Research Article

Assessing the Impact of Reference Assistance and

Library Instruction on Retention and Grades Using Student Tracking Technology

Dennis Krieb

Director, Institutional

Research and Library Services

Reid Memorial Library

Lewis & Clark Community

College

Godfrey, Illinois, United

States of America

Email: dkrieb@lc.edu

Received: 1 Jan. 2018 Accepted: 12 Apr. 2018

2018 Krieb. This is an Open Access article

distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

2018 Krieb. This is an Open Access article

distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

Abstract

Objective – To assess the impact of community

college academic librarians upon student retention and grades through reference

desk visits and attendance in library instruction classes.

Methods –

Student ID data used for this research was collected from students that visited

the reference desk to consult about a course-related question or attended a

library instruction class for a specific course. After consenting to share

their student ID number, the students’ IDs were scanned and uploaded to a

Blackboard Analytics data warehouse. A Pyramid Analytics reporting tool was

used to query and extract student-level retention and grade data based upon

whether the student had visited the reference desk or attended a library

instruction class. Chi-square and Fisher’s exact tests were used to discern any

statistical difference in retention rates and grades between students that

engaged a librarian through reference or instruction and the general student

population.

Results – When

comparing fall-to-fall retention for all degree-seeking students, students that

visited the reference desk or attended a library instruction class had a

statistically higher rate of retention. When comparing fall-to-fall retention

within low-retention student cohorts, students that visited the reference desk

or attended a library instruction class had higher rates of retention. Rates of

retention in 8 of 10 cohorts were statistically higher for library instruction

and in 6 of 10 cohorts were statistically higher for reference visits. With

respect to course grades, only one of five high enrollment courses showed a

higher grade average for students that attended a library instruction class.

None of the differences in average grades between students that attended a

library instruction class and all students in the five courses were

statistically significant. For the impact of a reference visit upon a course

grade, all five courses showed a higher average grade average for students that

visited the reference desk for a question related to their course than for all

students in the course. Four of the five differences were statistically

significant.

Conclusions – The data

collected by systematically tracking students that interact with community

college librarians suggests that reference desk visits and attendance of

library instruction classes both have a positive statistically significant

impact upon student retention. When looking at course grades, the data does not

indicate a statistically significant positive or negative impact for library

instruction. The impact of visiting the reference desk upon course grades does

suggest a strong statistically significant positive correlation.

Introduction

Lewis

& Clark Community College is a two-year higher education institution

located in Godfrey, Illinois. Lewis & Clark has multiple campuses, a river

research center, a humanities center, a training center, and Community

Education Centers located throughout the more than 220,000-person college

district that reaches into 7 counties in Southwestern Illinois. Unduplicated,

degree-seeking enrollment for academic year 2016-2017 was 7,673 students.

The

confluence of reductions in state-level funding and declining student

enrollments has generated a sense of urgency upon student retention efforts at

Lewis & Clark Community College. In the years from 2006 to 2011,

fall-to-fall retention for full-time students dropped from 57% to 52%, and from 42% to 39% for part-time students. These data

mirror the low retention rates of all two-year community colleges, where nearly

50% of students leave by the end of their first year of enrollment (Hongwei, 2015). Within this challenging environment, there

began a new emphasis by state-level education agencies and higher education

accreditors for evidence based initiatives supporting student success.

To

address the demand for more evidence of success, a new approach to leverage

data was decided upon by administrators in Academic Affairs, Enrollment

Services, and Institutional Research. A campus culture would be cultivated that

relied heavily upon quantitative student assessment of innovative practices

using predefined measures of success. This approach would also explore student

tracking of support services on campus as a means to better understand the

impact of these services upon student success measures.

In

2012, the Student Success Team was established to address success initiatives

related to grades and retention. Members of the Student Success Team included

senior level academic administrators and members of the Institutional Research

department. The Student Success Team would act as an academic think tank to

investigate, pilot, and assess trends in higher education associated with

evidence based practices to improve student success.

The

Student Integration Model developed by Vincent Tinto suggests that supportive

social and educational communities outside of the classroom have a positive

impact upon student retention (Tinto, 2012). It was upon this theoretical

framework that the Student Success Team began to investigate the impact of

student support services at Lewis & Clark upon grades and retention.

The

first student support service selected by the Student Success Team to

investigate was academic tutoring. Branded as the Student Success Center,

tutoring at Lewis & Clark is decentralized among various campus locations.

Reid Library also hosts a Student Success Center location that provides

assistance for students seeking tutoring in writing and study skills. In 2013,

students that were tutored at any Student Success Center location were tracked

to discern the impact of tutoring upon retention. The fall-to-fall retention

rate for degree-seeking students enrolled in Fall 2013

that were tutored was found to be 65.6% (N=640), as compared to the overall

retention rate for all degree-seeking students of 51.5% (N=5085).

The

Student Success Team decided to expand the research of Tinto’s Student

Integration Model to Reid Library in 2014. This decision was supported by

research connecting the services and collections of academic libraries to Tinto’s

Student Integration Model (Oakleaf, 2010).

Correlational evidence linking student retention and academic success with

academic libraries published by the University of Minnesota (Soria, Fransen, & Nackerud, 2013)

was also instrumental in the Student Success Team’s decision to investigate the

impact of Reid Library upon student grades and retention.

Another

aspect of the Student Success Team work would be its emphasis on evidence based

research using Lewis & Clark’s technology infrastructure. A data warehouse

had recently been implemented, providing the ability to quickly identify

calculated success measures such as grades and retention for specific student

cohorts. A list of ten student cohorts with retention rates below the overall

student retention rate would be used to assess the impact of Tinto’s Student

Integration Model within Reid Library.

Table

1

Student

Demographics - Lewis & Clark Community College, Fall

2017

|

Student Type

|

Percentage

|

|

White

|

80.2%

|

|

African-American

|

9.8%

|

|

Hispanic

|

2.3%

|

|

Female

|

60.5%

|

|

18-19

Years of Age

|

36.1%

|

|

20-24

Years of Age

|

33.2%

|

|

First

Generation College

|

24.7%

|

|

Developmental

Math or English Placement

|

53.0%

|

|

Accepted

Pell Grant

|

39.2%

|

|

Veteran

|

3.7%

|

Literature Review

There

exists a crisis in retention and completion that is unique to community

colleges. Approximately 51% of all entering community college students will

have dropped out within their first year (National Student Clearinghouse

Research Center, 2016), and only 20% seeking to transfer to a four-year

institution will eventually do so (Lloyd & Eckhardt,

2010). For minority and part-time students, retention and completion are often

lower when compared to other community college students (Strayhorn, 2012).

In

his classic work Leaving College,

Vincent Tinto (2012) suggests that student attrition in postsecondary education

is related to a student’s immersion within the greater campus community.

“Institutions of higher education are not unlike other human communities, and

the process of educational departure is not substantially different from the

other processes of leaving which occur among human communities generally” (p.

204). Student support services help foster a campus community of belonging by

creating social relationships, clarifying aspirations and enhancing commitment,

developing college know-how, and making college life feasible (Karp, 2011).

Research

applying Tinto’s theoretical framework of student integration to various

student support services has yielded positive correlational relationships

between these services and student retention. Derby (2006) discovered a

significant positive relationship between student club participation and

retention and degree completion. The research of Grillo

and Leist (2013) with student academic tutoring also

discovered a positive relationship between tutoring and student retention and

completion.

Research

seeking to assess the academic library as a factor for increasing student

success metrics such as retention and completion is still a relatively new

field of study. Early studies often looked at aggregated data sets to discern

any correlational relationships between library input and output measures with

institutional retention and completion rates. Mezick’s

(2007) study found a positive relationship between total library expenditures

and student retention for postsecondary institutions offering a baccalaureate

degree. A positive relationship between library professional staff and student

retention was also found in the research of Emmons and Wilkinson (2011) when

analyzing data sets taken from the 2005-2006

Annual Survey of ARL Statistics.

With

the recent introduction of predictive and learning analytics within higher

education, institutions are now seeking more nuanced data to forecast student

behaviour to proactively engage students to improve student success measures (Lourens & Bleazard, 2016).

For academic libraries, this new emphasis upon predictive and learning

analytics represents a need to rethink how data is collected and how librarians

can connect academic library outcomes to institutional outcomes such as

retention and graduation (Oakleaf, 2010).

One

of the first major studies looking into student-level interactions with

academic library services and collections was conducted at the University of

Minnesota. This research involved collecting student-level data from students

that interacted with or used a library service or collection and connecting

these data to the students’ subsequent enrollment and grade point averages.

Findings from this research suggested that first-year students that used the

library had a higher grade point average and fall-to-spring retention rate than

their peers that did not use the library (Soria, Fransen,

& Nackerud, 2013). An additional study at the

University of Minnesota discovered that first-year students that used

electronic resources and books had higher odds of graduating over withdrawing

(Soria, Fransen, & Nackerud,

2013).

The

research shared in this paper applies the student-level approach to tracking

student engagement with the library, much like the work published by the

University of Minnesota. It is hoped that the findings in this research will

add to the literature regarding predictive analytics within academic libraries,

the technology infrastructure needed to systematically track students that use

the library, and the impact of library services – specifically, reference desk

encounters and library instruction classes – upon retention and grades.

Methods

As

previously mentioned in the literature review section, the research of Soria, Fransen, and Nackerud (2013) at

the University of Minnesota was one of the first published articles to apply

student-level tracking data from an academic library to investigate the impact

of librarians, services, and collections upon student success measures. This

seminal research served as the model for establishing the methods and measures

for this paper. By applying the methodology used in the University of Minnesota

study, a comparison of findings can be made between a two-year community

college and major research university.

Independent

and Dependent Variables

In

2014, Reid Library began systematically tracking student use in the library.

Two library service areas would serve as independent variables: 1) attendance

of a library instruction class and 2) visiting the reference desk for

assistance. A threshold was established that only reference questions

associated with an enrolled course would be tracked; directional and other non-course

related questions would not be measured for their impact upon retention and

grades. There were two dependent variables used in this research: 1)

fall-to-fall retention and 2) student grades for five courses having the

highest association with reference desk questions and library instruction. All

students in this research had a degree-seeking status.

Data

Collection

A

fundamental component of Lewis & Clark’s evidence based research is its

technology infrastructure. Central to

this architecture is the Blackboard Analytics data warehouse. The data

warehouse serves as a data repository, housing data tables related to student

characteristics, enrollments, grades, and completions from the Ellucian Student Information System (SIS). The Pyramid

Analytics reporting tool provides the ability to query the data warehouse for

calculated student success measures based upon treatments or services the

student may have received.

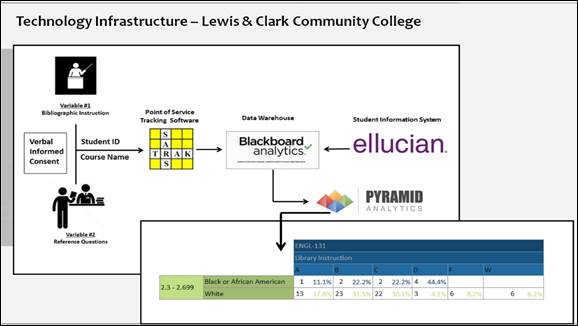

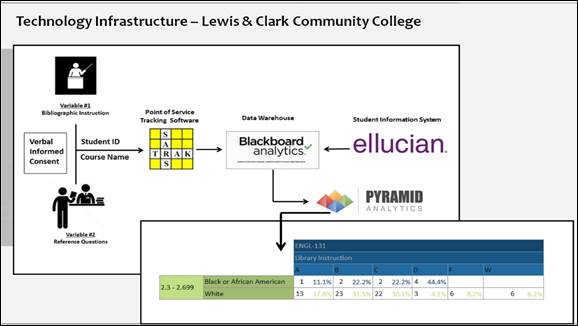

The technology infrastructure showing how student

tracking data is merged with student data retrieved from the SIS is depicted in

Figure 1. After a library instruction class or reference visit was completed,

the librarian asked for permission from the student to track his or her

attendance or visit. This is commonly known as a verbal informed consent. The

librarian explained to the student that no content-level information would be

recorded, only that they have either attended a library instruction class or

visited the reference desk. The student was informed that the data would only

be used for research purposes – including the possibility of sharing publicly –

to better understand student success metrics, and that no personally

identifiable information would ever be shared. Since the inception of this

pilot in 2014, no student has ever declined to be tracked.

Figure

1

Technology infrastructure for tracking

reference desk visits and library instruction attendance.

If the student agreed to share his or her student

ID and course information, the librarian used a barcode scanner or manually

entered the student ID in the tracking software. After entering the student ID,

a list of the student’s currently enrolled courses was provided by the tracking

software.

The librarian then selected the appropriate course

with which the library instruction class or reference visit was associated. The

tracking software platform used for this initial phase is called SARS

TRAK.

After scanning the student ID and selecting the

associated course, these data were sent to a Blackboard Analytics data

warehouse. Student data regarding grades, enrollment, demographics, and other

student-level data from the SIS were merged with the tracking data imported

from SARS TRAK within the data warehouse. A Pyramid Analytics reporting tool

was then used to query the data warehouse for calculated student success

measures based upon whether the student had visited the reference desk or

attended a library instruction course.

Results

Tables

2 and 3 compare the fall-to-fall retention rate for all degree-seeking students

for academic years 2014/15-2016/17 with the fall-to-fall retention rates of

degree-seeking students that attended a library instruction class or visited

the reference desk for the same time period. Students that attended a library

instruction class had a fall-to-fall retention rate of 60.9% (N=1,304), which

was higher than the overall retention rate of 48.8% (N=7,319) for all

degree-seeking students. Students that visited the reference desk had a

retention rate of 66.2% (N=215).

To

discern the impact of library instruction and reference assistance for students

having characteristics associated with lower retention rates, ten student

cohorts were identified as having lower retention rates than the retention rate

of 48.8% (N=7,319) for all degree-seeking students.

Table

4 shows the overall retention rate for each student cohort and the retention

rate for the students within each cohort that attended a library instruction

class or visited the reference desk. All 10 low retention student cohorts had a

higher rate of retention when attending a library instruction class or visiting

the reference desk, with 8 cohorts having a statistically significant difference

for library instruction and 6 cohorts statistically higher for reference.

Tables

5 and 6 compare the course grade success rates with library instruction and

reference desk visits. Success rates are defined at Lewis & Clark as a

grade of A, B, or C, and failure is a grade of D, F, or

W.

The

impact of library instruction on grades was minimal, with only one of the five

courses having a higher success rate than the overall course success rate.

Courses selected in Table 4 had the highest association of requiring attendance

of a library instruction class as part of the course. There was no

statistically significant difference in any of the success rates for the five

courses.

Courses

selected in Table 6 had the highest association with a reference question

relevant to the course. Unlike library instruction, students in all five

courses that visited the reference desk had a higher success rate than the

overall course

success rate. Four of the five courses had a statistically significant higher

success rate for those students that visited the reference desk for assistance

with their coursework.

Discussion

Testing

Tinto’s Student Integration Model in the context of librarian interactions with

students has provided Lewis & Clark Community College with correlational

evidence that relationships developed with college personnel outside of the

classroom are impactful for student success. With respect to the two

independent library variables tested in this research, both library instruction

and reference assistance were shown to have a positive statistically

significant correlational relationship with student retention. The

correlational relationship between library instruction and grades was not

established in this research; however, the data did reveal a positive

statistically significant correlation between reference assistance and grades.

Table

2

Fall-to-Fall

Retention Rate for All Degree-Seeking Students, Academic Years 2014/15-2016/17

|

|

N

|

Fall-to-Fall

Retention Rate

|

|

All Degree-Seeking Students

|

7,319

|

48.8%

|

N

represents a distinct student count.

Table

3

Fall-to-Fall

Retention Rates for Students Attending a Library Instruction Class or Visiting

the Reference Desk, Academic Years 2014/15-2016/17

|

N

|

Fall-to-Fall

Retention Rate

|

|

Attended a Library Instruction Class

|

1,304

|

60.9%**

|

|

Visited the

Reference Desk

|

215

|

66.2%**

|

N

represents a distinct student count.

* P<.05

**

P<.01

Table

4

Fall-to-Fall

Retention Rates for Student Cohorts with Low Retention Rates that Attended

Library Instruction or Visited the Reference Desk, Academic Years

2014/15-2016/17

|

Low Retention Cohort

|

N

|

Retention Rate- All Degree-Seeking Students

|

N

|

Retention

Rate-

Attended Library Instruction

|

N

|

Retention Rate-

Visited the Reference Desk

|

|

Cumulative GPA below 2.0

|

1,508

|

29.6%

|

120

|

34.1%

|

29

|

48.3%*

|

|

African- American

|

787

|

38.0%

|

150

|

46.4%*

|

37

|

59.5%**

|

|

Cumulative

GPA 2.0 - 2.29

|

3,509

|

40.2%

|

129

|

51.9%**

|

16

|

68.8%

|

|

Male

|

3,292

|

44.7%

|

543

|

57.7%**

|

70

|

65.7%**

|

|

Part-Time

|

4,963

|

45.1%

|

589

|

52.9%**

|

102

|

63.1%**

|

|

Age 20-24

|

2,569

|

45.4%

|

323

|

54.9%**

|

46

|

56.5%

|

|

First Generation

|

2,164

|

45.4%

|

217

|

54.4%**

|

49

|

62.0%

|

|

Developmental English Placement

|

327

|

45.6%

|

60

|

55.0%

|

16

|

58.8%

|

|

Pell Accepted

|

3,287

|

46.6%

|

660

|

54.1%**

|

123

|

59.7%**

|

|

Developmental Math Placement

|

2,337

|

47.0%

|

426

|

58.1%**

|

79

|

67.1%**

|

N

represents a distinct student count.

* P<.05

**

P<.01

Table

5

Course

Success Rates for the Highest Courses Associated with a Library Instruction

Class, Academic Years 2014/15-2016/17

|

N

|

Success Rate -

All Degree-Seeking Students

|

N

|

Success Rate -

Attended Library Instruction

|

|

Second Semester College English

|

1,568

|

70.8%

|

440

|

74.2%

|

|

First Semester College English

|

2,054

|

71.4%

|

396

|

69.6%

|

|

Public and Private Communication

|

1,692

|

80.3%

|

282

|

80.1%

|

|

Public Speaking

|

732

|

81.8%

|

127

|

78.9%

|

|

College Reading

(Developmental)

|

399

|

80.3%

|

93

|

80.2%

|

N

represents an enrolled course count.

* P<.05

**

P<.01

Table

6

Course

Success Rates for the Highest Courses Associated with a Reference Visit,

Academic

Years 2014/15-2016/17

|

N

|

Success Rate -

All Degree-Seeking Students

|

N

|

Success Rate -

Visited the Reference Desk

|

|

English 131

|

2,054

|

71.4%

|

102

|

85.3%**

|

|

English 132

|

1,568

|

70.8%

|

99

|

85.9%**

|

|

Reading 125

|

399

|

80.3%

|

32

|

96.9%*

|

|

Psychology 131

|

1,626

|

63.8%

|

31

|

77.4%

|

|

Art 130

|

597

|

72.7%

|

30

|

90.0%*

|

N

represents an enrolled course count.

* P<.05

**

P<.01

In

comparison to similar studies that tracked student use of academic libraries to

retention and grades, Soria, Fransen, and Nackerud’s (2013) research at the University of Minnesota

serves as the best example of a study using similar methods when comparing

library instruction and reference visits, though it should be noted that the

University of Minnesota is a selective admissions institution, unlike Lewis

& Clark Community College, which is an open admissions institution.

When

comparing the impact of library instruction upon grades, findings from the

University of Minnesota were similar to those discovered at Lewis & Clark,

with both showing a modest positive impact, though neither study found the

impact to be statistically significant. With respect to reference visits, the

University of Minnesota showed a positive correlation with grades, but without

statistical significance. Findings from Lewis & Clark showed statistically

significant higher grades in four of the five courses measured for students

that visited the reference desk.

Retention

comparisons for both studies found positive statistically significant

correlations between library instruction and student retention. Reference

visits in the University of Minnesota study showed a slightly negative

relationship with retention, though the data were not statistically

significant. Reference visits at Lewis & Clark were found to be positively

correlated with retention for all 10 cohorts studied, with 6 cohorts having a

statistically higher retention rate.

It

is interesting to note that a reference visit had a more significant impact

upon students at Lewis & Clark than for the students in the University of

Minnesota study. Because the setting of a reference visit is a one-on-one

encounter, an opportunity exists for the student to establish a relationship

with the librarian. For community college students at Lewis & Clark, 53% of

which are not prepared for college-level math or English courses, the need to

develop relationships with college personnel outside of the classroom may be

more impactful than for those students at a selective admissions university

like the University of Minnesota.

Another

observation taken from the findings is the higher impact of a reference visit

in comparison to attending a library instruction class for both grades and

retention at Lewis & Clark. Though a relationship may be developed between

a student and a librarian that teaches a library instruction class of 20 or 30

students, the likelihood of this occurrence is smaller than the opportunity for

a student to develop a relationship with a librarian through a reference visit.

Findings from this research would suggest that student proximity to a librarian

is correlated with grades and retention.

In

spite of the positive findings discovered in this study, there are limitations.

Students that visited the reference desk in this study represent a

self-selected sample. These students may be more academically motivated to

achieve higher grades and graduate than their classroom peers that did not

visit the reference desk. Future research into the impact of reference visits

upon grades and retention should consider propensity score matching of students

to reduce the potential for bias associated with student motivation.

Another

limitation of this study is the presumption that all reference desk visits are

equally weighted. The length of time spent during a reference desk visit may

also have a correlational relationship with grades and retention. Future

research should consider grouping reference desk visits by the length of the

interview.

Conclusion

Building

on the findings of this research, Lewis & Clark Community College has

expanded its tracking of students that interact with support services and

co-curricular activities to over 20 points of service, including tutoring,

advising, and participation in student life clubs and activities. The library

has also expanded its data collection by tracking students that check out items

from the collection. As with the current tracking system being used for library

instruction and reference assistance, student IDs will be used to identify

those students that circulate an item from the library. Data assessing the

correlational relationship between student use of the library’s non-digital

collection with grades and retention will be available in the fall semester of

2018. Moving forward, a campaign to proactively share the findings of this

research with faculty, students, and administrators at Lewis & Clark is

currently being planned in hopes of increasing overall student usage of the

library.

Incorporating

the library as a data resource for institutional research has been a goal for

the author of this paper. As a result of the research presented in this

article, the library has become a partner with peer divisions and departments

on campus with retention initiatives. A recent example is Lewis & Clark’s

requirement for accreditation to complete a four-year Quality Initiative to

improve retention for the Higher Learning Commission. Library findings

associated with the research in this paper will serve as a data source in the

Quality Initiative that seeks to explore Tinto’s Student Integration Theory

through student tracking of support services. Quality Initiative findings for

Lewis & Clark will be presented in 2020 at the Higher Learning Commission’s

Persistence and Completion Academy Results Forum.

It

should also be noted that the long-standing legacy of library patron privacy

has not been compromised in this research. No personally identifiable

information has been disclosed for any student tracked. All data are secured

within the institution’s Ellucian student information

system and are only accessible by the Institutional Research office at Lewis

& Clark Community College.

References

Derby,

D. C. (2006). Student involvement in clubs and organizations:

An exploratory study at a community college. Journal of Applied Research in

the Community College, 14(1), 39-45.

Emmons, M., & Wilkinson, F. C. (2011). The academic library impact on student

persistence. College & Research Libraries, 72(2),

128-149. https://doi.org/10.5860/crl-74r1

Grillo,

M. C., & Leist, C. W. (2013).

Academic support as a predictor of retention to graduation: New insights on the

role of tutoring, learning assistance, and supplemental instruction. Journal

of College Student Retention: Research, Theory & Practice, 15(3),

387-408. http://dx.doi.org/10.2190/CS.15.3.e

Hongwei,

Y. (2015). Student retention at two-year community colleges: A structural

equation modeling approach. International Journal of Continuing Education

& Lifelong Learning, 8(1), 85-101.

Karp, M. M.

(2011). How non-academic supports work:

Four mechanisms for improving student outcomes. CCRC Brief.

Number 54. Retrieved from https://ccrc.tc.columbia.edu/media/k2/attachments/how-non-academic-supports-work-brief.pdf

Lloyd, P. M., & Eckhardt, R. A. (2010). Strategies

for improving retention of community college students in the sciences. Science

Educator, 19(1), 33-41. Retrieved from https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ874152.pdf

Lourens,

A., & Bleazard, D. (2016). Applying predictive analytics in identifying students at risk: A

case study. South African Journal of Higher Education, 30(2),

129-142. http://dx.doi.org/10.20853/30-2-583

Mezick, E. M. (2007). Return

on investment: Libraries and student retention. Journal of Academic

Librarianship, 33(5), 561-566. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2007.05.002

National Student Clearinghouse

Research Center.

(2016). The role of community colleges in postsecondary

success: Community colleges outcomes report. Retrieved from https://studentclearinghouse.info/onestop/wp-content/uploads/Comm-Colleges-Outcomes-Report.pdf

Oakleaf, M. (2010). The value of academic

libraries: A comprehensive research review and report. Chicago: Association of College and Research

Libraries. Retrieved from http://www.ala.org/acrl/sites/ala.org.acrl/files/content/issues/value/val_report.pdf

Soria, K. M., Fransen, J., & Nackerud, S.

(2013). Library use and undergraduate student outcomes: New evidence for

students’ retention and academic success. portal: Libraries and the

Academy, 13(2), 147-164. https://doi.org/10.1353/pla.2013.0010

Soria,

K. M., Fransen, J., & Nackerud,

S. (2017). The impact of academic library resources on

undergraduates' degree completion. College & Research Libraries,

78(6), 812-823. https://doi.org/10.5860/crl.78.6.812

Strayhorn, T.

L. (2012). Satisfaction and retention among African American

men at two-year community colleges. Community College Journal of

Research and Practice, 36(5), 358-375. https://doi.org/10.1080/10668920902782508

Tinto,

V. (2012). Leaving college: Rethinking the causes and

cures of student attrition (2nd

ed.). Chicago, IL: University of

Chicago Press.

![]() 2018 Krieb. This is an Open Access article

distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

2018 Krieb. This is an Open Access article

distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.