Introduction

In 2009, Loyola Marymount University

opened its Doheny Information Commons as part of the

new William H. Hannon Library. The

Hannon Library is open 24/5 with free wireless and a liberal food and drink

policy. The first floor of the library features a café, the circulation desk,

lockers with electrical outlets, four walk-up computers, library classrooms,

reference stacks, and an information commons with 80 computers, 3 enclosed

presentation practice rooms, and an Information Desk for reference and basic

technology and printing help. Throughout the second and third floors are over

30 enclosed group study rooms that can be reserved online. The second floor

features a branded service desk for IT support, device repair, and equipment

checkout, a popular reading collection, print periodicals stacks, carrels for

both media and individual study, and book stacks. The third floor is the

designated quiet floor and features exhibit space, Archives and Special

Collections, individual study carrels and group tables, a faculty commons and

faculty technology sandbox, a large multi-purpose room, and book stacks.

The Doheny

Information Commons space met Bailey & Tierney’s (2008) traditional

definition of an information commons by featuring 80 computers as “single

workstation(s) with access to traditional

library services and productivity resources in a high-technology-rich

environment” (p. 2). Furthermore,

the library intended it to cater to the millennial student, who needs space

conducive to social learning, collaboration, and group activities (Lippincott,

2012). The same year the new space opened, Ross Housewright

(2009) warned that academic libraries were “at risk of losing their functional

relevance and fading to primarily symbolic importance” if they failed to adapt

to the changing information environment (p. 254). Additionally, Housewright asserted that it is important to align with the

changing needs of students and faculty by “redeploy(ing)

resources flexibly” (p. 259). The mission of the new commons was to support

academic life at LMU, but how long might it be until it was no longer offering

optimal support?

In

2013, the library strategic plan called for post-occupancy planning of emerging

space utilization needs in the public areas of the library. This reflects

Lippincott’s (2012) advice that “it

is important to collect information on the actual needs of students and not

just on needs perceived by librarians” (p. 540). The question for any

institution that has set up a new space as an information or learning commons

is aptly summed up by librarians from Harrisburg University of Science and

Technology: “We need to explore ways of assessing the extent to which learning

commons services and resources help students succeed as self-directed learners”

(Adams & Young, 2010, p. 159). We designed the study described in this article

to address the question of whether an information commons, after six years, was

still optimally supporting students’ academic life in a rapidly changing

environment.

Literature

Review

Published

research on the design and use of library spaces, especially for the purposes

of assessment and planning (or re-planning), has appeared regularly in the

second decade of the 21st century. This research has been framed

often in the context of paradigm changes that appear with each generation of

new libraries, as set out by the frequently cited university librarian emeritus

at Yale, Scott Bennett (2008, 2009). The most recent shift is identified as

“learning-centered,” with spaces in new and renovated libraries dedicated as

either learning or information commons, and Bennett (2009) calls on his

profession “to launch a design practice centered on learning” (p. 194). An

entire library might become a university’s information commons (Hisle, 2005), or through new additions or renovation

libraries could now contain “a flexible, reconfigurable space that is sized to

a reasonable subpopulation of students and equipped with group learning spaces

as appropriate” (Beagle, Tierney, & Bailey, 2006, p. 9). Neither the name

nor the space came to have a consistent definition or execution, but on the

whole this situation has not impeded the beneficial results for libraries or

librarianship (Bonnand & Donahue, 2010).

Even

as Beagle and others were contributing the vision and summing up the new

library spaces, their colleagues in the field had begun the research into

library spaces and users that would soon create a substantial body of research

with a broad spectrum of methodologies. These ranged from quantitative,

intensive seat counts (Dotson & Garris, 2008) to

the purely creative setting of the design charrette (Oliveira, 2016; Washburn

& Bibb, 2011). Some early studies used a quantitative approach with direct

observation sweeps (Applegate, 2009; Dotson & Garris,

2008; Given & Leckie, 2003) and simple paper

questionnaires (Gardner & Eng, 2005). These two

modes of quantitative data collection look at what users do, on the one hand,

and try to get at what users want and expect, on the other. This mixture of

direct observation combined with questionnaires created a key set of studies

(Holder & Lange, 2014; İmamoğlu & Gürel, 2016; May & Swabey,

2015; McCrary, 2017).

However,

the need to acquire data about both of these important aspects of library

spaces has, on the whole, led to research that uses two or more modes of

collection and often more than one methodological approach. Ethnographic

techniques have been popular, either as the sole approach (Bedwell

& Banks, 2013), or as part of a mixed method toolkit, such as a combination

of video observation, the NSSE, and user surveys (Webb, Schaller, & Hunley, 2008). Even larger mixes of methods have brought

together the quantitative survey, focus groups, filmed interviews, and

student-made films (Cowan, 2012), or time-lapse photography, unobtrusive

observation, and random-sampled surveys (Asher, 2017). However, “ethnography is

a complicated and time-consuming research method” (Khoo,

Rozaklis, & Hall, 2012, p. 82).

The

majority of research in this literature review looked at the use of space or

the behaviour of users in library spaces generally, with

a minority dedicated to pre-occupancy assessment for design (23%), or

post-occupancy assessment (18%). Further, not all of the latter had as their

subject a designated commons or similar space. Some research focused solely on

measures or ideal attributes of library or commons space. Cha & Kim (2015)

used surveys of academic library users in the Netherlands, while the TEALS

standard was the product of another (Abbasi, Elkadi, Horn, & Owen, 2012). Only two longitudinal

studies exist (Fox & Doshi, 2017; Montgomery,

2014). We believe that our research makes a strong contribution to this

important post-occupancy category of library space assessments and data.

Another

gap that we identified is that of studies that provide detailed data on use of

the computers and devices that are the key components of the information

commons model. Even though the quantitative approach predominates in the

research under review (about 42%, with an additional 37% if mixed-method

research is added), and direct observation is frequently employed, only two

studies (5%) included observation of the screen itself: that is, what the users

were actually doing on their computers and devices while they were in the

library. To answer the question of what students “really do” in the library, Paretta & Catelano (2013)

used direct observation at two sites. These researchers did not look at space

use or other factors, but do provide highly detailed data on print vs.

computer, and academic activity vs. leisure activity. The one other study also

utilized direct observation, and set out to analyze the use of a particular

library space (not a commons), but didn’t provide any detail about the

frequency of academic vs. leisure use of technology (Faletar

Tanackovic, Lacović, & Gašo, 2014).

Is

there a developing evidence base of common findings among space studies? The

preponderance of users working on their own has been frequently found (Bryant,

Matthews, & Walton, 2009; Crook & Mitchell, 2012; Ferria

et al., 2017; Holder & Lange, 2014; Thomas, Van Horne, Jacobson, &

Anson, 2015). One ethnographic study highlighted single users “appropriating”

group tables by spreading out personal items (Bedwell

& Banks, 2013, p. 12). On the other hand, if group space is not provided,

it will be improvised (Hursh & Avenarius, 2013; Webb, Shaller,

& Hunley, 2008).

The

research is not clear about other elements of expectations for library spaces,

however. Students still value and prefer a quiet library, despite predictions

about upcoming generations, but what constitutes excess or distracting noise

appears to be contextual (Cowan, 2012; Crook & Mitchell, 2012; Faletar Tanackovic, Lacović, & Gašo, 2014; Khoo, Rozaklis, Hall, & Kusunoki,

2017; McCaffrey & Breen, 2016; Newcomer, Lindahl,

& Harriman, 2016; Regalado & Smale, 2015;

Suarez, 2007). Even very recent studies suggest that “students consider the

quiet communal spaces integral to their experience of the library” (Yoo-Lee, Lee, & Velez, 2013, p. 509).

Furniture

is another component of the information commons that some writers thought would

need to depart from traditional library practices (Hisle,

2005). This may not entirely be the case. More than a few studies indicate that

the ideal workspace may be “a big desk,” that is, rectangular, no-frills

tables, or the old-fashioned carrel (Hall & Kapa 2017). Arguably, “space in

which to spread themselves and their belongings out” (Washburn & Bibb,

2011) is the feature in question, rather than the furniture itself. Not all the

data agrees. Ferria et al. (2017) found booths popular,

and Webb, Schaller, & Hunley (2008) found 60% of

respondents split between wanting tables and a preference for soft seating.

Aims

In 2009, this new library had opened

with a “perfect” Information Commons space designed to support the millennial student.

After six years, our aim was to see if students were utilizing the Information

Commons in unexpected ways and deviating from the anticipated “millennial”

behavior for which we had built it. We designed our post-occupancy study to

answer the following research questions:

·

What areas of the Information

Commons do students really use or not use?

·

What furniture configurations are

preferred?

·

What mix of technology, resources,

and activities are students engaged with inside of the space?

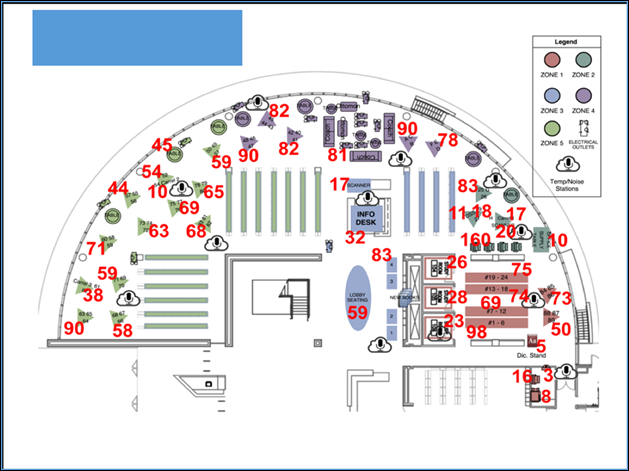

Figure 1

Observation zones of the Information Commons.

We found that 67 respondents (27%) in the survey said

they were eating or drinking, which we directly observed 695 times (33%). The

users’ concerns with eating and drinking while at work appeared in survey and

whiteboard poll responses, where 24 comments suggested improvements such as

snack vending machines, a water bottle refilling station, or a designated food

zone. There were eight users who said that there should be less trash and food.

Respondents

self-reported utilizing a library computer 169 times (68%) for email and 149

times (60%) for myLMUConnect, while only 119 people

(48%) reported using a library computer for productivity software and 102

people (41%) for library resources (see Figure 4). The only significant usage

captured through direct observation was productivity software, observed 885

times (42%). Users reported frequently multi-tasking with additional devices

while they used the library computers, including smart phones 126 times (51%),

headphones 99 times (40%), and laptops 94 times (38%) (See Figure 5). Direct

observation noted these devices, although less frequently. Both methods found

tablets very little used.

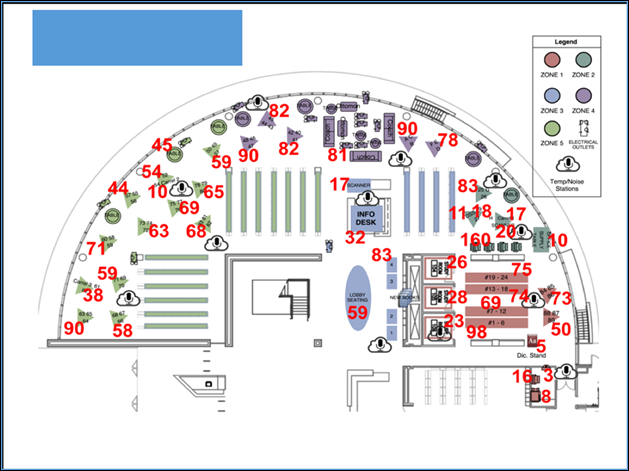

Figure 6

Average temperature and average noise level.

Environment

The

average temperature was between 72 and 75 degrees Fahrenheit (see Figure 6)

across all 5 zones, but there was variation. In zone 5, it got as low as 67

degrees, and in zone 2 as low as 67.5 degrees. There were nine respondents who

commented either in the patron survey or the whiteboard polls that the

temperature was too cold (see Appendix G). The average decibel level was

between 50 and 55, but there was also wide variation. In zone 3, observers

recorded up to 76.8 dBA. Zones two and three were the

noisiest because of their proximity to the printers and the lobby and

Information Desk. There were 32 students who commented that it was too loud and

that there should be a designated “no talking” and “no cell phones” area.

Remarkably, there were 161 reports of unattended belongings also observed, most

frequently after 9 p.m. We also observed several broken power outlets,

prompting users to plug into more distant outlets to compensate, creating a

trip hazard. Of the observations in zone

5, broken lights were observed 16 (13%) times, and 4 students commented it

needed to be brighter.

Discussion and Outcomes

Although the

planners and architects designed the Information Commons as a collaborative,

social learning space, the results of the study indicate that students want

quiet, privacy, and space to spread out, along with cleanliness. Since we only

observed 1412 (67%) students actually using a library computer (often they were

using their own devices while sitting at a computer workstation), we determined

that they could benefit from study space not tied to a desktop computer. We

opened up more study space in the Information Commons in the summer of 2016 by

emptying underutilized reference stacks and replacing them with over 30

additional seats (large rectangular tables and chairs). In the summer of 2017,

we installed floor-box power outlets to go along with this new seating.

We also made

a handful of small improvements based on the study, including the installation

of self-serve dispensers with wipes for cleaning keyboards and tabletops. We

worked with IT and Facilities to set up an inventory for outlets, Ethernet

ports, and light fixtures that could be checked regularly. Responding to

comments in our surveys, we made sure to supply new iMac mice, installed a new

water bottle filling station, and relocated one printer to the far side of the

Information Commons. Another upcoming change will be to install bag hooks

underneath the computer workstations that are close together to offer more

space.

Even

though our study established that a majority of our users preferred library

computer workstations with privacy and space to spread out, we still had a gap

in knowledge about other furniture preferences. As Bieraugel

& Neill (2017) point out in an article applying Bloom’s taxonomy to library

spaces and creativity, it is important to design learning spaces for different

intended behaviors (p. 37). They determined, for example, that quiet study

space and computer labs support reflection, but on the other hand communal

tables support networking (p.48).

There were 28 respondents who suggested napping pods, newer

furniture, more desk space, and more comfort during our study. We therefore

undertook a furniture survey done in spring 2017 to gather more information.

This follow-up research revealed that for tables and chairs without a library

computer, 103 respondents (54%) preferred 4 chairs facing each other because

this was conducive to studying or homework, collaboration, and offered space

for their belongings (see Table 1). A great majority, 148 (78%), preferred a

rectangular table shape. Therefore, we rearranged the new seating into

rectangular tables with four chairs facing each other.

The furniture survey asked about

preferences for doing additional specific activities. For working alone, 99

students (52%) preferred the S-Divider, while 74 (39%) preferred a carrel. Beyond

the obvious factor of privacy, those choosing the S-Divider mentioned comfort

and aesthetics as important factors, while those choosing a carrel mentioned a

good writing surface. When asked about their preference for collaborating, 89

(47%) chose an enclosed booth for privacy and its seating configuration, while

72 (38%) chose a high-back booth for its seating configuration and comfort.

This seating configuration is consistent with the preference for the table and

chair configuration as four chairs facing each other. For lounge furniture, 87

respondents (46%) preferred a high-back couch with coffee table, while 70 (37%)

preferred an armchair and coffee table. Comfort was an important factor behind

both choices, while those opting for the high-back couch also mentioned

aesthetics. We were able to put this recommendation to use in the spring of

2017 when we replaced the low-back couches in the first floor lobby area with

armchairs and coffee tables. We plan to make future strategic budget requests

for furniture based on these preferences.

To address

the general noise problem in the Information Commons, we consulted with Newson

Brown Acoustics, LLC. They suggested an electrical sound masking system to make

background noise or white noise. Other suggestions included sound baffles,

adding physical barriers between workstations, or designating certain areas for

quiet vs. social and putting up signage. Also, our follow-up furniture survey

found that 86 respondents (45%) preferred to take a phone call in a soundproof

phone booth because it offered privacy and quiet. These are similar to possible

solutions found in the literature: McCaffrey and Breen (2016) found evidence

that “interventions such as the development of a noise policy, zoning,

rearranging of furniture, removal of service points from reader spaces, and

structural improvements to reduce noise travel are worthwhile interventions for

libraries to consider when faced with noise problems” (p. 788).

Limitations

The direct

observation methodology had limitations. If users had multiple browsers open

during the direct observations, we only recorded what was in the open window on

their screen at that moment in time. It was also difficult to be discreet when

observing users; we recorded “can’t tell” for what purpose they were using a

library computer on 527 (25%) of the direct observations. Some students failed

to take the whiteboard polling methodology seriously and left facetious

answers. Another limitation was the lack of real measurement of users’ true

level of collaboration during a seating sweep since it provides only a snapshot

in time rather than an ethnography. A limitation to the follow-up furniture

survey came with it being online only, and therefore we recruited only those

using a computer or device. The final limitation was that all observation and

survey instruments were limited to the Information Commons space. We therefore

have data only from those who we found in that space, but no data from those

who, from choice or other circumstance, were not in that space. We don’t know

who chose not to be there, or who wanted to be there but couldn’t, and the

insights those groups of users might have provided.

Conclusions

This mixed

methods case study explored the usage, satisfaction, and preferences of users in the Hannon

Library Information Commons. Independent study

dominated the space usage. Students valued spaciousness, quiet, privacy, and a

clean environment. Students frequently multi-tasked with additional devices as

they simultaneously used a library computer, including cell phones, headphones,

and laptops. Also, unattended belongings were frequently observed along with

broken electrical outlets. The study paved the way for improvements and the

partial redesigning of the space. Even though our study confirmed some findings

from other studies, including a preference for working alone and the desire for

quiet, it is important for each library to conduct its own assessment because “one size does

not fit all academic libraries” and “designs will, and should be, different on

every campus” (Head, 2016, p. 26).

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to acknowledge contributions by the following

colleagues: LMU Library Reference & Instruction Department (Elisa Slater

Acosta, Jennifer Masunaga, Desirae Zingarelli-Sweet, Lindsey McLean, Nataly Blas, Kathryn Ryan,

Aisha Conner-Gaten), Burney Wong, Denise Blanchet,

Katherine Donaldson, Rachel Deras, Angie So, Javier

Garibay, 2015 LMU Library Assessment Committee, LMU Library Information Commons

student workers, LMU LAC Group overnight staff, and Laura Massa.

References

Abbasi, N., Elkadi, H.,

Horn, A., & Owen, S. (2012, October). TEALS (Tool for Evaluation of

Academic Library Spaces) project :

Evaluating physical library spaces. Presented at the Library Assessment

Conference: Building effective, sustainable, practical assessment,

Charlottesville, VA. Retrieved from http://dro.deakin.edu.au/view/DU:30048261

Adams, N. E., & Young, J. B. (2010). Users

learning from users: Building a learning commons from the ground up at a new

university. College & Undergraduate Libraries, 17(2–3),

149–159. https://doi.org/10.1080/10691316.2010.481607

Applegate, R. (2009). The library is for studying:

Student preferences for study space. Journal of Academic Librarianship, 35(4),

341–346. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2009.04.004

Asher, A. D. (2017). Space use in the commons:

Evaluating a flexible library environment. Evidence Based Library &

Information Practice, 12(2), 68–89. https://doi.org/10.18438/B8M659

Bailey, D. R., & Tierney, B. G. (2008). Transforming

library service through information commons: case studies for the digital age.

Chicago: American Library Association.

Beagle, D. R., Tierney, B. G., & Bailey, D. R.

(2006). The information commons handbook. New York: Neal-Schuman

Publishers.

Bedwell, L., & Banks, C. (2013). Seeing through the eyes of students: Participant

observation in an academic library. Partnership: The Canadian Journal of

Library & Information Practice & Research, 8(1), 1-17. https://doi.org/10.21083/partnership.v8i1.2502

Bennett, S. (2008). The information or the learning

commons: which will we have? Journal of Academic Librarianship, 34(3),

183–185. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2008.03.001

Bennett, S. (2009). Libraries and learning: a history

of paradigm change. portal: Libraries and

the Academy, 9(2), 181–197. https://doi.org/10.1353/pla.0.0049

Bieraugel, M., & Neil, S. (2017). Ascending Bloom’s

Pyramid: Fostering student creativity and innovation in academic library

spaces. College & Research Libraries, 78(1), 35-52. https://doi.org/10.5860/crl.78.1.35

Bonnand, S., & Donahue, T. (2010). What’s in a name? The

evolving library commons concept. College & Undergraduate Libraries,

17(2–3), 225–233. https://doi.org/10.1080/10691316.2010.487443

Bryant, J., Matthews, G., & Walton, G. (2009).

Academic libraries and social and learning space: A case study of Loughborough

University Library, UK. Journal of Librarianship and Information Science,

41(1), 7–18. https://doi.org/10.1177/0961000608099895

Cha, S. H., & Kim, T. W. (2015). What matters for students’ use of physical library

space? Journal of Academic Librarianship, 41(3), 274–279. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2015.03.014

Cowan, S. M. (2012). Assessment 360: Mapping

undergraduates and the library at the University of Connecticut. Storrs,

CT: University of Connecticut Libraries. Retrieved from https://www.clir.org/pubs/resources/Assessment360.pdf

Crook, C., & Mitchell, G. (2012). Ambience in

social learning: student engagement with new designs for learning spaces. Cambridge

Journal of Education, 42(2), 121-139. https://doi.org/10.1080/0305764X.2012.676627

Dotson, D. S., & Garris,

J. B. (2008). Counting more than the gate: Developing

building use statistics to create better facilities for today’s academic

library users. Library Philosophy & Practice, Sep2008, 1–13.

Faletar Tanackovic, S., Lacović, D., & Gašo, G.

(2014). Student use of library physical spaces: Unobtrusive observation of

study spaces in an academic library. Libraries

in the Digital Age (LIDA) Proceedings, 13. Retrieved from http://ozk.unizd.hr/proceedings/index.php/lida/article/view/114/116

Ferria, A., Gallagher, B. T., Izenstark,

A., Larsen, P., LeMeur, K., McCarthy, C. A., & Mongeau, D. (2017). What are they doing anyway?: Library as place and student use of a university library.

Evidence Based Library and Information Practice, 12(1), 18–33. http://dx.doi.org/10.18438/B83D0T

Fox, R., & Doshi, A.

(2017). Longitudinal assessment of “user-driven” library commons spaces. Evidence

Based Library and Information Practice, 8(2), 85–95. http://dx.doi.org/10.18438/B8761C

Gardner, S., & Eng, S.

(2005). What students want: Generation Y and the changing function of the

academic library. portal: Libraries and the

Academy, 5(3), 405–420. https://doi.org/10.1353/pla.2005.0034

Given, L.

M., & Archibald, H. (2015). Visual traffic sweeps (VTS): A research method

for mapping user activities in the library space. Library and Information

Science Research, 37(2), 100-110. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.lisr.2015.02.005

Given, L. M., & Leckie,

G. J. (2003). “Sweeping” the library: Mapping the social activity space of the

public library. Library and Information Science Research, 25(4),

365–385. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0740-8188(03)00049-5

Hall, K., & Kapa, D. (2017). Silent and

independent: Student use of academic library study space. Partnership: The

Canadian Journal of Library and Information Practice and Research, 10(1),

1-38. https://doi.org/10.21083/partnership.v10i1.3338

Halling, T. D., & Carrigan, E.

(2012). Navigating user feedback channels to chart an evidence based course for

library redesign. Evidence Based Library and Information Practice, 7(1),

70–81. https://doi.org/10.18438/B81W35

Head, A. J. (2016). Planning and designing academic

library learning spaces: Expert perspectives of architects, librarians, and

library consultants. Seattle, Washington: The University of Washington

Information School.

Hewson, C.

(2006). Mixed Methods Research. In V. Jupp (Ed.), The

SAGE dictionary of social research methods London: Sage. http://doi.org/10.4135/9780857020116

Hisle, W. L. (2005). The changing role of the library in the academic

enterprise. Presented at the 12th ACRL National Conference.

Minneapolis, MN. Retrieved from http://www.ala.org/acrl/sites/ala.org.acrl/files/content/conferences/pdf/hisle05.pdf

Holder, S., & Lange, J. (2014). Looking and

listening: A mixed-methods study of space use and user satisfaction. Evidence

Based Library & Information Practice, 9(3), 4-27. https://doi.org/10.18438/B8303T

Housewright, R. (2009). Themes of change in corporate libraries:

Considerations for academic libraries. portal:

Libraries and the Academy, 9(2), 253–271. https://doi.org/10.1353/pla.0.0048

Hursh, D. W., & Avenarius, C. B. (2013). What

do patrons really do in music libraries? An ethnographic approach to improving

library services. Music Reference Services Quarterly, 16(2),

84-108. https://doi.org/10.1080/10588167.2013.787522

İmamoğlu, Ç., & Gürel, M. Ö. (2016). “Good fences make good neighbors”:

Territorial dividers increase user satisfaction and efficiency in library study

spaces. The Journal of Academic Librarianship, 42(1), 65–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2015.10.009

Khoo, M., Rozaklis, L., & Hall, C. (2012). A survey of the use of ethnographic methods in the

study of libraries and library users. Library & Information Science

Research, 34(2), 82–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lisr.2011.07.010

Khoo, M., Rozaklis, L., Hall, C., & Kusunoki,

D. (2017). “A really nice spot”: evaluating place, space, and technology in

academic libraries. College & Research Libraries, 77(1),

51-70. https://doi.org/10.5860/crl.77.1.51

Kitchenham, A. D. (2010). Mixed methods in

case study research. In A. J. Mills, G. Durepos, & E. Wiebe (Eds.), Encyclopedia of case

study research. Los Angeles, Calif.: Sage.

Lippincott, J. K. (2012). Information commons: Meeting

millennials’ needs. Journal of Library Administration, 50(1),

27–37. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01930826.2012.707950

May, F., & Swabey, A.

(2015). Using and experiencing the academic library: A multisite observational

study of space and place. College & Research Libraries, 76(6),

771-795. https://doi.org/10.5860/crl.76.6.771

McCaffrey, C., & Breen, M. (2016). Quiet in the

library: An evidence-based approach to improving the student experience. portal: Libraries and the Academy, 16(4),

775–791. https://doi.org/10.1353/pla.2016.0052

McCrary, Q. D. (2017). Small library research: Using

qualitative and user-oriented research to transform a traditional library into

an information commons. Evidence Based Library and Information Practice,

12(1), 34–49. http://dx.doi.org/10.18438/B8863F

Montgomery, S. E. (2014). Library space assessment:

User learning behaviors in the library. Journal of Academic Librarianship,

40(1), 70–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2013.11.003

Newcomer, N. L., Lindahl, D., & Harriman, S. A.

(2016). Picture the music: Performing arts library

planning with photo elicitation. Music Reference Services Quarterly, 19(1),

18. https://doi.org/10.1080/10588167.2015.1130575

Oliveira, S. M. (2016). Space preference at James

White Library: What students really want. Journal

of Academic Librarianship 42(4), 355–367. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2016.05.009

Paretta, L. T., & Catalano, A. (2013). What students really do in the library: An

observational study. Reference Librarian, 54(2),

157-167. https://doi.org/10.1080/02763877.2013.755033

Regalado, M., & Smale,

M. A. (2015). “I am more productive in the library because it’s quiet”:

Commuter students in the college library. College & Research Libraries,

76(7), 899. https://doi.org/10.5860/crl.76.7.899

Simons, H.

(2009). Case study research in practice. Los Angeles:

Sage.

Suarez,

D. (2007). What students do when they study in the

library: Using ethnographic methods to observe student behavior. Electronic

Journal of Academic & Special Librarianship, 8(3).

Thomas, B., Van Horne, S., Jacobson, W.,

& Anson, M. (2015). The design

and assessment of the Learning Commons at the University of Iowa. The

Journal of Academic Librarianship, 41(6), 804–813. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2015.09.005

Washburn, A., & Bibb, S. C. (2011). Students

studying students: An assessment of using undergraduate student researchers in

an ethnographic study of library use. Library & Information Research,

35(109), 55–66.

Webb, K. M., Schaller, M. A., & Hunley, S. A. (2008).

Measuring library space use and

preferences: Charting a path toward increased engagement. portal:

Libraries and the Academy, 8(4), 407-422. http://doi.org/10.1353/pla.0.0014

Yoo-Lee, E., Lee, T. H., & Velez,

L. (2013). Planning library spaces and services for

Millennials: an evidence-based approach. Library Management, 34(6),

498-511. https://doi.org/10.1108/LM-08-2012-0049

Appendix A

Direct Observation Form

Individual Patron

Activity Drop Down Menus

What day of the

week is your shift?

o Monday

o Tuesday

o Wednesday

o Thursday

o Friday

o Saturday

o Sunday

What time of the

day is your shift?

o Morning (9a-noon)

o Afternoon (1-4p)

o Evening (5-8pm)

o Late Night (after

9pm)

You are going to

mark/record the activities of each person in your zone. Fill out one form for

each person. First, select your Zone. Then select the approximate area in the

zone for the location of the person you wish to record.

Are there

unattended belongings in the space (belongings, but no person present)?

o Yes

o No

What is the gender

of the person?

o Male

o Female

o Unknown

o N/A- group

presentation room

o Unattended

belongings present

For observations in

the Group Presentation rooms, complete one observation survey per room, NOT PER

PERSON. Which group presentation room technology is being used in the room?

Check all that apply.

o LCD

o Wall Talker

o Camera

o Laptop Attached to

Camera

Group Presentation

Room - Record the total number of People in the room:

______ # Females

______ # Males

What is the person

doing at the copier?

o Scanning

o Copying

o Printing

o Faxing

o None of the Above

or Can't Tell

Is office equipment

(hole punch, stapler, or paper cutter) being used?

o Yes

o No

Is DSS software

such as Jaws, Kurtzweil, or ZoomText being used?

o Yes

o No

Is the person using

the scanner?

o Yes

o No

Is the person using

the DSS magnifier?

o Yes

o No

What is the person

doing at printer(s)?

o Releasing a Print Job

o Waiting for a Print

Job

o Having Trouble with

a Print Job

o None of the Above

How long did the

person use the walk-up computer?

o Less than 1 Minute

o 1 -5 Minutes

o 5 -10 Minutes

o > 10 Minutes

Record the person's

level of collaboration with other people.

o No collaboration-

working alone

o Social interaction

(appears not related to schoolwork)

o Paired (working

with another person on schoolwork)

o Group (working with

2 or more others on schoolwork)

What percentage of

the available space is the person or group using?

______ % of space

What is the seating

arrangement of the pair?

o Beside each other

o Across from each

other

o Diagonal

o Other

____________________

Note the

subject('s) technology use, if any. Which of these devices are in use? Check

all that apply

o Library Computer

o Laptop

o Smart phone

o Headphones

o E-reader

o Tablet or Notebook

o None

o Other-specify

____________________

What was the

purpose of using this Library owned computer? If possible, please specify.

o Library Resource

(Catalog, Database, E-book) ____________________

o Recreational

(Games, non-school related, social media) ____________________

o Email

o Productivity

Software (Microsoft Office) ____________________

o Specialized

Software (such as Matlab, SPSS, Photoshop) ____________________

o myLMUConnect ____________________

o Other/Can't Tell

____________________

Record all the

Activities that you observe for this subject(s).

o Browsing for/using

Lib Book

o Eating or Drinking

o Interacting w/

Staff Member

o Printing

o Reading, Writing,

or Studying (Non Computer)

o Sitting on Floor /

Squatting

o Sitting on Library

Furniture

o Sleeping

o Standing

o Talking

o Using Earplugs

o Using Electrical

Outlet

o Using Ethernet

cable

o Waiting in Line

o Walking (in

transit)

o Other

____________________

Note any additional

observations about the person's activities/belongings/seating or the space

itself (e.g. use of extension cable, wearing a coat, frustration, confusion)

Appendix B

Environment Survey

What day of the

week is your shift?

o Monday

o Tuesday

o Wednesday

o Thursday

o Friday

o Saturday

o Sunday

What time of the

day is your shift?

o Morning (9a-noon)

o Afternoon (1-4pm)

o Evening (5-8pm)

o Late Night (after

9pm)

You will begin your

shift by recording details about the general environment of your zone. First,

select Your Zone.

o 1

o 2

o 3

o 4

o 5

Select the approximate

area in zone 1 for the location of where you are standing.

o Doorway of Copy

Machine Room

o GP 106

o In Between

Computers #89/ & #7

Select the

approximate area in zone 2 for the location of where you are standing.

o In Front of

Leonardo Printer

o Between Computer G

& Table

Select the

approximate area in zone 3 for the location of where you are standing.

o In front of Walk-Up

Computer #1

o Information Commons

Desk

Select the

approximate area in zone 4 for the location of where you are standing.

o Between Table &

Computer 45

o Between Couches

& Computer A

Select the

approximate area in zone 5 for the location of where you are standing.

o Between Computer 77

& Computer 80

o Between Computer 82

& Reference Stacks PN 1997-PQ 6010

o In Front of

Computer 67

Record the Temperature

Level in your Area (in degrees F).

______ degrees F

Record the Humidity

Range in your Area (%).

______ %

Record the Noise

Level in your Zone.

______ dBA

Is there any

"Out of Order" Equipment in your Zone?

o None

o Computers

o Printers

o Scanners

o Lights

o Photocopier

Is there any

Equipment or Furniture in your zone that is Messy or Unclean (e.g. spills,

excessive trash)?

o Yes

o No

Please describe

what was messy or unclean

Appendix C

Patron Survey

Please take a few minutes to fill out this brief

survey so we can improve the Information Commons space!

By completing this survey, you will have the

chance to enter a raffle drawing to win a $50 Amazon gift card (provided you

give us your email address).

Below is a consent form allowing us permission

to use your anonymous feedback. No information that

identifies you will be collected or released.

What activities are

you engaging in today on the Library's first floor? Select all that apply.

o Print

o Study

o Read

o Eat/Drink

o Write

o Get Help from a

Staff Member

o Photocopy

o Group Work

o Take a Nap

o Talk/Socialize

o Scan (scanner)

o Use a Reference

Book

o Other- please

specify ____________________

Which devices are

you using within the Library's first floor space today? Select all that apply.

Include both devices supplied by the Library and devices you bring with you.

o Library Computer

o Laptop

o Smart Phone

o Headphones

o E-Reader

o Tablet or Notebook

o None

o Other- please

specify ____________________

For what purpose(s)

are you using the Library Computers today? Select all that apply.

o Library Resources

(library catalog, research databases, e-books)

o Recreational

(games, social media)

o Email

o Productivity

Software (Microsoft Office)

o Specialized

Software (used in my Schoo/College, such as Matlab) ____________________

o myLMUConnect

o Other- please

specify ____________________

When you picked

your spot on the first floor of the Library today, which factors were most

important to you? Please choose the top FIVE factors from the list on the left

and drag & drop them into the “Top Five Factors” Box on the right in order

of importance (#1 = most important).

|

Top Five Factors

|

|

______ Spacious

(can spread out)

|

|

______ Quiet

|

|

______ Ambient or

Background Noise

|

|

______ Nice View

|

|

______ Privacy

|

|

______ Proximity

to Other Students

|

|

______ Bright

Lighting

|

|

______

Comfortable Seating

|

|

______ Access to

Power Outlets

|

|

______

Comfortable Temperature

|

|

______ Access to

a Library Computer

|

|

______ Aesthetics

(decor)

|

|

______ Talking is

Tolerated

|

|

______

Cleanliness

|

Describe your level

of collaboration with other people today on the first floor of the Library.

o No collaboration- I

am working alone

o Paired (working

with another person)

o Working with a

group of 2 or more

o Other- please

specify ____________________

What could be done

to make the “Information Commons” (first floor of the Library) a better space

for you?

What is your

gender?

o Male

o Female

What is your status

at LMU?

o Undergraduate

student

o Graduate student

o Faculty/staff

o Guest or Other

Is there anything

you would like to add?

Appendix D

Furniture Survey (images available at https://lmu.box.com/v/furniturestudy)

These questions only pertain to

the "Information Commons" space located on the First Floor of the

Hannon Library. This is the area you are currently sitting in. The space

includes over 80 iMac computers, printers, and the Information Desk. We need

your feedback so we can improve the space. Thanks for your input!

Pick Your Preferred

Spot to Use a Library Computer

o

Private

o

Open

Which option(s)

best explains why you chose this spot to use a library computer?

o

Privacy

o

Space for My Stuff

o

Noise Level

o

Open Space / Not Closed Off

o

Location (e.g. close to printer)

o

Collaboration

Pick Your Favorite

Table and Chair Configuration

o

4 Chairs Facing Each Other

o

1 Chair Against the Wall

o

1 Row Facing the Same Direction

o

2 Chairs Facing Each Other

o

2 Chairs Against the Wall

Which option(s)

best explains why you chose this table and chair configuration?

Conducive to Studying / Homework

o

Space for my Stuff

o

Collaboration

o

Open Space / Not Closed Off

o

Privacy

o

Quiet

Do you Prefer a

Rectangular or Round Table?

o Rectangular Table

o Round Table

Which option(s)

best explains why you chose this table?

o

Space for My Stuff

o

Comfort (e.g. easier on my legs)

o

Conducive to Studying / Homework

o

Collaboration

Pick Your Ideal

Private Space for Working Solo

o

S-Divider

o

Carrel

o

Space Pod

Which option(s)

best explains why you chose this spot as your ideal private space for working

alone?

o

Privacy / More Closed Off

o

Comfort

o

Writing Surface (e.g. table)

o

Aesthetics / Appearance

o

Compact (efficient use of space)

o

Space for My Stuff

o

Noise Level

o

Open Space / Less Closed Off

Pick Your Ideal

Private Space for Collaborating

Enclosed Booth

o

High-Back Booth

o

High- Back Couch

Which option(s)

best explains why you chose this spot as your ideal space for collaborating?

Seating Configuration (e.g. beside, across)

o

Comfort

o

Privacy / More Closed Off

o

Writing Surface (e.g. table)

o

Space for My Stuff

o

Noise Level

o

Open Space / Less Closed Off

Choose your

Favorite Lounge Furniture

o

High Back Couch with Coffee Table

o

Armchair and Coffee Table

o

Reverse-C Chair

o

Low Back Couch with Coffee Table

o

Barstool and Counter

Which option(s)

best explains why you chose this furniture for a lounge area?

Comfort

o

Aesthetics / Appearance

o

Conducive to Work / Study

o

Collaboration or Socializing

o

Seating Configuration (e.g. beside, across)

o

Space for My Stuff

o

Writing Surface (e.g. table)

o

Privacy

Where would you

prefer to take a phone call in the Information Commons?

Soundproof Phone Booth

o

Move to Another Area in the Library

o

Group Study Room

o

Computer Carrel

o

Open Study Area

Which option(s)

best explains why you chose this spot to take a phone call?

o

Privacy

o

Quiet

o

Open Space / Not Closed Off

o

Space for my Stuff

Appendix E

Heat Map of People

Observed in Each Area

Appendix F

Tableau Visualization of Activity in Each Zone

Appendix G

Top Comments from Patron Survey and Whiteboard Polls

|

Category

|

# Times

|

Details

|

|

Noise/Too Loud

|

32

|

Designate a “no talking” and “no cell phones” area

|

|

Furniture

|

28

|

Napping pods (9), newer

furniture, more desk space, more comfort

|

|

Library Desktop Computer Station

|

25

|

More computers, kick out people not using the computer,

cleaner, more specialized software (7), mice that work better (6)

|

|

Food & Drink

|

24

|

Snacks/vending machines, water

bottle refilling station, designated food zone

|

|

Miscellaneous Space Suggestions

|

15

|

Charging station, plants, 3D

printer, etc.

|

|

Temperature/Too Cold

|

9

|

Too cold

|

|

General Cleanliness

|

8

|

Less food and trash

|

|

Printers

|

7

|

Spread out to more locations,

improve functionality, pay without OneCard

|

|

Hours

|

5

|

Open 24/7

|

|

Lighting

|

4

|

Brighter

|

![]() 2017 Archambault and Justice. This is an Open Access article distributed under

the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the same

or similar license to this one.

2017 Archambault and Justice. This is an Open Access article distributed under

the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the same

or similar license to this one.