Research Article

Beyond Reference Data: A Qualitative Analysis of Nursing

Library Chats to Improve Research Health Science Services

Samantha Harlow

Online Learning Librarian

University of North Carolina

Greensboro

Greensboro, North Carolina,

United States of America

Email: slharlow@uncg.edu

Received: 25 Aug. 2020 Accepted: 24 Jan. 2021

![]() 2021 Harlow. This is an Open Access article

distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

2021 Harlow. This is an Open Access article

distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

DOI: 10.18438/eblip29828

Abstract

Objective - The objective of

this study was to analyze trends in academic library reference chat transcripts

with nursing themes, in order to improve all library services and resources

based on the findings.

Methods - In Fall 2018,

health science liaison librarians performed a qualitative study by analyzing 60

nursing chat transcripts from LibraryH3lp. These chats were tagged, anonymized,

coded, and then analyzed in Atlas TI to identify patterns and trends.

Results - Chat analysis

showed that librarians staffing chat are meeting the research needs of nursing

patrons by helping them find full-text articles and suggesting the appropriate

library databases. In order to further improve these virtual services,

workshops were offered to Library and Information Science (LIS) interns and

staff who answer reference chats. Nursing online tutorials and research guides

were also improved based on the results.

Conclusion - This study

will help academic libraries improve and expand services into the virtual

realm, to support library employees and patrons during the COVID-19 pandemic

and beyond. Virtual reference chat is not going away; in the current academic

environment it is needed more than ever. Using these library chats as the basis

for additional chat staff training can reduce staff anxiety and prepare them to

better serve patrons.

Introduction

The University of North Carolina Greensboro (UNCG), a

mid-sized public research university, has a nursing program with a strong

online presence to accommodate the department’s large population of

non-traditional students. Non-traditional students are defined as students who

fall into any one of the following groups: over 24 years of age; entry to

college delayed by at least one year following high school; single parents;

employed full-time; attending a postsecondary institution part-time; with

dependents; financially independent; or not possessing a high school diploma

(Choy, 2002). According to the Association of College & Research Libraries

(ACRL) Standards for Distance Learning Library Services, academic libraries

should provide equitable resources and services for all of their students,

including those who learn and study online (2016). In order to meet the needs

of all campus researchers and learners, the UNCG University Libraries provide a

variety of information literacy services and instruction through the Research,

Outreach, and Instruction (ROI) department, which houses academic librarian

liaisons. Through the ROI department, liaisons and staff run a very popular

virtual chat service, that receives thousands of chats a year. This department

also helps students by providing many other virtual and face-to-face services,

including: information literacy and research instruction; one-on-one

consultations with students and faculty; research guides through Springshare

LibGuides platform; and a variety of Canvas (learning management system)

integrations, including a LibGuides LTI (learning tools interoperability).

Increasing numbers of nursing programs are moving online,

and according to the “Guide to Online Schools: Accredited Online Nursing Programs

by State” website (2019), there are at least 380 online nursing schools in the

US. UNCG offers many nursing degrees and certificates, and the Master's of Science (MS) and Post-Baccalaureate Certificate

(PBC) in Nursing Administration and Nursing Education are offered fully online (University

of North Carolina Greensboro, 2020). UNCG has also identified health education

as a focus area for the general student body, with “Health and Wellness” as a

theme of the Strategic Plan; this plan characterizes health and wellness as

“broadly defined to encompass the many dimensions necessary for individuals to

cope, adapt, grow, and develop” (University of North Carolina Greensboro, 2013).

Nursing students are a strong online and non-traditional population, and with

health and wellness as target areas for campus learning, it is more important

than ever to provide effective and equitable health science library reference

services to students. Within the Libraries, the health science liaison works

with a variety of academic health science departments including Nursing, while

the online learning librarian is liaison to Community and Therapeutic

Recreation, Kinesiology, and Public Health Education. Liaisons provide a

variety of services to their departments, and since Nursing has always had a

strong online presence, the health science librarian offers virtual research

consultations, webcasts on a variety of research topics, and online

orientations for students.

Based on this important student population, the growth of

online learning and non-traditional students, and the popularity of the

reference chat library service, these two health science liaison librarians

performed a qualitative reference analysis on reference chat transcripts from

nursing students and instructors. This study was performed in an effort to

improve service offerings in several areas, but particularly chat services to

nursing students; improving research services to nursing students also helps a

variety of other patrons, including other health science departments and all

students studying online. This study sought to answer the following research

questions: what trends do we see in library chats based on nursing themes,

rather than numbers and usage counts? What patterns exist in nursing chats within

the library? How can we improve library services and resources based on nursing

chat trends?

Literature Review

A virtual chat service is a vital synchronous online

service for library patrons (both face-to-face and distance populations), and

there are many studies on providing reference services to researchers through

chat. Some studies survey academic librarians about their chat reference

services and how they train staff to answer chats (Devine, Paladino, &

Davis, 2011), while others explore the usefulness of having full-time

librarians provide service through chat reference systems (Maloney & Kemp,

2015). Many chat analysis projects take a large-scale qualitative approach by

analyzing datasets of academic chat transcripts to show overall improvements over

time (Baumgart et al., 2016; Brown, 2017; Dempsey, 2019). Mungin

(2017) at James Madison University analyzed chat transcripts in Dedoose over a five-year span in order to improve chat

reference; and as recently as 2019, at Utah State University (which has a high

population of students studying online), a group of librarians and learning

technologists looked at chat trends over a year by analyzing 1600 chat

transcripts through coding. Based on the findings of this analysis, the group

made training resources and best practice handouts for answering chats (Eastman

et al., 2019). In another chat analysis project, Logan, Barrett, and Pagotto (2019) used coding to analyze almost 500 chat

transcripts to find behaviors to avoid. With growing student populations and

online services and resources, many libraries must rely more heavily on

non-librarians and student workers staffing virtual reference systems. Barrett

and Greenberg (2018) conducted a study proving the value of student workers by

performing exit interviews with patrons served. In order to help librarians and

their non-librarian colleagues better reach distant students, offering

professional development through online research guide or courses within the

university learning management system is therefore helpful (Bliquez

& Deeken, 2016).

Understanding the information and digital literacy needs

of nursing undergraduate and graduate students can help improve library

reference services for all students, regardless of whether they are studying

online or face-to-face. Librarians have long understood the need for virtual

reference services for nursing students. Guillot and Stahr

(2004) studied the efficiency of a virtual reference desk for nursing patrons

at their university and found that distance nursing students valued the online

research support system. Many qualitative studies have been performed on the

research needs of nursing students. Interviewing nursing students who may be

studying online can help librarians understand the unique life experiences of these

students and their information and digital literacy skills (Craig & Corrall, 2007; Duncan & Holtslander,

2012; Ledwell et al., 2006; Reeves & Fogg, 2006;

Stein & Reeder, 2009). Surveys are another method of understanding the

information seeking needs of nursing students; for example, Al-Gamal and

colleagues’ (2018) surveyed nursing students about stress and the coping

strategies they used during their clinical rotations.

The increasing shift toward online nursing education

means that it is more vital than ever to provide a variety of asynchronous

virtual research training for nursing students who prefer this method of help

over synchronous chats; research guides such as Springshare LibGuides and

online tutorials can help accommodate nursing students on their own time.

Nursing research guides can serve as portals for accessing virtual and physical

collections (Johnson & Johnson, 2017). Stankus

and Parker (2012) performed a study on nursing LibGuides across the US from a

variety of libraries and found the information on the guides diverse and

varied; there were some commonalities, such as inclusion of major medical

databases and resources like EBSCO’s CINAHL, as well as PubMed/MEDLINE, and a

focus on evidence based practice to inform research. LibGuides can house online

tutorials on a variety of information literacy health science topics. Online

tutorials can include various multimedia such as videos, PDFs, presentations,

and more, and can be created by faculty, instructional designers, or

librarians. Online tutorials are time consuming to create, but they are

powerful tools for asynchronous educational opportunities for nursing students

studying online. Nurses and librarians have demonstrated in a variety of

studies that using online tutorials in a flipped classroom approach or through

an online guide is valuable (Gilboy et al., 2015; Schlairet et al., 2014; Schroeder, 2010). Lastly, creating

online synchronous courses or professional development opportunities can better

reach many nursing students (Smith & O’Hagan, 2014).

Librarians have consistently provided information

literacy and reference consultations, instruction, and assessment to nursing

students, ideally while also integrating the important competency of evidence

based practice (EBP) (Adams, 2014). Librarians are adapting to the demographics

of nursing programs and adjusting services for an increasingly online

population. When nursing researchers are surveyed or interviewed about their

information literacy and evidence based practice essentials, there is a call

for more digital support and expanding research services to include

grant-writing, scholarly communication, and data management (Nierenberg, 2017; Wahoush & Banfield, 2014). Though more and more online

library services and tutorials are being offered to nursing students, some of

these students are not digital natives and may not possess all of the computer

literacy skills needed for researching online (Turnbull, Royal, & Purnell,

2011; Brettle & Raynor, 2013). Virtual chat,

library services, and asynchronous information literacy instruction are widely

discussed in the literature, but no previous studies combine the research needs

of nursing students with an in-depth chat analysis of this population. This

study seeks to analyze nursing reference chats to help academic librarians

better serve all patrons.

Methods

The LibraryH3lp system is used to provide virtual chat

reference to UNCG library patrons. This chat service is available to non-UNCG

patrons as well, but this study only analyzes transcripts of internal patrons.

This chat service is staffed mostly by personnel in the ROI department, along

with some librarians and staff from the Music Library and the Special

Collections and University Archives (SCUA) department. These chats are also answered

by UNCG Library and Information Studies (LIS) graduate student interns working

in the ROI department. During a typical semester, chat service is online and

active from 8:00am until 11:45pm Monday through Thursday, and during the day

and into the early evening on Friday through Sunday. LibraryH3lp is heavily

used, receiving around 3500 chats a year.

In Fall 2018, the two health science liaison librarians

downloaded all full chat transcripts from the months August, September, and

November 2016, with a total of 1416 chat transcripts. This time frame was

selected to avoid singling out any current librarians, staff, or students

taking chats because these months provided a sampling of the busiest Fall

semester months. To find these transcripts, a CSV file was created from the

backend of LibraryH3lp of all chat transactions from Fall 2016, and then edited

based on the selected months. The CSV file was converted into a XLS file to

perform a “control find” of nursing keywords to identify relevant chats. These

keywords were developed by the health science librarian, who is the nursing

department liaison, based on instruction sessions and common research services,

questions, or issues that arise within the nursing department. The keywords

used to identify the chats were: Nur*, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied

Health Literature (CINAHL); PubMed; Lea (first name of the health science

librarian); Evidence Based Practice (EBP); systematic reviews; integrative;

health; hospital; patient; clinical; anesthesia; Doctor of Nursing Practice

(DNP); Bachelor of Science in Nursing (BSN); Master’s

of Science in Nursing (MSN); practitioner; geriatric; and patient, population,

problem, intervention, comparison, and outcome (PICO).

Based on this keyword and search method, 60 chat

transcripts were identified and pulled from the original 1416 transcripts into

Box (UNCG’s most secure cloud storage system) using the Note platform. Putting

the transcripts within Box Note allowed each transcript to also have relevant

metadata attached, such as date, length of time the patron waited before staff

were able to engage with the chat, source of the chat, length of the chat,

category of chat (Reference, Service, Technology, Library Directions, or

Services), description of chat, and READ (reference effort assessment data)

scale rating. READ scale is a measurement of the difficulty level of the

reference transaction of the chat (Karr Gerlich,

n.d.). Another reason the transcripts were placed in Box Notes was to redact

any identifying information related to students or instructors, such as names,

email addresses, or phone numbers. From the chat data, a master spreadsheet was

created in Google Sheets, allowing librarians to see the overall trends of

length of chat, time of chat, READ scale, and more.

Once the transcripts were anonymized within Box Notes,

one PDF of the selected transcripts was created and read by both librarians.

These librarians then created groups of themes and corresponding codes to

determine an overall and consistent list to be applied to the transcripts. Both

librarians coded the chat transcripts based on the following groups:

Information Need, Reference Interviewing, Recommendations, Patron Emotions, and

Challenges and Barriers. See Table 1 for a full list of codes used for this

analysis, organized by groups.

Both librarians attended assessment workshops on coding qualitative

research in Atlas TI by UNCG OAERS (Office of Assessment and Evaluation

Research Services). The research design for this study was informed by Creswell

and Poth’s (2017) guide, which suggests five traditional qualitative research

approaches: narrative research, phenomenology, grounded theory, ethnography,

and case study. This study used the narrative research approach, considering

the virtual chats the narrative to be analyzed. When the codes were finalized,

they were input and applied to transcripts using Atlas TI. The librarians

initially applied the codes on separate sets of transcripts, and then switched

transcript sets to ensure that each chat was examined by both parties. To

minimize bias and errors when the transcripts were switched, each party checked

the other’s codes for consistency and gaps. From Atlas TI, the code group could

be used to analyze chats based on the individual codes. All forms of

qualitative research are subjective and results can shift depending on the

individual reading and coding of each transcript. Though there were two coders

on each transcript, themes could be missed based on the length of chat or state

of the reader.

Results

Information Need

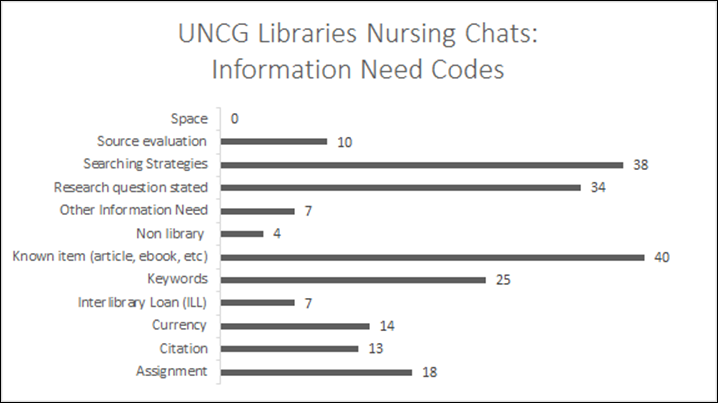

The first code group to be analyzed was “Information

Need”, in order to establish trends of research of nursing library patrons.

When looking at the coding group of “Information Need”, the most common themes

were students and instructors looking for the full-text of a known item, such

as an article or e-book, and searching strategies for research assignments (Figure

1). Patrons stating their research question, keywords, and assignments were

also heavily coded. The code of “Space” got no mentions in this set of nursing

chats.

Table

1

Code

Groups and Codes for Fall 2016 UNCG Libraries Virtual Chat Nursing Transcripts

Analysis, Inputted into Atlas TI

|

Code

Group: |

Codes

within Group: |

|

Information

Need |

Keywords,

searching strategies, hours, space, assignment, research question stated,

course mentioned, student type DNP, student type BSN, student type Masters,

Student Type RN/BSN, student type Doctoral, student type DNP Anesthesia,

resource type peer review, resource type integrative review, resource type

systematic review, resource type research article, resource type evidence

based, resource type theoretical article, resource type law or court cases,

citation, known item journal, known item article, known item database, known

item e-book, known item other, currency, source evaluation, non-library

resource writing center, non-library resource tutoring, non-library resource

technology assistance, non-library resource community partners, other

information need |

|

Reference

Interviewing |

Request

for clarification of research need, ask for course number, navigation of

resource, ask if more assistance needed, confirmation need was met,

transferred chat, other reference interviewing |

|

Recommendations |

Database

CINAHL, database PubMed, database Dynamed Plus,

database Healthy People 2020, database Cochrane, database Scopus, database

PsycINFO, database Academic Search Complete, database ProQuest, database

other, journal A-Z list, assistance library catalogue, referral liaison,

referral instructor, filters in catalogue or database, interlibrary loan

(ILL), citation management Zotero, citation management EndNote, library

tutorials PATH, library tutorials other, course guide, subject guide,

physically come into the library, other recommendation |

|

Patron

Emotions |

Frustration,

gratitude, stress and anxiety, uncertainty, other patron emotions |

|

Challenges

and Barriers |

Full-text,

service not working, resource not working, access off campus, access through

browser, access database, access catalogue, access e-book, access textbook,

permalinks, interdisciplinary research need, misunderstandings assignment,

misunderstandings other, business librarian, business of patron, patron

disappears, technical issue, too many results, too few results, usability

website, usability chat, other challenges and barriers |

Figure

1

Chart

depicting the amount of times “Information Need” was coded, meaning the need of

the patron chatting for research help.

Patron Emotion

Findings within the “Patron Emotion” code group show that

people answering chats are doing an effective job of providing permalinks,

offering descriptions of navigating to resources, creating keywords, boosting

students’ academic confidence, and helping them learn more about the research

process. The “Gratitude” code was often found within the transcripts. Many

chats ended with nursing patrons saying “Thank you so much! This was so

helpful!”, particularly when learning about how to narrow down search results,

how to use allied health and nursing library resources, and how to use library

databases more efficiently. In many chats nursing students could immediately

use the research skills showcased in the chat in their

research. For example, one chat patron stated: “I'll try to limit [my search

results] down with keywords, but that database has better results!”

The most coded emotion from patrons was “Gratitude”, but

the second most coded was “Uncertainty”, followed by “Frustration”. Sometimes

patrons were unsure of their needs since they were new to the research process.

For example, it was not uncommon for nursing patrons to write in messages like,

“Hey. Never done this before but I'm having some difficulty finding articles on

my topic and I know there are articles out there. I am just not finding them.

Can you help?” Many times, the chat nursing patrons note being busy working, as

well as being a student, so not having time to properly research their

assignment. In some cases, the patrons were at work while chatting with

librarians, such as in this scenario where the patron writes “currently at work

and tried using the library online already and having trouble which is why I

want to physically go in.”

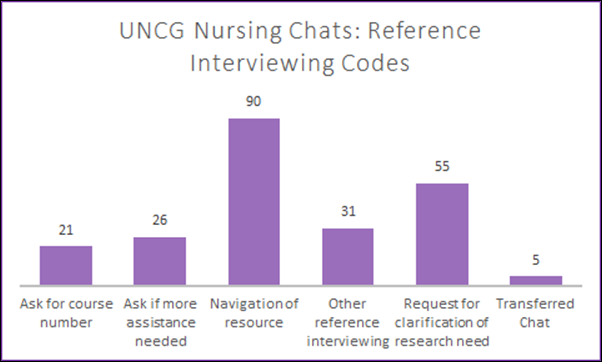

Figure

2

Chart

of UNCG Libraries nursing chats showing the “Reference Interviewing Codes”,

showing the interactions of the librarian answering the chat questions.

Reference Interviewing

Reference interactions of the people answering the chats

were also coded (Figure 2). Librarians, students, and staff answering reference

chats consistently provided navigation to resources and requested clarification

of research needs. There were fewer instances of those staffing chat asking

students for the course number for their specific nursing course (only 35% of

chats requested a course number). A small number of nursing chats were also

transferred to other people staffing chat based on their expertise or

availability.

Challenges and Barriers

The most common challenges and barriers of the chats were

also coded. “Full-text” was the most common challenge touched upon, but

“Busyness of Librarians” and “Busyness of Patron” also received many mentions

in these chats. For example, librarians would pause and write, “Sorry for the

delay, I had a patron at the desk while you were chatting.” Patrons sometimes mentioned

challenges with “Access off Campus” and “Technical Issues” with library

resources. More patrons had issues with “Too Many Results” when searching for

resources than “Not Enough Results.” The overall code group of “Challenges and

Barriers” was the least coded theme.

Recommendations

The specific recommendations from people staffing chat

were also coded. Databases were the most commonly advocated resource for

patrons to use to search for research materials (in almost 77% of the chats

analyzed), with CINAHL recommended the most often. The next most frequently

mentioned research technique was for patrons to use filters to narrow down

searching in databases or the library catalogue. Staff and librarians also

encouraged the use of course and subject guides on nursing topics, and in a

little over 18% of the chats, a one-on-on meeting with the liaison librarian

was endorsed. Searching in the library journal finder or a specific nursing

journal was never mentioned or promoted in these chats.

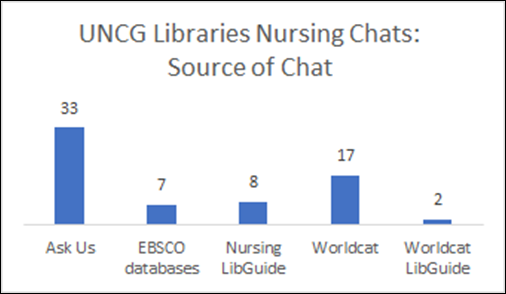

Figure

3

UNCG

Libraries nursing chat chart depicting the source of the chat.

General Trends

The coding groups provided significant insight into

nursing research needs. Additionally, the overall trends of the nursing chats

are useful for improving chat services. The master spreadsheet of nursing chats

includes chat source, time of chat, length of chat, whether the chat was

transferred, type of patron and course (if mentioned), READ Scale, and

description of the chat. The chats were received evenly throughout the day,

with the afternoon being the slightly more popular time for patrons to chat

(43%). Most chats came in from the Libraries Ask Us homepage, where the chat

box is embedded within the Libraries home website (Figure 3). The second most

popular source of chats was OCLC WorldCat (the library catalogue) and the third

was the nursing subject guide. Chats that included mentions of a specific

course were tagged; this illustrated that 57% of students did not mention a

course when chatting in with a research need. People staffing chat can choose

to rate the difficulty level of each chat using the READ Scale. With the chats

we analyzed, many did not have READ scale ratings; of those that did get a

rating, the most common rating was 3. At UNCG Libraries, READ Scale 3 means

reference interactions such as finding books or DVDs in the catalogue by title or

author (i.e., “I need to find Toni Morrison’s Beloved”); accessing research

guides; accessing subject databases; and basic citation style questions that

can be answered using online citation style guides.

Discussion

Evaluating Nursing Chat Transcripts

Reference themes proved valuable in the coding analysis.

“Busyness of Librarians” and “Busyness of Nursing Students” were commonly

coded; this shows the importance of offering a variety of virtual reference

services, such as online learning objects, chat, and virtual consultations.

Within the “Recommendation” coding groups, not many library staff asked for a

course number from chat patrons. While this could mean that a reference need

was as simple as asking for a PDF of an article or that the chat staff was

pressed for time, clarifying if there is a course number or assignment involved

enables staff to better market course-specific research guides with relevant

tutorials, links to databases, and applicable contact information. Librarians

staffing chat should consistently offer detailed resource navigation

instructions, as well as follow up information directing patrons to the nursing

research guide and librarian. This is a particularly useful approach at a

university where health science is in the general education curriculum and is

part of the strategic plan, enabling library chat staff to quickly and

confidently fulfil the research need and move on to handle the next reference

interaction. Since librarians working chat are often multi-tasking by handling

more than one chat or by talking to patrons at the physical reference desk, it

is vital for a library department to also create training to boost confidence

with answering nursing research questions.

A frequently coded topic was the need for help with

identifying keywords for searching in databases, which confirms the high

prevalence of patrons searching for “known items.” Highlighting the value of

using library nursing and allied health databases and the catalogue is always

integral during library information literacy instruction; this data shows the

need to better showcase the differences between library resources and tools

like Google Scholar (paywalls, lack of evaluation of quality of journals,

insufficient search filters) within nursing and library online learning

objects, instruction, consultations, webcasts, and orientations.

When helping patrons look for research articles, the

health database CINAHL was usually recommended. Though CINAHL is a great

solution for finding health science and nursing articles, there are many other

databases that can direct patrons to research resources, including PubMed which

has different search functionality. Throughout the transcripts, patrons

consistently mentioned using PubMed. For example, a patron wrote “I'm looking for

a full text scientific article through the journal: Current Medicinal Chemistry.

What's the best way to get a full text? I have links to the PubMed and NCBI

page but can’t find the PDF of the article.” Librarians staffing chat need to

be able to quickly navigate between different types of databases to better

serve nursing patrons.

Training on Nursing Research

This chat coding project shows that nursing patrons need

assistance finding full-text clinical studies and articles, while also

understanding the different nursing and allied health library databases. When

informally surveying library staff about nursing chat training needs, one

library staff chat member stated the desire for training on “more information

about PubMed. I often recommend CINAHL because it's what I know the most. I've

used PubMed in the past and know the overall gist, but some more details about

advanced searching, how the database works, would be great.” Based on this chat

analysis and the needs of librarians working chat, follow up training sessions

were created and administered by the health science librarians.

The trainings created were presented to the UNCG Library

and Information Science (LIS) interns, with other chat staff and liaison

librarians invited to participate. These training sessions about health science

research and resources have now been offered every academic year since 2018,

for a total of three workshops. Topics covered include recognizing research

articles in the context of health sciences (primary research and types of

research studies), evidence based practice, PICO, health science databases

PubMed and CINAHL, and chat practice. The workshop generally ends with chat

exercises from transcripts pulled from this study, and the attendees answer

them on Google Forms or Google Docs within a Think, Pair, Share or group

discussion format. When these workshops were assessed, LIS interns reported

that these nursing chat and research workshops were helpful in reducing their

anxiety about answering health science reference questions.

Reviewing Nursing Online Learning Objects

This study created an opportunity for immediate action

for chat staff training, which was planned and performed. It also prompted

review of the nursing research guides, so that busy nursing patrons and chat

staff can more quickly find relevant information and resources. Since this

study, the Libraries ROI department has also revamped their suite of

information literacy research tutorials.

This in-depth study of the needs of nursing patrons

therefore helps to inform the need for more health science-related online

learning objects and tutorials, as well as more online support on general topics

such as finding full-text, locating permalinks, navigating the library website,

and using the library catalogue and databases. Since this study, many nursing

research online learning objects have been added to help train librarians,

faculty, and students on concepts such as advanced searching in CINAHL, PubMed

basics, the new PubMed interface, evaluating health sources online, and

predatory journals.

Future Directions

Qualitative research studies involve limitations,

including differing interpretations and errors that can happen with a large

amount of data which takes a long time to code and analyze. The methodology of

this study was challenging because of its time-consuming nature, but it was

useful as an in-depth examination of the reference needs of a specific patron

population. A similar study could be designed looking at different academic

subjects or themes that feature in the Libraries’ general chat interactions,

such as e-books, interlibrary loans, and streaming. A variation on this study

would be to apply the same methodology to recordings of nursing student

consultations. Another continuation of this study would be to survey the patron

population alongside a chat analysis. Since this study was performed, the

online learning librarian at UNCG has interviewed students studying online

about their overall information retrieval and research needs. A similar

approach could be taken with nursing students based on this study, to further

identify their specific and diverse research needs. Another future study could

encompass pretesting and posttesting to gauge whether

nursing students’ research knowledge improves via long reference chat sessions.

Starting in March 2020, due to the COVID-19 pandemic many

of the library personnel who staff the chat service are working from home.

Additionally, LIS interns no longer staffed the chat in Summer 2020. Based on

this shift in the academic workflow, there have been several virtual

professional development workshops. The nursing librarian performed multiple

sessions on finding trustworthy health information online during COVID-19. This

virtual workshop model could be adapted based on assessment from current

programming to help LIS interns and librarians staffing chat.

Conclusion

Though time-intensive, this study on library chat

transcripts shows the diversity of needs of nursing patrons, which included a

large population of non-traditional and distance students. An in-depth

examination of nursing chats led to a series of workshops and trainings for

library chat staff and LIS students on nursing research, while also helping

library personnel develop more tutorials and online learning objects on health

information literacy. Improving the vital online service of chats through

training on nursing research, evidence based practice, PICO, and specific

health databases creates a better research environment for all patrons and

librarians. This study will continue to help the libraries improve and expand

workshops into the virtual realm, supporting library employees and patrons

during the COVID-19 pandemic. Virtual reference chat is not going away; in the

current academic environment it is needed more than ever. Studying library

chats beyond basic use statistics may reduce library chat staff anxiety and

prepare them to better serve patrons.

References

Adams,

N. E. (2014). A comparison of evidence-based practice and the ACRL Information

Literacy Standards: implications for information literacy practice. College & Research Libraries, 75(2), 232–248. https://doi.org/10.5860/crl12-417

Al‐Gamal,

E., Alhosain, A., & Alsunaye,

K. (2018). Stress and coping strategies among Saudi nursing students during

clinical education. Perspectives in

Psychiatric Care, 54(2), 198–205.

https://doi.org/10.1111/ppc.12223

Association

of College & Research Libraries. (2016). Standards for distance learning

library services. In ALA American Library

Association. Retrieved 20 September 2020 from http://www.ala.org/acrl/standards/guidelinesdistancelearning

Barrett,

K., & Greenberg, A. (2018). Student-staffed virtual reference services: How

to meet the training challenge. Journal

of Library & Information Services in Distance Learning, 12(3–4), 101–119. https://doi.org/10.1080/1533290X.2018.1498620

Baumgart,

S., Carrillo, E., & Schmidli, L. (2016).

Iterative chat transcript analysis: Making meaning from existing data. Evidence Based Library and Information

Practice, 11(2), 39–55. https://doi.org/10.18438/B8X63B

Bliquez, R., & Deeken, L. (2016). Hook, line and canvas: Launching a

professional development program to help librarians navigate the still and

stormy waters of online teaching and learning. Journal of Library & Information Services in Distance Learning,

10(3–4), 101–117. https://doi.org/10.1080/1533290X.2016.1206778

Brettle, A., &

Raynor, M. (2013). Developing information literacy skills in pre-registration

nurses: An experimental study of teaching methods. Nurse Education Today, 33(2),

103–109. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2011.12.003

Brown,

R. (2017). Lifting the veil: Analyzing collaborative virtual reference

transcripts to demonstrate value and make recommendations for practice. Reference and User Services Quarterly, 57(1), 42–47. https://doi.org/10.5860/rusq.57.1.6441

Choy,

S. (2002). Nontraditional undergraduates, National

Center for Education Statistics. In Findings

from the Condition of Education. Retrieved 20 September 2020 from https://nces.ed.gov/pubs2002/2002012.pdf

Craig,

A., & Corrall, S. (2007). Making a difference?

Measuring the impact of an information literacy programme for pre-registration

nursing students in the UK. Health

Information & Libraries Journal, 24(2),

118–127. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-1842.2007.00688.x

Creswell,

J. W., & Poth, C. N. (2017). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches

(4th edition). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, INC.

Dempsey,

P. R. (2019). Chat reference referral strategies: Making a connection, or

dropping the ball? College & Research

Libraries, 80(5), 674–689. https://doi.org/10.5860/crl.80.5.674

Duncan,

V., & Holtslander, L. (2012). Utilizing grounded

theory to explore the information-seeking behavior of senior nursing students. Journal of the Medical Library Association,

100(1), 20–27. https://doi.org/10.3163/1536-5050.100.1.005

Eastman,

T., Hyde, M., Strand, K., & Wishkoski, R. (2019).

Chatting without borders: Assessment as the first step in cultivating an

accessible chat reference service. Journal

of Library & Information Services in Distance Learning, 13(3), 262–282. https://doi.org/10.1080/1533290X.2019.1577784

Gilboy, M. B., Heinerichs, S., & Pazzaglia,

G. (2015). Enhancing student engagement using the flipped classroom. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior,

47(1), 109–114. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jneb.2014.08.008

Guillot,

L., & Stahr, B. (2004). A tale of two campuses:

Providing virtual reference to distance nursing students. Journal of Library Administration, 41(1–2), 139–152. https://doi.org/10.1300/J111v41n01_11

Johnson,

C. V., & Johnson, S. Y. (2017). An analysis of physician assistant LibGuides: A tool for collection development. Medical Reference Services Quarterly, 36(4), 323–333. https://doi.org/10.1080/02763869.2017.1369241

Karr

Gerlich, B. (n.d.). Welcome to the READ Scale research web site. Retrieved

from http://www.readscale.org/

Ledwell, E. A., Andrusyszyn, M. A., & Iwasiw,

C. L. (2006). Nursing students’ empowerment in distance education: Testing

Kanter’s Theory. Journal of Distance

Education, 21(2), 78–95.

Retrieved from https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ807804

Logan,

J., Barrett, K., & Pagotto, S. (2019).

Dissatisfaction in chat reference users: A transcript analysis study. College & Research Libraries, 80(7), 925–944. https://doi.org/10.5860/crl.80.7.925

Maloney,

K., & Kemp, J. H. (2015). Changes in reference question complexity

following the implementation of a proactive chat system: Implications for

practice. College & Research

Libraries, 76(7), 959–974. https://doi.org/10.5860/crl.76.7.959

Mungin, M. (2017).

Stats don’t tell the whole story: Using qualitative data analysis of chat

reference transcripts to assess and improve services. Journal of Library & Information Services in Distance Learning,

11(1–2), 25–36. https://doi.org/10.1080/1533290X.2016.1223965

Reeves,

J. S., & Fogg, C. (2006). Perceptions of graduating nursing students

regarding life experiences that promote culturally competent care. Journal of Transcultural Nursing, 17(2), 171–178. https://doi.org/10.1177/1043659605285410

Schlairet, M. C., Green,

R., & Benton, M. J. (2014). The flipped classroom: Strategies for an

undergraduate nursing course. Nurse

Educator, 39(6), 321–325. https://doi.org/10.1097/NNE.0000000000000096

Schroeder,

H. (2010). Creating library tutorials for nursing students. Medical Reference Services Quarterly, 29(2), 109–120. https://doi.org/10.1080/02763861003723135

Smith,

S. C., & O’Hagan, E. C. (2014). Taking library instruction into the online

environment: One health sciences library’s experience. Journal of the Medical Library Association, 102(3), 196–200. https://doi.org/10.3163/1536-5050.102.3.010

Stankus, T., &

Parker, M. A. (2012). The anatomy of nursing LibGuides.

Science & Technology Libraries, 31(2), 242–255. https://doi.org/10.1080/0194262X.2012.678222

Stein,

J. V., & Reeder, F. (2009). Laughing at myself: Beginning nursing students’

insight for a professional career. Nursing

Forum, 44(4), 265–276. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6198.2009.00152.x

University

of North Carolina Greensboro (2013). The University of North Carolina at Greensboro

strategic plan core elements: Taking giant steps. In UNC Greensboro. Retrieved 20 September 2020 from https://strategicplan.uncg.edu/core-elements/

University

of North Carolina Greensboro (2020). Graduate degrees. In UNCG Online. Retrieved 20 September 2020 from https://online.uncg.edu/graduate-programs/

Wahoush, O., &

Banfield, L. (2014). Information literacy during entry to practice:

Information- seeking behaviors in student nurses and recent nurse graduates. Nurse Education Today, 34(2), 208–213. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2013.04.009