Research Article

User-focused, User-led: Space Assessment to Transform

a Small Academic Library

Christina Hillman

Assessment & Online

Program Librarian

Lavery Library

St. John Fisher College

Rochester, New York, United

States of America

Email: chillman@sjfc.edu

Kourtney Blackburn

Access Services Librarian

Lavery Library

St. John Fisher College

Rochester, New York, United

States of America

Email: kblackburn@sjfc.edu

Kaitlyn Shamp

Student Researcher

St. John Fisher College

Rochester, New York, United

States of America

Email: kks04047@sjfc.edu

Chenisvel Nunez

Student Researcher

St. John Fisher College

Rochester, New York, United

States of America

Email: cn01722@sjfc.edu

Received: 13 July 2017 Accepted:

23 Oct. 2017

![]() 2017 Hillman, Blackburn, Shamp, and Nunez. This

is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

2017 Hillman, Blackburn, Shamp, and Nunez. This

is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

Abstract

Objective

– By

collecting and analyzing evidence from three data points, researchers sought to

understand how library spaces are used. Researchers have used results for

evidence based decision making regarding physical library spaces.

Methods – Undergraduate researchers, sociology faculty, and librarians used

mixed-methods to triangulate findings. Seating sweeps were used to map patrons’

activities in the library. Student-led focus groups discussed patterns of

library use, impressions of facilities, and library features and services. The

final step included a campus survey developed from seating sweeps and focus

group findings.

Results

– Seating

sweeps showed consistent use of the library's main level Learning Commons and

upper level quiet spaces; the library’s multipurpose lower level is

under-utilized. Students use the main level of the library for collaborative

learning, socializing, reading, and computer use. Students use the upper level

for quiet study and group work in study rooms. Focus group findings found

library use is task-specific. For example, a student may work with classmates

on a project using the main level Learning Commons during the day, and then

come back at night to use the quiet floor for test preparation. Survey

responses highlighted areas in which the library is deficient. For example,

respondents cited crowdedness, noise levels, and temperature concerns.

Conclusion

– These

data offer empirical evidence for library space needs. Some data aligns with

previous space studies conducted at this library: access to power outlets,

lighting, noise, and an outdated environment. Evidence also supports anecdotal

concerns of crowding, graduate students lacking designated study space, and the

need for quiet study space away from

group study space.

Introduction

Established

in 1975 as the sole library for the St. John Fisher College, Lavery Library

serves a campus of approximately 3800 students, including undergraduate,

masters, and doctoral. The College is primarily an undergraduate institution

with a growing graduate population. At the same time, the library has witnessed

a slow but dramatic shift in the way users work in physical library spaces. The

library uses daily headcounts and gate counts to improve library spaces. The

library also conducted several space studies over the past decade to inform

small-scale physical changes and better accommodate changing user needs.

Renovations since 2012 include a Learning Commons, the creation of a

multi-purpose space (Keating Room), a space with cafe-like seating, and

additional outlets. Through strategic weeding, the library has enlarged study

spaces. Recent changes include the addition of easily movable tables and

soundproofing quiet floor doors. These changes are welcomed by the campus community,

but formal and informal feedback from the students provides a clear and

consistent message: the library must continue to keep pace with their changing

space needs in order to maintain a high standard of service.

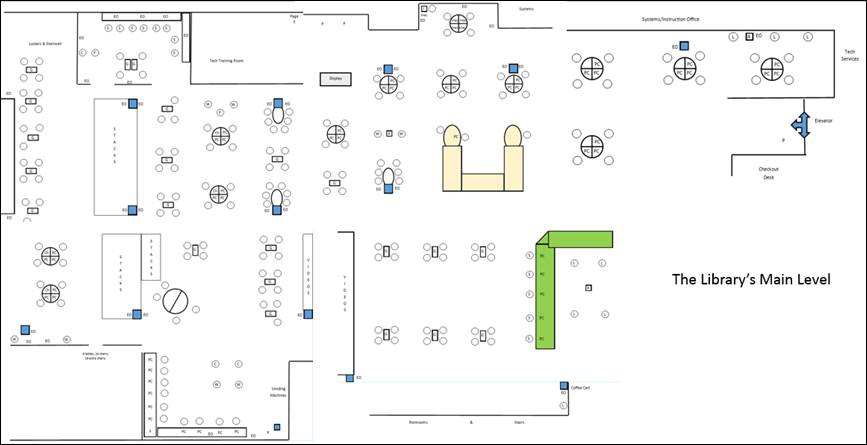

The

library is three levels, with users entering on the second (main) level. This

level houses the Keating Room and Learning Commons, which includes group

workstations with large monitors, desktop computers, and a variety of tables

and chairs for groups and individuals. The lower level includes group work

tables and two classrooms, one of which is a computer lab. The upper level is

the quiet floor, the only floor with a noise policy. There is a variety of

seating, including individual study carrels, small and large tables, individual

and group study rooms, and two reservable meeting spaces. The library is also

home to other campus departments (e.g., Career Center, Academic Opportunities

Program Office, Office of Information Technology, and others), which were not a

focus of this study.

Literature

Review

Library as Place

With

a shift from print to electronic collections, libraries have reinvented

themselves as flexible learning spaces with a focus on community. The phrase library as place best describes how

students use the library as a flexible, dynamic space adaptable for changing

needs (Freeman, 2005). Other studies discuss how students continually remake

spaces to fit their needs to support their learning (Fallin, 2016; Hanson &

Abresch, 2016). Montgomery (2014) refers to the library as a place for informal

learning, where students can set their own goals and determine their needs. The

library is thought of for its study spaces and less for services and

collections (DeClercq & Cranz, 2014; Hall and Kapa, 2015). A place to

gather and have conversations, according to Oldenburg (1997), is an important

part of learning; the library has begun to be this place. As a result of this

flexibility and community building, academic library users, particularly

students, see the library as a “third space” (DeClercq & Cranz, 2014)—a

place neither classroom nor residence hall. Academic work and socializing takes

place within third spaces, and “library as place” fills the need for this third

space.

Space Attributes

Whether

it is quiet study space or an open meeting space, the reasons how and why users

select library spaces largely depend on individual needs and activities (Cha

& Kim, 2015; İmamoğlu & Gürel, 2016; Khoo, Rozaklis, Hall, Kusunoki,

& Rehrig, 2014; Montgomery, 2014; Vaska, Chan, & Powelson, 2009).

Research focusing on students’ requirements of library spaces reveal common

themes: more natural light, larger or more tables and chairs, and more outlets

(Andrews, Wright & Raskin, 2015; DeClercq & Cranz, 2014; İmamoğlu &

Gürel, 2016; Khoo et al., 2014; Montgomery, 2014; Vaska et al., 2009). Library

spaces must also accommodate simultaneous device use by students (Ellison,

2016; Ojennus & Watts, 2017). Similarly, research indicates the need for

collaborative spaces that can accommodate a variety of technologies (Andrews et

al., 2015; Given & Archibald, 2015; Freeman, 2005; Lux, Snyder, & Boff,

2016). At the same time, Goodnight and Jeitner (2016) focus on the desire for

quiet, because students “come to the library searching for spaces that are

quiet, where they can settle down to read and study and write their papers in

silence, without distractions . . .” (p. 219) from others. Similar research

also notes individual study carrels and quiet spaces are valued (Hall &

Kapa, 2015; Montgomery & Miller, 2011; Ojennus & Watts, 2017; Oliveira,

2016).

Group Study and

Non-Quiet Spaces

Non-quiet

space in the library—for example, group study rooms and flexible learning

spaces—are ideal for many library users, as indicated by Freeman (2005). Recent

literature shows the need for more of these spaces, and that students respond

positively to redesigns which provide more flexible learning and group study

spaces (Cha & Kim, 2015; Given & Archibald, 2015; Khoo et al., 2014,

Montgomery, 2014). Studying alongside others provides visual and social

pressure for students, furthering the communal space (Andrews et al., 2015).

There is a need for libraries to create spaces where users can collaborate,

socialize, and study alone and alongside others (Andrews et al., 2015; DeClercq

& Cranz, 2014; Freeman, 2005; Montgomery, 2014; Montgomery & Miller,

2011, Ojennus and Watts, 2017).

Research

indicates students use quiet areas to accomplish serious work (e.g., to study

for exams or write papers) (Cha & Kim, 2015; DeClercq & Cranz, 2014;

Freeman, 2005; Khoo et al., 2014). Even during individual study, students often

indicate their desire to be near others studying (Andrews et al., 2015;

Applegate, 2009; Goodnight & Jeitner, 2016; Hall & Kapa, 2014; İmamoğlu

& Gürel, 2016; Montgomery, 2014). Yet, students still desire ample personal

space, feeling a space is full when 40-50% of seats are occupied (Applegate,

2009; İmamoğlu & Gürel, 2016; Khoo et al., 2014). Physical dividers would

allow users to delineate personal space and minimize distractions so that they

can work most effectively (İmamoğlu & Gürel, 2016).

Aims

The

purpose of this study is to examine and analyze how students use library

spaces. Collected evidence will be used to plan space renovations, both small

and large. Additionally, collected evidence will improve understanding of what

works, what does not work, and what is needed in the library.

Methods

This

study used multiple methods to triangulate findings and provide a clearer

understanding of how library spaces are used. Methods included seating sweeps,

focus groups, and survey. Research was conducted with Institutional Review

Board (IRB) approval.

Seating Sweeps

Seating

sweeps were based on Given and Leckie’s 2003 study, “’Sweeping’ the Library:

Mapping the Social Activity of the Public Library.” Librarian researchers

trained three permanent library staff members to assist with completing sweeps.

Data was collected floor-by-floor with printed maps and a clipboard (See

Appendix A). They were conducted three times a day for two non-consecutive

weeks during spring 2016. The first sweep took place in February, just before

spring break; the second was in April, a few weeks before finals. Sweeps were

conducted at 9 A.M., 1 P.M., and 8 P.M. to create a snapshot of user behaviours

throughout the day, and took between 15 and 60 minutes depending on busyness.

Staff recorders noted user activities and personal items, such as use of a

desktop, laptop, cell phone, tablet, or whiteboard; and if they had food or

drink. Recorders also marked if users were conducting group work, note-taking,

reading, sleeping, talking, or performing other noteworthy activities. For

instance, recorders captured when individual users occupied entire tables

intended for multiple people, or when users dragged cords across aisle ways to

reach outlets. Interested in users’ willingness to move larger furniture,

librarian researchers purposely left furniture placement off the map in the

multi-purpose Keating Room so recorders would be able to draw changes to

configurations of the space. To minimize intrusiveness, recorders maintained a

reasonable distance from users. The clipboard also included a sign stating that

a library space study was in progress in order to inform users but hopefully

not discourage or change user behaviours. Data from the coded maps were entered

into a Google Form for analysis.

Focus Groups

After

seating sweeps were completed, student researchers and sociology faculty

advisers joined the research team. Faculty advisers trained student researchers

to conduct focus groups. Focus groups

were organized by class year (9 freshmen, 9 sophomores, 10 juniors, 8 seniors,

2 masters, and 3 doctoral students) totaling 41 participants. Student

researchers recruited undergraduate participants by invitation; liaison

librarians recruited masters and doctoral participants by emailing targeted

classes. Participants were offered pizza and the chance to win a prize as an

incentive. The research team developed questions based on past local space

surveys and sweeps data. Librarian researchers and faculty advisers were not

present at the focus groups in an effort to minimize their influence on

participants’ responses. Each undergraduate group was asked the same set of

questions; these questions were altered slightly for masters and doctoral

students. Student researchers took notes of participants’ responses, and after

the focus groups were completed, the research team came together to analyze

findings. Focus group data were reviewed for common themes by each researcher

independently, and schemas were developed as a team to help inform survey

development.

Survey

The

research team developed questions based on findings from seating sweeps and

common themes from library focus group data. Qualtrics was used to build and

distribute the completed survey (See Appendix B). As with many institutions,

students have survey fatigue on our campus. In order to keep the survey short

and increase response rate, the research team opted not to include demographic

information in the survey. Prior to distribution, faculty advisers and student

researchers piloted the survey with a small group of undergraduates.

Researchers decided to exclude masters and doctoral students due to their low

participation in focus groups and a lack of relevant data.

All

undergraduates (N=2948) received the survey via email. To improve response

rate, the survey was emailed to students through the well-recognized and

respected Student Government Association (SGA). Respondents completed the

survey anonymously, with the caveat that if they wished to enter a drawing for

a $100 Amazon gift card, they needed to provide their name and email address. A

separate survey allowed respondents to enter the drawing, which allowed the

research team to maintain confidentiality of responses. The survey ran for

three weeks with two reminder emails, sent through the Qualtrics platform, to

those who had yet to complete the survey. The overall response rate was 12%.

Results

Seating Sweeps

Findings

from seating sweeps helped visualize occupancy patterns and user behaviours.

Existing library data shows the busiest time is the 1 P.M. hour Monday-Friday,

which is consistent with seating sweep findings. Data from sweeps revealed the

main level to be the busiest, followed by the upper level (see Table 1). Tables

meant for 4 people were observed with only 1 person spread over the entire

surface 12% of the time, effectively making the space fully occupied. This data

is consistent with survey findings regarding crowdedness. At the same time, the

lower level occupancy rate was less than 1% during sweeps, despite being a

non-quiet space.

Behaviours

recorded during sweeps indicated the library is a multipurpose, adaptable

space, similar to other research. A key finding from the sweeps showed 10% of

users were settling in or making themselves at home in their claimed spaces:

using bean bag chairs to get comfortable, adjusting lighting, taking off their

shoes, sleeping, and abandoning belongings for extended time. Findings from

sweeps also observed 40% of users eating or drinking, another indicator of the

library being a flexible third place. Data also showed users crowding around a

single computer monitor for collaborative work rather than making use of

collaborative group workstations and their larger monitors, with the latter

noted only three times. Students made frequent use of flexible furniture in the

library, especially in the Keating Room. Findings from sweeps showed students

use the movable whiteboards for their intended use (studying), but

interestingly, also as barriers to create privacy. Observed behaviours related

to technology confirmed informal feedback regarding the need for more outlets

and power.

Table

1

Combined Average Occupancy of Patrons by

Floor during Seating Sweeps

|

|

9a.m. |

1p.m. |

8p.m. |

|

Lower

Level |

2.5 |

9 |

11.6 |

|

Main

Level |

24 |

91.1 |

67.6 |

|

Upper

Level |

12.3 |

42.6 |

33.1 |

During

sweeps, 41.5% of users were recorded simultaneously using at least two

electronic devices, creating a higher demand for power and technology options

in the library.

Focus Groups

Findings

from focus groups provided better understanding of what users think about

library spaces, including their intended use and desire for these spaces.

Common uses for the library included studying, computer use, printing, and

working on group projects. These results were common among all focus groups.

Common responses when asked about well-liked library services and features

included: interlibrary loan, librarians and the Research Help Desk, and group

workstations for easier collaboration. When asked about services or features

they would like to see added, common responses included a stress relief room

with nap pods, extended hours, and additional quiet floor study rooms.

Participants requested smaller, 1-2 person tables for independent work, stating

once they set up at larger tables other students appear dissuaded from joining

the table. Participants suggested extended hours, with a few participants

stating the library should stay open 24 hours or at least until 3 A.M.

Findings

revealed differences in how undergraduate commuters and residents use the

library. Commuters indicated coming to the library most often between classes

to connect

with

friends, not to engage in serious work. As with many participants, commuters

mentioned choosing somewhere on the quiet level when coming to the library for

serious work. Residents use dorm lounges or their rooms for work and use the

library for printing or socializing. For group work and projects, both

commuters and residents commonly use library spaces, but stated the lack of

privacy on the main level and the noise policy on the upper level can be

frustrating. Undergraduate students mentioned the breakout rooms available in

other buildings are ideal spaces for this type of work.

Focus

group questions for masters and doctoral students differed slightly than those

asked of undergraduates. These participants’ responses revealed differences in

library use, including primarily using the library for research purposes. Most

stated using librarians as helpful resources when conducting research, and were

more emphatic in their responses regarding use of the Research Help Desk. Two

participants completed undergraduate degrees at St. John Fisher College, and

indicated their library use as graduate students is much more academically

oriented.

Survey

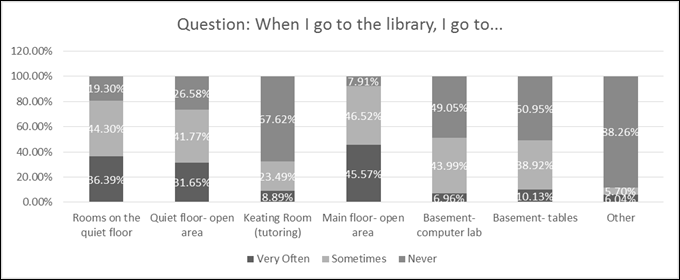

The

survey provided data for how undergraduates self-reported using library spaces

in relation to focus groups and sweeps data. Respondents reported using Main

Level – open area and the Keating Room (tutoring) spaces 45.57% and 8.89%,

respectively, “very often”. Respondents

self-identified using quiet floor open areas and study rooms “very often”

31.65% and 36.39% of the time, respectively. The main level is the most

self-identified used space, with the upper level spaces closely following.

Survey results find the library’s lower level (basement) is underutilized, with

basement – computer lab and basement – tables “never” being used 49.05% and

50.95% of the time, respectively. Figure 1 provides a breakdown of library

spaces and their frequency of use by respondents. Monday-Thursday and Finals

Week are the most popular times in the library: 45% of users stated they come

to the library “very often” Monday-Thursday, and 57% of users indicated that

they come to the library “very often” during Finals Week. Nearly 50% of

respondents think the library needs extended hours, which is similar to

findings from focus groups; however, just under 40% of individuals indicated

coming to the library “very often” in the evening.

Figure

1

Responses

to survey question: When I go to the library, I go to….

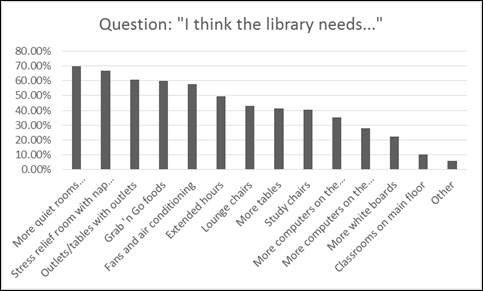

In

addition to revealing what spaces respondents reported using most frequently,

they also shared which spaces are deficient (see Figure 2). As previously

noted, the quiet floor and its private rooms are extremely popular, and

unsurprisingly, 69% of respondents requested additional private rooms. Also

unsurprisingly, respondents said the library needs more outlets (60%) and tables

(41%) throughout the library. The need for more outlets and tables has a strong

relationship to findings of computer use and group work, with 52% of

respondents using computers and 64% of respondents “sometimes” conducting group

work in the library. Overall, respondents are mainly interested in conducting

academic-related activities in the library. Even so, a high percentage of

respondents requested the addition of stress-relief features such as nap pods

and massage chairs, as well as Grab ‘n Go foods.

Survey

results regarding noise levels and temperature shed light on students’

individual perceptions of spaces. When asked if the library is “too noisy,” 62%

of respondents indicated the library was “sometimes” too noisy, which parallels

findings of crowdedness, as 64% of respondents indicated the library was

“sometimes” too crowded. Despite the majority of respondents indicating that

the library is “sometimes” too noisy and “sometimes” too crowded, noise and

crowdedness may not always be related. This lack of correlation may be due to

the time of day a student uses the library. For example, the 1 P.M. hour is

extremely crowded and noisy, whereas the 8 P.M. hour might be crowded but

relatively quiet. Regarding temperature, when responding to the statement “I

think the library needs . . .” with a list of options users could check (see Figure

2), 58% selected “Fans and air conditioning.” There was some relationship

between this finding and the library being too hot: 34% felt the library was

“very often” too hot and 44% felt the library is “sometimes” too hot, while 64%

felt the library is “never” too cold.

Figure

2

Response

to survey question: “I think the library needs . . .”

Discussion

Library as Place

Common

themes from space-related literature are echoed in this study’s findings. As

with Freeman (2005), Lavery Library created flexible spaces, providing

moveable, lightweight furniture for users to create their ideal study

environments. During sweeps users were consistently observed moving tables,

chairs, and whiteboards to create such environments, leading researchers to

infer users are comfortable enough in the library to make spaces fit their

needs (Montgomery, 2014). Further, observed users exemplified “library as

place” by lounging in beanbag chairs, adjusting lighting in study rooms, taking

off shoes, sleeping, and using headphones. Whether headphones were used as

noise dampening or for watching videos was not captured, and focus group

participants only mentioned their appreciation of headphones available for

checkout and earbuds for purchase at the Checkout Desk. Additionally, observations

suggested a high level of comfort in the library and with each other; users

frequently abandoned belongings. This may also be a means to save their spaces

when the library is crowded.

Students

make use of flexible learning spaces, moving tables and chairs as needed to

accommodate their needs. A good example of this is students consistently moving

tables and chairs in the Keating Room. The maps used for the sweeps

purposefully left furniture placement off the map so recorders would be able to

draw daily configurations of the space. While the space never changed

dramatically, there were small changes, including the rolling white boards. The

idea of collaborative, flexible study spaces, where students are able to work

together, have been the main focus of recent updates to library spaces over the

last 10 years. As other researchers have noted, these spaces support student

learning, including collaboration, social learning, and alone-together study

(Cha & Kim, 2015; Given & Archibald, 2015; Khoo et al., 2014; Ojennus

& Watts, 2017). Interestingly, focus group participants repeatedly said

they like the group work stations for completing group work, yet users were

rarely using these tables as intended during sweeps. More often, users at these

tables used the integrated outlets to power their laptops, leading the research

team to believe students like these tables more for their outlets and less for

the ability to share a screen.

Demand

for a stress relief room and nap pods signals that while users come for serious

work, they feel the library should, or could, serve as a comfortable, relaxing

environment, indicative of the “third space” discussed by DeClercq and Cranz

(2014). Focus group and survey results revealed undergraduates frequently come

to the library before classes or after dinner for printing and academic work,

while they come in between classes for group work and socializing. Despite low

participation in focus groups, graduate students unsurprisingly indicated their

use of library spaces is almost wholly academic, citing a need for quiet and a

fondness for academic-oriented library services. Students’ motivations for

library use need to be considered for any library planning renovations and new

services, especially when faced with increasingly diverse student populations.

This is something Lavery Library must take into account given our increasing

graduate population.

Space Attributes

Students

use library spaces for a variety of reasons; most commonly, data revealed users

come to the library for academic work. Space needs differ among users and are

often task-dependent, with both individual and group work requiring a variety

of furniture options. Independent of group or individual study spaces, more

table and seating options are a common theme within focus groups and survey

findings, aligning our students’ desires with other research on space

attributes (Cha & Kim, 2015; İmamoğlu & Gürel, 2016; Khoo et al., 2014;

Khoo, Rozaklis, Hall, & Kusunoki, 2016; Montgomery, 2014; Vaska et al., 2009).

Regardless of space preferences (i.e., quiet vs. non-quiet), users consistently

and whenever possible need additional outlets, aligning with research regarding

the need for additional power to accommodate technologies (DeClercq &

Cranz, 2014; İmamoğlu & Gürel, 2016; Khoo et al., 2014; Montgomery, 2014;

Vaska et al., 2009). The need for more outlets, aside from the building’s age,

may stem from multiple, simultaneous device use (i.e., laptop, cell phone,

desktop) found in sweeps data. Builders in 1974 could not have predicted the

pervasiveness of technology today, but future renovations must address power

capacity.

The

library’s main level is a mix of desktop computer pods, group workstations,

lounge furniture, and other flexible spaces, and is frequently abuzz with

students working on group projects, studying together, and socializing. It is

also where the Checkout Desk and Research Help Desk are located; these two

desks are frequently busy with library users seeking assistance with research,

utilizing technology, checking out materials, and performing other activities.

The main level is certainly what Freeman (2005) would consider “the sound of

learning” (p. 5), with sweeps, focus groups, and survey responses indicating

the library is used frequently for group work. However, the main level does

have its drawbacks for group work. For example, it is possible group

workstations are not as frequently used as intended due to a lack of privacy.

Based on focus group findings, group workspaces should be addressed in library

renovations, specifically the addition of break-out rooms or other semi-private

spaces with soundproofing.

Particularly

surprising throughout all phases of research is the under-use of the lower

level. This is a mixed-use, flexible space where talking is allowed, but is

typically quieter than the main level. Occupancy during sweeps was less than 1%

and students rarely mentioned the lower level during focus groups. This trend

continued in survey responses, with approximately 50% of respondents “never” going

to any lower level spaces (i.e., “Basement- computer lab” and “Basement-

tables”). Understanding why students are not using this available space would

be extremely valuable. As Khoo et al.(2016) mentions, spaces without defined

use conventions are considered full when they are relatively unoccupied, as

individuals are unlikely to join a space already occupied by another

individual. In the case of the lower level, this might be doubly true, as the

classrooms on this level are not commonly used outside of instruction and

students may be unaware of when they are able to, or not able to, use these

rooms. Other factors contributing to underuse could be the lack of natural

lighting, undefined policies regarding noise, and temperature. The only

available lighting in the lower level is fluorescent lighting; there are no

desk lamps and only one semi-hidden space with windows. While the only

designated quiet space in the library is the upper level, the lower level is

much quieter than the main level. Lastly, underuse may be a result of

temperature variance, something noted in the focus groups and survey findings.

As

with other research (Cha & Kim, 2015; DeClercq & Cranz, 2014; Freeman,

2005; Khoo et al., 2014, Khoo et al., 2016), our students are looking for a

quiet space to “get serious” (e.g., write research papers). This is especially

true for masters and doctoral students, including one doctoral student wishing

the library would be more like a neighboring academic library, where the entire

space is quiet. This population’s need for quiet space may stem from different

academic requirements (e.g., dissertation research), or the need for quiet

space outside of home or work. Not surprisingly, many undergraduates indicated

a desire for quiet space as well, specifically when concentration is required,

as the library main level can be noisy. What is particularly interesting,

especially in lieu of survey results, is upper level sweeps have only about 20%

occupancy, even during peak usage. It is possible students see the space as

full at 20% occupancy, rather than the 40-50% reported in other literature

(Applegate, 2009; İmamoğlu & Gürel, 2016; Khoo et al., 2016). For example,

once a study room has one person using the space it is considered full, even

though there may be 2-3 available chairs in the room. Similarly, as noted in

the sweeps and focus groups, a single student may use an entire four-person

table, making the space full with only one occupant. İmamoğlu and Gürel (2016)

write about territorial dividers as a way to maintain personal space, and

something focus group participants mentioned wanting were smaller, individual

work tables in place of the large four-person tables currently available. This

follows trends for communal study, or alone-together study, where students seek

silence lacking in other areas (e.g., dorm rooms, classrooms, residence hall

lounges, and others), but still want to be around others working on similar

tasks. It is clear from all three data points that quiet study space is highly

valued and sought after on campus, and the library, while providing some quiet,

still requires more to meet demand. This is consistent with recent literature

about growing demands for quiet spaces, and libraries should consider this

growing body of evidence as they plan for renovations.

Space-related services

While

not solely library-related, participants in all areas of research suggested the

library add café and stress-relief services. Café service was not surprising

given the percentage of people observed during sweeps with food or drink. As

the survey found, students frequently visit the library between classes and

throughout the day and Grab ‘n Go foods was rated highly as a need in the

survey (see Figure 2), having café access would benefit students. This leads

researchers to conclude current vending options are inadequate, including the

new single-serve coffee machine. Out of a specific request for nap pods within

the focus groups, student researchers included an option of “Stress relief room with nap pods/ massage

chairs/ stress relieving activities” for the survey question “I think the

library needs…” Surprising to librarian researchers, the request for stress

relief services came in second to “more quiet rooms.” Considering the other

spaces on campus in which students elect to study and complete work (e.g.,

cafés, residence hall lounges, and more), the desire for space-related

services, including Grab ‘n Go foods and stress relief rooms, is very

important.

Extended

hours and interlibrary loan are two other services frequently mentioned in both

the focus groups and survey. The request for extended hours has persisted for

years, and the library has adjusted hours to open earlier and close later on

weekends, including staying open until 2 A.M. during the last two weeks of the

semester. The study did not determine what extended hours would mean to users,

but existing headcount data does not support a need for extended hours. We

acknowledge this could be due to students knowing the library is closing, and

therefore moving to an alternate location long before closing. Unrelated to

library space, praise for interlibrary loan was common throughout all user

types in the focus groups. Researchers are unsure why this service connects to

library spaces for users, though it is possible students have picked up

physical interlibrary loan materials at the Checkout Desk, or focus group

questions about space-related library services evoked positive feelings toward

this service.

Limitations

The

researchers acknowledge this research had limitations. Multiple recorders’

interpretations during the seating sweeps may influence data. The librarians

conducting the research tried to mitigate this by training staff recorders with

a shared understanding of what to record.

Due

to low focus group participation, masters and doctoral students were not

surveyed. Similarly, a purposeful decision to exclude demographics was made to

shorten the survey. Therefore, researchers are unable to relate survey

responses back to specific demographic traits (e.g., commuter vs. residential,

class level), which may have proved valuable for understanding how different

student groups use library spaces.

Future Research

Future

space studies should investigate students’ need for quiet study spaces, and how

libraries may provide these spaces to their students. The need for quiet space

may signify a change from previous trends regarding redesigned library spaces.

In small academic libraries, would it better serve students to have more quiet

spaces than collaborative spaces, since the latter can be found other places on

campus? It is also worth exploring students’ use of undefined spaces, which may

be common in academic libraries.

Acknowledgements

The

authors would like to acknowledge others that were instrumental to the success

of this library space study: Faculty Advisers: Patricia Tweet, PhD and David

Baronov, PhD; Student Researchers: Mollie Flynn and Caroline Villa; and Library

staff members: Kate Ross, Marianne Simmons, Brian Lynch, Lynn Seavy, Stacy

Celata, and Britta Stackwick.

References

Andrews, C.,

Wright, S. E., & Raskin, H. (2015). Library learning spaces: Investigating

libraries and investing in student feedback. Journal of Library Administration, 56, 647-672. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01930826.2015.1105556

Applegate, R.

(2009). The library is for studying: Student preference for study space. The Journal of Academic Librarianship, 35, 341-346.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2009.04.004

Cha, S. H., & Kim, T. W. (2015). What matters for students’ use of

physical library space? The Journal of

Academic Librarianship, 41, 274-279. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2015.03.014

DeClercq, C. P.,

& Cranz, G. (2014). Moving beyond seating-centered learning environments:

Opportunities and challenges identified in a POE of a campus library. The Journal of Academic Librarianship, 40, 574-584.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2014.08.005

Ellison, W.

(2016). Designing the learning spaces of a university library. New Library World, 117, 294-307. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/NLW-01-2016-0006

Fallin, L.

(2016). Beyond books: The concept of the academic library as learning space. New Library World, 117, 308-320. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/NLW-10-2015-0079

Freeman, G. T.

(2005). The library as place: Changes in learning patterns, collections,

technology, and use. In Library as Place:

Rethinking Roles, Rethinking Space (pp. 1-10). Council on Library

Resources: Washington, DC.

Given, L. M.,

& Archibald, H. (2015). Visual traffic sweeps (VTS): A research method for

mapping user activities in the library space. Library & Information Science Research, 37, 100-108. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.lisr.2015.02.005

Given, L. M.,

& Leckie, G. L. (2003). “Sweeping” the library: Mapping the social activity

space of the public library. Library

& Information Science Research, 25, 365-385. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0740-8188(03)00049-5

Goodnight, C.,

& Jeitner, E. (2016). Sending out an SOS: Being mindful of students’ need

for quiet study spaces. In S. S. Hines & K. M. Crowe (Eds.), The Future of Library Spaces (Vol. 36,

pp. 103-129). Emerald Group Publishing Limited. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/S0732-067120160000036010

Hall, K., &

Kapa, D. (2015). Silent and independent: Student use of academic library study

space. Partnership: The Canadian Journal

of Library and Information Practice and Research, 10(1), 1-38.

Hanson, A.,

& Abresch, J. (2016). Socially constructing library as place and space. In

S. S. Hines & K. M. Crowe (Eds.), The

Future of Library Spaces (Vol. 36, pp. 103-129). Emerald Group Publishing

Limited. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/S0732-067120160000036004

İmamoğlu, Ç.,

& Gürel, M. Ö. (2016). “Good fences make good neighbors”: Territorial

dividers increase user satisfaction and efficiency in library study spaces. The Journal of Academic Librarianship, 42, 65-73.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2015.10.009

Khoo, M.,

Rozaklis, L., Hall, C., & Kusunoki, D. (2016). “A really nice spot”:

Evaluating place, space, and technology in academic libraries. College & Research Libraries, 77,

51-70. http://dx.doi.org/10.5860/crl.77.1.51

Khoo, M.,

Rozaklis, L., Hall, C., Kusunoki, D., & Rehrig, M. (2014). Heat map visualization of seating patterns

in an academic library. In iConference 2014 Proceedings (p. 612-620). http://dx.doi.org/10.9776/14274

Lux, V., Snyder, R. J., & Boff, C. (2016). Why users come

to the library: A case study of library and non-library units. The Journal of Academic Librarianship, 42, 109-117.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2016.01.004

Montgomery, S.

E. (2014). Library space assessment: User learning behaviors in the library. The Journal of Academic Librarianship, 40, 70-75.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2013.11.003

Montgomery, S.

E., & Miller, J. (2011). The third place: The library as collaborative and

community space in a time of fiscal restraints. College & Undergraduate Libraries, 18, 228-238. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10691316.2011.577683

Ojennus, P.,

& Watts, K. A. (2017). User preferences and library space at Whitworth

University Library. Journal of Library

and Information Sciences, 49, 320-334. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0961000615592947

Oldenburg, R.

(1997). Making college a great place to talk. In G. Keller (Ed.), The best of planning for higher education (pp.

90-94). Ann Arbor, MI: Society for College and University Planning.

Oliveira, S. M.

(2016). Space preference at James White Library: What students really want. The Journal of Academic Librarianship, 42, 355-367.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2016.05.009

Vaska, M., Chan,

R., & Powelson, S. (2009). Results of a user survey to determine needs for

a health sciences library renovation. New

Review of Academic Librarianship, 15, 219-234. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13612530903240635