Review Article

Twenty Years of Business Information Literacy Research: A

Scoping Review

Meggan A.

Houlihan

College Liaisons Coordinator

for Social Sciences, Humanities, Arts, and Business

Morgan Library

Colorado State University

Fort Collins, Colorado, United

States of America

Email: meggan.houlihan@colostate.edu

Amanda B. Click

Head of Research &

Instruction

Nimitz Library

United States Naval Academy

Annapolis, Maryland, United

States of America

Email: click@usna.edu

Claire Walker Wiley

Research & Instruction

Librarian

Lila D. Bunch Library

Belmont University

Nashville, Tennessee, United

States of America

Email: claire.wiley@belmont.edu

Received: 27 Feb. 2019 Accepted: 17 Aug. 2020

![]() 2020 Houlihan, Click, and Wiley. This is an Open

Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

2020 Houlihan, Click, and Wiley. This is an Open

Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

DOI: 10.18438/eblip29745

Abstract

Objective – This study analyzes and synthesizes the business

information literacy (BIL) literature, with a focus on trends in publication

type, study design, research topic, and recommendations for practice.

Methods – The scoping

review method was used to build a dataset of 135 journal articles and

conference papers. The following databases were searched for relevant

literature published between 2000 and 2019: Library and Information Science

Source, Science Direct, ProQuest Central, Project Muse, and the Ticker journal site. Included items were

published in peer reviewed journals or conference proceedings and focused on

academic libraries. Items about public or school libraries were excluded, as

were items published in trade publications. A cited reference search was conducted

for each publication in the review dataset.

Results – Surveys were, by

far, the most common research method in the BIL literature. Themes related to

collaboration were prevalent, and a large number of publications had multiple

authors or were about collaborative efforts to teach BIL. Many of the

recommendations for practice from the literature were related to collaboration

as well; recommendations related to teaching methods and strategies were also

common. Adoption of the Framework for

Information Literacy for Higher Education in BIL appears slow, and the

citations have decreased steadily since 2016. The majority of the most

impactful BIL articles, as measured by citation counts, presented original

research.

Conclusions – This study

synthesizes two decades of literature and contributes to the evidence

based library and information science literature. The findings of this

scoping review illustrate the importance of collaboration, interest in teaching

methods and strategies, appreciation for practical application literature, and

hesitation about the Framework.

Introduction

Business librarians face unique challenges in the

classroom. From faculty partner expectations to the diverse research skills

required, this group must think creatively in order to achieve learning

outcomes and demonstrate the value of information literacy (IL) on their

campuses. This study, which is focused on the intersection of information

literacy and the discipline of business, is important because business is the

most popular undergraduate degree in the U.S. and has been for decades

(National Center for Education Statistics, 2017). Business librarians can have

a great impact on this large group of students with innovative and effective

approaches to information literacy. This study uses the scoping review method

in order to explore innovations and approaches to information literacy in

business.

Two foundational documents from the Association of

College & Research Libraries (ACRL) have guided information literacy

practice over the last 20 years: The Information

Literacy Competency Standards for Higher Education (2000) and the Framework for Information Literacy for

Higher Education (2015). The Standards

and Framework are built on the same

principles, but the theory behind them and the implications for practice are

quite different. The Standards

include information literacy competencies and performance indicators, while the Framework includes knowledge practices

and dispositions that can be harder to assess. The definition of information

literacy has also evolved, and this change is reflected in the Framework document. This shift reflects

a change in thinking in library and information science, but it has been met

with some resistance. Survey results published in 2005 and 2018 demonstrate

that business librarians have struggled with integrating them into their

teaching practice for a number of reasons. In Cooney’s (2005) survey of

business librarians, only a third of survey respondents reported incorporating

the Standards into their instruction,

and assessments of student learning in this area were rarely conducted. Cooney

also discovered that business information literacy (BIL) instruction was still

developing and that there was great room for improvement in collaboration

between librarians and business faculty. Guth and

Sachs (2018) recreated Cooney’s survey by exploring implementation of both the Standards and the newer Framework and discovered several

interesting points of comparison with the 2005 responses. Most notably, both

the average number of information literacy sessions taught annually and the

number of librarians with business as part of their job title decreased.

Responses showed an increase in the use of online tutorials for BIL efforts. Guth and Sachs also found that more than half (58%) of

their survey respondents had incorporated or were in the process of

incorporating the Standards in 2015,

which is a notable increase from Cooney’s survey in 2005. However, 39% of the

2015 respondents had incorporated the Framework

into their IL efforts.

These surveys provide valuable information on how

business librarians are approaching information literacy, but these responses

also prompt additional questions that may be answered through a scoping review

of the literature. Examining the evidence available in the literature can

provide deeper insight into these topics and serve as complementary evidence to

inform the future direction of BIL.

This study utilizes the scoping review method in order to

explore the following research question: How can the business information

literacy literature be characterized regarding publication type, study design,

findings, impact, and recommendations for practice? This scoping review aims to

add to the evidence based literature in library and information science (LIS),

report on the current state of BIL, and provide business librarians with

insight that can be used to improve future information literacy efforts.

Scoping reviews are best used when the researcher wants

to examine the nature of research activity in a particular field, summarize and

disseminate findings, or identify gaps in the literature (Arksey &

O’Malley, 2005). Thus far, this method is not common in the LIS discipline,

aside from the health and medical librarianship subfield. It has, however, been

used to explore mentoring programs for academic librarians (Lorenzetti & Powelson, 2015), implementation of Web 2.0 services (Gardois, Colombi, Grillo, & Villanacci, 2012), individualized research consultations

(Fournier & Sikora, 2015), researchers’ use of social network sites (Kjellberg, Haider, & Sundin,

2016), and generational differences in library leadership (Heyns,

Eldermire, & Howard, 2019).

This method aims to “map the literature on a particular

topic or research area and provide an opportunity to identify key concepts;

gaps in the research; and types and sources of evidence to inform practice,

policymaking, and research” (Daudt, van Mossel, &

Scott, 2013, p. 8). They differ from systematic reviews in a number of ways.

Scoping reviews may be designed around broader research questions. Research

quality may not be an initial priority. These studies may or may not include

data extraction, and synthesis tends to be more qualitative (Brien, Lorenzetti,

Lewis, Kennedy, & Ghali, 2010). Arksey and

O’Malley (2005) identify the following stages in their scoping study framework:

- Identify the

research question(s)

- Identify

relevant studies

- Select the

studies

- Chart the data

- Collate,

summarize, and report the results

The following sections describe each of these scoping

review steps in the context of this study as well as an additional step we took

in completing the review.

Identify the

Research Question

This study was designed to analyze the BIL literature in

order to identify trends in authorship, method, theory, research topic,

findings, impact, and recommendations for practice.

In order to identify the databases to be searched, we

used a list of the top 25 LIS journals (Nisonger

& Davis, 2005) and added two business librarianship-specific titles: Journal of Business and Finance

Librarianship and Ticker: The

Academic Business Librarianship Review. We then identified the databases in

which these 27 journals are indexed and conducted systematic searches. We

searched the following databases for relevant literature published between

January 2000 and December 2019: Library and Information Science Source, Science

Direct, ProQuest Central, Project Muse, and the Ticker journal site. We searched for articles with “information

literacy” and business or economics in the following fields: title, abstract,

subject terms, and author-supplied keywords. We utilized database thesauri, when

possible, as well as keyword searching.

Items were included in the review if they were published

in peer reviewed journals or conference proceedings and focused on academic

libraries. Items about public or school libraries were excluded, as were items

published in trade publications.

The LIS literature tends to include a great deal of

articles that simply describe practice. For example, the publication might

describe a teaching method, newly developed learning object, or outreach

effort. This type of literature, which we have classified as “practical

applications,” may inform the practice of other librarians and thus was

included in the scoping review. The goal of the study was to identify

publication trends not to exclude non-rigorous work.

The publication dataset was divided into three sections,

and two of the three researchers coded each third. Coding disagreements were

settled by the third researcher. Each publication was coded for publication

title and type, document type, authorship and collaboration, study population,

research methods, theories and models, topics, key findings, and

recommendations. The dataset was stored in a spreadsheet that included document

citations and fields for every item in Table 1, with the exception of key

findings and recommendations. Qualitative data analysis software NVivo version

12 was used to code the publications, including key finding and recommendation

text. Some codes were selected prior to coding, but others emerged from the

data throughout the coding process. The same 30 codes were used for topic, key

findings, and recommendations, a list of which can be found in Appendix A.

Models and theories were coded for each publication only

if they informed the study design or interpretation of the findings. Merely

mentioning a theory or model in a literature review without specific

application was not enough to warrant coding. Thirty research topics were used

to code every publication, and each publication was assigned up to three topic

codes.

Collate and

Summarize the Results

The dataset was analyzed to identify trends in topics,

research populations, methods, and more. Findings and recommendations that

could inform the BIL instruction practice of academic librarians were of

particular interest.

Table 1

Publication Feature Types and

Items

|

Feature Type |

Item |

|

Publication |

Category (e.g., journal article, conference paper) |

|

|

Date of publication |

|

|

Research classification (e.g., original research,

literature review) |

|

Study Design |

Theory or model (e.g., grounded theory, technology

acceptance model) |

|

|

Methods (e.g., interviews, surveys) |

|

|

Population (e.g., undergraduate business students,

librarians) |

|

Content |

Topics (e.g., assessment, information-seeking behavior,

workplace information literacy) |

|

|

Key findings |

|

|

Recommendations |

Figure 1

PRISMA flow diagram for BIL

scoping review.

Cited Reference Search

In order to explore

the impact of the publications included in the scoping review, we conducted a

cited reference search. We searched for each publication in Google Scholar and

recorded the number of times each had been cited. Note that this part was an addition

to the study design and not a step in the scoping review method.

Results

The original searches outlined in the methods identified

more than 1,200 articles, but after removing duplicates and out-of-scope

articles, the final dataset included 135 publications. These 135 publications

met the criteria for inclusion and were further analyzed. Figure 1 provides

more detail on the publication selection process in the form of a PRISMA Flow

Diagram. See Appendix B for the list of all included publications.

Publication Categories

Of these 135 included publications, 132 (98%) were

published in peer reviewed journals. Although, it is important to note that not

all of these articles presented original research, despite their peer reviewed

status. Forty-two different journal titles and two conference proceedings were

represented. Only four journals published five or more articles that met the

study criteria, including The Journal of Academic Librarianship (5

articles), Journal of Information

Literacy (8 articles), Reference

Services Review (15 articles), and Journal

of Business & Finance Librarianship (49 articles). Three papers

published in conference proceedings met the study criteria and were included.

Two papers were published in Procedia -

Social and Behavioral Sciences and one in Qualitative & Quantitative Research Methods in Libraries. A

list of all titles can be found in Appendix

C.

Date of Publication

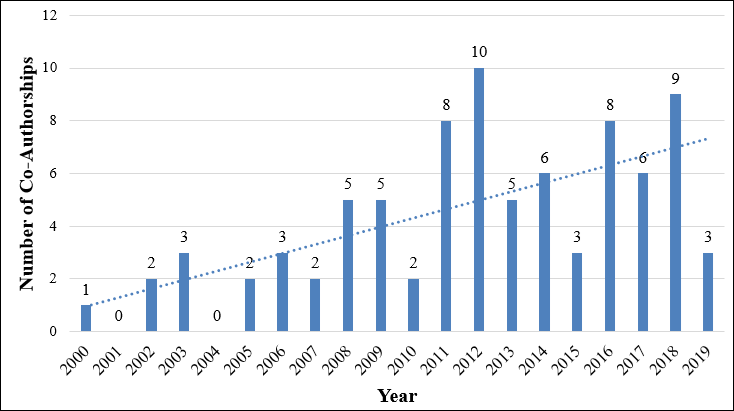

As demonstrated in Figure 2, there has been a continued

but irregular growth in the number of BIL publications per year between January

2000 and December 2019. The average number of publications per year is 6.75,

and publications on the topic peaked in 2012 and 2016, with fifteen

publications each year.

Research Classification

Of the 135 publications included in the study, 85 were

identified as research articles (63%), 37 as “practical applications”

publications (27%), nine as think pieces (7%), and four literature reviews

(3%). Any publication with a methods section was considered to be original research,

although exceptions were made for non-U.S. publications that used alternative

research paper terminology or format. If a methods section was clearly present

but not labeled as such, it was included in the dataset. “Practical

applications” publications typically described a successful lesson plan,

collaboration, or learning activity implemented by a library. Think pieces are

publications that usually include an extensive review of the literature but

also the author’s analysis of or opinion on the topic. Figure 3 shows the

number of each document type published by year.

Publications were coded for study population if

appropriate, including populations like undergraduate business students and

business faculty. Populations were identified in three publication types:

original research, practical applications, and think pieces. For example, a

practical applications publication might describe a new BIL initiative that

focused specifically on MBA students, and so it would be coded with a population

even though it was not a research study. Sixty-one percent of the publications

in the dataset studied undergraduate business students. Some specified

subgroups, such as first-year business students (14 publications),

undergraduate marketing students (six publications), and undergraduate

management students (six publications). Twenty-six articles focused on master’s

level graduate business students, and 15 of these 26 studied MBA students

specifically. Of the 85 original research articles, 68% studied undergraduate

business students and 20% studied graduate business students. The most common

populations are listed in Table 2. All population types outside of these four

(e.g., corporate librarians, PhD business students) appeared fewer than five

times.

Figure 2

BIL publications per year, 2000–2019.

Figure 3

Document type by year,

2000–2019.

Table 2

Study Populations with Total

Number and Percentages of Appearances

|

Study Populations |

Total Number of Publications |

Percentage of Publications |

|

Undergraduate business

students |

83 |

61% |

|

Graduate business students

(master’s level) |

26 |

19% |

|

Business faculty |

8 |

6% |

|

Business librarians |

5 |

4% |

A total of 263 authors from various disciplines and

positions are represented in the study. Author position (e.g., business

librarian, LIS faculty) was not always clear. Authors were only coded when

positions were specified in the article or in the database record, resulting in

some authors being coded as unknown. Fifty-two publications were published by a

single author, and 83 publications were collaboratively authored. The most

common type of collaboration involved librarian co-authorships (26) followed by

at least one librarian and one business faculty member (25). Interestingly,

seven publications were authored solely by business faculty collaborations that

did not include librarians. There was a steady increase in co-authored

publications between 2000 and 2019 (see Figure 4).

Eighty-five

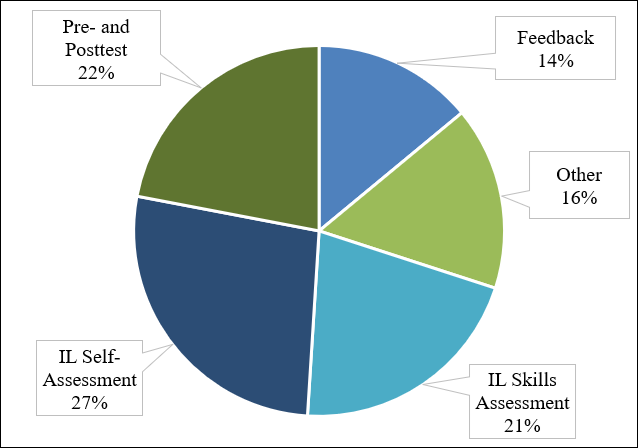

publications used a research method to gather information related to BIL.

Within this dataset, eight unique research methods were applied. Surveys were

by far the most common method, used in 72% of the original research

publications. Many studies used multiple types of surveys, and in fact there

were five different survey types: IL self-assessment, pre- and posttest, IL

skills assessment, feedback, and other. Distinctions between the categories

were as follows: IL self-assessment surveys gauged student perceptions of their

individual IL skill levels (e.g., How comfortable are you identifying peer

reviewed sources?). Pre- and posttest surveys were distributed both before and

after an instruction session or IL intervention. IL skills surveys focused on

assessing IL skill level (e.g., Please identify the Boolean operators in the

following search statement.). Feedback surveys requested input on a learning

object or activity such as a research guide or lesson plan. The other survey

category covered any survey that did not fit into those listed above. See

Figure 5 for more detail about the multiple types of surveys. Additional

methods included content analysis, interviews, case studies, and focus groups.

Nineteen publications utilized more than one research method, and 66

publications relied on one method only. The most popular research methods and

the frequency of each can be found in Table 3; all other methods appeared fewer

than five times.

Figure 4

Number of publications with

multiple authors by year, 2000–2019.

Table 3

Most Popular Research Methods with

Number and Percentage of Publications in Which They Appeared

|

Research Method |

Total Number of

Publications |

Percentage of Publications |

|

Survey |

61 |

72% |

|

Content analysis |

17 |

13% |

|

Interviews |

12 |

10% |

|

Case study |

10 |

7% |

Figure 5

Percentages of surveys by

type.

Only

15 of the 135 (11%) publications indicated use of a theory or model in

informing their study design, and seven of those publications used more than

one. Only three models or theories appeared more than once, Bloom’s taxonomy

(Jefferson, 2017; Nentl & Zietlow,

2008), adult learning theory (An & Quail, 2018; Quinn & Leligdon, 2014), and the Seven Pillars of Information

Literacy (McKinney & Sen, 2012; Webber & Johnson, 2000).

The

top six codes applied were collaboration

and

faculty partnerships, teaching methods and strategies, assessment, IL skills,

information-seeking behavior, and online tutorials. The top ten topics can be

seen in Table 4. All other codes appeared nine or fewer times. See Appendix A

for the topics codebook.

Key Findings and

Recommendations

Key findings were coded for original research articles.

The top five key findings were related to IL skills, instruction impact,

student perceptions, information-seeking behavior, and online resources. The

top ten key findings topics can be seen in Table 5. Some publications warranted

the use of multiple codes related to the same idea. For example, “instruction

impact” was used in conjunction with an additional code such as “evaluation of

information” in order to reflect that 1) learning was self-reported and 2)

learning was related to information evaluation. In a 2012 article, Finley and Waymire found that students self-reported an increased

comfort level with “evaluating the credibility, accuracy, and validity of

sources” (p. 34) after receiving IL instruction. Regarding the nesting of

codes, evaluation of information is an IL skill and thus might be considered

part of that topic. However, publications are often focused on this specific skill,

more so than other IL skills. Evaluation of information clearly emerged from

the data as its own code.

Fewer than half of the publications offered specific

recommendations. The recommendations that did appear were most frequently

related to collaboration/faculty partnerships, teaching methods/strategies, and

assessment.

Table 4

Most Popular Research Topics with

Number and Percentage of Publications in Which They Appeared

|

Research Topic |

Number of

Publications |

Percentage of

Publications |

|

Collaboration and faculty partnerships |

47 |

35% |

|

Teaching methods and strategies |

46 |

34% |

|

Assessment |

42 |

31% |

|

IL Skills |

20 |

15% |

|

Information-seeking behavior |

15 |

11% |

|

Online tutorials |

15 |

11% |

|

One-shot sessions |

14 |

10% |

|

Instruction impact |

13 |

10% |

|

Student perceptions |

12 |

9% |

|

Workplace IL |

12 |

9% |

Cited IL Standards

and Frameworks

This

body of literature cited a variety of IL standards and frameworks, including

the Australia and New Zealand Information Literacy Framework (ANZIL),

Association to Advance Collegiate Schools of Business (AASCB) Accreditation Standards, Society of

College, National and University Libraries (SCONUL) Seven Pillars of Information Literacy, Association of College &

Research Libraries (ACRL) Information

Literacy Competency Standards for Higher Education, ACRL Framework for Information Literacy for

Higher Education, and BRASS’s Business

Research Competencies. Overall, the following standards were cited most

often: ACRL Standards (59

references), AASCB Standards (24

references), and ACRL Framework (16

references). Figure 6 illustrates the number of citations per year for each of

these. Twenty-five publications cited more than one standard or framework. The Business Research Competencies developed

by BRASS, the Business Reference and Services Section within RUSA (Reference

& User Services Association), were cited only twice.

In order to better understand the impact of the BIL

literature, a cited reference search was conducted in Google Scholar for all

135 publications. Table 6 lists the top ten most highly cited publications from

the dataset. There are, of course, numerous ways to measure the impact of a

publication, but for the purposes of this study citations were chosen to

illustrate the impact snapshot. In addition, it is important to note that some

of the publications in the dataset were published recently and thus have not

yet been cited frequently.

Table 5

Most Popular Key Findings

Topics with Number and Percentage of Publications in Which They Appeared,

Examples from the Publications, and Topic Definitions

|

Key Finding

Topics and Definitions |

Number of

Publications |

Percentage of

Publications |

Example From Publications |

|

IL skills: Assessment or perception of the ability to evaluate,

locate, or use information ethically |

28 |

21% |

“Generally speaking, librarians, library

administrators, and faculty believe that students are lacking the necessary

information literacy skills. This stands in contrast to the perceptions of

many students, who tend to see their skills as well developed or adequate for

completing school assignments” (Detlor, Julien, Willson, Serenko, &

Lavallee, 2011, p. 583). |

|

Instruction

impact: Participant self-reported change in learning or

understanding due to IL instruction or learning object |

23 |

17% |

“Based on the quiz performance, it seems that the

instructional videos did prepare students for the library instruction session

by teaching basic business research concepts” (Camacho, 2018, p. 33). |

|

Student

perceptions: Participant self-reported

learning or understanding of the library, librarian, or resources |

16 |

12% |

“The feedback…indicated that this group of first year

[business] students were comfortable with the prospect of undertaking library

research and expected to be able to meet course research expectations” (Matesic & Adams, 2008, p. 7). |

|

Evaluation of

information: Assessment of or

self-reported information evaluation skills and/or behaviors |

13 |

10% |

“Prior studies have suggested that some employees do

not always evaluate information . . . but this study found that 82% of all

jobs mentioned evaluation skills” (Gilbert, 2017, p. 127). |

|

Information-seeking

behavior: Behaviors related to finding needed information in- and

outside of the library setting |

13 |

10% |

“The results also confirmed the authors’ suspicions

that students largely rely on web-based search engines, like Google, to

conduct their research” (Bryant & Hooper, 2017, p. 411). |

|

Online resources:

Feedback on or reported use of online resources such as

a database, website, or research guide |

12 |

9% |

“Research analysis found a range of attitudes toward

the use of Wikipedia in higher education, with all interviewees expressing a

level of caution regarding its use” (Bayliss, 2013, p. 49). |

|

Workplace IL: Needed or used IL skills in the workplace setting |

12 |

9% |

“The university students who performed better on a

commercial assessment of information literacy produced better emails, memos,

and technical reports as reflected in their grade in a business

communications course” (Katz, Haras, & Blaszczynski, 2010, p. 146). |

|

Assessment: Measured student learning through a pre- and posttest

or similar method |

12 |

9% |

“Across all four categories of knowledge including

library usage experience, post-instruction session averages are significantly

higher than pre-instruction session” (Gong & Loomis, 2009). |

|

Collaboration,

and faculty partnerships: Identified collaboration within the library or institution

in IL efforts |

10 |

7% |

“We found that successfully implementing the

integration of IL skills into the business curriculum was contingent upon the

level of continuous institutional support and faculty commitment to the

process” (Rodríguez, Cádiz, & Penkova, 2018, p.

127). |

|

Teaching methods

and strategies: Reported use of a specific

teaching method or strategy used for IL efforts |

9 |

7% |

“This study confirms the findings from the library

science literature that a research guide is effective when targeted to a

class as a course page and there is concurrent instruction on how to use the

page by the librarian” (Leighton & May, 2013, p. 135). |

Figure 6

Number of publications citing

the ACRL Standards, ACRL Framework, and AACSB Standards by

year, 2000–2019.

Table 6

Ten Most Highly Cited

Publications in this Study with Citation Count

|

Number of Times Cited in Google Scholar |

Full Citation |

|

490 |

Johnston, B., & Webber, S. (2003). Information

literacy in higher education: A review and case study. Studies in Higher Education, 28(3), 335–352. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075070309295 |

|

482 |

Webber, S., & Johnston, B. (2000). Conceptions of

information literacy: New perspectives and implications. Journal of Information Science, 26(6), 381–397. https://doi.org/10.1177/016555150002600602 |

|

203 |

Williams, J., & Chinn, S. J. (2009). Using Web 2.0

to support the active learning experience. Journal of Information Systems Education, 20(2), 165–174.

Available at http://jise.org/volume20/n2/JISEv20n2p165.html |

|

159 |

O’Sullivan, C. (2002). Is information literacy relevant

in the real world? Reference Services

Review, 30(1), 7–14. https://doi.org/10.1108/00907320210416492 |

|

100 |

Fiegen, A. M.,

Cherry, B., & Watson, K. (2002). Reflections on collaboration: Learning

outcomes and information literacy assessment in the business curriculum. Reference Services Review, 30(4),

307–318. https://doi.org/10.1108/00907320210451295 |

|

91 |

Donaldson, K. A. (2000). Library research success:

Designing an online tutorial to teach information literacy skills to

first-year students. The Internet and

Higher Education, 2(4), 237–251. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1096-7516(00)00025-7 |

|

87 |

Lombardo, S. V., & Miree,

C. E. (2003). Caught in the web: The impact of library instruction on

business students' perceptions and use of print and online resources. College & Research Libraries, 64(1),

6–22. https://doi.org/10.5860/crl.64.1.6 |

|

81 |

Detlor, B.,

Julien, H., Willson, R., Serenko,

A., & Lavallee, M. (2011). Learning outcomes of information literacy

instruction at business schools. Journal

of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 62(3),

572–585. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.21474 |

|

76 |

Cooney, M., & Hiris, L.

(2003). Integrating information literacy and its assessment into a graduate

business course: A collaborative framework. Research Strategies, 19(3–4), 213–232. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resstr.2004.11.002 |

|

75 |

Klusek, L.,

& Bornstein, J. (2006). Information literacy skills for business careers:

Matching skills to the workplace. Journal

of Business & Finance Librarianship, 11(4), 3–21. https://doi.org/10.1300/J109v11n04_02 |

Discussion

Competing IL Standards and Frameworks

Citation

of the Standards in BIL peaked in

2012, more than a decade after they were adopted (see Figure 6). Adoption of

the Framework seems slow, and the

citations have actually decreased steadily since 2016. This is potentially due

to unfamiliarity with the document, which was finalized just four years ago,

coupled with the lengthy scholarly publishing process. However, there may well be

a spike in usage as more business librarians become knowledgeable about and

comfortable with it. ACRL has made a concerted effort to educate librarians on

the Framework and promote its use in

the information literacy instruction classroom. The ACRL publication Disciplinary Applications of Information Literacy

Threshold Concepts (Godbey, Wainscott, & Goodman, 2017) shared 25 examples of ways

that subject librarians have successfully incorporated the Framework into class content, and the book includes one example

from business-related disciplines. The widely popular ACRL Sandbox, which is an

open access repository where librarians can share lesson plans and activities

that incorporate the Framework, had

25 out of almost 225 lesson plans focused on business or economics at the time

of this writing (ACRL, 2020).

The

AACSB Standards were cited far less

often than the Standards but more

often than the Framework. While these

Standards do not specifically use the phrase “information literacy,” McInnis

Bowers et al. (2009) point out that “four of the six curricular standards for

quality management education put forth by AACSB International were closely tied

to information-literacy skills, namely, communication abilities, ethical

understanding and reasoning abilities, analytical skills, and use of

information technology” (p. 113). More than three-fourths of the articles that

cited the AACSB Standards also cited

the ALA Standards.

Figure 7

Original research and

practical application publications by year, 2000–2019.

Research or

Practice?

In

the BIL literature, original research and practical applications are the two

most common publication types. Both original research and practical application

publications generally increased in frequency between 2000 and 2019—although

original research increased more. Figure 7 shows a trend in the BIL literature,

beginning in 2010, in which original research was published more commonly than

practical application publications Practical applications publications are

common in the overall LIS literature, and the BIL subset is no exception. These

types of publications have been criticized for not being generalizable or

rigorous (Wilson, 2013, 2016). Potential explanations for this trend in LIS

have been explored, and a main reason for this is the lack of formalized

support for librarians to conduct their own research. Babb summarizes the issue

in this way: “Research carried out by librarians was considered important for

the profession, while often simultaneously considered extraneous to the

individual jobs of librarians” (Babb, 2017, p. ii). Wilson (2016) notes that

this issue is not unique to LIS, and that all disciplines have a range of

quality that appears in the literature. She recommends these six strategies or

areas for improvement in LIS research: confidence, collaboration, mentorship,

education, recognizing that practice makes better, and developing specific

research needs for specific areas of librarianship. It is important to keep in

mind, however, that the practical applications publications are highly valued

and used by librarians because they are, in fact, practitioners.

The survey method is clearly popular with LIS

practitioners and researchers. The prevalence of the survey method is not

surprising. A 2004 content analysis of “librarianship research” (Koufogiannakis, Slater, & Crumley, 2004) and a 2018

systematic review of LIS research (Ullah & Ameen, 2018) both found the

questionnaire/survey to be the most common method. Of the studies that used the

survey method, many used multiple types of surveys. For example, Camacho (2018)

reported on a project in which librarians and business faculty collaborated on

the development of instructional videos for a flipped classroom. The first

survey tested the IL skills of the students who had watched the video (e.g.,

“Why are peer-reviewed articles considered authoritative?”) (p. 30). A second

follow-up survey collected feedback on the new instructional videos (e.g.,

“What suggestions do you have for improving the videos in the future?”) (p.

33).

It seems that the survey method is often used to

demonstrate impact and effectiveness in the classroom. Half of the 62 survey

method publications had assessment as a topic, and many shared key findings

related to instruction impact (29 publications), IL skills (26 publications),

and student perceptions (24 publications). Atwong and

Heichman Taylor (2008), for example, developed a

survey “to measure students' self-reported knowledge before and after a

training module developed and conducted by librarian and faculty” in order to

demonstrate instruction impact (p. 433). Detlor et

al. (2011) used the standardized IL testing instrument SAILS, in conjunction

with interviews, to study undergraduate business students. Findings from this

paper indicated that students were skilled at evaluating sources but struggled

with search skills.

Researchers most often used IL self-assessment surveys

and pre- and posttests to study undergraduate business students, and IL

self-assessment surveys and IL skills surveys to study graduate business

students. Note that pre- and posttests and IL skills surveys may ask the same

types of questions (e.g., Which words in the following list are Boolean

operators?), but the IL skills survey is given just one time and the pre- and

posttest is given before and after some sort of IL intervention, such as a

tutorial or one-shot session. For example, a business librarian and a

communications librarian collaborated to develop new IL instruction for

undergraduate business students taking a public speaking course. Pre- and

posttest surveys using Likert-scale responses measured the effectiveness of the

IL sessions. Participants responded to statements such as “I feel comfortable

accessing business-related information through the library” (Nielsen &

Jetton, 2014, p. 347). In this case, the survey was both a pre- and posttest

and also an IL self-assessment. Cooney and Hiris

(2003) developed an Information Literacy Inventory, a survey instrument that

combined IL skills (e.g., “Information posted on the Internet is available for

fair use and is not covered by copyright restrictions. True or false?”) and IL

self-assessment questions (e.g., “How would you rate your comfort level in

conducting the research for the term paper required in this course?”) (p. 226,

227). The authors surveyed graduate business students taking a course on

international financial markets and used the findings to develop BIL

instruction for the MBA program.

Focus on Undergraduate Business Students

The BIL literature is generally focused on improving

instruction practice. Business librarians tend to spend much of their teaching

time with undergraduate students. In a 2019 survey, 90% of business librarian

respondents reported teaching undergraduate students, and 54% reporting

teaching graduate students (Houlihan, Wiley & Click, 2019).

Collaboration was a very common topic in the BIL

literature; 41% of the practical application and 31% of the original research

publications were about collaboration or faculty partnerships. The most common

types of author collaboration in this dataset were between two librarians or

between a librarian and a business professor. Librarian collaborators were more

likely to publish practical application papers. Original research publications

were more likely to be authored by a librarian and business faculty. These

findings support Wilson’s (2016) recommendation, noted previously in the

“Research or Practice?” section, that collaboration is an important strategy in

improving the quality of LIS research. Librarian’s collaborative efforts tended

to focus on teaching methods and strategies, which may explain why practical

application publications are more common with this population. For example,

librarians Detmering and Johnson (2011) describe the

revision of BIL instruction for an introductory course, “highlighting the

importance of thinking critically throughout the information-seeking process”

(p. 105) instead of demonstrating library tools. Papers authored by librarian

and business professor teams were, not surprisingly, often about collaboration

and faculty partnerships. Many of these publications focused on assessment

efforts as well. In one case, a business librarian and an accounting professor

collaborated to design a research assignment for a class on government and

nonprofit accounting (Finley & Waymire, 2012).

They assessed student IL skills by analyzing the bibliographies of the first

draft and final version of student papers. This article is notable because it

described one of the few librarian/business faculty collaborations in which the

librarian participated in the grading process.

Interdisciplinary collaboration on research has many

benefits. Scholars can experience personal growth as they learn to approach

research from a different perspective. They have the opportunity to learn about

different methods, models, and theories. This type of work can be especially

rewarding for business liaison librarians as they forge deeper connections with

the faculty they work with and learn more about the business research

landscape. In a recent study, Tran and Chan (in press) found that librarians

are motivated to seek research collaborators for a number of reasons, including

accessing needed expertise, seeking a sounding board, and sharing the research

workload. Respondents indicated that seeking collaborators in the workplace is

a preferred strategy. These findings all support the idea that business

librarians can benefit from collaborating with business faculty—and vice versa.

A cited reference search was conducted in Google Scholar

to identify the most impactful publications as illustrated in Table 6. Seven of

the top ten publications were published between 2000 and 2003, which is to be

expected; the longer a publication has been out, the more opportunity it has to

be cited by other scholars. Interestingly, five of the top ten publications

were written by authors outside of the United States, including the top two.

Six of the most highly cited publications present original research.

It is also interesting to note

that three of these publications appear in journals outside the LIS field (Studies in Higher Education, Journal of

Information Systems Education, and The

Internet and Higher Education). More than one-third of the publications

in the 135 paper dataset were published in the Journal of Business & Finance

Librarianship, but only one of the top 10 most highly cited articles was

published here. According to Google Scholar’s LIS journal rankings, three of

the journals represented here are considered top publications in the field: Journal of the American Society for

Information Science and Technology (JASIST), Journal of Information Science (JIS),

and College & Research Libraries (C&RL). In the complete dataset of 135 articles, these journals appear

eight times total: three articles in JASIST,

three in C&RL, and two in JIS. All eight were published more than

five years ago, with the exception of one C&RL

paper published in 2018.

While all of the publications shared findings or

described experiences, many did not provide specific recommendations for

practice. Of those that did, however, these recommendations most commonly fell

under one of the following categories: teaching methods and strategies,

collaboration, or assessment.

Teaching methods and strategies recommendations focused

on the flipped classroom, problem-based learning, and the use of business

models and concepts in IL. Cohen (2016) calls the flipped-instruction model a

“catalyst for collaboration” and recommends bringing “disciplinary faculty ‘on

board’ with homework assignments, in-class activities, assessment” and

supporting technologies (p. 20). Fiegen (2011), who

reviewed 30 years of BIL literature, advises librarians to adopt “a regular

practice of preassignments” (p. 287). Problem-based

learning was also regularly endorsed. Brock & Tabaei

(2011) recommend “using real-life problems and scenarios to encourage the

development of information literacy skills” (p. 367), while Devasagayam,

Johns-Masten, and McCollum (2012) suggest

“experiential exercises that demand involvement, engagement, application, and

reinforcement through repetition” (p. 6). Authors also recommend that

librarians use methods, frameworks, and concepts that are familiar to business

students when teaching BIL. O’Neill (2015) uses the Business Canvas Model, a

“popular tool for helping entrepreneurs plan and iterate their business

concepts,” in the BIL classroom (p. 458). Others recommend using the case

method, which students regularly encounter in their business classes, to teach

BIL concepts (Spackman & Camacho, 2009; Stonebraker

& Howard, 2018).

The nature of teaching in this discipline is more

practical than theoretical since BIL requires a unique set of knowledge and

search skills. The low number of theories and models used as well as the scant

evidence for implementation of the Framework

could indicate that some librarians teaching business prioritize teaching

disciplinary knowledge over more abstract information literacy concepts.

The many recommendations related to collaboration tended

to be vague in nature, positing that collaboration between librarians and

business faculty is important and necessary but giving few practical ideas for

how to build these relationships. The literature does, however, identify some

specific ways that librarians and business faculty can work together, including

identifying resources for purchase (Camacho, 2015), supporting experiential

learning (Griffis, 2014), identifying skills gaps

(Macy & Coates, 2016), and developing IL outcomes (Stagg & Kimmins, 2014).

The assessment recommendations ranged from general calls

for more assessment to the recommendation of specific methods. As a result of

her review of the BIL literature, Fiegan (2011)

recommends pre- and posttests and graded assessments. In our study, we tracked

the number of publications in which librarians were part of the grading

process, and six met this criterion. Examples of librarians participating in

the grading process included Strittmater’s (2012)

study about a faculty-librarian collaboration in which the author creates

online exercises and participates in the grading process. Additionally,

librarian-business professor team Cooney and Hiris

(2003) collaboratively graded term papers for IL related skills based on a

checklist. Other methods are recommended as well, including reflective writing

(McKinney & Sen, 2012), rubrics (Mezick &

Harris, 2016), and systematic reviews (Fiegen, 2010).

Sokoloff and Simmons (2015) write about the value of citation analysis but note

that “the method would elicit more meaningful results in the presence of other,

complementary evidence” (p. 170).

This scoping review was designed to explore the last two

decades of BIL research, in order to support LIS practitioners in their evidence based practice. Findings indicated a dependence on

the survey method in BIL research, a focus on collaboration between business

librarians and business faculty, interest in new teaching methods, and a

hesitation to implement the ACRL Framework

in BIL. With the introduction of the Framework

in 2015, all teaching librarians have the opportunity to rethink

information literacy efforts based on this new paradigm. While there is an

abundance of literature about the ACRL Framework

and threshold concepts, relatively little literature exists that specifically

focuses on how business librarians have utilized this document to improve

information literacy assignments, lesson plans, learning activities, and

assessments. Further research on this topic would help inform efforts to

integrate the Framework into BIL.

An, A., & Quail, S. (2018).

Building BRYT: A case study in developing an online toolkit to promote business

information literacy in higher education. Journal

of Library & Information Services in Distance Learning, 12(3/4), 71–89.

https://doi.org/10.1080/1533290X.2018.1498615

Arksey, H., & O'Malley, L.

(2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research

Methodology, 8(1), 19–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000119616

Association of College & Research Libraries (ACRL). (2000). Information literacy competency standards

for higher education. http://hdl.handle.net/11213/7668

Association of College &

Research Libraries (ACRL). (2015). Framework

for information literacy for higher education. http://www.ala.org/acrl/standards/ilframework

Association of College &

Research Libraries (ACRL). (2020). ACRL Framework for Information Literacy

Sandbox. https://sandbox.acrl.org/

Atwong, C. T., & Heichman Taylor,

L. J. (2008). Integrating information literacy into business education: A

successful case of faculty-librarian collaboration. Journal of Business & Finance Librarianship, 13(4), 433–448. https://doi.org/10.1080/08963560802202227

Babb, M. N. (2017). An

exploration of academic librarians as researchers within a university setting

[Master’s thesis, University of Alberta]. Education and Research Archive. https://era.library.ualberta.ca/items/15c87b25-5656-41c6-9242-42a0fb7ed74c

Bauer, M. (2018). Ethnographic

study of business students' information-seeking behavior: Implications for

improved library practices. Journal of

Business & Finance Librarianship, 23(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1080/08963568.2018.1449557

Bayliss, G. (2013). Exploring

the cautionary attitude toward Wikipedia in higher education: Implications for

higher education institutions. New Review

of Academic Librarianship, 19(1),

36–57. https://doi.org/10.1080/13614533.2012.740439

Brien, S. E., Lorenzetti, D.

L., Lewis, S., Kennedy, J., & Ghali, W. A.

(2010). Overview of a formal scoping review on health system report cards. Implementation Science, 5(2). https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-5-2

Brock, S., & Tabaei, S. (2011). Library and marketing class collaborate

to create next generation learning landscape. Reference Services Review, 39(3), 362–368. https://doi.org/10.1108/00907321111161377

Bryant, N. P., & Hooper, R.

S. (2017). Learning to learn: Using an embedded librarian to develop web-based

legal information literacy for the business student. Southern Law Journal, 27(2),

387–416.

Camacho, L. (2015). The

communication skills accounting firms desire in new hires. Journal of Business & Finance Librarianship, 20(4), 318–329. https://doi.org/10.1080/08963568.2015.1072895

Camacho, L. (2018). If we built

it, would they come? Creating instruction videos with promotion in mind. Journal of Business & Finance

Librarianship, 23(1), 26–34. https://doi.org/10.1080/08963568.2018.1431867

Cohen, M. E. (2016). The

flipped classroom as a tool for engaging discipline faculty in collaboration: A

case study in library-business collaboration. New Review of Academic Librarianship, 22(1), 5–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/13614533.2015.1073162

Cooney, M. (2005). Business

information literacy instruction: A survey and progress report. Journal of Business & Finance

Librarianship, 11(1), 3–25. https://doi.org/10.1300/j109v11n01_02

Cooney, M., & Hiris, L. (2003). Integrating information literacy and its

assessment into a graduate business course: A collaborative framework. Research Strategies, 19(3–4), 213–232. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resstr.2004.11.002

Daudt, H. M., van Mossel, C., & Scott, S. J. (2013).

Enhancing the scoping study methodology: A large, inter-professional team’s

experience with Arksey and O’Malley’s framework. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 13(48). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-13-48

Detlor, B., Julien, H., Willson, R., Serenko, A., & Lavallee, M. (2011). Learning outcomes

of information literacy instruction at business schools. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology,

62(3), 572–585. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.21474

Detmering, R., & Johnson, A. M. (2011). Focusing on the

thinking, not the tools: Incorporating critical thinking into an information

literacy module for an introduction to business course. Journal of Business & Finance Librarianship, 16(2), 101–107. https://doi.org/10.1080/08963568.2011.554771

Devasagayam, R., Johns-Masten, K., &

McCollum, J. (2012). Linking information literacy, experiential learning, and

student characteristics: Pedagogical possibilities in business education. Academy of Educational Leadership Journal,

16(4).

Donaldson, K. A. (2000).

Library research success: Designing an online tutorial to teach information

literacy skills to first-year students. The

Internet and Higher Education, 2(4), 237–251. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1096-7516(00)00025-7

Fiegen, A. M. (2010). Systematic review of research methods:

The case of business instruction. Reference

Services Review, 38(3), 385–397. https://doi.org/10.1108/00907321011070883

Fiegen, A. M. (2011). Business information literacy: A

synthesis for best practices. Journal of

Business & Finance Librarianship, 16(4), 267–288. https://doi.org/10.1080/08963568.2011.606095

Fiegen, A. M., Cherry, B., & Watson, K. (2002). Reflections

on collaboration: Learning outcomes and information literacy assessment in the

business curriculum. Reference Services

Review, 30(4), 307–318. https://doi.org/10.1108/00907320210451295

Finley, W., & Waymire, T. (2012). Information literacy in the accounting

classroom: A collaborative effort. Journal

of Business & Finance Librarianship, 17(1), 34–50. https://doi.org/10.1080/08963568.2012.629566

Fournier, K., & Sikora, L.

(2015). Individualized research consultations in academic libraries: A scoping

review of practice and evaluation methods. Evidence

Based Library and Information Practice, 10(4), 247–267. https://doi.org/10.18438/b8zc7w

Gardois, P., Colombi, N., Grillo, G.,

& Villanacci, M. C. (2012). Implementation of Web

2.0 services in academic, medical and research libraries: a scoping review. Health Information & Libraries Journal,

29(2), 90–109. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-1842.2012.00984.x

Godbey, S., Wainscott, S. &

Goodman, X. (2017). Disciplinary

applications of information literacy threshold concepts. Chicago, IL: Association of College and Research Libraries. https://www.alastore.ala.org/content/disciplinary-applications-information-literacy-threshold-concepts

Gilbert, S. (2017). Information

literacy skills in the workplace: Examining early career advertising

professionals. Journal of Business &

Finance Librarianship, 22(2),

111–134. https://doi.org/10.1080/08963568.2016.1258938

Gong, X., & Loomis, M.

(2009). An empirical study on follow-up library instruction sessions in the

classroom. Electronic Journal of Academic

and Special Librarianship, 10(1).

https://southernlibrarianship.icaap.org/content/v10n01/gong_x01.html

Griffis, P. J. (2014). Information literacy in business

education experiential learning programs. Journal

of Business & Finance Librarianship, 19(4), 333–341. https://doi.org/10.1080/08963568.2014.952987

Guth, L., & Sachs, D. E. (2018). National trends in

adoption of ACRL information literacy guidelines and impact on business

instruction practices: 2003–2015. Journal

of Business & Finance Librarianship, 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/08963568.2018.1467169

Heyns, E. P., Eldermire, E. R. B.,

& Howard, H. A. (2019). Unsubstantiated conclusions: A scoping review on

generational differences of leadership in academic libraries. Journal of Academic Librarianship, 45(5).

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2019.102054

Houlihan, M., Wiley, C., &

Click, A. (2019). Information literacy survey of business librarians

[Unpublished raw data].

Jefferson, C. O. (2019). Good

for business: Applying the ACRL Framework threshold concepts to teach a

learner-centered business research course. Ticker:

The Academic Business Librarianship Review, 2(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.3998/ticker.16481003.0002.101

Johnston, B., & Webber, S.

(2003). Information literacy in higher education: A review and case study. Studies in Higher Education, 28(3),

335–352. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075070309295

Katz, I. R., Haras, C., & Blaszczynski, C.

(2010). Does business writing require information literacy? Business Communication Quarterly, 73(2), 135–149. https://doi.org/10.1177/1080569910365892

Kjellberg, S., Haider, J., & Sundin,

O. (2016). Researchers' use of social network sites: A scoping review. Library & Information Science Research,

38(3), 224–234. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lisr.2016.08.008

Klusek, L., & Bornstein, J. (2006). Information literacy

skills for business careers: Matching skills to the workplace. Journal of Business & Finance

Librarianship, 11(4), 3–21. https://doi.org/10.1300/J109v11n04_02

Koufogiannakis D. (2012). The state of systematic reviews in library

and information studies. Evidence Based

Library and Information Practice, 7(2), 91–95. https://doi.org/10.18438/B8Q021

Koufogiannakis, D., Slater, L., & Crumley, E. (2004). A content

analysis of librarianship research. Journal

of Information Science, 30(3),

227–239. https://doi.org/10.1177/0165551504044668

Leighton, H. V., & May, D.

(2013). The library course page and instruction: Perceived helpfulness and use

among students. Internet Reference

Services Quarterly, 18(2),

127–138. https://doi.org/10.1080/10875301.2013.804019

Lombardo, S. V., & Miree, C. E. (2003). Caught in the web: The impact of

library instruction on business students' perceptions and use of print and

online resources. College & Research

Libraries, 64(1), 6–22. https://doi.org/10.5860/crl.64.1.6

Lorenzetti, D. L., & Powelson, S. E. (2015). A scoping review of mentoring programs

for academic librarians. The Journal of

Academic Librarianship, 41(2), 186–196. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2014.12.001

McInnis Bowers, C. V., Chew,

B., Bowers, M. R., Ford, C. E., Smith, C., & Herrington, C. (2009).

Interdisciplinary synergy: A partnership between business and library faculty

and its effects on students’ information literacy. Journal of Business & Finance Librarianship, 14(2), 110–127. https://doi.org/10.1080/08963560802362179

Macy, K. V., & Coates, H.

L. (2016). Data information literacy instruction in business and public health.

IFLA Journal, 42(4), 313–327. https://doi.org/10.1177/0340035216673382

Matesic, M. A., & Adams, J. M. (2008). Provocation to learn:

A study in the use of personal response systems in information literacy

instruction. Partnership: The Canadian

Journal of Library and Information Practice and Research, 3(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.21083/partnership.v3i1.327

McKinney, P., & Sen, B. A.

(2012). Reflection for learning: Understanding the value of reflective writing

for information literacy development. Journal

of Information Literacy, 6(2), 110–129. https://ojs.lboro.ac.uk/JIL/article/view/LLC-V6-I2-2012-5

Mezick, E. M., & Hiris, L.

(2016). Using rubrics for assessing information literacy in the finance

classroom: A collaboration. Journal of

Business & Finance Librarianship, 21(2), 95–113. https://doi.org/10.1080/08963568.2016.1169970

National Center for Education

Statistics. (2017). Bachelor's degrees conferred by postsecondary institutions,

by field of study: Selected years, 1970-71 through 2016-17. Digest of Educational Statistics. https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d18/tables/dt18_322.10.asp

Nielsen, J., & Jetton, L.

L. (2014). Assessing the effectiveness of collaborative subject specific

library instruction. Qualitative and

Quantitative Methods in Libraries, 3(1), 343–350. http://qqml-journal.net/index.php/qqml/article/view/143

Nentl, N., & Zietlow, R. (2008).

Using Bloom's taxonomy to teach critical thinking skills to business students. College & Undergraduate Libraries, 15(1–2),

159–172. https://doi.org/10.1080/10691310802177135

Nisonger, T., & Davis, C. (2005). The perception of library

and information science journals by LIS education deans and ARL library

directors: A replication of the Kohl–Davis study. College & Research Libraries, 66(4), 341–377. https://doi.org/10.5860/crl.66.4.341

O’Neill, T. W. (2015). The

Business Model Canvas as a platform for business information literacy

instruction. Reference Services Review,

43(3), 450–460. https://doi.org/10.1108/rsr-02-2015-0013

O’Sullivan, C. (2002). Is

information literacy relevant in the real world? Reference Services Review, 30(1), 7–14. https://doi.org/10.1108/00907320210416492

Rodríguez, K., Cádiz, L., &

Penkova, S. (2018). Integration of information

literacy skills into the core business curriculum at the University of Puerto

Rico Río Piedras. Journal of Business

& Finance Librarianship, 23(2),

117–130. https://doi.org/10.1080/08963568.2018.1467168

Spackman, A., & Camacho, L.

(2009). Rendering information literacy relevant: A case-based pedagogy. The Journal of Academic Librarianship, 35(6),

548–554. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2009.08.005

Stonebraker, I., & Fundator, R.

(2016). Use it or lose it? A longitudinal performance assessment of

undergraduate business students' information literacy. The Journal of Academic Librarianship, 42(4), 438–444. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2016.04.004

Stonebraker, I., & Howard, H. A. (2018). Evidence-based

decision-making: Awareness, process and practice in the management classroom. The Journal of Academic Librarianship, 44(1),

113–117. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2017.09.017

Sokoloff, J., & Simmons, R.

(2015). Evaluating citation analysis as a measurement of business librarian

consultation impact. Journal of Business

& Finance Librarianship, 20(3), 159–171. https://doi.org/10.1080/08963568.2015.1046783

Stagg, A., & Kimmins, L. (2014). First year in higher education (FYHE)

and the coursework post-graduate student. The

Journal of Academic Librarianship, 40(2), 142–151. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2014.02.005

Strittmatter, C. (2012). Developing and assessing

a library instruction module for a core business class. Journal of Business & Finance Librarianship, 17(1), 95–105. –https://doi.org/10.1080/08963568.2012.630645

Quinn, T., & Leligdon, L. (2014). Executive MBA students’ information

skills and knowledge: Discovering the difference between work and academics. Journal of Business & Finance

Librarianship, 19(3), 234–255. https://doi.org/10.1080/08963568.2014.916540

Tran, N-Y., & Chan, E. (in

press). Seeking and finding research collaborators: An exploratory study of

librarian motivations, strategies, and success rates. College & Research Libraries. https://works.bepress.com/yen-tran/25/

Ullah, A., & Ameen, K.

(2018). Account of methodologies and methods applied in LIS research: A

systematic review. Library &

Information Science Research, 40(1), 53–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lisr.2018.03.002

Webber, S., & Johnston, B.

(2000). Conceptions of information literacy: New perspectives and implications.

Journal of Information Science, 26(6),

381–397. https://doi.org/10.1177/016555150002600602

Williams, J., & Chinn, S. J.

(2009). Using Web 2.0 to support the active learning experience. Journal of Information Systems Education, 20(2),

165–174. Available at http://jise.org/volume20/n2/JISEv20n2p165.html

Wilson, V. (2013). Formalized

curiosity: reflecting on the librarian practitioner-researcher. Evidence Based Library and Information

Practice, 8(1), 111–117. https://doi.org/10.18438/B8ZK6K

Wilson, V. (2016). Librarian

research: Making it better? Evidence

Based Library and Information Practice, 11(1),

111–114. https://doi.org/10.18438/B8VD0N

Appendix A

Codebook for Research

Topics, Key Findings, and Recommendations

Active learning

Assessment

Case study (student assignment)

Client-based projects/student consulting/problem-based

learning

Collaboration/faculty partnerships

Credit-bearing courses

Critical thinking

Data literacy

Embedded librarianship

Evaluation of information

Financial literacy

ACRL Framework

Information literacy skills

Information literacy standards

Information access

Information seeking behavior

Instruction impact

International libraries

Non-traditional students

One-shot sessions

Online resources

Online teaching

Online tutorials

Orientation

Outreach

Reference services

Scholarly communication

Student perceptions

Teaching methods & strategies

Technology

Appendix B

All Included Publications

- Akhras, C. (2013). Interactive

technology: Enhancing business students’ content literacy. Procedia - Social and Behavioral

Sciences, 83, 332–336. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2013.06.065

- An, A., &

Quail, S. (2018). Building BRYT: A case study in developing an online

toolkit to promote business information literacy in higher education. Journal of Library & Information

Services in Distance Learning, 12(3/4), 71–89. https://doi.org/10.1080/1533290X.2018.1498615

- Artemchik, T. (2016).

Using the instructional design process in tutorial development. Reference Services Review, 44(3),

309–323. https://doi.org/10.1108/rsr-12-2015-0050

- Atwong, C. T., & Heichman Taylor, L. J. (2008). Integrating information

literacy into business education: A successful case of faculty-librarian

collaboration. Journal of Business

& Finance Librarianship, 13(4), 433–448. https://doi.org/10.1080/08963560802202227

- Bauer, M.

(2018). Ethnographic study of business students' information-seeking

behavior: implications for improved library practices. Journal of Business & Finance

Librarianship, 23(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1080/08963568.2018.1449557

- Baxter, K.,

Johnson, B., & Chisholm, K. (2016). Evaluating and developing an

information literacy programme for MBA students.

New Zealand Library &

Information Management Journal, 56(1), 30–45. https://ndhadeliver.natlib.govt.nz/delivery/DeliveryManagerServlet?dps_pid=IE26797875

- Bayliss, G.

(2013). Exploring the cautionary attitude toward Wikipedia in higher

education: Implications for higher education institutions. New Review of Academic Librarianship,

19(1), 36–57. https://doi.org/10.1080/13614533.2012.740439

- Booker, L. D.,

Detlor, B., & Serenko,

A. (2012). Factors affecting the adoption of online library resources by

business students. Journal of the

American Society for Information Science and Technology, 63(12),

2503–2520. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.22723

- Borg, M.,

& Stretton, E. (2009). My students and other animals. Or a vulture, an

orb weaver spider, a giant panda and 900 undergraduate business students

.... Journal of Information

Literacy, 3(1), 19–30. https://ojs.lboro.ac.uk/JIL/article/view/219

- Boss, K.,

& Drabinski, E. (2014). Evidence-based

instruction integration: A syllabus analysis project. Reference Services Review, 42(2), 263–276. https://doi.org/10.1108/rsr-07-2013-0038

- Bravo, R.,

Lucia, L., & Martin, M. J. (2013). Assessing a web library program for

information literacy learning. Reference

Services Review, 41(4), 623–638. https://doi.org/10.1108/rsr-05-2013-0025

- Brock, S.,

& Tabaei, S. (2011). Library and marketing

class collaborate to create next generation learning landscape. Reference Services Review, 39(3),

362–368. https://doi.org/10.1108/00907321111161377

- Brodsky, M.

(2019). The role of business librarians in teaching data literacy. Ticker: The Academic Business

Librarianship Review, 1(3), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.3998/ticker.16481003.0001.301

- Bryant, N. P.,

& Hooper, R. S. (2017). Learning to learn: Using an embedded librarian

to develop web-based legal information literacy for the business student. Southern Law Journal, 27(2), 387–416.

- Camacho, L.

(2015). The communication skills accounting firms desire in new hires. Journal of Business & Finance

Librarianship, 20(4), 318–329. https://doi.org/10.1080/08963568.2015.1072895

- Camacho, L.

(2018). If we built it, would they come? Creating instruction videos with

promotion in mind. Journal of

Business & Finance Librarianship, 23(1), 26–34. https://doi.org/10.1080/08963568.2018.1431867

- Campbell, D.

K. (2011). Broad focus, narrow focus: A look at information literacy

across a school of business and within a capstone course. Journal of Business & Finance

Librarianship, 16(4), 307–325. https://doi.org/10.1080/08963568.2011.605622

- Cochrane, C.

(2006). Embedding information literacy in an undergraduate management

degree: lecturers' and students' perspectives. Education for Information, 24(2-3), 97–123. https://doi.org/10.3233/efi-2006-242-301

- Cohen, M. E.

(2016). The flipped classroom as a tool for engaging discipline faculty in

collaboration: A case study in library-business collaboration. New Review of Academic Librarianship,

22(1), 5–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/13614533.2015.1073162

- Cohen, M. E.,

Poggiali, J., Lehner-Quam, A., Wright, R., &

West, R. K. (2016). Flipping the classroom in business and education

one-shot sessions: A research study. Journal

of Information Literacy, 10(2), 40–63. https://ojs.lboro.ac.uk/JIL/article/view/PRA-V10-I2-3

- Conley, T. M.,

& Gil, E. L. (2011). Information literacy for undergraduate business

students: Examining value, relevancy, and implications for the new

century. Journal of Business &

Finance Librarianship, 16(3), 213–228. https://doi.org/10.1080/08963568.2011.581562

- Cooney, M.

(2005). Business information literacy instruction: A survey and progress

report. Journal of Business &

Finance Librarianship, 11(1),

3–25. https://doi.org/10.1300/j109v11n01_02

- Cooney, M.,

& Hiris, L. (2003). Integrating information

literacy and its assessment into a graduate business course: A

collaborative framework. Research

Strategies, 19(3-4), 213–232. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resstr.2004.11.002

- Costa, C.

(2009). Use of online information resources by RMIT University economics,

finance, and marketing students participating in a cooperative education

program. Australian Academic &

Research Libraries, 40(1), 36–49. https://doi.org/10.1080/00048623.2009.10721377

- Cramer, S.,

Campbell, D. K., & Scanlon, M. G. (2019). Increasing research quality

in entrepreneurial students: Best practices in faculty-librarian

partnerships. Ticker: The Academic

Business Librarianship Review, 2(1), 18–25. https://doi.org/10.3998/ticker.16481003.0002.102

- Cullen, A.

(2013). Using the case method to introduce information skill development

in the MBA curriculum. Journal of

Business & Finance Librarianship, 18(3), 208–232. https://doi.org/10.1080/08963568.2013.795740

- Cullen, J. G.

(2013). Applying RADAR with new business postgraduates. Journal of Information Science, 40(1),

25–27. https://doi.org/10.1177/0165551513510094

- Cunningham, N.

A., & Anderson, S. C. (2005). A bridge to FARS and information

literacy for accounting undergraduates. Journal of Business & Finance Librarianship, 10(3), 3–16. https://doi.org/10.1300/j109v10n03_02

- D’Angelo, B.

J. (2001). Using source analysis to promote critical thinking. Research Strategies, 18(4),

303–309. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0734-3310(03)00006-5

- Decarie, C. (2012). Dead or

alive: Information literacy and dead(?) celebrities. Business Communication Quarterly, 75(2), 166–172. https://doi.org/10.1177/1080569911432737

- Detlor, B., Julien, H., Willson, R., Serenko, A.,

& Lavallee, M. (2011). Learning outcomes of information literacy

instruction at business schools. Journal

of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 62(3), 572–585. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.21474

- Detmering, R., &

Johnson, A. M. (2011). Focusing on the thinking, not the tools:

Incorporating critical thinking into an information literacy module for an

introduction to business course. Journal

of Business & Finance Librarianship, 16(2), 101–107. https://doi.org/10.1080/08963568.2011.554771

- Devasagayam, R., Johns-Masten, K., & McCollum, J. (2012). Linking

information literacy, experiential learning, and student characteristics:

Pedagogical possibilities in business education. Academy of Educational Leadership Journal, 16(4).

- Donaldson, K.

A. (2000). Library research success: Designing an online tutorial to teach

information literacy skills to first-year students. The Internet and Higher Education, 2(4), 237–251. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1096-7516(00)00025-7

- Dubicki, E.

(2010). Research behavior patterns of business students. Reference Services Review, 38(3),

360–384. https://doi.org/10.1108/00907321011070874

- Dunaway, M.

K., & Orblych, M. T. (2011). Formative

assessment: Transforming information literacy instruction. Reference Services Review, 39(1),