in their mentoring

relationships with student librarians. Due to the layout of the new desk, we

worked shoulder to shoulder with them, creating more feelings of teamwork and

more collegiality than in previous years. We also noticed that the student

librarians’ skills developed significantly faster under the new model.

Reflection

By considering a variety of data sources when redesigning our service

point, we developed a model that better fit our users. Our intention was always

to do just enough research to allow

us to produce a prototype which we could refine after the initial

implementation. When we encountered unforeseen obstacles, such as poor Wi-Fi,

we reconfigured the service. Rather than derailing the project, we were

prepared to address issues as they arose, ultimately resulting in a more

responsive, flexible service.

Prior to this project, the prevailing organizational narrative was that

service changes involving staff would be met with overwhelming resistance. A

benefit of launching our new service model as a work in progress was more staff

engagement and less resistance than anticipated. This prototyping approach

signaled to staff that their feedback was not only tolerated, but necessary to

the success of the project.

References

Association of Research Libraries. (2016, August 14). Spending by university research libraries, 2014-15.

Retrieved from http://www.chronicle.com/interactives/almanac-2016?#id=65_416

Marquez, J., & Downey, A. (2015). Service design: An

introduction to a holistic assessment methodology of library services. Weave: Journal of Library User Experience, 1(2).

http://dx.doi.org/10.3998/weave.12535642.0001.201

Polaine, A., Løvlie,

L., & Reason, B. (2013). Service design: From insight to implementation. Brooklyn, N.Y.:

Rosenfeld Media.

University of Toronto. (n.d.). Quick facts.

Retrieved from https://www.utoronto.ca/about-u-of-t/quick-facts

![]() 2017 Everall and Logan. This

is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0 International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

2017 Everall and Logan. This

is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0 International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.