Commentary

Gathering Evidence for Routine Decision-making

Alison

Brettle

Professor of

Health Information and Evidence Based Practice

School of

Health and Society

University of

Salford

Salford,

Manchester, United Kingdom

Email: a.brettle@salford.ac.uk

Received: 17 Nov.

2017 Accepted:

23 Nov. 2017

![]() 2017 Brettle. This is an Open Access article distributed

under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike

License 4.0 International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use,

distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is

properly attributed, not used for commercial purposes, and, if transformed, the

resulting work is redistributed under the same or similar license to this one.

2017 Brettle. This is an Open Access article distributed

under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike

License 4.0 International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use,

distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is

properly attributed, not used for commercial purposes, and, if transformed, the

resulting work is redistributed under the same or similar license to this one.

This paper is

based on the opening keynote address at the 9th International

Evidence Based Library and Information Practice Conference, Philadelphia, 18-21

June 2017.

Introduction

Discussions about

evidence based library and information practice (EBLIP) often focus on the use

of research evidence in decision making. However, EBLIP can be an approach to

professional practice that is about being

evidence based, rather than just a one-off event or a restriction to

decision-making alone. This involves:

·

Questioning our practice

·

Gathering or creating the evidence through research

and evaluation

·

Using information or evidence wisely to: make

decisions about our practice; improve our practice; make decisions about our

services; help others make decisions about our services (by demonstrating our

effectiveness, impact, value, or worth); and using our professional skills to

help others make their own evidence-based decisions (Koufogiannakis &

Brettle, 2016).

Using examples

from the United Kingdom (UK), this paper examines the wider range of evidence

that librarians can gather or create to make decisions about their practice and

services. These examples also demonstrate how librarians can use this evidence

in terms of advocacy, to help others make decisions about their services. In

this paper EBLIP is considered holistically; research evidence, local evidence,

and professional knowledge are all taken

into account (Koufogiannakis, 2011). A wide range of different types of

evidence may also be used (Table 1).

Table 1

Different Types of

Research Evidencea

|

Research |

Local |

Professional |

|

Quantitative |

Statistics |

Professional expertise |

|

Qualitative |

Assessment/evaluation |

Tacit knowledge |

|

Mixed |

Documents |

Input from colleagues |

|

Secondary |

Librarian observation |

What other libraries do |

|

User feedback |

Non-research literature |

|

|

Anecdotal evidence |

||

|

Organizational realities |

aAdapted from

(Koufogiannakis & Brettle, 2016).

Gathering Research

Evidence

The Chartered

Institute of Library and Information Professionals (CILIP) is keen to support

its members in advocacy. High quality research evidence of the value of library

and information professionals is therefore needed. To this end CILIP commissioned a systematic

scoping review of evidence that collated evidence on the value and impact of

professionally trained library, information and knowledge workers (Brettle

& Maden, 2016). This evidence is summarised below and can be used by the

professional body to advocate on behalf of its members, and by library and

information professionals themselves to demonstrate value to their

stakeholders.

When trying to

demonstrate impact or value, outcomes or outcome measures are often used.

Outcomes are “the consequences of deploying services on the people who encounter

them or the communities served” (Markless & Streatfield, 2006). However,

for libraries these outcomes or consequences are difficult to capture, because

they may be quite intangible or the library may only make a contribution to an

outcome rather than a whole consequence. According to Oakleaf “libraries need

to define outcomes relevant to their institution and assess the extent to which

they are met”. This is easier said than done, but it was the approach taken

within this review.

In brief, the review

used a comprehensive search to locate research evidence on the value of any

type of library, information, or knowledge worker. Only studies that provided

evidence of librarians contributing to clear outcomes were included. Evidence

was found for the following four sectors: health, academic, public, and school.

Each sector favoured particular types of study designs; this included Return on

Investment studies (public libraries), correlational designs (school and

academic libraries), critical incident technique (school and health), surveys

(school and health), and mixed methods, quasi experiments, and randomised

controlled trials (RCTs) (academic and health). Although some designs are

suited to particular sectors, such as the Return on Investment (ROI) for public

libraries, all sectors have much to learn from each other. For example,

academic libraries could make better use of more rigorous designs such as RCTs

to evaluate information literacy, and other methods could be used alongside

correlational designs to strengthen the evidence found.

The review

concluded that library and information professionals contribute to a wide range

of outcomes in their sectors. These contributions are summarised in Table 2.

Table 2

Contributions of

Librariansb

|

Health librarians contribute to… |

Academic librarians contribute to… |

Public librarians contribute to… |

School librarians contribute to… |

|

Improving the quality

of patient care |

Better research,

researchers, and research achievement |

Helping people to

feel a sense of belonging in their community |

Improving student

achievement |

|

Improving clinical

decision-making |

Better grades or

degrees |

Improving attitudes

to reading |

Improving reading

skills |

|

Improving patient

centred care |

A good return on

investment for the university |

A good return on

investment |

Facilitating student

learning |

|

Aiding risk

management and safety |

Improved retention |

Helping people

improve education and employment prospects |

Positive pupil

engagement |

|

Helping to

demonstrate efficiency and cost effectiveness |

|

Helping people

improve their health |

|

|

Health service

development and delivery |

|

|

|

|

Assisting health

professionals to pursue Continuing Professional Development |

|

|

|

b(Brettle &

Maden, 2016)

Creating the

Evidence

One of the recommendations

from the above scoping review (Brettle & Maden, 2016) recommended that

health libraries should improve standards for reporting impact studies. Within

the UK, the Knowledge for Health Quality and Impact Group have established a

project across all English hospital library services that seeks to do this. All

libraries working within the English National Health Service (NHS) are part of

the Knowledge for Healthcare Framework, which sets service standards and

monitors them regularly using an NHS Library Quality Assurance Framework (LQAF)

(http://www.libraryservices.nhs.uk/forlibrarystaff/lqaf/lqaf.html).

In relation to

demonstrating impact, the framework requires “evidence that a variety of

methods have been used to systematically gather information about the impact of

library services and that the information has been used to demonstrate the

impact of services”. Libraries use a wide range of methods to do this, and guidance

has been developed to help them provide high quality evidence (Weightman et

al., 2009). A survey showed that this guidance is not widely used and that most

libraries develop their own questionnaires.

This means that there is little rigour within each questionnaire, and

that an opportunity has been missed to compile results across the whole English

hospital library service using the same tools. To address these issues a

toolkit has been developed that provides access to guidance on measuring impact,

as well as a suite of simple, generic tools that librarians can routinely use

to measure impact and disseminate evidence about their services

(http://kfh.libraryservices.nhs.uk/value-and-impact-toolkit/). These tools use

an outcomes approach to collecting evidence.

A pilot of one of

the tools (a simple generic questionnaire) provided evidence of impact that

could be used by a range of stakeholders. For example, responses to one question

provide evidence of how the library is being used (what services), which is

likely to be of use to library managers. The highest uses of the library were

literature search services, study space, article or book supply, and training.

In contrast, use of current awareness services was low. This evidence can help

a manager decide where best to direct resources within the service. In relation

to how the information from the library was used, the pilot showed that information from the library is being used

for direct patient care (40%), to provide help to patients and families (27%),

for organizational development (15%), and for legal and ethical questions (9%).

This shows that the library clearly contributes in a wide number of ways to its

parent organization. This type of

evidence could be crucial to keeping the library open in times of financial

constraint and budgetary cuts.

An interview

template is also provided as part of the toolkit, to enable libraries to

collect evidence of more detailed outcomes and to explain how some of the

contributions are really made by libraries. This evidence can be disseminated

using a case study template, and case studies are being collated at a national

level (http://kfh.libraryservices.nhs.uk/value-and-impact-toolkit/kfh-impact-tools/impact-case-studies/). These can be used in a range of ways to

demonstrate the value and impact of libraries.

Evidence for Advocacy

The case studies

described above are being used as part of a high level social media campaign to

demonstrate the value and impact of health librarians. The campaign is called #amilliondecisions

and it uses Twitter to promote the evidence provided by health librarians to

support healthcare decision-making. One example highlighted how evidence from

health librarians contributed to a change in practice that reduced “Do Not

Attends” by 2% at clinics and reduced clinic waiting times by two weeks (http://kfh.libraryservices.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/DNA.jpg).

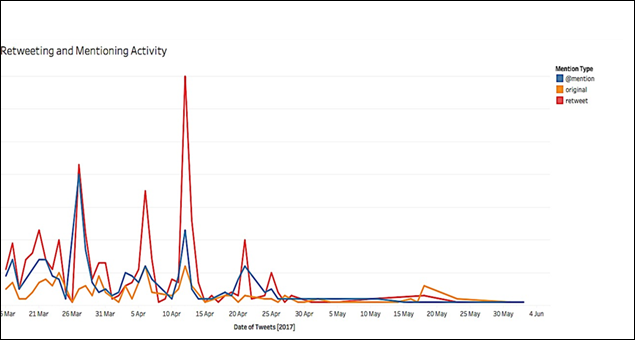

At the University

of Salford, UK, staff are currently taking part in a project to improve skills

in analyzing data from social media. Using Tableau software, staff tracked the

#amilliondecisions to provide evidence of who tweeted the most, what tweets had

the most impact, as well as the overall activity of the hashtag. Figure 1

clearly shows peaks and troughs in activity, including when all tweets had to be stopped due to the UK general

election campaign. This is a simple means of collecting evidence about a

campaign that can be used by those running the campaign to see its value and

where best to target their resources.

Figure 1

Evidence on the

value of social media campaign

Conclusion

Librarians make a

wide range of contributions to the organisations they serve, but it is often

difficult to articulate these and demonstrate their impact and value. Using

evidence about the outcomes to which libraries or librarians contribute is one

way forward. This paper highlights the different types of evidence that

librarians can gather or use to demonstrate their impact or value; this may be

research evidence or evidence that has been generated locally through

evaluation. Within the U.K. health library sector a number of initiatives are

taking place to help libraries collect impact data that can be used on a local

or national level to demonstrate impact to a wide range of stakeholders. By

doing this, U.K. health libraries are becoming evidence based. Although these

examples are UK based and within the health sector, this approach can be easily

adapted by libraries within other sectors.

References

Brettle, A., &

Maden, M. (2016). What evidence is there to support the

employment of trained and professionally registered library, information and

knowledge workers? A systematic scoping review of the evidence. London:

CILIP. https://archive.cilip.org.uk/sites/default/files/media/document/2017/value_of_trained_lik_workers_final_211215_0.pdf

Koufogiannakis, D., & Brettle, A.

(eds.). (2016). Being evidence based in

library and information practice. London: Facet Publishing.

Koufogiannakis, D. (2011). Considering the

place of practice-based evidence within evidence based library and information

practice (EBLIP). Library and Information

Research, 35(111), 41-58. http://www.lirgjournal.org.uk/lir/ojs/index.php/lir/article/view/486/527

Markless, S., & Streatfield, D.

(2006). Evaluating the impact of your

library. London: Facet

Publishing.

Oakleaf, M. (2010). The value of academic libraries:

A comprehensive research review and report (0004-8623). Chicago, IL:

Association of College and Research Libraries. http://www.ala.org/acrl/sites/ala.org.acrl/files/content/issues/value/val_report.pdf

Weightman, A., Urquhart, C., Spink, S.,

Thomas, R., and on behalf of the National Library for Health Library Services

Development Group. (2009). The value and impact of information provided through

library services for patient care: Developing guidance for best practice. Health Information & Libraries Journal,

26(1), 63-71. http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-1842.2008.00782.x