Using Evidence in Practice

Terminology

for Librarian Help on the Home Page

Leni

Matthews

User

Experience Librarian

University

of Texas at Arlington

Arlington,

Texas, United States of America

Email:

leni@uta.edu

Received: 7 Feb. 2018 Accepted:

17 Apr. 2018

2018 Matthews.

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative

Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License

4.0 International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

2018 Matthews.

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative

Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License

4.0 International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

DOI: 10.18438/eblip29405

Setting

The University of

Texas at Arlington (UTA) is a public university serving over 40,000 students,

reaching nearly 50,000 when online students are calculated. There are three

libraries on campus: Central Library, Architecture and Fine Arts Library, and

Science and Engineering Library. Central Library has six floors including a

basement. Students in this study were recruited from all three libraries. UTA

libraries have a diverse user community and UTA itself was named one of the

most diverse campuses in the US in a study done by the US News and World Report

(2018).

Problem

Librarians at UTA began an email

conversation about terminology to use on the home page that is easy to

understand for users. One of our librarians stated that we should “include more

areas of expertise that work directly with our users” while creating language

that would make librarians findable on the home page. The librarians began to

propose terms they thought users would choose to search for them on the library

home page. Instead of weighing in on librarian-proposed terms from only

librarians, we decided to ask our user community since they are users or

potential users of the home page. To improve the way users access our

“expertise” for assistance, we must include them to understand their search

process.

Our librarians have backgrounds in areas

such as open educational resources (OER) and data literacy that exist outside

their normal duties. We want to market those skills to make our librarians more

accessible to users. First, we needed to figure out which labels users

preferred from the librarian-proposed terms when they searched for a librarian

on our home page. Were we generating user-friendly terminology that was

intuitive for librarian discoverability? We also wanted to figure out what they

expected to “see” once a particular label was chosen by asking their

expectations for the landing page. Determining this expectation would help us

discover users’ understanding of these labels.

Evidence

At UTA, the

Digital Creation and Assessment departments collaborated to conduct a usability

study to find out the terms users preferred when they searched for librarian

assistance on the home page. A paper prototype of the library home page was

used where students pointed to terms they thought would help them find librarians.

Term refers to the labels or language used on the home page that link to other

webpages. Librarians proposed terms they thought would help users to locate

them. These terms were shared via email and open to all twenty-one of our

librarians. Some librarians proposed new terms, while others agreed with some

of the suggested terms. We added these terms on the home page.

The paper

prototype looked similar to Figure 1.

There were a total

of 26 labels for the right side of the home page, including the terms proposed

by librarians. The dropdown menus were expanded on the paper prototype making

it easier to “navigate.” This paper will focus on the usability study for the

right-side of the home page. This is where the original term (Librarians by

Subject) that linked directly to librarians was located.

Librarians

proposed seven terms/labels they thought would be useful when users searched

for a librarian:

Librarians by

Subject (previous – before the usability test)

- Librarians by Academic Subject (current

– after the usability test)

- Librarians by Expertise

- Librarians by Academic Discipline

- Librarians by Area of Expertise

- Librarians by Specialty

- Areas of Expertise

- Assistance by Expertise

We recruited 14

students to participate in the usability testing. We asked the participants to

point to the label they would click on to find a librarian under two

circumstances: 1) seeking assistance in their major and 2) seeking assistance

outside their major.

Figure

1

Paper

prototype of the home page.

We presented the

paper prototype to each student and used a semi-structured approach, using a

set of questions as a guide, not a prescriptive, rigid survey. We asked

questions to identify their preferred labels and what they expected to see on

that landing page. We identified two possible search questions that correspond

with the above circumstances. Students may have these questions in mind when

seeking librarian assistance:

- When looking for help from a

librarian for information related to your major, what link would you

choose?

- When looking for help from a

librarian for information outside your major, what link would you choose?

With this

user-centered approach we were able to gather students’ preferences for labels

when seeking librarian assistance. While we considered asking student workers,

we knew that students who work for the library may be biased or have a better

understanding of searching for librarian assistance, since they work with

librarians almost daily. Because of this knowledge, we decided to ask random

students in the library.

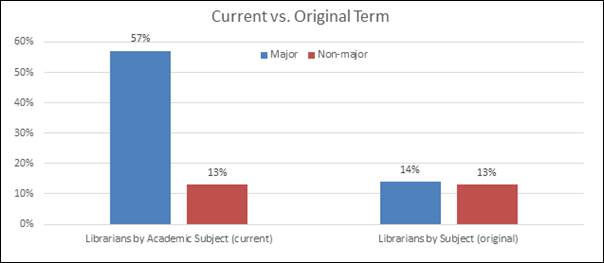

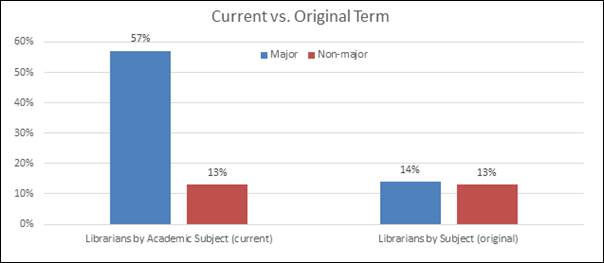

“Librarians by

Academic Subject” was chosen most often (Table 1). This label was chosen at a

higher rate for question one, relating to their major, which may be obvious

because of the word “academic.” However, the amount of clicks it received was

unexpected. Language made a significant difference in how students searched.

There was no

difference when comparing the current and original labels for question 2:

searching for librarian help outside their major (Figure 2. red bars). We can

assume that there needs to be specific language that affords this type of

search, especially if librarians want to market their various skills to

students.

Once a term was

“clicked,” students were asked what they expected to see on the following page.

We wanted to find out what they thought they would discover once they chose a

link. Students expected to see similar information on these landing pages

across all librarian-proposed terms.

Expectations included seeing a list of librarians, college departments

by major, and librarian contact information. When “Librarians by Expertise” was

chosen, one student commented that they expected the librarian to have a MA or

PhD in that subject.

Fessenden’s (2010)

eye tracking study found that 80% of web users look at the left side of the

screen while 20% look at the right side of the screen. Our usability study

showed that students chose labels most often from the right side of the screen.

However, this does not negate the fact that they may have mostly looked on the

left side of the screen. Eye tracking could have been useful to find out where

students look for discoverability of librarians, but it was not part of our

study. According to Pernice (2017) users’ motivation

impacts what they click. So, our users’ choice in labels may have been impacted

by the two questions asked as opposed to finding labels under actual

circumstances.

Involving students

in this study to gather feedback about how they search the library home page

was more user-centered than allowing librarians to assume how users search. Our

actual or potential users were our best resource for evidence.

Implementation

On the UTA library

website, “Librarians by Subject” was changed to “Librarians by Academic

Subject” based on the usability testing conducted. The Digital Creation

department made changes to the website within weeks of providing the findings

from the paper prototypes. No other website changes were made at that time.

The evidence from

students showed us their preferred language when searching for librarians. The

implementation of this new, or rather improved label was intended to clarify

language and meaning as it relates to seeking librarians on the home page.

Table 1

The Percentage of Label Clicksa

|

PROPOSED TERMS

|

TOTAL PERCENTAGE OF

CLICKS

|

|

Librarians by Academic Subject (Current term)

|

30%

|

|

Librarians by Expertise

|

15%

|

|

Librarians by Academic Discipline

|

3%

|

|

Librarians by Area of Expertise

|

6%

|

|

Librarians by Specialty

|

9%

|

|

Areas of Expertise

|

6%

|

|

Assistance by Expertise

|

6%

|

|

Librarians by Subject (Original term)

|

12%

|

|

Ask Us

|

9%

|

|

Request an Appointment

|

3%

|

aLibrarian-proposed terms are shaded

Figure 2

Preference for terms on library home page.

Table

2

Page

Views for 2016 and 2017 for Subject Librarians

|

|

2016

June

– September

|

2017

June

– September

|

|

Page Views

|

1557

|

2199

|

Outcome

There was a 39%

increase in clicks for “Librarians by Academic Subject” from summer 2016 to

summer 2017 (see Table 2).

“Librarians by Academic Subject” received

32% of all page views, reiterating that the label change was successful.

However, when it came to finding librarian help outside the student’s major,

none of the librarian-proposed terms were strong contenders. “Librarians by

Expertise” received the greatest number of clicks (3 of 19 total clicks). Since

“Librarians by Academic Subject” received the most page views overall, it is a

starting point for placing those extra skills librarians have on that page, as

well as for better accessibility.

Students chose other labels from the

website as well, such as “Ask Us.” This shows that we are losing a portion of

our student population (12%) when they are seeking librarian assistance. Some

are not using the labels we expect them to use. Also, searching for librarian

assistance outside their major (Question 2) held no significant click rate for

any one particular label; the librarian-proposed labels were chosen one to two

times. This finding shows that we need better labels that are intuitive and

that resonate with students when they search for a librarian on the home page.

There was not a significant amount for any other librarian-proposed term chosen

outside of “Librarians by Academic Subject.” Was this because most of the

proposed terminology did not resonate with our users when searching for

librarian assistance?

Students also provided their own labels,

such as “Librarians by Research Interest,” “Librarian Assistance by Expertise”

and “Librarian Assistance by Specialty.” Further research would allow students

to create labels instead of choosing from terms generated by librarians.

According to Gillis (2017) knowing certain terms does make navigating easier,

but we must be aware that jargon can create obstacles for new users. Allowing

our users to create labels may make their search easier.

Reflection

The data

collection process was straightforward due to the consistency in questioning

and methodology.

This study could

be improved. The librarian-proposed terms were shown as a list and “Librarians

by Academic Subject” could have created a bias since it was the first listed.

To limit the amount of paper illustrating the various places for the

terminology, we decided to list the terms together, using one sheet. We could

also improve the way the study was implemented. For example, in the future, we

should ask students what they prefer, without presenting them with labels to

choose from. Their language, or suggestions for labels, strongly reflected

ours. They used similar terms as ours such as “expertise” and “specialty.”

Students’ suggested labels could have been influenced by the labels that were

presented to them, even those that were already on the website.

Optimally, the

usability study would be done on a computer, randomizing the locations of the

librarian proposed terms with students doing real-time research in the context

of what they are studying. Relating to our goal, the literature talks about

marketing or “effectively sharing” the services and expertise of librarians

(Benedetti, 2017). We want the best labels to be able to communicate to users

the range of skills that UTA librarians possess.

Our results are

satisfying, but more work should be done to simplify language for improved online

accessibility to meet users’ needs.

References

Benedetti, A. R.

(2017). Promoting library services with user-centered language. portal: Libraries and the Academy, 17(2), 217-234. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1353/pla.2017.0013

Fessenden, T. (2017). Horizontal attention leans

left. Retrieved from https://www.nngroup.com/articles/horizontal-attention-leans-left/

Gillis, R. (2017).

Watch your language: word choice in library website usability.

Partnership: The

Canadian Journal of Library and Information Practice Research, 12(1). Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.21083/partnership.v12i1.3918

Pernice, K. (2017). Eyetracking

shows how task scenarios influence where people look. Nielsen Norman Group. Video. Retrieved from https://www.nngroup.com/videos/eyetracking-task-scenarios/?utm_source=Alertbox&utm_campaign=eea3f842de-Newsletter_Imagery_Leading_Questions_2017_12_18&utm_medium=email&utm_term=0_7f29a2b335-eea3f842de-40289501

US News & World

Report (2018). Campus Ethnic Diversity. Retrieved from

https://www.usnews.com/best-colleges/rankings/national-universities/campus-ethnic-diversity

![]() 2018 Matthews.

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative

Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License

4.0 International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

2018 Matthews.

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative

Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License

4.0 International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.