Table 1

Student Enrollment and Consultation Statistics

|

Semester

|

Students Enrolled

in Coursea

|

Total Teamsa

|

Teams Who Met With a Librarian

|

|

Fall

2017

|

173

|

49

|

27

|

|

Spring

2018

|

171

|

47

|

47

|

|

Fall

2018

|

169

|

44

|

43

|

aEnrollment numbers and number of teams were provided by the course

instructor.

Due to the increasing amount of librarian time devoted to

the consultations and the demand for library space, the second author started

considering alternate ways of providing the consultations. Before making

changes, the second author wanted to assess the consultations. We had robust

usage statistics about the numbers of students coming for consultations and use

of the course guide (Stephens, Melgoza, Hubbard,

Pearson, & Wan, 2018), but this data provided no information about the

effectiveness of the instruction or the logistics of the consultations.

To plan the assessment, the second author asked the first

author for assistance because she had assessment experience and was a neutral

party who did not provide consultations for this course. From the outset,

analyzing student papers would not be an option because the course instructor

preferred not to share the final student papers with the librarians. After an

initial review of the consultation assessment literature, we determined that we

did not have a clear path for determining the best assessment method. We wanted

a method that would allow us to know more about the information students were

remembering and applying from the consultations, as well as how students felt

about the consultation experience. Thus, we developed this action research

project to evaluate different research consultation assessment methods.

Literature Review

Consultation Assessment

Librarians have used various methods to assess research

consultations including surveys (e.g., Butler & Byrd, 2016; Drew & Vaz, 2008), usage statistics (Fournier & Sikora, 2015),

citation analysis (e.g., Hanlan & Riley, 2015; Reinsfelder, 2012), pre and post testing (e.g., Sikora,

Fournier, & Rebner, 2019), focus groups (e.g.,

Watts & Mahfood, 2015), interviews (e.g., Rogers

& Carrier, 2017), mystery shoppers (e.g., Newton & Feinberg, 2020), and

examining students’ course grades (e.g., Cox, Gruber, & Neuhaus, 2019;

Newton & Feinberg, 2020). While most of these articles discuss the

limitations of the particular method, direct comparison of different

consultation assessment methods is limited. Even when researchers used multiple

consultation assessment methods, the discussions focused on the findings of the

method, not the utility of each method (e.g., Hanlan

& Riley, 2015; Newton & Feinberg, 2020; Watts & Mahfood,

2015).

Only Fournier and Sikora’s (2015) scoping review provided

an explicit discussion of the strengths and weaknesses of the three

consultation methods they identified: usage statistics, surveys, and objective

quantitative methods. Usage statistics are useful for understanding the demand

and planning the service (Fournier & Sikora, 2015). Surveys can show user

satisfaction and assist in making modifications to the service, but are limited

by their subjective nature and positively skewed results (Fournier &

Sikora, 2015). Statistics and surveys are not the best methods to use to

provide evidence of the outcomes of research consultations. Rather, objective

quantitative methods, like pre/post testing, provide a better way to assess the

impact of consultations on student learning (Fournier & Sikora, 2015).

Since the use of objective quantitative methods would be challenging in our

context, we looked for other ways to assess the outcomes and logistics of

consultations.

Qualitative methods offer an alternative way to assess

the outcomes and logistics of consultations. Both interviews and focus groups

have been used to provide evidence of what students believed were the outcomes

of research consultations (Watts & Mahfood, 2015;

Yee et al., 2018). Interviews can be an initial step in creating a survey and

can provide detailed information about outcomes students felt as a result of

consultation (Yee et al., 2018). Open-ended survey questions can elicit

responses about how students perceive the value of consultations (Magi & Mardeusz, 2013).

Action Research and

Assessment

Action research is a method of inquiry that aims to

improve practice (Malenfant, Hinchliffe, &

Gilchrist, 2016; Reason & Bradbury, 2006; Suskie,

2018). Action research projects focus on an issue derived from a specific

context, are led by the librarian involved in the service, incorporate stakeholders

in their design, make changes immediately based on the results, and utilize an

evolving design (Coghlan & Brydon-Miller, 2014; Malenfant

et al., 2016; Woodland, 2018).

Action research aligns well with library assessment

projects. The unique contextual factors within an academic library often drive

assessment projects. Librarians and other stakeholders involved in the delivery

of a service plan, evaluate, and make changes to the service based on the

assessment data.

Action research has been used in the library and

information science discipline as the basis of assessment projects. Multiple

researchers have used action research to assess information literacy

instruction (e.g., Insua, Lantz, & Armstrong,

2018; LeMire, Sullivan, & Kotinek,

2019; Margolin, Brown, & Ward, 2018). In addition, researchers have used

action research for other types of assessment including the enhancement of

services (Kong, Fosmire, & Branch, 2017) and

planning library spaces (Brown-Sica, 2012; Brown-Sica, Sobel, & Rogers, 2010). Using action research to

determine a way to assess our consultations would allow us to build upon the

hallmarks of the assessment cycle, while incorporating the aspects of action

research that would keep our research design flexible as we encountered new

information. Our study adds to the literature on consultation assessment by

directly comparing four assessment methods in terms of the data collected about

the instruction and logistics as well as the ability to implement the method.

Aims

The aim of this action research project was to determine which assessment

method would be the best way for us to collect actionable feedback in order to

continuously improve the team research consultations. The goals of the

assessment were to assess the effectiveness of the instruction and the

logistical aspects of the consultation service in order to maximize the use of

available resources.

Each assessment method was evaluated on three criteria:

information provided related to the effectiveness of the instruction,

information provided about the logistics of the consultation, and suitability

as an assessment method. We defined effectiveness of the instruction by

evaluating if what students reported learning from the consultation was related

to the consultation learning outcomes. The logistics of the consultation was

defined as student opinions about the timing of the consultation in relation to

the assignment milestones, the length of the consultation, and the format of

the consultation. The suitability of the assessment method was determined by

considering the usefulness of the information collected and the amount of staff

time needed to implement the assessment.

Methods

We planned to implement one-minute papers, team process

interviews, and focus groups as our assessment methods. One-minute papers are

frequently used as an assessment technique in library instruction sessions

(Bowles-Terry & Kvenild, 2015). Given their popularity

in classroom assessment, we found limited discussion of the use of one-minute

papers as an assessment technique for consultations. One-minute papers

typically consist of two questions: one focused on what students learned and

the other focused on what was confusing.

We chose the one-minute paper because it would allow us

to assess students’ recall of information immediately after instruction.

However, our Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval come too late in the

fall 2017 semester to use the one-minute papers immediately after the

consultation. Instead, we used the IRB-approved one-minute paper questions on

the end of semester questionnaire in fall 2017. We did not initially plan to

use a questionnaire to assess the consultations, but took advantage of an

opportunity provided by the course instructor. Once we starting using the

one-minute paper after the consultation, we changed the questions on the

questionnaire.

Interviews and focus groups were chosen because we

thought they would provide more in-depth responses from students. These methods

had been used by other universities examining how consultations impact student

learning (Watts & Mahfood, 2015; Yee et al.,

2018). Two studies that used citation analysis concluded that qualitative data

from the students about their research process would have been helpful to

understand the results (Hanlan & Riley, 2015;

Sokoloff & Simmons, 2015). Based on these studies, we decided to use team

process interviews to explore the process that teams used to find information

at different points in the assignment. We planned to use focus groups in order

to engage students in conversation about the consultations.

Action Research Cycle

We used action research as a way to evaluate the

assessment methods for team research consultations. Action research includes a

cycle of planning, acting and observing, reflecting, re-planning, acting and

observing, and reflecting (Kemmis, McTaggart, & Nixon, 2014, p. 18). We planned

how to collect data using one-minute papers, questionnaires, focus groups, and

team process interviews. We acted and

observed our implementation of the assessment methods. Then, we reflected on the utility of the methods,

compared the results of the assessments, and made changes to the assessments

and the consultations. Reflection occurred throughout the semester. We talked

at least once a week about how the assessments and the consultations were

going. Small changes to the consultations and the assessment methods were made

immediately based on the assessment data and personal observations. Larger

changes to the consultations were made after each semester.

Stakeholders

We had three groups of stakeholders: the course

instructor, librarians, and students. After we informed the course instructor

of our assessment project, he offered his support and willingness to assist as

needed. The instructor gave us a portion of the last class each semester to

distribute the questionnaire. Each semester we shared student responses to

illuminate students’ confusion with the project and our changes in instruction.

Librarians assisted with the data collection for the

one-minute papers and the questionnaires. After collecting the one-minute

papers, some librarians reviewed the responses to see what the students

retained. Some of the group reviewed the questions on the questionnaire.

Librarians received a summary of themes from the assessments as well as

representative responses prior to the start of consultations for the next

semester. The group discussed changes to make for the consultations based on

the findings.

The students were not as involved as one would expect for

an action research project. Prior to distributing the questionnaire, we shared

our past findings and asked students to share their honest assessment of our

instruction and changes.

Data Collection and Data Analysis

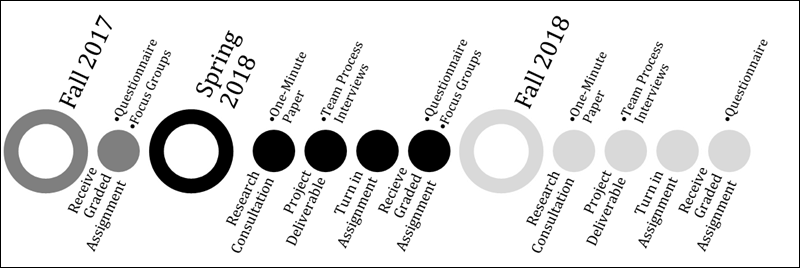

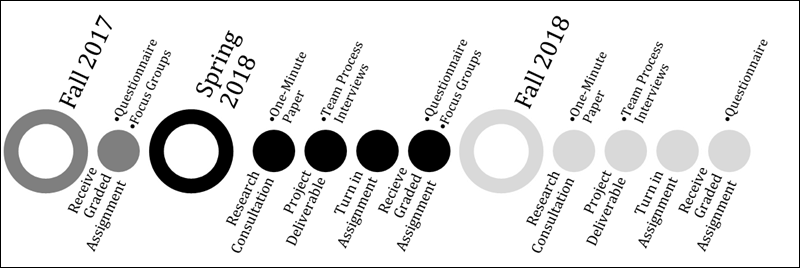

Our data collection spanned three semesters; it began in

fall 2017 and ended in fall 2018. We used each assessment method at a different

point in the assignment (see Figure 1). The participants were junior and senior

engineering students who were currently enrolled in the engineering course

Figure

1

Timeline

of planned data collection and assignment milestones.

One-Minute Papers

The one-minute paper assessed the immediate impact of the

instruction. One-minute papers were distributed to individual students after

their team’s research consultation for two semesters, spring 2018 and fall

2018. The first author met individually with each librarian conducting research

consultations to explain the data collection process and answer any questions.

The librarian who conducted the consultation distributed the one-minute paper

in hardcopy to students immediately after the consultation. The librarian

stepped away from the table to give students privacy. Students’ participation

was voluntary, no incentives were used to increase participation, and student

responses were anonymous. The librarian collected the one-minute papers and

gave them to the first author for transcription and data analysis. We received

77 completed one-minute papers (see Table 2).

In spring 2018, we piloted four versions of the

one-minute paper in order to determine the questions that would provide the

most useful information. Librarians gave the different versions to the students

randomly. Table 3 presents the questions on the four versions and number of

responses per version. After analyzing the spring 2018 data, we found that

student responses to question 2 on version 2 were the most useful for

highlighting additional topics to cover during the research consultation. The

first question on each of the versions elicited similar responses from

students. Therefore, we only used version 2 of the one-minute paper in fall

2018.

The first author transcribed and analyzed the data from

the one-minute papers. The coding followed the qualitative coding procedures

outlined in Creswell and Guetterman (2019): noting

words and phrases, assigning a descriptive code to the phrase, defining each code,

merging similar codes, and developing themes by aggregating the codes. Codes

focused on resources and information that students described learning during

the consultation. The codes were both descriptive terms and in vivo codes,

which are code labels that use the same language from the student’s responses

(Creswell & Guetterman, 2019). Each question was

coded independently. Then, the codes for the first questions on each version

and the codes for the second questions on each version were pooled to develop

themes. The first author coded the data in ATLAS.ti

each semester. After the initial coding each semester, we met to discuss the

themes that emerged from the data.

Table 2

Participants by Semester

|

Semester

|

One-Minute

Papers

|

Team

Process Interviews

|

Questionnaires

|

Retrospective

Interviews

|

|

Total

Number

|

Met

with Librarian

|

Did

Not Meet with Librarian

|

|

Fall 2017

|

n/a

|

n/a

|

57

|

38

|

19

|

0

|

|

Spring 2018

|

52

|

7 (3 teams)

|

68

|

57

|

11

|

3

|

|

Fall 2018

|

25

|

3 (1 team)

|

95

|

93

|

2

|

n/a

|

|

Total

|

77

|

10 (4 teams)

|

220

|

188

|

32

|

3

|

Table 3

One-Minute Paper Questions

|

Version

|

Questions

|

Spring

2018 Responses

|

Fall

2018 Responses

|

|

1

|

1. What

do you think you will do differently after meeting with a librarian?

2. What

is still unclear about using library resources for your assignment?

|

17

|

|

|

2

|

1. What

did you learn?

2. What

would you like to learn more about?

|

15

|

25

|

|

3

|

1. What

was helpful?

2. What

was not helpful?

|

10

|

|

|

4

|

1. What

was the most important thing you learned during this consultation?

2. What

question remains unanswered?

|

10

|

|

Team Process Interviews

Team process interviews investigated how teams worked

through the assignment. The second author recruited teams during the team’s

initial research consultation with her. Project reports were due about every

two weeks, and the interviews were scheduled for the day after a project report

was due, for a total of three interviews. The interviews were held in one of

the library’s consultation rooms and snacks were provided. The same five

questions were asked during each interview. Questions focused on what type of

information the team used to meet the requirements of the previous progress

report and what kind of information the team needed to find for the next

progress report (see Appendix A). The second author took notes during the

interview; interviews were not recorded. After each team process interview, we

debriefed to discuss the data. The notes were analyzed for trends that could

inform the instruction and the logistics of the consultation.

Four teams (A, B, C, and D) participated in the team

process interviews. All members of a team were encouraged to attend each

interview. In spring 2018, the second author recruited three teams. Team A had

the same, single student attend all sessions. Team B had four members attend

the first session, three the second, and two the last session. Team C had the

same two students attend all sessions. In fall 2018, only one team (D) was recruited.

Three students attended the first session, and the same two students attended

the last 2 sessions. The team process interview took 10 minutes and afterwards

the second author asked the students if they wanted to stay for an additional

consultation. All of the teams did stay for the consultation. They discussed

their outline and asked for additional tips for locating the next set of

information.

Questionnaires

The questionnaire gathered feedback from the students who

had met with a librarian and from the students who had not met with a

librarian. We collected data using the questionnaire in fall 2017, spring 2018,

and fall 2018. The paper questionnaire was distributed to the students

attending the last class session of the semester. Students received their

graded project after the questionnaire was completed. A food incentive was

provided, but students were not required to participate in order to have the

incentive. The questionnaires were printed on different colors of paper to

better keep track of those who met with a librarian and those who did not meet

with a librarian. All questionnaire responses were anonymous. We collected 220

questionnaires (see Table 2).

Since we were using action research, the questions

naturally changed as we instituted modifications based on the questionnaire

responses (see Appendix B). We dropped questions and added new ones. The fall

2017 questionnaire questions were based on the one-minute papers questions with

added questions about citations. The spring 2018 questionnaire for students who

had a consultation had questions that addressed the effectiveness of the

instruction and the logistics. The questions included the information students

learned from their consultation, what they could apply to future courses, and

their feedback on having another team present during the consultation. For the

students who did not meet with a librarian, we asked if any member of the team

met with a librarian and if they shared any information, how they chose their

topic, the search process and where the information was found, and if they were

aware of the course guide.

For the fall 2018 questionnaire, we only made changes to

the questions about the logistics of the consultation. The new questions were

about their experience with a shorter consultation time, how often they met

with a librarian, if they had needed to consult with a librarian in another

engineering course, and feedback on the online tutorials. For the group that

did not meet with a librarian, the new questions were about the tutorials and

if they struggled to find information for their project.

After data transcription, the data analysis for the

questionnaires followed a similar procedure to the one-minute papers. For

open-ended questions, the first author used the qualitative coding procedures

outlined in Creswell and Guetterman (2019). All

responses for each question were pooled for analysis, but each question was

analyzed separately. The first author used ATLAS.ti

to apply the code labels to the student responses each semester. The list of

code labels in ATLAS.ti provided a starting point for

coding each semester, and additional codes were added when needed. For the

questions that had a closed ended component, the first author used a set coding

scheme (e.g., yes, no, maybe) to code the closed ended answer and analyzed the

data using descriptive statistics.

Focus Groups/Retrospective Interviews

Planning Focus

Groups

After the team project was completed, we wanted to use

focus groups to solicit feedback on the instruction and the timing of the

consultation. Our focus group recruitment was unsuccessful in fall 2017. We

attempted to recruit students who had a research consultation via email, but we

did not have an email address for every student who met with a librarian. We

scheduled multiple time slots during the day and evening in the last full week

of classes and offered an incentive of pizza, but no students indicated

interest in participating. After the unsuccessful email recruitment, we tried

to hold focus groups during the class meeting time on the last class day, but

again no students were interested in participating.

For the spring 2018, we changed our recruitment method

and added additional incentives. At the consultation sessions, we obtained the

emails of all the present team members. The focus groups were scheduled for the

days immediately following the questionnaire distribution. We recruited

in-person when we went to distribute the questionnaires on the last class day.

If a student indicated interest in participating, we handed them a slip of

paper with instructions for signing up. We also offered a $10 gift card in

addition to lunch. Using the new recruitment technique, we had three students

volunteer.

Conducting and

Analyzing Retrospective Interviews

Since we did not get enough volunteers to hold focus

groups, we held two retrospective interviews. The first interview had two

participants. The second interview only had one participant because this

student had been a part of the team process interviews. We felt this student’s

experience would be different from the other students and wanted to keep the

participants with similar consultation experiences together. The first author

conducted the interviews, and another library staff member, who did not provide

consultations, observed. The same protocol was used for both interviews (see

Appendix C). The retrospective interviews were audio recorded. Both the first

author and the library staff member took notes during the interview. As soon as

possible after each interview, the first author transcribed the notes and added

additional details and observations. A summary-based approach was used for the

data analysis (Morgan, 2019). To do this, the first author compared the

responses from each interview in order to summarize the information that could

inform the instruction provided and the logistics of the research consultation.

Results

The results are discussed by data collection method. For

each method, we highlight how the collected data showed the effectiveness of

the instruction, informed the logistical aspects of the consultation, and

contributed to our analysis of the suitability of the method.

One-Minute Papers

Relating to the effectiveness of the instruction, the

one-minute paper responses to the first question on each version (see Table 3)

fell into three primary themes: resources and services, how to use the library

or resources, and related to the assignment (see Table 4).

The analysis of one-minute paper responses to the second

question on each version showed certain questions would elicit more actionable

responses. Students did not answer questions that were negative in nature (e.g.,

“What is still unclear about using library resources for your assignment?”,

“What was not helpful?”). Typical responses to these questions were “none,”

“n/a,” or positive responses, like “everything was explained thoroughly.” The

positively framed “What would you like to learn more about?” question provided

the most actionable responses. The responses were primarily about the

assignment, but a few were about utilizing library resources. For example,

“proper citations” and “maybe more specifics on key search words and which

phrases might be the most effective in searching.”

Table

4

Example

Student Reponses for One-Minute Paper Themes

|

Theme

|

Examples of Student

Reponses

|

|

Resources

and services

|

·

Databases

·

Library

resources

·

RefWorks

·

EndNote

|

|

How

to use the library or resources

|

·

Using

combinations of words to search

·

Navigating

through databases

|

|

Related

to the assignment

|

·

Topic

needs to be narrowed down

·

How

to structure the paper

·

Best

way to organize/approach paper

|

The one-minute papers were an effective method for

collecting data about the immediate effectiveness of the instruction, but not

about the logistics of the consultation. Therefore, this method would not fit

both of our needs for effectiveness of the instruction and logistics of the

consultation. This assessment method also had implementation challenges. While

all librarians providing the consultations were willing to hand out the

one-minute papers, not everyone did so consistently. In addition, we had to

coordinate a centralized location to collect the responses and plan time to

transcribe the data.

Team Process Interviews

All four teams had different topics but still

approached the project similarly. Initially, the teams felt that the first

consultation was sufficient for them to complete their project. Though they

agreed for their team to be interviewed, they really wanted continued access to

the librarian in case they needed additional instruction.

In the first session of the team assessment, none of

the teams demonstrated a complete understanding of the scope of the project.

With each session, the teams gained confidence with understanding the scope of

the project and used their newfound searching techniques to find information

for the forthcoming project sections. Other times, they struggled to compose

searches for previously unexplored aspects of their topic.

As suspected, the teams were not following the course

instructor’s timetable for writing the paper; they did not understand or

embrace how the progress reports schedule was leading them to write their paper

at a manageable pace. Sometimes the teams did not submit what the course

instructor required because they had competing assignments from other courses.

Teams appreciated having a regularly scheduled, structured appointment to

discuss the project and get more focused information for each project

submission. There was no consensus as to when a second library consultation

should be offered.

This method was better suited to understanding how the

teams work on the project, and therefore, should not be used for measuring the

effectiveness of the instruction and logistics of the consultation. The team

process interviews were an effective method for collecting data about how the

teams’ research needs changed during the project, but did not need to be

continued once we found similar results both semesters. The team process

interviews would be good to use again if there were fundamental changes to the

assignment. The high time commitment was also a disadvantage. While all teams

could schedule up to two consultations, the personalized assistance given to

the teams who agreed to be interviewed could give those teams an advantage.

Questionnaires

At the end of the semester, students’ responses to the

most important things they learned during the consultation focused on three

themes: the assignment, awareness of library resources, and utilization of

databases and resources. When answering about what they learned that could be

used in future courses, student responses fell into two primary themes:

awareness of library resources and utilization of databases and resources.

Responses from students who did not personally meet with

a librarian, but had team members who met with a librarian, supported the

themes. These students responded that their teammates shared which databases to

use and advice for choosing a topic.

In regard to the logistics of the consultations, student

responses showed that they appreciated the personalized nature of the

experience, including the focus on only their topic and the ability to ask

specific questions about their topic. Feedback to the idea of a librarian

meeting with multiple teams at once was mostly negative. After shortening the

consultations to 30 minutes in fall 2018, the majority of the responses

indicated that the 30-minute length of the consultation was sufficient.

However, a third of the responses expressed that students would like longer

consultations or that 30 minutes is only sufficient in certain cases.

Table

5

Example

Student Reponses for Questionnaire Themes

|

Theme

|

Examples of Student

Responses

|

|

Assignment

|

·

How

to layout our paper and what to focus on

·

Ability

to narrow down a research topic using library resources

|

|

Awareness

of library resources

|

·

How

to access the research databases

·

about

the wide variety of sources that were available

·

I

could go there for research paper help. I had no idea that was possible.

|

|

Utilization

of databases and resources

|

·

Keywords

to search with to find sources directly related to my topic

·

Research

more effectively with credible resources

|

The questionnaire assessment method was suitable for

assessing both the effectiveness of the instruction and the logistics of the

consultations. This method allowed us to modify the questions each semester to

collect data needed at that particular time. The challenges with the

questionnaire method were writing questions in a way that elicited useful

student responses, recruiting library staff to help with the in-class data

collection, and deciphering and transcribing students’ handwritten responses.

Collecting data required a half-day time commitment of multiple librarians, but

we were able to gather evidence from a meaningful portion of the students at

one time. The continued use of this method depends on the continued support of

the course instructor to allow us to collect data during class time.

Retrospective Interviews

In regard to the effectiveness of the instruction, we

learned about what students believed were the outcomes of the consultation and

the amount of general library information to be covered. Students saw

assistance in helping them decide which topic to choose as the primary outcome

of the consultation. Students felt that the consultations helped them have a

better understanding of the types of information sources that were appropriate

for the course paper. This included sources that are not necessarily scholarly,

like patents, websites, and contacting industry people directly. The students

disagreed about the amount of general library information that should be

provided during the consultation.

The retrospective interview participants’ responses about

the logistics of the consultations gave us additional insight about student

expectations about the consultations and accessing resources. Participants

mentioned preparation both in regard to the librarian and the students.

Students expected the librarians to already know the good resources for the

topic and share their personal experiences with the project. Students also

realized they personally needed to prepare beforehand to fully take advantage

of the research consultation. The participants strongly preferred that a

librarian only meet with one team at a time. Students gave no clear answer

about the timing of consultations.

Focus groups were not a suitable method to collect

assessment data for our research consultations. While we appreciated the

in-depth responses provided by students about the effectiveness of the

instruction and the consultation logistics, the challenge of recruiting

students outweighed the insights we gained. Due to the low participation, the

amount of coordination required, and scheduling conflicts, we never conducted

any focus groups and we only conducted retrospective interviews one semester.

Discussion

Comparing Data for Effectiveness of Instruction

We found that the one-minute papers and the

questionnaires were the best methods to assess the effectiveness of the

instruction. Students’ answers to both of these assessments aligned with the

learning outcomes for the consultations: learn about the breadth of resources

provided by the library and how to search the resources. Mapping student

responses to learning outcomes is one way to analyze one-minute papers to

determine if the instruction is meeting its objectives (Bowles-Terry & Kvenild, 2015). In the one-minute papers and the

questionnaires, the same themes were found in student responses about what was

learned, which demonstrated in our case the timing of the assessment did not

influence the responses. One strength of the questionnaire was that the timing

at the end of the semester allowed for a better understanding of whether

students continued to use what they learned in the consultation (Goek, 2019). However, when only using the questionnaire at

the end of the semester, any changes to instruction had to wait until the next

semester.

The retrospective and team process interviews provided

the most detailed information about student beliefs about what they learned.

From the retrospective interviews, we learned how students applied information

from the consultation to complete the assignment, and the team process

interviews helped us understand how students worked through the project and the

challenges they encountered with finding information for the assignment. In

order to make better use of the interviews, we could ask questions to clarify

and provide context to the questionnaire responses, like other researchers have

suggested (Hanlan & Riley, 2015; Sokoloff &

Simmons, 2015).

Comparing Data for Logistics of Consultations

In terms of assessing the logistical aspects of the

consultation, the questionnaire again provided us with the best assessment

method. The questionnaire was easy to modify each semester to solicit student

feedback on ways to modify the consultation service. The use of questionnaires to

inform consultation logistics supports Newton and Feinberg’s (2020) finding

that a survey was a good method to assess student satisfaction with the

consultations in regard to scheduling and the location of the consultation.

The one-minute paper offered no information about the

logistics, but the team process interviews and the retrospective interviews

provided some student feedback about the logistics. While the retrospective

interviews provided us with preferences about the consultation logistics, self-selection

bias might have influenced the results. Students were aware of us seeking

information about meeting with multiple teams at once prior to the focus group.

Students participating in the team process interviews might have been

influenced by the desire to have more personalized assistance. Self-selection

bias is a limitation that other researchers using interviews have also noted

(e.g., Rogers & Carrier, 2017).

Comparing Utility of Methods

In regard to the utility of each method in our context,

we determined that the questionnaire was the best method for our environment

due to the data collected and our ability to distribute the assessment (see

Table 6). Questionnaires are one of the most frequently used methods to assess

research consultations (Fournier & Sikora, 2015). We identified three

reasons why questionnaires were the most suitable assessment method in our

context, which provide additional insight into why questionnaires are often

used. First, the questionnaire allowed us to collect data about the

effectiveness of the instruction and the logistics of the consultation. The

questions could easily be modified to meet our needs at a particular time. To

continue to provide actionable data, the questions should not focus on user

satisfaction, which has been shown to receive positive responses (Fournier

& Sikora, 2015; Newton & Feinberg, 2020). Positive feedback is

flattering, but does not identify areas for service improvement. The

questionnaire also allowed us to collect data from students who did not meet

with a librarian.

Second, the distribution of the questionnaire was more

streamlined than other methods. Since we distributed the questionnaires once

each semester, the method avoided the challenges we encountered with the

one-minute papers. As the questionnaire was distributed at the beginning of the

class, we had a high response rate. Our experience supports Faix,

MacDonald, and Taxakis (2014) who found they got a

better response rate when distributing the survey in class.

Third, the data analysis of the questionnaires was the

easiest to integrate into our workflows. While the questionnaires took a few

weeks to completely transcribe and analyze, the different topics of questions

allowed us to prioritize the analysis of the questions, if required, to gather

the information needed to make changes to the consultations. The one-minute

papers also required a time commitment to transcribe and code the responses,

and this analysis needed to occur immediately to make changes to the ongoing

instruction. We only had time to do summaries of the interview data before

needing to make changes for the next semester, which meant some of the data we

collected was not utilized.

Table

6

Methods Evaluation Summary

|

Method

|

Effectiveness

of Instruction

|

Consultation

Logistics

|

Utility

of Method

|

|

One-minute papers

|

Best learning

outcomes data

|

No data

provided

|

Some utility

|

|

Team process interviews

|

Limited

learning outcomes data

|

Limited actionable

data

|

Difficult

implementation

|

|

Questionnaires

|

Best learning

outcomes data

|

Best

actionable data

|

Best utility

|

|

Focus Groups

|

N/A

|

N/A

|

Difficult

implementation

|

|

Retrospective interviews

|

Limited

learning outcomes data

|

Limited

actionable data

|

N/A

|

Changes Made to Consultations

The fall 2017 questionnaire led to instructional changes

in the spring 2018 semester. The librarians added showing students how to find

the formatted citations in databases, and if that was not available, how to

find the citation in Google Scholar. For help beyond that, librarians reminded

students that the Writing Center was available. Consultations for each team

continued to be scheduled for one hour.

For the fall 2018 semester, the consultation was

shortened from one hour to 30 minutes. During the first week of the semester,

the second author met with each class section and provided an overview of the

course guide, the new tutorials, and the assignment. Thus, prior to the

consultation, librarians told the teams via email to review the tutorials so

that they could be better prepared for the session. Librarians used the team

process interview questions to help guide the consultation.

Practical Implications

Our project illuminated multiple considerations for

assessing consultations. First, framing questions on the one-minute papers

positively elicited more responses than negatively framed questions.

Descriptions of how to use one-minute papers advise asking a question about

points of confusion, the muddiest point, or what is unclear (Bowles-Terry &

Kvenild, 2015; Schilling & Applegate, 2012).

While several versions of our one-minute papers had this type of question, we

found that framing the question positively provided us with more actionable

data. For example, instead of “What question remains unanswered?” we asked,

“What would you like to learn more about?” This finding supports Bowles-Terry

and Kvenild’s (2015) caution about using a negatively

framed assessment technique too often.

Also, librarians should consider the possible role that

each assessment method could play in student learning (Oakleaf, 2009).

Reflection is part of the learning process (Fosnot & Perry, 1996). Offering

a one-minute paper at the end of the consultation provided students time to

reflect on the session and could potentially deepen learning. The questions

asked during the team process interviews also helped students frame their

learning and what was needed next for their assignment. The questionnaire

allowed students to reflect on what information sources they used throughout the

semester. However, the retrospective interviews, while reflective, were more

informative for the librarian than the students.

Limitations

Our study has several limitations. First, the involvement

of stakeholders is key to action research. While we involved stakeholders in

our project, stakeholder involvement in assessment design, data collection, and

data analysis could be expanded. In particular, we could look for ways to

include students. Second, only one person coded all of the data. Although we

frequently discussed the findings during the coding process, having only one person code the data could have led to bias. Finally,

all of the data collected represent individual student perceptions. For our

project, we did not feel the student perceptions were a large limitation, as we

were able to see that students’ reports of learning mapped to the consultation

learning outcomes. However, future assessments could use other methods like

journaling, pre/post testing, and citation analysis of the project.

Conclusion

We used action research to evaluate four assessment

methods for consultations. The action research method allowed us to plan an

assessment, implement the assessment, analyze the results, reflect on the

effectiveness and utility of the assessment, and make changes to the assessment

for the next semester. The cyclical nature of this project allowed us to make

changes and continuously reflect on the usefulness of each method. After

implementing one-minute papers, team process interviews, questionnaires, and

retrospective interviews, we found that questionnaires were the best assessment

method for our context. Questionnaires provided the most actionable information

about both the effectiveness of the instruction and the logistics of the

consultation and were the easiest to administer. The continuous evaluation and

modification of an assessment method allows for the development of an

assessment that is the best for a particular context.

Acknowledgements

Thank you to T. Derek Halling,

David Hubbard, Mike Larson, Bruce Neville, Chad Pearson, Ashley Staff, Jane

Stephens, and Gary Wan for assistance with data collection. Thank you to

Michael R. Golla for his support of our research

project.

References

Bowles-Terry, M., & Kvenild, C. (2015). Classroom

assessment techniques for librarians. Chicago, IL: Association of College

and Research Libraries.

Brown-Sica,

M. (2012). Library spaces for urban, diverse commuter students: A participatory

action research project. College &

Research Libraries, 73(3), 217-231.

https://doi.org/10.5860/crl-221

Brown‐Sica, M., Sobel, K., & Rogers, E.

(2010). Participatory action research in learning commons design planning. New Library World, 111(7/8), 302-319. https://doi.org/10.1108/03074801011059939

Butler, K., & Byrd, J.

(2016). Research consultation assessment: Perceptions of students and

librarians. The Journal of Academic

Librarianship, 42(1), 83–86. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2015.10.011

Coghlan, D. &

Brydon-Miller, M. (2014). Introduction. In The SAGE encyclopedia of action research. London :

SAGE. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781446294406

Cox, A., Gruber, A. M., &

Neuhaus, C. (2019). Complexities of demonstrating library value: An exploratory

study of research consultations. portal:

Libraries and the Academy, 19(4),

577-590. https://doi.org/10.1353/pla.2019.0036

Creswell, J. & Guetterman, T. (2019). Educational

research: Planning, conducting, and evaluating quantitative and qualitative

research (6th ed.). New York, NY: Pearson.

Drew, C., & Vaz, R. (2008, June). Global

projects preparation: Infusing information literacy into project

based curricula [Paper presentation]. 2008 Annual Conference &

Exposition, Pittsburgh, PA, United States. https://peer.asee.org/3738

Faix, A., MacDonald, A., & Taxakis,

B. (2014). Research consultation effectiveness for freshman and senior

undergraduate students. Reference

Services Review, 42(1), 4-15. https://doi.org/10.1108/RSR-05-2013-0024

Fosnot, C. T., & Perry, R. S. (1996). Constructivism: A psychological

theory of learning. In C. T. Fosnot (Ed.), Constructivism:

Theory, perspectives, and practice (pp. 8-38). New York: Teachers College

Press.

Fournier, K., & Sikora, L.

(2015). Individualized research consultations in academic libraries: A scoping

review of practice and evaluation methods. Evidence

Based Library and Information Practice, 10(4),

247-267. https://doi.org/10.18438/B8ZC7W

Fournier, K., & Sikora, L.

(2017). How Canadian librarians practice and assess

individualized research consultations in academic libraries: A nationwide

survey. Performance Measurement and

Metrics, 18(2), 148-157. https://doi.org/10.1108/PMM-05-2017-0022

Goek, S. (2019). Sign up now for Project Outcome for Academic

Libraries. Retrieved from https://www.acrl.ala.org/acrlinsider/archives/17406

Hanlan, L. R., & Riley, E. M. (2015, June). Information use by undergraduate STEM teams

engaged in global project-based learning [Paper presentation]. 2015 ASEE

Annual Conference & Exposition, Seattle, WA, United States. https://doi.org/10.18260/p.24300

Insua, G. M., Lantz, C., & Armstrong, A. (2018). In their

own words: Using first-year student research journals to guide information

literacy instruction. portal: Libraries

and the Academy, 18(1), 141-161. https://doi.org/10.1353/pla.2018.0007.

Kemmis, S., McTaggart, R., & Nixon, R. (2014). The action research planner: Doing critical

participatory action research. New York: Springer.

https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-4560-67-2

Kong, N., Fosmire, M., & Branch, B. D.

(2017). Developing library GIS services for humanities and social science: An

action research approach. College &

Research Libraries, 78(4),

413-427. https://doi.org/10.5860/crl.78.4.413

LeMire, S., Sullivan, T. D., & Kotinek,

J. (2019). Embracing the spiral: An action research assessment of a

library-honors first year collaboration. The

Journal of Academic Librarianship, 45(5), 102042. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2019.05.010

Magi, T. J., & Mardeusz, P. E. (2013). Why some students continue to value

individual, face-to-face research consultations in a technology-rich world. College & Research Libraries, 74(6), 605-618. https://doi.org/10.5860/crl12-363

Malenfant, K., Hinchliffe, L., & Gilchrist, D. (2016).

Assessment as action research: Bridging academic scholarship and everyday

practice. College & Research

Libraries, 77(2), 140-143. https://doi.org/10.5860/crl.77.2.140

Margolin, S., Brown, M., &

Ward, S. (2018) Comics, questions, action! Engaging students and instruction

librarians with the Comics-Questions Curriculum. Journal of Information Literacy, 12(2), 60-75.

https://doi.org/10.11645/12.2.2467

Melgoza, P. (2017, June). Mentoring

industrial distribution students on their junior and senior papers [Paper

presentation]. 2017 ASEE Annual Conference & Exposition, Columbus, OH,

United States. https://peer.asee.org/28663

Miller, R. E. (2018). Reference consultations and student success outcomes.

Reference & User Services Quarterly,

58(1), 16-21. https://doi.org/10.5860/rusq.58.1.6836

Morgan, D. L. (2019). Basic and advanced focus groups. Thousand

Oaks, CA: SAGE.

Newton, L. & Feinberg, D.

E. (2020). Assisting, instructing, assessing: 21st century student centered

librarianship. The Reference Librarian,

61(1), 25-41. https://doi.org/10.1080/02763877.2019.1653244

Oakleaf, M. (2009). The

information literacy instruction assessment cycle: A guide for increasing

student learning and improving librarian instructional skills. Journal of Documentation, 65(4), 539-560. https://doi.org/10.1108/00220410910970249

Reason, P. & Bradbury, H.

(Eds.). (2006). Handbook of action

research: The concise paperback edition. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

Reinsfelder, T. L. (2012). Citation analysis as a tool to measure

the impact of individual research consultations. College & Research Libraries, 73(3), 263-277. https://doi.org/10.5860/crl-261

Rogers, E. & Carrier, H. S.

(2017). A qualitative investigation of patrons’ experiences with academic

library research consultations. Reference

Services Review, 45(1), 18-37.

https://doi.org/10.1108/RSR-04-2016-0029

Savage, D. (2015). Not counting

what counts: The perplexing inattention to research consultations in library

assessment activities. In D. M. Mueller (Ed.), Creating Sustainable Community: The Proceedings of the ACRL 2015

Conference, March 25–28, Portland, Oregon (pp. 577-584). Chicago:

Association of College and Research Libraries. Retrieved from http://www.ala.org/acrl/sites/ala.org.acrl/files/content/conferences/confsandpreconfs/2015/Savage.pdf

Schilling, K., & Applegate,

R. (2012). Best methods for evaluating educational impact: A comparison of the

efficacy of commonly used measures of library instruction. Journal of the Medical Library Association: JMLA, 100(4), 258-269. https://doi.org/10.3163/1536-5050.100.4.007

Sikora, L., Fournier, K., &

Rebner, J. (2019). Exploring the impact of

individualized research consultations using pre and posttesting

in an academic library: A mixed methods study. Evidence Based Library & Information Practice, 14(1), 2–21.

https://doi.org/10.18438/eblip29500

Sokoloff, J., & Simmons, R.

(2015). Evaluating citation analysis as a measurement of business librarian

consultation impact. Journal of Business

& Finance Librarianship, 20(3),

159-171. https://doi.org/10.1080/08963568.2015.1046783

Stephens, J., Melgoza, P., Hubbard, D.E.,

Pearson, C.J., & Wan, G. (2018). Embedded information literacy instruction

for upper level engineering undergraduates in an intensive writing course. Science & Technology Libraries, 37(4), 377-393. https://doi.org/10.1080/0194262X.2018.1484317

Suskie, L. (2018). Assessing student learning: A common sense

guide (3rd ed.). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Watts, J., & Mahfood, S. (2015).

Collaborating with faculty to assess research consultations for graduate

students. Behavioral & Social

Sciences Librarian, 34(2), 70-87. https://doi.org/10.1080/01639269.2015.1042819

Woodland, R. H. (2018). Action

Research. In B. Frey (Ed.), The SAGE

encyclopedia of educational research, measurement, and evaluation (pp.

37-38). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781506326139.n18

Yee, S., Arnold, J., Rankin,

J., Charbonneau, D., Beavers, P., Bielat, V., Krolikowski, Oldfield, M., Phillips, S., & Wurm, J. (2018). Assessment in Action Wayne State

University. Retrieved from https://guides.lib.wayne.edu/aiawaynestate

Appendix A

Team Process

Interview Protocol

1. What did you turn in for the project?

2. Are you satisfied with your project report submittal?

Did you have sufficient information to submit for the update?

3. Is there anything that you wish you had done

differently?

4. What do you need to submit for your next project due

date?

5. What kind of information do you need for the next due

date?

Appendix B

Questionnaire

Instruments

Fall 2017

Met with a Librarian

|

Version

|

Questions

|

|

1

|

1. What was helpful?

2. What was not helpful?

|

|

2

|

1. What was the most important thing you learned during

this consultation?

2. Do you need help with citing resources in your

project? Which citation style did you use?

|

Did Not Meet with a Librarian

|

Version

|

Questions

|

|

1

|

1. Were there any barriers to meeting with the

librarian for the research consultation?

2. Did you use the Library IDIS Class Guide? Which

sections?

|

|

2

|

1. Did you find or use any resources that the Library

should add to their IDIS 303 Class Guide or book collection?

2. Do you need help with citing resources in your

project? Which citation style did you use?

|

Spring 2018

Met with Librarian

1. What was the most important thing you learned during

the consultation?

2. What did you learn about library resources that you

could use in your future courses?

3. Do you intend to schedule an appointment with a

librarian in MMET 401 (currently IDIS 403)? Why?

4. Librarians currently meet with one team at a time. For

the future MMET 301 (currently IDIS 303) team meetings, we are considering

having multiple teams meet with a librarian at the same time and providing

information using video tutorials.

a. What aspects of the one-on-one team meeting were most

beneficial to you?

b. Based on your research consultation experience, do you

have any concerns about multiple teams meeting with a librarian at once?

c. What information from the research consultation would

you like see in video tutorial format?

Did Not Meet with Librarian

1. Did anyone on your team meet with a librarian?

2. If someone from your team met with a librarian, what

did they share with you about finding information for your team’s project?

3. How did your team choose a topic?

4. Where did you find the information needed to write

your paper?

5. How did you find the information needed to write your

paper?

6. Did you know the library created an IDIS 303 class

guide to assist you with finding sources for your paper?

Fall 2018

Met with a Librarian

1. What was the most important thing you learned during

the consultation?

2. What did you learn about library resources and

services that you could use in your future courses?

3. Librarians currently meet with one team at a time, but

have considered meeting with multiple teams at once. What aspects of the

one-on-one team meeting were most beneficial to you?

4. What are your impressions about the 30-minute length

of the consultation?

5. Did you meet with a librarian multiple

times? Why or why not?

6. Do you wish you had met with an engineering librarian

before this class? If so, in which course or context?

7. Do you intend to schedule an appointment with a

librarian in MMET 401? Why or why not?

8. Did you view any of the library tutorial videos?

9. What information from the research consultation would

you like to see in video tutorial format?

Did Not Meet with a Librarian

1. Did anyone on your team meet with a librarian?

2. If someone from your team met with a librarian, what

did they share with you about finding information for your team’s project?

3. Do you intend to schedule an appointment with a

librarian in MMET 401? Why or why not?

4. Did you know the library created an online MMET 301

class guide to assist you with finding sources for your paper?

5. How did your team choose a topic?

6. How did you find the information needed to write your

paper?

7. Did you have any difficulty finding the information

for your paper? Please describe.

8. Did you view any of the library tutorial videos?

9. What information from the research consultation would

you like to see in video tutorial format?

Appendix C

Retrospective

Interview Protocol

1. What did you enjoy about the class project?

2. What did you not enjoy about the class project?

3. How did the information that you needed early in the

assignment compare to the information that you needed closer to the assignment

due date?

4. Think about how the research consultation fit within

the flow of your research assignment. How would you describe the timing of your

consultation: too early, just right, too late? Why?

5. How did you approach finding resources for your paper

after meeting with a librarian?

6. Describe the resources that you used to find

information for your project.

7. Did you use any sources that were not mentioned by a

librarian?

8. Did you use the library’s Get It for Me service to obtain any resources?

9. How did you decide which sources to use and which not

to use?

10. What could have made the research consultation

experience better?

11. Consider you are talking to

a student who will be taking the IDIS 303 or IDIS 403 course next semester.

What would you say about meeting with a librarian to that student?

12. Is there anything else you would like to add about

the research consultations?

![]() 2020 Kogut and Melgoza. This is an Open

Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

2020 Kogut and Melgoza. This is an Open

Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.