Setting

The

Eberly Family Special Collections Library is located on the University Park

campus of Pennsylvania State University. Housing over 200,000 printed volumes,

the Special Collections Library serves a range of researchers, including

undergraduate and graduate students, professors, and community members.

In

the past, the Special Collections Library was three distinct units: the Rare Books Room, Historical Collections and Labor

Archives, and the Penn State Room (later called University Archives) (Penn

State University Libraries, n.d.). The three units were brought together

administratively in the 1970s, and moved into a shared physical space in 1999.

Although all materials are delivered to patrons through one service point,

behind the scenes, materials remain organized in these three historic units.

Problem

Legacy

practices for assigning home locations have led to retrieval problems. The

Special Collections Library uses nearly 100 home locations. For example, within

Rare Books, artists' books are shelved together in a "Fine Printing"

home location, while books in the utopia collection are assigned the

"Utopia" home location. Some of these are then further subdivided

into sub-locations. "Fine Printing," for example, is divided by

publisher, so that all books published by Bird & Bull are shelved in one

location, books published by Compagnie Typographique

in another, and so forth. In total, 19 publishers had established Fine Printing

sub-locations. To add to this confusion, some sub-locations are actually located

in different physical areas. The Allison-Shelley Collection, named for a donor,

is shelved partially in the Special Collections stacks, and partially in a

named room on a different floor. Both are assigned the

"Allison-Shelley" home location. Only sub-location indicates which

item is where.

This

arrangement allows curators, instruction librarians, and exhibition planners to

quickly locate materials, but is not intuitive for the reference staff who

retrieve and shelve items. As a result, item retrieval was frequently time

consuming, causing patrons to wait while staff looked for their item.

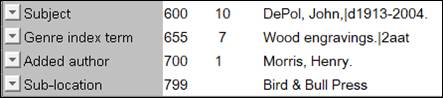

Prior

to this project, cataloguers recorded sub-location in a public note in the item

record, which presented several problems. First, while public notes display in

the online catalogue, they do not print on retrieval slips or call number

labels. In addition, text in this field is not searchable, making it impossible

to generate accurate shelflists for sub-locations.

Finally, if Penn State were to migrate to a new library system, there is no

guarantee that these notes would transfer.

We

needed to devise a new approach for recording sub-location information. We

needed the new approach to allow printing on retrieval slips to make the item's

location clear to staff and decrease retrieval time. Staff needed to be able to

search sub-location to generate accurate shelflists.

Finally, it needed to be protected in the event of future migration.

While

the easiest approach would have been to create separate home locations, due to

the large number already established, our systems librarians preferred we find

another option. Instead, we elected to implement a new, locally-defined MARC

field, MARC field 799, to capture sub-location information. Adding the field to

the catalogue was a simple matter of defining a new policy in our ILS.

Populating the field with sub-location information, however, was more involved.

In total, we identified 5 home locations with sub-location information we

needed to record in the 799 field, totaling 63 sub-locations and over 6,500

items. Adding this information by hand would have been time-consuming and

risked introducing human error.

Evidence

To

gather sub-location information, we decided to use analytics software. Ben

Showers defines "analytics" as the "discovery and communication of meaningful patterns in data" and

"analyzing data to uncover information and knowledge (discovery) and using

these insights to make recommendations (communication) for specific actions or

interventions" (p. xxx, emphasis in original). Analytics

reports would allow us to generate lists of all public and internal notes, find

patterns, and spot variations.

Penn

State University uses BLUEcloud Analytics from SirsiDynix. We generated a report to retrieve public and

internal notes from item records for the five collections with sub-locations.

The report output included: title control number, title, author, barcode, call

number, home location, internal notes, and public notes.

Figure

1

Sub-location

recorded in a public note field.

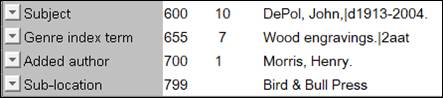

Figure

2

Bibliographic

record with MARC field 799 inserted.

After

running the analytics report for each home location, we exported it to a CSV

file. A few problems became immediately apparent. First, while we had expected

to see sub-location information recorded in public notes, we learned that this

information was also recorded in internal notes. The Fine Printing collection,

for example, contained 2,743 items. Of these, 379 items had a public note,

where 1,018 had an internal note, showing that the internal note was actually

used more frequently than the public note. Second, while many of these notes

recorded sub-location, some recorded other information, such as limitation

statements or binding notes. Finally, we found numerous variations in name form

for some sub-locations. For example, "Children's Literature" was

recorded variously as "C.L.," "Child. Lit.,"

"Children's Lit.," and so forth, totaling over 20 variations.

Using

OpenRefine (http://openrefine.org/), an open

source tool for cleaning data, we separated this information into different

columns, isolating the sub-location information. Following this, we used OpenRefine again to normalize location names. Using OpenRefine, we were able to edit all identical cells, so

variants were quickly updated to the full name form for each sub-location.

Implementation

After

successfully isolating sub-location information and normalizing name forms, we

needed to push this information into bibliographic records. Using the item

information from the analytics report, our Digital Access Team successfully

pushed MARC 799 fields into the appropriate bibliographic records, successfully

updating all 6,500 records across 5 home locations. Moving forward, cataloguers

will add this information directly to the 799 field rather than using the note

fields. In addition, since we had discovered all the variations in names for

sub-location, we were able to normalize and document name forms, ensuring that

cataloguers will enter the correct form in the future.

Outcome

Implementing

the MARC 799 field for sub-location had some immediate impacts. First, we were

able to map the MARC 799 field to our Aeon retrieval system. Sub-location

information now prints on retrieval slips, which enables faster and more

accurate retrieval and re-shelving of these items.

Adding

sub-locations in the MARC 799 also allows us to generate shelflist

reports reflecting actual shelving order. Now, we can simply search for records

with a given sub-location name in the 799 field and sort the results in call

number order. Staff can perform shelf-reading more easily, which in turn

improves collection maintenance and security.

In

addition, as sub-location data is now in the bibliographic record rather than

the item record, it is more visible and protected in the event of future

migration. This has become an even more pressing issue as Penn State University

is preparing to implement a new catalogue discovery layer, in which public

notes will no longer be visible.

Reflection

Our

chief obstacle in this process was gathering data from BLUEcloud

Analytics. BLUEcloud relies heavily on pre-packaged

reports, and none of the reports available provided the information we needed.

We worked closely with our local BLUEcloud Analytics

expert team to write and test the report, making changes as needed to ensure we

captured all of the note fields, along with item information to update records

later.

The

rest of the process was relatively straightforward. In addition, since the

report has already been written, it's now available for use to other local BLUEcloud Analytics users, and we won't have to repeat

creating this report in the future.

However,

while the addition of the MARC field 799 fulfilled the immediate project goals,

the larger problem of having 100 home locations remains. Moving forward, we

hope to address this, potentially condensing home locations to a smaller

number. When (and if) we do this, the 799 fields may be obviated, but it could

be several years before we take this step. In the meantime, the sub-location

information in the 799 field will play a valuable role in retrieval and

collection maintenance. If we do later decide to condense our home locations,

the shelflist reports made using the 799 fields will

be invaluable for ensuring accurate interfiling of materials.

Conclusion

Analytics

are a powerful tool for finding patterns in catalogue data and targeting

records to edit. Using analytics allowed us to fulfill our project goals by

getting a list of every sub-location recorded in a note, normalizing

sub-location name, and pushing the MARC 799 into targeted records. We completed

this work quickly and accurately, and in a fraction of the time that we would

have required to do this work manually. Running an analytics report has become

standard anytime we need to update catalogue information on a large scale.

Subsequently, we have used analytics reports for updating call numbers,

maintaining genre headings, and updating home locations following collection

moves.

References

A short history

of Penn State Special Collections. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://libraries.psu.edu/about/libraries/special-collections-library/short-history-penn-state-special-collections.

Showers, B.

(Ed.). (2015). Library analytics and

metrics: Using data to drive decisions and services. London: Facet

Publishing.

![]() 2019 Hobart.

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative

Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License

4.0 International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

2019 Hobart.

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative

Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License

4.0 International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.