Research Article

Factors Associated with the Prevalence of Precarious

Positions in Canadian Libraries: Statistical Analysis of a National Job Board

Ean Henninger

Liaison

Librarian

Simon

Fraser University Library

Burnaby,

British Columbia, Canada

Email:

ean_henninger@sfu.ca

Adena Brons

Digital

Scholarship Librarian & Liaison Librarian

Simon

Fraser University Library

Burnaby,

British Columbia, Canada

Email:

adena_brons@sfu.ca

Chloe

Riley

Library

Communications Officer

Simon

Fraser University Library

Burnaby,

British Columbia, Canada

Email:

chloe_riley@sfu.ca

Crystal

Yin

Liaison

Librarian

Simon

Fraser University Library

Burnaby,

British Columbia, Canada

Email:

yya192@sfu.ca

Received: 2 June 2020 Accepted: 27 July 2020

![]() 2020 Henninger, Brons, Riley,

and Yin.

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative

Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

2020 Henninger, Brons, Riley,

and Yin.

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative

Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

DOI: 10.18438/eblip29783

Abstract

Objective - To collect and

share information about the prevalence of precarious work in libraries and the

factors associated with it.

Methods - The authors

collected and coded job postings from a nationwide job board in Canada for two

years. Descriptive and inferential statistics were used to explore the extent

of precarity and its relationship with job characteristics such as job type,

institution type, education level, and minimum required experience.

Results - The authors

collected 1,968 postings, of which 842 (42.8%) were coded as precarious in some

way. The most common types of precarious work were contracts (29.1% of all

postings) and part-time work (22.7% of all postings). Contracts were most

prevalent in and significantly associated with academic libraries and librarian

positions, and they were most often one year in length. Both on-call and

part-time work were most prevalent in school libraries and for library

technicians and assistants, and they were significantly associated with all

institution types either positively or negatively. Meanwhile, precarious

positions overall were least prevalent in government and managerial positions.

In terms of education, jobs requiring a secondary diploma or library technician

diploma were most likely to be precarious, while positions requiring an MLIS

were least likely. The mean minimum required experience was lower for all types

of precarious positions than for stable positions, and the prevalence of

precarity generally decreased as minimum required experience increased.

Conclusion - The proportion

of precarious positions advertised in Canada is substantial and seems to be

growing over time. Based on these postings, employees with less experience,

without advanced degrees, or in library technician and assistant roles are more

likely to be precarious, while those with managerial positions, advanced

degrees, or more experience, are less likely to be precarious. Variations in

precarity based on factors such as job type, institution type, education level,

and minimum required experience suggest that employees will experience

precarity differently both within and across library systems.

Introduction

Precarious labour is an

employment structure defined by the International Labour

Organization as involving:

uncertainty as to the duration of employment, multiple

possible employers or a disguised or ambiguous employment relationship, a lack

of access to social protection and benefits usually associated with employment,

low pay, and substantial legal and practical obstacles to joining a trade union

and bargaining collectively. (2012, p. 27)

Precarious labour takes many

forms, all with the potential to produce material and psychological insecurity

and vulnerability among workers. Current examples of precarious labour include jobs associated with the gig economy, the

trend towards adjunctification in higher education,

and the use of temporary and poorly paid workers in farms and processing

plants.

Precarious labour also exists

in all kinds of libraries and it affects workers at all levels. It can include

workers in part-time or full-time positions, temporary or permanent positions,

and on-call or auxiliary positions. Although authors in recent years have begun

to address the effects of precarious library work (Henninger, Brons, Riley, & Yin, 2019; Lacey, 2019; Skyrme & Levesque, 2019), there is still very little

scholarship documenting the prevalence of precarious work or describing the

characteristics of precarious jobs. Accordingly, this article focuses on

examining the prevalence of precarious library jobs and the factors associated

with them. It begins by situating itself relative to the literature on library

job posting analyses and precarious employment. It continues by describing the

methodology and the results of a study that involved collecting job postings

from a nationwide job board over two years, coding the postings into various

categories, and conducting descriptive and inferential statistical analyses.

Finally, it discusses the results and their implications for job searching,

hiring, employment, and more.

One way of describing the differences between precarious

and stable jobs is to establish the prevalence of precarious work, as well as

associations within that prevalence, such as education required, years of

experience, or job position. Knowing how common precarity is and how it

expresses itself within the profession will aid interested parties in imagining

and enacting alternatives where desirable.

Literature Review

Although literature on the prevalence and characteristics

of precarity in libraries is limited, the research that does explore this topic

centers on surveys and analyses of job postings. Surveys are a common method of

exploring the prevalence of certain characteristics in library jobs; however,

there have been few surveys conducted and published specifically with precarity

in mind. In Canadian academic settings, there have been surveys describing the

prevalence of precarious work and its negative effects on individuals as well

as academic institutions (Pasma & Shaker, 2018;

Foster & Birdsell Bauer, 2019), but these surveys

determine librarians in precarious contracts to be out of scope, despite the

fact that many librarians are faculty members at such institutions. Bladek (2019) pointed out that this omission is

unfortunately common, with few reports or studies on precarity within academia

including precariously employed librarians, and with LIS (Library and

Information Studies) statistics rarely differentiating between full-time or

part-time and temporary or permanent positions (p. 486). In the public context,

a recent Canadian Union of Public Employees survey of over 800 public library

employees in Canada classified 28% of respondents as precarious and a further

24% as vulnerable to precarity, with 49% in stable or secure positions (CUPE,

2017, p. 26).

In the United States, Wilkinson (2015) surveyed 73

current and former part-time librarians who graduated from MLIS (Masters in

Library and Information Studies) programs between 2008-2012 and had held at

least one part-time position following graduation (p. 348). For these part-time

positions, the majority of respondents worked in academic and public libraries

and over 55% worked concurrently in more than 1 position (Wilkinson, 2015, p.

348 & p. 352).

Another common means of exploring trends in library

employment and characteristics of library-related jobs is through the analysis

of job advertisements. Studies have explored trends in advertisements for

librarian positions in areas such as government documents (Sproles &

Clemons, 2019), digital initiatives (Skene, 2018), and electronic resources

(Ferguson, 2018). Others have explored the relationship between posted

qualifications and professional competencies or standards (Gold & Grotti, 2013; Hartnett, 2014; Henricks & Henricks-Lepp, 2014; Maciel, Kaspar, & vanDuinkerken,

2018). Additional studies have focused on assessing the professional skills

required in postings for LIS program curriculum development (Messum, Wilkes, Peters, & Jackson, 2016; Wise,

Henninger, & Kennan, 2011). However, such studies focus almost exclusively

on positions requiring an MLIS degree, and very few explore or note aspects

related to precarity in their analyses.

One exception is a study by Wilkinson (2016), which

analyzes 56 part-time librarian positions in Pennsylvania and New Jersey.

Wilkinson (2016) found that the postings were primarily from academic libraries

(48%) and public libraries (43%), with minimal postings from special libraries

(7%) and school libraries (2%) (p. 74). In addition, she found that only 64% of

the part-time postings included hours of work; of those that did indicate

hours, the most common range was 16-20 hours (25%) (Wilkinson, 2016, p. 75).

Another exception is Maccaferri

and Harhai’s (2019) study of public library job

advertisements, which incorporated an analysis of both part-time postings and

postings that did not require an MLIS. Their study covered 1 year’s worth of advertisements on a Pennsylvania library

email list and analyzed 124 public library postings. Postings were fairly

evenly divided between “professional” (MLIS-holding) positions (52.42%) and

“non-professional” positions (47.58%) (Maccaferri

& Harhai, 2019, p. 12). The study found that

94.35% of all jobs posted were permanent positions (Maccaferri

& Harhai, 2019, p. 12). However, “professional

positions were predominantly full-time (80%) while non-professional positions

were predominantly part-time (86.44%)”, representing a stark disparity based on

educational level (Maccaferri & Harhai, 2019, p. 13). Unfortunately, the authors did not

break down the number of work hours within these part-time positions, nor did

they identify on-call or auxiliary postings in the analysis.

Reviewing the literature reveals a significant lack of

information about the prevalence and characteristics of precarious library

jobs. Despite some studies touching on the issue, the extent of precarity

remains under-examined, with most surveys and job advertisement analyses having

minimal inclusion of precarious positions. As well, few studies use inferential

analyses, which could enable authors to make generalizations

or predictions about the broader population of actual jobs from job postings.

According to Harper’s (2012) review of 70 job advertisement analyses in LIS,

this minimal use of inferential statistics is one criticism of the genre.

The scholarship that does exist primarily focuses on

part-time jobs and does not include contract or on-call jobs. In some cases,

this limitation may be due to data collection methods, as job aggregators or

national email lists may not include part-time or limited-term positions. For

example, in a study of entry-level librarian positions, Tewell

(2012) captured 1385 postings over a year, of which only 78 (5.6%) were

part-time (20 or fewer hours) or temporary (less than 1 year) (p. 414).

Wilkinson (2016) concurs that job advertisement analyses often exclude

part-time positions, resulting “in a severe lack of reliable information about

the duties, hours, and salaries of part-time professionals and

paraprofessionals in libraries.” (p. 68). This exclusion may result in an

overrepresentation of permanent full-time positions in analyses of job

advertisements.

This article seeks to address some of these gaps through

both descriptive and inferential analyses of a dataset representing two years’

worth of job postings from a Canada-wide online job board.

Aims

The aim of this research study is to better understand

the prevalence of precarious library work and the factors associated with it,

providing insight into the landscape of library employment trends. The research

questions for this project are:

·

What is the

prevalence of precarious library job postings in Canada?

o

Does the prevalence

vary based on key characteristics of those postings?

·

To what extent are

different characteristics of library job postings associated with precarity?

o

Do the

characteristics of job postings change based on whether or not a job is

precarious or based on the specific type of precarity (i.e., contract, on-call,

or part-time)?

Methods

The methodology for this study was initially informed by

the authors’ status as precarious contract workers themselves. They determined

that analyzing advertisements from a single website would be a means of

collecting information that was within the scope of their shared capacity. The

website chosen for analysis was the Partnership Job

Board, which is maintained by the

British Columbia Library Association to support members of The Partnership,

Canada’s national network of provincial and territorial library associations.

The authors used a predetermined weekly schedule to

review jobs posted on this site over the course of their assigned weeks,

entering posting data into a shared spreadsheet, and saving copies of the

postings to a shared drive. The authors assigned each posting a job ID

(identification) number and then entered additional identifying data consisting

of date posted, date closed, job title, institution name, city, and province or

territory. They also collected and coded data for aspects of job postings,

listed with coding criteria in the Appendix, that were decided a priori to be

of potential interest in determining the prevalence of precarity and factors

associated with it. Finally, note fields were used to provide any necessary

context for how the postings were coded. A total of 1,968 postings were

collected over a period of 2 years, from November 15, 2017 to November 14,

2019.

After collecting postings, the authors reviewed the

spreadsheet for consistency and recoded postings in two categories. Institution

types were recoded to split government positions into their own category, and a

previously existing “special” category was collapsed into “other.”

Additionally, the majority of the postings coded as “other” under the education

level were recoded into other categories. The resulting data set was cleaned to

support legibility and data filtering.

The data analysis methods employed consisted of

descriptive statistics using Tableau, showing the frequencies and proportions

of precarious jobs relative to non-precarious jobs, and inferential statistics

using SPSS 25. The data used for inferential analysis consisted of two kinds of

variables. There were seven nominal-level variables: three categories with

multiple entries defining institution type, job level, or education level

respectively, and four dichotomous categories defining whether or not a job was

precarious, contract, on-call, or part-time, respectively. There were also two

continuous, ratio-level variables, both expressed in months: contract duration

and minimum required experience. Due to a tendency in job postings to round

both contract length and minimum required experience to the nearest year, these

two variables were not normally distributed. Given this, the broader population

of actual jobs would likely replicate these non-normal distributions.

The authors performed Pearson chi-square tests for

independence to determine if significant differences existed among institution

type, job level, and education level, and each of the four dichotomous

variables describing whether or not a job was precarious, contract, on-call, or

part-time. These tests were appropriate to compare two nominal-level variables

consisting of categorical and independent groups.

The authors additionally performed independent-sample

Welch’s t-tests to look for significant associations between the continuous

variable of minimum months of experience required and each of the four

dichotomous variables describing whether or not a job was precarious, contract,

on-call, or part-time. These tests were appropriate to compare differences in

means between two independent samples where equal variance could not be

assumed, and they remain robust for large and unequal sample sizes even when

variables are not normally distributed. The authors also calculated confidence

intervals for these tests.

In one instance, the authors calculated Spearman’s rho to

correlate the two ratio-level variables of contract length and minimum required

experience. This non-parametric statistic using ranked data was appropriate

given the non-normal distribution of these continuous variables.

For these analyses, the authors set the alpha level for

statistical significance at α = 0.011

based on the equation in Lakens (2018): α = 0.05/√(1968/100).

Although α is conventionally set to 0.05 in many settings, sample sizes in this

study were easily large enough to make weak effects statistically significant

for sufficiently high values of α, increasing the chances of observing an

effect where none existed.

Effect size is important to report along with statistical

significance because it shows the magnitude of a change that one variable

produces on another variable, allowing for more interpretation of that effect’s

importance. Accordingly, the authors calculated two measures of effect size:

Cramer’s V for chi-square tests, denoted as ϕc, and Hedge’s g for t-tests, which was preferred to

Cohen’s d as it weights effect size

based on sample sizes. Differences between means and the sizes of test values

(χ2 and t) relative to other values for the same kinds of tests also give

indications of effect size. For chi-square tests, the authors also calculated

standardized residuals, which measure the strength of the difference between

observed and expected values and show how much each category in a chi-square

test contributes to the overall association. At α = 0.011, a standardized residual contributes significantly if it

lies outside of ± 2.54. As Cohen (1988) discusses, the exact meaning of effect

size depends in part on the context, content, and method of a given study. In

the absence of any prior conventions for this kind of study, the authors used

the conventions recommended by Cohen for Cramer’s V listed in Table 1, and

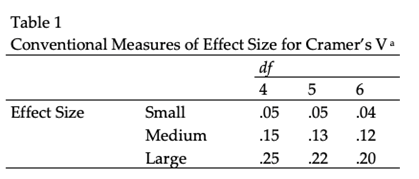

Hedge’s g, where small = 0.2, medium = 0.5, and large = 0.8.

a Note. df = degrees of

freedom for contingency tables created for chi-square tests. Adapted from a

table and conventions by Cohen (1988).

Results

Overall Prevalence

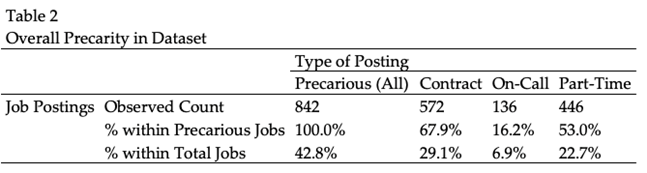

Over 2 years, the authors collected 1,968 job postings

from the Partnership Job Board and coded them according to the

methodology. Table 2 shows the overall prevalence of precarity and its

subtypes. These subtypes were not mutually exclusive, as all on-call jobs were

part-time, many contract jobs were also part-time, and some contract jobs were

on-call.

Figure 1 shows that the number of jobs posted by province

was uneven, with 955 jobs based in Ontario and 565 in British Columbia,

together comprising 77.2% of all jobs posted. Postings from New Brunswick had

the highest prevalence of precarious employment (67.4%), followed by Quebec

(48.6%), British Columbia (45.7%), and Ontario (44.4%).

As seen in Figure 2, the prevalence of precarity

increased from the first year of data collection to the second. In Year 1

(November 15, 2017 to November 14, 2018), precarious jobs made up 39.9% of all

jobs posted. In Year 2 (November 15, 2018 to November 14, 2019), precarious

jobs made up 45.9% of all jobs posted. Overall job postings were roughly equal

in each year, with 998 jobs posted in Year 1 and 970 jobs posted in Year 2.

Figure 1

Job postings by precarity

and province.

Figure 2

Job postings by precarity

and year posted.

Institution Type

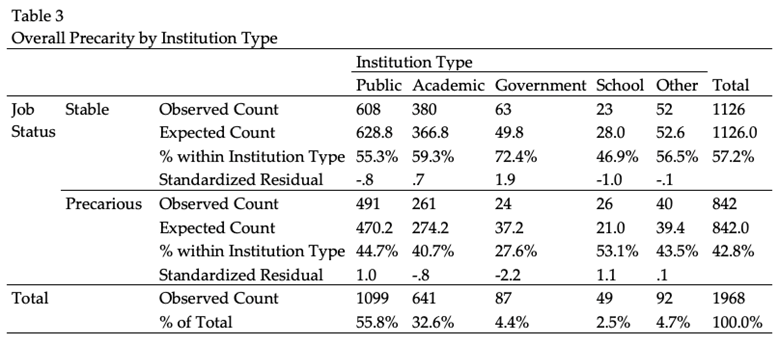

Of all jobs posted in this period, the majority were from

public libraries (55.8%), followed by academic libraries (32.6%). When stable

and precarious postings were analyzed by type of institution, as seen in Table

3, precarity was least prevalent among government library jobs (27.6%) and most

prevalent among school library jobs (53.1%). The chi-square test showed a

significant association between type of institution and whether or not a job

was precarious χ2 (4, N = 1968) = 13.07, p = .011, and the effect size was small, ϕc = .08. No single

category of institution significantly contributed to this association, meaning

that no category had more or fewer precarious positions than expected.

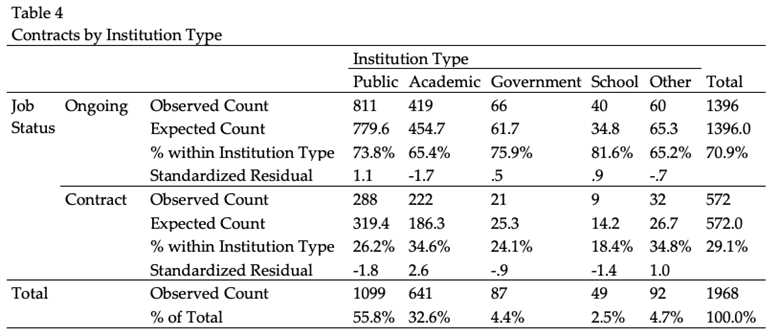

Limited term contracts were the most prevalent in

academic libraries (34.6%), followed by public libraries (26.2%), as seen in

Table 4. They were least prevalent in school libraries (18.4%). There was a

significant association between type of institution and whether or not a job

was a contract χ2 (4, N = 1968) = 19.20, p = .001, also indicating a small effect size, ϕc = .10. Academic

libraries were the only significant driver of this association, with more

contract postings than expected.

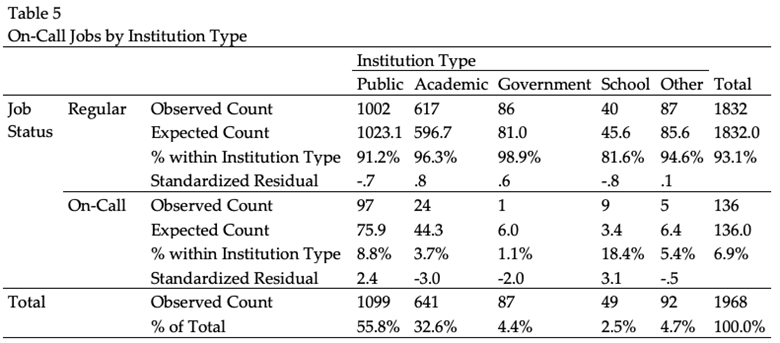

Table 5 shows that on-call postings were most prevalent

for school libraries (18.4%) and least prevalent in government jobs (1.1%).

There was a significant association between institution type and whether or not

a job was on-call χ2 (4, N = 1968) = 31.06, p < .001, again demonstrating a small effect size, ϕc =

.13. School libraries contributed significantly to this association, with more

on-call postings than expected, as did academic libraries with fewer than

expected.

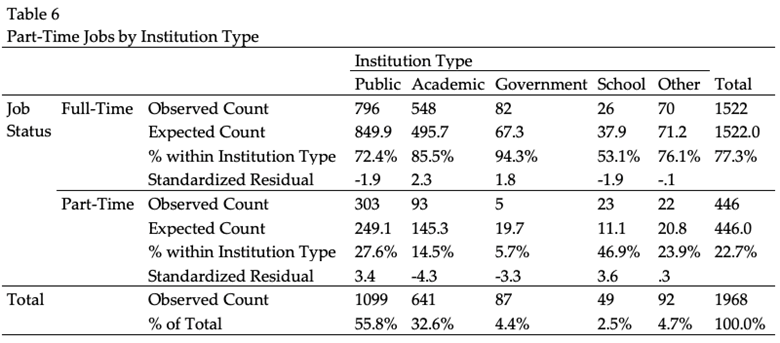

Finally, part-time postings were most prevalent in school

library settings (46.9%) and least prevalent in government institutions (5.7%),

as seen in Table 6. There was a significant association between type of

institution and whether or not a job was part-time χ2 (4, N =

1968) = 70.18, p < .001,

indicating a medium effect size, ϕc = .19. All institution types significantly

contributed to this association, with public and school library positions

having more part-time positions than expected, and academic and government

positions having fewer.

Job Type

Postings for librarian jobs were the most prevalent type

of position represented in the 2-year period (37.4%), followed by managers

(23.4%), and technicians (18.4%). Meanwhile, archivist postings were the least

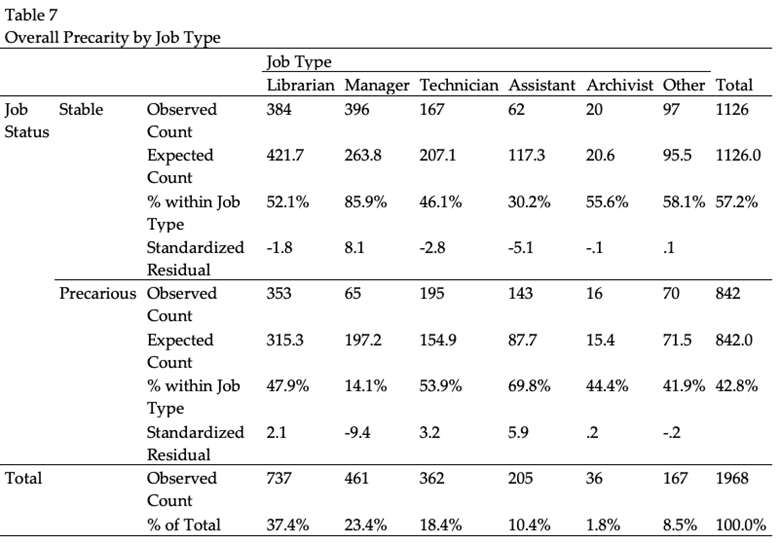

prevalent (1.8%). When analyzing the type of position for precarity, as seen in

Table 7, precarity was most prevalent among assistant positions (69.8%) and

least prevalent among manager positions (14.1%). Precarious manager positions

were sometimes due to term limits for head or chief librarians, but the authors

still coded these as precarious since they met the technical definition of a

limited-term contract. There was a significant association between job type and

whether or not a job was precarious χ2

(5, N = 1968) = 242.00, p < .001, representing a very large

effect size, ϕc

= .35. Manager positions were a highly significant contributor to this

association with far fewer precarious positions than expected, while assistant

and technician positions also contributed with more than expected.

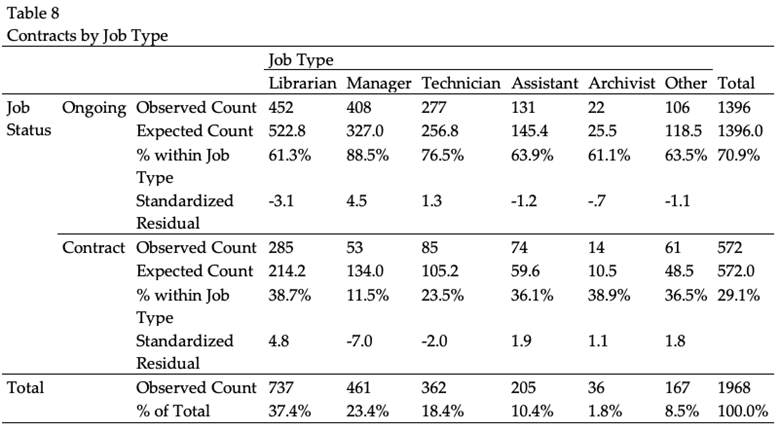

Limited term contracts were most prevalent among

archivist and librarian positions (38.9% and 38.7% respectively), as seen in

Table 8. There was a significant association between job type and whether or

not a job was a contract χ2

(5, N = 1968) = 118.58, p < .001, and the effect size was

large, ϕc

= .25. Manager and librarian positions were significant drivers of this

association, with the former being more likely than expected to be contracts,

and the latter being more likely than expected to be contracts.

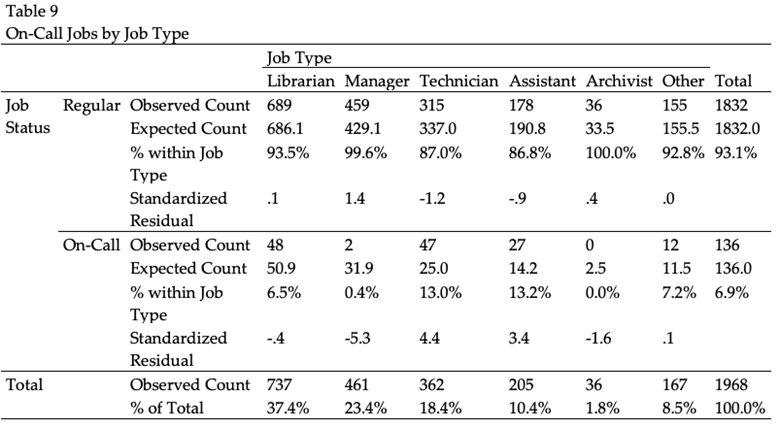

Meanwhile, Table 9 demonstrates that on-call job postings

were most prevalent among assistants (13.2%), and technicians (13.0%). They

were least common for archivists (0.0%), and managers (0.4%), while librarians

were close to the average at 6.5%. There was a significant association between

job type and whether or not a job was on-call χ2 (5, N =

1968) = 66.18, p < .001,

indicating a medium effect size, ϕc = .18. This association was significantly

driven by manager jobs, which were much less likely to be on-call than

expected, and by technician and assistant jobs, which were more likely to be

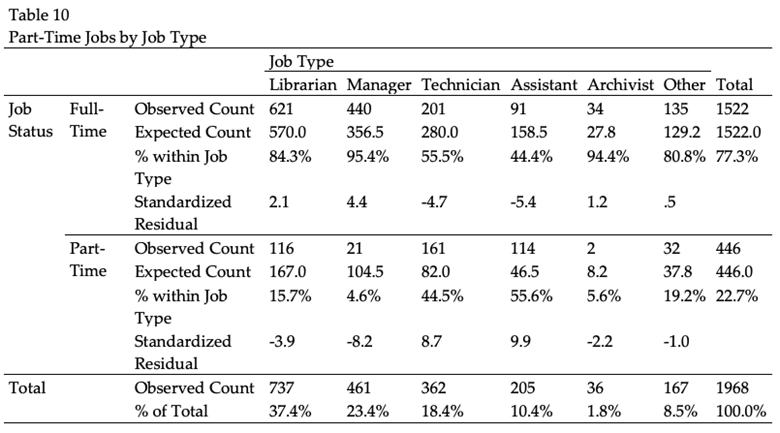

on-call than expected. Part-time job postings, as seen in Table 10, were very

prevalent among assistants (55.6%) and technicians (44.5%). They were least

prevalent among managers (4.6%) and archivists (5.6%). There was a significant

association between job type and whether or not a job was part-time χ2 (5, N = 1968) = 338.81, p

< .001, indicating a very large effect size, ϕc = .42. This

association was significantly driven by jobs of every type except for

archivists, with manager and librarian jobs being less likely than expected to

be part-time, and technician and assistant jobs more likely.

Education level

The authors excluded 75 postings from the analysis of

education levels; 73 jobs that did not specify any educational qualifications

and 2 postings that specified a minimum of Grade 10 education. Of the postings

with required educational qualifications (n = 1893), jobs requiring a MLIS or

equivalent were the most common (58.6%) and jobs requiring a library technician

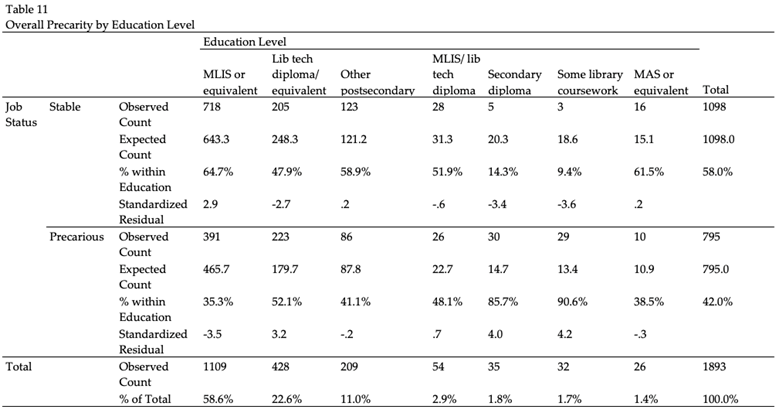

diploma were the next most common (22.6%). When looking at precarity and

education level as seen in Table 11, precarious postings were most prevalent

among jobs requiring some library coursework (90.6%) and jobs requiring a

secondary diploma (85.7%). Rates were substantially lower for all other

categories, with the lowest rate among jobs requiring a MLIS (35.3%). There was

a significant association between educational level and whether or not a job

was precarious χ2 (6, N = 1893) = 98.18, p < .001, and the effect size was large, ϕc = .23. Jobs

requiring some library coursework, secondary diplomas, library technician

diplomas, or MLIS degrees were all significant drivers of this association.

Jobs with MLIS degrees were less likely to be precarious than expected, while

the rest were more likely than expected.

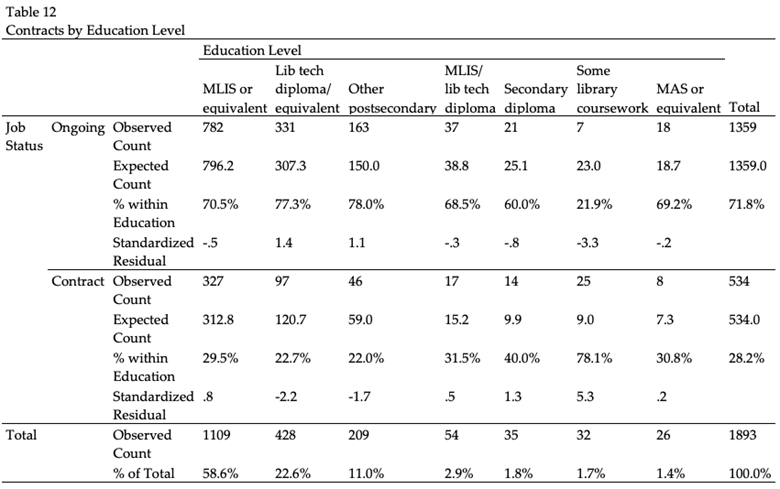

Limited term contracts were by far most prevalent among

positions requiring some library coursework, comprising 78.1% of those

positions as seen in Table 12, and likely reflecting that many of these

postings were meant to be completed during a library degree. They were least

prevalent among jobs requiring other postsecondary degrees (22.0%) and library

technician diplomas (22.7%). There was a significant association between

educational level and whether or not a job was a contract χ2 (6, N =

1893) = 53.50, p < .001,

representing a medium effect size, ϕc = .17. Jobs requiring some library coursework

were the only significant contributors to this association, being more likely

than expected to be contracts.

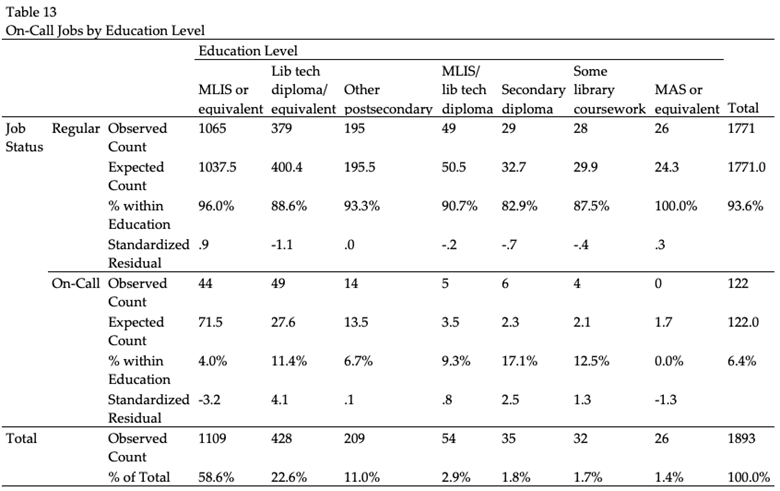

Table 13 demonstrates that the on-call employment

structure was most prevalent among postings requiring secondary diplomas

(17.1%), some library coursework (12.5%), and library technician diplomas

(11.4%). Meanwhile, no on-call jobs required a MAS (Master of Archival Studies)

(0.0%). There was a significant association between educational level and

whether or not a job was on-call χ2

(6, N = 1893) = 40.17, p < .001, and the effect size was

medium, ϕc

= .15. However, 4 cells in this test (28.6%) had an expected count of less than

5, resulting in a substantial loss of statistical power. Jobs requiring library

technician diplomas or MLIS degrees were the only significant drivers of this

association, with the former being more likely and the latter being less likely

than expected to be on-call.

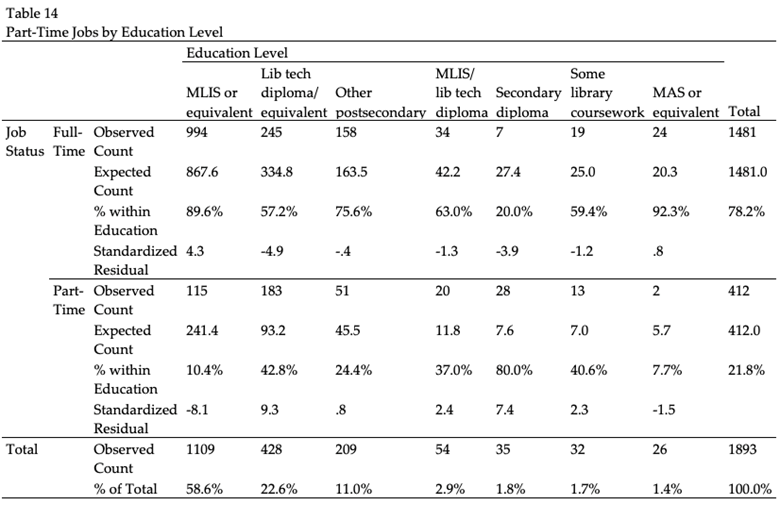

Part-time jobs were extremely prevalent among postings

that required a secondary diploma (80.0%), as seen in Table 14. Part-time

postings were least prevalent when requiring a MAS or MLIS degree (7.7% and

10.4% respectively). There was also a significant association between

educational level and whether or not a job was part-time χ2 (6, n =

1893) = 283.01, p < .001,

indicating a very large effect size, ϕc = .39. Postings requiring library technician

diplomas and secondary diplomas significantly contributed to this association

by being more likely than expected to be part-time, as did postings requiring

an MLIS, which were less likely than expected to be part-time.

Figure

3

Job

postings by precarity and minimum required experience.

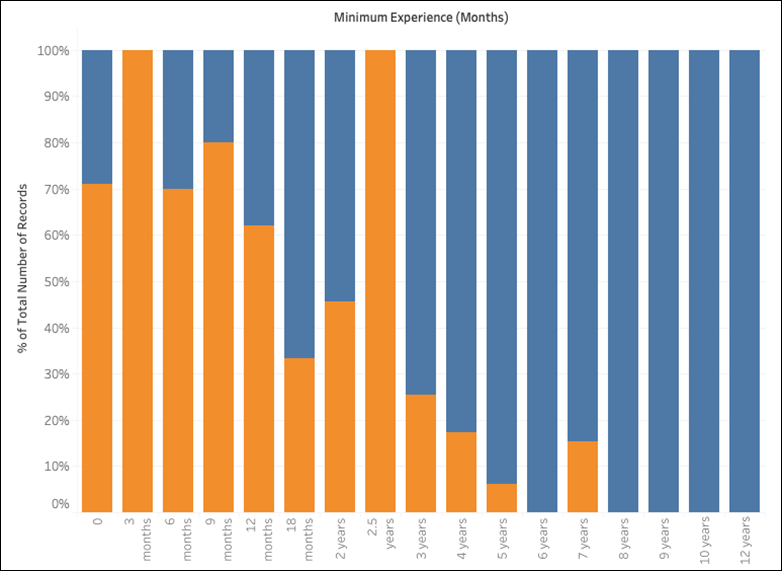

Minimum required experience

Almost half of postings (n = 890, 45.2%) did not specify the minimum experience required for

the position and were excluded from this analysis. Of the remaining postings (n = 1078, 54.8%), the prevalence of

precarity generally decreased as experience increased, as seen in Figure 3. Of

the postings that required less than 1 year of experience (n = 88), 71.63% were precarious. Of the postings requiring 1 year

of experience (n = 162), 62.3% were

precarious. For positions requiring more than 1 year of experience (n = 828), only 27.5% were precarious.

For the postings that listed a minimum required amount of

experience, t-tests showed that on average the non-precarious jobs (M = 41.07, SE = 0.91) required more

months of experience than precarious jobs did (M = 21.48, SE = 0.72).

This difference of -19.59 months, 98.9% CI [-22.54, -16.63], was significant t(1073.58) =

-16.88, p < .001, demonstrating a

large effect size, g = 0.94. Ongoing

jobs (M = 36.92, SE = 0.82) required more months of experience on average than

contract jobs (M = 23.75, SE = 1.02). The difference of -13.17

months, 98.9% CI [-16.52, -9.82], was also significant t(580.75) = -10.03, p < .001, and represented a medium

effect size, g = 0.59. On average,

jobs with stable hours (M = 34.95, SE = 0.72) required more months of

experience than on-call jobs (M =

15.71, SE = 1.55). This difference of

-19.24 months, 98.9% CI [-23.68, -14.80], was significant t(79.50) = -11.28, p < .001, showing a large effect

size, g = 0.86. Finally, full-time

jobs (M = 37.85, SE = 0.80) required more months of experience on average than

part-time jobs (M = 18.54, SE = 0.70). The difference of -19.31

months, 98.9% CI [-22.03, -16.60] was significant t(806.37) = -18.14, p < .001, and had a large effect

size, g = 0.90.

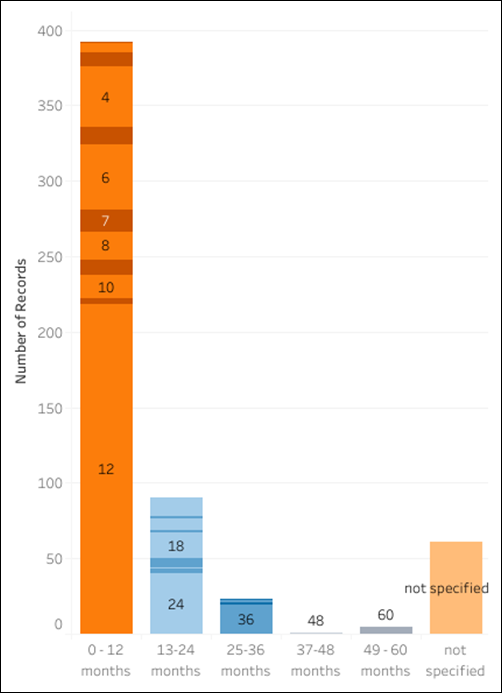

Figure

4

Contract

positions by contract duration.

Contract Length

Temporary positions comprised 29.1% (n = 572) of the

total postings. The authors coded these postings according to contract length

as described in the Appendix and as seen in Figure 4. One-year contracts were

by far the most common, comprising 38.1% of all temporary positions. An

additional 30.4% of contracts were for less than 1 year. For job postings that

reported both contract length and the minimum months of experience required (n = 214), Spearman’s rho found a

significant correlation between the 2 variables, p < .001, and a small effect size, rs = .25, meaning that contract length tended to increase along with

minimum required experience.

Figure

5

Part-time

postings by hours of work per week.

Among part-time postings (n = 446) as seen in Figure 5,

the most common assignments of hours per week were 21-34 (33.6%) and 11-20

(24.6%). A substantial portion of postings (30.5%) had variable hours,

indicating on-call work.

Discussion

Overview

The results show that precarious work is substantially

and perhaps even increasingly prevalent in library job postings, with the

percentage of precarious postings on the Partnership Job Board rising

from 39.9% in the first year of data collection to 45.9% in the second year.

The landscape of precarious work varied, with important differences in

prevalence and type of precarity based on the type of institution, type of

position, and the educational or experiential requirements involved.

Results from inferential statistics indicate that while

precarious jobs were prevalent overall, they were not more likely to occur in

one type of library over another. The results show that academic institutions

were more likely to post contract positions than expected, corresponding with

research conducted into sessional and adjunct labour

in academia (Pasma & Shaker, 2018; Foster & Birdsell Bauer, 2019) and showing that libraries are not

immune to academic labour conditions, despite often

being excluded from such studies. Meanwhile, public libraries were more likely

than expected to post for on-call and part-time positions. School libraries saw

the highest prevalence of precarity, while government postings saw the least

overall.

There were significant associations between whether a job

was precarious and the type of position being advertised. Library assistant and

library technician postings were most likely to be precarious, while manager

positions were least likely. These findings indicate that the prevalence of

precarious employment in libraries overall is greater than suggested by

previous research, which mainly focuses on librarian positions held by people

with a MLIS (Mayo & Whitehurst, 2012; Wilkinson, 2016).

Precarity was also strongly associated with the minimum

level of education required for the position. For example, jobs requiring a

secondary diploma or library technician diploma were much more likely than

expected to be precarious than expected, especially in terms of on-call and

part-time work, while jobs requiring MLIS degrees were much less likely than

expected to be precarious.

Looking at minimum required experience, the results also

show significant differences between precarious and non-precarious jobs.

Contract jobs had the highest mean minimum experience at about 24 months, the

lowest mean difference relative to stable jobs at around 13 months, and the

smallest effect size, suggesting that this form of precarity, involving regular

working hours and in many cases full-time employment, requires more experience

than others. By contrast, on-call jobs had the lowest mean minimum experience

at about 16 months, suggesting that the least stable form of precarious work is

also the easiest to get, at least based on experience.

The mean minimum required experience was significantly

higher for stable jobs in all cases, and precarious work was less prevalent

among positions requiring more experience, suggesting that available positions

are less likely to be precarious as people gain more library experience. At the

same time, the mean minimum experience was between one and two years for all

categories of precarious jobs, suggesting that prior work experience is

required even for precarious jobs. This lack of stable, entry-level positions

combined with the amount of minimum experience typically required for all kinds

of positions indicates that people can expect to be precariously employed for

the first few years of their time in libraries.

The uneven distributions among these results suggest that

workers will not experience precarity equally within institutions or across

libraries as a whole. Library employees who are early in their careers without

advanced degrees, or in paraprofessional positions, are more likely to be

working in precarious positions. These employees will therefore be the most

likely to experience the stressors associated with precarity, such as financial

instability, burnout, and poor mental health.

Meanwhile, those in stable positions will be the most

insulated from the effects of precarity, while also having the most power to

affect policy, hiring, retention, and other factors relating to the wellbeing

of precarious colleagues. These positions are most likely for staff in

managerial positions with several years in the field, usually requiring a MLIS or

equivalent.

Limitations

The results of this study may not be fully representative

due to the limitations of job posting analyses as a method. Although collected

data should approach a representative distribution as the sample gets larger,

it is possible that the actual population of jobs is more or less precarious

than observed here. Factors such as the authors’ definition of precarious work,

their decision to code jobs as stable where their status was unclear, the fact

that not all job postings are necessarily filled, and the fact that not all

library jobs are posted to Partnership may all affect the results’

generalizability. Indeed, based on the high prevalence of librarian jobs and

jobs requiring MLIS degrees relative to other kinds of jobs, it is likely that Partnership

is primarily used for library jobs where organizations prefer having nationwide

exposure and paying the listing fee. Other jobs may be distributed internally,

on library websites, or via municipal or provincial job boards, and job categories

such as archivist jobs or government jobs may be posted in still other places.

As a result, there may be a greater or lesser proportion of precarious jobs

than shown in this dataset. Comprehensive data on actual jobs from library

systems, though it would be difficult to gather, could provide a useful

contrast to the data represented here. Finally, it is important to acknowledge

the limitations inherent in a positivist approach. Removing these postings from

the contexts of their creation and circulation and reducing them to categories

in a coding framework will necessarily produce a partial view of precarious

work, with a limited ability to note anything about the material processes that

produce precarious jobs or the people who hold them. Other approaches may

support a more holistic view of this topic. While these limitations should be taken into account, the existing data still points towards

many significant differences and associations, as observed above, and can form

a strong basis for future research.

Future Research

The authors did not conduct analyses combining three or

more variable categories for this article, in order to maintain focus on the

primary research questions and for the sake of brevity. However, further

analysis could investigate specific aspects of precarity, such as differences

in precarity between academic librarians and public librarians, or between

managers with library technician diplomas and managers with MLIS degrees. As

well, researchers could apply methodologies such as content analysis to the

postings collected for this study to determine, for instance, what proportion

of contract positions list the rationales for the contracts, or whether the

ways in which postings list salary ranges varies between precarious and stable jobs.

The authors hope that making their dataset publicly available and archiving the

original postings will help in this regard.

The current findings raise other issues for future

inquiry as well. The distribution of different subtypes of precarity across

institution types may result from different service models, and future research

could seek to determine the causes of precarity within different institution

types. Meanwhile, looking at precarious jobs by education level reveals

disparities based on educational qualifications. The issue of precarity and

non-MLIS positions remains understudied even in comparison to the scant

research on library precarity overall, so further research is needed here too.

This study focused on precarity within the Canadian context, and additional

research could compare levels and distribution of precarity with datasets from

other geographic areas.

The prevalence of precarity among entry-level jobs and

jobs requiring lower levels of education also raises questions about pipeline,

hiring, and retention issues with implications for equity, diversity, and

inclusion in libraries. It is already known that precarious workers are more

likely to be racialized, women, LGBTQ+, or have a disability (Cranford & Vosko, 2006; Bernhardt, 2015; CUPE, 2017). These results

make clear that, whether through education or years of experience, the jobs

that are the most accessible to the most people are also more likely to be

precarious. In the quest for stable jobs, people from historically and presently

marginalized groups must contend with racism, sexism, ableism, homophobia, and

transphobia, in addition to the stresses of precarious work. Given the barriers

to equity, diversity, and inclusion before, during, and after hiring, processes

in the predominantly white library profession’s (Galvan, 2015) precarious

employment structures deserve more attention in relation to these problems.

Conclusion

This study aimed to establish a better understanding of

the prevalence of precarious work and the factors associated with it in

Canadian libraries. The authors collected and coded job postings from a

national job board over a period of two years and conducted statistical

analyses that revealed significant differences in job precarity among different

levels of experience and education, and different types of jobs and

institutions. Contracts and part-time work were the most common types of

precarious employment, with a majority of contracts being for one year or less

and about a third of part-time positions having variable hours. Precarity was

especially prevalent among school libraries, paraprofessional positions,

positions requiring less education, and positions requiring two years of

experience or less. By contrast, it was least evident in government libraries,

managerial positions, positions requiring MLIS or MAS degrees, and positions

requiring three years of experience or more. Precarious jobs also required less

experience on average than stable jobs. These findings show that precarious

work is prevalent in Canadian libraries and that this prevalence varies based

on job characteristics.

References

Bernhardt, N. S. (2015).

Racialized precarious employment and the inadequacies of the Canadian welfare

state. SAGE Open, 5(2), 1-13. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244015575639

Bladek, M. (2019). Contingent appointments in academic

libraries: Management challenges and opportunities. Library Management, 40(8/9),

485-495. https://doi.org/10.1108/LM-06-2019-0032

Canadian Union of Public

Employees. (2017). Employment increasingly precarious in public libraries,

survey finds. In Canadian Union of Public Employees. Retrieved from https://cupe.ca/employment-increasingly-precarious-public-libraries-survey-finds

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power

analysis for the behavioral sciences. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum

Associates. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203771587

Cranford, C. J., & Vosko, L. F. (2006). Conceptualizing precarious employment:

Mapping wage work across social location and occupational context. In L. F. Vosko (Ed.), Precarious

employment: Understanding labour market insecurity in

Canada (pp. 43-66). Montreal and Kingston: McGill–Queen’s University Press.

Ferguson, C. L. (2018).

Electronic resources and serials staffing challenges. Serials Review, 44(2), 122–130. https://doi.org/10.1080/00987913.2018.1471885

Foster, K., & Birdsell Bauer, L. (2018). Out of the shadows: Experiences

of contract academic staff. In Canadian Association of University Teachers.

Retrieved from https://www.caut.ca/sites/default/files/cas_report.pdf

Galvan, A. (2015). Soliciting

performance, hiding bias: Whiteness and librarianship. In the Library with the Lead Pipe. Retrieved from http://www.inthelibrarywiththeleadpipe.org/2015/soliciting-performance-hiding-bias-whiteness-and-librarianship

Gold, M. L., & Grotti, M. G. (2013). Do job advertisements reflect ACRL’s

standards for proficiencies for instruction librarians and coordinators? The Journal of Academic Librarianship, 39(6),

558-565. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2013.05.013

Harper, R. (2012). The

collection and analysis of job advertisements: A review of research

methodology. Library and Information Research,

36(112), 29-54. https://doi.org/10.29173/lirg499

Hartnett, E. (2014). NASIG’s

core competencies for electronic resources librarians revisited: An analysis of

job advertisement trends, 2000–2012. The

Journal of Academic Librarianship, 40(3-4), 247-258. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2014.03.013

Henninger, E., Brons, A., Riley, C., & Yin, C. (2019). Perceptions and

experiences of precarious employment in Canadian libraries: An exploratory

study. Partnership: The Canadian Journal of Library and Information Practice

and Research, 14(2), 1-22. https://doi.org/10.21083/partnership.v14i2.5169

Henninger, E., Brons, A.,

Riley, C., Yin, C. (2020): Precarity in Libraries – Partnership Job Postings. http://doi.org/10.25314/5089ab2f-5583-4675-8484-8446c0d9a701

Henricks, S. A., &

Henricks-Lepp, G. M. (2014). Desired characteristics

of management and leadership for public library directors as expressed in job

advertisements. Journal of Library

Administration, 54(4), 277-290. https://doi.org/10.1080/01930826.2014.924310

Lacey, S. (2019). Job

precarity, contract work, and self-care. Partnership:

The Canadian Journal of Library and Information Practice and Research, 14(1),

1-8. https://doi.org/10.21083/partnership.v14i1.5212

Lakens, D. (2018). Justify your alpha by decreasing alpha

levels as a function of the sample size. In The

20% Statistician. Retrieved from https://daniellakens.blogspot.com/2018/12/testing-whether-observed-data-should.html

Maccaferri, J. T., & Harhai, M. K.

(2019). What Pennsylvania public libraries want: An analysis of PAMAILALL job

advertisements. Pennsylvania Libraries:

Research & Practice, 7(1), 9-24. https://doi.org/10.5195/palrap.2019.201

Maciel, M. L., Kaspar, W. A., & vanDuinkerken, W. (2018). (Desperately) seeking service

leadership in academic libraries: An analysis of dean and director position

advertisements. Journal of Library

Administration, 58(1), 18-53. https://doi.org/10.1080/01930826.2017.1399711

Messum, D., Wilkes, L., Peters, K., & Jackson, D. (2016).

Content analysis of vacancy advertisements for employability skills: Challenges

and opportunities for informing curriculum development. Journal of Teaching and Learning for Graduate Employability, 7(1),

72-86. https://doi.org/10.21153/jtlge2016vol7no1art582

Pasma, C., & Shaker, E. (2018). Contract U: Contract

faculty appointments at Canadian universities. In Canadian Centre for Policy

Alternatives. Retrieved from https://www.policyalternatives.ca/publications/reports/contract-u

Skene, E. (2018). Shooting for

the moon: An analysis of digital initiatives librarian job advertisements. Digital Library Perspectives, 34(2),

84-90. https://doi.org/10.1108/DLP-06-2017-0019

Skyrme, A. E., & Levesque, L. (2019). New librarians and

the practice of everyday life. Canadian

Journal of Academic Librarianship, 5, 1–24. https://doi.org/10.33137/cjal-rcbu.v5.29652

Sproles, C., & Clemons, A.

(2019). The migration of government documents duties to public services: An

analysis of recent trends in government documents librarian job advertisements.

The Reference Librarian, 60(2),

83-92. https://doi.org/10.1080/02763877.2019.1570419

Tewell, E. C. (2012). Employment opportunities for new academic

librarians: Assessing the availability of entry level jobs. Portal: Libraries and the Academy, 12(4),

407-423. https://doi.org/10.1353/pla.2012.0040

Wilkinson, Z. T. (2015). A

human resources dilemma? Emergent themes in the experiences of part-time

librarians. Journal of Library

Administration, 55(5), 343-361. https://doi.org/10.1080/01930826.2015.1047253

Wilkinson, Z. (2016). A review

of advertisements for part-time library positions in Pennsylvania and New

Jersey. Library Management, 37(1/2),

68-80. https://doi.org/10.1108/LM-08-2015-0054

Wise, S., Henninger, M., &

Kennan, M. A. (2011). Changing trends in LIS job advertisements. Australian Academic & Research

Libraries, 42(4), 268-295. https://doi.org/10.1080/00048623.2011.10722241

Appendix

Coding Fields, Categories, and Criteria for Job Postings

|

Field |

Categories |

Notes |

|

Job Type |

Archivist,

assistant, librarian, manager, technician, other |

Archivist =

positions requiring a MAS or equivalent Assistant =

positions using language such as assistant, associate, or clerk, typically

not requiring library-specific credentials Librarian =

positions requiring an MLIS or equivalent Manager =

positions with direct supervisory responsibilities requiring any kind of

degree Technician =

positions requiring a library technician diploma or equivalent Other =

positions not fitting any of the above categories |

|

Institution

Type |

Academic, government,

public, school, other |

Positions were

coded according to the kinds of institutions in which they were based. |

|

Part-Time |

Full-time,

part-time |

Positions

specifying 35 or more weekly hours were coded as ‘full-time,’ while those

specifying fewer were coded as ‘part-time.’ Positions that did not specify a

number of hours and were not coded as on-call were assumed to be full-time. |

|

Number of

Hours |

1-10, 11-20,

21-30, 35+, variable, not specified. |

Positions were

further broken down based on ranges of hours worked. Full-time jobs were

assumed to be 35+ hours, and part-time jobs that did not specify hours were

coded as ‘not specified.’ |

|

On-Call |

Regular,

on-call |

Positions that

explicitly used language such as auxiliary, casual, on-call, and occasional,

as well as postings which explicitly stated varying schedules and hours of

work, were coded as ‘on-call.’ |

|

Contract |

Ongoing,

contract |

Positions that

explicitly used language such as contract, term-limited, sessional, and

temporary were coded as ‘contract.’ |

|

Contract

Duration (Months) |

[number of

months], not specified |

Coded based on

the posting. Duration was rounded to the nearest full month for durations

expressed in weeks or specific date ranges. Postings listing contracts as

lasting ‘up to’ a period of time were coded as lasting the maximum duration.

Contracts that did not specify duration were coded as ‘not specified.’ |

|

Precarious? |

Yes, no |

Any position

coded as on-call, contract, or part-time was coded as ‘yes.’ |

|

Education

Level |

Library

technician diploma or equivalent, MAS or equivalent, MLIS or equivalent, MLIS

or library technician diploma, other postsecondary degree, secondary diploma,

some library coursework, not specified, other |

Coded based on

the minimum educational level required in the posting. Postings that did not

require a specific educational status were coded as ‘not specified.’ |

|

Minimum

Experience (Months) |

[number of

months], not specified |

Coded based on

the posting. Postings that required experience ‘up to’ a certain amount were

coded as 0 months since there was explicitly no lower bound. Postings that

did not specify minimum required experience were coded as ‘not specified.’ |