Research Article

Occupational Stress and Job Performance Among

University Library Professionals of North-East India

Pallabi

Devi

Research Scholar

Dept. of Library &

Information Science

Gauhati

University

Guwahati, Assam, India

Email: devipallabi.pd@gmail.com

Prof. Narendra Lahkar

Former Professor & Head

Dept. of Library and

Information Science

Gauhati

University

Guwahati, Assam, India

Email: nlahkar@gmail.com

Received: 17 Aug. 2020 Accepted: 9 Mar. 2021

![]() 2021 Devi and Lahkar. This is an Open

Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

2021 Devi and Lahkar. This is an Open

Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

DOI: 10.18438/eblip29821

Abstract

Objective – The

present study intends to investigate the occupational stress and job

performance of university library professionals in North-East India. The main

objective of the study is to assess the perceived level of occupational stress

among library professionals and to identify any relationship between

occupational stress and library professionals’ job performance. The study also

aims to study gender differences regarding perceived occupational stress and

job performance among library professionals as well as examine the influence of

occupational stress on perceived job performance.

Methods

– Descriptive survey method was used for

the study. The sample population consisted of 123 library professionals from

different parts of North-East India selected through convenience sampling

technique. The survey consisted of a structured questionnaire divided into

three sections: demographic information, self-perceived occupational stress,

and self-rated job performance. Descriptive and inferential statistical

techniques including frequency, mean, standard deviation, t test,

correlation co-efficient, and simple linear regression analysis were used to

analyze data and interpret results with the help of the statistical package

SPSS version 20.

Results

– The findings of the study established

that a majority of library professionals working in university libraries of

North-East India perceived a moderate level of occupational stress. It was also

determined that male and female library professionals do not differ in their

perception of occupational stress (p > 0.05), while a significant

mean difference was found between male and female library professionals’

perceptions towards their job performance (p < 0.05). Males scored themselves higher than

females in terms of eight indicators of job performance: quality of work

performance, ability to handle multiple jobs, communication skills, decision

making, problem solving, technical skills, ability to perform competently under

pressure, and contribution to the overall development of the library. Regarding

the relationship between occupational stress and job performance, the data

indicated a significant negative relationship between occupational stress and

job performance (r = -0.296, p

< 0.01). In addition to this,

intrinsic impoverishment, under participation, low status, and poor peer

relationships were some of the factors negatively affecting the job performance

of library professionals.

Conclusion

–

The present study provides an insight about how occupational stress affects job

performance of library professionals working in academic libraries. The findings revealed that there

exists a modest but statistically significant negative relationship between

occupational stress and job performance, which implies that an increment in the

level of perceived occupational stress tends to influence library

professionals’ self-perception of job performance negatively.

Introduction

Stress

is a “perceived phenomenon associated with tension and anxiety. One is

considered as being under stress when a situation is perceived as presenting an

extra demand on the individual’s capabilities and resources” (Nawe, 1995, p. 30). Most often, stress can be defined:

As

a way a human body reacts to stimuli from the environment; it can influence

one’s psychological and physical condition. Experiencing lower levels of stress

can be stimulating, but being exposed to higher levels of stress for long

periods of time may affect one’s health and cause negative emotions, feelings

of pressure, anxiety, irritability, loss of appetite, and others, and finally

bad performance at work. (Petek, 2018, p. 129)

Research

has shown that stress in general exists in different forms; it may be

psychological, emotional, social, occupational, or job related. Over the past

few decades, occupational stress, or job stress, has been emerging as a growing

concern because we spend a lot of time at the workplace. Blix et al. (1994)

stated that “occupational stress is considered to be one of the ten leading

work-related health problems” (p. 157). According to Kaur and Kathuria (2018):

Occupational

stress is a mental or physical tension or both, created and related to

occupation and its environment which comprise of persons and objects from

within and outside the work place resulting into absenteeism, lack of

motivation and initiative, low productivity and service efficiency, job

dissatisfaction and disruption of the smooth functioning of the organization.

(p. 13)

Employees’

efficiency in the organization is evidenced in terms of their performance at

the workplace. Job performance is an important criterion for organizational outcomes

and success. Ojo (2009) defined job performance as an

extent to which the day-to-day work is being carried out. Job performance can

be defined as individual productivity in terms of both quantitative and

qualitative aspects of the job. It indicates how well a person is performing

their job and to what extent, the employee is able to meet their job duties as

well as policies and standards of the organization.

Several

studies have pointed out that there are emerging issues in the library and

information science profession that poses a threat or stress factor to library

professionals, especially the academic librarians. These include “new

expectations and the constantly changing role of librarians due to the dynamic

nature of information and its delivery in the university system, triggered by

the emergence of ICT in the library and information practice” (Ajala, 2011, para. 2). Reena (2009) further supported this

by averring that one of the

realities of 21st century is that the library professionals are faced with

constant challenges in their working environments. This is not only because of

the role they have to play inside the libraries but also due to the increasing

demands and expectations of the users within the libraries.

Moreover, as said by Saqib Saddiq, librarians were mostly unhappy with their workplace,

often finding their job repetitive and unchallenging. They complained about

their physical environment, saying that they were sick of being stuck between

bookshelves all day as well as claiming that their skills were not used and

that they felt they had very little control over their career (“Librarians ‘suffer most stress’,” 2006).

According to Topper (2007), after years of doing the same tasks can be

stressful and many librarians may feel that they are not being challenged in

their work.

Statement of the Problem

The university library constitutes a vital element in

any academic institution, and hence library professionals play a significant

role in promoting teaching, learning, and research by providing information

sources and services to students, researchers, and faculty. Library staff

should be concerned about the needs of the library users so that optimum

utilization of the resources available can be achieved. The library staffs are

the facilitators for the contact between users and resources. The work of the

library professionals in service delivery is a key element that contributes to

overall effectiveness of the organization. In extending their services as much

as possible, stress should not be a hurdle in enacting efforts to serve the

user community. Research has already established that a high level of

occupational stress may lead to a high level of dissatisfaction among the

employees, a lack of job mobility, burnout, poor work performance, and less

effective interpersonal relations at work (Manshor et

al., 2003).

Gender is another variable that can potentially affect

the attitudes and perceptions of employees at the workplace. A few studies have

already asserted that though the library profession is open for all genders, it

is mostly female (Carmichael, 1992; Wiebe, 2004). “Although librarianship is a

female-dominated profession, both males and females within the profession

suffer from work-related pressures based on the practices of gender bias”

(Greer et al., 2001, p. 127). Several studies have shown that some

differences exist in the level of dissatisfaction between male and female

library staff. Graddick and Farr (1983), for example,

pointed out that females often view themselves as being treated worse than

males in the workplace. Kirkland (1997) argued that most of the women in

libraries suffer from a deprivation of inside information, challenging

assignments, and recognition in their organizations. Thus, several studies have

discussed the gender-related issues of different aspects of work, but very few

empirical studies directly examine gender-based differences among library

employees’ perceptions regarding occupational stress and job performance at the

university level.

It is in the light of these problems that the present

study seeks to gain an insight on how occupational stress affects job

performance of library professionals working in university libraries of

North-East India. The study also attempts to explore gender differences among

library professionals in their perceptions of occupational stress and their own

job performance.

Scope and Limitation of the Study

The study limits itself to measuring the perceived

level of occupational stress and examining the relationship between perceived

occupational stress and self-rated job performance of university library

professionals in North-East India. The libraries attached to eight central

universities, four state universities, and one Institution of National

Importance located in various states of North-East India were picked up for the

study. It should be noted that, North-East India is made up of total eight

states: Assam, Arunachal Pradesh, Meghalaya, Sikkim, Manipur, Mizoram,

Nagaland, and Tripura. The geographical coverage of the study includes only

Assam, Arunachal Pradesh, Meghalaya, Sikkim, Manipur, and Tripura. The newly

established universities including private universities are excluded from the

study because these institutions are still in their infancy.

Literature Review

Numerous bodies of literature have explored stress

from different perspectives in different organizational settings and

highlighted various stressors related to those situations. Stress can be caused

by many problems, such as problems at the workplace, financial problems, family

problems, and problems in employees’ surroundings.

The Health and Safety Executive (HSE, 2001) defined

stress as an adverse reaction to excessive or extreme pressures or demands that

may be placed upon individuals. The pressure and demands that causes stress are

known as stressors. According to Hinkle (1974), the term stress denoted “force,

pressure, strain or strong effort” exerted upon a material object or a person

or upon a person’s “organs or mental powers” (p. 337). In this definition,

individuals were acted upon by external forces.

Occupational stress or work-related stress arises when

work demands of various types and combinations exceed the person’s capacity and

capability to cope with it. Somvir and Kaushik (2013)

investigated occupational stress among library professionals in Haryana state

and reported that most of the librarians were frustrated because they were

compared with clerical staff and had to work under the in-charge of a

non-professional, who did not know about the duties and responsibilities of

being a librarian. Low salary, less freedom to make decisions related to

budget, responsibility for loss of books, technological changes, and a lack of

interaction among library professionals were some of the factors discouraging

librarians to provide better library services. Ratha

et al. (2012) highlighted that workload,

technology, shift work, user satisfaction, job insecurity, lack of

administrative support, low status, inadequate salary, changing library

environment, and reduced staff strength were some of the leading causes of

occupational stress among library professionals in private engineering colleges

in Indore City. Mahanta (2015) carried out a study to determine the sources of

stress and magnitude of stress among the library professionals of Central

Library, Tezpur University, Assam. The researcher found that the library

employees in the study experienced organizational role stress to a moderate

extent. The study identified that role ambiguity, inter-role distance, role

stagnation, and role erosion were the powerful sources of stress among the

library staff. In fact, role conflict, role ambiguity, and role overload have

also been studied as antecedents of occupational stress (Brief & Aldag, 1976; Ivanceyich et al.,

1982).

Gender seems to play a significant role in employees’

perception of work-related stress and job performance. Jick

and Mitz (1985) stated that workplace stress is a

major problem and suggested that gender may be considered an important demographic

characteristic in the experience of stress. Mosadeghrad

(2014) revealed in his study that there was a strong correlation between the

occupational stress of hospital employees and their gender. Female employees

reported higher occupational stress than their male colleagues. Dina (2016)

found that women suffered from stress more frequently than men owing to their

dual responsibilities including work in the library and taking care of children

or parents at home. Oloruntoba and Ajayi (2006) found

that most male academic librarians have higher job performance than their

female colleagues. Oyeniran and Akphorhonor (2019) stated that male librarians

working in the university libraries in Nigeria contributed more than their

female counterpart in terms of performance. The gender difference had a

positive influence on the job performance of librarians in the university

libraries in Nigeria.

Much of the earlier literature on occupational stress

emphasizes its effects on job performance. Ali et al. (2011) found that there exists a highly

significant positive relationship between job stress and job performance among

banking employees (i.e., job performance was found to be better under stressful

situations at workplace). In addition, all the three indicators of job performance—skills,

efforts, and working conditions—had a positive direct relationship with job

stress. Conversely, Ahmed and Ramzan (2013) reported the existence of a

significant negative relationship between job stress and job performance in the

banking sector, which implied that both variables were inversely proportional

to each other. When job stress was low, job performance increased, and when job

stress was high, job performance decreased.

Dina (2016) carried out a study to investigate the

impact of stress on professional librarian’s job performance in Nigerian

University libraries. The findings showed that high amounts of stress can

affect a professional librarians’ quality in terms of job performance in

relation to their job demands and expectations. Those professional librarians

engaged in other activities besides their primary assignments for which they

are employed were found more likely to be stressed than the others thereby

affecting their job performance negatively. Occupational stress was identified

as one of the major problems impacting professional librarians’ wellbeing,

commitment, and job performance.

Kaur and Kathuria (2018) conducted a study among 301 library

professionals working in central libraries of 24 universities in Punjab and Chandigarh.

The study revealed that occupational stress and job performance shared a

negative but significant co-efficient of correlation with each other, which

implies that as the level of occupational stress increased, the level of job

performance decreased. Ilo et al. (2019) investigated

the relationship between job stress and job performance in university libraries

in Nigeria. The study identified low productivity, increased absenteeism,

hypertension, job dissatisfaction, frustration, depression, and negative job

attitude as negative effects of stress on the job performance of librarians. Amusa et al. (2013) revealed

in their study that a significant correlation exists between the work

environment and job performance of librarians. Moreover, the study highlighted

that the librarians’ job performance was considered fair with regard to

variables such as professional practice, contribution to the overall

development of the library, ability to attend promptly to client’s request, and

meeting minimum requirements for job promotion.

In summary, after reviewing all the relevant studies,

occupational stress clearly exists in academic library environments and some of

the common stressors affecting maximum the number of library employees include

role overload, role conflict, role ambiguity, low status, lack of

administrative support, and changing library environment. Both occupational

stress and job performance were found to be interrelated with each other, which

imply that higher levels of occupational stress are related to lower levels of

job performance and vice-versa. Gender proved to be one of the significant

factors influencing both occupational stress and job performance.

Aims

The aims of the present study are presented here:

- To assess

the perceived level of occupational stress among library professionals

working in university libraries of North-East India.

- To study

the gender differences regarding perceived occupational stress and job

performance among the library professionals.

- To identify

the relationship between occupational stress and job performance.

- To examine

the impact of occupational stress on job performance.

Hypotheses of the Study

Based on the aims of the study, the following null

hypotheses were formulated:

- H0 –

There is no significant difference between male and female library

professionals regarding perceived level of occupational stress.

- H01 –

Male and female library professionals do not differ in their perception of

job performance.

- H02 –No significant relationship exists between occupational stress and

job performance.

- H03 – There is no significant impact of occupational stress on job

performance.

Methods

The Population

A descriptive survey method was employed to collect

primary data from library professionals who work full time and who have a

minimum qualification of a Diploma in Library & Information Science in

different universities of North-East India that were recognized by the

University Grants Commission (UGC) of India. Convenience sampling technique was

used to gather data from a sample population of 123 library professionals who

were easily available as well as willing to participate in the study from

various states of North-East India. The breakdown of the sample population is

given in Table 1.

Research Instrument

A structured questionnaire was constructed in print

and distributed personally to the participants, making quantitative data

relatively easy to collect. The questionnaire was divided into three sections:

demographic information, self-perceived occupational stress, and self-rated job

performance. To measure the level of perceived occupational stress, we designed

an Occupational Stress Scale that was adapted from the Occupational Stress Index (OSI) of Srivastava and Singh (1984) and

the Organisational Role Stress (ORS)

Scale of Pareek (1983). The OSI scale, a widely used scale in

India was adopted by Ratha et al. (2012) and Chandraiah

et al. (2003) in their studies. Similarly, the ORS scale, which is

more specifically used in Indian socio-cultural settings, was used by Mahanta

(2015) and Jena and Pradhan (2011) in their research studies. Reena (2009) used

both the OSI and ORS scales in order to construct an instrument especially

useful for the library and information science profession. The scale used in the study consists of a

total of 23 items on 11 dimensions of occupational stress: role overload, role

conflict, role ambiguity, under participation, low status, poor peer

relationship, personal inadequacy, strenuous working conditions, career

stagnation, intrinsic impoverishment, and unreasonable groups & political

pressures. Brief descriptions of the dimensions of occupational stress

used in the context of present study are stated here:

- Role overload arises when employees feel pressured because of added duties and

responsibilities and lack the resources to perform them.

- Role conflict refers to situations with conflict of role expectations.

- Role ambiguity refers to a situation caused

by lack of clarity or understanding about job expectations and

responsibilities in the performance of a particular role.

- Under participation is when there is a lack

of one’s influence on the decision-making process of the organization.

- Low status refers to a state of

insignificance in the organizational as well as in the social system.

- Poor peer relationship occurs when there is lack of mutual co-operation

between coworkers in solving organizational

problems.

- Personal inadequacy refers to employees lacking the required skills to perform tasks

expected to function within their roles.

- Strenuous working conditions refers to a lack of comfort and safety in the

work environment.

- Career stagnation occurs when a employees feel a lack of

engagement with their work or career.

- Intrinsic impoverishment refers to monotonous nature of assignments, lack

of ample opportunity to utilize one’s abilities and develop one’s

aptitude, etc.

- Unreasonable group and political pressure evolve from a

situation where one is required to take a lot of decisions against his

will or against formal rules and procedures under pressure.

Table

1

Breakdown

of the Sample Population

|

Type

of University |

No.

of Universities Surveyed |

No.

of Respondents |

|

State Universities |

4 |

33 |

|

Central Universities |

8 |

79 |

|

Institution of National Importance |

1 |

11 |

|

Total |

13 |

123 |

Table

2

Descriptive Statistics of Occupational Stress and Job

Performance

|

Variable |

N |

Minimum Score |

Maximum Score |

Mean |

Standard Deviation |

|

Occupational

Stress |

123 |

40 |

85 |

60.91 |

9.069 |

|

Job

Performance |

123 |

40 |

70 |

59.02 |

6.968 |

Responses on all items were

gathered through a five-point Likert scale (Strongly Agree = 5, Agree = 4,

Disagree = 3, Strongly Disagree = 2, and Undecided = 1). The Cronbach’s Alpha

Coefficient of Reliability was computed to verify the internal consistency of

items used to measure a variable which was found to be .744. Nunnally (1978) recommended at least .70 alpha

coefficients for social sciences as acceptable.

Similarly, to measure job performance, a

self-assessment “Job Performance Scale” was constructed that consists of a

total of 14 job performance indicators (including completion of tasks on a

given time, quality of work performance, ability to handle multiple jobs,

communication skills, decision making, problem solving, technical skills,

managerial skills, ability to perform competently under pressure, punctuality

and regularity at work, meeting minimum requirements for promotion,

interpersonal relationship with co-workers, contribution to the overall

development of the library, and overall capacity to work) rated on a five-point Likert scale (Very Good

= 5, Good = 4, Average = 3, Poor = 2, and Very Poor = 1). The purpose of

designing the scale was to gather input from the library professionals about

their self-perception of how well they are performing their job. The

reliability coefficient of the scale was found to be .905 using Cronbach’s

alpha method. Statistical techniques like frequency, mean, standard deviation, t

test, correlation co-efficient, and simple linear regression analysis were used

to analyze the data and interpret the results with the help of the statistical

package SPSS version 20. The descriptive statistics of the two variables

selected for the study, i.e., occupational stress and job performance, are

presented in Table 2.

Table 2 reflects that the mean and standard deviation

of the total scores of perceived occupational stress is 60.91 and 9.069

respectively, whereas the mean and standard deviation of the total scores of

self-rated job performance is calculated to be 59.02 and 6.968 respectively.

The overall score ranges from a minimum of 40 to a maximum of 85 in the case of

perceived occupational stress while the job performance scores ranges from a minimum

of 40 to a maximum of 70. The table shows that the mean of both variables

(i.e., occupational stress and job performance) seems to be identical; however,

the range of scores was found to be greater in the case of occupational stress.

Results

The results and their analysis are presented here and

keeping in mind the aims of the study.

Demographic Information

The demographic data collected are presented in Table

3 and describe the demographic

characteristics of the sample population.

The demographic profile of the respondents in the

present study demonstrated that with respect to responses on gender, 77

(62.60%) respondents were males while 46 (37.39%) were females. In response to

age distribution, the highest number of respondents (35.77%) belongs to the age

group of 31 to 40 years, which indicates a youthful working class. Table 3 also

shows that a majority of the respondents (55.28%) hold master’s degrees as

their highest professional qualification and a plurality (45.52%) had work

experience of above 15 years.

Perceived Levels of Occupational Stress

In order to assess the

perceived levels of occupational stress, the Mean (x) and Standard Deviation (SD)

of the total scores of occupational stress obtained

from the sum of the responses of all respondents were considered.

Therefore, the total scores of occupational stress

were divided into three categories on the basis of their x and SD.

Following the principles of normal distribution, the scores falling above or

equal to x

+ SD, between x + SD and x – SD, and below

or equal to x – SD were categorized as high level, moderate

level, and low level, respectively.

Level of Occupational

Stress

·

High level = Above or equal to 70

·

Moderate level = Between 52 and 70

·

Low level = Below or equal to 52

Table

3

Demographic

Profile of the Respondents

|

Demographic Variables |

Frequency (n =

123) |

Percentage (%) |

|

|

Gender |

Male |

77 |

62.60 |

|

Female |

46 |

37.39 |

|

|

Age Group (in years) |

21–30 |

12 |

9.75 |

|

31–40 |

44 |

35.77 |

|

|

41–50 |

34 |

27.64 |

|

|

51–60 |

33 |

26.82 |

|

|

Highest Professional Qualification |

Ph.D. |

23 |

18.69 |

|

M.Phil. |

8 |

6.50 |

|

|

Master’s

Degree |

68 |

55.28 |

|

|

Bachelor’s

Degree |

16 |

13.00 |

|

|

Certificate/Diploma |

8 |

6.50 |

|

|

Years of Work Experience |

0–5 |

19 |

15.44 |

|

6–10 |

36 |

29.26 |

|

|

11–15 |

12 |

9.75 |

|

|

Above

15 |

56 |

45.52 |

|

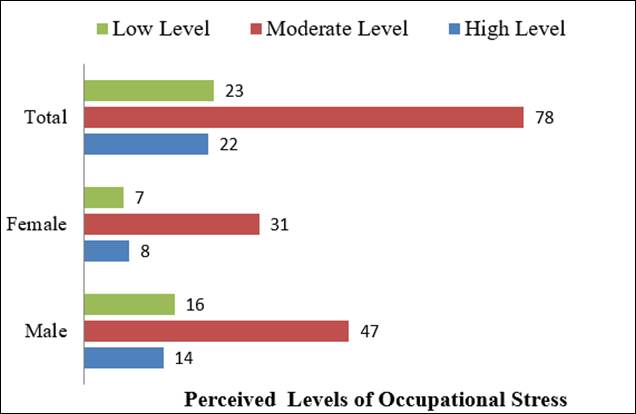

Both Table 4 and Figure 1 depict that a majority of

library professionals surveyed perceived a moderate level of occupational

stress (i.e., 63.41%), which consists of 47 males and 31 females. Of the

remaining library professionals, 18.69% perceived a low level of stress and 17.88%

experienced a high level of occupational stress.

Gender Differences with Regard to

Perceived Occupational Stress

The results in Table 5 clearly depict that t value for mean difference in

occupational stress between male and female library professionals is -0.741,

which is not significant (p

> 0.05). The overall mean and standard deviation of male and female library

professionals are found to be 60.44 (SD

= 9.372) and 61.70 (SD = 8.581)

respectively regarding their perceived level of occupational stress. This

implies that the male and female library professionals working in university

libraries do not differ in their perception of occupational stress. Thus, the

null hypothesis (H0)

is accepted. The dimension-wise comparative analysis between male and female

library professionals in terms of perceived occupational stress is presented in

Table 6.

Table

4

Perceived

Levels of Occupational Stress Among Library Professionals

|

Levels |

Levels |

N |

(%) |

Gender |

N |

(%) |

|

Occupational Stress |

High Level |

22 |

17.88 |

Male |

14 |

63.63 |

|

Female |

8 |

30.43 |

||||

|

Moderate Level |

78 |

63.41 |

Male |

47 |

60.25 |

|

|

Female |

31 |

39.74 |

||||

|

Low Level |

23 |

18.69 |

Male |

16 |

69.56 |

|

|

Female |

7 |

30.43 |

Figure

1

Perceived

levels of occupational stress.

Table

5

Significance

of Mean Difference in Perceived Occupational Stress of Library Professionals

Between Male and Female

|

Variable |

Gender |

N |

Mean |

Standard Deviation |

t value |

p value |

|

Occupational Stress |

Male |

77 |

60.44 |

9.372 |

-0.741 |

0.460 |

|

Female |

46 |

61.70 |

8.581 |

Table

6

Comparative

Analysis Between Male and Female Library Professionals in Terms of Occupational

Stress Dimensions

|

Dimensions of

Occupational Stress |

Gender |

N |

Mean |

Standard Deviation |

t value |

p value |

|

Role Overload |

Male |

77 |

9.60 |

1.982 |

0.743 |

0.459 |

|

Female |

46 |

9.33 |

1.921 |

|||

|

Role Conflict |

Male |

77 |

2.99 |

0.939 |

-0.184 |

0.854 |

|

Female |

46 |

3.02 |

1.125 |

|||

|

Role Ambiguity |

Male |

77 |

4.75 |

1.425 |

-0.455 |

0.650 |

|

Female |

46 |

4.87 |

1.276 |

|||

|

Low Status |

Male |

77 |

4.47 |

1.586 |

-0.377 |

0.707 |

|

Female |

46 |

4.59 |

1.881 |

|||

|

Under Participation |

Male |

77 |

5.10 |

2.043 |

-0.754 |

0.452 |

|

Female |

46 |

5.39 |

2.049 |

|||

|

Poor Peer

Relationship |

Male |

77 |

7.71 |

1.891 |

0.053 |

0.958 |

|

Female |

46 |

7.70 |

1.860 |

|||

|

Personal

Inadequacy |

Male |

77 |

5.86 |

1.457 |

0.120 |

0.905 |

|

Female |

46 |

5.83 |

1.270 |

|||

|

Career

Stagnation |

Male |

77 |

3.01 |

1.082 |

-0.257 |

0.798 |

|

Female |

46 |

3.07 |

1.104 |

|||

|

Strenuous

Working Conditions |

Male |

77 |

10.13 |

2.232 |

-0.882 |

0.380 |

|

Female |

46 |

10.50 |

2.288 |

|||

|

Intrinsic

Impoverishment |

Male |

77 |

4.45 |

1.667 |

-1.717 |

0.088 |

|

Female |

46 |

5.02 |

1.938 |

|||

|

Unreasonable

Groups & Political Pressures |

Male |

77 |

2.36 |

0.872 |

-0.180 |

0.858 |

|

Female |

46 |

2.39 |

0.745 |

Gender Differences with Regard to

Perceived Job Performance

Table 7 reveals that the t value for the mean difference in terms of job performance

between male and female library professionals is 3.163 (p < 0.05). There exists a significant mean difference in

library professionals’ perception of job performance based on their gender. The

overall mean and standard deviation of male and female library professionals

are found to be 60.51 (SD =

6.522) and 56.54 (SD = 7.051)

respectively. Since the mean score of male library professionals is greater

than their female counterpart, we can derive that the male library

professionals perceived their level of job performance as better compared to

the female library professionals. Thus, the null hypothesis (H01) is rejected. Table 8

shows the comparative analysis between male and female library professionals in

terms of their self-perception towards job performance indicators.

From Table 8, we can observe a statistically

significant difference between the mean scores of male and female library

professionals with regard to eight indicators of job performance: quality of

work performance, ability to handle multiple jobs, communication skills,

decision making, problem solving, technical skills, ability to perform

competently under pressure, and contribution to the overall development of the

library. The mean score of male library professionals is greater than their

female counterpart in terms of these eight indicators of job performance.

Hence, it indicates that the male library professionals had a better

self-perception than the female library professionals in the case of quality of

work performance, ability to handle multiple jobs, communication skills,

decision making, problem solving, technical skills, ability to perform competently

under pressure, and contribution to the overall development of the library.

Table

7

Significance

of Mean Difference in Perceived Job Performance of Library Professionals

Between Male and Female

|

Variable |

Gender |

N |

Mean |

Standard Deviation |

t value |

p value |

|

Job Performance |

Male |

77 |

60.51 |

6.522 |

3.163 |

0.002* |

|

Female |

46 |

56.54 |

7.051 |

*Significant at 0.05 level (2-tailed)

Table

8

Comparative

Analysis Between Male and Female Library Professionals in Terms of Job

Performance Indicators

|

Indicators of Job Performance |

Gender |

N |

Mean |

Standard Deviation |

t value |

p value |

|

Completion

of Tasks on a Given Time |

Male |

77 |

4.49 |

0.620 |

1.035 |

0.303 |

|

Female |

46 |

4.37 |

0.679 |

|||

|

Quality

of Work Performance |

Male |

77 |

4.47 |

0.575 |

2.306 |

0.023** |

|

Female |

46 |

4.22 |

0.593 |

|||

|

Ability

to Handle Multiple Jobs |

Male |

77 |

4.40 |

0.712 |

2.326 |

0.022** |

|

Female |

46 |

4.09 |

0.755 |

|||

|

Communication

Skills |

Male |

77 |

4.26 |

0.715 |

2.333 |

0.021** |

|

Female |

46 |

3.93 |

0.800 |

|||

|

Decision

Making |

Male |

77 |

4.09 |

0.747 |

2.501 |

0.014** |

|

Female |

46 |

3.72 |

0.886 |

|||

|

Problem

Solving |

Male |

77 |

4.26 |

0.637 |

3.348 |

0.001* |

|

Female |

46 |

3.85 |

0.698 |

|||

|

Technical

Skills |

Male |

77 |

4.27 |

0.719 |

3.816 |

0.000* |

|

Female |

46 |

3.74 |

0.801 |

|||

|

Managerial

Skills |

Male |

77 |

3.92 |

0.900 |

1.100 |

0.274 |

|

Female |

46 |

3.74 |

0.880 |

|||

|

Ability

to Perform Competently Under Pressure |

Male |

77 |

4.10 |

0.836 |

3.307 |

0.001* |

|

Female |

46 |

3.57 |

0.935 |

|||

|

Punctuality

and Regularity at Work |

Male |

77 |

4.64 |

0.605 |

1.615 |

0.109 |

|

Female |

46 |

4.46 |

0.585 |

|||

|

Meeting

Minimum Requirements for Promotion |

Male |

77 |

4.06 |

0.978 |

1.053 |

0.294 |

|

Female |

46 |

3.87 |

1.024 |

|||

|

Interpersonal

Relationship With Coworkers |

Male |

77 |

4.52 |

0.641 |

0.749 |

0.455 |

|

Female |

46 |

4.43 |

0.544 |

|||

|

Contribution

to the Overall Development of the Library |

Male |

77 |

4.56 |

0.573 |

2.243 |

0.027** |

|

Female |

46 |

4.30 |

0.662 |

|||

|

Overall

Capacity to Work |

Male |

77 |

4.45 |

0.527 |

1.765 |

0.080 |

|

Female |

46 |

4.26 |

0.681 |

*Significant at 0.01 (2-tailed) level; **Significant

at 0.05 (2-tailed) level

Table

9

Correlation

Between Occupational Stress and Job Performance

|

Variables |

Occupational Stress |

Job Performance |

|

|

Occupational

Stress |

Pearson

Correlation Sig.

(two-tailed) N |

1 123 |

-0.296** 0.001 123 |

|

Job

Performance |

Pearson

Correlation Sig.

(two-tailed) N |

-0.296** 0.001 123 |

1 123 |

**Correlation

is significant at the 0.01 level (two-tailed).

Relationship

Between Occupational Stress and Job Performance

Karl Pearson’s coefficient

of correlation was used to investigate the relationship between occupational

stress and job performance in totality as well as through eleven dimensions of

occupational stress. The level of significance of coefficient of correlation

was calculated through two-tailed significant value.

A highly significant

relationship was found from the above analysis between occupational stress and

job performance through Karl Pearson’s coefficient of correlation, which means

that the correlation is significant at 0.01 level. The results from Table 9

reveals that there is a negative relationship that proves to be significant (p

< 0.01) between occupational stress and job performance of library

professionals (r = -0.296). Hence the null hypothesis (H03)

is rejected.

The objective of identifying

the relationship between occupational stress and job performance of library

professionals was further studied by focusing on the relationship of each

dimension of occupational stress with job performance. Table 10 demonstrates

dimension-wise values of coefficient of correlation. It is evident from the

table that intrinsic impoverishment has the strongest value of coefficient of

correlation (r = -0.352) followed by under participation (r =

-0.331), low status (r = -0.242), and poor peer relationship (r =

-0.188). The remaining seven dimensions of occupational stress (role overload,

role conflict, role ambiguity, personal inadequacy, career stagnation,

strenuous working conditions, and unreasonable groups & political

pressures) have shown no correlation with job performance. This means that the

library professionals working in university libraries moderately experiencing

these seven dimensions of occupational stress are not likely to bear a definite

effect of it on their job performance.

Table 10

Relationship Between Dimensions of Occupational

Stress and Job Performance

|

Dimensions

of Occupational Stress |

Coefficient

of Correlation (r) |

|

Role Overload |

-0.005 |

|

Role Conflict |

-0.051 |

|

Role Ambiguity |

-0.133 |

|

Low Status |

-0.242** |

|

Under Participation |

-0.331** |

|

Poor Peer Relationship |

-0.188* |

|

Personal Inadequacy |

-0.096 |

|

Career Stagnation |

-0.087 |

|

Strenuous Working Conditions |

-0.054 |

|

Intrinsic Impoverishment |

-0.352** |

|

Unreasonable Groups &

Political Pressures |

-0.036 |

*Correlation is significant at

the 0.05 level (two-tailed)

**Correlation is significant at

the 0.01 level (two-tailed)

Impact of Occupational Stress on Job Performance

Simple linear regression analysis was chosen to

determine whether there is significant impact of occupational stress on job

performance of library professionals working in university libraries. The

present study was conducted to find out any association between the two

variables selected (i.e., occupational stress and job performance). In this

case, occupational stress was used to predict the dependent variable job

performance. No doubt, there may be other parameters or factors affecting job

performance that are not presented in the study because of its limitations. The

value of R2 is found to be 0.088, which means that 8.8% of

the variance in job performance can be explained by occupational stress.

Furthermore, the value of F = 11.629 (1,121) with significance level of p

= 0.001 determined the linear regression model as statistically significant.

The criterion to assess the contribution of the

predictor variable given by Cohen (1988) was used in this study. According to

this source, for linear regression models in behavioural sciences, the

proportion of variance explained by the predictor variable an R2

value between 2% and 12.99% suggests a small effect size, a value between 13%

and 25.99% indicates a medium effect size, and a value of 26% and greater

suggests a large effect size. Since the correlation coefficient in the present

study is -0.296 and the R2 value is equal to 8.8% variance,

the independent variable—occupational stress—is having a small but

significant impact on the dependent variable job performance in a negative

manner. From Table 11, we can observe that occupational stress is able to explain

the variance in job performance by the B value of -0.227. Since the sign of

regression coefficient value is negative, it indicates that as occupational

stress increases by one unit, job performance decreases by 0.227 units.

Therefore, the null hypothesis (H04) is rejected.

Table 11

Simple Linear Regression Analysis Between

Occupational Stress and Job Performance

|

Dependent Variable |

Independent Variable |

Unstandardized Coefficients |

Standardized Coefficients |

t |

Sig. |

|

|

B |

Std. Error |

Beta |

||||

|

Job

Performance |

(Constant) Occupational

Stress |

72.882 -0.227 |

4.108 0.067 |

-0.296 |

17.741 -3.410 |

0.000 0.001 |

|

R = -0.296 R2 = 0.088 Adjusted R2 =

0.080 F = 11.629 Sig. = 0.001 |

||||||

Discussion

The main purpose of the present study was to

investigate the occupational stress and job performance of university library

professionals in North-East India. The results obtained from the current study

revealed that a majority of the university library professionals perceived

occupational stress to a moderate extent. This finding obtained from Table 4 is

in agreement with the result obtained from the study carried out by Mahanta

(2015) and Wijetunge (2012), where the existence of a

moderate level of work-related stress was reported among university library

professionals. However, a few studies carried out by Ogunlana

et al. (2013), Saddiq (2015), and Agyei et al. (2019)

were not in agreement with the prior result and reported a higher level of

work-related stress. The variation in stress levels recorded in the previous

studies may be a result of different organizational factors like conditions of

service, size of the user community served by the library, status of library

staff, financial availability, job security, career growth, and other reasons

that might have brought about different perceptions about work-related stress

among library professionals.

The result obtained from both Tables 5 and 6 reveal

that male and female library professionals do not differ in terms of perceived

occupational stress, which is in line with the studies carried out by Kaur and Kathuria (2018) and Somvir and

Kaushik (2013), wherein there was no significant difference found between male

and female library professionals in terms of occupational stress. In spite of

dual responsibilities at both home and workplace, women library professionals

did not differ from their male counterpart in terms of their perception of

occupational stress. This is contrary to the findings of Ogunlana

et al. (2013), who exposed that male librarians were more susceptible to job

stress than female librarians despite the fact that both were working in the

same environment. The data acquired from Table 7 indicates that significant

mean difference exists between male and female library professionals’

perception of their job performance. Males scored themselves better than

females in the areas of quality of work performance, ability to handle multiple

jobs, communication skills, decision making, problem solving, technical skills,

ability to perform competently under pressure, and contribution to the overall

development of the library (Table 8).

The result presented in Table 9 show a significant

negative relationship between perceived levels of occupational stress and job

performance of library professionals. This finding gives further support to the

literature that demonstrates a significant negative relationship between

occupational stress and job performance, including those studies conducted by

Smith (2000), Kaur and Kathuria (2018), and Nwadiani (2006). This is also in agreement with the claims

of Palmer et al. (2004), which stated that stress beyond an optimal point can

lead to low productivity. Similarly, Hansen (2008) also claimed that stress is

critical to maximizing one’s job performance. Furthermore, McGrath (1976) emphasized that job stress is

considered a factor that may affect organizational effectiveness through lowering employee’s performance. The

stressor intrinsic impoverishment has proved to be the most negative

predictor influencing job performance (Table 10). It implies that the

monotonous nature of library jobs and the lack of ample opportunities to

utilize the abilities and experience of library professionals independently can

also yield negative outcomes on their self-perception of job performance. Other

stressors like under participation, low status, and poor peer relationship were

some of the factors found to negatively affect the job performance of library

professionals in university libraries of North-East India. Furthermore, based

on the findings of Table 11, it was established that occupational stress has a

statistically significant impact on job performance.

Conclusion

Based on the findings from the investigation, it can

be concluded that occupational stress exists among university library

professionals in North-East India, and majority of the professionals

experienced stress up to moderate extent. Though the level of occupational

stress is moderate among library professionals, the study reveals significant

negative relationship between perceived occupational stress and job

performance. It implies that an incremental increase in the level of perceived

occupational stress tends to influence library professionals self-perception of

job performance negatively. Stressors like intrinsic impoverishment, under

participation, low status, and poor peer relationship were some of the factors

negatively influencing their perception of job performance. Male and female

library professionals did not differ with regard to their perceived

occupational stress. On the other hand, males scored themselves better than

females on of eight indicators of job performance: quality of work performance,

ability to handle multiple jobs, communication skills, decision making, problem

solving, technical skills, ability to perform competently under pressure, and

contribution to the overall development of the library. The results reveal a

negative relationship between the two variables of occupational stress and job

performance, but the current study cannot be generalized due to a limited

sample size. Further studies can be conducted with a larger sample size in

order to realize the other organizational or socio-cultural factors that may

have an effect on job performance.

Author

Contributions

Pallabi Devi:

Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology,

Resources, Validation (lead), Visualization, Writing – original draft Prof. Narendra Lahkar:

Conceptualization (lead), Methodology (lead), Project administration,

Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing

References

Agyei, D. D., Aryeetey, F., Obuezie, A. C., & Nkonyeni, S. (2015). The experience

of occupational psychosocial stress among librarians in three African

countries. Library Management, 40(6/7), 368–378. https://doi.org/10.1108/LM-11-2017-0122

Ahmed, A., & Ramzan, M.

(2013). Effects of job stress on employees job performance: A study on banking

sector of Pakistan. IOSR Journal of Business and Management (IOSR-JBM), 11(6),

61–68. https://doi.org/10.9790/487X-1166168

Ajala, E. B. (2011). Work-related

stress among librarians and information professionals in a Nigerian University.

Library Philosophy and Practice (e-journal), 450. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/libphilprac/450

Ali, F., Farooqui, A., Amin,

F., Yahya, K., Idrees, N., Amjad, M., Ikhlaq, M.,

Noreen, S., & Irfan, A. (2011). Effects of stress on job performance. International

Journal of Business & Management Tomorrow, 1(2), 1–7.

Amusa, O. I., Iyoro,

A. O., & Olabisi, A. F. (2013). Work environments and job performance of

librarians in the public universities in South–West Nigeria. International

Journal of Library and Information Science, 5(11), 457–461. https://academicjournals.org/journal/IJLIS/article-abstract/07A6FF242586

Blix, A. G., Cruise, R. J.,

Mitchell, B. M., & Blix, G. G. (1994). Occupational stress among university

teachers. Educational Research, 36(2), 157–169. https://doi.org/10.1080/0013188940360205

Brief, A. P., & Aldag, R. J. (1976). Correlates of role indices. Journal

of Applied Psychology, 61, 468–472.

Carmichael, J.V. (1992). The

male librarian and the feminine image: A survey of stereotype, status, and

gender perceptions. Library and

Information Science Research, 14(4), 411–446.

Chandraiah, K., Agrawal,

S. C., Marimuthu, P., & Manoharan, N. (2003).

Occupational stress and job satisfaction among managers. https://www.ijoem.com/temp/IndianJOccupEnvironMed726-8600177_235321.pdf

Coetzer, W., & Rothmann, S. (2006). Occupational stress of employees in an

insurance company. South African Journal

of Business Management, 37(3),

29–39.

Dina, T. (2016). The effect

of stress on professional librarians’ job performance in Nigerian university

libraries. Library Philosophy and Practice (e-Journal). https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/libphilprac/1431

Graddick, M. M., &

Farr, J. L. (1983). Professionals in scientific disciplines: Sex-related

differences in working life commitments. Journal

of Applied Psychology, 68(4),

641–645.

Greer, B., Stephens, D.,

& Coleman, V. (2001). Cultural diversity and gender role spillover: A working perspective. Journal of Library Administration,

33(1/2), 125–140. https://dx.doi.org/10.1300/J111v33n01_09

Hansen, R.S. (2008).

Managing Job Stress: Ten Strategies for Coping and Thriving. https://www.quint-careers.com

Hinkle, L. E. (1974). The concept of “stress” in the biological

and social sciences. The International Journal of Psychiatry in Medicine,

5(4), 335–357. https://doi.org/10.2190/91DK-NKAD-1XP0-Y4RG

HSE. (2001). Tackling Work Related Stress:

A Managers’ Guide to Improving and Maintaining Employee Health and

Well-being. Health & Safety Executive.

Ilo, P. I., Amusa,

O. I., Chinwendu, N. A., & Esse,

U. C. (2019). Job-related stress and job performance among librarians in

university libraries in Nigeria. Library

Philosophy and Practice (e-journal). https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/libphilprac/3650

Ivancevich, J. M., Matteson,

M. T, & Preston, C. (1982). Occupational stress, Type A behavior,

and physical well-being. Academy of Management Journal, 25, 373–391.

Jena, P. and Pradhan, S.

(2011). Impact of organisational role stress among library professionals of

Odisha: A study. PEARL - A Journal of Library and Information Science, 5(3), 1–8.

Jick T. D. & Mitz L. F. (1985). Sex differences in work stress. Academy of Management Review, 10(3), 408–420. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1985.4278947

Kaur, H., & Kathuria, K. (2018). Occupational stress among library

professionals working in universities of Punjab and Chandigarh. International

Journal of Information Dissemination and Technology, 8(1), 22–24. https://www.ijidt.com/index.php/ijidt/article/view/8.1.5/399

Kaur, H., & Kathuria, K. (2018). Occupational stress and job

performance among university library professionals. Educational Quest: An

International Journal of Education and Applied Social Science, 9(1),

13–17. https://doi.org/10.30954/2230-7311.2018.04.02

Kirkland, J. J. (1997). The

missing women library directors: Deprivation versus mentoring. College and

Research Libraries, 58, 376–84. https://crl.acrl.org/index.php/crl/article/viewFile/15144/16590

BBC News. (2006, January

12). Librarians ‘suffer most stress’. https://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/uk/4605476.stm

Mahanta, K. (2015).

Assessment of stress in university library: A case study. In M. Saikia, M. Eqbal & D. Pratap

(Eds.), Library management: New trends and

challenges (1st ed., pp. 33–41). Academic Publication.

Manshor, A. T.,

Rodrigue, F., & Chong, S. C. (2003). Occupational stress among managers:

Malaysian survey. Journal of Managerial

Psychology, 18(6): 622–628

McGrath, J. E. (1976).

Stress and behavior in organizations. In M. D. Dunnette (Ed.), Handbook of industrial and

organizational psychology (pp. 1351-1395). Rand McNally.

Mosadeghrad, A. M. (2014).

Occupational stress and its consequences. Leadership

in Health Services, 27(3), 224–239. http://tums.ac.ir/1395/02/22/Occupational%20stress%20and%20its%20consequences.pdf-mosadeghrad-2016-05-11-10-24.pdf

Nawe, J. (1995). Work-related

stress among the library and information workforce. Library Review, 44(6),

30–37. https://doi.org/10.1108/00242539510093674

Nunnally, J. C. (1978). Psychometric

theory. McGraw-Hill.

Ofoegbu, F., & Nwadiani, M. (2006). Level of perceived stress among

lectures in Nigerian universities. SA

Journal of Industrial Psychology, 33(1), 66–74. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/292796793_Level_of_perceived_stress_among_lecturers_in_Nigerian_Universities/citations

Ogunlana, E. K., Okunlaya, R. O. A., Ajani, F. O., Okunoye,

T., & Oshinaike, A. O. (2013). Indices of job

stress and job satisfaction among academic librarians in selected federal

universities in South West Nigeria. Annals of Library and Information

Studies (ALIS), 60(3), 212–218. http://op.niscair.res.in/index.php/ALIS/article/view/2204

Ojo, O. (2009). Impact

assessment of corporate culture on employee job performance. Business

Intelligence Journal, 2(2), 389–412. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/26844798_Impact_Assessment_Of_Corporate_Culture_On_Employee_Job_Performance

Oyeniran, K., & Akphorhonor,

B.A. (2019). Assessment of the influence of demographic factors on job

performance of librarians in university libraries in South West, Nigeria. Research Journal of Library and Information

Science, 3(2), 13–19. https://www.sryahwapublications.com/research-journal-of-library-and-information-science/volume-3-issue-2/3.php

Palmer, S., Cooper, C.,

& Thomas, K. (2004). A model of work stress to underpin the Health &

Safety Executive advice for tackling work-related stress and stress risk

assessments. Counselling at Work, Winter, 2-5. https://www.academia.edu/3814856/Palmer_S_Cooper_C_and_Thomas_K_2004_A_model_of_work_stress_to_underpin_the_Health_and_Safety_Executive_advice_for_tackling_work_related_stress_and_stress_risk_assessments_Counselling_at_Work_Winter_2_5)

Pareek, U. (1983). Role stress scales manual. Navin

Publications.

Petek, M. (2018). Stress among

reference library staff in academic and public libraries. Reference Services

Review, 46(1), 128–145. https://doi.org/10.1108/RSR-01-2017-0002

Ratha, B., Hardia,

M., & Naidu, G.H.S. (2012). Occupational stress among library

professionals: A study at Indore City. PEARL - A Journal of Library and

Information Science, 6(1), 1–7. https://www.indianjournals.com/ijor.aspx?target=ijor:pjolis&volume=6&issue=1&article=001

Reena, K.K. (2009). Quality of work life and occupational stress

among the library professionals in Kerala [Doctoral dissertation.

University of Calicut]. Shodhganga. http://shodhganga.inflibnet.ac.in/handle/10603/1415

Saddiq, S., & Iqbal, Z.

(2019). Environmental stressors and their impact at work: The role of job

stress upon general mental health and key organisational outcomes across five

occupational groups. Psychology & Behavioral

Science International Journal, 11(2). https://doi.org/10.19080/PBSIJ.2019.11.555809

Smith, A. (2000). The scale

of perceived occupational stress. Journal

of Occupational Medicine, 50(5),

294–98. https://doi.org/10.1093/occmed/50.5.294

Somvir, S. K. (2013). Occupational

stress among library professionals in Haryana. International Journal of

Knowledge Management & Practices, 1(1), 19–24. http://www.publishingindia.com/ijkmp/57/occupational-stress-among-library-professionals-in-haryana/210/1588/

Srivastava, A. K., &

Singh, A. P. (1984). Manual of

Occupational Stress Index. Manovaigyanik Parikchhan Sansthan.

Wiebe, T.J. (2004). Issues

faced by male librarians: Stereotypes, perceptions, and career ramifications. Colorado Libraries, 31(1), 11–13.

Wijetunge, P. (2012).

Work-related stress among the university librarians of Sri Lanka. Journal of the University Librarians Association,

Sri Lanka, 16(2), 125–137. https://doi.org/10.4038/jula.v16i2.5204