Research Article

Teaming up to Teach Teamwork in an LIS Master’s Degree

Program

Lauren H. Mandel, PhD

Associate Professor

Graduate School of Library and

Information Studies, University of Rhode Island

Kingston, Rhode Island, United

States of America

Email: lauren_mandel@uri.edu

Mary H. Moen, PhD

Assistant Professor

Graduate School of Library and

Information Studies, University of Rhode Island

Kingston, Rhode Island, United

States of America

Email: mary_moen@uri.edu

Valerie Karno,

PhD, JD

Associate Professor and

Director

Graduate School of Library and

Information Studies, University of Rhode Island

Kingston, Rhode Island, United

States of America

Email: vkarno@uri.edu

Received: 27 Nov. 2019 Accepted: 10 Apr. 2020

![]() 2020 Mandel, Moen, and Karno. This is an Open Access article

distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

2020 Mandel, Moen, and Karno. This is an Open Access article

distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

DOI: 10.18438/eblip29684

Abstract

Objective – Collaboration and working in

teams are key aspects of all types of librarianship, but library and

information studies (LIS) students often perceive teamwork and group work

negatively. LIS schools have a responsibility to prepare graduates with the

skills and experiences to be successful working in teams in the field. Through

a grant from the university office of assessment, the assessment committee at

the University of Rhode Island Graduate School of Library and Information

Studies explored their department’s programmatic approach to teaching teamwork

in the MLIS curriculum.

Methods – This research followed a multi-method design

including content analysis of syllabi, secondary analysis of student evaluation

of teaching (SET) data, and interviews with alumni. Syllabi were analyzed for

all semesters from fall 2010 to spring 2016 (n = 210), with 81 syllabi

further analyzed for details about their team assignments. Some data was

missing from the dataset of SETs purchased from the vendor, resulting in a

dataset of 39 courses with SET data available. Interviews were conducted with a

convenience sample of alumni about their experiences with teamwork in the LIS

program and their view of how well the LIS curriculum prepared them for

teamwork in their careers (n = 22).

Results – Findings indicate that, although alumni

remembered teamwork happening too often, it was required in just over one-third

of courses in the sample period (fall 2010 to spring 2016), and teamwork

accounted for about one-fifth of assignments in each of these courses. Alumni

reported mostly positive experiences with teamwork, reflecting that teamwork

assignments are necessary for the MLIS program because teamwork is a critical

skill for librarianship. Three themes emerged from the findings: alumni perceived teamwork to be important for

librarians and therefore for the MLIS program, despite this perception there is

also a perception that the program has teamwork in too many courses, and

questions remain about whether faculty perceive teaching teamwork as important

and how to teach teamwork skills in the MLIS curriculum.

Conclusions – Librarians need to be able to

collaborate internally and externally, but assigning team projects does not

guarantee students will develop the teamwork skills they need. An LIS program

should be proactive in teaching skills in scheduling, time management, personal

accountability, and peer evaluation to prepare students to be effective

collaborators in their careers.

Introduction

While not all

library and information studies (LIS) courses emphasize teamwork, it is a

crucial skill for students to be successful in the field (Evans & Alire, 2013; Henricks & Henricks-Lepp,

2014). Yet, how is teamwork taught and evaluated as a learning objective in a

graduate library school program? The assessment committee at the University of

Rhode Island Graduate School of Library and Information Studies (URI GSLIS)

conducted a review of aggregated mean scores on the 12 learning objectives from

the IDEA student evaluation of teaching (SET) instrument, which includes

learning how to work with others on a team. The IDEA Student Ratings of

Instruction are a proprietary SET sold by Campus Labs; the instrument measures

student self-reported perceptions of their learning on 12 IDEA learning

objectives. The university administers the IDEA survey each semester, asking

students to self-report their perceived learning for each of the 12 IDEA

learning objectives, regardless of whether those objectives are relevant to the

course. The assessment committee discovered that the mean score on objective 5,

“acquiring skills in working with others as a member of a team,” was the lowest

of all 12 objectives across all courses for which an IDEA survey was

administered, 2010 to 2016. While this is a self-assessment of learning,

instructors at URI GSLIS had informally discussed their observation of

students’ negativity concerning group work, and the review brought to light the

omission of teamwork or collaboration from the department learning outcomes.

The committee determined that improving teamwork skills for LIS students should

be a department priority.

The terms

collaboration, group work, and teamwork are often used interchangeably. The

term used in the IDEA objective is “team,” which was the inspiration behind the

title of this project. For purposes of this paper, teamwork refers to any

assignment in a course that requires two or more students to work together to

produce an output, whether this was labeled as group work, teamwork, partner

work, or collaboration. There might have been one grade assigned to the group,

or students might have been assigned grades individually.

Teamwork

assignments in LIS education allow students to assess and build team skills for

future use in the workplace (Rafferty, 2013). Working collaboratively in

libraries is increasingly necessary as problems become more complex and

resources become scarcer (Calvert, 2018; Laddusaw

& Wulhelm, 2018; Marcum, 2014). Collaborative

projects help library staff develop relationship building skills that can be

rewarding professionally. Collaborating within a library can increase

communications by breaking down silos, building trust among staff, leveraging

skill sets that complement each other, and allowing all involved to contribute

to projects and learn from colleagues (Bello et al., 2017; Calvert, 2018; Cole,

2017). Collaboration between libraries and other like-minded institutions can

improve the visibility of library services by increasing the use of library resources

and attendance at programs (Laddusaw & Wilhelm,

2018), raising public awareness of libraries (Marcum, 2014), and increasing

patron learning of information literacy skills (Laddusaw

& Wilhelm, 2018; Saines et al., 2019). Based on

the importance and benefits of collaboration for libraries, LIS schools have a

responsibility to prepare graduates with the skills and experiences to be

successful working collaboratively in the field.

Through a grant

from the URI office of assessment, the committee designed this study to explore

how teamwork was being taught across the curriculum and how alumni perceived

their experiences working in teams both in the MLIS program and their careers

in order to identify possible interventions to improve the department’s approach

to teaching teamwork and collaboration skills to MLIS students. Researchers

examined artifacts of teaching (course syllabi and scores on the IDEA teamwork

objective) and interviewed alumni about their experiences working in teams

during the MLIS program and in their careers. This study raised questions about

what the skills of teamwork are, how important teamwork is perceived to be for

LIS careers, and how teamwork skills can be taught effectively in an MLIS

program. Teamwork is a crucial skillset for LIS students to learn as it is a

requirement of most library jobs, but assigning team projects in courses is not

enough; students need to be actively taught teamwork skills to prepare them for

library jobs in which they will be asked to collaborate with colleagues inside

and outside their libraries.

Literature Review

Benefits of Teamwork

Teamwork is commonly utilized in higher education to

develop students’ collaboration and teamwork skills (O’Farrell & Bates,

2009; Rafferty, 2013; Snyder, 2009). Teamwork provides students the opportunity

for peer-to-peer interactions that support learning and building one’s network

(Roy & Williams, 2014). It leverages the strengths of team members and

provides opportunities to explore their abilities in a safe educational

setting. Collaborative learning is particularly beneficial in professional

Master’s degree programs because of the positive aspect of sharing life

experiences (Oliveira et al., 2011).

Student Perceptions of Teamwork

Students report

that they like teamwork because they can learn from peers and develop ongoing

relationships (Roy & Williams, 2014) and that teamwork was effective at

generating ideas (McKinney & Cook, 2018). Yet, they often see teamwork as a

negative aspect of courses that utilize it (Bernier & Stenstrom,

2016). Students do not enjoy having to depend on their peers who may have

different objectives and levels of commitment from them (Bernier & Stenstrom, 2016; Capdeferro &

Romero, 2012), they perceive there is an unfair system of reward and punishment

for teamwork and that students get away with doing little or nothing (Bernier

& Stenstrom, 2016; Capdeferro

& Romero, 2012; McKinney & Cook, 2018; Roy & Williams, 2014), they

identify problems with logistics (Bernier & Stenstrom,

2016; Capdeferro & Romero, 2012), and they fear

being stuck with all the work due to unbalanced workload among a team (Capdeferro & Romero, 2012; McKinney & Cook, 2018;

Roy & Williams, 2014). Issues in communicating (O’Farrell & Bates, 2009;

Shah & Leeder, 2016) and team dynamics (Calvert, 2018) are also commonly

cited challenges. Students also perceived that the lack of instructor input,

either guidance at beginning or assistance during a project, contributed

negatively to teamwork experiences (Capdeferro &

Romero, 2012). Student learning style also can affect how students perceive

teamwork; students who had negative perceptions of teamwork tend to prefer

working alone (Shah & Leeder, 2016).

Collaborative Learning in LIS Education

Since collaboration

is an “essential skill for students to acquire and practise,

as many real-world problems require us to work together” (Shah & Leeder,

2016, p. 609), then it is important for LIS schools to teach students how to

collaborate (Bernier & Stenstrom, 2016; Roy &

Williams, 2014; Shah & Leeder, 2016). Although students’ knowledge can

increase during the teamwork process, so might their stress level (Kim &

Lee, 2014). Communicating remains a challenge even when students used a variety

of electronic or digital resources during the teamwork process to share work

(O’Farrell & Bates, 2009). Structures such as a designated team leader,

scheduled meetings, and clear and regular communication positively affect the

team experience while perceived laziness of members does not (McKinney &

Cook, 2018). Interventions such as a video on how to work successfully in small

teams and explicit guidelines to enhance teamwork do not substantially lessen

the negative attitudes students held about teamwork (Bernier & Stenstrom, 2016). How to teach teamwork in a way that

students both learn from and enjoy it remains an area in need of further

investigation.

Methods

The URI GSLIS

assessment committee conducted an assessment research project, funded by a

university grant, to inform pedagogical improvement with regard to teamwork

across the entirety of the LIS curriculum, guided by three research questions:

- What is the average IDEA score on objective 5 in LIS

courses that require teamwork, and how does this compare to the overall

mean score across all LIS courses?

- How is teamwork taught in the LIS courses that

require it?

- How effective do students perceive the curriculum to

be in preparing them for teamwork in their careers?

This multi-method

research included content analysis of syllabi, secondary analysis of SET data,

and interviews with alumni.

Content Analysis

The department had

210 syllabi from Fall 2010 to Spring 2016. The sample included courses

delivered online, face to face, and in hybrid formats. A graduate assistant

(GA) working on the research project analyzed the syllabi to identify which

courses required team assignments. To ensure the most comprehensive dataset,

all assignments that required two or more students to work collaboratively to

produce a shared output were classified as teamwork for this study. The GA

tabulated the number of both required and optional team assignments, the total

number of assignments, and the percentage team assignments comprised of the

total grade. Syllabi were further coded for assignment type; inclusion of

assignment descriptions and rubrics that detailed teamwork expectations,

learning outcomes, or best practices/additional resources; and keywords used in

teamwork expectations or learning outcomes.

Secondary Analysis

In the 2016-17

academic year, the department, with the support of the university provost’s

office, purchased scores on the 12 IDEA learning objectives for all LIS courses

from fall 2010 to spring 2016 from Campus Labs (n=39). Preliminary analysis

focused on mean scores for the objectives across all courses (Mandel, 2017).

The secondary analysis dug deeper into the scores for individual courses on

objective 5, comparing courses identified in the content analysis as requiring

and not requiring teamwork. Some data was missing from the dataset due to

courses not having received an IDEA evaluation because they were taught by

adjuncts or faculty nearing retirement, had low enrollment, or were taught in

summer (URI had not been conducting IDEA evaluations on summer courses). Other

data was missing the course code on the Faculty Information Form, so the

courses could not be easily identified as LIS courses by Campus Labs.

Interviews

The project PI and

GA conducted telephone interviews with a convenience sample of alumni about

their experiences with teamwork in the LIS program and their view of how well

the LIS curriculum prepared them for teamwork in their careers. Alumni were

asked first about their experiences with teamwork in the MLIS program. They

were asked to describe one or two specific assignments they did as part of a

group, how the group coordinated the work and brainstormed, what they liked and

disliked about group work, whether an instructor ever did anything to make

their experience with group work easier or better, positive experiences working

in groups and what made these experiences positive, and challenging experiences

working in groups as well as strategies to mitigate or overcome those

challenges. Alumni were then asked about teamwork experiences in their careers.

They were asked to describe their experience with group work in their career,

how their group work experiences in the MLIS program influenced their ability to

work in groups on the job, what they like and dislike about group work on the

job, and what recommendations they had for MLIS instructors to prepare students

for professional group work.

Researchers used the department Constant Contact account

to recruit alumni who attended the program between fall 2010 and spring 2016 to

participate in the interviews. Alumni were not asked about demographic data

such as their gender, year of graduation, or the specific breakdown of the

formats of the courses they had taken, but during the time they attended the

program, 42.6% of program courses were offered in the hybrid format, 43.8% were

offered online, and 13.6% were offered face to face. One interviewee stated

during the first question that they were not really able to comment on the

topic so that interview was not utilized, leaving 22 completed interviews, at

which point the researchers were no longer learning anything new about alumni

experiences with teamwork in the program and had reached saturation. Both the PI

and GA took notes during the interviews and then analyzed their notes

thematically. Their analyses were collated to produce one set of emergent

themes.

Results

LIS Courses That Require Teamwork

Content analysis

revealed that 81 courses in the sample required teamwork (38.6%). Teamwork

assignments were most frequently required in courses on management, reference,

information science and technology, community relations, school library media,

information literacy instruction, and research methods. This represents a mix

of required and elective courses. Other courses that required teamwork once in

the sample period were collection management, academic libraries, instructional

design, children’s literature, youth services, social science reference, government

publications, archives and preservation, leadership, and internship. Courses in

instructional technology and social networking required teamwork twice during

the sample period. Optional teamwork assignments were found in courses on

collection management, information science and technology, special libraries,

and research methods.

The average number

of teamwork assignments used in courses that require teamwork is 2.3. (The

averages were 0.14 for courses with optional teamwork and 2.5 for all courses

with teamwork assignments). The average number of total assignments per course

is 13.4, meaning that required teamwork assignments comprised 19.0% of total

assignments, on average (1.8% for courses with optional teamwork and 20.8% for

all courses with teamwork assignments). Assignment types were categorized as

written, presentation, peer evaluation, discussion (either live in class or

asynchronous via online discussion board), interview, project, or role play.

The majority of teamwork assignments were written (n = 75; 87.2%), with

the next most popular assignments being presentations (n = 50; 58.1%)

and role play (n = 21; 24.4%); see Table 1.

Table 1

Types of Teamwork Assignments Used in

LIS Coursesa

|

Assignment Type |

Total Classes Using |

% Classes Using |

|

Written |

75 |

87.2 |

|

Presentation |

50 |

58.1 |

|

Role play |

21 |

24.4 |

|

Peer evaluation |

13 |

15.1 |

|

Discussion (live or online forums) |

10 |

11.6 |

|

Interview |

1 |

1.2 |

|

Project |

1 |

1.2 |

aSome

courses had multiple types of teamwork assignments, so percentages exceed 100%.

Forty-five syllabi

included teamwork expectations or learning outcomes (52.3%), 14 included

teamwork best practices or additional resources (16.3%), and 13 included peer

evaluation assignments (15.1%). The most frequently mentioned topic in teamwork

expectations or learning outcomes was collaboration (n = 60), followed

by respect (n = 35) and functionality (n = 32); see Table 2. Best

practices and additional resources included quotes, instructors’ advice on

being a good member of a team, and a chart comparing teams versus groups

referenced from a management textbook.

Table 2

Frequency of Topics in Teamwork

Expectations or Learning Outcomesa

|

Category |

n |

|

Collaboration

(including networks, partnerships, cooperation) |

60 |

|

Respect

(including appreciate, recognize) |

35 |

|

Functionality

(including evaluation, effectiveness, efficiency, practical) |

32 |

|

Communication

(including synthesizing ideas, openness) |

21 |

|

Equitable

workload |

17 |

|

Support

(including coach, help, support, mentor) |

14 |

|

Professionalism

(including collegiality) |

13 |

|

Decision-making

(including democratic) |

9 |

|

Role-play |

8 |

|

Problem

solving |

5 |

|

Trust

(including rely on) |

4 |

aThree

terms did not fit any categories: find inspiration, important, and wisdom

(which appeared twice).

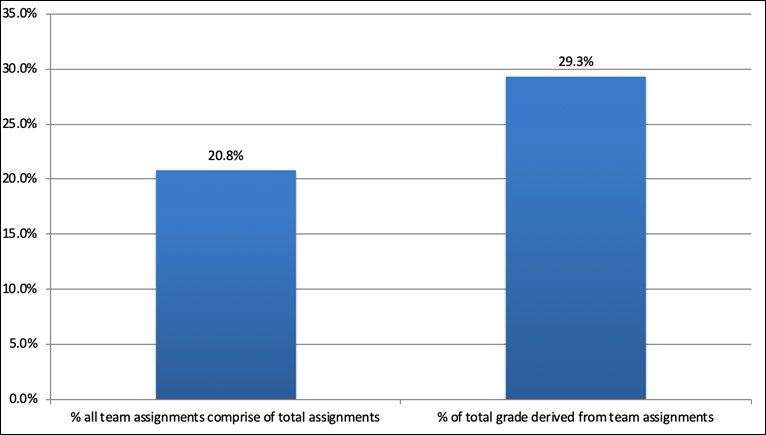

On average, teamwork comprises 29.3% of the total grade,

ranging from 5% to 70%. Most commonly, teamwork comprised 30% of the grade (n

= 33; 38.4%). Eleven course syllabi did not specify the percentage of the total

course grade that teamwork assignments comprised. Teamwork comprised a larger

percentage of total course grades than it comprised of the total number of

assignments (see Figure 1).

Figure 1

Comparison of the percentage that

teamwork comprised of total course assignments to total grade.

The dataset from Campus Labs included IDEA scores for 39

of the 81 courses identified as requiring teamwork (48.2%). While this is a

smaller portion of the courses requiring teamwork than the researchers were

hoping to analyze, analysis was still conducted. The aggregated mean IDEA score

on objective 5 for these courses is 3.96. This is higher than the aggregated

mean IDEA score on objective 5 for all courses in the time period, which was

3.34. Given the size and nature of the sample (i.e., not random), the

statistical significance of this difference could not be tested.

When instructors complete the Faculty Information Form

prior to administering the IDEA evaluation, they are asked to rate the 12 IDEA

objectives as essential, important, or minor to the course. For the 39 courses

in the dataset that required teamwork, 19 instructors selected objective 5 as essential

or important (48.7%), and 17 instructors (43.6%) selected objective 5 as minor

or no importance. The highest aggregated mean score on objective 5 was for

classes in which instructor selected objective 5 as "important"

(4.04), with next highest for instructors who selected "minor/no

importance" (3.97), followed by instructors who selected

"essential" (3.88); see Table 3.

Table 3

Aggregated Mean Score for Courses

Requiring Teamwork by Instructor-Selected Importance of Objective 5

|

Aggregated

Mean Score |

Importance

Selected |

|

4.04 |

Important |

|

3.97 |

Minor/No

Importance |

|

3.88 |

Essential |

|

3.84 |

Default-Impa |

aThis category indicates the instructor did not identify

the objective as essential, important, or minor (i.e., left the selection

blank).

Alumni Perceptions

of Teamwork

While

the interview questions specified “group” and “group work,” alumni responded

using teamwork, group work, collaboration, and other terms interchangeably. A

few interviewees shared very bad experiences in courses with team members who

did not pull their weight, professors who did not help them make a bad

situation better, or where they felt the professor did not want to hear

complaints. Most interviewees reported positive experiences with teamwork in

the program, but they also remembered teamwork happening too often, and one

reported feeling “Wow, we’re in a group again. We’re always in a group.”

The majority of

interviewees recalled enjoying the social aspects of working in teams the most:

meeting new people, forming lasting personal and professional relationships,

collaborating, sharing ideas and perspectives, and appreciating others’

strengths. They enjoyed learning how to work with other people, improving their

communication skills, and learning from other students’ experiences at other

libraries or other library types. Working in a team also afforded greater

support when one person was struggling. It also helped in brainstorming ideas

and in accomplishing more than the team members could alone. On the job,

interviewees reported they enjoy the opportunities they have to collaborate,

share ideas and perspectives, motivate, and inspire each other. They perceive

that teamwork on the job helps to promote productivity and gain a better

understanding of their institution or organization as a whole.

The biggest issue

mentioned about teamwork in classes was scheduling, especially for teams of

more than three people and when one or more members wanted to meet in person

and the others did not want to or could not do that. The second biggest issue

is dealing with the student who does not pull their weight or drops off the

radar. Interviewees wanted to make sure everyone had equal parts and did their

share. When a teammate did not contribute, interviewees indicated they wanted

or needed the professor to get involved or suggested that instructors have a

process and policy set out in advance to handle those situations. During

challenging team dynamics or experiences, they appreciated having a written

team contract to clearly state team expectations and provide a process for

resolving the issues. In addition, peer evaluations eased the tension when team

members were not pulling their own weight and ensured accountability.

Other challenges

reported by interviewees included stress from not being able to reach a team

member, unclear roles and lack of leadership in a team, assignments that did

not lend themselves to teamwork or that did not have a clear relevance for the

job, and having to trust other people to do their part of an assignment.

Regarding leadership, one person noted the challenge could be especially high

in a program with many introverts who do not want to take on a leadership role.

There were also concerns about how to call out people for not doing their share

when you do not know them well and may never have met in person (interviewees

did not specify whether they were recalling face-to-face, hybrid, or online

courses).

Challenges to

working in teams on the job include inability or lack of desire to compromise

or give up control when one has a particularly vivid idea or vision and

frustration when each step needs approval from someone higher up. Interviewees

also dislike difficult power dynamics and confrontation when working in groups

on the job. One said, “There is discord in groups,” so you have to know how to

deal with it.

Interviewees concur

that using teamwork is an everyday part of work in libraries. They said things

like, “Pretty much every library you work at, you're working with a team of

people” and “Group work is a huge part of my career. If you are not able to do

group work as a librarian, you are not going to be happy, build strong

professional connections, or get much done.” Only one interviewee said they

never work in teams, but they had graduated less than a year prior the

interview and had sought committee work to obtain teamwork experience.

Interviewees said teamwork assignments are necessary for the MLIS program but

that the department should take care to actually teach how to work in teams,

use teamwork when appropriate for assignments, and not assign teamwork to

decrease instructors’ grading responsibilities.

The majority of

interviewees believed that teamwork experiences during their MLIS program

influenced their ability to work in teams on the job; only five were not sure

or did not feel that it directly influenced their real world experiences.

Interviewees felt that they were better prepared for real world experiences;

they were able to identify personal strengths and weaknesses, knew when to take

the lead and when to step back, and understood warning signs of team conflict;

they knew how to listen and communicate respectfully, the importance of laying

out expectations, how to use new communication technology, and how to be

flexible.

Interviewees

reported that the program stressed that being a librarian means constantly

sharing and improving on ideas through being an open community. Librarians can

always tap into their networks. Student work in the MLIS program helped formed

the idea that “we’re all in this together towards a common goal” and

librarianship is less competitive than other industries. No matter how annoying

teamwork may be in school, interviewees reported that it is necessary because

it is part of the job. A few disputed this, but mostly they agreed that, “Good

or bad, it’s an extremely valuable learning experience.”

Discussion

Answering the Research Questions

The average IDEA

score on objective 5 in LIS courses that require teamwork (RQ1) is higher than

the overall mean score on that objective across all LIS courses. However, the

difference is less than one point, and the significance cannot be measured

given the limitations of the sample size and quality. The average score on this

objective is higher for instructors who indicate this objective is important

than for instructors who indicate this objective is essential (the

highest-level priority). Follow-up research should investigate instructors’

perceptions of the relationship between the teamwork they assign and their

selection of important and essential objectives.

In LIS courses that

require teamwork (RQ2), teamwork comprises less than three assignments, about

20% of the total class assignments and about 30% of the total class grade, and

it is primarily focused on written and presentation assignments. Only slightly more

than half of courses that use teamwork give any sort of expectations or

learning outcomes in the syllabus, and less than a quarter include best

practices, additional resources, or peer evaluation assignments. It seems that,

in this program, teamwork is utilized but not necessarily taught. The most commonly mentioned topic in teamwork expectations

and learning outcomes is collaboration, which reflects the focus in the

literature on the importance of collaboration in libraries. Here too, future

research should look at instructor perceptions of teaching teamwork, such as

the instructor’s purpose or goal in assigning teamwork.

Over three-quarters

of the alumni interviewees reported that teamwork experiences during their MLIS

program had a positive influence on their ability to work in teams in their

careers (RQ3). While they find compromise, ceding control, and office politics

to be frustrating, they reported that what they learned in the MLIS program

prepared them to identify their own strengths and weaknesses as a team member,

when to step up or step back, and warning signs of impending conflict. They

also learned communication and technology skills that made them better able to

negotiate teamwork in their careers. Critically, alumni reported that the program

helped them see that librarians are constantly collaborating, preparing them

for the realities of their day-to-day work.

Perceived Importance of Teamwork for Librarians

Both the literature

and our alumni report that being able to work in teams, groups, committees, or

other multi-person arrangements is a critical skillset for librarianship. A key

aspect of this is collaboration, which is seen as an “essential skill” (Shah

& Leeder, 2016, p. 609) that is necessary for library work (Calvert, 2018; Laddusaw & Wulhelm, 2018;

Marcum, 2014). Collaboration is the most frequently used term in teamwork

expectations or learning outcomes in the syllabi analyzed for this study, and

it is mentioned in the ALA and LLAMA competencies (ALA, 2008; LLAMA, 2016),

along with other teamwork skills: emotional intelligence, conflict resolution,

and problem solving (LLAMA, 2016).

All but one of the

alumni interviewees reported working in teams on the job. They perceive

teamwork as an essential component of librarianship and library school as a

crucial place to learn how to work with others to achieve a common goal. Alumni

perceive that the program should teach self-assessment, conflict management,

respectful communication, setting expectations, collaborative technology tools,

flexibility, and knowing when to lead or when to go with the flow of the team.

Perception of “Too Much” Teamwork

Even though alumni

perceive teamwork as essential to librarianship and a crucial skillset for the

MLIS program to teach, they also perceive the program as having teamwork in too

many courses. The reality is that teamwork was required in a little over one-third

of the courses in the sample set. The program requires 36 credits (i.e., 12

courses), suggesting that most students would experience 3 to 4 courses with

teamwork. However, because many of the required courses (management, reference,

information science and technology, research methods, and internship) required

teamwork, students may have taken even more courses with teamwork than that.

There are three tracks in the program: school library

media (SLM); libraries, leadership, and transforming communities (LLTC); and

organization of digital media (DM). About 25 to 30% of students are on the SLM

track with 5 to 10% of students on the other tracks at any given time. The

majority of students are not on a track. Depending on the track, students may

have actually taken half or more of their credits in courses that used

teamwork:

·

SLM track. Students

are required to complete management, reference, information science and

technology (or research methods as the requirements shifted from one to the

other during the sample period), school library media, information literacy

instruction, and children’s literature.

·

LLTC track.

Students are required to complete management, reference, information science

and technology or research methods, internship, community relations, and

leadership, and many students on this track elect to take collection

management.

·

DM track. Students

are required to complete management, reference, information science and

technology or research methods, internship, and many students on this track elect

to take collection management and information literacy instruction.

·

General track.

Students are required to take management, reference, information science and

technology, and internship, and many elect to take collection management.

For a student attending

full time (three courses per semester), this could mean one or two courses

requiring teamwork every semester they are in the program. For part-time

students, it could be they are assigned teamwork every other semester or more

often, and any student could be in two courses requiring teamwork concurrently.

One way the

department might tackle this perception of too much teamwork is to tie teamwork

to two required courses to ensure all students have to learn the skills at both

an introductory and reinforcement level, but then strongly suggest it be

avoided in electives. Teamwork could be added to the catalog descriptions of

the two courses so students would know which courses require teamwork and

arrange their schedules accordingly. The department could review the IDEA

objective 5 scores only for the two designated “teamwork” courses to track any

changes on this objective over time.

Another approach is

to change students’ perceptions of teamwork, so they look forward to, or at

least do not dread, teamwork assignments. Improving how teamwork is taught can

help with this (see next section), but the department may need to undertake a

PR campaign as well. The department could record short videos of students and

alumni reflecting on the positive aspects of teamwork in the program and their

careers and show these videos at new student orientation and the beginning of

courses requiring teamwork. Instructors could also ask students at the

beginning of the term to reflect on positive experiences they have had with

teamwork in the past and consider what made those positive and how they can

work with their teammates to replicate what worked previously.

Implications for LIS Curriculum

There is an issue

about the degree to which faculty perceive teaching teamwork as important.

Three of the full-time faculty in the program are the investigators on this

project, but it gives us pause that, even in classes that require teamwork,

faculty do not identify teamwork as an essential learning objective for the

course either on the IDEA instrument or their syllabus. Might that be due to

the fact they are not explicitly teaching teamwork skills or due to the low

percentage teamwork assignments comprise of total course assignments and

grades? How can we garner faculty buy-in for a focused effort on teaching

teamwork?

Our alumni tell us

that teamwork is a critical skill for librarianship and that our students need

to be prepared to be effective members of teams when they graduate, and the

literature supports this. But how do we teach the soft skills of teamwork? It

is clear from this research that we have considerable room for growth in this

area. For example, peer evaluation assignments are considered a teamwork best

practice (Capdeferro & Romero, 2012; Roy &

Williams, 2014; Xu et al., 2013), but they were used in only about 15% of

courses that employed teamwork assignments. None of the syllabi indicated that

the courses are actively teaching the specific teamwork skills alumni identify

having learned. The required management course did cover the topic of managing

teams for one week, but are we truly expecting our students to learn how to

communicate, negotiate, and lead in teams without formal training? Also, alumni

report the biggest issues of teamwork are scheduling and managing teammates who

do not do their fair share of work; yet these topics are rarely covered in

teamwork expectations and learning outcomes in course syllabi.

Based on the findings, the investigators in this study

are designing a teamwork instructional module that can be utilized in any

course in the program. The goal of this module is to make it easy for faculty

to teach teamwork without adding the burden of an additional topic to their

teaching load and to provide a consistent teamwork language and approach across

the MLIS curriculum. The module includes a lesson on teamwork covering

definitions and benefits of teamwork, what kind of teammate you are, and

strategies for working as part of a team; a quiz faculty can adopt as either a

formative or summative assessment; a sample team contract template; and a

sample peer evaluation instrument. One of the members of the research team

implemented team contracts in spring 2016, and some of the alumni who were

interviewed referred to that document as smoothing over a lot of potential

areas of conflict among team members. Other faculty have since adopted a team

contract and anecdotally report fewer instances of needing to step in to help a

team resolve conflict. The module is being piloted, and results will be

reported in future publications.

Limitations

This study focused

on the perceptions of alumni from one MLIS program so the results cannot

necessarily be generalized beyond our own students and alumni. However, the

make-up of the student body at most U.S. LIS schools is similar, and it is

likely that the learning styles of students in one program mirror the learning

styles of students in other programs. There is some question about why our

alumni reported such positive experiences with teamwork in their program when

the literature indicates one should expect otherwise. It is possible that the

gap in time between being a student and working in the professional world could

have mitigated feelings of stress and frustration. Also, alumni who volunteered

to be interviewed may be more likely to work better in teams, work well with

others, and feel comfortable taking on responsibility than the student who goes

missing during an assignment or drops out of the program.

Conclusion

Teamwork is

prevalent in all aspects of the library field. It is critical for students in

LIS programs to develop teamwork skills so they can be successful in their

jobs. Librarians need to be able to collaborate internally within their

libraries and forge external collaborations beyond their libraries to secure

grant funding, develop partnerships, and promote advocacy. Assigning team

projects does not guarantee students will develop the teamwork skills they

need. LIS schools can follow the lead of the business management field that has

specifically researched how to teach teamwork (Rafferty, 2013; Snyder, 2009; Yazici, 2005). Taking an active role in teaching skills in

scheduling, time management, personal accountability, and peer evaluation may

help overcome the limited way this LIS school is currently teaching teamwork.

Other questions still need to be investigated, such as instructors’ perceptions

of teamwork as an essential learning objective and ways to make teamwork

assignments more successful for students. This assessment project is a first

step in the direction of developing a program-wide curriculum that prepares LIS

students to be productive and effective members of teams, groups, committees,

collaborations, and partnerships in their careers.

References

American Library Association. (2008). Core

competencies. Retrieved from http://www.ala.org/educationcareers/careers/corecomp/corecompetences

Bello, L., Dickerson, M.,

Hogarth, M., and Sanders, A. (2017). Librarians doing DH: A team and project

based approach to digital humanities in the library. Collaborative Librarianship, 9(2), 97–103. Retrieved from https://digitalcommons.du.edu/collaborativelibrarianship/vol9/iss2/6/

Bernier, A., & Stenstrom, C. (2016). Moving from chance and “chemistry” to

skills: Improving online student learning outcomes in small group

collaboration. Education for Information,

32, 55–69. https://doi.org/10.3233/EFI-150960

Calvert, K. (2018).

Collaborative leadership: Cultivating and environment for success. Collaborative Librarianship, 10(2),

79–90. Retrieved from https://digitalcommons.du.edu/collaborativelibrarianship/vol10/iss2/4/

Capdeferro, N., & Romero, M. (2012). Are online learners

frustrated with collaborative learning experiences? The International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning, 13(2),

26–44. https://doi.org/10.19173/irrodl.v13i2.1127

Cole, M. (2017). What

collaboration means to me: Collaboration as a cocktail. Collaborative Librarianship, 9(2), 74–76. Retrieved from https://digitalcommons.du.edu/collaborativelibrarianship/vol9/iss2/2/

Evans, G. E., & Alire,

C. A. (2013). Management basics for

information professionals (3rd ed.). Chicago, IL: Neal-Schuman.

Henricks, S. A., & Henricks-Lepp,

G. M. (2014). Desired characteristics of management and leadership for public

library directors as expressed in job advertisements. Journal of Library Administration, 54(4), 277–290. https://doi.org/10.1080/01930826.2014.924310

Kim, J., & Lee, J. (2014).

Knowledge construction and information seeking in collaborative learning. Canadian Journal of Information and Library

Science, 38(1), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1353/ils.2014.0005

Laddusaw, S., & Wilhelm, J. (2018). Yours, mine and ours: A

study of successful academic & public library collaboration. Collaborative Librarianship, 10(1),

30–46. Retrieved from https://digitalcommons.du.edu/collaborativelibrarianship/vol10/iss1/6/

Library Leadership and Management Association (LLAMA).

(2016). Leadership and management competencies. http://www.ala.org/llama/leadership-and-management-competencies

Mandel, L. H. (2017).

Aggregated IDEA data for LSC courses, fall 2010-spring 2016. Retrieved from https://harrington.uri.edu/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/AggregateIDEAdata-Report_revised.pdf

Marcum, D. (2014). Archives, libraries, museums: Coming back together? Information & Culture, 49(1), 74–89.

https://doi.org/10.7560/IC49105

McKinney, P., & Cook, C.

(2018). Student conceptions of group work: Visual research into LIS student

group work using the draw-and-write technique. Journal of Education for Library and Information Science, 59(4),

206–227. https://doi.org/10.3138/jelis.59.4.2018-0011

O’Farrell, M., & Bates, J.

(2009). Student information behaviours during group

projects: A study of LIS students in University College Dublin, Ireland. Aslib Proceedings, 61(3), 302–315. https://doi.org/10.1108/00012530910959835

Oliveira, I., Tinoca, L., & Pereira, A. (2011). Online group work

patterns: How to promote a successful collaboration. Computers & Education, 57, 1348–1357. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2011.01.017

Rafferty, P. D. (2013) Group

work experiences: Domestic MBA student experiences and outcomes when working

with international students. Journal of

Further and Higher Education, 37(6), 737–749. https://doi.org/10.1080/0309877X.2011.645470

Roy, L., & Williams, S.

(2014). Reference education: A test bed for collaborative learning. The Reference Librarian, 55(4), 368–374.

https://doi.org/10.1080/02763877.2014.929923

Saines, S., Harrington,

S., Boehringer, C., Campbell, P., Canter, J., & McGreary,

B. (2019). Reimaging the research assignment: Faculty-librarian collaborations

that increase student learning. College

and Research Libraries News, 80(1), 14–17, 41. https://doi.org/10.5860/crln.80.1.14

Shah, C., & Leeder, C. (2016). Exploring collaborative work among

graduate students through the C5 model of collaboration: A diary study. Journal of Information Science, 42(5),

609-629. https://doi.org/10.1177/0165551515603322

Snyder, L. G. (2009). Teaching

teams about teamwork: Preparation, practice and performance review. Business Communication Quarterly, 72(1),

74-79, https://doi.org/10.1177/1080569908330372

Xu, J., Du, J., & Fan, X.

(2013). Individual and group-level factors for students' emotion management in

online collaborative groupwork. Internet

and Higher Education, 19, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iheduc.2013.03.001

Yazici, H.J. (2005). A study of collaborative learning style

and team learning performance. Education

& Training, 47(2/3), 216–229. https://doi.org/10.1108/00400910510592257