Research Article

Age as a Predictor of Burnout in Russian Public

Librarians

Nikita Kolachev

Research Assistant

International Laboratory of

Positive Psychology of Personality and Motivation

National Research University

Higher School of Economics

Moscow, Russian Federation

Email: nkolachev@hse.ru

Igor Novikov

Scientific Secretary

Moscow Governorate Universal

Library

Moscow, Russian Federation

Email: novikov@gumbo.ru

Received: 20 Mar. 2019 Accepted: 17 Sep. 2020

![]() 2020 Kolachev and Novikov. This is an Open Access article distributed under

the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

2020 Kolachev and Novikov. This is an Open Access article distributed under

the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

DOI: 10.18438/eblip29753

Abstract

Objective – Increasing life expectancy leads to an increase in

the mean age of the workforce. The aging workforce implies new challenges for

management and human resources. Existing findings on relations between age and

burnout are controversial and scarce. Also, the problem

of burnout amongst library workers in Russia has received little attention from

researchers.

Methods – The studied sample consisted of 620 public

librarians from 166 public libraries of different regions (the Moscow region, Yaroslavl,

Chelyabinsk, Novosibirsk, Astrakhan, and Republic of Buryatia) of the Russian

Federation, who completed a self-reported online survey. For measuring burnout,

a new Burnout Assessment Tool was implemented. To examine the associations of

interest, we used structural equation modeling with a group correction

approach. In addition, library location, general self-efficacy, and length of

employment at the current workplace were utilized as predictors. All

statistical analysis was performed in R.

Results – Findings confirmed the hypotheses partially and

revealed negative links between exhaustion, mental distance, and cognitive

control and age, while reduced emotional control did not relate to age. Urban

librarians tended to demonstrate higher levels of mental distance and had more

significant problems with emotional regulation than their rural counterparts.

Also, the non-Moscow region librarians did not demonstrate correlations between

age and reduced cognitive control. Moreover, they showed a positive link

between age and reduced emotional control.

Conclusion – The current paper confirmed some previous results

on the negative relations between burnout symptoms and chronological age. The

results suggest the existence of higher risks of burnout for younger library

workers. Potential mechanisms underlying the resilience of older workers are

discussed.

Introduction

Increasing life expectancy leads to an increase in the mean age of the

workforce (Adams & Shultz, 2018). The aging workforce implies new challenges for management and human

resources. According to a Canadian report

of 2018, for one employee of 25 to 34 years, there was one employee aged 55 and

older (Statistics Canada, 2019). A similar situation is observed in the

European Union. According to Eurostat (2020), in the first quarter of 2012,

there were 13% of employees aged 55-64; in the first quarter of 2015, there

were 15% of employees aged 55-64; and in the first quarter of 2019, there were

17% of employees aged 55-64. Librarianship is not an exception. According to Wilder’s (2018) findings, the average age of employees

of the Association of Research Libraries increased by 2015 as the proportion of

workers aged 60 and over grew. In this sample, the mean age was 49 years.

Unfortunately, in the Russian Federation, there are no appropriate library

statistics; however, the situation seems analogous. According

to a statistical report from the Russian State Library, the mean age of its

personnel in 2019 was 48.90 years (Russian State Library, 2020). In a recent

study of librarians of the Moscow region, the participants’ mean age was 48.05

(Kolachev,

Osin, Schaufeli, & Desart,

2019).

Burnout amongst Russian library workers has received

little attention from researchers. Librarians are not considered a part of the

more socially important professions, like teachers, nurses, physicians, and

social workers. However, librarianship belongs to the human services, where

short-term contacts with clients are the primary source of stress (Salyers et

al., 2019). Some researchers refer to librarianship as a helping profession, in

which assistance to those who are staying in need, the frequency of such

requirements, and the limitation of available resources often lead to stress

(Smith & Nelson, 1983). In addition to general burnout factors (i.e.,

gender, age, personality, locus of control, expectations) and organizational

factors (i.e., excessive workload, underemployment, employee conflict, role

conflict), McCormack and Cotter (2013) mentioned a specific stress factor for

library workers: boredom with the routine nature of library work and little

intellectual stimulation. In addition to the harm of burnout for librarians

themselves, it can degrade the quality of services provided, thereby affecting

the satisfaction of library visitors.

Literature Review

A crucial problem that influences an employee’s

performance is work-related stress and its severe form: burnout (Penz et al., 2018). To date, the most common

definition of the term “burnout” is Maslach, Schaufeli, and Leiter's (2001)

interpretation: burnout is a state of physical and psychological exhaustion,

which develops as a reaction to stressful long-term working conditions.

According to the authors, burnout consists of three separate but interrelated

constructs: emotional exhaustion, cynicism/depersonalization, and lack of

accomplishment (inefficacy). Emotional exhaustion is the most common symptom of

burnout and is an emotional and physical sensation of exhaustion from excessive

workload. Cynicism implies an excessively detached attitude to various aspects

of work. Lack of accomplishment refers to a sense of incompetence and reduced

production of labour. The model has been common in various studies for almost

30 years, but it is not quite up-to-date with current understandings of burnout

syndrome, since we know that burnout also links to emotional and cognitive

impairments (Deligkaris, Panagopoulou, Montgomery,

& Masoura, 2014).

In a recently developed model by Schaufeli, De Witte,

and Desart (2019), burnout syndrome is characterized

by extreme fatigue, reduced ability to regulate cognitive and emotional

processes, as well as detachment in solving problems, depressed mood, as well

as non-specific psychological and psychosomatic symptoms. According to the

authors, this is developed by an imbalance between high job demands and low

levels of organizational resources (for reviewing the job demands-resources

model, Xanthopoulou, Bakker, Demerouti, &

Schaufeli, 2007). Primary symptoms include emotional exhaustion, mental

distance (the same as cynicism/depersonalization in Maslach et al.’s model),

reduced emotional control, and reduced cognitive control. Emotional exhaustion

refers to a feeling of either physical or mental exhaustion, or lack of energy.

Mental distance is about aversion to work, such as avoiding contact with others

at work. Reduced emotional control (emotional impairment) includes irritability

and emotional overreacting. Reduced cognitive control (cognitive impairment)

supposes attention and memory problems such as forgetfulness or concentration

deficits.

In the field of burnout research, much attention has

been paid to the dispositional and organizational factors that associate with

this syndrome (Bakker & Demerouti, 2007; Bianchi, 2018;

McManus, Keeling, & Paice, 2004). In some

studies, age negatively predicted burnout symptoms such as exhaustion and

cynicism/depersonalization (Maslach et al., 2001; Rutledge & Francis,

2004); however, it was usually used as a control variable, and a limited number

of researchers found that it played a role.

Existing scientific works on the connections between

age and burnout emphasize that younger employees are more prone to experience

burnout (Randall, 2007). In a

representative sample of the Finnish population, Ahola, Honkonen, Virtanen, Aromaa, and Lönnqvist (2008) confirmed that the negative association

between age and burnous is solely attributed to a subsample of young female

persons. In recent research, Marchand, Blanc, and Beauregard (2018) showed that

age non-linearly relates to burnout and its components. In particular, there

was a positive connection between age and either burnout or exhaustion until

the age of 30, then a negative one until the age of 55 (quadratic polynomial),

and then again, a positive pattern (cubic polynomial). At the same time,

cynicism and a lack of personal accomplishment negatively linked to age. Recent

research conducted of librarians of the Moscow region showed that age was a

significant predictor of general burnout, pointing out that younger workers are

more prone to experience burnout (Kolachev et al.,

2019).

Results concerning exhaustion and

cynicism/depersonalization are quite clear. Recently discovered symptoms

(reduced emotional control and reduced cognitive control) of burnout are of

interest. According to Johnson, Machowski,

Holdsworth, Kern, and Zapf's (2017) findings, age predicts less burnout because

of emotion regulation strategies. This means that older workers who have more

emotional experience apply effective coping strategies against burnout;

moreover, they pay more attention to emotional states than their younger

counterparts. Many other studies support the idea of

higher emotional control in older people (Doerwald, Scheibe, Zacher,

& Van Yperen, 2016; Mauno,

Ruokolainen, & Kinnunen,

2013). One of the explanations for this phenomenon is that older people

demonstrate a higher motivation to avoid negative situations and try to enjoy

life more, as they realize the finiteness of existence (Johnson et al., 2017).

So, we may expect that older workers are more effective when dealing with

emotional disturbances associated with burnout.

Another factor that enters into this

picture is the role of cognitive abilities, and it is well known that cognitive

abilities decline with aging. Theorists admit that more severe changes occur in

attention since performance on complex attentional tasks is worse in older people

(Murman, 2015). Moreover, so-called fluid cognitive

functions, such as processing speed and reasoning, also diminish with aging

(Deary et al., 2009). Burnout does not improve cognitive functions either. In

their systematic review, Deligkaris et al. (2014)

revealed that burnout primarily links to problems with executive functions

(working memory, inhibitory control, and task switching). Primarily,

respondents with lower levels of burnout perform better on N-back and Stroop

tasks (Diestel, Cosmar,

& Schmidt, 2013); in other words, people with higher levels of

burnout demonstrate less inhibitory control and working memory capacity.

Therefore, we may predict that age positively correlates with reduced cognitive

control in burnout, since the older respondents are, the more cognitive

deficits they have.

Aims

In this study, we aimed to examine

whether linear patterns between age and burnout symptoms are observed in

librarians. In addition, we were interested in revealing whether the new

constructs of reduced emotional and reduced cognitive control link to age in a

manner similar to exhaustion and distance (depersonalization).

Based on the literature review, we

hypothesized:

·

H1 – younger workers

experience higher levels of exhaustion and mental distance;

·

H2 – younger librarians

demonstrate lower emotional control than their older counterparts;

·

H3 – older librarians

demonstrate lower cognitive control than their younger counterparts.

Methods

Context

According to the Federalniy zakon №78 [Federal Law №78] of 1994, the library

system in Russia is represented by the following types of libraries: national,

federal, regional, municipal, research, university, organizational, private,

and funded by citizen groups. The four former libraries constitute the system

of public libraries (Zverevich, 2014). There are

41,821 public libraries; amongst them, 79% are rural libraries, and 21% are

urban (National Library of Russia, 2020). The number of registered users who

visit a library 9.4 times per year was 43,371,700 persons in 2018 (Main

Information and Computing Center of the Ministry of Culture of Russia, 2018),

which is equal to approximately 30% of the total population (Federal State

Statistics Service, 2019).

Descriptive Statistics of the Demographic Variables

|

|

M/% |

SD |

|

Age |

47.36 |

11.91 |

|

Gender (% of females) |

95% |

- |

|

Education (% of those who have a higher education degree) |

76% |

- |

|

Length of employment |

15.09 |

12.47 |

|

Library location (% of participants from urban areas) |

61% |

- |

Participants

Initially, we sent invitation letters

to library directors across the country. We got responses from 600 libraries.

Then we took a random sample of 305 libraries and sent the link to the

questionnaire. The invitation to participate was sent to a library director who

distributed the survey to all staff in the library. In total, 620 librarians

from 166 public libraries of different regions of the Russian Federation

completed the survey (response rate at the library level = 54%). Sixty-six percent

of the participants were from libraries in the Moscow region (central Russia),

8% from Novosibirsk (Siberia), 7% from Chelyabinsk (Ural), 12% from Yaroslavl

(central Russia), 4% from Astrakhan (southern Russia), and 3% from the Republic

of Buryatia (Siberia).

Participants were reached by email.

Every library had a unique link to the online questionnaire created on the

1ka.si survey platform. Participation was entirely voluntary and did not

involve any financial reward. Respondents were informed that, by completing the

survey, they were giving consent to their inclusion in the study. All ethical standards have been followed.

Table 1 demonstrates the descriptive

statistics of the sample. The mean participants’ age is 47.36 (the median age

is 49); the standard deviation equals to 11.91; range: 17-72. The majority of

the sample consists of females (95%). Most respondents have a higher education

degree (76%). Usually, the average

librarian has a bachelor’s degree; it is rare to have a master’s or a doctoral

degree among Russian librarians. In our sample, only 3% of the participants

have a master’s or doctoral degree. The average length of employment at the

current workplace equals 15.09 years (standard deviation = 12.47). Sixty-one

percent of the participants are from urban libraries, and 39% are from rural.

Measures

For measuring burnout, the Russian

version of the Burnout Assessment Tool (Schaufeli et

al., 2019) was used. It includes four subscales:

exhaustion (Cronbach’s α = .89, McDonald’s ω = .89), distance (Cronbach’s α =

.76, McDonald’s ω = .77), reduced emotional control (Cronbach’s α = .84,

McDonald’s ω = .85), and reduced cognitive control (Cronbach’s α = .85,

McDonald’s ω = .85). The response involves the five-point scale: 1 = Never, 5 =

Always. The Russian version of the burnout instrument was validated on

librarians of the Moscow region; the factorial validity (using confirmatory

factor analysis framework), convergent validity (correlations with optimism,

hardiness, and self-efficacy), and content validity were confirmed (Kolachev et al., 2019).

Age was measured in years. We also

included length of employment (in years) and type of library (0 = rural, 1 =

urban). Length of employment is an important predictor of burnout because less

experienced employees tend to burn out more (Dimunová

& Nagyová, 2012; Maslach et al., 2001). The

location of the library could be important because, in urban libraries, there

are more visitors than in rural ones; it produces more stress factors, which

leads to higher levels of burnout. For instance, according to Saijo et al. (2013), urban hospital physicians experience

higher levels of burnout than rural hospital physicians.

Additionally, we used the general self-efficacy scale

(Schwarzer

& Jerusalem, 1995). It is one of the

determinants of stress-related outcomes (Shoji et al., 2016). Moreover,

self-efficacy is a personal resource whose lower levels connect with higher

levels of burnout (Luthans, Avolio, Avey, & Norman, 2007). The instrument contains 10 items with the four-point response scale:

1 - Not at all true, 4 - Exactly true (Cronbach’s α = .91, McDonald’s ω = .91).

The scale was validated in many countries (Scholz, Doña,

Sud, & Schwarzer, 2002): the authors demonstrated factorial validity (using

confirmatory factor analysis framework), concurrent validity (correlations with

optimism, anxiety, social support), and measurement invariance (also using

confirmatory factor analysis framework).

Gender and education were not

included in the model due to little variation in these variables.

Data Analysis Plan

As a preliminary analysis, we performed confirmatory

factor analysis corrected for the clustered nature of the data to examine the

factor structure of the burnout measurement model before the structural model

was tested. The cluster correction is needed when the observations are nested

within clusters (in our case, librarians are nested within libraries).

Observations within clusters are more similar than between them (Hox, Moerbeek, & Van de Schoot, 2010). This implies that our observations are not

independent, which requires correction for non-independence.

The maximum likelihood estimation

with robust standard errors and a Satorra-Bentler

scaled test statistic (MLM) was used, which is appropriate for five-point

rating scales (Rhemtulla et al., 2012).

For observing connections of interest, structural

equation modeling with cluster correction was used. Structural equation

modeling is a useful technique because it estimates all parameters

simultaneously, including latent variables, and provides fit indices (Kline,

2011). Structural equation modeling incorporates measurement errors so that

researchers can get unbiased estimates of the effects between predictors and

outcomes (Bollen & Hoyle, 2012). Structural variables included age, length of

employment at the current workplace, library location, and self-efficacy

variables.

All statistical analysis was

performed in R version 3.6.1 (R Core Team, 2016) using such packages as lavaan (measurement and structural models; Rosseel, 2012), lavaan.survey

(cluster correction for the measurement and structural models; Oberski, 2014), and sjPlot

(correlational matrix; Lüdecke, 2018; Wickham,

2016).

The data described in this article are openly

available in CSV format in the Open Science Framework at https://osf.io/m7nwk/.

Results

For the confirmatory factor analysis,

the following indicators are the quality criteria: RMSEA < .08, CFI and TLI

> .90, SRMR < .08 (Kline, 2011). The model with four first-order factors

(exhaustion, distance, reduced emotional control, and reduced cognitive

control) was fitted; it was identified through fixing the variance of the

latent variables to 1. The results are the following: χ2 (224, N =

620) = 418.25, scaling factor = 1.31, CFI = .96, TLI = .96, RMSEA = .04 90% CI

[.04;.05], SRMR = .04. All factor loadings, except one, exceeded .60 and were

significant. Therefore, the measurement model demonstrated a good fit.

Table 2

Bivariate

Correlations of the Variables of Interest

|

Variable |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

|

1. Exhaustion |

|

|

|||||

|

2. Distance |

.65*** |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

3. Reduced emotional control |

.64*** |

.55*** |

|

|

|

|

|

|

4. Reduced cognitive control |

.59*** |

.63*** |

.61*** |

|

|

|

|

|

5. Age |

-.18*** |

-.17*** |

-.01 |

-.14*** |

|

|

|

|

6. Length of employment |

-.08* |

-.07 |

-.00 |

-.12** |

.60*** |

|

|

|

7. Library location (0 = rural, 1 = urban) |

.08* |

.13** |

.10* |

.03 |

-.05 |

-.08 |

|

|

8. Self-efficacy |

-.43*** |

-.42*** |

-.39*** |

-.46*** |

-.05 |

-.06 |

.01 |

Note. Computed correlation used the Spearman method.

* p < .05. ** p < .01.

*** p < .001.

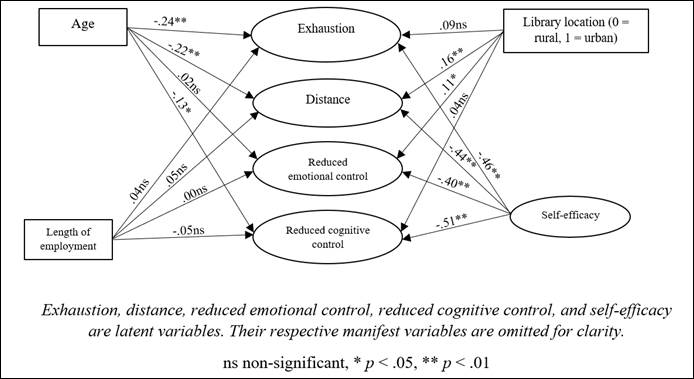

Figure 1

Structural equation model of

relations between age, length of employment, library location, self-efficacy,

and the factors of burnout (standardized solution; n = 620).

Table 2 depicts the bivariate

correlations between variables tested in the structural model. We can see that

burnout dimensions are highly interrelated and negatively correlate with

self-efficacy. Age significantly links to exhaustion, distance, and reduced

cognitive control. Length of employment correlates significantly with

exhaustion, reduced cognitive control, and age. Library location relates to

exhaustion, distance, and reduced emotional control. Also, age, length of

employment, and library location do not correlate with self-efficacy.

Structural Model

Figure 1 displays the paths and

coefficients of the tested model. First, authors tested the structural model of

the links between age and burnout symptoms controlling for length of

employment, library location, and self-efficacy.

Table 3 depicts standardized and unstandardized

regression coefficients. Unstandardized coefficients are estimates of

relationships in real units of measurement. Standardized coefficients are the

same as the correlation coefficients. Table 3 shows that the model fits the

data well because CFI and TLI > .90, RMSEA < .08, and SRMR < .08 (see

note in Table 3). Among all predictors, self-efficacy significantly predicts

each of the burnout dimensions, controlling for age, length of employment, and

library location. Age negatively links to exhaustion and distance. Also, age

predicts significantly reduced cognitive control. As in the bivariate

correlations demonstrated, age does not relate to reduced emotional control.

Length of employment does not predict any of the burnout factors. There is a

difference in distance and reduced emotional control between rural and urban

library workers: those who work at urban libraries have higher levels of

distance and a lower level of emotional control. Also, respondents from urban

libraries demonstrate higher levels of distance and greater problems with

emotional control compared to rural library workers. Although these differences

between urban and rural librarians are small. Predictors explained 27% of the

variance in exhaustion, 26% of the variance in distance, 17% of the variance in

reduced emotional control, and 29% of the variance in reduced cognitive control

dispersion.

Also, we conducted an additional

correlational analysis on the non-Moscow region part of the sample. We found

that exhaustion correlates negatively with age

(r = -.16, p = .02); there is a negative correlation between age

and distance (r = -.14, p = .04); age and impaired emotional

control are linked positively (r = .15, p = .03); there is no

significant correlation between age and impaired cognitive control (r =

.01, p = .93).

Discussion

In the present study, the main aim

was to examine how age relates to burnout components such as exhaustion,

distance, reduced emotional control, and reduced cognitive control in a

librarian sample. As predicted (H1), age

linearly and negatively links to exhaustion and distance. Contrary to the

predictions (H2), age does not relate to reduced emotional control.

Not in line with our expectations (H3), younger workers reported

greater problems with cognitive control at work compared to their older

colleagues. The length of employment did not predict any of the burnout

factors. In addition, there is a difference between rural and urban library

workers in mental distance and reduced emotional control. Urban librarians tend

to demonstrate higher levels of distance and have more reduced emotional

regulation than their rural counterparts.

Age more strongly predicts

exhaustion; therefore, younger employees are more likely to experience

emotional exhaustion. Younger librarians are also more prone to distance

themselves from work than their older counterparts. These results are in

correspondence with Salyers et al. (2019), who in a sample of librarians of the

Indiana State Library, found that emotional exhaustion and cynicism were

related negatively to burnout: r = -.19 and r = -.15,

respectively. In our sample, the correlation of exhaustion and age was -.18,

between distance (the same as cynicism) and age was -.17. Wood, Guimaraes, Holm, Hayes, and Brooks (2020), in a

sample of 1,628 academic librarians employed within the United States, found

that age was related to burnout significantly and negatively. However, Martini,

Viotti, Converso, Battaglia, and Loera (2019), in a

sample of 167 Italian public library workers, found that controlling for job

demands, job resources, and some demographic variables age was linked to

exhaustion positively while the link between age and cynicism was

insignificant.

Table 3

|

Unstandardized

Coefficients |

Standardized

Coefficients |

p |

|

|

Age → Exhaustion |

-0.02 (0.005) |

-.24 |

.00 |

|

Age → Distance |

-0.02 (0.006) |

-.22 |

.00 |

|

Age → Reduced emotional control |

0.00 (0.005) |

.02 |

.69 |

|

Age → Reduced cognitive control |

-0.01 (0.006) |

-.13 |

.03 |

|

Length of employment → Exhaustion |

0.00 (0.004) |

.04 |

.38 |

|

Length of employment → Distance |

0.005 (0.003) |

.05 |

.14 |

|

Length of employment → Reduced emotional control |

0.00 (0.004) |

-.00 |

.93 |

|

Length of employment → Reduced cognitive control |

-0.005 (0.005) |

-.05 |

.33 |

|

Library location → Exhaustion |

0.20 (0.14) |

.09 |

.14 |

|

Library location → Distance |

0.38 (0.11) |

.16 |

.00 |

|

Library location → Reduced emotional control |

0.26 (0.12) |

.11 |

.03 |

|

Library location → Reduced cognitive control |

0.09 (0.15) |

.04 |

.54 |

|

Self-efficacy → Exhaustion |

-0.53 (0.06) |

-.46 |

.00 |

|

Self-efficacy → Distance |

-0.51 (0.06) |

-.44 |

.00 |

|

Self-efficacy → Reduced emotional control |

-0.44 (0.05) |

-.40 |

.00 |

|

Self-efficacy → Reduced cognitive control |

-0.61 (0.06) |

-.51 |

.00 |

Note. χ2(572) = 1070.38, p < .001, scaling factor = 1.23; CFI = .94; TLI = .93; RMSEA = .04, 90% CI [.04, .05]; SRMR = .04.

Also, our results overlap Marchand et

al.’s (2018) findings partially. In Canadian employees of the private sector,

they found that age was linearly and negatively linked to cynicism (b = -0.12,

95% CI [-0.17, -0.07]). However, the authors found that age was non-linearly

related to exhaustion (cubic predictor was significant). Moreover, they

revealed that the relations are different for males and females, demonstrating

non-linear pattern with exhaustion and cynicism in women. In men, associations

were linear. A similar non-linear pattern of results in women was obtained by Ahola et al. (2008). Probably, their results are

attributable to the higher heterogeneity in terms of different professions of

the representative sample. Instead, Brewer and Shapard

(2004), in a meta-analysis dedicated to employees’ burnout, found that the mean

correlation between age and exhaustion was -.18, corrected for heterogeneity of

the sample equaled to -.23. Our results confirm linear relations of exhaustion,

distance (the same as cynicism), and impaired cognitive control with age.

The only study of Russian librarians

dedicated to burnout showed linear relations between age and composite burnout

accounting for gender, length of employment, personal resources, and library

location (Kolachev et al., 2019). However, in this

study, the authors did not pay attention to the relations between age and the

four factors of burnout. Although our sample partially overlaps the sample in Kolachev et al. (2019) in terms of regions, our data

include librarians from other regions. Moreover, our correlational analysis

conducted in librarians from regions other than Moscow revealed that there are

no differences between librarians from the Moscow region and librarians from

other regions in our sample in the correlation pattern of age with exhaustion

and distance. However, there is a difference in relations with reduced emotional

control: older librarians not from the Moscow region tend to report more

problems with emotional control than their younger colleagues. Also, in

non-Moscow region librarians, there is no age difference in reduced cognitive

control. This is another characteristic that differentiates the librarians of

the Moscow region.

Concerning reduced emotional control,

participants of different ages reported similar levels of emotional regulation.

The relationship between emotion, age, and burnout appears to be complex.

Several researchers suggest that older adults are more likely to suppress

affect and inhibit emotional responses due to increased cognitive complexity (McConatha & Huba, 1999;

Orgeta, 2009). However, modern studies mention the

role of culture in emotional expression. Sheldon et al. (2017) claimed that

Russian people tend to inhibit their emotions no matter whom they encounter –

themselves or their countrymen. Russians are more emotionally self-distanced

than their western counterparts and are less prone to reflect in the case of

experiencing negative situations (Grossmann & Kross,

2010). According to the results obtained on the non-Moscow region part of our

sample, older workers are more prone to experience problems with emotional

control. This could mean that for this population, the idea that older workers

are more successful in emotional regulation is applicable, but it requires

further investigation. These results contradict Mauno

et al.’s (2013) conclusions that older workers have better emotional regulation

in relation to negative feelings.

Regarding the relations of reduced

cognitive control and age, it can be assumed that, according to Socioemotional

Selectivity Theory, older people may pay little attention to negative stimuli

(Martins, Florjanczyk, Jackson, Gatz, & Mather,

2018). At the same time, younger respondents tend to focus on negative stimuli

that distract them during the work. The increased engagement with negative

information leads to more problems with cognitive control in younger workers.

Research conducted by Martins, Sheppes,

Gross, and Mather (2016) confirmed that older people become less

distracted when exposed to positive stimuli and more distracted when exposed to

negative ones. The non-Moscow region part of our sample

demonstrates an absence of the significant link between age and reduced

cognitive control. Potentially it could be another specific feature of the

non-Moscow region librarians and requires more empirical evidence.

Comparing the present

results with those obtained from studies of other professions demonstrates that

the relationship between age and burnout is complex and may be

situation-dependent. For instance, Thomas, Kohli, and Choi (2014), on a sample

of Californian human service workers, found that when controlling for education

and caseload size, age was a positive predictor of burnout (the standardized

regression coefficient was .18) while years of experience did not link to

burnout. However, Chou, Li, and Hu (2014), on a sample of the medical staff of

a hospital in Taiwan, revealed that older employees were less prone to

experience burnout. Therefore, it would appear that the relationship between

burnout and age may differ by profession.

The present findings have some

practical implications. It is of use to implement burnout screening in

personnel so that supervisors could propose some psychological or even medical

assistance to those who are at risk of burnout. There are national and European

laws and regulations that oblige employers to assess psychosocial risks among

their employees periodically and to implement policies to prevent burnout and

work stress (Schaufeli et al., 2019).

In several European countries, burnout is acknowledged as an occupational

disease or work-related disorder, and there is some compensation for workers

included in social insurance (Lastovkova et al.,

2017). In the context of librarianship, two directions can be distinguished.

First, it is essential to organize an annual program for monitoring employees’

emotional state in order to prevent attrition or reduced job performance. In

the absence of a specialized HR department, this program can be implemented by

library methodologists. Second, if alarming indicators of stress or burnout are

found, job rotation might be applied. For example, a service department

employee could work in the acquisition department. Caputo (1991) claims that

librarians would appreciate a work rotation that equitably distributes

unpopular tasks, such as a particularly heavy reference shift or equipment

service calls. Also, if possible, it could be beneficial to give some

professional and psychological guidance to newcomers so that they adapt

successfully to working conditions. For instance, as Smith, Bazalar, and

Wheeler (2020) point out, “pre-service librarians

might shadow a public librarian who works at the reference desk or a staff

member with administrative duties to get a first-hand glimpse into how to

navigate job duties” (p. 426-7).

Limitations

The current research is not free of

several limitations. First, the study included a voluntary sample of

participants, which means that the results may reflect self-selection bias.

This may lead to another explanation of the results by the phenomenon of the

survivor’s bias, since if older employees experience lower levels of burnout,

this may mean that only the most persistent and resilient ones have remained at

work (Maslach et al., 2001). Second, there are many potential explanations of

the results due to the absence of control for cohort differences. Cohort

differences may reflect different work attitudes and values. Finally, results

may not be generalizable; as data mostly came from libraries in the central

region of the Russian Federation, these librarians may differ from the rest of

the country, as we noticed differences concerning reduced emotional and reduced

cognitive control.

Conclusion

Despite the limitations mentioned

above, the current paper confirms some previous results on negative relations

between burnout symptoms and chronological age. This

study is a first attempt to scrutinize burnout in librarians using the

instrument based on a new burnout framework that better describes the

phenomenon. The results obtained indicate that young employees are at risk

not only for exhaustion and depersonalization at work but also for problems

with cognitive functions, in particular with attention. They may need

psychological help not only in terms of rest to diminish exhaustion and mental

distance but a strengthening of attentional skills. Also, in relation to the

aging workforce problem, the current study proposes a new challenge for the

management and human resources fields in librarianship: how to help young

workers experience less burnout or avoid it altogether? If we account for

self-reporting bias, it is of practical importance to maintain and boost

subjective well-being in younger employees. Moreover, the resilient potential

of older workers remains unclear and requires further investigation.

References

Adams, G. A. & Shultz, K. S. (2018). Introduction and Overview. In G.A.

Adams & K. S. Shultz (Eds.), Aging

and work in the 21st century (pp. 34-58). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315167602-1

Ahola, K., Honkonen, T.,

Virtanen, M., Aromaa, A., & Lönnqvist,

J. (2008). Burnout in relation to age in the adult working population. Journal of Occupational Health,

50(4), 362-365. https://doi.org/10.1539/joh.m8002

Bakker, A. B., & Demerouti, E. (2007). The Job

Demands-Resources model: State of the art. Journal

of Managerial Psychology, 22(3),

309–328. https://doi.org/10.1108/02683940710733115

Bianchi R. (2018). Burnout is more strongly linked to

neuroticism than to work-contextualized factors. Psychiatry Research, 270, 901-905. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2018.11.015

Bollen, K. A., & Hoyle, R. H. (2012). Latent

variables in structural equation modeling. In R. H. Hoyle (Ed.), Handbook

of structural equation modeling (p. 56-67). The Guilford Press.

Brewer, E. W., & Shapard,

L. (2004). Employee burnout: A meta-analysis of the relationship between age or

years of experience. Human resource development review, 3(2), 102-123. https://doi.org/10.1177/1534484304263335

Caputo, J. S. (1991). Stress and Burnout in Library

Service. Oryx Press.

Chou, L. P., Li, C. Y., & Hu, S. C. (2014). Job

stress and burnout in hospital employees: comparisons of different medical

professions in a regional hospital in Taiwan. B.M.J. Open, 4(2). https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2013-004185

Deary, I.J., Corley, J., Gow,

A.J., Harris, S.E., Houlihan, L.M., Marioni, R.E., Penke, L., Rafnsson, S.B., &

Starr, J.M. (2009). Age-associated cognitive decline. British Medical Bulletin, 92(1), 135-152. https://doi.org/10.1093/bmb/ldp033

Deligkaris, P., Panagopoulou,

E., Montgomery, A. J., & Masoura, E. (2014). Job

burnout and cognitive functioning: A systematic review. Work & Stress,

28(2), 107–123.

Diestel, S., Cosmar, M.,

& Schmidt, K. H. (2013). Burnout and impaired cognitive functioning: The

role of executive control in the performance of cognitive tasks. Work & Stress, 27(2), 164-180. https://doi.org/10.1080/02678373.2013.790243

Dimunová, L., & Nagyová, I.

(2012). The relationship between burnout and the length of work experience in

nurses and midwives in the Slovak Republic. Profese

Online, 5(1), 1-4. https://doi.org/10.5507/pol.2012.001

Doerwald, F., Scheibe, S., Zacher, H., & Van Yperen, N.

W. (2016). Emotional competencies across adulthood: State of knowledge and

implications for the work context. Work, Aging and

Retirement, 2(2), 159-216. https://doi.org/10.1093/workar/waw013

Eurostat. (2020). Employees by sex, age and occupation

(1,000). Retrieved from https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/lfsq_eegais/default/table?lang=en

Federal State Statistics Service.

(2019). Chislennost' postoyannogo

naseleniya na 1 yanvarya [Total population number as of January 1].

Retrieved from https://showdata.gks.ru/report/278928/

Federalniy zakon №78

“O bibliotechnom dele” [Federal Law №78 “On

librarianship”]. (1994 & Supp. 2019). Retrieved from http://www.consultant.ru/document/cons_doc_LAW_5434/c..

Grossmann, I., & Kross,

E. (2010). The impact of culture on adaptive versus maladaptive self-reflection.

Psychological Science, 21(8),

1150-1157. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797610376655

Hox, J. J., Moerbeek, M.,

& van de Schoot, R. (2010). Multilevel

analysis: Techniques and applications. Routledge.

Johnson, S. J., Machowski,

S., Holdsworth, L., Kern, M., & Zapf, D. (2017). Age, emotion regulation

strategies, burnout, and engagement in the service sector: Advantages of older

workers. Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 33(3), 205-216. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rpto.2017.09.001

Kline, R. B. (2011). Principles and practice of structural equation

modeling (3rd ed.). Guilford Press.

Kolachev, N., Osin., E., Schaufeli,

W., & Desart, S. (2019). Personal resources and

burnout: Evidence from a study among librarians of Moscow Region. Organizational

Psychology, 9(2), 129-147.

Lastovkova, A., Carder, M., Rasmussen, H. M., Sjoberg, L., de Groene, G. J., Sauni, R., Vevoda, J., Vevodova, S., Lasfargues, G., Svartengren, M., Varga, M., Colosio, C., & Pelclova, D. (2018). Burnout syndrome as an occupational

disease in the European Union: An exploratory study. Industrial Health, 56(2), 160-165. https://doi.org/10.2486/indhealth.2017-0132

Lüdecke, D. (2018). sjPlot: Data visualization for statistics in

social science. Retrieved from https://cran.r-project.org/package=sjPlot

Luthans, F., Avolio, B. J., Avey,

J. B., & Norman, S. M. (2007). Positive psychological capital: Measurement

and relationship with performance and satisfaction. Personnel Psychology, 60(3),

541-572. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.2007.00083.x

Marchand, A., Blanc, M. E., & Beauregard, N.

(2018). Do age and gender contribute to workers’ burnout symptoms? Occupational Medicine,

68(6),

405-411. https://doi.org/10.1093/occmed/kqy088

Martini, M., Viotti, S.,

Converso, D., Battaglia, J., & Loera, B. (2019). When social support by

patrons protects against burnout: A study among Italian public library workers.

Journal of Librarianship and Information Science, 51(4), 1091-1102. https://doi.org/10.1177/0961000618763716

Martins, B., Florjanczyk,

J., Jackson, N. J., Gatz, M., & Mather, M. (2018). Age differences in

emotion regulation effort: Pupil response distinguishes reappraisal and

distraction for older but not younger adults. Psychology

and Aging, 33(2), 338-349. https://doi.org/10.1037/pag0000227

Martins, B., Sheppes, G.,

Gross, J. J., & Mather, M. (2016). Age differences in emotion regulation

choice: Older adults use distraction less than younger adults in high-intensity

positive contexts. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B, 73(4), 603-611. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbw028

Maslach, C., Schaufeli, W. B., & Leiter, M. P.

(2001). Job burnout. Annual Review of Psychology, 52(1), 397-422. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.397

Mauno, S., Ruokolainen, M., &

Kinnunen, U. (2013). Does aging make employees more

resilient to job stress? Age as a moderator in the job stressor–well-being

relationship in three Finnish occupational samples. Aging & Mental Health,

17(4),

411-422. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2012.747077

McConatha, J. T., & Huba, H. M.

(1999). Primary, secondary, and emotional control across adulthood. Current Psychology, 18(2), 164-170.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-999-1025-z

McCormack, N., & Cotter, C. (2013). Managing burnout in the workplace: A guide for information professionals. Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-1-84334-734-7.50010-4

McManus, I. C., Keeling, A., & Paice,

E. (2004). Stress, burnout and doctors’ attitudes to work are determined by

personality and learning style: A twelve year longitudinal

study of UK medical graduates. BMC Medicine, 2, 29. https://doi.org/10.1186/1741-7015-2-29

Murman, D. L. (2015). The impact of age on

cognition. Seminars in Hearing, 36(3), 111-121. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0035-1555115

National Library of Russia. (2020). Yezhegodnyy doklad o sostoyanii seti obshchedostupnykh bibliotek Rossiyskoy Federatsii: po itogam monitoringa 2019 g.

[Annual report on the state of the network of public libraries in the Russian

Federation: Based on the results of monitoring in 2019]. Retrieved from http://clrf.nlr.ru/images/SiteDocum/News/2020/ed_set_bibliotek_19.pdf

Oberski, D. (2014). lavaan. survey:

An R package for complex survey analysis of structural equation models. Journal of Statistical Software,

57(1), 1-27. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v057.i01

Orgeta, V. (2009). Specificity of age differences in emotion

regulation. Aging and Mental Health, 13(6), 818-826. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607860902989661

Penz, M., Wekenborg, M. K.,

Pieper, L., Beesdo‐Baum, K., Walther, A., Miller, R.,

Stadler, T., & Kirschbaum, C. (2018). The Dresden

Burnout Study: Protocol of a prospective cohort study for the bio‐psychological

investigation of burnout. International Journal of

Methods in Psychiatric Research,

27(2), e1613.

https://doi.org/10.1002/mpr.1613

R Core Team. (2016). R: A language and

environment for statistical computing. Retrieved from https://www.R-project.org/

Randall, K. J. (2007). Examining the relationship between burnout and

age among Anglican clergy in England and Wales. Mental Health, Religion

& Culture, 10(1), 39-46. https://doi.org/10.1080/13674670601012303

Rhemtulla, M.,

Brosseau-Liard, P. É., Savalei, V. (2012). When can

categorical variables be treated as continuous? A comparison of robust

continuous and categorical SEM estimation methods under suboptimal conditions. Psychological

Methods, 17(3), 354-373. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0029315

Rosseel, Y. (2012). lavaan:

An R Package for Structural Equation Modeling. Journal of Statistical

Software, 48(2), 1-36. http://dx.doi.org/10.18637/jss.v048.i02

Russian State Library. (2020). Kratkaya statisticheskaya spravka o Rossiyskoy gosudarstvennoy biblioteke v 2019

godu (po sostoyaniyu na 01.01.2020) [Brief statistical information about the

Russian State Library in 2019 (as of 01.01.2020). Retrieved from https://www.rsl.ru/ru/about/documents/statisticheskaya-spravka-o-rabote-rgb/spravka-2019

Saijo, Y., Chiba, S., Yoshioka, E., Kawanishi,

Y., Nakagi, Y., Ito, T., Sugioka, Y., Kitaoka-Higashiguchi, K., & Yoshida, T. (2013). Job

stress and burnout among urban and rural hospital physicians in Japan. The Australian Journal of Rural

Health, 21(4), 225-231. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajr.12040

Salyers, M. P., Watkins, M. A., Painter, A., Snajdr, E. A., Gilmer, L.

O., Garabrant, J. M., & Henry, N. H. (2019).

Predictors of burnout in public library employees. Journal of Librarianship and Information Science, 51(4), 974-983. https://doi.org/10.1177/0961000618759415

Schaufeli, W.B., De Witte, H. & Desart, S.

(2019). Manual Burnout Assessment Tool (BAT). KU Leuven, Belgium: Unpublished

internal report.

Scholz, U., Doña, B. G., Sud, S., & Schwarzer, R.

(2002). Is general self-efficacy a universal construct? Psychometric findings

from 25 countries. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 18(3),

242-251. https://doi.org/10.1027/1015-5759.18.3.242

Schwarzer, R., & Jerusalem, M. (1995). Generalized Self-Efficacy scale.

In J. Weinman, S. Wright, & M. Johnston (Eds.), Measures in health

psychology: A user’s portfolio. (pp. 35-37). NFER-NELSON.

Sheldon, K. M., Titova, L.,

Gordeeva, T. O., Osin, E. N., Lyubomirsky, S., & Bogomaz, S. (2017). Russians inhibit the expression of

happiness to strangers: Testing a display rule model. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 48(5),

718-733. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022117699883

Shoji, K., Cieslak, R., Smoktunowicz, E., Rogala, A.,

Benight, C. C., & Luszczynska, A. (2016).

Associations between job burnout and self-efficacy: A meta-analysis. Anxiety, Stress, & Coping,

29(4),

367-386. https://doi.org/10.1080/10615806.2015.1058369

Smith, N. M., & Nelson, V. C. (1983). Burnout: A

survey of academic reference librarians (Research Note). College & Research Libraries,

44(3),

245-250. https://doi.org/10.5860/crl_44_03_245

Smith, D. L., Bazalar,

B., & Wheeler, M. (2020). Public librarian job stressors and burnout

predictors. Journal of Library Administration, 60(4), 412-429. https://doi.org/10.1080/01930826.2020.1733347

Statistics Canada. (2019). Study: Occupations with

older workers. Retrieved from https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/en/daily-quotidien/190725/dq190725b-eng.pdf?st=UGDkvR71

Thomas, M., Kohli, V., & Choi, J. (2014).

Correlates of job burnout among human services workers: Implications for

workforce retention. The Journal

of Sociology and Social Welfare, 41(4),

69-90. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/jssw/vol41/iss4/5

Wickham, H. (2016). ggplot2: Elegant graphics for data analysis (2nd ed.). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-24277-4_9

Wilder, S. (2018). Delayed retirements and the youth

movement among ARL library professionals. Research

Library Issues, 295, 6-16.

https://doi.org/10.29242/rli.295.2

Wood, B. A., Guimaraes, A. B., Holm, C. E., Hayes, S.

W., & Brooks, K. R. (2020). Academic librarian burnout: A survey using the

Copenhagen Burnout Inventory (CBI). Journal of

Library Administration, 60(5), 512-531. https://doi.org/10.1080/01930826.2020.1729622

Xanthopoulou, D., Bakker, A. B., Demerouti, E., & Schaufeli,

W. B. (2007). The role of personal resources in the job demands-resources

model. International Journal of Stress Management, 14(2), 121-141. https://doi.org/10.1037/1072-5245.14.2.121

Zverevich, V. (2014). Developing the library

network in postcommunist Russia: Trends, issues, and

perspectives. Library Trends, 63(2), 144-160. https://doi.org/10.1353/lib.2014.0039