Research Article

An Exploratory Study of Accomplished

Librarian-Researchers

Marie R. Kennedy

Serials & Electronic

Resources Librarian

Loyola Marymount University

Los Angeles, California,

United States of America

Email: marie.kennedy@lmu.edu

Kristine R. Brancolini

Dean of the Library

Loyola Marymount University

Los Angeles, California, United States of America

Email: brancoli@lmu.edu

David P. Kennedy

Senior Behavioral and Social

Scientist

RAND Corporation

Santa Monica, California, United States of America

Email: davidk@rand.org

Received: 16 Sept. 2019 Accepted: 3 Jan. 2020

![]() 2020 Kennedy, Brancolini, and Kennedy. This

is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/), which

permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

2020 Kennedy, Brancolini, and Kennedy. This

is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/), which

permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

DOI: 10.18438/eblip29655

Abstract

Objective – This work explores potential factors that may contribute to a

librarian becoming a highly productive researcher. An understanding of the

factors can provide evidence based guidance to those at the beginning of their

research careers in designing their own trajectories and to library

administrators who seek to create work conditions that contribute to librarian

research productivity. The current study is the first to explore the factors

from the perspective of the profession’s most accomplished librarian-researchers.

Methods – This

exploratory and descriptive study recruited 78 academic librarians identified

as highly productive researchers; 46 librarians participated in a survey about

their professional training and research environments, research networks, and

beliefs about the research process. Respondents supplied a recent CV which was

coded to produce a research output score for the past 10 years. In addition to

fixed-response questions, there were five open-ended questions about possible

success factors. All data were analyzed with descriptive statistics and tests

of significance correlations.

Results – Accomplished

librarian-researchers have professional training backgrounds and research

environments that vary widely. None is statistically associated with research

output. Those with densely connected networks of research colleagues who both

know each other and do research together is significantly related to research

output. A large group of those identified in the research networks are “both

friend and colleague” and offer each other reciprocal support. In open-ended

questions, respondents mentioned factors that equally span the three categories

of research success: individual attributes, peers and community, and

institutional structures.

Conclusion – The authors found that that there are many paths to becoming an

accomplished librarian-researcher and numerous factors are conducive to

achieving this distinction. A positive research environment includes high

institutional expectations; a variety of institutional supports for research;

and extrinsic rewards, such as salary increases, tenure, promotion, and

opportunities for advancement. The authors further conclude that a librarian’s

research network may be an important factor in becoming an accomplished librarian-researcher.

This finding is supported by both the research network analysis and responses

to open-ended questions in which collaboration was a frequent theme.

Introduction

The authors of this article investigated the

professional training and environment, research networks, and attitudes about

research of accomplished librarian-researchers. The authors consulted a group

of librarian-researchers who represent the high end of research productivity to

explore potential contributors. This is the first study that examines these

possible contributors for the population of the most productive librarian-researchers.

In academia, the proxy for productivity is publication activity, so the authors

identified academic librarian-researchers who have written the highest number

of library and information science (LIS) publications over the past 10 years.

The authors analyzed the resulting data to learn if there are commonalities

among these librarian-researchers.

Problem Statement

Librarians at the

outset of their research careers can benefit from understanding factors that

contributed to the productivity of accomplished librarian-researchers, such as

professional training and research environment, social supports in the research

network, and beliefs about and the practice of the research process. Insight

into these factors can help them to imagine their own career trajectories. To

that end, this study is guided by two research questions:

1.

What

are the factors that accomplished librarian-researchers identify as having

contributed to their becoming a productive researcher?

2.

What

are the compositional commonalities of the research networks of these

librarian-researchers with a high level of research output?

Literature Review

In the LIS literature there has been a recent focus on research

productivity among librarian-researchers, including the factors that may be

related to the successful completion of research projects. There are three

areas of concern in this study related to factors that may align with

productivity of librarian-researchers in an academic setting: professional

training and research environment; research network; and beliefs about and the

practice of the research process. This section addresses literature in those

areas.

Professional Training and Research Environment

Many academic librarians are actively conducting and disseminating

the results of their original research. Librarians author the majority of

articles in LIS journals (Chang, 2016), including the profession’s most

highly-regarded journals (Galbraith, Smart, Smith, & Reed, 2014). For

example, they account for the majority of the authors in the Journal of Academic Librarianship (Luo

& McKinney, 2015). Despite this success, an often-cited barrier to

librarian research productivity is the lack of research training in the LIS

master’s curriculum. Lili Luo found in her 2010 review of the degree

requirements for the 49 American Library Association-accredited LIS programs

that 61% list research methods as a required course (Luo, 2011). However, there

is not a standard research methods curriculum at the master’s degree level, so

the training offered across the programs varies in content and depth. In

addition to lack of research training, librarians cite other barriers,

including lack of research confidence, lack of a research community, lack of

institutional support, and lack of time (Kennedy & Brancolini, 2018).

Despite these barriers, researchers have found that some academic librarians

are intrinsically motivated to move forward with a research agenda, noting reasons

such as personal satisfaction, intellectual curiosity, and the desire to

contribute to the profession (Fennewald, 2008; Hollister, 2016; Perkins &

Slowik, 2013). Related to those intrinsic motivators, Watson-Boone (2000) noted

that academic librarian authors’ efforts “improve their own practice and

further develop their own levels of expertise” (p. 91).

The employment environment may also contribute to the productivity

of librarian-researchers. In a study of the relationship between, faculty

status and research productivity, Galbraith et al. (2014) examined the

authorship of articles published in the top 23 LIS journals. They found that

42% of the articles were written by academic librarians. Of those, 65% worked

at libraries with faculty status and tenure.

Hoffmann, Berg, and Koufogiannakis

(2014) identified 42 empirical research articles on productivity for librarian

and non-librarian practitioner-researchers – such as doctors, nurses, and

social workers. Based on a definition of research productivity as “completion

of research activities and subsequent dissemination of research findings” (p.

15), the authors conducted a content analysis of these articles and identified

16 factors that they believe contribute to research productivity, which cluster

into 3 broad categories: individual attributes, peers and community, and

institutional structures and supports. They used these categories to develop a

survey administered to 1,653 librarians who worked at the 75 Canadian Research

Knowledge Network and were likely conducting research as part of their job

responsibilities (Hoffmann, Berg, & Koufogiannakis, 2017). In the study, Hoffmann et al. calculated a research productivity score and looked for statistical

correlations with specific success factors. They did not identify a single

factor within the three categories as the main statistical contributor to

research productivity, leading them to conclude that “an environment that embraces all

three areas, by encouraging individual attributes, foster peer and community

interaction, and providing institutional supports, will be likely to promote

research productivity among librarians” (p. 116).

Research Networks

Research “peers and community” networks are important contributors

to research productivity. A successful librarian-researcher has built his or

her own personal network of social contacts over the course of a career. These

networks can be measured using the method of social network analysis which is

designed to describe the relationships between those social contacts (Borgatti,

Everett, & Johnson, 2013; Wasserman & Faust, 1994). Social network

analysis provides a conceptual structure and measures for examining the

relationships in a research network.

The authors identified only one publication that uses social network

analysis to measure the research networks of librarian-researchers. That

singular study investigated the personal research networks of novice

librarian-researchers (Kennedy, Kennedy, & Brancolini, 2017). The approach

to measurement used in that analysis is the personal

or egocentric network approach, since

the focus of study was to understand the social ties surrounding an

independently sampled set of focal individuals (McCarty, 2002). In that

research the authors relied on those focal individuals (referred to as egos) to report on the relationships

with those they identified as being part of their research network (referred to

as alters) and their perceptions of

the relationships between all possible pairs of those in the network, including

themselves (Krackhardt, 1987). Network composition (the types of people in the

network) was measured by calculating the proportion of network ties with a

certain characteristic, such as the proportion of network members who offer

research assistance (as described in Crossley et al., 2015). Network structure

(interconnections among network members) was assessed by calculating the ratio

measure of the number of connections among network members compared to the

total possible number of ties (called density)

(as described in Crossley et al., 2015; McCarty, 2005; Wasserman & Faust,

1994).

The authors did not find any examples in the literature of

investigations of the networks of accomplished librarian-researchers.

Beliefs about and

the Practice of the Research Process

As the literature in the field of library

and information science (LIS) has now well described the barriers to conducting

research, researchers have turned their attention to the influences on research

success. The recent literature has focused on supportive structures from an

administrator viewpoint (Berg, Jacobs, & Cornwall, 2013; Perkins &

Slowik, 2013; Sassen & Wahl, 2014; Smigielski, Laning, & Daniels, 2014)

as well as from a practitioner-researcher perspective (Fiawotoafor, Dadzie, &

Adams, 2019; Meadows, Berg, Hoffmann, Gardiner, & Torabi, 2013; Vilz &

Poremski, 2015).

Methods

The

authors developed a survey to elicit information about the respondents’

professional training, their research networks, their beliefs about research,

and their research practices. The survey included questions about research

beliefs and practice adapted from Hoffmann et al. (2017). The survey also

included five open-ended questions about factors contributing to research

productivity designed to elicit a more comprehensive understanding of the

factors directly from the accomplished librarian-researchers. The authors also

measured productivity of participants directly by collecting and coding full

and recent CVs of each participant rather than self-reports, which can be unreliable

(Hoffmann et al., 2017).

Study Population

A

requirement of this research is identifying the most productive

librarian-researchers. There is no database kept in the United States at the

national level of academics classified by their field of specialty, as in Italy

(Abramo, D’Angelo, & Di Costa, 2019), so the authors needed to create a

list of those accomplished librarian-researchers for this work. The list was

formed from two sources of data.

The

first source of data was drawn from Clarivate’s Web of Science (Clarivate,

2018) and focused on librarians working at public and private university

libraries in the United States of America that are members of the Association

of Research Libraries (ARL) (2019), which are research-intensive institutions.

Using the Web of Science Social Science Citation Index, the authors conducted

advanced searches for each of the 99 ARL libraries (using the Organization

Enhanced field tag), combined with the topic of “library” and the Web of

Science category, “Information science library science,” including all document

types, and published from the time span of 2007 to 2018. From each library the

authors of those publications were ranked by number of items published. Those

with five or more items published were highlighted. The researchers conducted

an internet search for each of those authors, to verify if the person was a

practicing librarian; if so, they were included in the set, resulting in 39

librarians.

The

authors supplemented this list with a second source of data: a list of

researchers not necessarily affiliated with ARL Libraries provided by the first

author of an article about worldwide contributors to the literature of library

and information science (Walters & Wilder, 2015). This study identified the

top librarian authors in the field (based on a harmonic weight of authors

publishing in 31 LIS journals). From this data the authors selected the top 50

from the United States and merged them with their Web of Science set. There

were 10 names included on both lists, producing a total of 79 unique

librarians, 60 from ARL member libraries and 19 from other academic

libraries.

Recruitment and

Survey Dissemination

After

receiving approval of the protocol from the Institutional Review Board, the

authors sent an initial email with the request for participation with a link to

a personalized survey. Recruitment emails were successfully sent to 74 of the

78 librarian-researchers. Three were not able to be contacted because their

emails were returned as undeliverable and one was unintentionally omitted from

recruitment. One follow-up email was sent to those who did not respond to the

initial request. The recruitment email may be found as Appendix A. A $100 USD

gift card was offered to each respondent who completed the survey and supplied

their CV.

Survey Design and

Measures

The

authors designed the survey around three areas of concern related to research

output: professional training research environment; the research network of the

respondent; and beliefs about and the practice of the research process. The

survey was constructed using EgoWeb 2.0 (2015), the freely-available open

source tool for network data collection. The survey was administered using a

personalized URL.

Professional Training and Research Environment

Respondents

were asked a series of questions that assessed their graduate-level educational

background, including the year in which their LIS degree was completed and if

they wrote a thesis while completing their LIS degree or another master’s

degree (yes/no). Respondents were also asked if they believed their LIS degree

prepared them to read and understand research-based literature (yes/no) and if

they believe it prepared them to conduct original research (yes/no). To assess

experience with research method training, respondents were presented with a

list of educational activities about research methods and asked to mark all in

which they have ever participated. The list includes: formal master’s degree

LIS course; formal master’s degree non-LIS course; formal doctoral LIS course;

formal doctoral non-LIS course; continuing education program; staff development

program; self-education, and; none of these. To assess respondents’ early and

current research support, respondents were presented with a list of support

options and asked to identify which were available them and which they had

used. The options include: release time; short-term pre-tenure research leave;

sabbaticals for librarians; travel funds (full); travel funds (partial);

research grants; formal mentorship; informal mentorship; research design

consultant; workshops.

To

measure mentoring experiences, respondents were asked if they had ever

participated in any formal or informal mentorship programs. Respondents were

also asked if they had achieved tenure at a previous institution and/or at

their current institution and their rank. The respondents were then asked one

question to assess if they conducted their early research either (1) on their

own, with partners who were (2) more, (3) less or (4) equally experienced, or

with research teams that were composed of (5) mostly novice researchers or (6)

mixed novice and experienced researchers. They were also asked this same

question about their current research coupled with an open-ended question

asking them to describe their current research. Finally, respondents were asked

two open-ended questions, one prompting the participant to note anything else

about their professional training

over the last 10 years that they believe may have contributed to their

productivity, and the other prompting to note anything about their research environment over the last 10

years.

Research Network

After

answering questions about their own research experiences, respondents were

asked about their research networks using standard ego-centered network data

collection procedures (Crossley et al., 2015; McCarty et al., 2019). The first

step, network elicitation, prompted

respondents to name the people (up to 40) with whom the respondents have

research interactions (their “alters”). Next, “name interpreter” questions were

asked about each alter to produce measures of network composition. Questions included how often the respondent

interacted with alters over the past 30 days, and how often they discussed

research during those interactions. Respondents also classified each alter as a

personal friend, professional colleague, or both friend and colleague and

reported on their advice/help relationship with each alter (the respondent

usually asks for advice/help, usually offers advice/help, or the research

interactions include asking for and giving help in equal amounts). Respondents

reported if alters were local to the respondents’ workplace, and their mode of

usual communication with each alter (in person, online, phone, etc.). Finally,

respondents were asked if they had a formal mentoring relationship with each

alter and if they mentored the alter or the alter mentored the respondent.

After each name interpreter question, respondents were asked one question to

measure network structure.

Respondents were asked to evaluate the relationship between each unique pair of

alters: if they know each other and, if yes, if they had research interactions.

The section of the survey ends with an open-ended question to discover if there

is anything else about the people in the current research network that may have

contributed to the productivity of the respondent.

Beliefs about and the Practice of the Research Process

The

last section asked respondents to evaluate twenty-eight statements regarding

beliefs about the research process with a yes or no response to

report whether it generally applies to them or not. The statements are a subset

from the survey administered by Hoffmann et al. (2017) to academic librarians

employed by Canadian research libraries. To facilitate comparisons with this

previous study, the statements used as much of the verbatim language as the

original question as possible. The final question prompted the respondent to

think back on their entire career and list the three factors that have been the

most significant to them becoming a productive librarian-researcher (open-ended

text response).

The

informed consent and full questionnaire may be found as Appendix B.

Research Productivity

Research productivity was measured based on a review of each

participant’s current CV. At the completion of the survey, participants were

asked to forward their CV to the authors, who reviewed the research output over

the last 10 years. The authors used the counting and scoring scheme developed

by Hoffmann et al. (2017, p. 107), outlined in Table 1. The score was not

adjusted for multi-authored pieces; if the output was listed on a CV, it was

counted as one item, regardless of author position.

Table 1

Scores Used for Research Output

|

Output type |

Score |

|

Poster |

0.5 |

|

Presentation |

1 |

|

Conference proceeding |

1 |

|

Non-peer-reviewed article |

3 |

|

Book chapter |

5 |

|

Edited book |

6 |

|

Peer-reviewed article |

9 |

|

Authored book |

10 |

Items

such as book reviews, creative writing, teaching a class, moderating a

conference panel, editing a journal, or writing an evidence summary were not

included as research output. Although these works are scholarly in nature, they

were excluded because they are not dissemination of original research. For this

analysis, if a presentation was determined to be part of a participant’s job

performance (for example, a webinar about how to use a library resource), it

was not scored. The authors do include the following, as done by Hoffmann et

al. (2017): poster; presentation; conference proceeding; non-peer-review

article; book chapter; edited book; peer-reviewed article; authored book.

Analysis

Descriptive

statistics (counts and percentages for categorical / nominal responses, means

and standard deviations for continuous measures) were calculated for each

individual survey item. The final research output score for each participant

was calculated by multiplying the number of types of output and their related

scores, then adding all scores together.

For

questions about the research network, descriptive measures of network composition were calculated from

the raw responses about alter characteristics and relationships with alters

provided by respondents. First, network

size was calculated at the participant level by counting the total number

of alters provided by each participant and then averaged across all

participants. Measures of network composition were produced at the respondent

level as well as across all respondents’ networks. Counts of different types of

network members were produced for each respondent (e.g. professional

colleagues, mentees, etc.). Also, measures of percent of different types of

network members were produced for the entire sample of alters by counting the

total number of network members with the characteristic divided by the total

number of alters named by participants. The measure “density” was produced to

measure the network structure of each

respondent’s ego-centric network data using statistical software R’s “igraph”

package (Borgatti, Everett, & Johnson, 2013; Csárdi, 2019). Density is the

ratio of observed relationships in a network to the total number of possible

network ties and rages from zero (no observed ties) to one (all possible ties

exist). A density measure was produced for the tie between alters who knew each

other and did research together.

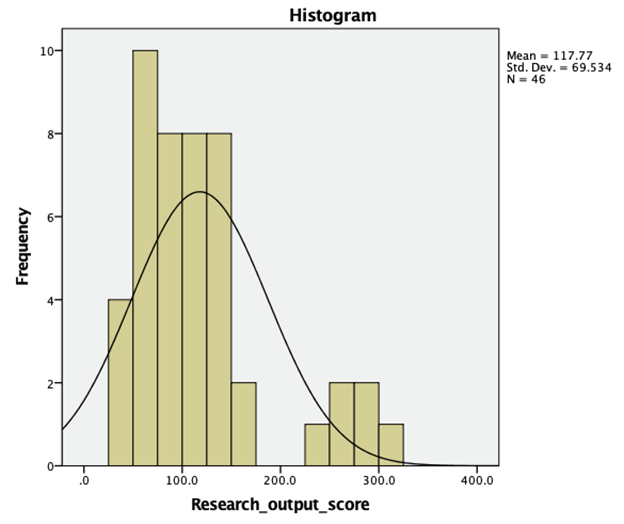

The

authors conducted bivariate correlation tests to test the association between

survey responses and research output. First, a Shapiro-Wilk test was conducted

in SPSS (Version 24) to test for data normality for the research output scores

and it was determined that the distribution of research output scores is not

normal (p = .00). The histogram for

the research output scores is included in Appendix C. The following findings,

then, use the non-parametric tests Mann-Whitney U and Spearman’s rho, depending

on the nature of the variables tested. The significance of correlations was

evaluated at the 95% confidence level (p < .05).

Coding of Open-ended Questions

The authors coded

responses the four open-ended questions, using codes initially informed by the

research success factors identified by Hoffmann et al. (2014, 2017). The

initial code definitions were iteratively modified and refined to fit the data,

including differentiating factors that are close to one another. For example,

the authors split Education from Experience, to create two codes; and they

wrote definitions for Intrinsic Motivations to differentiate them from

Personality Traits. The authors also created a new code for Job-related

Characteristics or Opportunities, to account for respondents’ comments about

the nature of their work and its contribution to their research. They also

eliminated one of the factors, Departmental/Institutional Qualities, as it was

impossible to differentiate it from Organizational Climate.

The

research success factors provided a useful framework for coding the

respondents’ answers to open-ended questions and validated the categories and

success factors identified by Hoffmann et al. (2017). New codes were easily

placed within the three categories: Individual Attributes, Peers and Community,

and Institutional Structures and Supports. The codebook is Appendix D, with

example text from the survey respondents.

Results

A

total of 46 participants completed the survey and provided their CVs, for a

58.97% completion rate. Of the 46 respondents, 70% currently work in ARL member

libraries and 30% in other academic libraries.

Survey

Professional Training and Research Environment

Other

than holding a LIS master’s degree (held by all but one of the 46 respondents),

there was diversity in professional training and research environment among

respondents. There was a range of types of graduate degrees and a mix of degree

types. There were 19 respondents who hold no additional degree beyond the LIS.

Another 15 respondents hold a second master’s degree, while 12 respondents hold

a doctoral-level degree, 9 of those with a second master’s degree and 3 without

an additional master’s degree.

The

professional age of the group varies, with degree completion ranging from 1970

to 2015. Of the responses received, 1 respondent completed the LIS degree in

the 1970s, 5 completed it in the 1980s, 17 completed it in the 1990s, 19 completed

the degree from 2000-2010, and 3 completed it since 2011. On average, this

group has held their professional LIS credentials for about 20 years (SD = 8.62).

There

is strong agreement in the group related to their belief that their LIS

Master’s degree did not adequately prepare them to conduct original research;

38 of the 46 do not believe their degree provided research-readiness. On the

whole, the group participates minimally in educational activities about

research methods, reporting about three activities, with self-education being

the most popular, noted by 41 of the 46 respondents.

Only 1

of the 45 respondents with a LIS master’s degree wrote a thesis while

completing the LIS degree. Of the 26 who reported holding an additional

master’s degree, 12 wrote a thesis while completing that degree (46.15%). Of

the 45 respondents, 26 believe that their LIS master’s degree adequately

prepared them to read and understand research-based literature, but only 8

believe that their LIS master’s degree adequately prepared them to conduct

original research.

The

group notes the availability and use of partial travel funds from their

institutions or libraries, with that option present for 39 of the 46

respondents. The support option least offered was short-term pre-tenure

research leave, with only 11 respondents reporting it; 5 of those 11 had taken

advantage of that support.

The

group has participated more often in informal mentoring opportunities, both as

mentor (33 of 46) and mentee (30 of 46), than formal mentoring opportunities.

It was reported

that

27 had participated in a formal program, as a mentor and 11 had participated in

a formal program, as a mentee.

In

total, 35 respondents (76%) replied that they had achieved tenure either at

their previous institution, at their current institution, or both. At their

current institutions 33 of the respondents are currently at the rank of

Associate Librarian or Librarian. There were 11 respondents who skipped past

this question, which did not have a required response; it is unclear if the

respondent refused to answer this question, accidentally skipped answering, or

if they did not achieve tenure at their previous or current institution.

Early

successful efforts in conducting research were mainly conducted as solo

endeavors, noted by 25 respondents. Similarly, 22 responded that they currently

mainly conduct their research alone.

Research Network

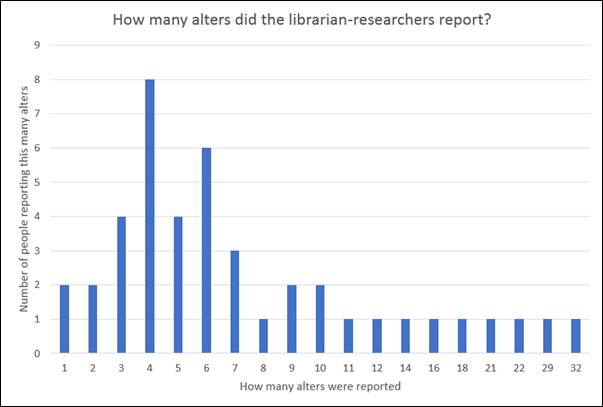

Of the

respondents, 43 provided complete network data. The number of people in each

research network ranged from 1 to 32, with the most frequently reported as 4

(with 8 respondents reporting this number). The average number of people in the

research networks is 8.09 (SD =

7.03). See Figure 1 for the range of network sizes reported by the respondents.

Of the 348 total people mentioned, the respondents reported having been in

contact over 3 or more times, for any reason over the past 30 days, with 170

(48%). The respondents had research interactions with 82 (34%) of the 348

mentioned.

Figure 1

Numbers of people in the research network.

On average, the respondents offered help to 1.75 other people, with

even support on average of 4.90. As shown in Table 2, “Professional colleague”

is the group with the largest relationship type reported, with 172 people in

the category. It is interesting to note that in the relationship type of “both

friend and colleague,” reciprocal support is the highest, with 124 people

fitting those two criteria.

Table 2

Category of Relationship by Type of Support

(n = 348)

|

|

Personal friend |

Professional colleague |

Both friend and colleague |

|||

|

Number

reported |

% |

Number reported |

% |

Number reported |

% |

|

|

I’m usually asking this person for advice or help |

10 |

43.48 |

47 |

27.33 |

16 |

10.46 |

|

I’m usually giving this person advice or help |

3 |

13.04 |

56 |

32.56 |

13 |

8.50 |

|

It’s pretty even; I ask for help but also give help in equal

amounts |

10 |

43.48 |

69 |

40.12 |

124 |

81.05 |

|

Total |

23 |

100 |

172 |

100 |

153 |

100 |

Of the

179 people (of 348 total) identified as working at the same institution, in the

same library, the majority of communications are done in person, with 158

reported as such. Of the 35 identified as working at the same institution but

not in the library, half of communications are done in person, followed by

email. Of the 134 who do not work at the same institution, 43% (57) of those

communications are conducted via email.

The

majority of the 348 people mentioned as part of the respondents’ research

networks are not involved in any mentor relationship, with 219 being identified

as having “no mentor relationship between us.” Of the 348, 67 are reported as

being the mentor in the relationship, and 62 as being the mentee.

Of the

2,273 possible relationships between the persons named, the average density is

54% (SD = 0.49). Only 361 (or about 16%) do research together.

Beliefs about and the Practice of the Research Process

All 46

respondents answered each research process question (listed in Appendix E).

Among the four lowest scoring questions were three questions designed to

measure peer support and one related to extrinsic motivation. Two of the three

peer support questions ask about participation in a writing group and a journal

club, both support activities that are relatively recent activities and focused

on the needs of novice researchers. The lowest scoring question, with only

seven yes responses, states “I do

research only because it is a requirement of my job.” The 12 highest scoring

questions, with scores at or above 40, were designed to measure personal

commitment to research, institutional support, extrinsic motivations, and

personality traits. Of the 46 respondents 45 answered yes to: “I can achieve my research goals”; and “Publishing gives me

a personal sense of satisfaction”.

Research

Productivity

As

shown in Table 3, presentations are the most recorded research output,

accounting for 49.91% of total research output (802 presentations). The least

recorded research output, accounting for just 0.50%, are edited books. The one

output type which all participants had used is peer-reviewed articles, with one

as the minimum recorded; all other output types have zero recorded as the

minimum. The research output scores for each participant were calculated

according to the weights noted in Table 1 and ranged from 32.5 to 307.

Correlations between Research Output and Professional Training,

Research Environment

There were no significant correlations between research output and

professional training or research environment. Completing a thesis for an

additional master’s degree (other than the LIS) was also not significantly

correlated with research output (U =

78.5, p = .838). Belief that one’s

LIS degree had prepared one to read and understand research-based literature

and research output was also found to be not statistically significant, as well

as belief that one’s LIS degree had prepared one to conduct original research (U = 244.5, p = .954 and U = 126.5, p = .530, respectively). The authors

divided into one group those respondents who reported participating in four or more

educational activities about research methods and into another group those who

reported three or fewer, of seven possible activities listed in the survey, but

found no statistically significant difference between the groups, related to

research output (U = 236.5, p = .727). The authors found no

statistical significance between the number of research support options

provided by the institution or library, and research output (rs(46)

= .181, p = .228). There is no

statistically significant difference in the distributions of those who are

currently tenured and research output

(U = 207.5, p = .864).

Table 3

Participant Research Output, 2008-2018

|

Output type |

Min |

Max |

Mean |

Median |

SD |

Total number reported |

% of output reported |

|

Poster |

0 |

68 |

3.7 |

1 |

10.3 |

169 |

10.52% |

|

Presentation |

0 |

92 |

17.4 |

11 |

21.5 |

802 |

49.91% |

|

Conference

proceeding |

0 |

7 |

1.2 |

0 |

1.9 |

55 |

3.42% |

|

Non-peer-reviewed

article |

0 |

14 |

1.6 |

1 |

2.5 |

74 |

4.60% |

|

Book

chapter |

0 |

12 |

1.9 |

1 |

2.4 |

86 |

5.35% |

|

Edited

book |

0 |

2 |

0.2 |

0 |

0.4 |

8 |

0.50% |

|

Peer-reviewed

article |

1 |

27 |

8.6 |

8 |

5.4 |

397 |

24.70% |

|

Authored

book |

0 |

3 |

0.35 |

0 |

0.7 |

16 |

1.00% |

Research

Output, Related to the Research Network

Ego-centric

network size was not significantly correlated with research output (rs(46)

= -.061, p = .687). Also, having any

type of mentor relationship with an alter (as formal mentor, as informal

mentor, as formal mentee, as informal mentee) was not significantly correlated

with research output (U = 216.5, p = .372; U = 193.5, p = .608; U = 147, p = .251; U = 222.5, p = .686). Being above average in giving

help or above average in giving/taking an equal amount of help from those in

the research network was also not significantly correlated with research output

(rs(11) = .318, p = .341

and rs(15) = -.190, p =

.498, respectively). There was no significant correlation between the number of

alters in the research network who either worked in the library or at the

university and research output (rs(43) = -.098, p = .530). The authors did find that the density of egocentric

networks defined by ties between alters who both knew each other and did

research together was significantly correlated with research output (rs(41)

= .398, p = .010). The denser the

research collaboration network, the higher the research output. Figure 2 shows

an example of a network of a low research output respondent that also has a

low-density network and a network of a high research output respondent, with a

high-density network. It is interesting to note that in the low research output

network, most of the alters are categorized as colleagues only, with a few

friends/colleagues but in the high research output network all of the alters

are categorized as both friends/colleagues.

Figure 2

Research output and research tie density.

Research

Output, Related to Statements about the Research Process

The

authors tested for associations between each of the 28 statements and research

output and found 1 significant association. The distribution of the statement,

“I have space where I am able to work effectively on my research” is similar to

the distribution of research output (U

= 10, p = .009).

The

authors replicated the analysis completed by Hoffmann et al. (2017), using the

number of peer-reviewed articles as the outcome variable, with no resulting

statistical significance.

Responses to Open-ended Questions

The responses to

the open-ended questions revealed important factors in the librarians’ process

in becoming accomplished researchers. Respondents noted that the research environment

can be a major contributor to research productivity, or it can be a hindrance.

A positive environment has many components, including institutional supports,

collaboration, and community. The environment that many respondents found most

conducive to developing as a researcher includes high expectations; a variety

of supports for research; and extrinsic rewards, such as salary increases,

tenure, promotion, and opportunities for advancement. This is an illustrative

comment: “My library is very supportive of research and scholarship, and

librarians are expected to publish and work on scholarly projects.” Many

librarians noted that being on the tenure-track provided an extrinsic

motivation to develop research skills and become a productive researcher. One

librarian wrote: “There is both pressure and support in tenure track positions

for conducting research.” Another theme was that often librarians conduct

research in order to fulfill the requirements of tenure but develop a personal

commitment to research and intrinsic motivation. This is a representative

comment: “The tenure track and the focus on writing was a big element that got

me started. Once I became comfortable, I realized how much I enjoyed

writing.”

Another

important factor is supportive colleagues and a community of researchers. This

is an illustrative comment: “Librarians have created networks of support such

as writing sessions and research forums, in which we share our projects with

our colleagues and possibly find opportunities to cooperate.” Some of the

comments reveal personality traits that contribute to research success. This is

representative: “I believe in working for shared good, which is truly

collaborative. I base my work on mutual aid and tend and befriend (not

competitive, pushing ourselves to be our best together, inclusivity and

diversity that grows and improves from our differences), and my collaborators

work in the same manner. This makes collaborative work more productive, better,

and more joyous.”

Discussion

The

most unique finding of this work relates to the research network. The authors

found that a high number of persons in the networks who both know each other

and do research together is significantly related to research output. The

denser the research network is in terms of research collaborations, the higher

the research output. Another finding of this work is that a productive grouping

of network members is those who are both friends and colleagues and also

give/take research help in equal amounts. These findings align well with the

responses to the open-ended question about the people in the current research

network that may have contributed to the productivity of the respondent, which

are mainly on the theme of collaboration.

As

might be expected, there was little variation in responses to yes and no statements designed to differentiate successful

librarian-researchers from other librarians. The librarians in the present

study were chosen because they are all accomplished researchers. Of the 28

statements about the research process, the strongest group response was to the

statement, “I can achieve my research goals”; 45 of 46 respondents agreed in

the affirmative that this statement does generally apply to them. Of the

respondents, 44 have “participated in activities that support LIS research,”

and 43 “have space where I am able to work effectively on my research.”

The

authors’ statistical tests of associations between research output and all

other variables from the survey overwhelmingly did not show significant findings.

In the area of professional training and research environment, there were no

significant correlations between those variables and research output. Fiawotoafor et al., as did the authors, found no positive

correlation between number of years in the profession and research output

(2018). In the area of research networks, the one meaningful significant

finding is that those who have networks with high density of research

collaborators was significantly related to research output. In the area of the

statements about the research process there was one significant association,

with those who said that they had space where they can work effectively on

their research tended to have higher research output. The authors wish to be

clear that this finding does not imply a causality; it may be that having space

helps productivity or that productive researchers make sure to have space to

work productively.

The

open-ended questions revealed both commonalities and differences among the

respondents. They offer important insights into the individual motivations of

librarian-researchers. In addition to the many positive factors in their lives

and professional environments, the open-ended questions also provided

respondents with an opportunity to mention negative factors in research

productivity, including the loss of a supportive supervisor or administrator,

the demands of a new administrative position, family pressures, and anxiety

over the need to publish and achieve tenure. The impact of assuming an

administrative position is especially interesting; respondents noted that this

changed their research or hampered their ability to conduct and disseminate

research.

Limitations of This Study and Future Research

This study is the first to examine the research experiences and

beliefs of accomplished librarian-researchers. One limitation of the study is

the difficulty in defining the population. Although all respondents are among

the most productive librarian-researchers in the U.S., many equally productive

researchers may have been missed by the methodology used to identify them. The

respondents vary in the volume of their research output and the types of their

research output. Hoffmann et al. (2017) noted that librarians often disseminate

the results of their research via conference presentation rather than

publication. The authors found this to be true as well and considered that

non-research presentations might skew the research totals. In order to reduce

this effect, the authors counted only presentations that are scholarly in

nature. The point system also strongly favors publication over presentation. In

a future study, the authors would like to explore the phenomenon of librarians

presenting about their research rather than publishing their findings. Another

interesting finding is that while most of the respondents have a positive

attitude toward research and feel confident in their research abilities, some

expressed a high level of anxiety regarding research and do not enjoy research.

The authors plan to explore these factors in follow-up interviews with the

respondents. What is the source of this anxiety and lack of confidence?

The authors do not report in this study on the hierarchical academic

rank of the people the librarian-researchers identify in their networks (as

described in Fu, Velema, & Hwang, 2018), though this may be a fruitful

topic of conversation in follow-up interviews. The authors could discover if

the choices the librarian-researchers made about the people in the development

of their research networks over the course of their career were decided based

on “reaching up” in the hierarchy, to gain a research-related benefit (Fu et

al., 2018, p. 266). This line of inquiry would expand on a narrow area of focus

in this research, that of mentor relationships, and whether the respondents act

as mentees (those in a lower rank gain an advantage from a mentor in a higher rank),

mentors, or have no mentor relationship with those identified in their research

networks (Abramo, D’Angelo & Murgia, 2017; Hollingsworth & Fassinger,

2002).

For this work the authors do not focus on collaborations leading to

co-authorship, though that is well addressed in the literature (see Lee &

Bozeman, 2005, and Xia, Chen, Wang, Li, & Yang, 2014) and may be an area

the authors identify as a possible future area of inquiry with this data set.

Abramo et al. (2019) describe in their work the advantage of scientific

collaboration may have, especially related to attracting different resources

and perspectives which result in a wider audience for the research. The authors

did notice during their review of the CVs that some of those in the population

were co-authors, so in future work the group may examine the co-authorship

network to look for associations between centrality and research output (as in

Abbasi, Altmann & Hossain, 2011, and Abbasi, Jalili, & Sadeghi-Niaraki,

2018).

Finally, the authors did not address the concept of gender and

research productivity. Research is being conducted in this area (see Mayer

& Rathmann, 2018) and is a topic of concern, given that the field of

librarianship is dominated by women. Hoffmann et al. (2017) found that gender did

not have a significant effect on research productivity and so for this work the

authors decided not to pursue that as a variable. However, for

librarian-researchers at the highest levels of accomplishment, there may be

gender differences. This may be an interesting area of inquiry for follow-up in

interviews with respondents.

Summary

This

work explores the factors that may contribute to a librarian becoming an

accomplished researcher. An understanding of these factors can provide evidence

based guidance to those at the beginning of their research careers in designing

their own trajectories. It may also aid library administrators in creating a

supportive environment for researchers.

The

population studied is the group of librarians identified as accomplished

researchers. They were identified through 2 means: employed at Association of

Research Libraries institutions who published more than 5 items indexed in the

Social Science Citation Index in the last 10 years and the top 50 most

published librarian-researchers for 2007-2012 (Walters & Wilder, 2015).

This population was recruited into the study that included both a survey and CV

component.

Analyses

of the resulting survey data and CV data show that this population has

professional training backgrounds and current environments that vary widely and

are not statistically associated with research output. Those with a high number

of persons in their networks who both know each other and do research together

is significantly related to research output, a unique finding for the

profession of library science. A large group of those identified in the

research networks are “both friend and colleague” and offer each other

reciprocal support. Those who agree with the statement, “I have space where I

am able to work effectively on my research” is also associated with research

output.

The

statistical data do not tell the entire story, however. In open-ended

questions, the respondents cited numerous factors over their careers that led

to their research success. These factors span the three categories identified

and studied by Hoffmann et al. (2014, 2017). The results of this study support

their finding that becoming a productive researcher is the product of

individual attributes, peers and community, and institutional structures. From

these categories, the three most frequently-mentioned factors from the

open-ended questions were developing a personal commitment to research,

collaboration, and positive organizational climate. Furthermore, the open-ended

questions allowed the respondents to elaborate on positive and negative

influences in their educational background; previous work; and professional and

personal environments.

Acknowledgments

This project was made possible in part by

the Institute of Museum and Library Services grant RE-40-16-0120-16.

The authors thank SCELC (https://scelc.org/) for providing a Research Incentive Grant to

supply some of the monetary incentives for this research.

References

Abbasi, A., Altmann, J., & Hossain, L. (2011).

Identifying the effects of co-authorship networks on the performance of

scholars: A correlation and regression analysis of performance measures and

social network analysis measures. Journal of Informetrics, 5(4), 594-607. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joi.2011.05.007

Abbasi, A., Jalili, M., & Sadeghi-Niaraki, A.

(2018). Influence of network-based structural and power diversity on research

performance. Scientometrics,

117, 579-590. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-018-2879-3

Abramo, G., D’Angelo, C. A., & Di Costa, F.

(2019). The collaboration behavior of top scientists. Scientometrics, 118, 215-232.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-018-2970-9

Abramo, G., D’Angelo, A. C., & Murgia, G. (2017).

The relationship among productivity, research collaboration, and

their determinants. Journal of Informetrics, 11(4), 1016-1030. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joi.2017.09.007

Association of Research Libraries. (2019). List of ARL Members.

Retrieved from https://www.arl.org/membership/list-of-arl-members

Berg, S. A., Jacobs, H.L.M., &

Cornwall, D. (2013). Academic librarians and research: A study of Canadian

library administrator perspectives. College

and Research Libraries 74(6), 560-572. https://doi.org/10.5860/crl12-366

Borgatti, S. P., Everett, M. G., & Johnson, J. C. (2013). Analyzing

social networks. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications Limited.

Chang, Y-W. (2016). Characteristics of

articles co-authored by researchers and practitioners in library and

information science journals. The Journal

of Academic Librarianship 42(5), 535-541. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2016.06.021

Clarivate. (2018). Web of Science.

Retrieved from http://webofknowledge.com/wos

Crossley, N., Bellotti, E., Edwards, G.,

Everett, M. G., Koskinen, J., & Tranmer, M. (2015). Social network

analysis for ego-nets. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications Limited.

Csárdi, G. (2019). Package ‘igraph.’ Retrieved from https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/igraph/igraph.pdf

EgoWeb 2.0 [Computer software]. (2015).

Retrieved from https://github.com/qualintitative/egoweb

Fennewald, J. (2008). Research

productivity among librarians: Factors leading to publications at Penn

State. College & Research Libraries, 69(2), 104-116. https://doi.org/10.5860/crl.69.2.104

Fiawotoafor, T., Dadzie, P. S., &

Adams, M. (2019, January). Publication output of professional librarians in public

university libraries in Ghana. Library Philosophy and Practice

(e-journal) 1-40. Retrieved from https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/libphilprac/2303/

Fu, Y.-c.,

Velema, T. A., & Hwang, J.-S. (2018). Upward

contacts in everyday life: Benefits of reaching hierarchical relations in

ego-centered networks. Social Networks, 54, 266-278. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socnet.2018.03.002

Galbraith, Q., Smart, E., Smith, S. D.,

& Reed, M. (2014). Who publishes in top-tier library science journals? An

analysis by faculty status and tenure. College & Research

Libraries, 75(5), 724-735. https://doi.org/10.5860/crl.75.5.724

Hoffmann, K., Berg, S. A., &

Koufogiannakis, D. (2014). Examining success: Identifying factors that

contribute to research productivity across librarianship and other

disciplines. Library and Information Research, 38(119), 13-28. https://doi.org/10.29173/lirg639

Hoffmann, K., Berg, S., &

Koufogiannakis, D. (2017). Understanding factors that encourage research

productivity for academic librarians. Evidence Based Library and Information

Practice, 12(4). https://doi.org/10.18438/B8G66F

Hollingsworth, M. A.,

& Fassinger, R. E. (2002). The role of faculty mentors in the research

training of counseling psychology doctoral students. Journal of

Counseling Psychology, 49(3), 324-330. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.49.3.324

Hollister, C. V. (2016). An exploratory

study on post-tenure research productivity among academic librarians. The

Journal of Academic Librarianship, 42(4), 368-381. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2016.04.021

Kennedy, M. R., & Brancolini, K. R.

(2018). Academic librarian research: An update to a survey of attitudes,

involvement, and perceived capabilities. College & Research

Libraries, 79(6), 822. https://doi.org/10.5860/crl.79.6.822

Kennedy, M. R., Kennedy, D. P., &

Brancolini, K. R. (2017). The evolution of the personal networks of novice

librarian researchers. portal: Libraries

and the Academy, 17(1), 71-89. https://doi.org/10.1353/pla.2017.0005

Krackhardt, D. (1987). Cognitive social structures. Social Networks,

9(2), 109-134. https://doi.org/10.1016/0378-8733(87)90009-8

Lee, S., & Bozeman, B. (2005). The

impact of research collaboration on scientific productivity. Social

Studies of Science, 35(5), 673-702. https://doi.org/10.1177/0306312705052359

Luo, L. (2011). Fusing research into

practice: The role of research methods education. Library &

Information Science Research, 33(3), 191-201. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lisr.2010.12.001

Luo, L., & McKinney, M. (2015). JAL in the past decade: A comprehensive

analysis of academic library research. The

Journal of Academic Librarianship 41(2): 123-129. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2015.01.003

Mayer, S. J., & Rathmann, J. M. K.

(2018). How does research productivity relate to gender? Analyzing gender

differences for multiple publication dimensions. Scientometrics, 117,

1663-1693. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-018-2933-1

McCarty, C. (2002). Structure in

personal networks. Journal of Social Structure, 3(1). Retrieved

from https://www.cmu.edu/joss/content/articles/volume3/McCarty.html

McCarty, C., Lubbers, M., Vacca, R., & Molina,

J. L. (2019). Conducting personal network

research: A practical guide. Guilford Press.

Meadows, K. N., Berg, S. A., Hoffmann,

K., Gardiner, M. M., & Torabi, N. (2013). A needs-driven and responsive

approach to supporting the research endeavours of academic librarians. Partnership: the

Canadian Journal of Library and Information Practice and Research 8(2), 1-32.

https://doi.org/10.21083/partnership.v8i2.2776

Perkins, G. H., & Slowik, A. J. W.

(2013). The value of research in academic libraries. College &

Research Libraries, 74(2), 143-158. https://doi.org/10.5860/crl-308

Sassen, C., & Wahl, D. (2014).

Fostering research and publication in academic libraries. College & Research Libraries 75(4), 458-49. https://doi.org/10.5860/crl.75.4.458

Smigielski, E. M., Laning, M. A., &

Daniels, C. M. (2014). Funding, time, and mentoring: A study of

research and publication support practices of ARL member libraries. Journal of Library Administration, 54(4), 261-276. https://doi.org/10.1080/01930826.2014.924309

Vilz, A. J., & Poremski, M. D.

(2015). Perceptions of support systems for tenure-track librarians. College

& Undergraduate Libraries, 22(2), 149-166. https://doi.org/10.1080/10691316.2014.924845

Walters, W. H., & Wilder, E. I.

(2015). Worldwide contributors to the literature of library and information

science: top authors, 2007-2012. Scientometrics, 103, 301-327. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-014-1519-9

Wasserman, S., & Faust, K.

(1994). Social network analysis: Methods and applications. New

York: Cambridge University Press.

Watson-Boone, R. (2000). Academic

librarians as practitioner-researchers. The Journal of Academic

Librarianship, 26(2), 85-93. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0099-1333(99)00144-5

Xia, F., Chen, Z., Wang, W., Li, J.,

& Yang, L. T. (2014). MVCWalker: Random walk-based most valuable

collaborators recommendation exploiting academic factors. IEEE

Transactions on Emerging Topics Computing, 2(3), 364-375. https://doi.org/10.1109/TETC.2014.2356505

Appendix A

Recruitment

email

Email

subject: Personal invitation, survey for accomplished librarian-researchers

Email

body:

Greetings!

We

invite you to participate in a study of accomplished librarian-researchers. We

selected you for this study based on your high number of publications in recent

years. As part of a small group of productive librarian-researchers, we hope

you will agree to participate in the study. The purpose of the study is to

understand the factors that contributed to your productivity.

For

your participation, we are pleased to offer you a $100.00 gift card (via

https://www.giftcards.com/virtual-gift-cards). Your participation includes two

actions:

1. Complete a web-based survey. In the

survey, we will ask you to click through a series of questions with options for

response. The survey can take up to 30 minutes to complete.

2. Send your current CV to Marie Kennedy at

marie.kennedy@lmu.edu, so that we may examine the last ten years of your

scholarly productivity and professional experience.

We

plan to publish and present the results of this study. At the time of

publishing and presenting, the data will be anonymized. There are no expected

risks for you in participating in this research.

To

initiate your participation, please complete the survey at [personalized survey

URL]. Use the email address [participant’s email address] at the prompt in the

survey. Please plan to complete the survey by July 1, 2018.

Your

voice is an important one in this research. Thank you for your consideration.

Kind

regards,

Marie

R. Kennedy, Loyola Marymount University

Kristine

R. Brancolini, Loyola Marymount University

David

P. Kennedy, RAND Corporation

Appendix B

Survey

Page

1: Accomplished Librarian-Researchers -- Informed Consent

Introduction

to the Study

We

invite you to participate in a study of accomplished librarian-researchers.

You

have been selected for this study based on your high number of publications in

peer-reviewed journals in recent years. As part of a small group of productive

librarian-researchers, we hope you will agree to participate in the study.

Purpose

The

purpose of this study is to understand the factors that contributed to the

productivity of accomplished librarian-researchers.

We

hope to publish and present the results of this study. At the time of

publishing and presenting the data will be anonymized.

What

Will Happen During the Study

We

will ask you to take two actions:

1.

Complete this web-based survey. In the survey we will ask you to click through

a series of questions with options for response. The survey is likely to take

up to 30 minutes to complete.

2.

Send your current CV to Marie Kennedy at marie.kennedy@lmu.edu, so that we may

examine the last ten years of your scholarly productivity and professional

experience.

Your

Privacy is Important

We

will make every effort to protect your privacy.

No

sensitive information will be gathered as part of this survey.

Any

information you provide will remain confidential. Only the co-investigators

will view the results of the survey in their raw form.

Your

Rights

Your

participation in this study is completely voluntary and no risks are

anticipated for you as a result of participating.

If

you decide to be in the study, you will have the right to stop participating at

any time.

Incentive

When

the co-investigator has confirmed that your CV has been received and the survey

completed you will be sent a $100.00 gift card from any eGift card brand listed

at https://www.giftcards.com/virtual-gift-cards.

Institutional

Review Board Approval

This

study has been reviewed by the Office of Research and Sponsored Projects at

Loyola Marymount University. If you have any questions about your rights as a

research participant in this study, please contact the David A. Moffet, Ph.D.,

Chair, Institutional Review Board, Loyola Marymount University, One LMU Drive,

Suite 47000, Los Angeles, CA 90045 at (310) 338-4400 or at david.moffet@lmu.edu.

If

you agree with all of the above statements, provide your electronic signature

by clicking on "Next" below.

Page

2: Introduction to the survey

There are three sections to this survey. It begins with a series of questions

about your research training and work environment, continues with a section

about your research network, and finishes with a series of statements about the

research process.

Question

1. Please select the response that best describes your graduate-level

educational background.

I

have an LIS Master’s degree

I have an LIS and another Master’s degree

I have a non-LIS Master’s degree

I have a doctoral degree

Question

2. In what year did you complete your LIS degree? Enter the four-digit year.

Text

entry for response

(Question

2 appears if Question 1 response is I

have an LIS Master’s degree or I have

an LIS and another Master’s degree)

Question

3. Did you write a thesis in completing your LIS degree?

Yes

No

I don’t remember

(Question

3 appears if Question 1 response is I

have an LIS Master’s degree or I have

an LIS and another Master’s degree)

Question

4. Did you write a thesis in completing another master's degree?

Yes

No

I don’t remember

(Question

4 appears if Question 1 response is I

have an LIS and another Master’s degree or I have a non-LIS Master’s degree)

Question

5. Do you believe that your LIS master's degree adequately prepared you to read

and understand research-based literature?

Yes

No

(Question

5 appears if Question 1 response is I

have an LIS and another Master’s degree or I have an LIS and another Master’s degree)

Question

6. Do you believe that your LIS master's degree adequately prepared you to

conduct original research?

Yes

No

(Question

6 appears if Question 1 response is I

have an LIS and another Master’s degree or I have an LIS and another Master’s degree)

Question

7. In which of the following educational activities about research methods have

you ever participated? Check all that apply.

Formal

master's degree LIS course(s) (e.g., research methods, statistics)

Formal master's degree non-LIS course(s) (e.g., courses in other departments)

Formal doctoral degree LIS course(s) (e.g., research methods, statistics)

Formal doctoral degree non-LIS course(s) (e.g., courses in other departments)

Continuing education program(s): Workshops, conferences, or other continuing

education activities outside the library/your institution

Staff development program(s) provided by your library or university

Self-education activities (e.g., professional reading, online tutorial)

None of these

Question

8. Did you take advantage of any of the following research support options

provided by your institution or library when you were early in your research

career? Check all that apply.

Release

time during the work week

Short-term pre-tenure research leave

Sabbaticals for librarians

Travel funds (full reimbursement)

Travel funds (partial reimbursement)

Research grants

Formal mentorship (experienced librarian researcher partners with novice

researcher)

Informal mentorship (journal club discussions or article/proposal feedback

sessions)

Research design or statistical consultant

Workshops or other forms of continuing education

No research support was available to me

Question

9.1. Which of the following research support options does your current

institution or library provide for librarians, and which have you taken

advantage of? Release time during the

work week

It

is offered and I HAVE taken advantage of it

It is offered but I HAVE NOT taken advantage of it

It is not offered

Question

9.2. Which of the following research support options does your current

institution or library provide for librarians, and which have you taken

advantage of? Short-term pre-tenure

research leave

It

is offered and I HAVE taken advantage of it

It is offered but I HAVE NOT taken advantage of it

It is not offered

Question

9.3. Which of the following research support options does your current

institution or library provide for librarians, and which have you taken

advantage of? Sabbaticals for librarians

It

is offered and I HAVE taken advantage of it

It is offered but I HAVE NOT taken advantage of it

It is not offered

Question

9.4. Which of the following research support options does your current

institution or library provide for librarians, and which have you taken

advantage of? Travel funds (full

reimbursement)

It

is offered and I HAVE taken advantage of it

It is offered but I HAVE NOT taken advantage of it

It is not offered

Question

9.5. Which of the following research support options does your current

institution or library provide for librarians, and which have you taken

advantage of? Travel funds (partial

reimbursement)

It

is offered and I HAVE taken advantage of it

It is offered but I HAVE NOT taken advantage of it

It is not offered

Question

9.6. Which of the following research support options does your current

institution or library provide for librarians, and which have you taken

advantage of? Research grants

It

is offered and I HAVE taken advantage of it

It is offered but I HAVE NOT taken advantage of it

It is not offered

Question

9.7. Which of the following research support options does your current

institution or library provide for librarians, and which have you taken

advantage of? Formal mentorship

(experienced librarian-researcher with an agreement to advise a less

experienced librarian-researcher – one-on-one)

It

is offered and I HAVE taken advantage of it

It is offered but I HAVE NOT taken advantage of it

It is not offered

Question

9.8. Which of the following research support options does your current

institution or library provide for librarians, and which have you taken

advantage of? Informal mentorship (more

casual one-on-one consultation about research or peer mentoring, such as

journal clubs discussions or article/proposal feedback sessions)

It

is offered and I HAVE taken advantage of it

It is offered but I HAVE NOT taken advantage of it

It is not offered

Question

9.9. Which of the following research support options does your current

institution or library provide for librarians, and which have you taken

advantage of? Research design or

statistical consultant

It

is offered and I HAVE taken advantage of it

It is offered but I HAVE NOT taken advantage of it

It is not offered

Question

9.10. Which of the following research support options does your current

institution or library provide for librarians, and which have you taken

advantage of? Workshops or other forms of

continuing education

It

is offered and I HAVE taken advantage of it

It is offered but I HAVE NOT taken advantage of it

It is not offered

Question

10.1. Have you ever participated in any of the following types of mentorship

program? Formal mentorship (experienced

librarian-researcher with an agreement to advise a less experienced

librarian-researcher – one-on-one) in which you are the mentor

Yes

No

Question

10.2. Have you ever participated in any of the following types of mentorship

program? Formal mentorship (experienced

librarian-researcher with an agreement to advise a less experienced

librarian-researcher – one-on-one) in which you are the mentee

Yes

No

Question

10.3. Have you ever participated in any of the following types of mentorship

program? Informal mentorship (more casual

one-on-one consultation about research or peer mentoring, such as journal clubs

discussions or article/proposal feedback sessions) in which you are the mentor

Yes

No

Question

10.4. Have you ever participated in any of the following types of mentorship

program? Informal mentorship (more casual

one-on-one consultation about research or peer mentoring, such as journal clubs

discussions or article/proposal feedback sessions) in which you are the mentee

Yes

No

Question

11. Have you attained tenure?

At

a previous institution

At my current institution

Question

12. What is the highest rank you attained at a previous institution?

Assistant

librarian/professor

Associate librarian/professor

Librarian/Professor

n/a Librarians do not have academic rank

(Question

12 appears if Question 11 response is At

a previous institution)

Question

13. What is the highest rank you attained at your current institution?

Assistant

librarian/professor

Associate librarian/professor

Librarian/Professor

n/a Librarians do not have academic rank

(Question

13 appears if Question 11 response is At my current

institution)

Question

14. In what year did you complete your highest academic rank? Enter the

four-digit year.

Text

entry response

(Question

14 appears if Question 13 response is Assistant

librarian/professor, Associate

librarian/professor, or Librarian/Professor)

Question

15. Think back to your earliest successful efforts in conducting research. How

did you mainly conduct it?

Mainly

solo

Mainly with a partner who was more experienced than I was

Mainly with a partner who was less experienced than I was

Mainly with a partner who was equally experienced as I was

Mainly on a team of novice researchers

Mainly on a team with both novice and more experienced researchers

Question

16. Describe the type of research you are currently conducting. What methods

are you using? What research questions are you exploring?

Text

entry response

Question

17. How do you mainly conduct your current research? Check all that apply.

Mainly

solo