Research Article

Evaluation of Integrated

Library System (ILS) Use in University Libraries in Nigeria: An Empirical Study

of Adoption, Performance, Achievements, and Shortcomings

Saturday U. Omeluzor, Ph.D.

Systems Librarian

Library Department

Federal University of

Petroleum Resources Effurun

Delta State, Nigeria.

Email: omeluzor.saturday@fupre.edu.ng

Received: 8 July 2019 Accepted: 2 Oct. 2020

![]() 2020 Omeluzor. This

is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

2020 Omeluzor. This

is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

DOI: 10.18438/eblip29604

Abstract

Objective - The aim of this study was to evaluate Integrated Library System (ILS)

use in university libraries in Nigeria in terms of their adoption, performance,

achievements, and shortcomings and to propose a rigorous model for ongoing

evaluation based on use of candidate variables (CVs) derived from the approach

used by Hamilton and Chervany (1981) and from

evaluation criteria suggested by Farajpahlou (1999,

2002).

Methods - The

study adopted a descriptive survey design. Nigeria is made up of six

geo-political zones including: North-East (NE), North-West (NW), North-Central

(NC), South-South (SS), South-East (SE), and South-West (SW). The population

for this study comprised Systems/IT and E-librarians in the university

libraries from all six of the geo-political zones of Nigeria. Because of the

large number of universities in each of the zones in Nigeria, a convenience

sampling method was used to select six universities representing federal,

state, and private institutions from each of the six geo-political zones of

Nigeria. A purposive sampling method was used to select the Systems/IT and

E-librarians who were directly in charge of ILS in their various libraries.

Therefore, the sample for this study was made up of 36 Systems/IT and

E-librarians from the 36 selected universities in Nigeria. The instrument used

to elicit responses from the respondents was an online questionnaire and was

distributed through the respondents’ email boxes and WhatsApp. The

questionnaire administration received a 100% response rate.

Results -

Findings revealed that university libraries in Nigeria have made remarkable

progress in the adoption and use of ILS for library services. The findings also

showed that much has been achieved in the use of ILS in library services.

Evidence in the study indicated that the performance of the ILS adopted in the

selected university libraries in the area of data entry and currency, accuracy,

reliability, completeness, flexibility, ease of use, and timeliness was

encouraging.

Conclusions - Adoption and use of ILS in libraries is changing the

way libraries deliver services to their patrons. Traditional methods of service

delivery are different from the expectations of the 21st century

library patrons. The transformation seen in the university libraries in Nigeria

using ILS was tremendous and is changing the narratives of the past. However,

several shortcomings still exist in the adoption and use of ILS in university

libraries in Nigeria. Overcoming some of the limitations would require a

conscious effort and decisiveness to ensure that librarians and library patrons

enjoy the best services that ILS can offer. ILS developers should consider the

dynamic needs of libraries and their patrons and incorporate specific candidate

variables (CVs) in their ILS designs to enhance the quality of the services

being offered to the library patrons.

Introduction

“Library and information science occupies a vantage position in the educational sector and

plays a strategic role in national growth and development” (Shekarau, 2014).

University libraries today are adopting Information and Communication

Technologies (ICTs) to deliver information to their patrons. ICTs are playing a

pivotal role in the way and manner in which information is being handled in the

library. Before the use of ICT tools in libraries, traditional methods were

employed to deliver most library services. Traditional library processes have

been judged as unable to respond quickly enough in a technologically driven

environment (Ayiah & Kumah,

2011). With a steady growth in library collections for various programs that

are offered in the university, and the decentralization of library activities,

it is essential to use an integrated library system that responds quickly to

the needs of librarians and library patrons (Omeluzor,

Adara, Madukoma, Bamidele

& Umahi, 2012).

An

ILS has been defined as “a series of

interconnected operations that streamline input and retrieval of information

for both information professionals and researchers” (Lucidea.com, n.d.). Since

the concept of an ILS was first introduced by Harder in 1936, it has been

developed and modified to suit different ideas and purposes in different

sectors of the economy, for example, banking, marketing, and aviation among

others. In the library, the term ILS has been used interchangeably for both

mechanization and automation (Riaz, 1992). Singh (2013) defined library automation as the

computerization of library records and functions, using computer hardware and

software for tasks that may require a lot of paperwork and staff time. Singh

(2013) noted that ILS is the use of computers, and associated technology, to do

exactly what has been traditionally done in libraries with the justification of

reducing cost or increasing performance. ILS enables adequate monitoring,

controlling, service delivery, access to bibliographic records, collaboration

among libraries, and enhanced access to information materials irrespective of patrons’

geographical locations (Omeluzor & Oyovwe-Tinuoye, 2016).

University libraries

in Nigeria and other countries have increasingly used new tools such as ILS and

methods for delivering information services to their patrons since the

beginning of the 21st century (Sharma, 2009; Oladokun & Kolawole, 2018).

However, in spite of the advances made in ILS adoption by Nigeria libraries, Ani

(2007), Aguolu and Aguolu (2006) argued that libraries in

Nigeria have been slow to adopt this level of automation and that most academic

and research libraries in Nigeria had not computerized any of their functions.

Studies such as Osaniyi (2010) and Omeluzor, et al.

(2012) have also shown that some of the ILS adopted in Nigeria libraries are

not performing optimally, impacting negatively on the libraries’ achievements.

It is against this backdrop that it becomes crucial to evaluate ILS adoption, performance, achievements, and shortcomings in

Nigeria university libraries.

Although there have been many studies conducted that identify

issues related to ILS in Nigeria university libraries, none have used a

rigorous model for the evaluation. The use of appropriate candidate variables

(CVs) and evaluation

criteria may provide evidence of the performance of

ILS that could support the decision for its adoption in library services. This

study focusing on ILS adoption, performance, achievements, and shortcomings

adapted Hamilton and Chervany’s (1981) CVs approach

to identify the performance features of ILS used in Nigeria university

libraries.

Background

The use of ILS to automate or streamline library

management, processes, and services is not a new phenomenon in developed

countries. In developing countries, and especially Nigeria, ILS is gradually

gaining momentum but not without some shortcomings. Over the last decade, a

considerable number of ILS have been developed and deployed in libraries to

facilitate easier access to information. In Nigeria, efforts were made to adopt

and use ILS in library services. Since the 1990s, when the World Bank in 1990

deployed management information system in some selected federal universities to

improve institutional capacities of Nigeria universities, a considerable number

of ILS have been developed and deployed in Nigeria university libraries to ease

access to information. The intervention by the World Bank to deploy management

information system included the deployment of unified ILS known as TINLIB for

library automation. In addition, some federal university libraries in Nigeria,

such as the University of Ibadan and University of Nigeria Nsukka Enugu Centre,

among others, had adopted CD/ISIS, X-LIB, LIB+, GLASS, and Alice for Windows to

provide library services. Similarly, several private university libraries have

also adopted ILS for library services. For example, Bowen University, Iwo

(BUI), and Babcock University (BU) libraries had at different times adopted

Koha ILS for library services.

University libraries in Nigeria have adopted both

proprietary and open source ILS. Proprietary ILS products have been available

for many years and are characterized by expensive customized coding; these

products have remained the dominant approach used for library automation (Uzomba et al,

2015). In contrast to proprietary ILS products, open source software (OSS) ILS

products provide the original source code used in creating it, as well as the

right of redistribution, which provides users the freedom to modify and

customize them in order to suit one’s own purposes. Conversely, a closed

proprietary system limits the way the library can access the underlying data

(Breeding, 2009). OSS is freely developed for the enhancement of routine

library activities. OSS is available for anyone to have; not only is the

software free, but it is also free for anyone to run, copy, distribute, study, change,

improve, modify, and share for any purpose, thus enabling libraries to have

greater control over their working environments (Kumar & Jasimudeen, 2012). Whether the libraries have adopted

either proprietary or open source ILS in Nigeria university libraries, there is

evidence in the literature that challenges facing the adoption of ILS in

Nigeria university libraries abound. However, few if any studies have focused

on the adoption, achievements, performance, and shortcomings of ILS, which this

present study tries to accomplish. The researcher believes that this study will

contribute in developing a model for the evaluation of the adoption,

achievements, performance, and shortcomings of ILS using the already proposed

model by Hamilton and Chervany (1981) together with Farajpahlou’s (1999, 2002) evaluation criteria for the

evaluation of ILS in university libraries across the world. There are already

numerous studies on the prospects, performance, successes and challenges of ILS

adoption and use in university libraries, especially in developing nations (Osaniyi, 2010; Omeluzor,

et al, 2012; Breeding, 2009; Uzomba, et al, 2015; Atua-Ntow, 2016). However, none of these studies have

revealed the use of Hamilton and Chervany (1981) CVs to

evaluate the capability of ILS in library services.

Aims

This study is aimed at designing a model that would be

fundamental for evaluating the adoption, performance, achievements, and

shortcomings of ILS in university libraries. It is guided by the following

objectives, to:

1. Evaluate the extent of ILS adoption in Nigeria

university libraries.

2. Evaluate the achievements made so far with ILS in

Nigeria university libraries.

3. Evaluate the performance of ILS in library services in

Nigeria university libraries.

4. Evaluate the shortcomings of ILS in Nigeria university

libraries.

Literature

Review

Evaluating ILS in Nigeria University Libraries

Hamilton and Chervany (1981)

proposed an approach for the evaluation of management information systems (MIS)

that involved the use of candidate variables (CVs) such as: data currency,

accuracy, reliability and completeness, system flexibility, ease of use,

response time, and turnaround time. Farajpahlou

(1999) proposed the use of specific criteria for assessing the success of ILS.

These criteria were in four broad categories including: management of the

system, usage of the system, technicalities of the system, and boundary issues.

Each of the criteria is found to be useful in this present study as together

they present the basis for identifying the achievements, performance, and

shortcomings of ILS in university libraries. Farajpahlou

(2002) further emphasized that a successful automated library system would

require pre-conditions such as a well-prepared automation plan and

implementation program. Consistent evaluation of ILS is important to identify

areas of improvement for effective services. Hill and Patterson (2013) noted

that assessment could present challenges but is still worthwhile to undertake

if the aim is to create and add value to that which is being assessed.

Similarly, Okpokwasili and Blakes (2014) believe that

assessments of ILS, library services, and resources need to be carried out on a

continuous basis to ensure that they remain relevant to the needs of their

patrons and stakeholders.

Omeluzor and Oyovwe-Tinuoye (2016) assessed the

adoption and use of ILS for library services in university libraries in Edo and

Delta States. A section of the instrument used for the study elicited

information on the use, achievement, effectiveness, and challenges

of ILS in academic libraries in the two states. Findings in the study revealed

that the automation software adopted in some of the university libraries were

effective for accessing books, journals, and other library materials, as well

as for bibliographic search and retrieval. Although the study presented some

issues about use, achievement, effectiveness, and challenges, it did not focus

on Hamilton and Chervany’s

(1981) CVs or Farajpahlou’s (1999, 2002) criteria,

which is a gap that this present study tries to bridge. Some studies (Akpokodje & Akpokodje, 2015; Ojedokun, Olla & Adigun, 2016) have shown one or two of

the variables, such as adoption, achievements, performance or shortcomings.

Surprisingly, none of these studies has tried to integrate Hamilton and Chervany’s (1981) CVs which could have provided a clearer

view of the performance and perhaps records of achievements and shortcomings of

ILS in library services. A deliberate study, with a focus on CVs, could reveal

some underlying attributes of ILS and the reasons for its adoption in library

services.

Adoption of ILS in Nigeria University Libraries

Libraries in Nigeria have had their share of problems

in the adoption of ILS. For example, the World Bank in collaboration with the

National Universities Commission (NUC) in 1990 supported 20 federal

universities in Nigeria with TINLIB automation software among other ICT tools

for 20 participating libraries. The effort did not yield expected results since

Sani and Tiamiyu (2005) in their evaluation of

automated services in Nigerian universities found that the system fell short of

some of the evaluation criteria and CVs proposed by Hamilton and Chervany (1981) and Farajpahlou

(1999, 2002). Sani and Tiamiyu (2005) observed that

the state of automated library services in the universities that were visited

was haphazard, with the situation in state and private universities being

particularly pathetic. This scenario may not be unconnected to lack of

evaluation on the achievements, performance, and shortcomings of the ILS before

adoption. Some laudable initiatives in the adoption of ILS for library services

in Nigeria have failed in the last two decades due to lack of evaluation (Okiy, 1998; Nok, 2006; Osaniyi, 2010; Adegbore, 2010; Omeluzor et al., 2012;

Mbakwe & Ibegbulam,

2014). Aguolu,

et al. (2006) reported the non-computerization of library functions in Nigeria

university libraries. A study by Oladokun and

Kolawole (2018) revealed that 35 libraries across the six geo-political zones

of Nigeria had adopted Koha open source software. Findings in that study

revealed that 13 (36%) of the respondents indicated lack of support from their

institutions as a major reason for non-adoption of Koha in their libraries.

Shortcomings of ILS in Nigeria University Libraries

On the shortcomings of ILS in Nigeria university

libraries, most of the studies focus on the challenges of the automation

process, such as: technical problems, problems with retrospective conversion,

non-availability of the software and vendors’ attitudes, inadequate funding,

lack of skill, inadequate ICT facilities, power supply, and others (Agboola, 2000; Sani & Tiamiyu,

2005; Osaniyi, 2010; Omeluzor, et

al., 2012; Mbakwe

& Ibegbula, 2014). No single research study has

been conducted showing a step by step approach on the evaluation, performance,

achievement, and shortcomings of ILS as portrayed in Figure 1, which perhaps

would have shown evidence and criteria for its adoption in libraries. The

pitfalls of adopting one ILS and switching over to another could perhaps be

avoided if libraries adopt Hamilton and Chervany’s CV

(1981) and even Farajpahlou’s (1999, 2002) evaluation

criteria before adoption of ILS.

The model in Figure 1 proposes the evaluation of the

performance, achievement, and shortcomings of ILS before adoption. The model is

an expansion of Hamilton and Chervany CVs who in 1981

proposed evaluating only performance and achievement of MIS, including:

accuracy, reliability, completeness, flexibility, ease of use, and timeliness

excluding shortcomings. Emphasis in the model proposed by Hamilton and Chervany (1981) is primarily on the performance of information

systems in the delivery of services. An evaluation of the shortcomings of ILS

as part of evaluation criteria would provide insights, helpful when making

decisions about the adoption of ILS in university libraries in the future.

Figure

1

A

model for the evaluation of ILS in a university library

Methods

Research

Approach

The study adopted a descriptive survey design. The

adoption of descriptive survey design provides the researcher the opportunity

of using data collected for this study for ILS evaluation using CVs in Nigeria

University Libraries. According to Nworgu (2006) a descriptive survey design describes a

condition or phenomenon as it exists naturally without manipulation.

Population

Nigeria is made up of six geo-political zones

including: North-East (NE), North-West (NW), North-Central (NC), South-South

(SS), South-East (SE), and South-West (SW). The population of this study

comprised Systems/IT and E-librarians in the university libraries from all six

geo-political zones of Nigeria. Since the aim of this study was to evaluate

ILS, a purposive sampling method was used to select the Systems/IT and

E-librarians who are directly in-charge of ILS in their respective libraries.

Because of the large number of universities in each of the zones in Nigeria, a

convenience sampling method was used to select six universities, comprised of

federal, state, and private universities, from each of the six geo-political

zones of Nigeria, offering a good representative sample to achieve the purpose

of this study. Therefore, the sample for this study is made up of 36 Systems/IT

and E-librarians from the 36 selected universities in Nigeria as shown in Table

1.

Research

Instrument Development

Based on the theoretical framework identified in the

previous studies described above, the researcher developed a structured online

questionnaire using a Google Online Form with five sections (see Appendix A) to provide answers to

the questions raised on the evaluation of the adoption, performance,

achievements, and shortcomings of ILS in Nigeria university libraries. Sections

3 and 5 of the instrument were adopted from Omeluzor et al. (2012) and Omeluzor

& Oyovwe-Tinuoye (2016). The study by Omeluzor et al. (2012) reported the implementation of Koha

ILS at Babcock University Library and the elements adopted are those that

reveal the achievements that were made with ILS such as: “provide on-the-spot

access to resources,” “enable sharing of resources with other libraries,”

“enable online cataloguing” and “provide access to books and external sources”

(p. 218) that are relevant in this present study. On the other hand, Omeluzor and Oyovwe-Tinuoye

(2016) assessed the adoption and use of ILS in academic libraries in Edo State

and Delta State, Nigeria. The elements adopted from that study are those that

show the shortcomings of adopting ILS such as: “inadequate training and

technical knowhow for librarians,” “cost of implementation,” and “inadequate

skilled personnel”. The elements presented in both studies are limited to one

private university library and academic libraries in Edo and Delta States.

Using those elements in this present study provides more insight on how they

affect the overall achievement and performance on the varied ILS adopted in

Nigeria university libraries.

Section 4 of the instrument was adopted from Hamilton

and Chervany (1981) CVs. The researcher found the CVs

proposed in Hamilton and Chervany (1981) for the

evaluation of MIS to be relevant in this present study, as it reveals the

variables that should be considered for inclusion in the evaluation of ILS in

the university library. The CVs that were identified from previous research

studies as being relevant to the evaluation of ILS in library settings are:

data entry and currency, accuracy, reliability, completeness, flexibility, ease

of use, and timeliness. A 4-scale measuring instrument was used for sections 4

and 5 with 4 being the highest and 1 being the lowest.

Distribution and

Data Collection

Before the administration of the questionnaire to the

intended respondents, a pre-test was conducted to assess the reliability of the

instrument on ten Systems/IT and E-Librarians working in public libraries, who

were not part of the study. The 10 responses were retrieved and analysed using

Cronbach Alpha correlation co-efficient at 0.50 level of acceptance which gave

a result of r =0.85. This indicates that the instrument is reliable and

appropriate for data collection for this study since the test result is above

the acceptance point of 0.50. Furthermore, the instrument was also examined by

an ILS researcher to ensure content and construct validity. The questionnaire

was then emailed to some of the respondents. Emailing the respondents directly

eliminated the possibility of receiving responses from unintended respondents.

However, because the researcher could not access all the respondents via email,

the use of Nigeria Library Association (NLA) Online Forum, NLA IT Section and

WhatsApp group became unavoidable. The use of the platforms was found by the

researcher as an alternative to contact those respondents that could not be

reached, since all of them are registered members. The responses received

through those platforms were carefully sifted to eliminate double response from

those respondents that were earlier contacted via email as well as from

non-systems librarians. The Google response page was also very helpful in

catching duplicate responses or any two respondents from the same university.

The use of those platforms helped the researcher receive 100% of the responses

needed to reach the goals of this study. The instrument elicited information on

the ILS adopted, its achievements, performance level, and shortcomings. Data

collected were analyzed using Statistical Package for

Social Sciences (SPSS) version 7.0 and results are presented in frequency

table, mean, standard deviation, chart, and percentage for clarity and

understanding. In Tables 2 and 3 the mean scores are rated as follows: Mean is

0.1 to 1.9 = very low, 2.0 to 2.4 = low, 2.5 to 2.9 = high, 3.0 and above = very

high.

Results

Demographic

Information of the Respondents

Results show that 47% of the respondents with the role

of Systems/IT and E-Librarians in university libraries in Nigeria are female

and 53% are male. The majority of the respondents (48%) have worked between

6-10 years. Another 24% of the respondents have worked between 1-5 years, and

20% of the respondents have worked between 11-15 years. Results also shows that

a low percentage (8%) of the respondents have worked for 16 years or longer.

Table

1a

State of ILS Adoption in

University Libraries

|

University |

ILS currently in use |

ILS

earlier used |

|

Federal |

Koha |

Alice for Windows |

|

Federal |

Koha |

VITRUAL |

|

Federal |

Koha |

|

|

Federal |

Koha |

Alexandria |

|

Federal |

Strategic Library Automation (SLAM) |

|

|

Federal |

CDS ISIS |

|

|

Federal |

Koha |

|

|

Federal |

VIRTUA |

|

|

Federal |

Koha |

|

|

Federal |

New

Gen Lib |

SLAM |

|

Federal |

Readable

|

VIRTUAL, Alice for

Windows |

|

Federal |

Koha |

Alice for Windows |

|

Federal |

|

VIRTUAL |

|

Federal |

New

Gen Lib |

Millennium |

|

Federal |

Koha |

GLASS, LIB+ |

|

Federal |

Koha |

VIRTUAL |

|

State

|

SLAM |

|

|

State |

|

|

|

State |

Koha |

|

|

State |

Koha |

X-Lib, SLAM |

|

State |

|

|

|

State |

Senayan LMS |

SLAM |

|

State |

|

|

|

State |

Koha |

|

|

State |

SLAM |

|

|

State |

Alice

for Windows |

|

|

State |

Koha |

|

|

State |

Koha |

|

|

State |

|

|

|

Private |

Greenstone |

|

|

Private |

Koha |

X-Lib |

|

Private |

New

Gen Lib |

|

|

Private |

Koha |

|

|

Private |

Millennium |

|

|

Private |

Koha |

|

|

Private

|

Koha |

|

Table 1b

Type

of ILS Used Earlier and Currently in Use in the Selected University Libraries

|

University |

ILS currently in use |

ILS used earlier |

||

|

Open source ILS |

Proprietary |

Open source ILS |

Proprietary |

|

|

Federal |

Koha |

|

|

Alice for Windows |

|

Federal |

Koha |

|

|

VITRUAL |

|

Federal |

Koha |

|

|

|

|

Federal |

Koha |

|

|

Alexandria |

|

Federal |

|

Strategic Library Automation (SLAM) |

|

|

|

Federal |

|

CDS ISIS |

|

|

|

Federal |

Koha |

|

|

|

|

Federal |

|

VIRTUAL |

|

|

|

Federal |

Koha |

|

|

|

|

Federal |

New

Gen Lib |

|

|

SLAM |

|

Federal |

|

Readable |

|

VIRTUAL, Alice for

Windows |

|

Federal |

Koha |

|

|

Alice for Windows |

|

Federal |

|

|

|

VIRTUAL |

|

Federal |

New

Gen Lib |

|

|

Millennium |

|

Federal |

Koha |

|

|

GLASS, LIB+ |

|

Federal |

Koha |

|

|

VIRTUAL |

|

State

|

|

SLAM |

|

|

|

State |

Koha |

|

|

|

|

State |

Koha |

|

|

X-Lib, SLAM |

|

State |

|

|

|

|

|

State |

Senayan LMS (SLMS) |

|

|

SLAM |

|

State |

|

|

|

|

|

State |

Koha |

|

|

|

|

State |

|

SLAM |

|

|

|

State |

|

Alice for Windows |

|

|

|

State |

Koha |

|

|

|

|

State |

Koha |

|

|

|

|

State |

|

|

|

|

|

State |

|

|

|

|

|

Private |

Greenstone |

|

|

|

|

Private |

Koha |

|

|

X-Lib |

|

Private |

New

Gen Lib |

|

|

|

|

Private |

Koha |

|

|

|

|

Private |

|

Millennium |

|

|

|

Private |

Koha |

|

|

|

|

Private

|

Koha |

|

|

|

Research

objective 1: Extent of ILS adoption in Nigeria university libraries.

Table 1a shows the state of ILS adoption in federal,

state, and private university libraries in Nigeria (see full list of university

libraries in this study in Appendix B).

Results in Table

1a show the ones adopted earlier as well as the ones in use in the

various university libraries represented in this study. It is evident in Table

1a that the majority of the Nigeria university libraries have adopted ILS for

the delivery of library services to their patrons. The results show that some

libraries had adopted a different ILS before adopting the current one in use

while for some libraries, the one currently in use is their first ILS. Results

in Table 1a also show a shift from the adoption of proprietary ILS among the federal

university libraries to open source ILS with 9 out of the 16 federal university

libraries in this study using Koha ILS. This may be connected to the problems

associated with the adoption and use of proprietary ILS. Results in Table 1a also show that only 10 federal university libraries, 2 state university

libraries and 1 private university library out of the 36 libraries represented

in this study had earlier adopted ILS while 23 of the libraries had none in

use. However, results in Table 1a show

some improvement on the extent of adoption of ILS as 31 of the libraries among

the 36 in this study have adopted ILS with only 5 of the libraries that have

none in use.

The results in Table

1b show the types of ILS that are adopted in university libraries in

Nigeria. It is evident in Table 1b that all the libraries that started the use

of ILS adopted only proprietary ILS since none of the libraries in this study

had open source ILS. This shows that in the past, Nigeria university libraries

selected proprietary ILS more frequently than open source ILS, allowing the

proprietary ILS to thrive despite research that reported its shortcomings.

Results also show that out of the 36 libraries in this study, 8 libraries (4

federal, 3 state, and 1 private) are currently using proprietary ILS. Furthermore, results in Table 1b show that out of the 13 state university libraries, 4 are yet to

adopt ILS for library services. It is interesting to note that federal

libraries have predominantly changed systems in this study, while open source

ILS was not initially adopted by any of the libraries. This means that the

federal university libraries are at the forefront of adopting ILS in Nigeria

than the state and private universities. The higher number of federal

university libraries that adopted ILS may be the result of the effort made by

the World Bank in collaboration with the National Universities Commission

(NUC), which supported 20 federal universities in Nigeria with TINLIB

automation software.

Research objective 2: Level of achievements with ILS in Nigeria

university libraries

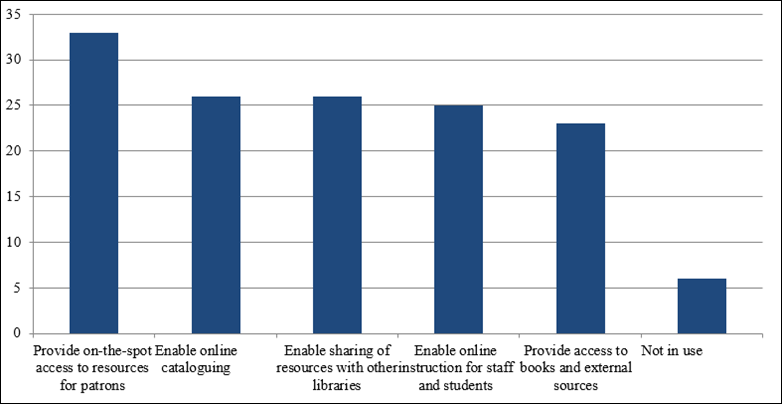

The results shown in Figure 2 demonstrate some strides that have been made by the

university libraries in Nigeria with the use of ILS. The results indicate that

out of the 36 respondents from the various libraries in this study, as shown in

Appendix A, a majority or 30 of them specify that the ILS adopted at their

various libraries provided on-the-spot access to resources for their patrons.

Results shown in Figure 2 also suggest that adoption of ILS in university

libraries in Nigeria enable sharing of information resources with other

libraries as attested by 26 of the respondents. Others key results include the

use of online cataloguing, accessing books and external sources, and making

online instruction available for staff and students. The result shows that

Nigeria university libraries are making progress in library services through

the use of ILS. Perhaps this is also due to the increasing number of ILS that is

now in use in the university libraries as shown in Table 1a.

Figure

2

Achievements

made with ILS in university libraries in Nigeria

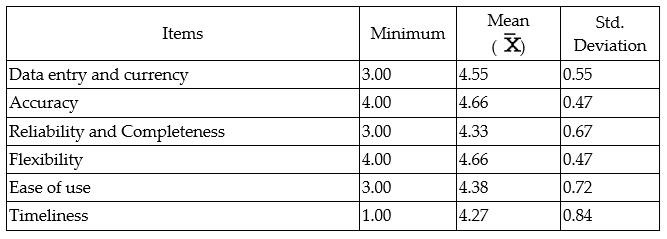

Table 2

Performance

of ILS in Library Services

Research

objective 3: Performance of ILS in library services in Nigeria

university libraries

In Table 2, the results show an impressive performance

of the ILS that are adopted in various university libraries throughout Nigeria.

Results reveal that ILS accuracy and flexibility are good ![]() = 4.66

respectively while data entry and currency has

= 4.66

respectively while data entry and currency has![]() = 4.55. On the

ease of use, reliability and completeness, ILS results show higher mean,

= 4.55. On the

ease of use, reliability and completeness, ILS results show higher mean, ![]() = 4.38 and 4.33

respectively. Result on the timeliness of ILS shows a mean of

= 4.38 and 4.33

respectively. Result on the timeliness of ILS shows a mean of ![]() = 4.27.

= 4.27.

The findings in Table 2 indicate that the adoption of

ILS would improve the overall performance and increase productivity of the

library because of timeliness, reliability, and accuracy in providing resources

for teaching, learning, and research, as well as gathering statistics of all

the activities within the ILS. In addition, the flexible nature of ILS makes it

easier for both librarians and users to use it in performing their duties and

assignments.

Research

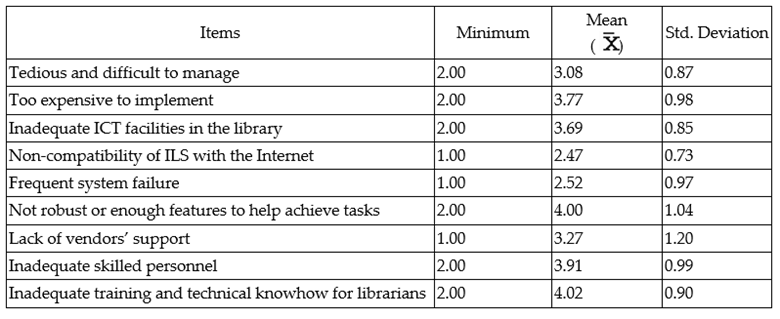

objective 4: Shortcomings of ILS in Nigeria university

libraries

The results in Table 3 reveal the shortcomings of ILS adoption in

university libraries in Nigeria. The table focuses on those factors

(shortcomings) that impede the performance and achievements of university

libraries in their use of ILS in Nigeria.

The

results in Table 3 show that among the factors that count as shortcomings in

the use of ILS in libraries, robustness, inadequate training, and technical

knowhow have a higher mean of 4.0 respectively. This means that these are the

major shortcomings of ILS in the libraries. Other shortcomings of ILS in

Nigeria university libraries in Table 3 are inadequate skilled personnel ![]() = 3.91, high cost of implementation

= 3.91, high cost of implementation ![]() = 3.77, inadequate ICT facilities in the

library X = 3.69, tedious and difficult to manage

= 3.77, inadequate ICT facilities in the

library X = 3.69, tedious and difficult to manage ![]() = 3.08, lack of vendors’ support

= 3.08, lack of vendors’ support ![]() = 3.27, and frequent system failure

= 3.27, and frequent system failure ![]() = 2.52. Results in Table 3 indicate that

non-compatibility with the Internet is less of a shortcoming for the adoption

of ILS in libraries than the other items listed in Table 3. This implies that

improving all of the shortcomings as shown in this result, would enhance the

achievements and performance of ILS in university libraries.

= 2.52. Results in Table 3 indicate that

non-compatibility with the Internet is less of a shortcoming for the adoption

of ILS in libraries than the other items listed in Table 3. This implies that

improving all of the shortcomings as shown in this result, would enhance the

achievements and performance of ILS in university libraries.

Discussion

The findings in this study

clearly demonstrate the importance of adopting Hamilton and Chervany’s

CVs for the evaluation of ILS in university libraries in Nigeria and across the

world. It further reveals the significance of using a holistic approach for the

evaluation of ILS, with the inclusion of shortcomings as proposed in the model

in Figure 1 before the adoption of ILS, to eliminate the risk of failure and

the tendency of switching from one system to another. It is evident from this

study that most of the university libraries in Nigeria had at one time or

another switched from one system to another which might have affected their

performance, achievement, and productivity. This scenario could be avoided when

a thorough evaluation of the performance, achievements, and shortcomings is

done on a new ILS prior to implementation.

Table 3

Shortcomings of ILS in Nigeria

University Libraries

Taking a critical look at

Hamilton and Chervany CVs and Farajpahlou’s

criteria, including the evaluation of shortcomings, before deciding on the

adoption of ILS, has the potential of helping the library to identify and avoid

problems when implementing a new or second ILS. Such conscious evaluation would

help to identify a feasible system. The findings in this study showed a gap in

the evaluation criteria that has been bridged by the model as shown in Figure

1. It would also be beneficial for university libraries in Nigeria and other

parts of the world that are yet to adopt any ILS, to focus its evaluation

criteria on the Hamilton and Chervany proposal, Farajpahlou evaluation criteria, this current study, and

possibly others. This approach could help to eliminate challenges that may

arise in the future.

The

findings in Table 3 show some of

the shortcomings of ILS in Nigeria university libraries. They indicates that among the factors, robustness, inadequate

training, and technical knowhow have a higher mean of 4.0 respectively. This

means that those variables are the major shortcomings of ILS adoption in

Nigeria university libraries. These shortcomings needs

to be critically examined because it has become a recurrent issue in some

recent studies, for instance, Osaniyi (2010), Omeluzor et al. (2012) and Ojedokun,

Olla and Adigun (2016) have reported on some of these shortcomings without

recommending the use of either CVs or Farajpahlou’s

evaluation criteria, which would have provided acceptable criteria to evaluate

ILS in libraries. The same shortcomings as shown in Table 3 have remained major hindrances for the adoption of ILS in

some university libraries in Nigeria and other parts of the world. These

shortcomings are directly or indirectly affecting the functions and performance

of the university libraries when it comes to the delivery of quality library

services to their patrons.

Limitations and

Opportunities for Further Study

This

study was limited to 36 university libraries from the 6 geo-political zones in

Nigeria. The method of the study was limited to a structured online

questionnaire without a face-to-face administration of the questionnaire and

interview guide. The data collected and analyzed in this study were from the

few selected university libraries in the six geo-political zones. A study of more

university libraries in Nigeria using qualitative methods might produce

different results and provide additional information. Future studies might

investigate factors that would influence the choice for the adoption of ILS in

libraries and how to overcome some of the shortcomings that are revealed in

this study.

Conclusion and

Recommendations

The main reason for the adoption and use of ILS in

libraries is to enable quality management and delivery of library services,

improving access and easy retrieval of information resources. In my opinion,

the library patrons of today have high expectations of library services and

are, for the most part, not satisfied with traditional methods. Within the last

decade, university libraries in Nigeria have witnessed a turnaround in the

adoption of ILS despite the disparaging remarks of Aguolu

and Aguolu (2006). The transformation being witnessed

in the Nigeria university libraries through the use of ILS is tremendous as

revealed by Oladokun and Kolawole (2018). Furthermore,

the performance of ILS in Nigeria university libraries as it relates to Farajpahlou’s (1999) criteria for assessing the success of

ILS is encouraging. These criteria include data and currency, accuracy,

reliability and completeness, flexibility, ease of use, and timeliness. That

said, several shortcomings still exist in the adoption and use of ILS in

Nigeria university libraries. Improving ILS adoption will require a conscious

effort and decisiveness to ensure that librarians and library patrons enjoy the

benefits that ILS offer. ILS developers should be able to consider the dynamic

needs of university libraries and their patrons and therefore incorporate those

specific features of Hamilton and Chervany’s CVs in

their ILS design, while keeping in mind the shortcomings presented in this

study. This type of thoughtful design will enhance the quality of library

services offered to patrons. Due to the various challenges facing university

libraries in Nigeria, and some other countries in the world, and the failure of

some libraries to adopt a robust ILS, the following recommendations are put

forward:

- Proper planning, adoption and implementation of

ILS in libraries should be the library’s first step.

- ILS developers should strive to gather feedback

from the ILS user community to identify some of the shortcomings, leading

to product enhancement.

- Future developments in ILS should incorporate

tested theories such as Hamilton and Chervany’s

CVs and Farajpahlou’s criteria in order to meet

certain expectations of librarians.

- University libraries should be at the forefront

of providing necessary changes in the delivery of information services

through the adoption and use of viable ILS.

- TETFund support for the funding of government owned universities in

Nigeria should be encouraged and sustained while alternative sources of

funding should be sought for ILS adoption in university libraries.

- University librarians in Nigeria should adopt a

system for the training and up skilling of staff to help in acquiring

relevant skills and knowledge related to the use of ILS for library

services.

References

Adegbore, A. M. (2010). Automation in two Nigerian university libraries. Library Philosophy and Practice (e-journal),

Paper 425. Retrieved from: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/libphilprac/425

Agboola, A.T. (2000). Five decades of Nigerian university

libraries: A review. Libri, 50 (41), 27-34. https://doi.org/10.1515/LIBR.2000.280

Aguolu, C. C. & Aguolu, I. E. (2006). The impact

of technology on library collections and services in Nigeria, In the Impact of

Technology on Asian, African and Middle Easter Library Collections, ed. R.

Sharma (Lanham, Md.: Scarecrow Press, 2006), 145.

Akpokodje, N. V. & Akpokodje, T. E. (2015). Assessment and evaluation of Koha

ILS for online library registration at University of Jos, Nigeria. Asian Journal of Computer and Information

Systems, 3 (1), 20-27.

Ani, O. E.

(2007). ICT revolution in African librarianship: Problems and prospects. Gateway Library Journal, 10 (2),

111-117.

Atua-Ntow, C. (2016). Staff assessment of the success of the integrated library

system: The case of the University of Ghana library system. http://hdl.handle.net/2263/59625 Retrieved from https://repository.up.ac.za/bitstream/handle/2263/59625/Ntow_Staff_2017.pdf?sequence=4&isAllowed=y

Ayiah, E. M. & Kumah, C. H. (2011, August 13 -

18). Social networking: a tool to use for effective service delivery to

clients by African Libraries [Paper presentation]. A paper presented at the

World Library and Information Congress: 77th IFLA General Conference

and Assembly. San Juan, Puerto Rico. https://cf5-www.ifla.org/past-wlic/2011/183-ayiah-en.pdf

Breeding, M. (2009). Opening up library automation software. Computers in

Libraries, 29(2), 25-28. Retrieved from https://librarytechnology.org/document/13803

Farajpahlou, A. H. (1999). Defining some criteria for the success of automated

library system. Library Review, 48(4), 169-180. https://doi.org/10.1108/00242539910276451

Farajpahlou, A. H. (2002). Criteria for the success of automated library systems:

Iranian experience (application and test of the related scale). Library Review, 51(7), 364-3721. https://doi.org/10.1108/00242530210438664

Hamilton, S. & Chervany,

N. L. (1981). Evaluating information system effectiveness – part 1: comparing

evaluation approaches. MIS Quarterly,

5(3), 55-69. https://doi.org/10.2307/249291

Hill, J.C. & Patterson, C. (2013). Assessment from

a distance: A case study implementing focus groups at an Online Library. College & Undergraduate Libraries, 20(3-4), 399-413. https://doi.org/10.1080/10691316.2013.829376

Kumar, V. & Jasimudeen,

S. (2012). Adoption and user perception of Koha Library Management System in

India. Annals of Library and Information

Studies, 59, 223-230. Retrieved from https://core.ac.uk/reader/11890295

Lucidea.com (n.d.). The

integrated library system (ILS) primer. Retrieved from https://lucidea.com/special-libraries/the-integrated-library-system-ils-primer/

Mbakwe, C. E. & Ibegbulam, I. J. (2014). Efforts

and challenges of automation of University of Nigeria, Enugu Campus Library [Paper

presentation]. A paper presented at the Nigeria Library Association, Enugu

State Chapter 14th annual conference and general meeting, Enugu

State., November 25 – 29.

Nok, G. (2006). The challenges of computerizing a university library in

Nigeria: The case of Kashim Ibrahim Library, Ahmed

Bello University, Zaria. Library

Philosophy and Practice, 8 (2), 1-9. https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/188041074.pdf

Nworgu, B.G. (2006). Educational Research: Basic Issues and Methodology. (2nded.). Nsukka: University Trust

publishers, p. 23.

Ojedokun, A. A., Olla, G.O.O., & Adigun, S.A. (2016). Integrated library

system implementation: The Bowen University Library experience with Koha

software. African Journal of Library

& Information Science, 26(1), 31- 42. http://www.ajol.info/index.php/ajlais/article/view/135088

Okiy, R. B. (1998). Nigerian university libraries and the challenges of

information provision in the 21st century. Library Bulletin, 3(1

& 2), 17-28.

Okpokwasili, N. P. & Blakes, E. (2014). Users’ participation in acquisition and

users’ satisfaction with the information resources in university libraries in

the South-South zone of Nigeria. Journal

of Research in Education and Society, 5(3), 71.-85. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/332321278_Authors'_Reputation_and_Users'_Satisfaction_with_the_Information_Resources_in_University_Libraries_in_the_South-South_Zone_of_Nigeria

Oladokun, T. & Kolawole, L.F. (2018). Sustainability of Library Automation

in Nigerian Libraries: Koha Open Source Software. Library Philosophy and

Practice. Paper 1929. Retrieved from https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/libphilprac/1929/

Omeluzor, S. U. & Oyovwe-Tinuoye, G. O. (2016).

Assessing the adoption and use of Integrated Library System (ILS) for library

service provision in academic libraries in Edo and Delta States, Nigeria. Library

Review, 65(8/9), 578-592. https://doi.org/10.1108/lr-01-2016-0005

Omeluzor, S.U., Adara, O., Madukoma,

E., Bamidele, I.A. & Umahi, F.O. (2012). Implementation

of Koha integrated library management software (ILMS): The Babcock University

experience. Canadian Social Science, 8(4),

211-221. https://doi.org/10.3968/j.css.1923669720120804.1860

Osaniyi, L. (2010). Evaluating the X-Lib Library Automation System at Babcock

University, Nigeria: A case study. Information Development, 26(1),

87-97. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1177/0266666909358306

Riaz, M. (1992). Library Automation. ITIC

Publishers and Distributors: New Delhi. 61.

Sani, A. & Tiamiyu, M.

(2005). Evaluation of automated services in Nigerian universities. The Electronic Library, 23 (3),

274-288. https://doi.org/doi 110.1108/02640470510603679

Sharma, R. N. (2009). Technology and academic

libraries in developing nations [Paper presentation]. A paper presented at International

Conference on Academic Libraries (ICAL), India. p.23.

Shekarau, M. I. (2014). List of certified librarians

in Nigeria, 2014. Librarians’ Registration Council of Nigeria (LRCN)

Directories, p. iii

Singh, K. (2013). Impact of technology in library

services. International Journal of Management and Social Sciences Research

(IJMSSR), 2(4), 74-76. Retrieved from http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.300.9109&rep=rep1&type=pdf

Uzomba, E. C., Oyebola, O. J. & Izuchukwu, A. C. (2015). The use and application of open

source integrated library system in academic libraries in Nigeria: Koha

example. Library Philosophy and Practice. Paper 1250. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/libphilprac/1250

Appendix A

Questionnaire on

the Evaluation of Integrated Library System in University Libraries in Nigeria:

An Empirical Study of the Achievements, Performance and Shortcomings

Dear Respondent,

This questionnaire may take about 10 minutes and is

designed to elicit data for the evaluation

of Integrated Library System (ILS) adoption in Nigeria University Libraries

focusing on the Achievements, Performance and Shortcomings. Information

provided on this questionnaire will be used strictly for the purpose of this

research. Please note that the respondent is not under any obligation to

respond to the questions. However, the researcher appeals for your assistance

in order to achieve the purpose of this study on schedule.

Thank you.

Researcher

Section 1: Demographic

Information of Respondents

a) What is the name of your University ………………………………………………………………

b) What is your gender Male Female

c) How long have you worked in your university

0-5 years 6-10

years 11-15 years 16-20 years

21-25 years 26-30 years 31

years and above

Section 2: Extent

of ILS adoption in Nigerian University Libraries

d) Which ILS is in use at your Library? Please specify: ……………………………………………..

e) Does your University use one previously?

Yes

No

Maybe

f) If your answer to question 5 is yes, which one was that

………………………………………….

Section 3: Achievements

made with the adoption of ILS in Library services

g) Kindly indicate some of the achievements that your university has made

with ILS

|

Statement |

tick |

|

Provide

on-the-spot access to resources to patrons |

|

|

sharing

of resources with other libraries |

|

|

Enable

online cataloguing |

|

|

Provide

access to books and external sources |

|

|

Online

instruction of staff and students |

|

|

Not

in-use at the moment |

|

Section 4: Performance

level of ILS in Nigeria University Libraries

h) How will you rate the performance of the ILS in your library?

|

Items |

Very good |

Good |

Poor |

Very poor |

Highly poor |

|

Data entry |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Accuracy |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Reliability and completeness |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Flexibility |

|

|

|

|

|

|

East of use |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Timeliness |

|

|

|

|

|

Section 5: Shortcomings

of ILS adoption in Nigeria University Libraries

i) What are the shortcomings of ILS adoption in university libraries in

Nigeria?

|

Items |

Strongly agree |

Agree |

Strongly disagree |

Disagree |

Not sure |

|

Tedious and difficult

to manage |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Too expensive to

implement |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Inadequate ICT

facilities in the library |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Non-compatibility of

ILS with the Internet |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Frequent system

failure |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Not robust or enough

features to help achieve tasks |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Lack of vendors’

support |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Inadequate skilled

personnel |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Inadequate training

and technical knowhow for librarians |

|

|

|

|

|

Appendix B

The selected federal, state and private universities in Nigeria used in

the study

|

SN |

University |

Ownership |

|

1. |

Ahmadu

Bello University, Zaria (ABU) |

Federal |

|

2. |

Bayero

University Kano (BUK) |

Federal |

|

3. |

Federal

University Lokoja (FUL) |

Federal |

|

4. |

Federal

University of Petroleum Resources Effurun (FUPRE) |

Federal |

|

5. |

Federal

University of Technology, Akure |

Federal |

|

6. |

Michael

Okpara Uni. of Agric., Umudike (MOU) |

Federal |

|

7. |

Nnamdi

Azikiwe University, Awka |

Federal |

|

8. |

Obafemi

Awolowo University, Ile-Ife (OAU) |

Federal |

|

9. |

University

of Agriculture, Markudi |

Federal |

|

10 |

University

of Benin (UNIBEN) |

Federal |

|

11 |

University

of Ibadan (UI) |

Federal |

|

12. |

University

of Ilorin (UNILORIN) |

Federal |

|

13. |

University

of Jos (UNIJOS) |

Federal |

|

14. |

University

of Lagos (UNILAG) |

Federal |

|

15. |

University

of Nigeria, Nsukka (UNN) |

Federal |

|

16. |

University

of Port Harcourt (UNIPORT) |

Federal |

|

17. |

Ambrose

Ali University, Kano (AAU) |

State |

|

18. |

Bauchi

State University |

State |

|

19. |

Benue

State University (BSU) |

State |

|

20. |

Delta

State University, Abraka (DELSU) |

State |

|

21. |

Ebonyi

State University, Abakiliki (ESUA) |

State |

|

22. |

Ekiti

State University (ESU) |

State |

|

23. |

Ignatius

Ajuru University of Education(IAUOE),Rumuolumeni, Port Harcourt |

State |

|

24. |

Imo

State University, Owerri |

State |

|

25. |

Kogi

State University, Anyigba |

State |

|

26. |

Lagos

State University, Ojo (LASU) |

State |

|

27. |

Olabisi

Onabanjo University, Ago Iwoye (OOU) |

State |

|

28. |

Tai Solarin University of Education, Ijebu-Ode (TASUED) |

State |

|

29. |

University

of Medicine, Ondo (UMO) |

State |

|

30. |

American

University of Nigeria, Yola (AUN) |

Private |

|

31. |

Babcock

University, Ilishan-Remo (BU) |

Private |

|

32. |

Bingham

University |

Private |

|

33. |

Bowen

University, Iwo (BUI) |

Private |

|

34. |

Landmark

University, Omu-Aran. |

Private |

|

35, |

Rhema

University, Obeama-Asa, Abia

State |

Private |

|

36. |

Samuel

Adegboyega University, Ogwa

(SAU), Ogwa, Edo |

Private

|