Research Article

Relevance of a French National Database Dedicated to

Infection Prevention and Control (NosoBase®): A Three-Step Quality Evaluation

of a Specialized Bibliographic Database

Kae Ting Trouilloud

Infection Control Pharmacist

Mobile Infection Prevention Team for Nursing Homes (EMHE)

Lyon University Hospital (HCL)

Lyon, France

Email: kae.trouilloud@chu-lyon.fr

Nathalie Sanlaville

Librarian

Healthcare-Associated

Infection Prevention and Control Regional Coordinating Centre for

Auvergne-Rhone-Alpes (CPIAS ARA)

Lyon, France

Email: nathalie.sanlaville@chu-lyon.fr

Sandrine Yvars

Head of Documentation Center for Professionals

National Police Academy (ENSP)

Saint-Cyr-au-Mont-d’Or, France

Email: yvars.sandrine@wanadoo.fr

Anne Savey

Director (IPC)

Healthcare-Associated

Infection Prevention and Control Regional Coordinating Centre for

Auvergne-Rhone-Alpes (CPIAS ARA)

Lyon, France

Email: anne.savey@chu-lyon.fr

Received: 15 May 2018 Accepted: 16 Jan. 2019

![]() 2019 Ting Trouilloud, Sanlaville, Yvars, and Savey. This

is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

2019 Ting Trouilloud, Sanlaville, Yvars, and Savey. This

is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

DOI: 10.18438/eblip29448

Abstract

Objective

–

NosoBase® is a collection of documentation centres with a national

bibliographic database dedicated to infection prevention and control (IPC),

with over 20 years of experience in France. As a quality assurance activity,

this study was conducted in 2017 with a three-step approach to evaluate the

bibliographic database regarding (1) the availability and coverage of

citations; (2) the scope and relevance of content; and (3) the quality of the

documentation centre services.

Methods

– The three-step quality approach

involved (1) evaluating the availability and coverage of citations in NosoBase®

by searching for the bibliographic citations of three systematic reviews on hand

hygiene practices, published recently in three different peer-reviewed

international journals; (2) evaluating the scope and relevance of content in

NosoBase® by searching for all documents from 2015 indexed in NosoBase® under

hand hygiene related keywords, and analyzing according to publication language,

document type (e.g., legislation, research, or guidelines), and target

audience; and 3) evaluating the strengths, weaknesses, and opportunities of the

documentation centre services, with interviews involving the librarians.

Results

–

NosoBase® contained 70.8%-80.9% of references directly concerning hand hygiene

cited by the three systematic reviews. Of the 200 articles indexed in NosoBase®

under hand hygiene related keywords in 2015, 22.5% were French language based,

with a significant representation of French non-indexed literature. The

analysis of the documentation centre services highlighted future opportunities

for growth, building on the strengths of experience and collaborations, to

improve marketing and usability, targeting francophone IPC professionals.

Conclusion

–

Specialized bibliographic databases may be useful and time efficient for the

retrieval of relevant specialized content. NosoBase® has significant relevance

to French and francophone healthcare professionals in its representation of

French documentation and healthcare literature not otherwise indexed

internationally. NosoBase® needs to highlight its resources and adapt its

services to allow easier access to its content.

Introduction

With the growing emphasis on evidence based practice,

more databases and research content are now being made available. Yet it is

often difficult and time-consuming for clinicians and researchers to locate

relevant literature even if it is more accessible. Studies indicate that

searches only on Google Scholar may not be enough (Boeker, Vach, &

Motschall, 2013), and that searches on multiple databases are often necessary

for finding relevant bibliographic content (Rathbone, Carter, Hoffmann, &

Glasziou, 2016). One earlier study compared several health-related databases

(CINAHL, Cochrane Library, MEDLINE, PsycLIT, Sociofile, and Social Science

Citation Index), and found that PsycLIT was the most useful database for

information on the rehabilitation of people with severe mental illness in terms

of search efficiency and relevance in this topic area, highlighting the

importance of a specialized bibliographic database (Brettle & Long, 2001).

More recently, Rethlefsen, Murad, and Livingston (2014) proposed that human-indexed

databases allow faster, more comprehensive searching in terms of terminology

and controlled vocabulary structure than solely computer algorithm-indexed

databases such as Scopus and Google Scholar, despite search engines that search

full-text articles in the latter. The impact of trained searching and

assistance from trained information professionals and librarians has also been

underlined (Centre for Reviews and Dissemination, 2009). Librarian co-authors

correlated with higher quality reported search strategies in general internal

medicine systematic reviews, leading to a more comprehensive, true systematic

review (Rethlefsen, Farrell,

Osterhaus Trzasko, & Brigham, 2015).

As a quality assurance activity, this study evaluated

NosoBase®. Created in 1996, NosoBase® is a national project focused on

infection prevention and control (IPC) in healthcare settings (Savey, Sanlaville,

& Fabry, 2000). It consists of five documentation centres,

with trained librarians located in different cities in France (Lyon, Paris,

Rennes, Bordeaux, and Nancy). It hosts a forum for IPC professionals and a

website with resources and tools. There are collaborations with national

medical or professional IPC learned societies, cooperation with other

libraries, and bibliographic support to the national public health agency.

Based in the French language, it manages a bibliographic database also known as

NosoBase®, indexing up to 180 journals in multiple languages. This study

describes a three-step quality assessment conducted in 2017 to evaluate the

content of the database (steps 1 and 2) and the documentation centre services

(step 3).

Literature

Review

Bibliographic databases came into being in the 19th

and 20th centuries in response to the proliferation of journals and other

publications, then went online in the late 20th century (Glasziou

& Aronson, 2017). Specialized (or subject-specific) bibliographic databases

are now available in diverse fields, from chemistry (Chemical Abstract Service)

to psychology, psychiatry, and neurology (PsycINFO); from nursing and caring

sciences (CINAHL) to geology (GeoBase) (Gasparyan et al., 2016). Many offer

access mainly through subscription or through membership in professional

associations. In France, bibliographic databases such as Pascal & Francis

and the public health database Banque de Données en Santé Publique (BDSP) were

developed in the 1970s and 1990s, respectively. It was noted that in the Pascal

database, around 12% of the journals indexed were French language based, and

55% of the journals indexed were not available in PubMed (Dufour, Mancini,

& Fieschi, 2009).

However, bibliographic databases and the documentation

centres that maintain them currently face growing costs for maintenance and

rising competition from multidisciplinary databases such as PubMed that provide

free online access. Researchers began to compare recall efficacy between

multidisciplinary databases and specialized databases. One case study used a

systematic review to investigate the performance of bibliographic databases in

identifying the included studies. Its results showed that the use of at least

two databases and reference checking were required to retrieve all included

studies (Beyer & Wright, 2013). Another study examined the yield of

MEDLINE, EMBASE, and CENTRAL to find randomized controlled trials within the

area of musculoskeletal disorders. It found that searching all three databases

was not sufficient for identifying all effect studies on musculoskeletal

disorders, though an additional 10 databases did only increase the median

recall by 2% (Aagaard, Lund, & Juhl, 2016).

In France, the National Conservatory of Arts and

Crafts and National Institute for Documentation Techniques (CNAM INTD, http://intd.cnam.fr/)

developed methodologies to evaluate documentation centre services. These

methodologies focused mainly on the organization of resources and processes and

evaluating the management of the information systems, with an emphasis on

quality assurance activity built into the process. Quality indicators and

action plans are identified to improve client satisfaction and overall

documentation quality and service quality.

In the 1990s, there was also a progression towards

practices based on evidence, or evidence based practice, and medicine was at

the origin of this movement (Goodman, 2002). Libraries and documentation

centres have joined the movement, examining the management of documents and

information based on evidence, an approach known as evidence based librarianship

(Booth & Brice, 2004). An example of this was a systematic review conducted

in 2010, which examined models of clinician services and evaluated the value of

their service towards clinicians. It described clinician libraries having a

positive impact on patient care, resulting in better informed decisions on

choices of drugs or therapy, and saving clinicians’ time (Brettle et al.,

2011).

However, during the same year, the dramatic evolution

of information technologies led to a reexamination of the librarian role and a

reevaluation of core competences by the Canadian Association of Research

Libraries (2010). With the rise of Google and internet access, studies also

described changes in scholar and student information-seeking behavior (Jamali

& Asadi, 2010). A recent study indicated that the coverage of Google Scholar is

improving (Gehanno, Rollin, & Darmoni, 2013). However, the findings of this

study have been disputed. Guistini and Kamel Boulos (2013) noted that Google

Scholar was still unreliable for searching systematic reviews due to its

constantly changing content, algorithms, and database structure. Other studies

found that Google Scholar missed important literature in evidence reviews and

grey literature searching (Haddaway, Collins, Coughlin, & Kirk, 2015) or

that it presented incomplete recall (Bramer, Giustini, Kramer, & Anderson,

2013).

In France, websites and portals in the French language

dedicated to health literature have been in place for some time, such as

CISMeF, Recomedical, BIU Santé Paris, and BDSP, a database for public health

hosted by the national public health higher learning institution Ecole des

Hautes Etudes en Santé Publique (EHESP) in Rennes. However, funding for BDSP

has been greatly limited recently.

Aims

After more than 20 years of experience, the librarians

of the documentation centre NosoBase® wanted to assess the quality and the

usefulness of the services and tools provided. This study was conducted in 2017

with a three-step process to evaluate the bibliographic database NosoBase®

regarding (1) the availability and coverage of citations and (2) the scope and

relevance of content, as well as (3) the quality of the NosoBase® documentation

centre services.

Methods

A three-step quality assessment was used in order to evaluate

the content of the database and the documentation centre services. Step 1

evaluated the availability and coverage of citations in NosoBase® through

searching for bibliographic citations of three systematic reviews on hand

hygiene practices, which were published recently in three different

peer-reviewed international journals. Step 2 evaluated the scope and relevance

of content in NosoBase® by searching for all documents from 2015 indexed in

NosoBase® under hand hygiene related keywords, and analyzing them according to

publication language, document type (e.g., legislation, research, or

guidelines), and target audience. Step 3 evaluated the strengths, weaknesses,

and opportunities of the documentation centre services, with input from the

librarians.

Step 1: Availability and Coverage of Citations in

NosoBase®

The theme of hand hygiene was selected as it

represents an important aspect of IPC. Three systematic reviews on hand hygiene

practices were selected from a simple straightforward search on PubMed

(keywords: “hand hygiene systematic review” and “Cochrane AND hand hygiene

systematic review”) for the most recent publication on January 26, 2017,

representing three different peer-reviewed international medical journals.

Initially, the authors discussed the importance of including a Cochrane

systematic review, but at the time of searching none were found that fit the

criteria of date and theme. We have chosen to leave the keyword search

“Cochrane” here for transparency to reflect the search process. The three

selected reviews are listed below.

Review 1:

Musuuza, J. S., Barker, A., Ngam, C., Vellardita, L.,

& Safdar, N. (2016). Assessment of fidelity in interventions to improve

hand hygiene of healthcare workers: A systematic review. Infection Control & Hospital Epidemiology, 37(5), 567-575.

·

Search: PubMed, CINAHL, Cochrane, Web of Science, up

to 19 June 2015.

·

The review described limited electronic grey

literature searching (p. 568).

·

Keywords used: implementation fidelity, intervention

fidelity, intervention compliance, hand washing, hand hygiene, hand

disinfection.

·

120 citations; author affiliations: United States.

Review 2:

Kingston, L., O’Connell, N. H., & Dunne, C. P.

(2016). Hand hygiene-related clinical trials reported since 2010: A systematic

review. Journal of Hospital Infection, 92(4),

309-320.

·

Search: PubMed, CINAHL. Studies from the US and

Europe, from Dec 2009 (after the publication of the WHO hand hygiene

guidelines), up to Feb 2014.

·

The contact author confirmed that grey literature and

hand searching were not conducted for this study.

·

Keywords used: hand hygiene, hand washing,

observation, and clinical trial.

·

88 citations; author affiliations: Ireland.

Review 3:

Luangasanatip, N., Hongsuwan, M., Limmathurotsakul,

D., Lubell, Y., Lee, A. S., Harbarth, S., Day, N. P. J., Graves, N., & Cooper, B. S. (2015). Comparative efficacy of interventions to

promote hand hygiene in hospital: Systematic review and network meta-analysis. BMJ, 351, h3728.

·

Search: MEDLINE, Embase, CINAHL, NHS Economic

Evaluation Database, NHS Centre for Reviews & Dissemination, Cochrane, EPOC

register, studies from Dec 2009 to Feb 2014.

·

The review appendix listed only electronic searching.

·

Same keywords as former systematic reviews from 1980

to 2009.

·

89 citations; author affiliations: Thailand,

Australia, United Kingdom, Switzerland.

For each systematic review, all bibliographic

citations were listed on a spreadsheet indicating availability, whether

directly related to hand hygiene practices, and whether indexed under hand

hygiene keywords, with a note for comments. Their availability in the database

of NosoBase® was verified during February 2017.

Step 2: Scope and Relevance of Content in NosoBase®

A search was performed on February 9, 2017, for all

indexed documents under hand hygiene related keywords from the database of

NosoBase®. The year 2015 was chosen since publications from the end of 2016

were not yet completely indexed by February 2017. The documents were analyzed

according to the publication language and document type (e.g., legislation,

research article, or guidelines), as well as target audience.

Step 3: Quality Review of the Documentation Centre

Services

Using the National Conservatory of Arts and Crafts and

National Institute for Documentation Techniques (CNAM INTD, http://intd.cnam.fr/)

methodologies as models (Toneatti, 2008; Palisse, 2011), a qualitative

descriptive approach was chosen for this study, examining six categories:

communication, accessibility, production, management, marketing, and

opportunities, through a modified SWOT analysis (strengths, weaknesses, and

opportunities, with threats analyzed under weaknesses).

Semi-structured face-to-face discussions using the

modified SWOT analysis and categories were conducted with the on-site

librarians (co-authors) separately. Semi-structured discussions using the same

analysis and categories were conducted by the librarian co-authors with three

other librarians from the other NosoBase® documentation centres, during

regularly scheduled telephone conference meetings between February and July

2017, as part of the meeting agenda, and by electronic mail due to time and

geographical constraints. Report drafts resulting from input obtained during

the above discussions were created. The librarian meetings were not recorded

nor transcribed, but minutes were kept and circulated for verification, as per

normal practice. Ethics approval was not obtained as it was an internal quality

assurance exercise.

Results

Step 1: Availability and Coverage of Citations in

NosoBase®

There were a variety of citations included in the

bibliographies of the three systematic reviews, including articles on

methodology and economic impact (review 1); surveillance, good practice, and

psychology (review 2); and systematic review methodologies, meta-analysis,

statistics, and models (review 3). These and other non-hand hygiene related

references were included in the category “other.” Hand hygiene references were

defined as articles directly related to research in hand hygiene practices. See

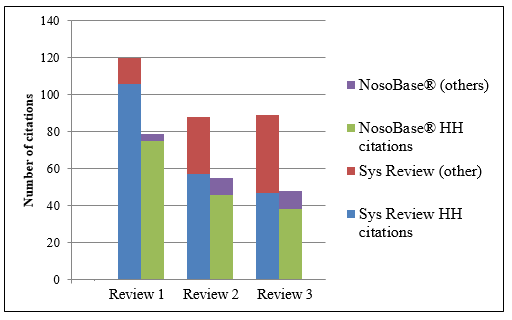

Table 1 and Figure 1 for the comparison between the three systematic reviews

and the database NosoBase®.

From Table 1, NosoBase® is shown to have indexed

70.8%, 80.7% and 80.9% of hand hygiene citations from each systematic review.

Articles that were not available in NosoBase® were mainly from specialized

nursing journals (e.g., Plastic Surgical

Nursing, Nursing Times, Critical Care Nursing Quarterly, Clinical Nursing Research, and The American Journal of Nursing) or

regional and national journals not in its repertoire or with a lower Scimago

ranking (e.g., Journal of the Medical

Association of Thailand, Annals of

the Royal College of Surgeons of England, Medical Journal of Australia, Scandinavian

Journal of Infectious Diseases, and Life

Science Journal - Acta Zhenzhou University Overseas Edition). See Scimago, https://www.scimagojr.com/.

Table 1

Number of Citations (All or Hand Hygiene/HH), from the

Three Systematic Reviews, versus Number of Citations Available in NosoBase®

|

|

Systematic review |

Availability in NosoBase® |

|||||

|

|

All citations |

HH citations |

All citations |

HH citations |

|||

|

|

Number (n) |

n |

% |

n |

% |

n |

% |

|

Review 1 |

120 |

106 |

88.3 |

79 |

65.8 |

75 |

70.8 |

|

Review 2 |

88 |

57 |

64.8 |

55 |

62.5 |

46 |

80.7 |

|

Review 3 |

89 |

47 |

52.8 |

48 |

53.9 |

38 |

80.9 |

Figure 1

Number of citations (All or Hand Hygiene/HH

citations), from the three systematic reviews, versus number of citations

available in NosoBase®.

The contact author for each systematic review

confirmed that the literature search was carried out either by information professionals/librarians,

or by researchers previously trained by them. The contact authors for Reviews 1

and 3 did not confirm whether grey literature searching was done. The contact

author for Review 2 confirmed that a grey literature search was undertaken. Of

the three systematic reviews, all three searched PubMed/MEDLINE but none

searched Google Scholar. It was interesting to note that across the three

systematic reviews, 10 references were cited by two reviews. Only two references

were cited by all three systematic reviews.

Step 2: Scope and Relevance of Content in NosoBase®

Of the 200 documents indexed in NosoBase® in 2015 with

hand hygiene keywords, the majority were research articles. Out of 200 items,

45 (22.5%) were published in French. The following French journals were

represented: Aide-soignante, Hygiènes,

Inter-bloc, Noso-info, Pratiques psychologiques, Risques et qualité en milieu

de soins, Soins aides-soignantes, Soins, and national infection control

bulletins. A majority of these journals are not indexed in commercial or other

well-known databases.

The documents listed included four legislative texts

from the Public Health Council (HCSP), the French National Organization for

Standardization (AFNOR), and the French Republic Official Journal (Journal officiel de la République française).

Also included were guidelines from the World Health Organization (WHO), the

Cochrane Library, the National IPC Learned Society (SF2H), and the National

Institute of Public Health of Quebec.

The documents reflected a wide target audience,

including health professionals such as doctors, nurses, nursing assistants,

surgeons, anesthetists, radiologists, pharmacists, IPC specialists, laboratory

technicians, and general practitioners; as well as hospital managers, patients,

hospital visitors, medical or nursing students, medical researchers,

epidemiologists, the general public, and hospital engineers. Corresponding

healthcare structures included hospitals, nursing homes, community healthcare

centres, and training institutes.

Step 3: Quality Review of the Documentation Centre

Services

From the semi-structured discussions with the

librarians, the documentation centre services were described and summarized in

six categories according to strengths, weaknesses, and opportunities.

Communication

Regarding strengths in this area, there is a monthly

newsletter NosoVeille highlighting

new arrivals and publications (e.g., legislation) and a trimester thematic

publication NosoTheme in a French

professional IPC journal. Also, the brand NosoBase® and its documentation

services have become well known to IPC professionals for over the past 20

years. However, its current weaknesses include irregular social media presence

(e.g., in Twitter, Facebook, or YouTube), despite already having some presence

there. Its brand is also less well known outside of France. There is therefore

an opportunity for growth through increasing social media communication with

better frequency in more channels (e.g., LinkedIn), and exploring communication

channels outside of France.

Accessibility

In terms of accessibility, there is free online access

to the NosoBase® database and web resources, with phone and email access to

librarians for bibliographic aid and advice. However, the new database system

(transitioned in March 2017) required current users to adapt to the new

interface. There is also an urgent need for a search engine to access the

website resources due to data growth. The opportunities for improvement involve

facilitating access through user guides and facilitating website navigation and

searching through an efficient search engine.

Production

The strengths of NosoBase® lie in its rich collection

of French and multilingual documents (e.g., English, Spanish, and German);

diverse IPC related documentation (legislation, guidelines, and toolkits);

articles in multiple formats (paper and electronic); and a new generation

Functional Requirements for Bibliographic Records (FRBR) database system. It

also has a librarian curated specialized IPC thesaurus. However, there is a

lack of standardized internal procedures, and it was significantly

time-consuming to adapt and format the new database system. The thesaurus is

not updated regularly, and it needs to evolve along MeSH terms. There is

therefore opportunity for growth through streamlining and standardizing work

procedures, through exploiting the functions in the new database system, and

through revising the IPC thesaurus to evolve with MeSH terms. The development

of a bilingual thesaurus would be helpful to bridge the content.

Management

There are annual reviews of the documentation centre

activities and great strength in a centralized purchasing department and

budget, with centralized IT services and staff training programs consolidating

resources and expertise. However, this also resulted in reduced flexibility and

an increase in the time needed for change. The quality assurance activities are

sporadic and irregular. There is a need to encourage quality assurance

processes to create value.

Marketing

NosoBase® presents multiple channels established over

a significant period with professional learned societies and the French Public

Health Agency. It has been involved regularly in professional conferences and

in the establishment of national guidelines, and has a strong presence on these

websites and professional forums. However, there have been few user

satisfaction surveys, and there is an insufficient use of modern user feedback

channels, such as through social media. Opportunities for growth involve

analyzing modern user needs to better adapt services, and growing its online

presence through European and international IPC channels (e.g., WHO and CDC).

NosoBase® could be marketed towards medical students and non-IPC healthcare

professionals, as well as other francophone countries.

Discussion

Step 1 and Step 2 of this study highlighted the

potential of a specialized or subject-specific bibliographic database providing

literature curated by trained librarians. NosoBase® presented good coverage and

availability of research articles on the theme of hand hygiene. It is practical

and relevant for French users as it contains and regularly updates new French

legislation and guidelines linked to IPC in healthcare, as well as

international IPC guidelines. It carries good representation and scope of

French language health journals in this field, a majority of which are not

indexed internationally or are not on PubMed.

However, Step 3 of this study underlines the need for

more modern approaches in communication and marketing to encourage access by

modern users. NosoBase® needs to adapt its website and database access

accordingly, with better brand presence on social media, and a more

user-friendly approach. NosoBase® has taken positive steps towards this by

transitioning in 2017 to a new FRBR database system, enabling documentation to

be stored according to modern multiple formats such as electronic or

multimedia. Earlier studies have highlighted the need to evolve traditional

librarian services toward point of care (Lamb, Jefferson, & White, 1975;

reviewed by Van Kessell, 2012). NosoBase® needs to examine such approaches in

the future.

This study has limitations. The systematic reviews

were selected based on a date cutoff with very simplified keywords. The search

was limited to a sample size of three systematic reviews and a single theme of

hand hygiene. Qualitative discussions were limited to a select number of

librarians who were closely involved with NosoBase® documentation centres;

information obtained from users of the database and services may have provided

different perspectives.

This is the first quality assurance review of the content of the bibliographic

database NosoBase®. A previous quality assurance review was based on a user

satisfaction survey about the web resources in general (Sanlaville, Angibaud,

Girot, Lebascle, & Yvars, 2011). This study can thus be used as a

foundation for future bibliographic content review. Hand hygiene may be a theme

that naturally interests a wider audience than expected. However, infection

control and prevention is in general a multidisciplinary field and has a wide

target audience. The next steps proposed by this study are to encourage

NosoBase® to include more nursing care journals, and to expand this assessment

by searching and comparing with other systematic reviews on different IPC

themes.

In 2015, a French language based portal, LiSSa, which

stands for Scientific Literature on Health, was created and financed by the national

research agency (ANR), acknowledging “the shared opinion of the National

Academy of Medicine, that [it was necessary in France] to have a bibliographic

database to improve the visibility, access and dynamism of medical and

paramedical literature in French” (Griffon, Scheurs, & Darmoni, 2016, p.

956). It is an encouraging development toward which NosoBase® hopes to

contribute.

Conclusion

Specialized or subject-specific bibliographic

databases came into being due to the growth and proliferation of publications.

However, they currently face increasing costs of maintenance, competition from

free online access to multidisciplinary databases such as PubMed, and the

development of online search engines such as Google Scholar. Evidence based

practices in librarianship also led to the development of methodologies to

evaluate the relevance of documentation centres.

This study explored the relevance of the national IPC

bibliographic database NosoBase® and its documentation centre services. The

results indicate its relevance, reflected by a good coverage and availability

of citations from three systematic reviews based on the theme of hand hygiene,

a wide scope of content based on hand hygiene related keywords, and an

important listing of French language based publications and grey literature.

The qualitative approach through semi-structured discussions with all the

librarians in the various documentation centres provided a framework analysis

of strengths, weaknesses, and opportunities of the documentation centre

services. Due to the ever-changing landscape of information services and

access, documentation centres need to continuously measure the quality of their

contribution, and base their practice on evidence. NosoBase® has a rich

heritage in France in the specialized multidisciplinary field of infection

prevention and control. By adapting to modern user needs and improving

communication and access, NosoBase® will be able to contribute towards evidence

based health practice and evidence based librarianship.

Epilogue: Due to restructuring of national infection

control centres and related budgets, the funding of NosoBase® has been

dramatically reduced in 2019, and its activities will be taken up by a single

different infection control centre, limiting updates mainly to French

legislation and recommendations. Its bibliographic database has been suspended.

The database BDSP faces a similar fate.

References

Aagaard, T., Lund, H., & Juhl,

C. (2016). Optimizing literature search in systematic reviews – are MEDLINE,

EMBASE and CENTRAL enough for identifying effect studies within the area of

musculoskeletal disorders? BMC Medical

Research Methodology 16, 161. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-016-0264-6

Beyer, F. R. & Wright, K. (2013). Can we prioritize which databases

to search? A case study using a systematic review of frozen shoulder

management. Health Information and Libraries Journal, 30(1), 49-58.

https://doi.org/10.1111/hir.12009

Boeker, M., Vach, W., & Motschall, E. (2013). Google Scholar as

replacement for systematic literature searches: Good relative recall and

precision are not enough. BMC Medical

Research Methodology, 13, 131. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-13-131

Booth, A. & Brice, A. (2004). Evidence-based

practice for information professionals: A handbook. London, United Kingdom:

Facet Publishing.

Bramer, W. M., Giustini, D., Kramer, B. M. R., & Anderson, P. F. (2013).

The comparative recall of Google Scholar versus PubMed in identical searches

for biomedical systematic reviews: A review of searches used in systematic

reviews. Systematic Reviews, 2(115). https://doi.org/10.1186/2046-4053-2-115

Brettle, A. J. & Long, A. F. (2001). Comparison of bibliographic

databases for information on the rehabilitation of people with severe mental

illness. Bulletin of the Medical Library

Association, 89(4), 353-362. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC57964/

Brettle, A., Maden-Jenkins, M., Anderson, L., McNally, R., Pratchett,

T., Tancock, J., Thornton, D., & Webb, A. (2011). Evaluating clinical

librarian services: A systematic review. Health

Information and Libraries Journal, 28(1), 3-22. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-1842.2010.00925.x

Canadian Association of Research Libraries (2010). Core Competencies for 21st Century CARL Librarians.

Ottawa, ON: Author. Retrieved from https://www.carl-abrc.ca/doc/core_comp_profile-e.pdf

Centre for Reviews and Dissemination. (2009). Systematic reviews: CRD’s guidance for undertaking reviews in health

care. York, United Kingdom: University of York. Retrieved from https://www.york.ac.uk/media/crd/Systematic_Reviews.pdf

Dufour, J.-C., Mancini, J., & Fieschi, M. (2009). Recherche de données

factuelles [Searching for evidence-based data]. Journal de Chirurgie 146(4), 355-367.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jchir.2009.08.025

Gasparyan, A. Y., Yessirkepov, M., Voronov, A. A., Trukhachev, V. I.,

Kostyukova, E. I., Gerasimov, A. N., & Kitas, G. D. (2016). Specialist

bibliographic databases. Journal of

Korean Medical Science, 31(5), 660-673.

https://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2016.31.5.660

Gehanno, J-F., Rollin,

L., & Darmoni, S. (2013). Is the coverage of Google Scholar enough to be

used alone for systematic reviews? BMC

Medical Informatics and Decision Making, 13(7). https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6947-13-7

Glasziou, P. & Aronson, J. K. (2017). A brief history of clinical

evidence updates and bibliographic databases. JLL Bulletin: Commentaries on the History of Treatment Evaluation.

Retrieved from http://www.jameslindlibrary.org/articles/brief-history-clinical-evidence-updates-bibliographic-databases/

Goodman, K. W. (2002). Ethics and

Evidence-based Medicine: Fallibility and Responsibility in Clinical Science. Cambridge,

United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press.

Griffon, N.,

Schuers, M., & Darmoni, S. J. (2016). Littérature Scientifique en Santé (LiSSa): Une alternative à l’anglais? [LiSSa: An alternative in French to browse health scientific

literature?]. La Presse Médicale, 45(11), 955-956. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lpm.2016.11.001

Guistini, D. & Kamel Boulous, M. N. (2013). Google Scholar is not enough to be used alone for systematic reviews. Online Journal of Public Health Informatics,

5(2), 214. http://doi.org/10.5210/ojphi.v5i2.4623

Haddaway, N. R., Collins, A. M., Coughlin, D., & Kirk, S. (2015).

The role of Google Scholar in evidence reviews and its applicability to grey

literature searching. PLoS ONE 10(9),

e0138237. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0138237

Jamali, H. R. & Asadi, S. (2010). Google and the scholar: The role

of Google in scientists' information‐seeking behaviour. Online Information Review, 34(2), 282-294. https://doi.org/10.1108/14684521011036990

Palisse, V. (2011). Valoriser les

produits documentaires: Quelles méthodes, quel plan d’action? (Mémoire). Retrieved from https://memsic.ccsd.cnrs.fr/mem_00679869/document

Rathbone, J., Carter, M., Hoffmann, T., & Glasziou, P. (2016). A

comparison of the performance of seven key bibliographic databases in

identifying all relevant systematic reviews of interventions for hypertension. Systematic Reviews, 5(27). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-016-0197-5

Rethlefsen, M. L., Murad, M. H., & Livingston, E. H. (2014).

Engaging medical librarians to improve the quality of review articles. JAMA 312(10), 999-1000. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2014.9263

Rethlefsen, M. L., Farrell, A. M., Osterhaus Trzasko, L. C., &

Brigham, T. J. (2015). Librarian co-authors correlated with higher quality

reported search strategies in general internal medicine systematic reviews. Journal of Clinical

Epidemiology, 68(6), 617-626. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2014.11.025

Sanlaville, N., Angibaud, M., Girot, I., Lebascle, K., & Yvars, S.

(2011). Résultats de l’enquête de satisfaction NosoBase. Unpublished report.

Savey, A., Sanlaville, N., & Fabry, J. (2000). De la documentation

à la communication: L’expérience de NosoBase®. [From documentation to

communication: Experiences from NosoBase®]. Techniques

Hospitalières, 651, 39-42.

Toneatti, V. (2008). Valoriser un

centre de documentation par une démarche qualité. (Mémoire). Retrieved from http://bdid-intd.cnam.fr/memoires/2008/TONEATTI.pdf

Van Kessel, K. (2012). Gertrude Lamb’s pioneering concept of the

clinical medical librarian. Evidence

Based Library and Information Practice, 7(1), 125-128. https://doi.org/10.18438/B8NS5G