Academic Librarians’ Educational Factors and

Perceptions of Teaching Transformation: An Exploratory Examination

Amanda Nichols Hess

eLearning, Instructional

Technology, and Education Librarian

Oakland University Libraries

Rochester, Michigan, United

States of America

Email: nichols@oakland.edu

Received: 18 Nov. 2018 Accepted: 12 July 2019

![]() 2019 Hess. This is an Open Access article

distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

2019 Hess. This is an Open Access article

distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

DOI: 10.18438/eblip29526

Abstract

Objective – As

information literacy instruction is an increasingly important function of

academic librarianship, it is relevant to consider librarians’ attitudes about

their teaching. More specifically, it can be instructive to consider how

academic librarians with different educational backgrounds have developed their

thinking about themselves as educators. Understanding the influences in how

these shifts have happened can help librarians to explore the different

supports and structures that enable them to experience such perspective

transformation.

Methods – The author

electronically distributed a modified version of King’s (2009) Learning

Activities Survey to academic librarians on three instruction-focused

electronic mail lists. This instrument collected information on participants’

demographics, occurrence of perspective transformation around teaching, and

perception of the factors that influenced said perspective transformation (if

applicable). The author analyzed the data for those academic librarians who had

experienced perspective transformation around their teaching identities to

determine if statistically significant relationships existed between their

education and the factors they reported as influencing this transformation.

Results – Results

demonstrated several statistically significant relationships and differences in

the factors that academic librarians with different educational backgrounds

cited as influential in their teaching-focused perspective transformation.

Conclusion – This research

offers a starting point for considering how to support different groups of

librarians as they engage in information literacy instruction. The findings

suggest that addressing academic librarians’ needs based on their educational

levels (e.g., additional Master’s degrees, PhDs, or professional degrees) may

help develop productive professional learning around instruction.

Introduction

In the shifting higher education environment, academic libraries

continually work to serve students and faculty in meaningful, responsive ways.

Library instruction represents one area where intentional evolution has

occurred: While librarians once focused on systematically presenting

information on library resources, or bibliographic instruction, their

instructional area has changed with the information landscape. As information

resources emerged in new formats and finding sources grew more multifaceted, academic

librarians shifted into information literacy instruction. Rather than focusing

on presenting library resources, information literacy is grounded in developing

learners’ capacities to “recognize when information is needed and … locate,

evaluate, and use effectively the needed information” (American Library

Association [ALA], 1989, paragraph 3). The Association of College and Research

Libraries (ACRL) supported this kind of instruction by developing the Information Literacy Competency Standards

for Higher Education (2000). This resource provided academic librarians

with information literacy outcomes they could apply across varied instructional

environments as the Information Age emerged in the early 21st

century. However, learning needs have continued to shift since that time.

The prescriptive guidelines set forth by the Standards did not reflect the

information ecosystem where understanding information access, value, and power

structures became more crucial and where academic librarians’ instruction was

situated. In 2016, ACRL sought to address these emerging needs through the Framework for Information Literacy for

Higher Education, which focused information literacy instruction on

facilitating deeper learning. This document provided threshold concepts

learners need to grasp, rather than performance outcomes they can attain, to be

information literate lifelong learners. In reframing instruction, the Framework encourages academic librarians

to consider their roles as educators in more holistic ways. While the ACRL Framework may aim to present a new—or

perhaps more nuanced—approach to information literacy, it also raised

challenges for librarians. Even if the Framework

more fully represented 21st century information dynamics, this

approach was a departure from library instruction as set forth in the ACRL Standards. Academic librarians may need

to consider how they think of themselves as educators, in response to these

changes; Scott Walter (2008) referred to this self-concept as a teacher

identity.

This research considered academic librarians’ teacher identity and, more

specifically, whether there are relationships between the experiences that

shape this self-concept and their educational background. I used transformative

learning theory as a framework with the Learning Activities Survey (King, 2009)

to collect librarians’ perception data about their experiences developing

teaching identities. I conducted cross-tab and one-way analysis of variance

(ANOVA) tests to identify statistically significant relationships between

librarians’ education and relational, experiential, and work-related factors in

developing these identities. The results show that interactions or experiences

impacted academic librarians’ teacher identity development differently,

depending on individuals’ education levels.

Other research has established that academic librarians can develop

teacher identities (Walter, 2008) and that this self-concept may emerge from a

perspective transformation process (Nichols Hess, 2018). This scholarship offers

a way to advance this scholarly agenda by more deeply understanding the inputs

academic librarians believe have influenced this component of their

professional identities. Beginning to establish such understandings can help

librarianship more effectively support information literacy instructors and

instruction.

Literature Review

First, it is important to operationalize the idea of a teacher or

teaching identity. In the most practical sense, these terms represent an

individual’s self-perception about his or her work as an educator (Beauchamp

& Thomas, 2009). Walter (2008) applied this notion more specifically to

academic librarians, identifying that their teacher identities center on how

they consider their educational roles at their institutions. However, this

professional self-concept is not limited to libraries; teaching identities have

been explored in the literature around teacher education and preparation (Agee,

2004; Friesen & Besley, 2013; Rahmawati

& Taylor, 2018, Smagorisnky, Cook, Jackson, Fry,

& Moore, 2004; Stillwaggon, 2008). In the

existing research, scholars have established teaching or teacher identities as

multifaceted, dynamic ideas that evolve throughout an individual’s career.

Since teaching identities are fluid, it is useful to consider how they

may develop with a theoretical framework focused on personal evolution and

development. Jack Mezirow’s (1978, 1981, 1994, 1997,

2000) transformative learning theory offers such a starting point. His work is

built on the idea that adults use their experiences to make meaning of the

world around them but that they can fall back onto ideas or schema adopted from

others (e.g., authority figures, perceived experts, family, friends) and not

personally evaluated (Mezirow, 1997). Transformation,

then, happens when adults consider the environment in which they exist and

establish their own beliefs and values based on biographical, social, and

cultural experiences. More specifically, “perspective transformation” happens.

Adults have internal cognitive “frames of reference” they use to make sense of

the world, and these frames are composed of “habits of mind” (Mezirow, 1978). While frames of reference are broader ways

adults view situations, groups, and interactions, habits of mind are more

specifically grounded in the snap judgments or interpretations adults make (Mezirow, 1997). From these frames of reference and habits

of mind, adults then present external-facing points of view (Mezirow, 1997). These frames of reference and habits of

mind may change with inputs from individuals’ experiences in the world (Mezirow, 1978, 1994, 2000); in such instances,

external-facing points of view also shift. Having these transformative

experiences leads adults to develop more authentic senses of selves.

Researchers have applied transformative learning theory to understand

how disciplinary faculty in higher education engage in developing teaching

identities (Balmer & Richards, 2012; Cranton

& Carusetta, 2004; Post, 2011). Neither this

scholarship nor the research on K-12 teacher identities can be applied

wholesale to academic librarians, though. Academic librarians’ teaching

practices are considerably different from either K-12 educators or subject-area

faculty; thus, they may have unique needs or experiences in forming, or

transforming, how they see themselves as educators. Therefore, the scholarship

on academic librarians’ educational experiences influences how these

transformational experiences can be understood. These may be related to their

library-focused graduate education, the informal or professional learning they

engage in within the field, or any other formal degree-granting programs

pursued outside of librarianship. This focus area does not exist in the

research literature on disciplinary faculty’s teaching identity development and

transformative learning, since they generally hold doctoral degrees in their

subject area. The research from the library literature in this area can both

consider academic librarians’ unique experiences as educators and provide important

context.

Researchers have established that academic librarians generally

experience limited or inadequate exposure to information literacy in library

school (Bailey, Jr., 2010; Corral, 2010; Sproles, Johnson, & Farison, 2008). As such, academic librarians may engage in

post-graduate training or education around instructional practices and

educational identity development. In fact, scholars have demonstrated that new

professionals enter the field expecting to engage in this kind of job-specific

training that offer opportunities to enhance their skills and gain knowledge

not addressed in their academic experiences (Sare,

Bales & Neville, 2012). Moreover, researchers conducting a study of 788

Canadian library staff with instructional responsibilities found that many used

self-directed or self-selected postgraduate professional learning experiences

(e.g., attending workshops, reviewing the literature) or informal job-based

learning offerings to prepare for their teaching responsibilities (Julien &

Genuis, 2011). Other scholars have focused on how

librarians have used such resources, including job-embedded professional

learning (Click & Walker, 2010; Nichols Hess, 2016; Shamchuk,

2015; Walter, 2006), instruction-centric institutional offerings (Hoseth, 2009; Otto, 2014), and a variety of professional

mentorship relationships (James, Rayner, & Bruno, 2015; Lorenzetti & Powelson, 2015; Mavrinac, 2005)

to support their own teaching identity development. These researchers’ works

emphasize that academic librarians only begin to learn the pedagogical

essentials after they earn Master’s of Library or

Information Science (MLIS) degrees.

While some academic librarians pursue ongoing informal professional

development, others elect more formal educational options. Librarians who have

in-depth liaison relationships with academic units may find that additional

degrees—Master’s, professional (e.g., JD, specialist certificates), or

PhDs—offer opportunities to deepen subject knowledge and develop pedagogical

competencies. While this route is not uncommon, there is not broad agreement on

whether such education is necessary—or helpful—to the profession (Crowley,

2004; Ferguson, 2016; Mayer & Terrill, 2005). Researchers have demonstrated

that those who had attained doctorates in subject areas felt this experience

gave them credibility with faculty, expertise in their instructional

disciplines, and deep research experience they could use to connect with

students (Gilman & Lindquist, 2010). However, these librarians indicated that

additional education was not the only route to gain advanced subject knowledge;

they cited on-the-job experience and other learning undertakings as real

difference-makers in developing their disciplinary understandings, not

credentials or degrees.

Aims

Using the teaching identity concept, transformative

learning theory, and the existing research on how academic librarians’

educational experiences impact their professional identity, I investigated the

following question: How do academic librarians’ educational experiences (i.e.,

education level, additional degrees) interact with external inputs (e.g.,

relationships, professional experiences) to influence their teaching identity

development?

This inquiry builds on research establishing that

academic librarians can experience perspective transformation around their

teaching identities and that different types of hands-on experiences as

educators may shape these identities in different ways (Nichols Hess, 2018).

This existing scholarship identified an area for inquiry around academic

librarians’ teaching identities and perspective transformation. This research,

then, sought to advance this topic by considering whether academic attainment

influenced how academic librarians’ teaching identity development happened.

Methods

Research Approach

I used an exploratory perspective to further develop this research area

in the library literature. I used a modified version of Kathleen P. King’s

(1997, 2009) Learning Activities Survey (LAS; see Appendix A) to solicit a

voluntary sample from academic librarians engaged in instruction. The LAS is

grounded in transformative learning theory. Respondents reflect on whether they

believe they have experienced perspective transformation and indicate which

inputs they believe have influenced such experiences. Although other

researchers have explored librarians’ teaching-based perspective transformation

in qualitative ways (Walter, 2008), I chose a survey instrument to collect

deductive data from a large group of academic librarians. While the exploratory

study design did not generate generalizable data, it does establish a

foundation on which other researchers can construct related scholarship. All

appropriate regulatory approvals from my university research board were received

before data collection began.

Survey Modification, Distribution, and Data Collection

King (2009) developed, copyrighted, demonstrated the reliability of, and

validated the LAS. She encouraged researchers to use or modify her instrument,

gratis, so long as she was credited; other researchers have used King’s LAS to

examine specific populations’ cognitive and behavioral transformations (see,

for example, Brock, 2010; Kitchenham, 2006; Kumi-Yeboah & James, 2014). King provided specific

modification guidelines to preserve the instrument’s integrity (King, 2009, pp.

36-44). In this research context, I modified the LAS per King’s directions to

ground librarians’ transformative experiences around their teaching in the

broader body of research while maintaining the instrument’s reliability.

Any version of the LAS has three types of questions:

- Demographic items;

- Items that ask respondents to indicate whether

perspective transformation has occurred; and

- Items about what inputs impacted an individual’s

perspective transformation process.

Questions related to whether individuals have experienced perspective

transformation should not be altered except to provide relevant contextual

information. Researchers must review participants’ responses to generate perspective

transformation index (PT-Index) groupings using a standard set of procedures

(King, 2009). This baseline metric determines whether individuals report

experiencing perspective transformation, and it establishes a sub-group of

participants that the researcher can use for subsequent analyses. I adhered to

these guidelines when examining academic librarians’ experiences with

perspective transformation around their teaching identities.

I built the new version of the LAS in Qualtrics and distributed the survey

instrument via email to three information literacy-focused electronic mailing

lists (acrlframe-l, infolit-l,

and lirt-l) to recruit a voluntary sample; 501

individuals responded. At the time of distribution, this figure represented

between a 5.9% (total overlap in list membership) and 8.1% (no overlap in list

membership) response rate. While anyone could participate in the survey, those

who indicated that library instruction or information literacy was not part of

their job responsibilities were automatically directed to the end of the

instrument. The survey was open from February 6 to April 6, 2017; all

incomplete responses were automatically recorded when the survey closed.

Preparatory Procedures: Identifying Perspective Transformation

Per King’s (2009) directions, all respondents were assigned to a

PT-Index designation. This information reflects participants’ responses to four

items on the LAS, and it “indicates whether [learners] have experienced a

perspective transformation” (King, 2009, p. 38). On this version of the LAS,

those four questions were:

●

Item 14: Think about your professional experiences in

teaching—check off any of the following statements that apply.

●

Item 15: Since you have been providing information

literacy instruction, do you believe you experienced a time when you realized

that your values, beliefs, opinions, or expectations (for example, how you

viewed your work responsibilities or roles as an academic librarian) changed?

●

Item 16: Describe what happened when you realized your

values, beliefs, opinions, or expectations about your instructional

responsibilities had changed.

●

Item 20: Think back to when you first realized that

your views or perspective had changed. What did your professional life have to

do with the experience of change?

To identify the PT-Index designations of all 501 participants, I first

identified individuals who had checked at least one of the affirmative

statements in Item 14 or who had indicated “Yes” or “I’m not sure” in response

to Item 15. These individuals were initially classified in a YES PT-Index

group. Individuals who had not selected any of the affirmative statements about

transformation in Item 14 or had indicated “No” to Item 15 were categorized

into a NO PT-Index group. I then reviewed respondents’ free-text comments for

Items 16 and 20 to affirm or modify these group assignments as needed.

While a total of 501 individuals responded, 353 survey participants were

ultimately classified as YES PT-Index group members, or as individuals who had

reported experiencing perspective transformation around their teaching

identities in some way. Those in the NO PT-Index group were excluded from all

additional analyses.

Preparatory Procedures: Identifying Transformative Constructs

The next goal was to understand what factors had influenced the

respondents’ perspective transformation. On Items 17 to 19 of the LAS,

participants identified the relationships, experiences, or resources, and

professional events they believed had influenced their teaching identity

development. There were 41 potential inputs across these three items, and

participants could select all that applied. Analyses between demographic

categories and each of the inputs individually would not provide meaningful

data. Instead, I used SPSS to conduct a principal component analysis using

Varimax (orthogonal) rotation followed by a subsequent confirmatory factor

analysis on participants’ responses to each item to identify transformative

constructs for relationship-, experience-, and professionally centric inputs.

In this type of analysis, statistical tests were used to examine where

participants selected common variables in response to each question separately;

this process helped to identify where links existed across participants’

responses to a single question.

The principal component analysis reduced 41 variables from three items

into 12 transformative constructs that participants indicated had influenced

their teaching identity development process. The resulting confirmatory factor

analysis was used to identify the connections and build these constructs; they

each had eigenvalues greater than 1.0 and significant factor criterion of at

least 0.4. I used the inputs within each construct to determine the terms used

to describe each construct’s core ideas.

In response to item 17 on the LAS, the relationship-centric constructs

that influenced participants’ teaching identity development were:

●

Supportive interpersonal relationships, which was comprised

of six inputs related to the positive relationships

participants developed laterally—such as with colleagues and disciplinary

faculty—as well as their interactions with students

●

Motivating leaders, which was comprised of four inputs

related to the relationships participants had with

their work mentors, supervisors, and administrators in more of a top-down

structure

●

Challenging colleagues, which was comprised of three

inputs related to participants’ negative interactions (e.g., criticism,

negative feedback, comments on issues with instruction) with colleagues, other

librarians, and disciplinary faculty

●

Other important relationships, which was comprised of

other relationship-centric inputs participants could include

In response to item 18 on the LAS, the experience-centric constructs

that influenced teaching participants’ identity development were:

●

Professional learning, which was comprised of seven

inputs related to participants engaging with diverse readings on teaching,

attending professional development workshops, and observing other

librarians’ instruction

●

Writing and technology-rich teaching, which was

comprised of four inputs related to participants’ experiences teaching online

or in hybrid environments and writing about teaching practices for publication

●

External feedback, which was comprised of three inputs

related to participants’ experiences observing disciplinary faculty’s teaching,

receiving comments from students, and getting feedback from disciplinary

faculty

●

Library-centric input, which was comprised of three

experiential inputs related to participants’ library school coursework,

engaging in discussion with other librarians about their instructional

practices, and completing teaching self-reflections

●

Self-reflection and other experiences, which was

comprised of two inputs related to participants’ use of reflection journals,

and other experience-centric inputs participants could include

In response to item 19 on the LAS, professionally centric constructs

that influenced teaching participants’ identity development were:

·

Completing graduate education, which was comprised of

two inputs related to participants’ library and non-library program graduation

(that is, not their education level itself—but that the experience of

completing an educational program had impacted these participants’ senses of

themselves as educators)

·

Changing job statuses, which was comprised of three

inputs related to participants’ first professional job, changes in professional

jobs, or job losses

·

Other shifting responsibilities, which was comprised

of two inputs related to participants’ changing work duties and other

work-centric inputs participants could include

Because there is overlap between relationship-, experience-, and professionally

centric inputs, there are some similarities between the resulting constructs.

However, each of the original inputs aligned with only one transformative

construct. One experience-centric input—teaching face-to-face—did not align

with a specific transformative construct. This outlier existed because 179

respondents (of the 353 individuals in the YES PT-Index group) selected this

input as an influence in shaping their teaching identity. Face-to-face

teaching, then, influenced teaching identity transformation across

participants’ other experiences rather than aligning as part of a particular

construct. This input was maintained in subsequent data analysis.

Preparatory Procedures: Transforming Participants’ Responses to Z-Scores

I transformed participants’ (n

= 353) combined responses for the inputs in each of the 12 transformative

constructs into composite scores. This data transformation allowed for the

analysis of perceptions of how the 12 constructs had influenced perspective

transformation around teaching identities. SPSS was used to generate these

responses into standardized Z-scores, and this process allowed for comparison

of how constructs composed of diverse numbers of inputs influenced participants

across demographic items. In these Z-scores, 0 is the mean, and one unit

indicates a standard deviation in the sample. The probability of a score

occurring within a normal distribution from these standard scores could then be

calculated.

The preparatory procedures involved considerable data-related work, but

the values generated in these processes (i.e., eigenvalues/factors associated

with 12 transformative constructs) were not used in any subsequent analyses.

Rather, these steps allowed for cleaning the data as a prerequisite step to

examining whether differences existed among how librarians across educational

experiences experienced perspective transformation related to their teaching.

These distinctions between the preparatory procedures and data analysis process

are represented in Figure 1.

Data Analysis: Crosstab Analysis and One-Way ANOVA

After establishing the following:

●

which participants believed they had experienced

perspective transformation around their teaching (n = 353),

●

the 12 transformative constructs and one input that

impacted these transformative processes, and

●

participants’ composite Z-scores that reflected their

responses to the 12 transformative constructs,

I analyzed whether different constructs or one input affected

participants’ teaching identity transformation processes in relation to their

education levels.

In the instance of the one remaining input—teaching face-to-face—I used

SPSS to run cross-tabulation analysis with a chi-square test statistic to

consider its relationship to librarians’ teaching identity development. This

type of analysis determines whether statistically significant relationships

exist between categorical independent variables (e.g., education level,

education beyond an MLIS) and categorical dependent variables (i.e., whether

teaching face-to-face had influenced perspective transformation). Librarians’

responses to this item were analyzed this way because this input did not align

with a single transformative construct. The standard alpha level of .05 was

used to argue for significance for this analysis.

Figure

1

A

visual representation of the data preparatory and analysis processes.

SPSS was used to conduct ANOVA tests and explore whether there were

statistically significant relationships between librarians’ education levels

and the 12 transformative constructs. When comparing multiple groups within a

population, the one-way ANOVA compares means in relation to a single variable

(e.g., a transformative construct). One-way ANOVA is appropriate when the

independent variable is categorical (i.e., mutually exclusive options) and the

dependent variables are continuous (i.e., points on a fixed scale). In this

research, participants’ responses to the demographic questions about their

education levels and additional education beyond the MLIS—the independent

variables—were categorical. The compiled data for the 12 transformative

constructs are continuous data because participants’

responses were transformed into Z-scores. One-way ANOVA, then, is the most

useful way to examine whether librarians with different educational or

work-related backgrounds felt that different transformative constructs

influenced their teaching identity development. Since one-way ANOVA only

identifies whether differences exist between groups, Fisher’s Least Significant

Distance (LSD) post-hoc comparison tests were used to examine where those

differences existed between groups to more fully understand the statistical

results. I used the standard alpha level of .05 to argue for significance for

this analysis.

Results

Overall Education Level

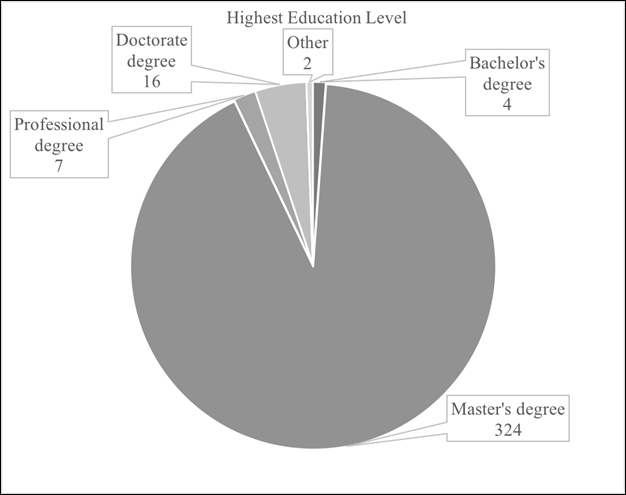

Participants who had experienced perspective transformation around their

teaching identities (n = 353) were

largely homogeneous in their overall education level. Of these respondents, 324

held Master’s degrees, followed by 16 who had earned doctorate degrees. Seven

participants held professional degrees (e.g., MBA, JD), while four held

bachelor’s degrees and two respondents had some other level of education (see

Figure 2).

Figure 2

Participants’

(n = 353) highest education levels.

No statistically significant differences existed

between participants’ highest education levels and whether they believed any of

the 12 transformative constructs or teaching face-to-face had influenced their

teaching identity development. These constructs and input, then, seemed to

similarly impact librarians’ teaching identities across overall education

levels. However, participants’ overall education level did not represent the

granularity of their graduate learning experiences—for instance, the Master’s

degree demographic group included those with an MLIS, those with additional

Master’s degrees in other subject areas, and potentially those currently in

graduate programs (Master’s, professional, or doctorate). Therefore, I

considered these components in greater detail to more fully understand academic

librarians’ educational experiences and the impacts that affected their

teaching identity development.

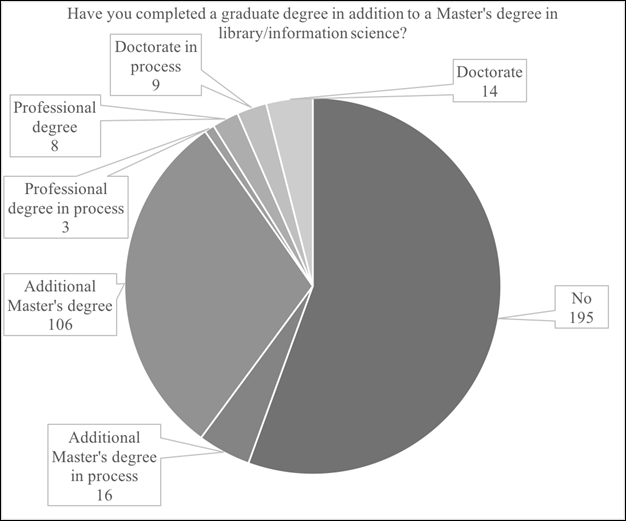

Figure 3

Participants’

(n = 352) additional degrees.

Additional Education beyond the MLIS

While the MLIS is considered the terminal degree in the field

(Association of College and Research Libraries [ACRL], 2018), participants who

had experienced perspective transformation around their teaching identities

also shared information about additional graduate experiences. Of the

participant sub-group who responded to this item (n = 352; one person did not respond), 195 had no additional degree.

Those participants who already held additional degrees included 106 with

additional Master’s degrees, 14 with doctorates, and eight with professional

degrees. Some participants had degrees in process: 16 respondents were working

to complete additional Master’s degrees, while nine were completing doctorates

and three were completing professional degrees (see Figure 3).

A chi-square test of independence was used to examine whether there were

statistically significant relationships between respondents’ additional

education and the impact of teaching face-to-face on teaching identity

transformation. The relation between these variables was not significant, X2 (7, n = 352) = 3.40, p >

.05. These data suggest that the impact of teaching face-to-face does not

influence librarians’ teaching identity transformation

differently across additional degree levels.

Table

1

Impact

of the Motivating Leaders Construct on Teaching Identity Transformation for

Academic Librarians with Education beyond an MLIS

|

Additional

Education |

Significantly Different from: |

Mean

as a Z-score

|

Standard

Deviation |

|

Professional

degree (n = 8) |

Professional

degree in process* |

-0.34 |

0.56 |

|

Additional

Master’s (n = 106) |

Professional

degree in process* Doctorate in

process* |

-0.20 |

0.85 |

|

Doctorate (n = 14) |

Professional

degree in process* |

-0.19 |

0.77 |

|

No additional

degree (n = 195) |

Professional

degree in process* |

0.06 |

1.30 |

|

Additional

Master’s in process (n = 6) |

No other

educational level |

0.28 |

1.27 |

|

Doctorate in

process (n = 9) |

Additional

Master’s* |

0.71 |

1.82 |

|

Professional

degree in process (n = 3) |

No additional

education* Additional

Master’s* Professional

degree* Doctorate* |

1.44 |

2.72 |

*p <

.05

Based on librarians’ reported education in addition to an MLIS, I

observed differences in the role that motivating leaders (F [6, 344] = 2.214, p =

.041), writing and technology-rich teaching (F [6, 344] = 4.219, p

< .001), and library-centric input (F [6,

344] = 4.184, p = .005) played in their perspective transformation around

teaching identities. Tables 1 to 3 illustrate the differences observed for

these three components. The first column lists participants’ education levels;

in the second column, the groups where differences occurred are presented,

along with the appropriate p values.

The third column presents the means (represented as Z-scores) organized in

ascending order, and the fourth column contains standard deviations.

In the case of motivating leaders, those librarians pursuing doctorate

and professional degrees were more likely to cite this construct as a component

in their teaching identity transformation 0.71 and 1.44 standard deviations above the mean, respectively (see Table

1). In contrast, those respondents with professional, additional Master’s, and

doctorate degrees cited motivating supervisors 0.34, 0.20, and 0.19 standard

deviations below the mean,

respectively. These data suggest that those participants with additional

graduate degrees did not believe that motivation from supervisors had

influenced their perspective transformation around their teaching identities,

while those with degrees in process may have held different perceptions.

Table

2

Impact

of the Writing and Technology-Rich Teaching Construct on Teaching Identity Transformation

for Academic Librarians with Education beyond an MLIS

|

Additional

Education |

Significantly

Different from: |

Mean

as a Z-score

|

Standard

Deviation |

|

Professional

degree (n = 8) |

Professional

degree in process* Doctorate in

process* |

-0.24 |

0.87 |

|

No additional

degree (n = 195) |

Professional

degree in process* Doctorate in

process** |

-0.01 |

1.03 |

|

Additional

Master’s in process (n = 6) |

Professional

degree in process* Doctorate in

process* |

-0.01 |

1.03 |

|

Additional

Master’s (n = 106) |

Professional

degree in process* Doctorate in

process** |

0.16 |

1.16 |

|

Doctorate (n = 14) |

Doctorate in

process* |

0.26 |

1.42 |

|

Professional

degree in process (n = 3) |

No additional

education* Additional

Master’s in process* Additional Master’s* Professional

degree* |

1.61 |

2.01 |

|

Doctorate in

process (n = 9) |

Additional

Master’s in process* Additional Master’s** Professional

degree* Doctorate* |

1.62 |

1.78 |

*p < .05

**p < .001

Similarly, those respondents pursuing professional or

doctorate degrees were more likely to indicate that writing and technology-rich

teaching had influenced their transformation around their teaching identities

(see Table 2). These individuals cited the influence of writing and

technology-rich teaching in their teaching identity development processes 1.61

(professional degree in process) and 1.62 (doctorate in process) standard

deviations above the mean. These

results suggest that these groups of academic librarians may be more likely to

report having experienced teaching-related perspective transformation because

of writing and technology-rich teaching than their colleagues with different

educational backgrounds.

Those individuals who held professional degrees or

were earning doctorates were more likely to report having experienced a shift

in their perspectives based on library-centric input rather than external

feedback (see Table 3). Individuals with these degrees reported that this

construct had influenced their teaching identity development 1.12 and 1.33

standard deviations above the mean, respectively. Interestingly, though,

respondents with doctorates were less likely—0.32 standard deviations below the

mean—to cite library-centric input as having played a role in their perspective

transformation. These data suggest there are differences in how library-centric

feedback impacts librarians’ teaching identity development across educational

backgrounds.

Table

3

Impact

of the Library-Centric Input Construct on Teaching Identity Transformation for

Academic Librarians with Education beyond an MLIS

|

Additional

Education |

Statistically

Different from: |

Mean

as a Z-score |

Standard

Deviation |

|

Doctorate (n = 14) |

Professional

degree* Doctorate in

process* |

-0.32 |

0.96 |

|

Professional

degree in process (n = 3) |

No other

educational level |

-0.22 |

0.43 |

|

Additional

Master’s (n = 106) |

Professional

degree* Doctorate in

process* |

-0.09 |

1.02 |

|

Additional

Master’s in process (n = 16) |

Professional

degree* Doctorate in process* |

0.03 |

1.01 |

|

No additional

degree (n = 195) |

Professional

degree* Doctorate in

process* |

0.15 |

1.19 |

|

Professional

degree (n = 8) |

No additional

education* Additional

Master’s in process* Additional

Master’s* Doctorate* |

1.12 |

1.76 |

|

Doctorate in

process (n = 9) |

Additional

Master’s in process** Additional

Master’s** Doctorate* |

1.33 |

1.77 |

*p < .05

**p < .001

Discussion

When viewed through the transformative learning theoretical framework as

well as existing literature on academic librarians’ educational experiences,

these results suggest several relevant, practical takeaways. While elsewhere I

have established that academic librarians believe they experience perspective

transformation around their teaching identities (Nichols Hess, 2018), these

data suggest how education-related inputs differently impact academic

librarians’ experiences in forming teaching identities. Furthermore, they build

on other teaching identity-related research to better understand how academic

librarians develop this facet of their self-concept (Julien & Genuis, 2011; Shamchuk, 2015;

Walter, 2006, 2008). These findings also reinforce Mezirow’s

(1994, 1997, 2000) assertion that external experiences, relationships, and

environments affect individuals’ self-concepts in different ways. While this

study’s conclusions are exploratory and suggestive, the statistically

significant differences present ideas for individual librarians and library

leaders to consider for ongoing teaching identity development.

There were several areas where academic librarians’ educational

experiences influenced the transformative constructs important to their

teaching identities. For example, the author’s data analysis suggested that

those with education beyond an MLIS experienced shifts in their thinking about

their teaching in different ways from their peers who held the terminal degree.

Individuals who pursued professional or doctorate degrees indicated that

transformation around their teaching identities had been influenced more by

motivating leaders. Perhaps this top-down motivation for instructional identity

development came from supervisors’ beliefs that these academic librarians were

instructional leaders or their desire to see these individuals act as

pedagogical champions. Academic librarians’ professional or doctoral education,

then, may have outwardly manifested their developing teaching identities to

those in leadership roles in different ways.

In addition to leadership’s top-down influence in shaping their teaching

identities, those academic librarians with doctorates indicated that

library-based feedback was less influential in their transformative experiences

than many of their peers. This kind of feedback included comments from other

librarians—both at and outside of their institutions—and from library school

faculty. This demographic group was relatively small, but they may have also

interacted with both colleagues and faculty outside of librarianship in

different ways. As such, it makes sense that those instructional librarians

with doctorate-level education would find instructional communities outside of

the library, including with disciplinary faculty, to be useful in developing

their teaching identities.

Moreover, several groups of librarians with education beyond an MLIS,

including those with doctorates and additional Master’s degrees, indicated that

writing and technology-rich teaching had positive impacts on their

teaching-related perspective transformations. Librarians with these educational

backgrounds may find it useful to pursue these kinds of experiences more

intentionally as they seek to further hone their instructional identities. For

instance, academic librarians may find it instructive to embed in online or

hybrid courses more intentionally. There are myriad ways to make such

connections, including being embedded in a learning management system, offering

synchronous online instructional support, and developing freestanding

e-learning modules. Librarians with doctorates or additional Master’s degrees

may find these experiences help them consider their teaching identities in new

ways. Also, librarians with experience with data collection and analysis in

Master’s or doctoral programs should seek opportunities to apply these

experiences to writing about their instructional practices. Such additions to

information literacy-centric scholarship would deepen the field’s research

corpus, could inspire other academic librarians to develop their teaching

identities, and may engage those librarians with additional Master’s or

doctorates in more fully considering their educational expertise.

Similarly, library leaders may also want to investigate how they can provide

these kinds of opportunities to their academic librarians with additional

degrees. At a broader level, though, it may be worth considering whether these

academic librarians feel more equipped or have more frequent opportunities to

engage in writing and technology-rich teaching. If so, academic librarians may

find it useful to consider what experiences from these kinds of degree-granting

programs could benefit individuals in MLIS programs or on-the-job learning

experiences.

Limitations

While this research identified statistically significant differences in

academic librarians’ education, work experiences, and transformative inputs in

developing teaching identities, there are several important limitations to

consider. This research is suggestive only; it does not present, or attempt to

present, any causal relationships. Moreover, the size of these groups may have

impacted the effect size. And it is important to consider when individuals

earned any additional graduate training. The timing of additional degrees

(e.g., before or after an MLIS, earned well before working as an academic

librarian) may influence individuals’ experiences. However, this version of the

LAS did not ask participants for such information. Future research that can

mitigate these constraints would help to better contextualize the author’s

findings in this study.

Implications for Instructional Practice

There are several practical takeaways for academic

librarians and library leaders who support teaching identity development.

Individuals’ responses to this survey highlighted that librarians with

different academic backgrounds may find different supports beneficial for

perspective transformation around teaching. Since instruction librarians have a

variety of educational backgrounds—including additional Master’s degrees,

professional degrees, and doctorates—it is useful for the profession to

acknowledge that learning, development, and motivation experiences impact

academic librarians in different ways. Acknowledging these differences is the

first step to providing the appropriate support for academic librarians’

teaching identity development, and it can help librarians, supervisors, and

library administrators to develop personalized or focused plans for

individuals’ professional development. For example, those with advanced

education may find supervisor-based mentorship useful, either within the

library or at their institution more broadly. These librarians may also find it

helpful to pursue supportive interpersonal relationships outside of

librarianship, whether at their institutions (e.g., workshops at teaching and

learning centers) or in other environments (e.g., teaching conferences, social

media, teaching-focused electronic mailing lists). Conversely, those academic

librarians who hold an MLIS may find it most beneficial to develop

library-centric relationships, both within their own institutions and across

the profession, that focus on teaching approaches, instructional practices, and

education-centered reflection. These kinds of experiences may help these

professionals to more intentionally develop their teaching identities.

More intentional research with those academic

librarians who hold doctorates, work in instruction, and have experienced

transformation around their teaching identities may be useful in this case. And

more broadly, academic library administrators who work with librarians who hold

education beyond an MLIS should investigate how they can support these

individuals’ perspective transformation around teaching. Doing so may benefit

both those librarians’ practices and the libraries’ broader information

literacy instruction programs.

Conclusion

In this study, I analyzed data from academic librarians who indicated

they had experienced perspective transformation around their teaching identity

to determine if there were relationships to individuals’ educational

backgrounds and transformative inputs. I used one-way ANOVA with 12

transformative constructs and cross-tab analysis with one categorical input to

identify where differences existed between these demographic categories. The

results show that there are some statistically significant differences between

academic librarians’ educational levels and the inputs they believe have

influenced their perspective transformation processes.

Researchers can conduct additional, focused scholarship to determine how

to best understand and act on these relationships. For example, survey research

with librarians with additional Master’s, professional, or doctorate degrees

may help frame how they experience shifts in their thinking and practices

around their instructional identities. Moreover, interviews with an intentional

sampling of librarians from these groups may provide more in-depth insight into

how librarians’ educational backgrounds influence the effects of different

transformative inputs on their senses of themselves as educators. These kinds

of follow-up studies may help us to both better understand different academic

librarians’ instruction-driven perspective transformation experiences and

provide opportunities that promote such shifts in thinking.

References

Agee, J. (2004). Negotiating a teaching identity: An

African American teacher's struggle to teach in test-driven contexts. Teachers College Record, 106(4), 747-774.

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9620.2004.00357.x

American Library Association. (1989, January 10). Presidential Committee on Information

Literacy: Final Report. Retrieved from

http://www.ala.org/acrl/publications/whitepapers/presidential

Association of College and Research Libraries. (2018,

April). Statement on the terminal

professional degree for academic librarians. Retrieved from http://www.ala.org/acrl/standards/statementterminal

Association of College and Research Libraries. (2016).

Framework for Information Literacy for

Higher Education. Retrieved from http://www.ala.org/acrl/standards/ilframework

Association of College and Research Libraries. (2000).

Information Literacy Competency Standards

for Higher Education. Retrieved from https://alair.ala.org/bitstream/handle/11213/7668/ACRL%20Information%20Literacy%20Competency%20Standards%20for%20Higher%20Education.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

Bailey, Jr., E. C. (2010). Educating future academic librarians: An

analysis of courses in academic librarianship. Journal of Education for Library and Information Science, 51(1),

30-42.

Balmer, D. F., & Richards, B. F. (2012). Faculty development as

transformation: Lessons learned from a process-oriented program. Teaching and Learning in Medicine, 24(3),

242-247. https://doi.org/10.1080/10401334.2012.692275

Beauchamp, C., & Thomas, L. (2009). Understanding

teacher identity: An overview of issues in the literature and implications for

teacher education. Cambridge Journal of

Education, 39(2), 175-189. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057640902902252

Brock. S. E. (2010). Measuring the importance of

precursor steps to transformative learning. Adult

Education Quarterly, 60(2),

122-142. https://doi.org/10.1177/0741713609333084

Click, A., & Walker. C. (2010). Life after library

school: On-the-job training for new instruction librarians. Endnotes: The Journal of the New Members

Round Table, 1(1), 1-14.

Retrieved from http://www.ala.org/rt/sites/ala.org.rt/files/content/oversightgroups/comm/schres/endnotesvol1is1/2lifeafterlibrarysch.pdf

Cranton, P., & Carusetta, E. (2004). Perspectives on authenticity in

teaching. Adult Education Quarterly, 55(1),

5-22. https://doi.org/10.1177/0741713604268894

Crowley, B. (2004). Just another field? LIS programs can, and should,

reclaim the education of academic librarians. Library Journal, 129(18),

44-46.

Ferguson, J. (2016). Additional degree required? Advanced subject

knowledge and academic librarianship. portal:

Libraries and the Academy, 16(4), 721-736. https://doi.org/10.1353/pla.2016.0049

Friesen, M. D., & Besley, S. C. (2013). Teacher

identity development in the first year of teacher education: A developmental

and social psychological perspective. Teaching

and Teacher Education, 36, 23-32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2013.06.005

Gilman, T., & Lindquist, T. (2010)

Academic/research librarians with subject doctorates: Experiences and

perceptions, 1965-2006. portal: Libraries

and the Academy, 10(4), 399-412. https://doi.org/10.1353/pla.2010.0007

Hoseth, A. (2009). Library participation in a campus-wide teaching program. Reference Services Review, 37(4),

371-385. https://doi.org/10.1108/00907320911006985

Julien, H., & Genuis, S.

K. (2011). Librarians’ experiences of the teaching role: A national survey of

librarians. Library & Information

Science Research, 33(2), 103-111. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lisr.2010.09.005

King, K. P. (1997). Examining activities that promote

perspective transformation among adult learners in higher education. International Journal of University Adult

Education, 36(3), 23-37.

King, K. P. (2009). The handbook of the evolving research of transformative learning based

on the Learning Activities Survey. Charlotte, NC: Information Age

Publishing.

Kitchenham, A. (2006). Teachers and technology: A transformative journey. Journal of Transformative Education, 4(3),

202-225. https://doi.org/10.1177/1541344606290947

Kumi-Yeboah, A., & James, W. (2014). Transformative learning experiences

of international graduate students from Asian countries. Journal of Transformative Education, 12(1), 25-53. https://doi.org/10.1177/1541344614538120

Lorenzetti, D. L., & Powelson,

S. E. (2015). A scoping review of mentoring programs for academic librarians. Journal of Academic Librarianship, 41(2),

186-196. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2014.12.001

Mavrinac, M. A. (2005). Transformational leadership: Peer mentoring as

values-based learning process. portal:

Libraries and the Academy, 5(3), 391-404. https://doi.org/10.1353/pla.2005.0037

Mayer, J., & Terrill, L.

J. (2005). Academic librarians’ attitudes about advanced-subject

degrees. College & Research

Libraries, 66(1), 59-73. https://doi.org/10.5860/crl.66.1.59

Mezirow, J. (1978).

Perspective transformation. Adult

Education Quarterly, 28(2), 100-110.

Mezirow, J. (1981). A

critical theory of adult learning and education. Adult Education Quarterly, 32(1), 3-24.

Mezirow, J. (1994).

Understanding transformation theory. Adult

Education Quarterly, 44(4), 222-232.

Mezirow, J. (1997).

Transformative learning: Theory to practice. New Directions for Adult & Continuing Education, 74, 5-12

Mezirow, J. (2000).

Learning to think like an adult. In J. Mezirow and

associates (Eds.), Learning as

transformation: Critical perspectives on a theory in progress (pp. 3-33).

San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2000.

Nichols Hess, A. (2018). Trasnforming academic

library instruction: Shifting teaching practices to reflect changed

perspectives. New York: Rowman & Littlefield.

Nichols Hess, A. (2016). A case study of job-embedded

learning. portal: Libraries and the

Academy, 16(2), 327-347. https://doi.org/10.1353/pla.2016.0021

Otto, P. (2014). Librarians, libraries, and the

scholarship of teaching and learning. New

Directions for Teaching and Learning, 139,

77-93. https://doi.org/10.1002/tl.20106

Post, P. A. (2011). Trial by hire: The seven stages of

learning to teach in higher education. Contemporary

Issues in Education Research, 4(12), 25-35. https://doi.org/10.19030/cier.v4i12.6659

Rahmawati, Y., & Taylor, P. (2018). “The fish becomes aware of the water in

which it swims”: Revealing the power of culture in shaping teaching identity. Cultural Studies of Science Education, 13(2),

525-537.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s11422-016-9801-1

Sare, L., Bales, S., & Neville, B. (2012). New academic librarians and

their perceptions of the profession. portal:

Libraries and the Academy, 12(2), 179-203. https://doi.org/10.1353/pla.2012.0017

Shamchuk, L. (2015). Professional development on a budget: Facilitating learning opportunities for information literacy

instructors. Partnership: The Canadian

Journal of Library and Information Practice and Research, 10(1), 1-14. https://doi.org/10.21083/partnership.v10i1.3437

Smagorinsky, P., Cook, L. S., Jackson, A. Y., Fry, P. G., & Moore, C. (2004).

Tensions in learning to teach: Accommodation and the development of a teaching

identity. Journal of Teacher Education,

55(1), 8-24. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022487103260067

Sproles, C., Johnson, A. M., & Farison,

L. (2008). What the teachers are teaching: How MLIS programs are preparing

academic librarians for instructional roles. Journal of Education for Library and Information Science, 49(3), 195-209.

Stillwaggon, J. (2008). Performing for the students: Teaching identity and the

pedagogical relationship. Journal of

Philosophy of Education, 42(1), 67-83. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9752.2008.00603.x

Walter, S. (2008). Librarians as teachers: A qualitative inquiry into

professional identity. College &

Research Libraries, 69(1), 51-71. https://doi.org/10.5860/crl.69.1.51

Walter, S. (2006). Instructional improvement: Building capacity for the

professional development of librarians as

teachers. Reference and User Services

Quarterly, 45(3), 213-218.

Appendix A

Survey Instrument

1. Do you agree to participate in this study?

- Yes, I agree to participate in this study.

- No, I do not agree to participate in this study.

2. Is information literacy instruction part of your current work

responsibilities?

- Yes

- No

3. Gender

- Prefer not to say

- Male

- Female

4. Ethnicity

- White / Caucasian

- Hispanic or Latinx

- Black or African American

- Native American or American Indian

- Asian / Pacific Islander

- Other

- Multiracial

- Prefer not to answer

5. Age group

- Under 25

- 25-34

- 35-44

- 45-54

- 55-64

- 65-74

- 75 or over

6. What is the highest level of education you have completed?

- Bachelor's degree

- Master's degree

- Professional degree

- Doctorate degree

- Other

7. Have you completed a graduate degree in addition to a Master's degree in library/information science?

- No

- No, but I am in the process of completing an

additional Master's degree

- No, but I am in the process of completing a

professional degree

- No, but I am in the process of completing a

doctoral degree

- Yes, I have an additional Master’s degree

- Yes, I have a professional degree

- Yes, I have a doctoral degree

- Other

8. When did you graduate from library school?

- I did not attend library school

- I am currently in library school

- Within the last year

- 1-3 years ago

- 4-6 years ago

- 7-9 years ago

- 10+ years ago

9. At what kind of institution do you work?

- I am not currently employed

- Community or junior college

- Four-year college

- Master's-granting university

- Doctoral/research university

- Other

10. How long have you worked at your current institution?

- Less than one year

- 1-3 years

- 4-6 years

- 7-9 years

- 10+ years

11. How long has instruction been a part of your work responsibilities?

- Less than one year

- 1-3 years

- 4-6 years

- 7-9 years

- 10+ years

12. What kinds of instruction are part of your work responsibilities?

Select all that apply.

- Face-to-face instruction

- Online instruction

- Blended / hybrid instruction

13. On average, how frequently do you engage in classroom instruction?

Once a year

- 1-3 times a semester

- 4-6 times a semester

- 7-9 times a semester

- 10+ times a semester

14. Think about your professional experiences in teaching—check off any

of the following statements that apply.

- I had an experience that caused me to question

the way I normally teach.

- I had an experience that caused me to question my

ideas about professional roles (Examples of professional roles include the

kinds of instructional responsibilities an academic librarian should take

on.)

- As I questioned my ideas, I realized I no longer

agreed with my some or all of my previous beliefs or role expectations.

- As I questioned my ideas, I realized I still

agreed with some or all of my beliefs or role expectations.

- I realized that other people also questioned

their beliefs about their instructional roles or responsibilities.

- I thought about acting in a different way from my

usual teaching beliefs and roles.

- I felt uncomfortable with professional

expectations (for example, what my job responsibilities or work roles

were) around teaching and instruction.

- I tried out new teaching roles so I would become

more comfortable and confident in them.

- I tried to figure out a way to adopt these new

ways of acting.

- I gathered the information I needed to adopt

these new ways of acting.

- I began to think about the reactions and feedback

from my new professional behavior.

- I took action and

adopted these new ways of acting.

- I do not identify with any of the statements

above.

15. Since you have been providing information literacy instruction, do

you believe you experienced a time when you realized that your values, beliefs,

opinions, or expectations (for example, how you viewed your work

responsibilities or roles as an academic librarian) changed?

- Yes

- No

- I'm not sure

16. Describe what happened when you realized your values, beliefs,

opinions, or expectations about your instructional responsibilities had

changed.

17. Did any of the following individuals influence this change? Check

all that apply.

- Interaction with a student or students

- Support from a colleague

- A challenge from a colleague

- Support from another librarian

- A challenge from another librarian

- Support from a subject area faculty member

- A challenge from a subject area faculty member

- Support from a mentor

- A challenge from a mentor

- Support from a supervisor

- A challenge from a supervisor

- Support from my library/institution’s

administration

- A challenge from my library/institution’s

administration

- Other:

________________________________________________

- No individual influenced my experience of change

18. Did any specific learning experience or resource influence this

change? If so, check all that apply.

- Taking a class or classes in library school

- Taking a class or classes in another graduate

program

- Teaching in a face-to-face course

- Teaching in an online course

- Teaching in a blended/hybrid course

- Observing other academic librarians’

instructional practices

- Receiving feedback from other academic librarians

on your teaching practices

- Observing subject area faculty’s instructional

practices

- Receiving feedback from subject area faculty on

your teaching practices

- Receiving feedback from students who participated

in your instruction

- Completing a self-assessment of your teaching

practices

- Writing about your teaching practices in a

reflection journal or other personal format

- Writing about your teaching practices for

publication

- Attending meetings, workshops, or trainings

within your normal working environment

- Attending professional meetings, conferences, or

workshops outside of your normal working environment

- Participating in online webinars or seminars

- Reviewing guidelines, standards, or other

documents from professional organizations

- Reading scholarly literature on information

literacy instruction

- Reading scholarly literature on the scholarship

of teaching and learning

- Other

________________________________________________

- No experience influenced the change I experienced

19. Did any significant professional event influence the change? If so,

check all that apply.

- Completion of library graduate program

- Completion of other

graduate program

- First professional job after graduate school

- Change of job

- Loss of job

- Change in job responsibility or duties

- Other

________________________________________________

- No professional event influenced the change I

experienced

20. Think back to when you first realized that your views or perspective

had changed. What did your professional life have to do with the experience of

change? [Free response]

21. Would you characterize yourself as someone who usually thinks back

over previous decisions or past behavior?

- Yes

- No

22. Would you characterize yourself as someone who reflects upon the

meaning of your professional experiences for your own purposes?

- Yes

- No

23. Which of the following factors have been a part of your

instructional work as an academic librarian? Please select all that apply.

- Interaction with a student or students

- Support from a colleague

- A challenge from a colleague

- Support from another librarian

- A challenge from another librarian

- Support from a subject area faculty member

- A challenge from a faculty member

- Support from a mentor

- A challenge from a mentor

- Support from a supervisor

- A challenge from a supervisor

- Taking a class or classes in library school

- Taking a class or classes in another graduate

program

- Teaching a face-to-face class session

- Teaching or providing instruction for an online

course

- Observing other academic librarians’

instructional practices

- Receiving feedback from other academic librarians

on your teaching practices

- Observing subject area faculty’s instructional

practices

- Receiving feedback from subject area faculty on

your teaching practices

- Receiving feedback from students who participated

in your instruction

- Completing a self-assessment of your teaching

practices

- Writing about your teaching practices in a

reflection journal or other personal format

- Writing about your teaching practices for

publication

- Attending professional meetings, conferences, or

workshops outside of your normal working environment

- Attending meetings, workshops, or trainings

within your normal working environment

- Participating in online webinars or seminars

- Reviewing guidelines, standards, or other

documents from professional organizations

- Reading the scholarly literature on information

literacy instruction

- Reading the scholarly literature on the

scholarship of teaching and learning

- Other

________________________________________________

- None of these have been factors of my

instructional work as a librarian

Complete this survey

Thank you for completing this survey! Would you be willing to

participate in a virtual follow-up interview? If so, please include your first

and last name as well as an email address where you can be reached during the

summer months.

Name ________________________________________________

Email address ________________________________________________

Individuals who qualify to

participate in the follow-up interviews will be selected at random.

This survey instrument was published in:

Hess, A. N. (2018) Transforming

academic library instruction: Shifting teaching practices to reflect changed

perspectives. Lantham, MD: Rowman &

Littlefield.

King (1997, 2009) retains the copyright to the original Learning

Activities Survey.