Research Article

The Library Assessment

Capability Maturity Model: A Means of Optimizing How Libraries Measure

Effectiveness

Simon Hart

Policy, Planning and

Evaluation Librarian

University of Otago Library

Dunedin, New Zealand

Email: simon.hart@otago.ac.nz

Howard Amos

University Librarian

University of Otago Library

Dunedin, New Zealand

Email: howard.amos@otago.ac.nz

Received: 19 July 2018 Accepted: 11 Oct. 2018

![]() 2018 Hart and

Amos.

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative

Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

2018 Hart and

Amos.

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative

Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

DOI: 10.18438/eblip29471

Abstract

Objective

–

This paper presents a Library Assessment Capability Maturity Model (LACMM) that

can assist library managers to improve assessment. The

process of developing the LACMM is detailed to provide an evidence trail to

foster confidence in its utility and value.

Methods

–

The LACMM was developed during a series of library benchmarking activities

across an international network of universities. The utility and value of the LACMM was tested by the benchmarking

libraries and other practitioners; feedback from this testing was applied to

improve it. Guidance

was taken from a procedures model for developing maturity models that draws on

design science research methodology where an iterative and reflective approach

is taken.

Results –

The activities decision making junctures and the LACMM as an artifact make up

the results of this research. The LACMM

has five levels. Each level represents a measure of the effectiveness of any

assessment process or program, from ad-hoc processes to mature and continuously

improving processes. At each level there are criteria and characteristics that

need to be fulfilled in order to reach a particular maturity level.

Corresponding to each level of maturity, four stages of the assessment cycle

were identified as further elements of the LACMM template. These included (1) Objectives, (2) Methods and data collection, (3) Analysis and interpretation, and (4) Use of results. Several attempts were needed to determine the

criteria for each maturity level corresponding to the stages of the assessment

cycle. Three versions of the LACMM were developed to introduce managers to

using it. Each version corresponded to a different kind of assessment activity:

data, discussion, and comparison. A generic version was developed for those who

have become more familiar with using it. Through a process of review,

capability maturity levels can be identified for each stage in the assessment

cycle; so too can plans to improve processes toward continuous improvement.

Conclusion – The LACMM will add to the plethora of resources

already available. However, it is hoped that the simplicity of the tool as a

means of assessing assessment and identifying an improvement path will be its

strength. It can act as a quick aide-mémoire or form the basis of a

comprehensive self-review or an inter-institutional benchmarking project. It is

expected that the tool will be adapted and improved upon as library managers

apply it.

Introduction

The improvement of processes has become

increasingly important in libraries, especially within the higher education

context. This has been in response to wider economic pressures that have seen

limited budgets and the rise of accountability (Lilburn, 2017). Libraries have prioritized

the need to demonstrate a return on investment, show that users’ needs are

being met, remain relevant, offer (added) value, and align with wider strategic

imperatives (Matthews, 2015; Oakleaf, 2010; Sputore & Fitzgibbons, 2017; Tenopir,

Mays & Kaufman, 2010; Urquhart & Tbaishat,

2016). A drive for efficiency and effectiveness has culminated in calls to

foster cultures of quality, assessment, and evidence based decision-making (Atikinson, 2017; Crumley & Koufogiannakis, 2002; Lakos &

Phipps, 2004). Business as usual is no longer enough. Doing more with less

while continuing to improve is the new norm. Applying assessment processes and

improving upon them has become imperative for library mangers (Hiller, Kyrillidou, & Oakleaf, 2014).

The challenge is how can assessment be conducted and improved efficiently and

effectively. This paper documents the development of a tool—the Library Assessment Capability Maturity Model

(LACMM)—that can meet this need.

Literature Review

The

issue of library assessment is well documented (Heath, 2011; Hufford, 2013;

Town & Stein, 2015). Signposts, “how to” manuals, and examples of practice

are readily available (Oakleaf, 2010; Wright &

White, 2007). A range of comprehensive books have been published (Appleton,

2017; Brophy, 2006; Heron, Dugan, & Nitecki, 2011; Matthews, 2015).

The

tools to measure effectiveness are continually evolving—from the questionnaire

employed by the Advisory Board on College Libraries across Carnegie libraries

in the 1930s (Randel, 1932) to Orr’s framework for quantitative measure for

assessing the goodness of library services (Orr, 1973) to more contemporary

tools like LibQual+® surveys (Association of Research

Libraries, 2012) and web based assessment tools offered by Counting Opinions (n.d.). Significant investment has been made to strengthen

librarians’ assessment practices, for example through the ACRL program Assessment in Action: Academic Libraries and

Student Success (Hinchliffe & Malenfant,

2013). Work has been undertaken to identify factors important to effective

library assessment (Hiller, Kyrillidou, & Self,

2008) as well as to identify factors influencing an assessment culture (Farkas, Hinchliffe, & Houk,

2015). In discussing the history of library assessment, Heath (2011) noted that

“recent years have seen a collaborative culture of assessment reach its full

maturity” (p. 14).

Despite

the rich literature that exists on assessment practices, the concept of

maturity in assessment has only received limited attention in libraries. Cosby

(1979) popularized the concept of maturity of business processes by considering

them in stages building on each other, offering an effective and efficient

means for the analysis and measurement of the extent to which a process is

defined, managed, assessed, and controlled. The application of capability

maturity within a framework emerged out of the software engineering industry

where Paulk, Curtis, Chrissis, and Weber (1993)

conceived a Capability Maturity Model (CMM). Subsequently, CMMs have been

applied in a range of other industries and organizations to assess the level of

capability and maturity of critical processes, such as project management

capability (Crawford, 2006), people capability (Curtis, 2009), and contract

management process capability (Rendon, 2009).

A

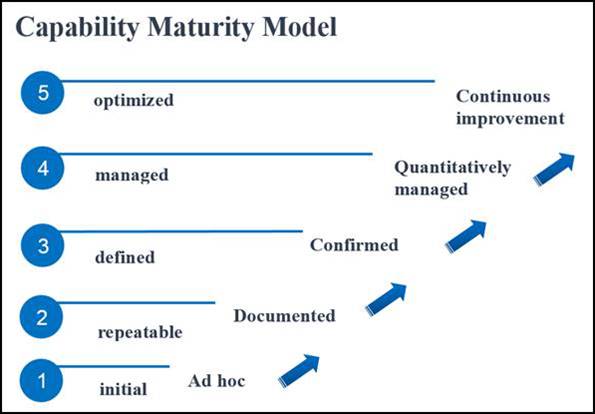

CMM has five levels of capability maturity, as illustrated in Figure 1 (adapted

from Paulk, Curtis, Chrissis, & Weber, 1993).

Each level represents a measure of the effectiveness of any specific process or

program, from ad-hoc immature processes to disciplined, mature, and

continuously improving processes. The CMM provides criteria and characteristics

that need to be fulfilled in order to reach a particular maturity level. Actual

activities are compared with the details at each level to see what level these

best align to. Consideration of the details in the levels above where

activities align provide guidance on where improvement can be made (Becker, Knackstedt, & Pöppelbuß,

2009).

The first reported instance of the CMM being

utilized in developing a maturity model in a library setting was by Wilson and

Town (2006). Here the CMM was used as a reference model to develop a framework

for measuring the culture of quality within an organization. As part of her

doctoral research, Wilson (2013) went on to develop a comprehensive

and useful Quality Maturity Model (QMM) and Quality Culture Assessment

Instrument for libraries (www.qualitymaturitymodel.org.uk).

Subsequently the CMM has been used to develop maturity models in library

settings to map knowledge management maturity (Mu 2012; Yang 2009, 2016) and

digital library maturity (Sheokhshoaei, 2018). Only

Wilson (2013) and Sheokhshoaei (2018) provided a

detailed account of how their model was developed.

There

are other instances of developing maturity models in a library setting. Gkinni (2014) developed a preservation policy maturity

model; however, this used a maturity assessment model promoted by de Bruin and Rosemann (2005). Howlett (2018)

has announced a project to develop an evidence based maturity model for

Australian academic libraries. It will describe characteristics of evidence

based practice and identify what library mangers can implement to progress

maturity at a whole organization level. At this stage, it is not known whether

this will follow the structure of the CMM.

Figure

1

Capability

maturity model.

There

are limited instances of the application of CMMs within the library literature.

An early version of the QMM was applied by Tang (2012) in benchmarking quality

assurance practices of university libraries in the Australian Technology

Network. Egberongbe and Willett (2017) refer to an

assessment of quality maturity level in Nigerian university libraries that

applied the Prince 2 Maturity Model from the field of project management.

Similarly, within a university library in Sri Lanka, Wijetunge

(2012) reported using a version of a knowledge management maturity model;

however, like Willett (2017), this also did not apply a CMM in its development.

Aims

This paper shares the LACMM, a tool that can assist

library mangers with improving assessment. The LACMM offers managers an

effective tool where, through a process of self-review, assessment processes

can be simplified and considered in a stage-by-stage manner along an

anticipated, desired, and logical path to identify how well developed and

robust processes actually are. It offers efficiency as it acts as a diagnostic

tool that helps to identify a course of action to optimize performance. The

process of developing this tool is presented with an evidence trail to foster

confidence in its utility and value.

Methods

The LACMM was developed during a series of library

benchmarking activities across a group of seven universities from across the

world, the Matariki network (https://matarikinetwork.org/).

The authors of this paper coordinated the development of the LACMM and managed

the benchmarking activities. One author is a library director (H.A.) and the

other (S.H.) has assessment responsibilities as a significant component of his

role. The network libraries shared in the development of the LACMM as they

addressed the following question: If we enable and support the academic

endeavour, how do we measure our effectiveness? Guidance was taken from Becker,

Knackstedt, and Pöppelbuß

(2009), who offered a procedures model for developing maturity models that

draws on design science research methodology (Hevner,

2004). This provided a clear flow of activities and decision-making junctures,

emphasising an iterative and reflective approach.

The benchmarking activities included structured

case studies from each of the university libraries that were assessed and best

practice examples and resources that were shared. Decisions were made through

consultation via shared discussion documents. These conversations occurred

during three day-long annual meetings between 2013 and 2017 when the seven

library directors met as part of a series of Matariki

Humanities Colloquia that had emerged as part of the network activities. Prior

to each meeting staff from the libraries responded to a series of questions

with reference to their library’s case study. The responses were shared via an

online collaborative workspace. Using the workspace allowed each library to

come to the activity as resources allowed. Each case study could be reviewed

prior to the meeting where more questions could be answered and each library

could report on what they learned from considering each other’s best practice

examples. This process ensured a rich and productive interaction during the

meetings (Hart & Amos, 2014).

Benchmarking topics focused on activities and

practices for library programs that supported teaching, research, and the

student experience. Aligned to wider strategic priorities, the topics included

transition of first year students to university life, library space that

support students’ experiences, planning for change to support research, how the

library helps researchers measure impact, and the cost

and contribution to the scholarly supply chain. As the library directors

considered possible areas of improvement, the need to improve assessment

processes was acknowledged. Early on in the benchmarking process, the library

directors agreed to investigate, as a separate but aligned activity, the use of

a CMM for

library assessment as a shared response to address “how we measure our

effectiveness” (Hart & Amos, 2014, p. 59).

To encourage wide application of the tool, the

authors promote the use of terms “assessment” and “evaluation” as

interchangeable within the library context. While some argue for a distinction

between assessment and evaluation (Hernon &

Dugan, 2009) it needs to be recognized that this call is made within the

context of higher education, where historically care has been taken to

differentiate between assessing learners and evaluating things or objects (Hodnett, 2001). In contrast, Hufford (2013) concedes that

among librarians the use of each term is ambiguous, and their uses have changed

over time.

Results

Problem Definition

The idea of developing a guide or roadmap that a CMM

could offer appealed to the library directors within the network. They

acknowledged that there were plenty of good case studies, resources, and lists

of what had to be in place to advance a culture of assessment. For example, see

bibliographies by Hufford (2013) and Poll (2016). While these are useful to

learn about what others are doing, they did not offer systematic guidance on

how to improve assessment processes within current and planned activities and

programmes. It was confirmed that testing the model across a group of

international libraries would strengthen its application to a wider audience

(Maier, Moultrie & Clarkson, 2012; Wendler,

2012).

Applying the CMM to library assessment was further

validated when one of the partner libraries shared their experience using the

revised Australasian Council on Online, Distance and e-Learning (ACODE)

benchmarking tool, which focuses on technology-enhanced learning (McNaught, Lam, & Kwok, 2012; Sankey, 2014a). The ACODE

tool includes eight benchmarks with each containing a series of criteria-based

performance indicators using a 1 to 5 scale of capability. It comprises a

two-phased application, where it is applied in a self-assessment process and

then used to develop a team response within or between institutions (Sankey,

2014b). This example was useful as it allowed the library directors to

conceptualize what a LACMM may look like and how it may be utilized. It was

recognized that through the benchmarking activities the library directors could

review their assessment processes against criteria, compare with what others

had done, and draw upon this to improve practices.

Comparison with Existing Models

Having defined the problem and agreed upon an

approach, the next stage of the procedures model required comparison with

existing models. Here Wilson’s (2013) comprehensive QMM was considered. The QMM included 40

elements grouped into 8 facets. Those elements that focussed on assessment

processes included progress monitoring, performance measurement, gathering

feedback, collation of feedback, responding to feedback, and acting on

feedback. Despite this focus, the QMM was rejected

for this activity because of its complexity and size. The aim was to provide an

efficient tool that would not overwhelm those using it. It was also rejected

because overall the facets did not provide direct alignment to library

assessment. Instead, it focused on the broader concept of quality of which

assessment is a smaller part. It was noted that, when it came to assessment,

the QMM tended to focus more on feedback and not on assessment as a process. As

noted earlier, with no other suitable model dealing with the issue of library

assessment available, the need to develop a distinctive LACMM was confirmed.

Iterative

Model Development

To

provide guidance in determining the characteristics of a LACMM, the literature

on library assessment was reviewed. Bakkalbasi, Sundre, and Fulcher’s (2012) work on assessing assessment

was considered. In presenting a toolkit to evaluate the quality and rigor of

library assessment plans, their work draws on the elements of the assessment

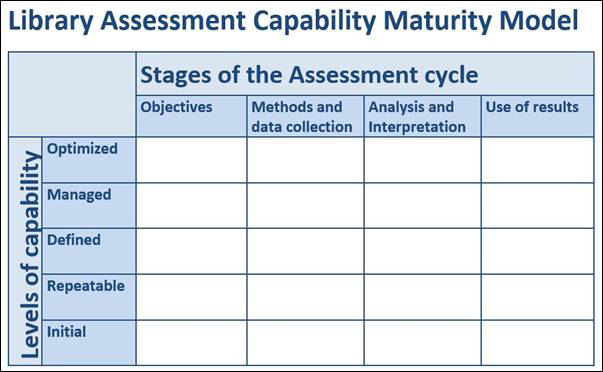

cycle. The elements include (1) establishing assessment objectives, (2)

selecting and designing methodologies and collecting data, (3) analyzing and

interpreting data, and (4) using the results. It was decided that focusing on

these elements would reduce the complexity of the design and simplify the

development of the LACMM. A template of the LACMM was determined, as

illustrated in Figure 2.

The LACMM template was shared with library managers

and assessment practitioners at international forums. Presentations were made

at the 11th Northumbria International Conference on Performance

Measurement in Libraries and Information Services 2015, the OCLC 7th

Asia Pacific Regional Council Conference 2015, and the Council of Australian

University Librarians Forum: Demonstrating and Measuring Value and Impact 2016.

During the discussions at these presentations, attendees confirmed the utility,

value, and simplicity of the model (Amos & Hart, 2015; Hart, 2016; Hart

& Amos, 2015).

As part of the shared development of the LACMM,

each library in the Matariki network was invited to

populate the model as an additional part of a benchmarking activity. They were

asked to consider the assessment applied in the case study they were reporting

on in the benchmarking activity, to rank the level of capability for each stage

of assessment in the project, and then to provide notes of the criteria for

each of these. When only three of the seven libraries completed this task with

varying degrees of success, the project lead decided to change tack to get more

buy in. The decision was made, in line with the iterative nature of the

procedures model, that a group of library staff at the University of Otago

would draft criteria for the network libraries to consider in the next

benchmarking activity.

Figure

2

Library

assessment capability maturity model template.

The Otago staff selected for this task all had

experience in either business management and or assessment roles. They included

the University Librarian, the Resources Assessment Librarian, the Library

Programmes Manager, and the Policy Planning and Evaluation Librarian. Drawing

on their practice and knowledge, these staff met several times to discuss,

develop, and revise criteria. Following this, a draft version was then tested

with the staff at Otago who were responsible for undertaking the next

benchmarking activity.

In reviewing the version completed by Otago staff

as part of the benchmarking activity, the project lead noted that a number of

different kinds of assessment activities had been documented. Furthermore, the

different types of activities were reported on in the different assessment

stages of the LACMM. For example, survey data were covered in objectives,

methods, and results, while group interviews were reported on in analysis.

Reflecting on this, the project lead decided to use the Otago criteria group to

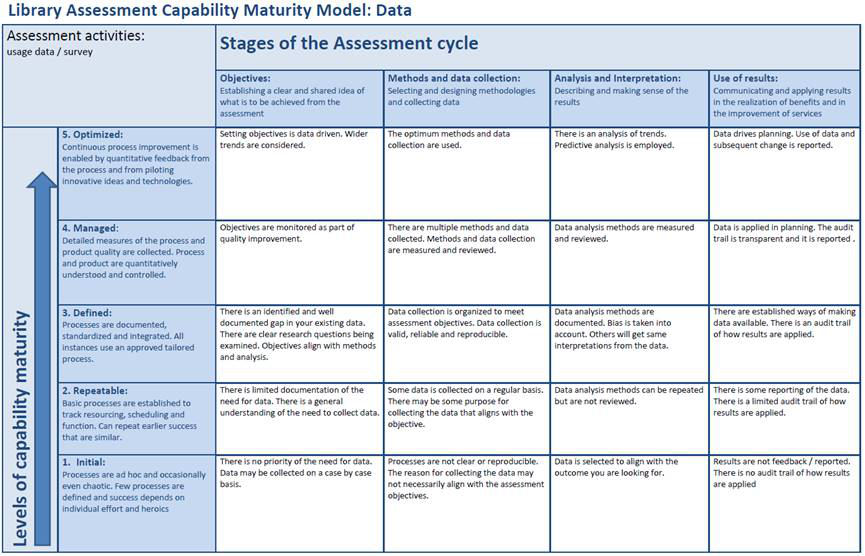

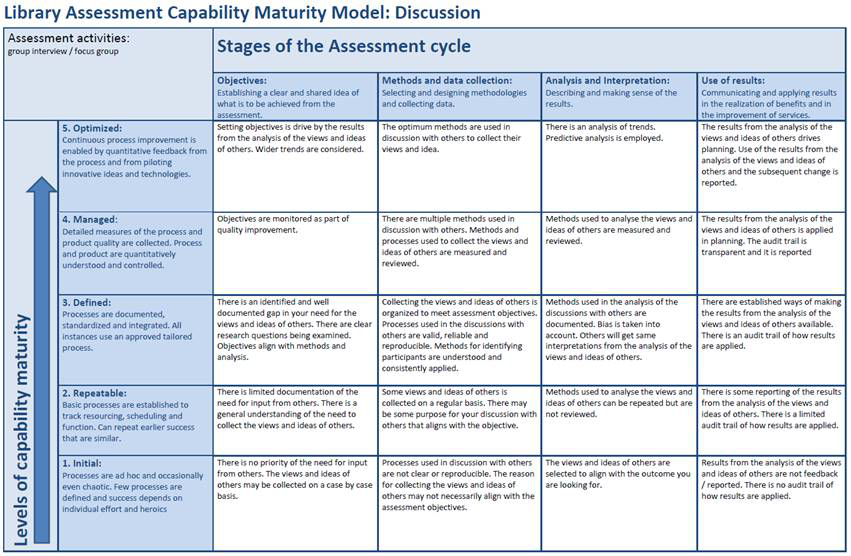

produce three versions of the model for different types of assessment

activities. The wording of the criteria in each corresponded to the particular

assessment activity:

1.

Data, to cover assessment activities that included

usage data and surveys

2.

Discussion, to cover assessment activities that

included group interviews and focus groups

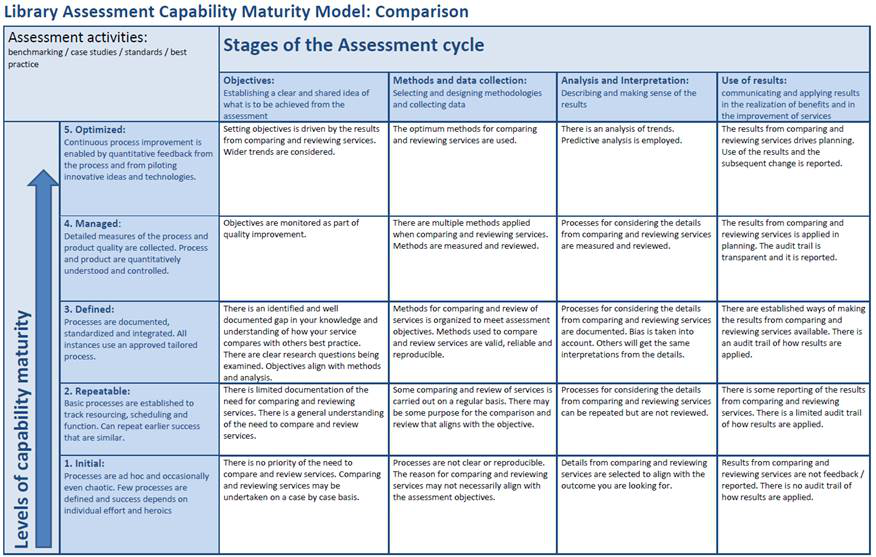

3.

Comparison, to cover assessment activities that

included benchmarking, case studies, standards, or best practice examples

To add more clarity, descriptions were provided for

each of the levels of capability maturity and the stages of the assessment

cycle (see Figures 3, 4, and 5). These three versions were then distributed to

the Matariki Libraries as part of the next

benchmarking activity.

Testing the Model

Distributing three versions of the LACMM, including

specific criteria for each, proved a successful strategy with six of the seven

libraries completing them. The library that did not submit indicated that the

project they reported on did not lend itself to assessment activities. Overall,

four libraries reported on one type of assessment activity that was applied in

the project, and two libraries reported on two types of activities. Each

library ranked their capacity maturity across each of the four stages of the

assessment cycle, providing evidence about how they met the criteria.

Applying the model provided each library the

opportunity to review their performance and see where they could improve.

Following this, each of the libraries’ responses were shared among one another

and then discussed at a face-to-face meeting. This meeting provided the

opportunity to clarify any issues and seek more tacit information from each

other on assessment processes and resources—in particular, from those who scored a higher level

of capability maturity.

At the meeting, feedback on the criteria and

templates for different assessment processes in the LACMM were received and

then confirmed. Feedback primarily focused on the wording used. Fine tuning

terminology across a group of international libraries helped to provide wider

appeal and utility. The library directors agreed that having a template for

different kinds of assessment activities assisted their staff to complete the

model in the first instance. However, as their staff become familiar with using

the LACMM, the directors agreed that using one generic version for any type of

assessment activity would be sufficient. The directors confirmed the usefulness

of the tool and decided that they had sufficiently addressed the question of

how they measure their effectiveness. Having built a structure and precedence

for collaborating and sharing resources through the benchmarking activities,

the directors agreed to refocus on other projects that support scholarly

communications and digitizing collections. Nevertheless, most committed to

applying the LACMM in projects at a local level. Two directors commented that

it was hard to get their staff interested in participating in benchmarking.

However, it was acknowledged that within the activities each partner had the

flexibility to come to the benchmarking as resources allowed. As Town (2000)

asserts, “benchmarking is as much a state of mind as a tool; it requires

curiosity, readiness to copy and a collaborative mentality” (p. 164).

In line with the procedure model, further testing

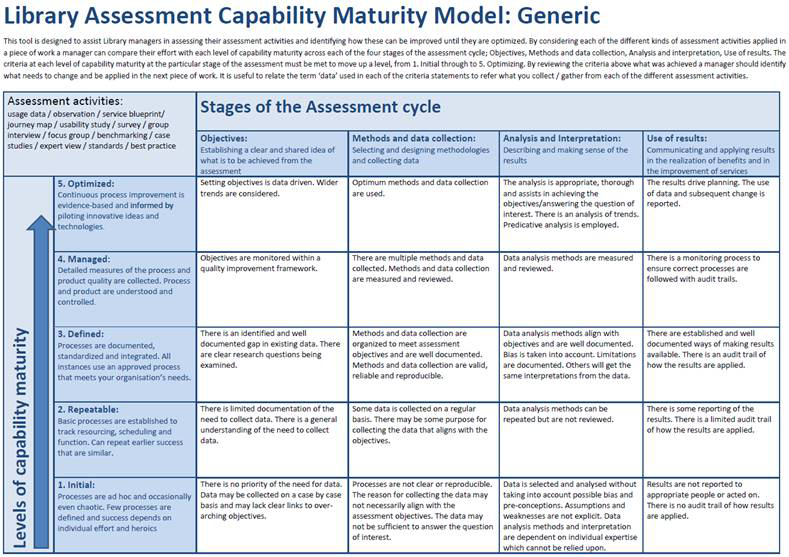

of the generic LACMM was carried out when it was shared with the Council of

Australian University Librarians Value and Impact Group. The group acts as a

community of practice with practitioners from New Zealand and Australian

university libraries with a quality or communication role. Overall the

practitioners confirmed its utility and value. They suggested including more

examples in the assessment activities and that brief “how to” instructions be

included. The generic version that resulted from this testing is shown in

Figure 6. When advancing to using the generic LACMM, it is useful to understand

that the term “data” used in each of the criteria statements refers to “what is

collected from each of the different assessment activities.”

Figure

3

Library

assessment capability maturity model for data.

Figure

4

Library

assessment capability maturity model for discussion.

Figure

5

Library

assessment capability maturity model for comparison.

Figure

6

Library

assessment capability maturity model generic version.

Discussion

Put simply, the LACMM is designed to assist library

managers in assessing their assessment activities and in identifying how these

can be improved until they are optimized through continuous improvement. In the

first application of the LACMM, there is benefit in using a recent piece of

work or an example that is considered leading practice. Managers can choose a

piece of work that included assessment activities or that was an assessment

activity. For example, the assessment activity could be something that was

carried out to inform an initiative or to review the effectiveness of an

initiative.

Once a piece of work has been selected, the next

step is to identify the kinds of assessment activities that were applied in

terms of data, discussion, or comparison (see Figures 3, 4, and 5). Then, for

each kind of assessment activity, managers should make notes on what was

carried out at each stage of the assessment cycle, including Objectives, Methods and data collection, Analysis

and interpretation, and Use of

results. These notes should then be compared with the criteria listed at

each level of capability maturity from the Initial

level upwards to the Optimized level

for each of the stages of the assessment cycle. All of the criteria at a

particular level must be met for that level to be attained. This comparison

should be carried out for each kind of assessment activity applied in the piece

of work.

When

managers are familiar with using the LACMM for the different kinds of

assessment activities, they can then move to using the generic model. Here it

is useful to understand that the term “data” refers to “what is collected for

each of the different assessment activities.”

When

comparing a piece of work, managers may identify that the first three elements

of the assessment cycle meet the criteria for the Defined level because the assessment processes in the piece of work

are documented, standardized, and integrated. However, when it comes to the Use of results, what was carried out may

only meet the criteria for the Repeatable

level. For example, the piece of work may have inconsistent reporting with no

audit trail of how results are applied. For guidance on improving this element,

a manager can review the criteria in the Capability

level and apply those criteria in the next project. In addition, managers,

especially those who attain projects with higher levels of capability, could

share their experiences of using the LACMM and the processes and resources they

applied.

Having

applied the LACMM to a representative range of assessment activities, a manager

can characterize their whole assessment program. This may be a useful exercise

to help set targets for improving capability across the library or for

benchmarking. However, as was seen through testing the LACMM, comparing

examples of leading practice where tangible examples could be shared was also

beneficial.

The LACMM has advantages over other tools and

processes available. In only considering the four stages of the assessment

cycle, the LACMM is not as complex as Wilson’s (2013) QMM, which includes 40

elements grouped into 8 facets. By focusing on assessment processes in a

stage-by-stage manner, self-review is simplified. The LACMM offers efficiency

as both a self-review tool and as a means of identifying improvements. Although

this tool will add to the plethora of resources already available (see Farkas,

Hinchliffe, and Houk, 2015 and Hiller, Kyrillidou, and Self, 2008), the simplicity of the tool as a means of assessing assessment and

identifying an improvement path is its strength. It can act as a quick

aide-mémoire and form the basis of a comprehensive self-review or an

inter-institutional benchmarking project (Sankey, 2014b).

The benchmarking exercises provided a unique

opportunity to develop the LACMM where it could be applied and tested against

actual case studies of best practice across an international group of

university libraries. The development utilized staff experience at different

levels of the organization, including both practitioners and leaders. The

results at decision-making junctures were verified at international forums of

library managers and assessment practitioners. Drawing on design-science

research methodology (Hevner, 2004) was also

beneficial. The iterative approach allowed methods to be trialled and revised

as required. The schedule of annual meetings with each benchmarking exercise

stretched over a year provided ample time for reflection in the shared

development of the LACMM as a useful artifact. Being flexible with timeframes

allowed each partner to come to the exercise as resources allowed (Hart &

Amos, 2014). The successful use of the design science research methodology

demonstrates the potential of this approach to other library and information

practitioners.

Several limitations to the LACMM and its

development must be acknowledged. First, the LACMM is sequential in nature and

represents a hierarchical progression. Some may argue that real life is not

like that. Some may legitimately be content to be at a certain level and not

prioritize resourcing to improve practice. Second, the authors acknowledge that

bias may have influenced the development of the LACMM because it became the

only means for participating libraries to respond to the question of how they

measure their effectiveness. However, when deciding this path, no other options

were put forward by other network partners. Third, limitations exist because

the LACMM was developed solely within the context of university libraries.

Input from other areas within the wider library and information management

sector would provide additional insight into the relevance and usefulness of

the LACMM.

The LACMM does not replace the comprehensive and

useful QMM as a means of assessing the quality of library quality (Wilson,

2015). It does, however, provide an effective and efficient means of assessing

library assessment.

Conclusion

The LACMM is an effective tool that, through

self-review assessment processes, can be simplified and considered in a

stage-by-stage manner along an anticipated, desired, and logical path to

identify how mature assessment processes actually are. Managers can compare

their effort with each level of capability maturity from the Initial level through to the Optimized level across each of the four

stages of the assessment cycle (Objectives,

Methods and data collection, Analysis and interpretation, and Use of results. The LACMM offers

efficiency as it acts as a diagnostic tool that helps identify a course of

action to improve performance. Criteria at each level of capability maturity at

the particular stage of the assessment must be met to move up a level. The

level above a particular stage provides guidance on how assessment process can

be improved.

It is anticipated that providing the evidence trail

of the development of the LACMM will further foster confidence in its utility

and value. It is expected that the tool will be adapted and improved upon as library

managers apply it. As this resource is being shared with a Creative Commons

Attribution–NonCommercial–ShareAlike

license, it will support other practitioners in sharing their work with and

improving the LACMM as a means of optimizing how libraries measure their

effectiveness.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the

contributions of their colleagues at the University of Otago Library, those

across the Matariki Network of Universities, and

others that participated in various forums in the shared development the LACMM.

Naku te

rourou nau te rourou ka

ora ai te

iwi.

References

Amos, H., &

Hart S. (2015). From collaboration to

convergence: A breakthrough story from an international network of Libraries.

Paper presented at OCLC 7th Asia Pacific Regional Council Conference.

Melbourne, Australia.

Appleton, L.

(2017). Libraries and key performance

indicators: A framework for practitioners. Kidlington, England: Chandos.

Association of

Research Libraries. (2012). LibQual+, charting

library service quality. Washington, DC: Association of Research Libraries.

Retrieved December 12, 2013 from https://www.libqual.org/documents/admin/Charting

Library Service Quality.ppt

Atkinson, J.

(2017). Academic libraries and quality: An analysis and evaluation framework. New

Review of Academic Librarianship, 23(4), 421-441. https://doi.org/10.1080/13614533.2017.1316749

Bakkalbasi, N.,

Sundre, D. L., & Fulcher, K. F. (2012). Assessing

assessment: A framework to evaluate assessment practices and progress for

library collections and services. In S. Hiller, M. Kyrillidou,

A. Pappalardo, J. Self, and A. Yeager. (Eds.), Proceedings of the 2012 Library Assessment

Conference (pp. 533-537). Charlottesville, VA: Association of Research

Libraries.

Becker, J., Knackstedt, R., & Pöppelbuß,

D. W. I. J. (2009). Developing maturity models for IT management. Business & Information Systems

Engineering, 1(3), 213-222.

Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1007/s12599-009-0044-5

Brophy, P.

(2006). Measuring library performance.

London, England: Facet.

Counting Opinions.

(n.d.). About

us [online]. Retrieved December 12,

2013 from www.countingopinions.com

Crawford, J. K.

(2006). The project management maturity model. Information Systems Management, 23(4),

50-58. https://doi.org/10.1201/1078.10580530/46352.23.4.20060901/95113.7

Crosby, P. B.

(1979). Quality is free. New York:

McGraw-Hill.

Crumley, E.,

& Koufogiannakis, D. (2002). Developing evidence‐based librarianship: Practical

steps for implementation. Health

Information & Libraries Journal, 19(2), 61-70. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1471-1842.2002.00372.x

Curtis, B.,

Hefley, B., & Miller, S. (2009). People

Capability Maturity Model (P-CMM) Version 2.0 (No. CMU/SEI-2009-TR-003). Pittsburgh PA: Carnegie-Mellon University, Software Engineering Institute.

Retrieved from http://www.dtic.mil/dtic/tr/fulltext/u2/a512354.pdf

De Bruin T.

& Rosemann, M. (2005). Understanding the main phases of developing a maturity assessment

model. Paper presented at the 16th Australasian conference on information

systems maturity assessment model. Sydney, Australia. Retrieved from http://eprints.qut.edu.au/25152/

Egberongbe, H.,

Sen, B., & Willett, P. (2017). The assessment of quality maturity levels in

Nigerian university libraries. Library

Review, 66(6/7), 399-414. https://doi.org/10.1108/LR-06-2017-0056

Farkas,

M.G., Hinchliffe, L.J., & Houk, A.H. (2015).

Bridges and barriers: Factors influencing a culture of assessment in academic

libraries. College & Research

Libraries, 76(2), 150-169. https://doi.org/10.5860/crl.76.2.150

Gkinni, Z.

(2014). A preservation policy maturity model: A practical tool for Greek libraries

and archives. Journal of the Institute of

Conservation, 37(1), 55-64. https://doi.org/10.1080/19455224.2013.873729

Hart, S., &

Amos, H. (2014). The development of performance measures through an activity

based benchmarking project across an international network of academic

libraries. Performance Measurement and

Metrics, 15 (1/2), 58-66. https://doi.org/10.1108/PMM-03-2014-0010

Hart, S., &

Amos, H. (2015). Building on what works:

Towards a library assessment capability maturity model. Paper presented at

11th Northumbria International Conference on Performance Measurement in

Libraries and Information Services, Edinburgh, Scotland.

Hart, S.,

(2016). Evaluating library assessment

capabilities: A measure of effectiveness. Paper presented at CAUL Forum:

Demonstrating and Measuring Value and Impact. Sydney, Australia. Retrieved from

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vniexdbsXls

Heath, F.

(2011). Library assessment: The way we have grown. Library Quarterly, 8(11), 7-25.

https://doi.org/10.1086/657448

Hernon, P.,

& Dugan, R. E. (2009). Assessment and evaluation: What do the terms really

mean? College & Research Libraries

News, 70(3), 146-149. https://doi.org/10.5860/crln.70.3.8143

Hernon, P.,

Dugan, R. E., & Nitecki, D. A. (2011). Engaging in evaluation and assessment

research. Santa Barbara, CA: Libraries Unlimited.

Hevner,

A.R., March, S. T., Park, J., & Ram, S. (2004). Design science in

information systems research. MIS

Quarterly, 28(1), 75-105.

https://doi.org/10.2307/25148625

Hiller, S., Kyrillidou, M., & Oakleaf, M.

(2014). The Library assessment conference-past, present, and near future! Journal of Academic Librarianship, 40(3-4),

410-412. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2014.05.013

Hiller, S., Kyrillidou, M., & Self, J. (2008). When the evidence is

not enough: Organizational factors that influence effective and successful

library assessment. Performance

Measurement and Metrics, 9(3), 223-230. https://doi.org/10.1108/14678040810928444

Hinchliffe, L.,

& Malenfant, K. (2013, December 9). Assessment in action program open online

forum [Webcast]. Chicago, IL: Association of College and Research

Libraries. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0G0UQxj6CUM&feature=youtu.be

Hodnett, F.

(2001). Evaluation vs assessment. Las

Cruces, NM: New Mexico State University.

Howlett, A.

(2018). Time to move EBLIP forward with an organizational lens. Evidence Based Library and Information

Practice, 13(3), 74-80. https://doi.org/10.18438/eblip29491

Hufford, J. R.

(2013). A review of the literature on assessment in academic and research

libraries, 2005 to August 2011. portal:

Libraries and the Academy, 13(1),

5-35. https://doi.org/10.1353/pla.2013.0005

Lakos, A., & Phipps, S. (2004). Creating a culture of assessment: A

catalyst for organizational change. portal: Libraries and

the Academy, 4(3) 345-361. https://doi.org/10.1353/pla.2004.0052

Lilburn, J.

(2017). Ideology and audit culture: Standardized service quality surveys in

academic libraries. portal: Libraries and the Academy, 17(1),

91-110. https://doi.org/10.1353/pla.2017.0006

Maier, A. M., Moultrie, J., & Clarkson, P. J. (2012). Assessing

organizational capabilities: Reviewing and guiding the development of maturity

grids. IEEE Transactions on Engineering

Management, 59(1), 138-159. https://doi.org/10.1109/tem.2010.2077289

Matthews, J. R. (2015). Library assessment in higher education (2nd

ed.). Westport, CT: Libraries Unlimited.

McNaught, C., Lam, P., & Kwok, M. (2012). Using eLearning benchmarking as a strategy to foster institutional

eLearning strategic planning. Working Paper 11. Hong Kong: Centre for

Learning Enhancement and Research, The Chinese

University of Hong Kong. Retrieved from http://www.cuhk.edu.hk/clear/research/WP11_McNLK_2012.pdf

Mu, Y. (2012). Appraisal of library knowledge management capability

evaluation and empirical analysis. Information

studies: Theory & Application, 35(3), 83-86. Retrieved from http://en.cnki.com.cn/Article_en/CJFDTotal-QBLL201203020.htm

Oakleaf, M.

(2010). The value of academic libraries:

A comprehensive research review and report. Chicago, IL: Association of

College and Research Libraries.

Orr, R. H. (1973). Measuring the goodness of library services: A general

framework for considering quantitative measures. Journal of Documentation, 29(3), 315-332. https://doi.org/10.1108/eb026561

Paulk, M. C., Curtis, B., Chrissis, M. B.,

& Weber, C. V. (1993). Capability maturity model, version 1.1. Institute for Software Research Paper 7.

Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.1109/52.219617

Poll, R. (2016).

Bibliography on the impact and outcome of

libraries. Retrieved from http://www.ifla.org/files/assets/e-metrics/bibliography_impact_and_outcome_2016.pdf

Randall, W. M. (1932). The college library. Chicago, IL: American Library Association.

Rendon R. G. (2009). Contract

management process maturity: Empirical analysis of organizational assessments.

Monterey, CA: Naval Postgraduate School. Retrieved from https://apps.dtic.mil/docs/citations/ADA633893

Sankey, M. (2014a). Benchmarks for

technology enhanced learning: A report on the refresh project 2014 and

inter-institutional benchmarking summit. Retrieved August 11, 2015 from www.acode.edu.au/mod/resource/view.php?id=269

Sankey, M. (2014b). Benchmarking for technology enhanced learning:

Taking the next step in the journey. In B. Hegarty,

J. McDonald, and S. K. Loke (Eds.), Rhetoric and reality: Critical perspectives

on educational technology: proceedings

ascilite Dunedin 2014 (pp. 668-672). Dunedin, New

Zealand. ASCILITE.

Sheikhshoaei, F.,

Naghshineh, N., Alidousti,

S., & Nakhoda, M. (2018). Design of a digital

library maturity model (DLMM). The

Electronic Library. https://doi.org/10.1108/EL-05-2017-0114

Sputore, A.,

& Fitzgibbons, M. (2017). Assessing ‘goodness’: A review of quality

frameworks for Australian academic libraries. Journal of the Australian Library and Information Association, 66(3),

207-230. https://doi.org/10.1080/24750158.2017.1344794

Tang, K. (2012).

Closing the gap: The maturing of quality assurance in Australian university

libraries. Australian Academic &

Research Libraries, 43(2), 102-119.

Tenopir, C.,

Mays, R. N., & Kaufman, P. (2010). Lib

Value: Measuring value and return on investment of academic libraries.

School of Information Sciences. Retrieved from http://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_infosciepubs/50

Town, J. S.

(2000). Benchmarking the learning infrastructure: Library and information

services case studies. In M. Jackson, and H. Lund (Eds.), Benchmarking for Higher Education (pp. 151-164). Buckingham, England: OU Press.

Town, J. S.,

& Stein, J. (2015). Ten Northumbria Conferences: The contribution to

library management. Library Management,

36(3). https://doi.org/10.1108/LM-11-2014-0135

Urquhart, C.,

& Tbaishat, D. (2016). Reflections on the value

and impact of library and information services: Part 3: Towards an assessment

culture. Performance Measurement and Metrics, 17(1), 29-44. https://doi.org/10.1108/PMM-01-2016-0004

Wendler, R.

(2012). The maturity of maturity model research: A systematic mapping study. Information and Software Technology, 54(12), 1317-1339. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.infsof.2012.07.007

Wijetunge, P.

(2012). Assessing knowledge management maturity level of a university library:

A case study from Sri Lanka. Qualitative

and Quantitative Methods in Libraries, 1(3), 349-356. Retrieved from http://www.qqml-journal.net/index.php/qqml/article/view/70

Wilson, F.

(2013). The quality maturity model:

Assessing organisational quality culture in academic libraries (Doctoral

dissertation). London, England: Brunel University, School of Information

Systems, Computing and Mathematics. Retrieved from https://bura.brunel.ac.uk/handle/2438/8747

Wilson, F.

(2015). The quality maturity model: Your roadmap to a culture of quality. Library Management, 36(3), 258-267. https://doi.org/10.1108/LM-09-2014-0102

Wilson, F.,

& Town, J. S. (2006). Benchmarking and library quality maturity. Performance Measurement and Metrics, 7(2),

75-82. https://doi.org/10.1108/14678040610679461

Wright, S.,

& White, L. S. (2007). SPEC kit 303

library assessment. Washington, DC: Association of Research Libraries.

Yang, Z., &

Bai, H. (2009). Building a maturity model for college library knowledge

management system. International

conference on test and measurement, ICTM 2009 (pp.1-4). Hong Kong, IEEE. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICTM.2009.5412987

Yang, Z., Zhu,

R., & Zhang, L. (2016). Research on the capability maturity model of

digital library knowledge management. Proceedings

of the 2nd International Technology and Mechatronics Engineering

Conference. Chongqing, China: ITOEC. https://doi.org/10.2991/itoec-16.2016.63