Research Article

University Students’ Changing Library Needs and Use: A

Comparison of 2016 and 2018 Student Surveys

Jung Mi Scoulas

Clinical Assistant Professor

and Assessment Coordinator

University of Illinois at

Chicago, University Library

Chicago, Illinois, United

States of America

Email: jscoul2@uic.edu

Sandra L. De Groote

Professor and Head of

Assessment and Scholarly Communications

University of Illinois at

Chicago, University Library

Chicago, Illinois, United

States of America

Email: sgroote@uic.edu

Received: 10 Aug. 2019 Accepted: 6 Jan. 2020

![]() 2020 Scoulas and De Groote. This is an Open

Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

2020 Scoulas and De Groote. This is an Open

Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

DOI: 10.18438/eblip29621

Abstract

Objective

– This study examines differences in university

students’ library use and satisfaction (e.g., in-person library visits, online

and print resource use, space satisfaction, and library website use) between

2016 and 2018 based on local survey data. It also discusses how these findings

provided guidance for future planning and action.

Methods – The academic university library developed the

surveys for undergraduate and graduate students and distributed them in Spring

2016 and 2018.

Both student surveys focused on examining students’ needs relative to library

resources and services, although the 2018 student survey also attempted to

quantify students’ library visits and their use of library resources. While

the surveys were not identical, the four questions that appeared in both

surveys (i.e., library visits, resource use, library space satisfaction, and

library website use) were recoded, rescaled, and analyzed to measure the

differences in both surveys.

Results – The

survey results reveal that students’ library visits and use of library

resources in 2018 were higher than in 2016. In particular, undergraduate students’ use of library

resources in 2016 were lower than those in 2018, whereas graduate students’ use

of library resources remained similar in both years. Another key finding

indicates that the mean score of students’ library quiet study space

satisfaction in 2018 was higher than in 2016. However, when compared to

the 2016 survey, there was a decrease in students’ ease of library

website use in the 2018 survey.

Conclusion

– Assessing students’ behavior and satisfaction

associated with their use of library physical spaces, resources, and services

should be conducted on an ongoing basis. Over time, the survey findings can be

used as evidence based data to communicate patterns of users’ behavior and

satisfaction with various stakeholders, identify areas for improvement or

engagement, and demonstrate the library’s impact. Survey results can also

inform further strategic and assessment planning.

Introduction

Academic libraries have utilized various assessment measures to

understand users’ needs, improve their services, and further demonstrate the

value of the library. Surveys are a popular assessment tool widely used for

exploring users’ needs in academic libraries (Liebst

& Feinmark, 2016; Matthews, 2007). While various

user surveys are conducted by academic libraries, two major types of user

surveys are standardized surveys (e.g., LibQUAL+, Measuring Information Service Outcomes) and local surveys developed by

individual academic libraries (e.g., Montgomery, 2014; Scoulas & De Groote,

2019). Regardless of the type of user surveys, many academic libraries attempt

to use an evidence based approach by reviewing the survey findings, using those

findings for making decisions, and monitoring changes over time (Dennis,

Greenwood & Watson, 2013; Greenwood, Watson & Dennis, 2011; McCaffrey

& Breen, 2016; McCaffrey, 2019; Montgomery, 2014; Norton, Tennant, Edwards

& Pomputius, 2018; Taylor & Heath, 2012).

The University of Illinois at Chicago (UIC) Library began using surveys

as a way to understand users’ perceptions and needs related to the university

library’s spaces, services and resources. The findings have allowed for an

evidence based approach to identify areas for change or improvement. The

principle involved in this effort is to establish the culture of assessment

within the library, “an organizational

environment in which decisions are based on facts, research, and analysis, and

where services are planned and delivered in ways that maximize positive

outcomes and impacts for customers and stakeholders” (Lakos

& Phipps, 2004, p. 352). This has been done using a standardized survey

like LibQUAL+ (2002, 2006, and 2012), as well as

local surveys focused on specific aspects (e.g., library website, space,

services) as needed. The university library decided to discontinue use of LibQUAL+ because it was not always possible to apply the

findings to decision making and because of complaints that the survey was too

complicated to take. Locally focused surveys had been conducted at various

times at the UIC Library to help guide changes related to space (e.g., adding

furniture, remodeling spaces, installing a coffee shop). However, a major

challenge was a lack of an instrument to benchmark and monitor users’

perceptions of library resources, services, and space over time and to measure

the impact of students’ library use on their academic success. Beginning in

2015, the Assessment Coordinator Advisory Committee (AC2) at the UIC Library

developed user experience surveys for students (2016 and 2018) and faculty

(2017 and 2019).

The purpose of this study is to examine any reported measurable

differences in university students’ experiences using the library between 2016

and 2018. The study also explores which survey findings provide actionable data

for the library to use, and it also describes the actions the university

library took as a result of the survey data. This paper will be a useful guide

for librarians who:

- are considering developing their own instrument

to capture users’ needs and to track those changes over time;

- already have a locally developed instrument but

are considering revising it to collect more meaningful data;

- are not sure how to take action based on their

own findings from previous user surveys;

- want to strengthen the culture of assessment

within their library.

Literature Review

Academic libraries have exerted great effort to establish a culture of

assessment using evidence based approaches to explore what library users want

and how to provide easy access to library services and resources. A survey of academic

libraries in the United States (U.S.) showed that more than 70% of academic

libraries used “assessment data to improve practice” (Farkas, Hinchliffe & Houk, 2015, p. 157). Most important, the goal is to improve

the quality of the library’s resources and services for users based on the

results of the assessment efforts. Improving user services and demonstrating

the value of the library to its stakeholders are among the primary missions of

academic libraries. In a fast-paced academic environment, academic libraries

cannot play a large role in students’ efforts to accomplish their academic

goals without understanding students’ needs and preferences.

User Surveys at Academic Libraries and Use of Findings

Many academic libraries have implemented user surveys

to understand users’ behaviors, attitudes toward and satisfaction with library

services and resources so as to improve current practices based on the results.

One of the popular and widely used standardized user surveys used by academic

libraries is LibQUAL+. LibQUAL+

is a web-based survey tool administered by the Association of Research

Libraries (ARL). Since 2000, more than 1,300 academic and public libraries have

used this survey tool (ARL, n.d.). LibQUAL+ is

regarded as a useful tool for librarians and administrators to effectively

gather users’ feedback, a stable instrument to continuously track users’

behavior over time, and a benchmark to help libraries gauge their success

against other institutions (ARL, n.d., Hinchliffe, 2015; McCaffrey, 2019;

Taylor & Heath, 2012). Several academic libraries using LibQUAL+

explored how users’ perceptions of library services and resources changed over

time and how the academic libraries implemented changes in response to the

survey results (Dennis et al., 2013; Greenwood et al., 2011; McCaffrey, 2019;

McCaffrey & Breen, 2016; Taylor & Heath, 2012). In spite of the

popularity of the LibQUAL+ survey, there are reports

of limitations with the tool. Challenges of using LibQUAL+

include participants having difficulty in completing the survey due to too many

questions and similarity among questions (Voorbij,

2012); difficulty in understanding the fixed survey questions, such as minimum,

perceived, and desired levels of service quality (Thompson, Cook, & Health,

2000); difficulties in connecting the LibQUAL+ data

with locally collected statistics (e.g., gate counts); a lack of flexibility to

customize questions; and difficulty reading

results (Dennis et al., 2013). Dennis and colleagues (2013) suggested

that alternative survey methods besides LibQUAL+ are

needed to measure changes within the library.

Several academic libraries have developed their own local user surveys

to gauge users’ behaviors and needs and used the findings for improvement

(e.g., Montgomery, 2014; Ojennus & Watts, 2017).

Benefits of using a local survey are that academic libraries can customize

their questions and response options and focus on a specific area that they

intend to investigate (e.g., space). For example, Ojennus

and Watts (2017) conducted an online survey in 2015 of all students at

Whitworth University in order to examine how they used the library (e.g., space

and technology) and identify possible areas for improvement. After comparing

their findings with trends identified in the literature, the authors concluded

that their findings revealed local needs and interests. As a result, the

library director at Whitworth University made several changes to library space

and amenities (e.g., offering free coffee and making more private rooms

available during finals week) and addressing problems with wireless access in

collaboration with the IT department (Ojennus &

Watts, 2017). Ojennus and Watts (2017) further stated

that they plan to continue surveying users to collect longitudinal data to

monitor the trends and evaluate “the efficacy of our responses to them” (p.

333).

While many surveys may be one-time investigations into users’ needs,

other researchers have studied user needs over extended periods of time using

local surveys. For instance, Montgomery (2014) at the Olin Library at Rollins

College conducted surveys two years in a row using the same survey

questionnaire to determine how users’ perceptions of their learning behavior

changed before and after library space renovations. The author commented that

they were satisfied with users’ feedback and were able to better understand

users’ learning behaviors at the library. The University of Florida Health

Science Center Library used a survey developed by the University of Southern California Health Sciences Libraries staff and

examined how health science users’ awareness of technology (e.g., mobile apps)

and their interest in using technology to access library resources and services

(e.g., citation tools and library

electronic resources) from their mobile devices changed from 2012 to 2016

(Norton et al., 2018). The authors stated that “the annual review of survey results has allowed librarians to identify

the local users’ needs and interests as they changed over time and has led to

incremental changes in services offered” (p. 329).

In spite of the advantages of conducting local surveys, some drawbacks

were raised in the literature: a lack of national benchmarking data and

challenges related to reliable and valid survey questions (Hinchliffe, 2015).

In addition, few studies addressed repeating user surveys over time to

monitoring users’ needs in various areas, such as space, usage of resources, or

technology.

Patterns of Students’ Library Experience

With the Internet and advanced technology, college students can easily

access books and journals remotely using their own computer or mobile device

without entering the library. The ability to remotely access e-books, journals,

databases, and services has shaped users’ library use patterns over 15 years.

Previous studies showed that easy access to online resources and students’

expectations of the library influenced students’ library use pattern (De

Groote, Hitchcock, & McGowan, 2007; Lee, Ritterbush,

& Sivigny, 2010). In two separate studies

conducted during periods of 14 years and 15 years, students’ in-person library

visits declined, whereas their reference questions via email and phone

increased (De Groote et al., 2007; Lee et al., 2010). According to statistics

from ARL, the patterns of students’ library visits also confirm that among 123

member libraries the number of users accessing the library (gate counts)

declined at 42% of academic institutions in the U.S. from 2015 to 2018. In

addition, in a recent article, Cohen (2019) stated that the trend in students

checking out print books decreased over the past decade, whereas the

availability of online articles and e-journal downloads increased.

Academic libraries efforts to meet users’ needs related to library space

(e.g., floor renovation, extending hours, reorganizing spaces) have shifted

from being collection oriented to user focused by incorporating users’

feedback. As a result, students’ perceptions of library space have evolved over

time; library space is becoming less traditional and more conducive to social

learning. Data from 2007 to 2014 from the University of Limerick in Ireland and

an international consortium of ARL and the Society of College, National and

University Libraries indicated that quiet space is increasingly considered

important for library users (McCaffrey & Breen, 2016). This pattern is also

confirmed by a recent study done by McCaffrey (2019) showing that users’

perceptions of quiet space have improved from 2007 to 2016. Other academic

libraries have also observed trends related to students using library space,

indicating that students used library space not only for working alone but,

depending on their learning needs, also for working with their peers

(Montgomery, 2014; Scoulas & De Groote, 2019). In one library, after

rearranging furniture in the library spaces, the overall library space usage

from 2015 to 2018 increased 15% and use of group study tables and a new group

study area increased about 270% (Oberlander, Miller, Mott & Anderson, 2019).

Assessing students’ needs on the library website is critical for

academic libraries: “Library websites are a gateway to library resources,

services, contact information, and events” (Anderson, 2016, p. 19). While

previous studies show that usage of library websites has declined over time

(Allen, Baker, Wilson, Creamer & Consiglio, 2013;

Anderson, 2016), libraries continue to improve their websites for students’

use. Mierzecka and Suminas

(2017) examined which features of the library website are most important for

students at the University of Warsaw in Poland and the Vilnius University in

Lithuania via open-ended responses. They found that the top five important

features of the library website were (ranked in order): the online library

catalogue, information about the location and opening hours, login account

access, the online collection, and a floor map showing reading rooms. Students’

library website experiences were also examined after changes were made to the

libraries’ websites.

Aims

The aim of this study is to examine the patterns of students’ library

use and satisfaction (in-person library visits, resource use, space

satisfaction, and library website use) based on responses to surveys

distributed to students in 2016 and 2018. This study also describes how these

results were used at evidenced based data to provide guidance for a plan of

action.

Methods

Institutional

Setting

UIC is a large public research university classified by the Carnegie

classification as having highest research activity. More than 30,000 students

are enrolled in all of its 15 colleges, and students have access to two large

libraries in Chicago (an arts, humanities, sciences, social sciences, and

engineering library and a health sciences library) and three smaller health

sciences libraries located at UIC’s regional areas (Peoria, Rockford, and

Urbana).

Survey

Development

The AC2, which consisted of library faculty representing various units

(research and instruction, collections, website, administration, assessment and

scholarly communications) in the university library, developed the surveys for

undergraduate and graduate students. The first locally developed survey,

consisting of 19 questions, was distributed to the institution’s students in

2016 (see Appendix A). Prior to distribution, the surveys were piloted with 6

to 8 students who read the questions and shared their thoughts aloud to allow

the research team to observe if there were any issues with interpreting the

questions. At the time of the data analysis, it was determined that effectively

analyzing all of the data was not possible and that changes to the survey would

be needed. For the 2018 student survey, the AC2 reviewed the 2016 student

survey questions and findings and revised some scales (e.g., converting

dichotomous to interval scales for frequency of in-person or online library

visits and library resource use), wording, and format of the survey (see

Appendix B). For further details of how the 2018 student experience survey was

revised, refer to Aksu Dunya and De Groote’s article

(2019). As a result of these changes, the surveys were not identical and

comparisons with all data points were not possible. However, several questions

did remain in both surveys and comparisons of the results to these questions

were conducted and reported in this paper.

Measures

Student Library Visits in Person and Use of

Library Resources

The response scales in the 2016 survey regarding

students’ in-person library visits and use of library resources were different

from those used in the 2018 survey. For example, in the 2016 survey In the

past year, have you visited the library at your campus site for study or

research? and In the past year, have you used [library resources]?

had a nominal scale of yes (1) and no (0), whereas in the 2018

survey Last semester, how often did you visit the university library?

and Last semester, how often did you use [library resources]? had an

ordinal scale of Never (0) to Daily (4). These items were

recorded, as follows: any responses from (1) to (4) in the 2018 survey data

were coded as yes (1) and the rest as no (0) to match those used

in the 2016 data.

Student Library Space

Satisfaction

The scales for the questions related to student

library space satisfaction (i.e., quiet study space and collaborative/group

space) in the 2016 survey were coded Very satisfied (1), Satisfied

(2), Neutral (3), Dissatisfied (4), Very dissatisfied (5),

and I do not use [this space] (6). On the other hand, the same questions

in the 2018 survey were coded from I don’t use this space in the library

(0), Very dissatisfied (1), Dissatisfied (2), Satisfied

(3), and Very satisfied (4). Given that the scales in the 2016 survey

were reverse coded in comparison to the 2018 survey scale, the 2016 data was

recoded so that, for example, Very satisfied (1) becomes Very

satisfied (5) and I do not use [this space] (6) to I do not use

[this space] (0) to match with the 2018 data. Prior to rescaling, the

frequency of I do not use this space (0) response in the 2016 and 2018

surveys was analyzed. Afterwards, the I do not use this space (0)

response was dropped from both the 2016 and 2018 survey results because this

response affects the calculation of the mean scores. Because the 2016 survey

used the 6-point Likert scale format including Neutral (3) and the 2018

survey was a 5-point Likert scale format, it was not possible to directly compare

the mean scores. Therefore, the data was rescaled by using the formula

developed by Preston and Colman (2000): (rating – 1) / (number of categories –

1) x 100. This method is used as a way to compare survey results when the

surveys used different scales.

To rescale the results of the survey, the 5-point

Likert scale data (1, 2, 3, 4, 5) in the 2016 survey was converted to a

continuous one (0, 25, 50, 75, 100), and the 4-point Likert scale data (1, 2,

3, 4) in the 2018 survey was converted to a continuous one (0, 33.33, 66.67,

100). Another adjustment was made for the library space satisfaction questions.

The space satisfaction questions in the 2016 survey included quiet study space

and collaborative/group space, but the 2018 survey questions included quiet

study space, collaborative space, and group study room, separately. To compare

the library space satisfaction in both surveys, the responses of collaborative

and group space in the 2018 survey were calculated as a mean score.

Student Use of Library Website

The scales for the question related to how easy it was to use features

of the library website (e.g., finding a book, searching for journal articles)

were originally coded as a 6-point Likert scale, from Very difficult (1)

to I have not used this (6) in the 2016 survey. However, these scales

were coded as a 5-point Likert scale in the 2018 survey from I don’t use

this service (0) to Very easy (4). For the procedure of recoding and

rescaling data for students’ library website usage, the authors followed the

same methods as described for library space satisfaction.

Preferred Location for Studying

Students were also asked why they studied in

places other than the library by selecting all of the responses that apply.

While the options were not the same for both years, several options were

relatively similar: more study space, quieter study space, food/drink

availability, and equipment or software that I need are available.

How to Spend Funding

Students were also asked how they would spend

funding to improve the library. They could select two options in the 2016

survey and three options in the 2018 survey. Not all of the options were the

same in both surveys, but the options from both surveys included more

computers, more quiet study spaces, and more electric outlets. However, more

food and drink options was included only in the 2018 survey.

Participants

The total number of respondents in 2016 was 1,087 (response rate of 4%),

whereas the number of respondents in 2018 was 2,277 (response rate of 8%). This

reflects a 109% increase over the response rate of the 2016 survey. Both

surveys contained key demographics, including gender, age, class level (e.g.,

undergraduate and graduate), first generation status, and commuter status. As

shown in Table 1, it appears that the ratio of respondents from the 2016 and

2018 surveys was similar to the ratio of the 2018 university population (a

difference of less than 5%) in all of the demographic variables, except for two

categories: female respondents and graduate students were overrepresented in

both surveys. As such, on the whole, the survey respondents were representative

of the university’s population.

There are slight differences between the 2016 survey and 2018 survey

respondents’ demographics. The percentage of student respondents in the age

group between 16 and 25 increased almost 10% from 2016 (59.52%) to 2018

(69.43%), whereas the rest of the age groups slightly decreased. The percentage

of undergraduate respondents increased about 9% from 2016 (48.30%) to 2018

(56.96%), and the first generation respondents increased more than 2% from 2016

(10.86%) to 2018 (13.22%). Some of the respondents’ demographics were similar

in both surveys. For example, in both surveys, female students (61.64% in 2016

and 63.68% in 2018) were more likely to participate in the survey than male

students (38.36% in 2016 and 36.14% in 2018). In additional, the majority of

the respondents in both surveys (85.19% in 2016 and 85.68% in 2018) were

commuters, meaning they did not live on campus.

Data Collection

Students’ demographic information was obtained from the Office of

Institutional Research (OIR) with the participating students’ consent for both

the 2016 and 2018 surveys. The demographic information requested for both

surveys included gender, age, class level, first generation status, and

commuter/resident/online status (see Table 1). The OIR uploaded a “panel” in

Qualtrics that contained all students’ email addresses and demographic

information. Students were sent an email from Qualtrics requesting their

participation in the survey. The procedures for collecting survey responses

remained the same for both surveys and are outlined in detail in the study of

Scoulas and De Groote (2019). As an incentive, all survey respondents were able

to enter a drawing for one of three iPads in the 2018 survey. No incentives

were offered with the 2016 survey.

Table 1

Comparison of Students’ Demographic Information: 2016 and 2018

|

|

Sample |

Total 2018 Student

Population (N = 28,725) |

|

|

|

2016 (n = 1,087) |

2018 (n = 2,277) |

|

|

Gender, n (%) |

|

|

|

|

Female |

670 (61.64%) |

1,450 (63.68%) |

15,201 (52.92%) |

|

Male |

417 (38.36%) |

823 (36.14%) |

13,408 (46.68%) |

|

Unknown |

- |

4 (0.18%) |

116 (0.40%) |

|

Age Group, n (%) |

|

|

|

|

16-25 |

647 (59.52%) |

1,581 (69.43%) |

20,598 (71.71%) |

|

26-35 |

297 (27.32%) |

509 (22.35%) |

6,206 (21.60%) |

|

Above 35 |

143 (13.16%) |

187 (8.21%) |

1,921 (6.69%) |

|

Class, n (%) |

|

|

|

|

Undergraduate |

525 (48.30%) |

1,297 (56.96%) |

18,886 (65.75%) |

|

Graduate |

536 (49.31%) |

980 (43.04%) |

9,839 (34.25%) |

|

First Generation, n (%) |

118 (10.86%) |

301 (13.22%) |

4,801 (16.71%) |

|

Transfer, n (%) |

211 (19.41%) |

463 (20.33%) |

6,890 (23.99%) |

|

Residency, n (%) |

|

|

|

|

Commuters |

926 (85.19%) |

1,951 (85.68%) |

24,584 (85.58%) |

|

Resident |

109 (10.03%) |

276 (12.12%) |

3,114 (10.84%) |

|

Online |

52 (4.78%) |

50 (2.20%) |

1,027 (3.58%) |

Data Analysis

All data was analyzed using SPSS 25. Descriptive

statistics were used in response to Q1, student library visits and resource

use. To test whether a statistically significant difference in student library

space satisfaction and use of the library website existed in the 2016 and 2018

survey data, an independent sample t-test was used. Before conducting any

statistical tests, the requirements of the assumptions of each test were

checked. The 2016 response and 2018 response distributions were sufficiently

normal for the purposes of conducting a t-test (e.g., skew < |2.0| and

kurtosis < |9.0|; Schmider, Ziegler, Danay, Beyer & Bühner, 2010).

In addition, the assumption that homogeneity of variances in spread scores is

equal in different groups of cases was tested and was not met via Levene’s F test.

Therefore, adjusted degrees of freedom were used.

Results

Comparison of

Student In-Person Library Visits and Resource Use

Table 2 shows the student library visit and library resource use in the

2016 and 2018 survey data. With respect to their frequency of library visits,

the results indicate that student library visits slightly increased from 2016

to 2018. In additional, the frequency of student library resource use (journal

articles, books, and databases) moderately increased from 2016 to 2018.

Students’ in-person library visits and library

resource use were further organized by class level (undergraduate students and

graduate students) in order to show whether or not there were differences in

their library use between surveys. Figure 1 shows that overall undergraduate

students visited the library more than graduate students in both years.

Undergraduate students’ in-person library visits in 2018 (51.30%) were higher

than in 2016 (46.00%), whereas graduate students’ in-person library visits in

2018 (35.31%) were slightly lower than in 2016 (38.91%).

Table 2

Comparison of Student In-Person Library Visits and Use in Both Surveys

|

|

2016 (n = 1,087) |

2018 (n = 2,277) |

||

|

|

n |

% |

n |

% |

|

In-person visits |

923 |

84.91 |

1,972 |

86.61 |

|

Use of library resources |

850 |

78.20 |

1,946 |

85.46 |

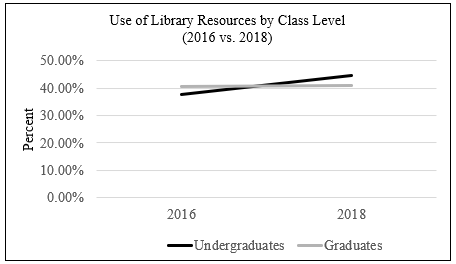

Regarding students’ use of library resources,

as shown in Figure 2, the patterns by class level across the two surveys were

different. For example, undergraduate students’ use of library resources in

2016 (37.63%) was lower than that in 2018 (44.62%), whereas graduate students’

use of library resources remained similar in both years (40.57% in 2016 and

40.84% in 2018). Undergraduate students’ use of library resources (37.63%) was

lower than graduate students’ (40.57%) in 2016, but in 2018 undergraduate students’

use of library resources (44.62%) was higher than graduate students’ use

(40.84%).

Library Space

Usage and Satisfaction

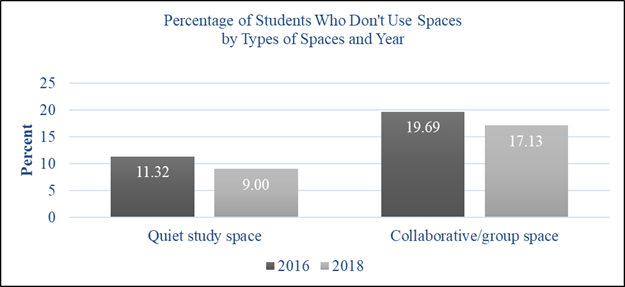

Prior to analyzing the comparison of students’ library space

satisfaction, the percentages of the respondents answering that they did not

use a space were analyzed (see Figure 3). This information allowed us to see

whether or not the patterns of students’ library space usage have changed over

time. As shown in Figure 3, the respondents who indicated not using the space

for both quiet study space and collaborative/group space (11.32% and 19.69%) in

2016 were higher than those in 2018 (9.00% and 17.13%). The findings suggest

that the respondents in 2018 were more likely to use the quiet study space and

collaborative/group space than respondents in 2016.

Figure 1

Students’ in-person library

visits by class level.

Figure 2

Students’ use of library resources by class

level.

Figure 3

Percentage of

students responding that they do not use quiet study space or

collaborative/group space in 2016 and 2018.

An independent sample t-test was conducted to compare further students’

library space satisfaction in 2016 and in 2018. As shown in Table 3, the

results show that there was a statistically significant difference in the

scores of quiet study space for the 2016 surveys (M = 67.47, SD = 26.65)

and 2018 surveys (M = 73.84, SD = 24.15); t(1356) = -5.72, p <

.001, d = 0.25. This result suggests that the average student

satisfaction in the quiet study space in the 2018 survey was higher than in the

2016 survey. However, there was no significant difference in the mean scores of

collaborative/group study space for 2016 (M

= 65.93, SD = 25.46) and 2018 (M = 68.25, SD = 23.47); t(1322)

= -1.97, p = .05, d = 0.09.

Library Website

Use and Ease of Use

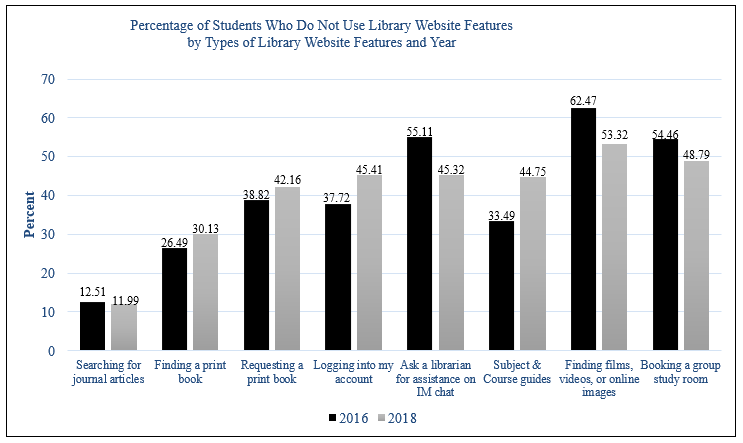

To see the pattern of students’ library website use in 2016 and 2018,

the responses indicating that students did not use a service were compared. The

findings show that the percentages of respondents who did not use services such

as asking a librarian for assistance on IM/Chat; finding films, videos, or

online images; and booking a group study room in 2016 were higher than those in

2018, meaning that students in 2018 tended to use those services more than

students in 2016 (see Figure 4). On the other hand, the percentages of

respondents who did not use services such as finding a print book, requesting a

print book, logging into my account, and subject and course guides in 2016 were

lower than those in 2018, suggesting that students in 2016 were more likely to

use those services than students in 2018.

Next, an independent sample t-test was conducted to investigate whether

there were differences in students’ ease of using the library website between

the 2016 and 2018 surveys. As shown previously in Table 3, the results of the

t-test indicate that there were statistically significant survey differences in

the ease of library website use, except for the finding media and booking a

group study room features, when comparing the 2016 survey with the 2018 survey

at the level of p < .05.

In 2016, the top reasons for studying in

places other than the library included more study space (42.41%), quieter study

space (37.72%), and food/drink availability (32.84%). However, in the 2018

survey, quieter study space was not in the top three responses. Instead, I

can find a seat was the top selection (46.90%), an option that was not

available in the 2016 survey. Studying in other places because of the

availability of food and drink increased (44.80%) and studying in other places

with more study space decreased (33.90%). In 2016, students indicated they

would spend funding on more online resources (24.38%), more computers (21.25%),

and more quiet study spaces (21.16%). In 2018, students indicated they would

spend funding on more food and drink options (32.37%), an option which was not

available in the 2016 survey. They also indicated the desire for more quiet

study space (31.14%) and more electric outlets (30.52%); compared to the

previous survey, both of these preferences increased compared to the previous

survey.

Table 3

Comparison

of Average Student Library Space Satisfaction and Library Website Ease of Use

in Both Surveys

|

|

2016 (2018)a |

||||||||

|

|

n |

M |

SD |

t |

df |

p |

95% Confidence Interval (Lower vs. Higher) |

Cohen’s db |

|

|

Student

Library Space Satisfaction |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Quiet study

space |

777 (1,799) |

67.47 (73.84) |

26.65 (24.25) |

-5.72 |

1356 |

*** |

-8.55 |

-4.18 |

0.25 |

|

Collaborative/group

space |

686 (1,231) |

65.93 (68.25) |

25.46

(23.47) |

-1.97 |

1322 |

|

-4.64 |

-.01 |

0.09 |

|

Ease

of Use of Library Website Features |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Searching for

journal articles |

748 (1,813) |

79.08 (72.79) |

23.32 (22.53) |

6.27 |

1350 |

*** |

4.32 |

8.26 |

0.27 |

|

Finding a

print book |

601 (1,391) |

74.63 (68.18) |

25.47 (25.42) |

5.19 |

1136 |

*** |

4.01 |

8.89 |

0.13 |

|

Requesting a

print book |

460 (1,114) |

78.37 (66.76) |

26.08 (26.26) |

8.02 |

862 |

*** |

8.77 |

14.46 |

0.44 |

|

Logging into

my library account |

477 (1,027) |

81.13 (70.66) |

24.04 (25.83) |

7.68 |

991 |

*** |

7.80 |

13.15 |

0.18 |

|

Asking a librarian for assistance on IM/Chat |

281 (1,038) |

80.61 (76.56) |

22.99 (23.84) |

2.60 |

456 |

* |

.98 |

7.11 |

0.17 |

|

Using library

subject and course guides |

515 (1,051) |

75.78 (69.84) |

24.94 (23.24) |

4.53 |

960 |

*** |

3.36 |

8.51 |

0.24 |

|

Finding films, videos, or

online images |

202 (845) |

66.46 (67.26) |

28.40 (25.62) |

-.37 |

284 |

|

-5.10 |

3.50 |

0.03 |

|

Booking a

group study room |

282 (950) |

71.37 (69.61) |

26.97 (26.34) |

.96 |

452 |

|

-1.82 |

5.33 |

0.07 |

aResults from the 2018 survey are provided in parentheses.

bCohen’s d: 0.2= small effect, 0.5= moderate effect, 0.8= large effect.

* p < .05.

*** p < .001.

Figure 4

Percentage of students responding that they do

not use a website feature in 2016 and 2018.

Discussion

Patterns of Students’ Library Use

Using the 2016 and 2018 survey results, the current study examined if

there were differences in students’ library use in four areas: library visits,

resources, library space, and the website. The findings of this study

illustrate that, even within a short period of time between surveys (in this

case, 2 years), there were differences in users’ library use. From 2016 to

2018, there was an increase in students’ library visits, resource use, and

satisfaction, and there was a decrease in the ease of library website use.

Finding an increase in library visits is different from the decrease in

students’ library visits indicated in the literature (ARL [statistics from 2016

to 2018]; De Groote et al., 2007; Lee et al., 2010). However, students’

resource use was similar to what has been shown in the literature with an

increase in students’ online resource use such as e-journals (ARL [statistics

from 2016 to 2018]; Cohen, 2019). Continued efforts to provide space for

students may have contributed to the increase in undergraduate use of the

library. The findings about the increased use of library resources may be associated

with libraries providing a higher number of resources. In fact, according to

ARL Statistics, from 2016 to 2018 the volumes and e-books in the university’s

library collection have increased 37.16% and 60.44%, respectively. Use of the

library decreased between the survey period for graduate students. It could be

that the heavy presence of undergraduate students was a deterrent to graduate

student use.

From Analyzing Findings to Taking Action

The second goal of this paper is to discuss how the findings from the

survey were used to take further action. The findings from the surveys and

comparative data were presented to the AC2, to the steering committee, and to

all library staff to share the overall patterns of students’ library

experiences in various areas and demonstrate how the library is doing. The

findings were also shared with external stakeholders like the Faculty Advisory

Committee at the UIC to demonstrate the role and investment of the library in

efforts to support students’ academic success and to seek further insight and

feedback into the findings. The results of both surveys and their comparisons

were also used as evidence based data to further shape the strategic plan and

the university library’s assessment plan.

The quantitative results regarding increases in certain areas (library

visits, resource use, and space satisfaction) did not lead to new decisions or

actions but rather acknowledgement that there were areas where the library was

doing well. On the other hand, declining satisfaction results related to

services were indicators that further information should be sought and

potential action taken. Discussion of some of these findings and the actions

taken by the library follow.

Independent of findings from the 2016 survey, the library’s website had

undergone a redesign. Unfortunately, the respondents to the 2016 student survey

found using the library website to be easier than the respondents to the 2018

student survey. This pattern of library website user satisfaction was very important.

Anecdotal evidence from librarians suggested that users were encountering some

difficulties when navigating the library website. The responses to the 2018

survey provided clearer evidence that additional changes are needed. It is

possible that students who participated in the 2016 survey used the library

website before the re-design, so they found the old library website easier to

use. However, even newer students reported challenges with the website. No

immediate actions were taken to revise the webpage, but longer-term planning

includes further redesign of the webpage.

According to Lakos and Phipps (2004), one

example of whether a culture of assessment exists in a library is that the

organization has “relevant data and [that]

user feedback are routinely collected, analyzed, and used to set priorities,

allocate resources, and make decisions” (p. 353). Incorporating users’ feedback

into the decision-making process and making improvements based on the evidence

are part of the effort to strengthen a culture of assessment within the

library. Some of the key findings from the 2016 survey suggested that students

were not satisfied with quiet study space, access to computers, and electrical

outlets. To address these concerns, additional outlets were installed in

several areas in the library. To increase students’ quiet study space, in

Spring 2017 the main library of UIC increased the availability of designated

quiet study space from one floor to two floors in addition to providing more

single study furniture. Further, and again independent of 2016 survey results,

a complete renovation was done at the Library of the Health Sciences between

2017 and 2018, which provided additional study space, more electrical outlets,

a coffee shop, additional computers, additional seating, extended hours,

and—for a short period of time—microwaves.

It would appear that as a result of the space renovations, overall

satisfaction with the library spaces increased. However, access to space

remained a challenge. This is likely due in part to a 5% increase in

undergraduate enrollment and because space issues were already a problem in

2016. Without increasing the actual square footage of the library, the

overcrowding issue remains a challenge to solve. There are also not many more places

to add additional outlets. Findings related to the increase in students’ quiet

space satisfaction are similar to the patterns observed in other studies. For

example, in spite of the issue of insufficient space, other academic libraries

that continued to exert efforts to improve their space by reorganizing study

areas and dealing with noise problems based on users’ feedback did find that

students’ perceptions of quiet space improved over time (McCaffrey, 2019;

McCaffrey & Breen, 2016).

Comparing two surveys to understand the patterns of users’ library

experiences was useful; however, it is not always possible to understand why an

increased or decreased result occurred. McCaffrey (2019) argues that “detailed comparisons between two surveys can be problematic,

particularly when analyzed at a question, user group or dimension level, as

scores can increase or decrease for reasons that may be unknown or difficult to

explain” (p. 72). However, comparisons between two surveys provide a valuable

lesson. Libraries must keep asking core questions and monitoring users’

responses regularly to monitor their experiences and satisfaction with

resources and measure the impact of the library on students’ academic success

over time. In order to capture students’ responses and more accurately measure

the library’s impact on students’ success, the AC2 decided to revise the

response scales, wording, and content (Aksu Dunya

& De Groote, 2019). However, this revision was a very important step in

repeating user surveys over time that provide more meaningful evidence to the

university library staff. In addition, “the effectiveness of the revision” was

supported by the significant increase in the response rate (Aksu Dunya & De Groote, 2019, p. 54). Although the revisions

of both surveys resulted in adjustments to the scales within those surveys to

accurately compare them, the results provide reliable, informative, and

meaningful evidence. This is important because libraries are expected to follow

the steps of the methods rigorously tested and used by researchers (e.g.,

Holmes, & Mergen, 2013; Preston & Colman,

2000).

While the adjustments to the coding and scaling that were made to

compare both surveys were not the primary focus of this paper, it is important

to mention that adjustments to surveys may be needed in subsequent years to

collect the most useful data. This paper demonstrates that institutions should

be prepared from the beginning and be open to adjusting their tools as needed

in order to develop the ideal benchmarking tools that can be used consistently

over time. If a library has data from slightly different surveys (e.g.,

different scales and wording) that requires minor adjustments such as

rescaling, this process should be done carefully by following the methods used by

researchers (e.g., Holmes, & Mergen, 2013;

Preston & Colman, 2000) to make the findings reliable and accurate. The

authors also want to highlight that developing a tool for benchmarking does not

mean that questions need to be identical in each survey. A certain number of

questions can be used for assessing users’ needs related to new services or how

to address different needs based on changes in technology, student enrollment,

or other influences.

This study is unique compared to other studies

reported in the literature because few of those studies have examined how

libraries track and report their impact over time by using local user

experience surveys. By monitoring user trends over time, this study expands

current research on academic libraries’ efforts to use evidence based data for

improvements, decision-making, and future library assessments. Those practices

include reviewing the assessment tool, revising it as needed, and taking action

based on the findings; these are integral to reinforcing a culture of

assessment. These practices provide valuable and meaningful information that

guide librarians who plan to use local surveys to monitor users’ experiences

over time and

determine what to address in their next assessment plan.

Conclusion

Assessing users’ behaviors and satisfaction associated with their use of

library physical spaces, resources, and services should be conducted on an

ongoing basis in order to observe and respond to evolving trends. Determining

how often this type of survey will be conducted and monitored to explore these

trends over time will vary based on the availability of data at libraries and

how the libraries will use the data. The UIC Library plans to conduct student

surveys every other year. A specific set of questions that be asked each time

so that the library can better understand and react to changes in user needs

and interests.

Equally important to conducting assessment is what

academic libraries do in response to the assessment findings. Over time the

findings from surveys can be used as evidence based data to communicate with

various stakeholders for indicating the patterns of users’ behavior, identify

areas for improvement, demonstrate the library’s impact, and develop a deeper

understanding of users. Findings can also be used when developing strategic

plans and a library assessment plan. To accomplish this, the findings from the

surveys need to be carefully reviewed and, when feasible, used as the basis of

responding to users’ needs in order to improve the library spaces, resources,

and services. Not only that, it is critical to re-assess users’ experiences by

comparing present and future survey results with the findings of previous

assessments. This cycle of assessment will be critical for customizing and targeting

services that are useful for the diverse student body served by an academic

library. Establishing a culture of assessment in academic libraries begins with

assessing how users perceive the services and resources provided by the library

and improving users’ experiences based on these findings.

Acknowledgements

We greatly appreciate the support of our colleagues of the University of

Illinois at Chicago’s AC2, who contributed their expertise to the assessment.

We also thank Carl Lehnen and Mary Shultz for

reviewing the manuscript.

References

Aksu Dunya, B.,

& De Groote, S. (2019). Revision of an academic

library user experience survey. Performance Measurement and Metrics, 20(1),

48–59. https://doi.org/10.1108/PMM-10-2018-0026

Allen, L., Baker, N., Wilson, J., Creamer, K., & Consiglio, D. (2013). Analyzing the MISO data: Broader

perspectives on library and computing trends. Evidence Based Library and

Information Practice, 8(2), 129–138. https://doi.org/10.18438/B82G7V

Anderson, L. (2016). Library website visits and

enrollment trends. Evidence Based Library and Information Practice, 11(1),

4–22. https://doi.org/10.18438/B8F918

Association of Research Libraries. (n.d.). ARL

Statistics. Retrieved from https://www.arlstatistics.org/repository

Association of Research Libraries (n.d.). LibQUAL+ 2018 survey. Retrieved from http://www.libqual.org/publications

Cohen, D. (2019, May 26). The books of college

libraries are turning into wallpaper. The Atlantic. Retrieved July 25,

2019, from https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2019/05/college-students-arent-checking-out-books/590305/

De Groote, S. L., Hitchcock,

K., & McGowan, R. (2007). Trends in reference usage

statistics in an academic health sciences library. Journal of the Medical

Library Association: JMLA, 95(1), 23–30. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1773032/

Dennis, M., Greenwood, J., & Watson, A. (2013). LibQUAL revisited: Further analysis of qualitative and

quantitative survey results at the University of Mississippi. Journal of

Academic Librarianship, 39(6), 512–516. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2013.08.009

Farkas, M., Hinchliffe, L., & Houk,

A. (2015). Bridges and barriers: Factors influencing a culture of assessment in

academic libraries. College & Research Libraries, 76(2),

150–169. https://doi.org/10.5860/crl.76.2.150

Greenwood, J. T., Watson, A. P., & Dennis, M.

(2011). Ten years of LibQual: A study of qualitative

and quantitative survey results at the University of Mississippi 2001-2010. Journal

of Academic Librarianship, 37(4), 312–318. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2011.04.005

Hinchliffe, L. J. (2015). Osservatorio:

Library assessment and user surveys in academic librarianship in the United

States. AIB Studi, 55(2), 247–257. https://doi.org/10.2426/aibstudi-11198

Holmes, D. S.,

& Mergen, A. E. (2013). Converting survey results

from four-point to five-point scale: A case study. Total Quality Management

and Business Excellence, 25(1–2), 175–182. https://doi.org/10.1080/14783363.2013.799330

Lakos, A., & Phipps, S. (2004). Creating a culture of assessment: A

catalyst for organizational change. portal: Libraries and the Academy, 4(3),

345–361. https://doi.org/10.1353/pla.2004.0052

Lee, M., Ritterbush, J.,

& Sivigny, R. (2010). Reference at the commons: A

case study. Reference Services Review, 38(1), 81–89. https://doi.org/10.1108/00907321011020743

Liebst, A., & Feinmark, D. (2016). Tools of

academic library assessment: The user survey. Journal of Library

Administration, 56(6), 748–755. https://doi.org/10.1080/01930826.2016.1199144

Matthews, J. R. (2007). Library assessment in

higher education. Westport, Conn.: Libraries Unlimited.

McCaffrey, C. (2019). Transforming the university

library one step at a time: A ten year LibQUAL +

review. New Review of Academic Librarianship, 25(1), 59–75. https://doi.org/10.1080/13614533.2018.1511438

McCaffrey, C., & Breen, M. (2016). Quiet in the

library: An evidence-based approach to improving the student experience. portal,

16(4), 775–791. https://doi.org/10.1353/pla.2016.0052

Mierzecka, A., & Suminas, A. (2018). Academic

library website functions in the context of users’ information needs. Journal

of Librarianship and Information Science, 50(2), 157–167. https://doi.org/10.1177/0961000616664401

Montgomery, S. E. (2014). Library space assessment: User learning

behaviors in the library. Journal of Academic Librarianship, 40(1),

70–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2013.11.003

Norton, H. F., Tennant, M. R., Edwards, M. E., & Pomputius,

A. (2018). Use of annual surveying to identify technology trends and improve

service provision. Journal of the Medical Library Association, 106(3),

320–329. https://doi.org/10.5195/jmla.2018.324

Oberlander, C., Miller, B., Mott, E., & Anderson,

K. (2019, May 3). How data improved our library space. The Chronicle of

Higher Education. Retrieved from https://www.chronicle.com/interactives/20190505-Oberlander

Ojennus, P., & Watts, K. A.

(2017). User preferences and library space at Whitworth

University Library. Journal of Librarianship and Information Science, 49(3),

320–334. https://doi.org/10.1177/0961000615592947

Preston, C. C., & Colman, A. M. (2000). Optimal

number of response categories in rating scales: Reliability, validity,

discriminating power, and respondent preferences. Acta Psychologica,

104(1), 1–15.

https://doi.org/10.1016/S0001-6918(99)00050-5

Schmider, E., Ziegler, M., Danay, E., Beyer, L., &

Bühner, M. (2010). Is it really robust?

Reinvestigating the robustness of ANOVA against violations of the normal

distribution assumption. Methodology, 6(4), 147–151. https://doi.org/10.1027/1614-2241/a000016

Scoulas, J. M., & De Groote, S. L. (2019). The library’s impact on university students’ academic success and

learning. Evidence Based Library and Information Practice, 14(3),

2–27. https://doi.org/10.18438/eblip29547

Taylor, M., & Heath, F. (2012). Assessment and

continuous planning: The key to transformation at the University of Texas

Libraries. Journal of Library Administration, 52(5), 424–435. https://doi.org/10.1080/01930826.2012.700798

Thompson, B., Cook, C., & Health, F., (2000) The LibQual+ gap measurement model: the bad, the ugly, and the

good of gap measurement. Performance Measurement and Metrics, 1(3),

165–178.

https://doi.org/10.1108/EUM0000000007216

Voorbij, H. (2012). The use of LibQUAL+ by European

research libraries. Performance Measurement and Metrics, 13(3),

154–168. https://doi.org/10.1108/14678041211284704

Appendix A

2016 Student Survey

I have read the “Agreement to Participate” document and agree to

participate in this research.

o Yes

o No

In the past year, have you visited the library at your campus site for

study or research?

o Yes

o No

o I am an online student only

How satisfied are you with the quiet study space at your library?

o Very satisfied

o Satisfied

o Neutral

o Dissatisfied

o Very dissatisfied

o I do not use quiet space in the library

How satisfied are you with the collaborative/group space at your

library?

o Very satisfied

o Satisfied

o Neutral

o Dissatisfied

o Very dissatisfied

o I do not use group space in the library

How satisfied are you with the computers available at your library?

o Very satisfied

o Satisfied

o Neutral

o Dissatisfied

o Very dissatisfied

o I do not use the computers in the library

If you study in places other than your library, what do you like about

those spaces? [Check all that apply.]

o More study space

o Quieter

o Food/drinks are sold here

o Equipment or software that I need are available

o Other (please specify):___________________

o I do not study in spaces other than my library

In the past year, have you used the library books, e-books, databases,

journal articles, or other library resources?

o Yes

o No

How satisfied are you with the library resources you have used in the

past year?

|

|

Have not used this |

Very satisfied |

Satisfied |

Neutral |

Dissatisfied |

Very dissatisfied |

|

Textbooks on reserve

in the Library |

o |

o |

o |

o |

o |

o |

|

Books (other than

required textbooks) |

o |

o |

o |

o |

o |

o |

|

E-books (other than

required textbooks) |

o |

o |

o |

o |

o |

o |

|

E-journals |

o |

o |

o |

o |

o |

o |

|

Databases |

o |

o |

o |

o |

o |

o |

|

Streaming videos |

o |

o |

o |

o |

o |

o |

|

Online patient care

tools |

o |

o |

o |

o |

o |

o |

|

DVDs on reserve |

o |

o |

o |

o |

o |

o |

|

Other, please specify |

o |

o |

o |

o |

o |

o |

What two specific library resources have you used the most in the past

year?

Please rank up to 3 resources you use most often for research projects,

1 being the most important (where you go first)

o Search box on the library website

o Library subject/research guides

o Library of the Health Sciences website (Chicago, Peoria, Rockford, or

Urbana)

o The Health Sciences Gateway

o Database A-Z list

o Google or some other search engine (Bing, Yahoo, etc.)

o Wikipedia

o Academic search engine such as Google Scholar

o Blackboard

o Other (Please specify):_____________________

Think about your satisfaction with the library services you have used in

the past year. How satisfied were you with each service?

|

|

Have not used this |

Very satisfied |

Satisfied |

Neutral |

Dissatisfied |

Very dissatisfied |

|

A class session where

a librarian taught research skills for a specific assignment |

o |

o |

o |

o |

o |

o |

|

A library workshop

that teaches how to use online resources |

o |

o |

o |

o |

o |

o |

|

Assistance from staff

in the library |

o |

o |

o |

o |

o |

o |

|

Ask a librarian by

IM/chat, phone, or email |

o |

o |

o |

o |

o |

o |

|

A research consultation

with a librarian (scheduled appointment) |

o |

o |

o |

o |

o |

o |

|

Request a book or

article from another library |

o |

o |

o |

o |

o |

o |

|

Specialized research

assistance from the subject librarian for my department/college |

o |

o |

o |

o |

o |

o |

|

Group study rooms in

the library |

o |

o |

o |

o |

o |

o |

Think about how you used the library website in the past year. How easy

was it to use each feature below?

|

|

Have not used this |

Very easy |

Easy |

Neutral |

Difficult |

Very difficult |

|

Find a book at the

University |

o |

o |

o |

o |

o |

o |

|

Login to my account to

renew a library book or check the status of a request |

o |

o |

o |

o |

o |

o |

|

Search for journal

articles on my topic |

o |

o |

o |

o |

o |

o |

|

User a library

subject/research guide to find material by subject |

o |

o |

o |

o |

o |

o |

|

Find films, videos, or

online images at the university |

o |

o |

o |

o |

o |

o |

|

Request a book or

article from another library |

o |

o |

o |

o |

o |

o |

|

Ask a librarian for

assistance by email or IM chat |

o |

o |

o |

o |

o |

o |

|

Make an appointment

for research help |

o |

o |

o |

o |

o |

o |

|

Book a group study

room online |

o |

o |

o |

o |

o |

o |

|

Some other activity

(please specify): [ ] |

o |

o |

o |

o |

o |

o |

As part of your online course(s), have you used the university library

e-books, databases, journal articles or other library resources or services for

assignments or other course-related activities?

o Yes

o No

In the past year, have you used the library website to find e-books,

databases, e-journals, or other library resources?

o Yes

o No

Think about the library services you used in the past year in your

online program. How satisfied are you with each service?

|

|

Have not used this |

Very satisfied |

Satisfied |

Neutral |

Dissatisfied |

Very dissatisfied |

|

Requesting an article

from the university library or another library |

o |

o |

o |

o |

o |

o |

|

Online access to

full-test articles and e-books |

o |

o |

o |

o |

o |

o |

|

Online IM/chat

research help |

o |

o |

o |

o |

o |

o |

|

Telephone research

help |

o |

o |

o |

o |

o |

o |

|

Virtual consultation

with a librarian |

o |

o |

o |

o |

o |

o |

|

Online workshops about

library research (e.g., finding books, journals, requesting electronic

materials, finding literature and journal articles) |

o |

o |

o |

o |

o |

o |

|

Self-paced tutorials

about library research |

o |

o |

o |

o |

o |

o |

When should the library offer virtual consultations or online workshops

with a librarian to provide assistance with library research? Select you most

preferred time.

o 8am to 12 pm CST (Monday-Friday)

o 12-4 pm CST (Monday-Friday)

o 4-8 pm CST (Monday-Friday)

o 8 pm to 12 am CST (Monday-Friday)

o Weekends during the day

o Live virtual services not needed

How would you spend money to improve the library? Please select the two most important items.

o Longer hours

o More comfortable furniture

o More computers

o More online resources (ebooks, ejournals, databases, etc)

o More electrical outlets

o More individual desks

o More print books

o More quiet/silent study spaces

o More whiteboards

o Other (Please specify):_______________

Thinking about your overall experience with the library, what is one

thing that you would like us to know to improve your experience?

Appendix B

2018 Student Experience Survey

I have read the “Agreement to Participate”

document and agree to participate in this research.

o Yes

o No

Last semester, how often did you visit the

university library?

|

|

Daily |

Multiple days in a

week |

Once a week |

Once a month |

Never |

|

In person |

o |

o |

o |

o |

o |

|

Online |

o |

o |

o |

o |

o |

How satisfied are you with the library spaces

below at your library?

|

|

Very satisfied |

Satisfied |

Dissatisfied |

Very dissatisfied |

I don’t use this space

in the library |

|

Quiet study spaces |

o |

o |

o |

o |

o |

|

Collaborative study

spaces |

o |

o |

o |

o |

o |

|

Group study rooms |

o |

o |

o |

o |

o |

|

Computer areas |

o |

o |

o |

o |

o |

If you study in places other than the university library, what do you

like about those spaces?

[Check all that apply]

o More study space

o Quieter study space

o Food/drink availability

o Software availability

o Equipment (e.g., computer, printer, scanner, etc.) availability

o Longer hours

o More comfortable furniture

o I can find a seat

o I prefer to study at home

o Other (Please specify) [ ]

Last semester, how often did

you use each of the library resources below?

|

|

Daily |

Multiple days in a

week |

Once a week |

Once a month |

Never |

|

Journal articles |

o |

o |

o |

o |

o |

|

Subject specific

databases |

o |

o |

o |

o |

o |

|

Print books from the

stacks |

o |

o |

o |

o |

o |

|

Textbooks on reserve |

o |

o |

o |

o |

o |

|

Electronic books |

o |

o |

o |

o |

o |

|

Library Subject &

Course Guides |

o |

o |

o |

o |

o |

|

Special Collections

& University Archives |

o |

o |

o |

o |

o |

|

Digital images |

o |

o |

o |

o |

o |

|

Streaming media |

o |

o |

o |

o |

o |

|

DVDs on reserve |

o |

o |

o |

o |

o |

|

Patient care tools |

o |

o |

o |

o |

o |

Please indicate the relative importance

of each of the library resources/services for your research or coursework.

|

|

Very important |

Important |

Somewhat important |

Not at all important |

I don’t use this

tool/service |

|

Journal articles |

o |

o |

o |

o |

o |

|

Subject specific

databases |

o |

o |

o |

o |

o |

|

Print books from the

stacks |

o |

o |

o |

o |

o |

|

Textbooks on reserve |

o |

o |

o |

o |

o |

|

Electronic books |

o |

o |

o |

o |

o |

|

Library Subject &

Course Guides |

o |

o |

o |

o |

o |

|

Special Collections

& University Archives |

o |

o |

o |

o |

o |

|

Digital images |

o |

o |

o |

o |

o |

|

Streaming media |

o |

o |

o |

o |

o |

|

DVDs on reserve |

o |

o |

o |

o |

o |

|

Patient care tools |

o |

o |

o |

o |

o |

|

Library instruction

arranged by your professor |

o |

o |

o |

o |

o |

|

Library workshops that

you self-selected to attend |

o |

o |

o |

o |

o |

|

Other (Please specify) |

o |

o |

o |

o |

o |

How easy is it to use the university library website for the

services below?

|

|

Very easy |

Easy |

Difficult |

Very difficult |

I don’t use this

service |

|

Finding journal

articles using the search box on the library home page |

o |

o |

o |

o |

o |

|

Finding an e-book

using the search box on the library home page |

o |

o |

o |

o |

o |

|

Finding a print book

using the search box on the library home page |

o |

o |

o |

o |

o |

|

Accessing a database

to search for articles and other scholarly materials |

o |

o |

o |

o |

o |

|

Requesting a print

book from another library |

o |

o |

o |

o |

o |

|

Requesting an article from

another library |

o |

o |

o |

o |

o |

|

Logging into my

library account to renew a book |

o |

o |

o |

o |

o |

|

Asking for help from a

librarian by IM/chat |

o |

o |

o |

o |

o |

|

Using library Subject

& Course Guides to access materials by subject |

o |

o |

o |

o |

o |

|

Finding

media (e.g., films, videos, online images, etc.) |

o |

o |

o |

o |

o |

|

Booking a group study

room online |

o |

o |

o |

o |

o |

|

Other (Please specify) |

o |

o |

o |

o |

o |

How likely are you to

recommend the following library services to another student?

|

|

Very likely |

Likely |

Unlikely |

Very unlikely |

I don’t use this

service |

|

One on one research

consultation with a librarian |

o |

o |

o |

o |

o |

|

Library workshops

about library research (e.g., finding resources, requesting materials, etc.) |

o |

o |

o |

o |

o |

|

IM/Online chat

research help |

o |

o |

o |

o |

o |

|

E-mail research help |

o |

o |

o |

o |

o |

Suppose you had funding to improve the university library. Please select

up to three of your most important priorities from the list below.

o Access to more online journals

o Access to more books (e-books, print books, textbooks)

o More computers

o More quiet study space

o More group study space

o More electrical outlets

o More whiteboards

o More drink/food options

o Additional comfortable furniture

o Other (Please list) [ ]

Think about your overall library experience at the institution, please

tell us about your experiences with the library that positively impacted your

coursework or research.

|

|