Review Article

Textbook Alternative Incentive Programs at U.S.

Universities: A Review of the Literature

Ashley Lierman

Instruction & Education

Librarian

Campbell Library

Rowan University

Glassboro, New Jersey,

United States of America

Email: lierman@rowan.edu

Received: 27 Mar. 2020 Accepted: 9 Sept. 2020

![]() 2020 Lierman. This is an Open

Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

2020 Lierman. This is an Open

Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

DOI: 10.18438/eblip29758

Abstract

Objective

–

This article reviews current literature on incentive grant programs for

textbook alternatives at universities and their libraries. Of particular

interest in this review are common patterns and factors in the design,

development, and implementation of these initiatives at the programmatic level,

trends in the results of assessment of programs, and unique elements of certain

institutions’ programs.

Methods

–

The review was limited in scope to

studies in scholarly and professional publications of textbook alternative

incentive programs at universities within the United States of America,

published within ten years prior to the investigation. A comprehensive

literature search was conducted and then subjected to analysis for trends and

patterns.

Results

–

Studies of these types of programs have

reported substantial total cost savings to affected students compared to the

relatively small financial investments that are required to establish them. The

majority of incentive programs were led by university libraries, although the

most successful efforts appear to have been broadly collaborative in nature.

Programs are well-regarded by students and faculty, with benefits to pedagogy

and access to materials beyond the cost savings to students. The field of

replacing textbooks with alternatives is still evolving, however, and the

required investment of faculty time and effort is still a barrier, while

inconsistent approaches to impact measurement make it difficult to compare

programs or establish best practices.

Conclusion

–

Overall, the literature shows evidence

of significant benefits from incentive programs at a relatively low cost.

Furthermore, these programs are opportunities to establish cross-campus

partnerships and collaborations, and collaboration seems to be effective at

helping to reduce barriers and increase impact. Further research is needed on

similar programs at community colleges and at higher education institutions

internationally.

Introduction

The cost of textbooks is prohibitive for

many postsecondary students. The National Center for Education Statistics found

that for the 2016–17 academic year, the average cost of books and supplies for

entering full-time undergraduate students at four-year institutions was $1,263,

almost 10% of the average cost of tuition (National Center for Education

Statistics, 2017). While textbook prices are no longer rising as quickly as

they were in the earliest part of the 21st century, in part due to

institutional efforts to make lower-cost options available (Levitan, 2018),

providing relief from textbook costs is still a major concern for student

success and college affordability. This is particularly true since high

textbook costs have been shown to prevent students from acquiring needed

materials for the academic curriculum (Senack, 2014).

One of the ways that colleges and

universities have responded to this issue is by encouraging faculty to replace

traditional course textbooks with materials that are available to students at

no additional cost. These may include resources that are owned by the

institution’s library or open educational resources (OER). OER are commonly

defined as educational resources, most often but not always available digitally

and online, that are both free of cost and freely available for use,

adaptation, and redistribution (Wiley et al., 2014). Both of these types of resources,

however, tend to be less centralized and marketed to faculty than traditional

textbooks, and faculty feedback has indicated that the cost of time and labour

associated with creating, adapting, implementing, or even simply locating those

that are appropriate can be substantial (Bell, 2012; Delimont

et al., 2016; Batchelor, 2018). Belikov & Bodily

(2016) have identified other significant barriers to faculty adoption of OER

specifically, most notably lack of information on OER, lack of discoverability

of OER, and confusion over the distinctions between OER and other types of

resources.

To overcome these barriers, over the

past decade, a growing number of postsecondary institutions have begun to offer

faculty small financial incentives to encourage the use or development of

textbook alternatives. Typically, these initiatives take the form of a small

grant program where faculty apply and agree to certain requirements, a body

within the institution evaluates their proposals, and a certain number of

applicants are awarded some type of financial remuneration for the effort that

their implementation of an alternative will entail. After their courses have

been taught, participating faculty may be required to report out on their

experiences, participate in later assessment efforts, or do both.

Aims

The aims of the present work are to

conduct a narrative review of the professional and scholarly literature

specifically on incentive grant programs for textbook alternatives and to seek

out themes and commonalities in the experiences of the authors and other

participants. Key items to investigate include common patterns and factors in

the design, development, and implementation of these initiatives at the

programmatic level, trends in the results of assessment of programs, and unique

elements of certain institutions’ programs and what impact they appear to have

had. Finally, conclusions and recommendations are drawn from the literature

that may be used to inform developers and maintainers of similar programs in

the future.

Methods

The first step in the process of

gathering literature for this review was establishing a general scope for

inclusion. While community colleges have developed a significant number of

textbook alternative incentive programs, these programs differ significantly in

implementation from those at four-year colleges and universities, and the

latter is the focus of this present study. Similarly, many more incentive

programs exist or have existed than those discussed here, but the set of cases

to follow includes only those that have been presented in the literature to

maximize the narrative description, reflection, and assessment data that are

available. The scope of this work is also limited to studies of full incentive

programs not individual course implementations or specific resources.

Additionally, in recognition of the significant international differences

around issues of OER and college affordability, I have considered here only

studies of institutions from the United States. A comparison of global trends

in OER implementations and incentives in higher education would be a valuable

direction for future study but is not the aim of the present work.

With these foci in mind, I constructed

and ran a search in five databases: Educational Resources Information Center,

or ERIC; Education Source (EBSCO); Educational Administration Abstracts;

Library Literature & Information Science Full Text (H.W. Wilson); and

Library, Information Science & Technology Abstracts, or LISTA. I selected

this set of databases because it comprises those available to me with the most

significant literature coverage in education and in library and information

science, with multiple databases included in each area to increase

comprehensiveness. The search included results published since 2010 that

contained variants of the terms "affordable,"

"alternative," or "replace" anywhere, contained variants of

the terms "program" or "initiative" or "fund" or

"grant" anywhere, and contained variants of the term

"textbook" specifically in the title or subject terms. The term

"open" was originally included in the first set of terms, but it

returned too many irrelevant results simply concerning the development of

individual open textbooks and did not significantly increase the relevant

results over the other terms and as such was ultimately eliminated.

When initially conducted, the search

retrieved 152 results, of which approximately 30 were selected. I reviewed and

weeded these initial 30 results for their relevance to the scope stated

previously and reviewed the bibliographic references of each work for

additional relevant publications that the original search might have missed.

The search also included using the directory of institutions available from

SPARC's Connect OER site to identify institutions with financial incentive

programs for materials replacement and searching the names of these individual

institutions along with variants of the word "textbook" across

multiple library and information science databases. In this stage, the search

specifically focused on library and information science databases because of

SPARC's large academic library membership. After this stage, the results

underwent a similar process of review, weeding, and citation mining.

Additional criteria for inclusion and exclusion

emerged and were applied after this process to further narrow the results.

Sources were included only if they described the development of the program,

the assessment of the program, or both in enough detail to answer most of the

following questions:

- Who on campus led or leads the program?

- When and how did it begin?

- What were the steps taken to begin the program?

- Who were the partners on- and off-campus?

- From where did funding come?

- What was the total funding and how much was

awarded to each recipient?

- What were the application requirements?

- How many applications have there been?

- What was assessed?

- What were the results?

- What strategies have been considered to

increase the impact of the program?

I selected these questions for their

particular importance to campus stakeholders who would be responsible for the

creation of an incentive program and who would be most interested in knowing

what results such a program might produce. Sources were excluded if

insufficient detail about the formation or assessment of the program was

provided to answer most of these questions. For example, cases where an

incentive program was discussed briefly as part of a broad description of

campus OER efforts were omitted. Some sources were also excluded because their

primary focus appeared to be the creation of an OER publishing platform that

happened to be incentivized by grants rather than focusing on replacing

textbooks and reducing course costs through the incentive program. Studies

focusing more on the content, delivery systems, or pedagogical value of

textbook alternatives than on the development and functioning of an incentive

program were likewise considered to be out of scope, unless they were connected

to a program on which other, more general studies were available.

After establishing a final list of remaining studies had been, I took extensive

notes on any description of the development and assessment of programs that had

been included and analyzed the results for trends and recurring themes across

institutions. Specifically, the answers to each question identified previously

were compared across institutions and coded into commonly recurring categories

or noted as unique. Where no answer was found in the literature to a question

for a given institution, more information was sought on the website and other

publicly available materials of the institution's textbook alternative program.

If no information could be found by consulting these materials, the answer to

that question was noted as "not stated."

Results

Table 1 provides the U.S. institutions

included in this review, with the years that their textbook alternative

incentive programs began. (Some of the institutions listed established these

initiatives as part of a larger program for textbook affordability, but the

date provided is the date that the incentive program, specifically, began.)

Leaders

and Partners

In the studies examined, program leaders

have overwhelmingly been university libraries or library systems. Where

libraries were not the sole program leaders, programs were instead led by

campus-wide committees that included library representatives; libraries were

represented in the leadership of all programs considered. In most cases,

however, on- or off-campus partners have also supported programs in conjunction

with libraries. Table 2 identifies the leadership and additional partners of

each included institution.

University bookstores were, by a narrow

margin, the most common partner on textbook alternative incentive programs.

This seems surprising given bookstores' presumed interest in the continued sale

of traditional textbooks. While Agee and Mune (2014)

note the apparent strangeness of such partnerships, they claim that most

university bookstores now rely on the revenue streams from other merchandise

more than that of textbooks and tend to find that the goodwill generated by

collaborating on textbook affordability outweighs the revenue lost by

decreasing textbook sales (p. 18).

Table 1

Institutions

and Start Dates of Their Textbook Alternative Incentive Programs

|

Start date |

Institution(s) |

|

2010 |

Temple

University |

|

2011 |

University

of Massachusetts-Amherst |

|

2013 |

North

Carolina State University Kansas

State University University

of California, Los Angeles San

Jose State University |

|

2014 |

University

of Oklahoma |

|

2015 |

University

System of Georgia East

Carolina University & University of North Carolina-Greensboro (joint

collaboration) University

of Texas at San Antonio |

|

2016 |

Rutgers

University University

of Washington Florida

State University University

of North Dakota |

Table 2

Participants

in Textbook Alternative Incentive Programs by Institution

|

Institution |

Program

leader(s) |

Other

partners on program |

|

Temple University |

Library |

None |

|

University of Massachusetts-Amherst |

Library |

Faculty centre OpenStax Open Textbook Network Provost's office |

|

North Carolina State University |

Library |

University bookstore |

|

Kansas State University |

Collaborative university-wide faculty

team, including library representatives |

Student government University administration University senate |

|

UCLA |

Library |

California Digital Library Student government University bookstore University senate University system administration |

|

San Jose State University |

Library |

Faculty centre University bookstore University system administration |

|

University of Oklahoma |

Library |

College of Arts and Sciences College of Business Faculty centre OpenStax Open Textbook Network |

|

University System of Georgia |

Libraries network |

GALILEO (virtual library project) Online core curriculum leadership OpenStax State of Georgia University presses |

|

East Carolina University &

University of North Carolina-Greensboro |

Libraries |

Provost's office University bookstore |

|

University of Texas at San Antonio |

Library |

Faculty centre OpenStax Registrar Student government University bookstore |

|

Rutgers University |

Library |

Student section of NJPIRG (public

interest research group) |

|

University of Washington |

Library |

Friends of the UW Library organization Open Textbook Network Rebus Foundation |

|

Florida State University |

Library |

None |

|

University of North Dakota |

University-wide committee chaired by

library and provost representatives |

Faculty Student government Technology and instruction centres |

Funding

and Awards

Numerical comparisons of incentive

programs based on the literature are not necessarily definitive due to

differences in measurement strategies, lengths of assessment periods, and other

factors between studies. Nonetheless, a few rough patterns do emerge on

comparison of funding sources, total amounts, and amounts per award by program.

Table 3 shows this information (where available) for the represented institutions.

Library budgets were the most common

source of funds (where stated) by a significant margin, while various grant

sources from within or without the university system were also relatively

common. No individual program described investing more than $60,000 total in

incentive grants, and most total funding pools were somewhere between $10,000

and $40,000, with a substantial number also totaling less than $10,000. Some

institutions opted for a flat amount for individual awards, while others used tiered

funding distributions that provided larger incentives to faculty teaching

higher-enrolment or higher-impact courses. In either case, only one program

offered award amounts of less than $500 and only one offered amounts of more

than $5000, and for the minimum award amount was most commonly between $500 and

$1000.

Table 3

Funding and

Awards for Textbook Alternative Incentive Programs by Institution

|

Institution |

Funding

source |

Total

funding pool |

Amount

per award |

|

Temple University |

Library budget |

Not stated |

$1000 |

|

University of Massachusetts-Amherst |

Library budget Provost |

$10,000 |

$1000 for smaller classes $2500 for larger classes |

|

North Carolina State University |

Not stated |

Not stated |

Between $500 and $2000 |

|

Kansas State University |

University grant Library budget Administration (later) |

$60,000 (first round) $40,000 (second round) $50,000 (administration funding) |

Not stated |

|

UCLA |

Library budget University system grant Campus partners |

$27,500 |

$1000 for courses under 200 enrolment $2500 for courses over 200 enrolment |

|

San Jose State University |

University system grant |

$20,000 (first round) $49,000 (second round) |

$500–$2000 (first round) $1000 (second round) $1500 (final) |

|

University of Oklahoma |

Not stated |

$9600 (pilot) |

$1200–$2500 (pilot) $250–$2500 (second year) |

|

University System of Georgia |

State budget |

Not stated |

Up to $10,800 for courses under 500

enrolment Up to $30,000 for courses over 500

enrolment |

|

East Carolina University &

University of North Carolina-Greensboro |

Library budget Provost State grant |

$10,000 (pilot) Not stated for grant phase |

$1000 |

|

University of Texas at San Antonio |

Library budget |

$7500 |

$1500 |

|

Rutgers University |

Library budget Donor funding |

Not stated |

$500 - $1000 |

|

University of Washington |

Friends of the Library grant |

$4500 |

$1500 |

|

Florida State University |

Library budget |

$6000 |

$1000 |

|

University of North Dakota |

Local foundation Library donor fund |

$25,000 (partially for non-incentive

costs) |

$3000 |

Table 4

Applicants and

Requirements for Textbook Alternative Incentive Programs by Institution

|

Institution |

Total

applicants |

Accepted

applicants |

Grant

requirements |

|

Temple University |

11 |

11 |

Proposal only |

|

University of Massachusetts-Amherst |

8 |

8 |

Workshop attendance Assessment Syllabus submission Repository deposit of materials Final report |

|

North Carolina State University |

Not stated |

Not stated; 20 total courses |

Application only |

|

Kansas State University |

14 |

12 |

Application only |

|

UCLA |

27 |

Not stated |

Workshop attendance |

|

San Jose State University |

23 |

Not stated; 25 total sections in first

round |

Workshop attendance Syllabus submission |

|

University of Oklahoma |

Not stated |

5 |

Application only |

|

University System of Georgia |

Not stated |

29+ in round 1 |

Assessment Sustainability measures Open access to materials Final report Peer review (highest level) |

|

East Carolina University &

University of North Carolina-Greensboro |

22 (pilot) Not stated (grant phase) |

10 (pilot) 38 (grant phase) |

Meet with librarian |

|

University of Texas at San Antonio |

11 (first round) 33 (second round) |

5 (first round) Not stated (second round) |

Application only |

|

Rutgers University |

Not stated |

32 (first round) 57 (by time of writing) |

Assessment Syllabus submission |

|

University of Washington |

3 |

2 |

Proposal only |

|

Florida State University |

7 |

6 |

Memo. of understanding Workshop attendance Meet with librarian |

|

University of North Dakota |

2 |

2 |

Workshop attendance Meet with librarian |

Applicants

and Requirements

Most programs appear to have had

relatively few applicants and awardees, where numbers were provided, with

almost all having fewer than 30 total applicants and several having fewer than

10. A majority of programs also accepted a relatively high percentage of their

applicants, with a significant majority either accepting all applicants or

accepting more than two-thirds of the total pool. Only two programs that

provided application and acceptance statistics accepted fewer than 50% of those

who applied. By a narrow margin, the majority of programs also required only an

application or proposal, but other common requirements were for faculty to

attend a workshop on implementing textbook alternatives, to submit a proposed

syllabus revisions incorporating the replacement materials, to participate in

some form of assessment of the program, to meet with a librarian for support,

to submit a final report on their project, or to make any modified or created

materials available openly in kind either via the institutional repository or

otherwise. Applications for the University System of Georgia’s grants were also

required to describe the measures they intended to take for sustainability, and

applications for the largest and most far-reaching award type (aimed at

textbook replacements affecting entire departments or institutions) were

required to undergo double-blind peer review (Gallant, 2015).

Table 4 provides the number of

applicants to each program, the number that were accepted and funded, and what

was required of faculty to apply for a grant where each was stated.

Student

Impact and Cost Savings

As mentioned in the section on funding

and awards, comparing the numbers of students impacted or their cost savings

across multiple institutions is difficult since not all institutions measured

comparable spans to one another, and the time frame or calculation formula used

for a reported figure is not always clear. Rough categories of impact do emerge

from the literature, but these are not necessarily accurate representations of

the current state of these programs. Table 5 provides the reported estimates of

students impacted and cost savings by programs where these were given.

With regard to the figure stated for the

University System of Georgia, it should be noted that Croteau (2017) gives the

figure for the first round of grants as $760,000, which does not seem compatible

with the $9 million figure provided by Gallant (2015). This may be due to a

difference in calculation methods between the two authors, as the formulae in

use are unclear. Given the amount of the system’s grants, its state support,

and affiliated efforts to eliminate materials costs for online courses across

the system, however, it is also not impossible for the cost savings to have

increased to this degree over time.

Most studies that reported numbers of

students impacted indicated that their programs had affected fewer than 2000

students—relatively few, given the enrolment numbers for most of these

institutions. Many of these studies were, however, reporting on pilot programs,

and presumably future efforts would seek to expand their scope of impact.

Moreover, in those instances where both an initial total investment amount and

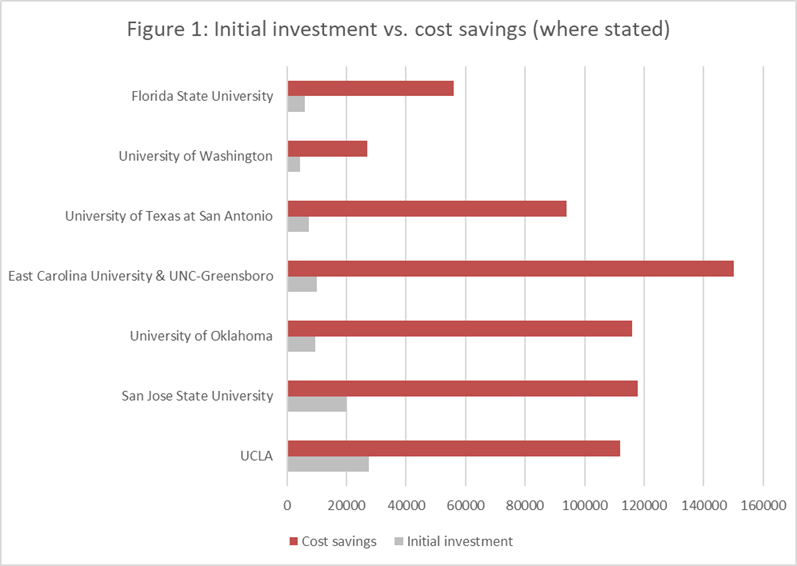

an estimation of cost savings were included, the difference of the two was

generally substantial. Figure 1 shows the initial investment and cost savings

by institution where stated.

An important caveat when comparing these

numbers is the point that student cost savings are not calculated identically

by each institution. The most commonly cited method of calculating cost savings

was to multiply the cost of course materials before and after program

participation by the number of enrolled students and subtract the latter from

the former, but precise applications of this formula varied. At Florida State,

for example, this formula was used with an estimated average of students

enrolled annually in the courses in question (Soper et al., 2018), while UCLA

and UMass-Amherst used actual observed enrolment numbers but estimated the

costs of course materials (Smith, 2018; Farb & Grappone, 2014). Reporting on the program at San Jose State

included both estimated and actual savings. The former was calculated based on

the estimated number of students or the enrolment cap and the list price of

previously used materials and the latter based on the actual observed total cost

of course materials and number of students who actually enrolled (Bailey &

Poo, 2018). At the University of Oklahoma, potential cost savings were

calculated in advance for purposes of evaluating proposals, using a similar

formula of projected enrolment multiplied by original and reduced costs of

materials, but it unclear whether this was also how the final cost savings were

calculated (Waller et al., 2018). A number of other studies provided no formula

for their cost estimates at all, and descriptions of the programs at UT San

Antonio and the University of Washington stated only that cost savings were

calculated by their partners at OpenStax or the Open Textbook Network (Ivie & Ellis, 2018; Batchelor,

2018).

Table 5

Students

Impacted and Cost Savings from Textbook Alternative Programs by Institution

|

Institution |

Estimated

students impacted |

Estimated

cost savings |

|

Temple University |

Not stated |

Not stated |

|

University of Massachusetts-Amherst |

1600 (2011–2015) |

$101,632 (2011–2015) |

|

North Carolina State University |

Not stated |

$250,000 |

|

Kansas State University |

10,941 (2015–16) 17,963 (first two years total) |

$921,000 (2015–16) $1.61 million (first two years total) |

|

UCLA |

Over 1000 |

$112,000 |

|

San Jose State University |

777 (first round) |

$117,739 (first round) |

|

University of Oklahoma |

420 (pilot) |

$116,000 (pilot) $274,000 (second year, first semester) |

|

University System of Georgia |

Not stated |

$9 million (first two rounds) |

|

East Carolina University &

University of North Carolina-Greensboro |

Not stated (pilot) 3300 total

(grant phase) |

$150,120 (pilot) $547,000 total (grant phase) |

|

University of Texas at San Antonio |

568 |

$94,000 |

|

Rutgers University |

9000 |

Over $2 million |

|

University of Washington |

180 |

$27,000 |

|

Florida State University |

Not stated |

$56,000 |

|

University of North Dakota |

Not stated |

$3.7 million maximum (two years) |

Figure

1

Initial

investment versus cost savings (where stated).

Further complicating the matter, several

authors suggested that student cost savings may be lower than the estimations

because of methods that students commonly use to acquire textbooks for less

than what the texts would cost if purchased new, such as rentals, buying used

texts, using older editions, and similar methods (Lashley et al., 2017; Walker,

2018; Todorinova & Wilkinson, 2019). Kansas State

program evaluators even attempted to compensate for this consideration in their

calculation formula for student cost savings by using the actual cost of

textbooks in their calculations only if they would have cost under $100 and

using $100 as a flat cost for any texts costing $100 or more (Lashley et al.,

2017). The study at the University of North Dakota simply acknowledged that its

calculation using original new textbook costs multiplied by enrolment numbers

represents a maximum possible cost savings to students from the program and

that the real impact was most likely lower (Walker, 2018).

Other

Trends in Assessment

Student impact and cost savings were the

most commonly assessed data from incentive programs, but a number of programs

also included assessment of other factors. In several studies, student academic

performance was measured before and after the implementation of textbook

alternatives, and in all cases performance was found

to be the same or better afterward (Smith, 2018; Croteau, 2017; Thomas &

Bernhardt, 2018). Furthermore, Grimaldi, Mallick, Waters, and Baraniuk (2019) have pointed out that measures of textbook

alternatives’ impact on student learning to date have probably underrepresented

the benefits because the measures examine the difference in performance of all

students in the course and not only the students who could not otherwise have

afforded access to the textbooks, which does not accurately represent where the

impact on learning should be expected.

Table 6

Results of

Student Feedback on Textbook Alternative Programs by Institution

|

Institution |

Positives

noted by students |

Negatives

noted by students |

|

Temple University |

Cost savings |

Preference for print |

|

Kansas State University |

Cost savings Ease of access Customization |

Preference for print Dislike of specific replacements used |

|

UCLA |

Cost savings |

Not stated |

|

University of Texas at San Antonio |

Accessibility Ease of use |

Not stated |

|

Rutgers University |

Cost savings Ease of use |

Difficulty in notetaking and

collaboration |

Table 7

Results of Faculty Feedback on Textbook Alternative

Programs by Institution

|

Institution |

Positives

noted by faculty |

Negatives

noted by faculty |

|

Temple University |

Cost savings to students Increased student access Ability to customize & update |

Time investment |

|

North Carolina State University |

Improved teaching |

Not stated |

|

Kansas State University |

Cost savings to students Improved teaching Ability to customize & update Perceived student satisfaction |

Time investment Technological issues Copyright challenges |

|

UCLA |

Improved teaching |

Not stated |

|

University System of Georgia |

Improved teaching |

Not stated |

|

University of Texas at San Antonio |

Improved teaching |

Quality concerns |

|

University of Washington |

Improved teaching Ability to customize & update |

Time investment Quality concerns |

Beyond performance measures, both

faculty and student feedback on textbook alternative incentive programs was

overwhelmingly positive at all institutions where it was collected. Tables 6

and 7 detail specific positives and negatives noted in student and faculty

feedback, respectively, for those programs where it was collected.

It is also of note that when students

were asked to evaluate the quality of the materials they were provided in lieu

of textbooks at University System of Georgia institutions, the principal

finding was that students were not effective evaluators of resource quality,

and their estimations were disproportionately swayed by superficial factors

like visual appearance (Croteau, 2017).

Identified

Challenges

Some authors identified major challenges

in implementing their institutions’ programs. As suggested previously, one of

the most commonly recurring challenges was the amount of time and effort that

implementation required for participating faculty, and some program organizers

observed a need for increased recognition of faculty efforts in this area with

regard to tenure and other professional advancement decisions (Agee & Mune, 2014; Delimont et al.,

2016; Bazeley et al., 2019). The need for relevant

faculty training and support was also widely recognized, and faculty feedback

at some institutions indicated that more support was needed than had been

provided (Bailey & Poo, 2018; Young, 2016; Delimont

et al., 2016; Subramony, 2018).

Strategies

for Sustainability and Increasing Impact

Many of the programs discussed in the

literature were in early stages or pilot versions at the time of writing, and

few were in a position to discuss any sustainability planning or outcomes

specifically. Most authors, however, at least discussed future directions for

the program in question, the majority of which focused on increasing the

program's impact. These strategies could be said to be a means of planning for

sustainability in themselves, as the greater the program's apparent success the

greater the likelihood of continued funding and labor to support it.

The most common planned strategies for

ensuring sustainability and increasing the impact of programs were targeting

courses with particularly high enrolment or with high course costs or both and

working to increase collaboration with additional partners across campus,

particularly faculty and other units. Table 8 lists the planned strategies for

increasing impact for the institutional programs where they were given.

Unique

Program Elements

While some common trends can be observed

across multiple institutions, there are a few programs with unique and notable

elements in their design, implementation, or context. The University System of

Georgia’s Textbook Transformation Grants program, for example, clearly

represents something of a standout case among those described as it spans a

full system of state institutions, is funded at the state level, and provides

awards that are closer to full grants than the micro-grant models used at other

universities. It is also unusual because, while other programs offer tiered

awards based on enrolment numbers, the Textbook Transformation Grants program

actually offers four different grant types based on type of alternative

implementation: one for faculty simply using OER or other resources with no

cost to students; one for faculty using open textbooks produced by the initiative

OpenStax with whom the program is partnered; one for faculty creating course

packs sourced from library resources in partnership with a librarian; and one

for large-scale transformations of multiple courses, a department, an

institution, or multiple institutions (Croteau, 2017). At the same time, the

last funding level would surely not be possible without state-level support for

the program and the possibility of relatively large awards. Similarly, UCLA and

San Jose State were both able to develop relatively large funding pools and

disburse relatively high numbers of awards in large part due to investment in

their programs from the state level (Farb & Grappone, 2014; Bailey & Poo, 2018). When local

governments invest in the affordability of higher education in this manner,

there does seem to be an impact on the relevant programs.

Internally, however, other institutions

have been able to use innovative approaches to improve the effectiveness of

their incentive programs. NCSU’s program, one of the oldest and most

influential, stands out for its use of data from its parallel textbook lending

program to inform choices of target for the textbook alternative incentive

program (Thompson et al., 2017). This hybridization shows the value of taking a

multivalent approach to textbook affordability and how one initiative at an

institution can be used to improve another. Kansas State’s program is

remarkable for its unusual level of success and penetration into the culture of

the university, with support from across the administration and multiple units

of the institution, and a funding pipeline directly from university-level

student fees and donations (Lashley et al., 2017). The secret to its success

may be in its origin as a multi-departmental faculty collaboration, which was

effective and timely enough to attract the interest and support of the administration.

Finally, the program at East Carolina University and UNC-Greensboro is unique

in being a partnership between two universities to create a communal incentive

program and thus maximize their resources and return. Even where other

institutions are within the same state or even system, most have tended to

maintain their own individual programs. The case of East Carolina University

and UNC-Greensboro, however, alongside that of the University System of Georgia

shows that cross-institutional collaboration has the potential to make

universities more successful in their efforts than they could be alone.

Table 8

Planned

Strategies for Ensuring Sustainability and Increasing Impact by Institution

|

Institution |

Sustainability

and impact strategies planned |

|

University of Massachusetts-Amherst |

Targeting high-enrolment/high-cost

courses Increasing collaboration across campus Moving to a tiered funding structure Increasing overall funding Providing release time for

participating faculty |

|

North Carolina State University |

Targeting high-enrolment/high-cost

courses Providing greater support to

participants Moving to a tiered funding structure Seeking support from student

government Department- or curriculum-level

replacement |

|

Kansas State University |

Increasing collaboration across campus Department- or curriculum-level

replacement Funding program from student tuition |

|

UCLA |

Targeting high-enrolment/high-cost

courses Seeking more applicants Assessment and program improvement |

|

San Jose State University |

Targeting high-enrolment/high-cost

courses Department- or curriculum-level

replacement Seeking more applicants |

|

University of Oklahoma |

Targeting high-enrolment/high-cost

courses Increasing collaboration across campus Providing greater support to

participants Pushing open sharing of

adapted/created materials |

|

East Carolina University &

University of North Carolina-Greensboro |

Targeting high-enrolment/high-cost

courses Providing greater support to

participants |

|

University of Texas at San Antonio |

Increasing collaboration across

institutions |

|

Rutgers University |

Increasing student awareness of

affordability initiatives |

|

University of Washington |

Using Rebus Foundation partnership to

distribute labor |

|

Florida State University |

Targeting high-enrolment/high-cost

courses Increasing collaboration across campus Increasing collaboration across

institutions |

|

University of North Dakota |

Increasing collaboration across campus Seeking support from student

government |

Discussion

Limitations

By its nature, the present review is

limited in its representation of textbook alternative incentive programs. As a

narrative review of the literature, it is bound by the acknowledged limitations

of such reviews, specifically a lack of critical appraisal of the evidence

found in the literature and strict evaluative criteria for inclusion. Given the

relative newness of these types of programs and the scarcity of the available

literature, all relevant studies were included to maximize the size of the data

pool without regard for methodological rigour by individual authors. This

uncritical approach and the inconsistencies in available data from the studies

that were included may ultimately skew the perceived results.

Furthermore, for the reasons that were

discussed in the Methods section, I consulted only published literature (and

primarily peer-reviewed scholarly and professional literature). This decision

conflicts, however, with the fact that even the oldest programs of this type

are less than a decade old, and many programs are likely not yet at a stage to

yield publishable results. Programs not represented in this review may eventually

yield significantly different results than those that have been discussed. Many

programs are also likely still not in their final forms and may continue to

change over time given the relative newness of these types of intervention.

There is a need for ongoing investigation and review of incentive programs like

those discussed here as well as similar discussion of programs at community

colleges and outside the U.S.

Libraries as Collaborative Leaders

It is fair to say that libraries provide

the leadership for the majority of incentive programs discussed here. Equally

apparent, however, is that in each of these cases partnerships with other

bodies across campus, and even outside of it, have been vital. Involving administrators, faculty, and

students in the process of managing incentive programs and other textbook

affordability measures has been a key component of the success of all of these

programs and has allowed the library to build buy-in across communities, share

leadership with other stakeholders, and learn more about their needs and

perspectives on the issues. Working with broader OER organizations and

communities also provides leadership support for librarians in working with

these programs and in many cases has helped to source the resources that

faculty use when replacing their textbooks (such as in the cases of

partnerships with OpenStax and the Open Textbook Network). The program

descriptions indicate that support from the state government can increase what

an incentive program is capable of offering and accomplishing—but it is quite

possible for a program to be very extensive, well-funded, and successful

without the support of the state, such as in the case of Kansas State. Funds

can be drawn from a variety of sources, and strong collaborations within campus

seem from the literature to be a more reliable predictor of success than

support from without.

Benefits of Incentive Programs

Another strong indication of the

literature is that the return on investment of incentive programs is very high,

both in terms of numbers of students impacted and the textbook cost savings

effected. None of the programs examined seem to have invested much more than

$50,000 total in their incentives and most much less than that. Yet student

cost savings have been reported in the hundreds of thousands or even millions

for the same programs with impacts on hundreds, thousands, or tens of thousands

of students. As previously mentioned, establishing direct connections between

the inputs and outputs of various programs is difficult due to their

differences in measurement approaches, but the total funding amount for a

program does not always seem to be closely related to its eventual impact. The

number of students that each individual faculty recipient is able to reach by replacing

textbooks may be a more significant factor than how many faculty

receive awards or the size of the awards they receive. In any case, it is

impressive to produce these kinds of results by distributing micro-grants of

only $500 to $2500 to only 10 to 30 faculty members. Tiered awards by enrolment

numbers may be an effective approach to targeting higher-impact courses,

although enough assessment data of such structures is not yet available to make

a determination.

Beyond cost savings, faculty and student

responses to these programs have been reported as highly positive across all

studies where they have been collected, with some notable minor drawbacks

failing to outweigh the overall benefits. Not only do students and faculty both

value the financial savings for students in these cases, but faculty at some

institutions have reported feeling that they have become better, more

thoughtful, and more innovative educators as a direct result of implementing

textbook alternatives. Using OER or strategic selections from the library

collection appears to help faculty think more critically and more deeply about

their subject matter than does simply using a preset commercial textbook, and

developing new OER can be seen as a valuable scholarly pursuit that deepens disciplinary

knowledge and pedagogical deliberation. A vitally important next step, however,

will be the appropriate recognition of this work with respect to faculty tenure

and professional advancement decisions. Not only is it vital to acknowledge

faculty efforts toward creating open resources as the scholarly participation

that these resources represent, but also it is necessary for faculty to be

supported in this way if they are to make time for participation in the OER

world amid their already busy schedules. The studies also indicate the vital

importance of providing support in the form of training, professional

development, and guidance as faculty take on these new challenges so that their

efforts are successful and their participation in the program continues.

Encouragingly, there is mounting evidence that fears about textbook

replacement’s negative impacts on student performance have been unfounded, as

the majority of cases have seen unchanged or improved academic achievement with

the implementation of new resources. The positive impact is likely even greater

than has been reported. The points made by Grimaldi et al. (2019) about the

insufficiency of statistical approaches in this area are well taken.

Conclusions

The emerging literature on textbook alternative

incentive programs indicates that these programs have a significant positive

impact. Primarily, the studies considered here have found these programs to

greatly benefit students financially and to inspire improvements to faculty

pedagogy. Furthermore, the programs are relatively affordable to begin and

maintain, especially compared to the returns on the investment that have been

reported. There are still significant barriers to entry associated with these

initiatives, particularly faculty time and training and buy-in from both

faculty and students, but cross-campus collaborations and expanding the types

of incentives offered to faculty may help to increase participation. It is also

worth noting, however, that there is a great deal of diversity in institutional

approaches to these types of programs. The literature shows no standardization

to speak of nor even sufficient evidence for a set of best practices or

recommendations to emerge. While enough prior examples exist that each new

institution initiating an incentive program need not reinvent the wheel,

program developers at each institution will have to carefully consider their

institution's individual needs and characteristics to develop the approach to

funding, leadership, number of awardees, implementation, and assessment

practices that will be most effective locally.

A major concern for the future of

several programs considered here is increasing student impact and the resulting

cost savings. This is not surprising given that these are the primary criteria

by which these types of programs have tended to be assessed. A number of

potential strategies for accomplishing this have been discussed, but it may be

that the most effective way to increase impact is simply to find ways to

develop buy-in and investment from more and more units across campus as

evidenced by the extraordinary success of the program at Kansas State. Indeed,

the most important factor in these programs so far may also be the one that

holds the key to growth and success in their future: partnerships.

Collaborations within and between universities between different fronts in the

fight for college affordability and across systems and consortia all seem to

hold the most promise in terms of improving and expanding textbook alternative

incentive programs and other efforts to improve educational access and success.

The strength of communities and organizations working together is clearly felt

in all the success stories that have been recounted here, and if that lesson is

taken to heart, even greater successes may lie ahead.

As research in this area is still

limited, a number of possible directions exist for future studies to pursue. A

review of the literature (and possibly other documentation) on programs at

community colleges would be of value for comparison to these findings and

analysis of the similarities and differences in approach between different

institutional types. Studies of the practices of institutions outside the U.S.

would also be of significant interest. A more comprehensive review of data on

all existing incentive programs, including those without associated

publications, would be a daunting task but also potentially of substantial

value. Furthermore, as indicated by Grimaldi et al. (2019), there is a need for

more rigorous and more nuanced analysis of the impact of implementing

alternatives on students' academic performance because the results in this area

have thus far been inconclusive. Similarly, moving toward standardization of

institutional formulae for calculating student cost savings would be

tremendously beneficial as future researchers seek to more accurately

understand the impacts of these programs.

References

Agee, A., & Mune, C. (2014). Getting faculty into the fight: The battle

against high textbook costs. Against the Grain, 26(5),

Article 9. https://doi.org/10.7771/2380-176X.6843

Bailey, C.,

& Poo, A. (2018). TEAMing up with faculty: A new

tactic in the textbook battle. Against

the Grain, 30(5), Article 53. https://doi.org/10.7771/2380-176X.8160

Batchelor, C.

Transforming publishing with a little help from our friends: Supporting an open

textbook pilot project with Friends of the Libraries grant funding. In A. Wesolek, J. Lashley, & A. Langley (Eds.), OER: A

field guide for academic librarians (pp. 415–432). https://scholarworks.umass.edu/librarian_pubs/71

Belikov, O.

M., & Bodily, R. (2016). Incentives and barriers to OER adoption: A

qualitative analysis of faculty perceptions. Open Praxis, 8(3), 235–246.

http://dx.doi.org/10.5944/openpraxis.8.3.308

Bell, S. J.

(2012). Coming in the back door: Leveraging open textbooks to promote scholarly

communications on campus. Journal of Librarianship and Scholarly

Communication, 1(1), eP1040. https://doi.org/10.7710/2162-3309.1040

Croteau, E.

(2017). Measures of student success with textbook transformations: The

Affordable Learning Georgia Initiative. Open Praxis, 9(1),

93–108. https://doi.org/10.5944/openpraxis.9.1.505

Delimont, N.,

Turtle, E., Bennett, A., Adhikari, K., & Lindshield,

B. (2016). University students and faculty have positive perceptions of

open/alternative resources and their utilization in a textbook replacement

initiative. Research in Learning Technology, 24(1),

1–13. https://doi.org/10.3402/rlt.v24.29920

Farb, S.,

Glushko, R., Orfano, S.,

& Smith, K. (2017). Reducing the costs of course materials. Serials

Review, 43(2), 158–162. https://doi.org/10.1080/00987913.2017.1316628

Farb, S.,

& Grappone, T. (2014). The UCLA Libraries

Affordable Course Materials Initiative: Expanding access, use, and

affordability of course materials. Against the Grain, 26(5),

Article 14. https://doi.org/10.7771/2380-176X.6848

Gallant, J.

(2015). Librarians transforming textbooks: The past, present, and future of the

Affordable Learning Georgia Initiative. Georgia

Library Quarterly, 52(2), 12–17. https://digitalcommons.kennesaw.edu/glq/vol52/iss2/8

Grimaldi, P.,

Waters, A., & Baraniuk, R. (2019). Do open

educational resources improve student learning? Implications of the access

hypothesis. PLoS One, 14(3),

1–14. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0212508

Ivie, D.,

& Ellis, C. Advancing access for first-generation college students: OER

advocacy at UT San Antonio. In A. Wesolek, J.

Lashley, & A. Langley (Eds.), OER: A field guide for academic librarians

(213–238). https://scholarworks.umass.edu/librarian_pubs/71

Lashley, J.,

Cummings-Sauls, R., Bennett, A., & Lindshield, B. (2017). Cultivating textbook alternatives

from the ground up: One public university’s sustainable model for open and

alternative educational resource proliferation. International Review of

Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 18(4), 212–230. https://doi.org/10.19173/irrodl.v18i4.3010

Levitan, M.

(2018, August 6). Textbook costs drop as nearly half of colleges use OpenStax. Diverse Issues in Higher Education. https://diverseeducation.com/article/121872/

National Center

for Education Statistics. (2017). Average

total cost of attendance for first-time, full-time undergraduate students in

degree-granting postsecondary institutions, by control and level of

institution, living arrangement, and component of student costs: Selected

years, 2010-11 through 2016-17 [Data set]. Retrieved from https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d17/tables/dt17_330.40.asp?current=yes

Senack, E.

(2014). Fixing the broken textbook

market. U.S. PIRG Education Fund and The Student PIRGs. https://uspirg.org/reports/usp/fixing-broken-textbook-market

Smith, J.

(2018). Seeking alternatives to high-cost textbooks: Six years of the Open

Education Initiative at the University of Massachusetts Amherst. In A. Wesolek, J. Lashley, & A. Langley (Eds.), OER: A

field guide for academic librarians (333–350). https://scholarworks.umass.edu/librarian_pubs/71

Soper, D.,

Wharton, L., & Phillips, J. (2018). Expediting OER on campus: A

multifaceted approach. In K. Jensen & S. Nackerud

(Eds.), The evolution of affordable content efforts in the higher education

environment: Programs, case studies, and examples (135–149). https://open.lib.umn.edu/affordablecontent/chapter/expediting-oer-on-campus-a-multifaceted-approach/

Subramony, D.

(2018). Instructors’ perceptions and experiences re: creating and implementing

customized e-texts in education courses. Educational Considerations, 44(1),

13. https://doi.org/10.4148/0146-9282.1692

Thomas, W.J.,

& Bernhardt, B.R. (2018). Helping keep the costs of textbooks for students

down: Two approaches. Technical Services

Quarterly, 35(3), 257–268. https://doi.org/10.1080/07317131.2018.1456844

Thompson, S.,

Cross, W., Rigling, L., & Vickery, J. (2017).

Data-informed open education advocacy: A new approach to saving students money

and backaches. Journal of Access Services, 14(3),

118–125. https://doi.org/10.1080/15367967.2017.1333911

Todorinova, L.,

& Wilkinson, Z. (2019). Closing the loop: Students, academic libraries, and

textbook affordability. The Journal of Academic Librarianship, 45(3),

268–277. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2019.03.010

Walker, S.

(2018). Facilitating culture change to boost adoption and creation of open

educational resources at the University of North Dakota. In K. Jensen & S. Nackerud (Eds.), The Evolution of affordable content

efforts in the higher education environment: Programs, case studies, and

examples (150–161). https://open.lib.umn.edu/affordablecontent/chapter/facilitating-culture-change-to-boost-adoption-and-creation-of-open-educational-resources-at-the-university-of-north-dakota/

Waller, J.,

Taylor, C., & Zemke, S. (2018). From start-up to adolescence: University of

Oklahoma's OER efforts. In A. Wesolek, J. Lashley,

& A. Langley (Eds.), OER: A field guide for academic librarians

(351–380). https://scholarworks.umass.edu/librarian_pubs/71

Wiley, D.,

Bliss, T., & McEwen, M. (2014). Open educational resources: A review of the

literature. In J. M. Spector, M. D. Merrill, J. Elen,

& M.J. Bishop (eds.), Handbook of research on educational communications

and technology (4th ed., pp. 781–789).