Setting

The University of

Calgary is a research-intensive university with 14 faculties offering more than

250 academic programs and serving more than 30,000 students. Libraries and

Cultural Resources (LCR) delivers front line reference services in a variety of

channels (in person, email, chat, and SMS) to students, staff and faculty

through seven physical libraries and via our website, which is powered by

Springshare’s LibApps platform. Library patrons, including faculty, students,

staff, alumni, and members of the community, engage with front line reference

staff to pose a wide variety of questions, including in the complex and

rapidly-changing area of scholarly communication.

Problem

The scholarly

communication ecosystem has been in a period of disruption for a number of

years, leaving both novice and experienced information seekers with unanswered

information needs (Myers, 2016). As defined by the Association of College and

Research Libraries (2006), scholarly communication is “the system through which

research outputs are created, evaluated, disseminated, and preserved” (para.

1). Much of the research literature to date has focused on training librarians

in scholarly communication, even though front line staff may often be the first

point of contact. If these staff have not been provided training to respond

adequately, the quality of the reference interaction may be negatively

impacted.

We were interested in

assessing the frequency with which patrons approached front line staff members

with questions related to scholarly communication and assessing whether or not

staff members had adequate training and support to answer or appropriately

refer these questions. To do this, we implemented a project to collect and

analyze reference transactions before and after a training program. This

allowed us to assess baseline competencies in scholarly communication, as well

as the impact of the training program on reference transactions.

Evidence

Reference

transactions were collected by all library staff members in the LibApps

platform via three channels:

- LibChat chat reference, which recorded

transcripts of chat reference conversations

- Reference Analytics, where staff members

input queries they received at any service point

- Tickets, which recorded email and SMS

inquiries that may be answered or referred

For the project, we

examined anonymized reference transactions collected through all three

channels.

To capture reference

transactions relating to scholarly communication, we searched for a variety of

keywords. The keywords were selected based on content in a document developed

by the Joint Task Force on Librarians’ Competencies in Support of E-Research

and Scholarly Communication (Calarco, Shearer, Schmidt, & Tate, 2016),

which described competencies in four categories:

- Scholarly publishing services

- Open access repository services

- Copyright and open access advice

- Assessment of scholarly resources

The document outlines

competencies in terms of knowledge, understandings, and abilities. We judged

that front line staff members should be able to answer or refer basic questions

in the knowledge categories and

should be able to appropriately refer more complex questions.

We selected 12

keywords: publishing, open access, PRISM

(our institutional repository),

repository, deposit, ORCID, impact, copyright, predatory, host, DOAJ, and Creative Commons. Duplicates,

transactions that were not complete enough to categorize, and irrelevant

results were manually removed.

We analyzed and

compared data between two time periods: (1) September to December 2017, and (2)

September to December 2018. We sought to eliminate potential differences

between fall and winter terms by comparing two fall term periods. The staff

training sessions were held between the two time periods, in summer 2018.

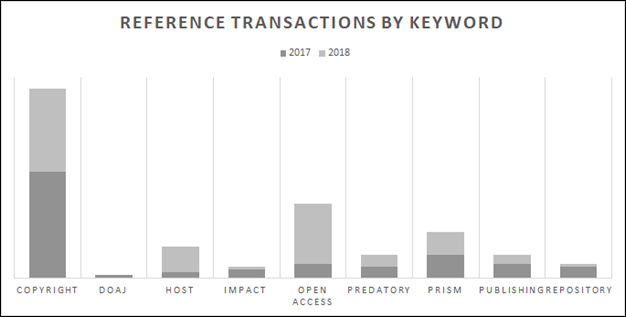

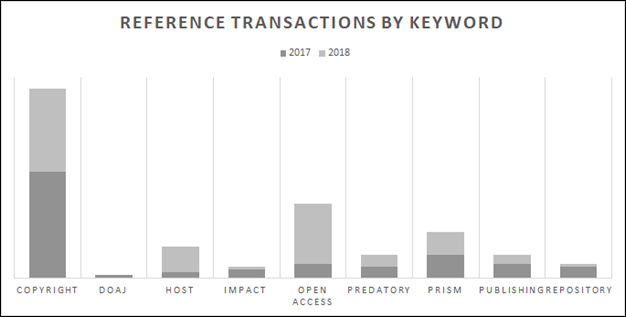

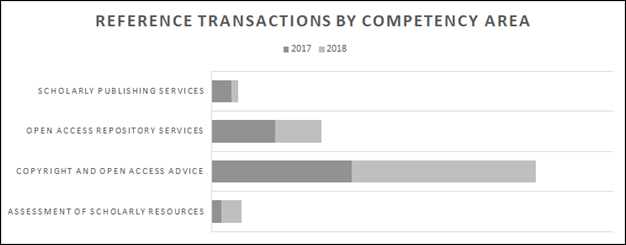

Data from 2017—the

period before training—revealed 70 unique reference transactions. Questions including the keyword copyright were by far the most common

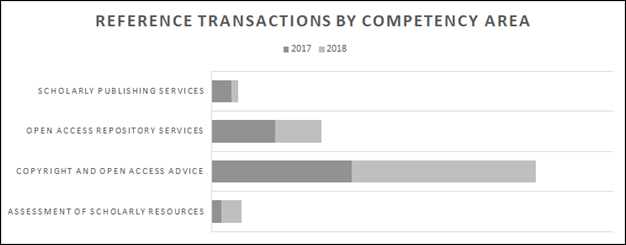

(Figure 1), and Copyright and Open Access Advice was the most common category

as defined by the Joint Task Force profile (Figure 2). Some keywords garnered

no results (deposit, ORCID, Creative

Commons). Questions on open access

were second most frequent, while questions about the institutional repository, PRISM, were third most frequent.

The range of

questions was broad. Questions in the Copyright and Open Access Advice

competency area included course reserve inquiries, use of third party materials

(particularly images) in teaching and learning resources, fair dealing,

scholarly sharing, and requests for advice around open access publishing.

Transactions in the Open Access Repository Services category included a large

number of questions about access to electronic resources for alumni or

community members, as well as questions about both the University of Calgary’s

institutional repository, PRISM, and third party scholarly sharing sites.

We found that the

vast majority of questions were either answered or referred adequately. In the

2017 time period, 96% (n=67/70) of questions were deemed successfully answered

or referred.

Implementation

Due to the diverse

and fluid nature of scholarly communication topics, and because LCR did not

have any internal training opportunities for current staff, the authors

developed a training program. The training program involved two key components:

Website Updates and Improvements

Libraries and

Cultural Resources (LCR) used frequently asked questions (FAQs) through the

SpringShare platform to both answer queries and direct patrons to more detailed

information resources such as research guides. These were popular tools for

both patrons and reference staff. In the spring and summer of 2018, we

identified, reviewed, and updated or created new FAQs relating to scholarly

communication. Topics included predatory publishers, bibliometrics, embargoes

in the institutional repository, tools to legally access open access literature

(e.g., browser extensions), and assessing the copyright status of digital

images found online for use in teaching and learning. These topics reflected

questions that were found in the initial assessment of reference transactions

and were not adequately answered by current website content. We promoted

library staff awareness of the scholarly communication FAQs during the training

sessions and using email and word of mouth to maximize impact.

Training Sessions

Two interactive

one-hour training sessions were designed and delivered to library staff members

to promote knowledge and awareness of common scholarly communication questions.

The content for the sessions was based on the Joint Task Force on Librarians’

Competencies in Support of E-Research and Scholarly Communication. Our aim in

designing the sessions was to ensure that front line staff members would have

the capacity to correctly answer or refer queries in the knowledge categories in all four of the scholarly communication

categories as defined by the Joint Task Force document. The sessions included

training regarding when to refer more complex questions. Training sessions were

structured in a series of scenarios, which small groups attempted to resolve

and then discussed with the larger group. These were adapted from scenarios

developed by the COPPUL Scholarly Communication working group (2018).

In total, 15 library

staff members attended the two interactive training sessions. Staff members

represented a mix of academic and support staff. No formal assessment of these

sessions was done but participants noted that the sessions were useful and that

they planned to reuse the scenarios in their own teaching and reference

practice.

Outcome

Data from 2018—which

represented the time period after training—contained 76 unique reference

transactions, representing an increase of 9% between time periods. Generally,

the categories of questions being asked were similar between the two time

periods, although questions relating to open

access showed a dramatic increase from 0.0 to 28% of total questions

between time periods. This is likely due to a change in LCR’s Open Access

Authors Fund which occurred in October 2018.

Figure 1

Frequency of transactions based on keywords

present in reference transactions.

Figure 2

Frequency of interaction based on COAR Task

Force Profile.

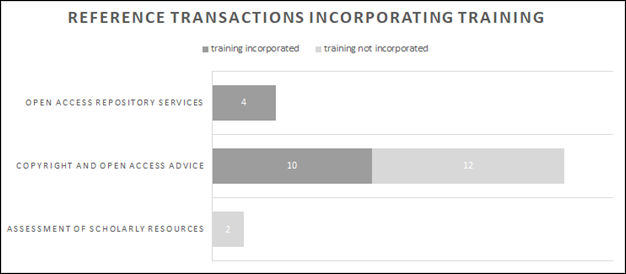

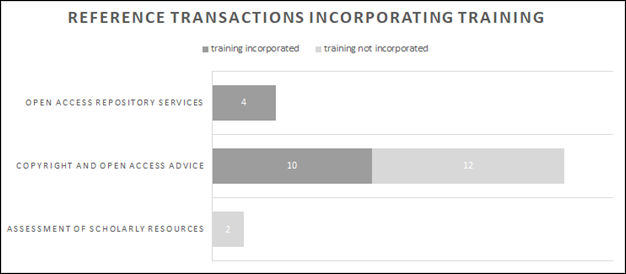

Figure 3

Reference transactions from the 2018 period

that incorporated training materials.

In the 2018 data, 97%

(n=71/73) questions were successfully answered or referred, representing a 1%

increase from the 2017 period. Additionally, there were 28 reference questions

that directly addressed topics covered in the training. Based on our analysis,

half (n=14) of these transactions referenced the training in some way, either

by directing patrons to a website FAQ, or rephrasing content from the training

in a direct response (Figure 3).

Reflection

The primary goal of

this project was to target the skill development of front-line academic library

staff members. It was also important to make use of data that staff members

collected daily and use it for evidence based training and quality improvement.

Using three

communications channels to collect data on scholarly communication transactions

proved to be successful and provided a broad overview of the types of

interactions the library received through chat, in person, email, or other. A

weakness of the data was that it likely did not reflect all interactions.

Although most LCR staff were encouraged to record all transactions, there may

have been transactions that were not entered, and some specialized staff (e.g.,

those in the Copyright Office) did not follow this workflow. Additionally,

Reference Analytics transactions that staff members manually entered were

sometimes lacking details, making them impossible to categorize.

Training initiatives

were well-received and appear to have had an impact on competencies. However,

the number of transactions captured in the second time period specifically

related to training was small (n=28). Of these, half showed evidence of

training effects. More frequent training opportunities, and more outreach and

engagement with front-line support staff would be beneficial. The combination

of online tools and interactive in-person workshops were well-received by

library staff but offering more options and on a more regular basis would be

beneficial. The model employed at East Carolina University provided a useful

template for such initiatives (Shirkey, Hoover, & Webb, 2019).

Two resources were

invaluable for structuring this project. The profile developed by the Joint

Task Force on Librarians’ Competencies in Support of E-Research and Scholarly

Communication (2016) provided scholarly communication categories and

competencies. Secondly, the training scenarios developed by the COPPUL

Scholarly Communications Working Group (2018) provided compelling interactive

scenarios for staff to engage and discuss key concepts and challenging questions

in scholarly communication. Incorporating both resources added to the success

of the project.

Conclusion

Trends and

developments in issues of copyright, open access, predatory publishing, and

other realms of scholarly communication are continuing to unfold. Scholars and

students often look to the library to stay current and compliant with

regulatory changes and best practices. As the first point of contact for many

of these queries, it is essential to ensure library staff are well-equipped to respond

and direct patrons toward success. Using evidence from routinely-collected

library data can assist libraries in continually improving their reference

services.

References

Association of College and Research

Libraries. (2006). Principles and strategies

for the reform of scholarly communication 1. Retrieved from http://www.ala.org/acrl/publications/whitepapers/principlesstrategies

Calarco, P., Shearer, K., Schmidt, B., & Tate, D. (2016,

June). Librarians’ competencies profile for

scholarly communication and open access. Retrieved from https://www.coar-repositories.org/files/Competencies-for-ScholComm-and-OA_June-2016.pdf

COPPUL Scholarly Communications Working

Group. (2018). Talking to faculty and students about open access. Retrieved

from https://coppulscwg.files.wordpress.com/2018/05/talking-to-faculty-students-about-open-access-1.pdf

Myers, K. L. (2016). Libraries’ response to

scholarly communication in the digital era. Endnotes: The Journal of the New

Members Round Table 7(1), p.13-20. Retrieved from http://www.ala.org/rt/sites/ala.org.rt/files/content/oversightgroups/comm/schres/endnotesvol7no1/Article_Scholarly_Communication.pdf

Shirkey, C., Hoover, J., & Webb, K.

(2019). Establishing a scholarly

communication baseline using liaison competencies to design scholarly

communication boot camp training sessions. Retrieved from http://thescholarship.ecu.edu/handle/10342/7015

![]() 2019 Hurrell

and Murphy. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the

Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

2019 Hurrell

and Murphy. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the

Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.