Research Article

Information Seeking Anxiety and Preferred Information

Sources of First-Generation College Students

Stacy Brinkman

Head of Education and Outreach

University of California,

Irvine

Irvine, California, United

States of America

Email: brinkmas@uci.edu

Josefine Smith

Assistant Professor,

Instruction and Assessment Librarian

Shippensburg University

Shippensburg, Pennsylvania,

United States of America

Email: jmsmith@ship.edu

Received: 4 Sept. 2020 Accepted: 3 Jan. 2021

![]() 2021 Brinkman and Smith. This

is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

2021 Brinkman and Smith. This

is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

DOI: 10.18438/eblip29843

Abstract

Objective – To determine

whether information seeking anxieties and preferred information sources differ

between first-generation college students and their continuing-generation

peers.

Methods – An online survey

was disseminated at two public college campuses. A total of 490 respondents

were included in the results. Independent variables included institution, year

in college, and generational status. Instead of using a binary variable, this

study used three groups for the independent variable of generational status,

with two first-generation groups and one continuing-generation group based on

parental experience with college. Dependent variables included 4 measures of

information seeking anxiety and 22 measures of preferred information sources.

Responses were analyzed using SPSS. One-way independent ANOVA tests were used

to compare groups by generational status, and two- and three-way factorial

ANOVA tests were conducted to explore interaction effects of generational

status with institution and year in college.

Results – No significant

differences in overall information seeking anxiety were found between students

whose parents had differing levels of experience with college. However, when

exploring the specific variable of experiencing anxiety about “navigating the

system in college,” a two-way interaction involving generational status and

year in school was found, with first-generation students with the least direct

experience with college reporting higher levels of anxiety at different years

in college than their peers. Two categories of first-generation students were

found to consult with their parents far less than continuing-generation peers.

The study also found that institutional or generational differences may also

influence whether students ask for information from their peers, librarians,

tutoring centers, professors, or advisors.

Conclusion – This study

is one of the first to directly compare the information seeking preferences and

anxieties of first-generation and continuing-generation students using a

non-binary approach. While previous research suggests that first-generation

students experience heightened anxiety about information seeking, this study

found no significant overall differences between students based on their

generational status. The study reinforced previous research about

first-generation college students relying less on their parents than their

continuing-generation peers. However, this study complicates previous research

about first-generation students and their utilization of peers, librarians,

tutoring centers, professors, or advisors as information sources, and suggests

that institutional context plays an important role in shaping first-generation

information seeking.

Introduction

In

the past three decades, the number of individuals attending higher education

for a bachelor’s degree has increased: according to the Current Population

Survey, 33.4% of adults over 25 in 2016 held a bachelor’s degree, a figure that

has increased from 4.6% in 1940 (U.S. Census Bureau, 2017). One group that has

been receiving increasing attention is first-generation (FG) college students,

a population that accounts for up to 56% of undergraduates, depending on the

parameters used to define this group (Center for First-Generation Student

Success, 2019). While a large body of literature exists on characteristics of

FG students, less is known about FG students’ information seeking behavior,

particularly in comparison to non-FG students.

The current paper builds on previous

research that explored FG students’ information seeking strategies, as well as

their self-perceptions of their information seeking abilities (Brinkman et al.,

2013). Brinkman et al. found relationships between affective concerns of information

seeking anxiety and academic information seeking behaviors in FG students, but

did not compare FG students to non-FG students. Our study adds to the existing

literature by exploring levels of information seeking anxiety as well as

information source preferences and comparing responses from categories of FG

and non-FG students, and also samples students from two institutions.

Literature

Review

Historically, researchers studying FG

students emphasize the “challenges” that this population faces (Ilett, 2019). Surveys conducted by the

National Center for Educational Statistics indicated that FG students were more

likely to come from lower socioeconomic backgrounds, were ethnic minorities,

had taken fewer college-preparatory classes (Choy, 2001), or were more likely

to have children and work full-time while enrolled (Nunez & Cuccaro-Alamin, 1998). In early foundational studies, researchers

discussed several challenges faced by FG students in higher education: lower

levels of persistence and academic success, differing experiences in higher

education, and their need for academic intervention (Chen & Carroll; 2005;

Engle & Tinto, 2008; Pascarella et al, 2004; Terenzini

et al, 1996). In addition, authors of several qualitative studies suggested

that FG students experienced anxieties from impostor syndrome or feeling like

an outsider (London, 1992; Whitehead & Wright, 2017). In effect, the

dominant mode for discussing FG college students has been through the language

of the deficit model (Valencia, 1997) – framing a population’s differences from

the dominant group as “deficiencies,” and exploring ways to support a

non-dominant population so that they can “overcome” these deficiencies.

Another problematic trend has been the

lack of clarity around the term “first-generation.” First defined in

the Higher Education Act (1965) with the creation of the Federal TRIO programs,

“first-generation college student” originally meant “(A) an individual both of

whose parents did not complete a baccalaureate degree; or (B) in the case of

any individual who regularly resided with and received support from only one

parent, an individual whose only such parent did not complete a baccalaureate

degree” (p. 3-4). However, many researchers and institutions defined

“first-generation” differently: Peralta and Klonowski

(2017) found 9 different definitions for this label, from parents with no

schooling past high school to parents who may have attended a 4-year

institution but did not complete a bachelor's degree. Among policymakers or

school administrators, the term “first-generation” can be used as a catch-all

or substitute phrase for various “underprivileged” identities such as race,

ethnicity, or class (Sharpe, 2017). Other scholars have noted that because the

category “first-generation” is typically constructed in studies as a binary

variable (first-generation vs. continuing-generation), the way “first

generation” is defined can lead researchers to drawing different conclusions

about FG students as a population (Toutkoushian et

al., 2019).

In

the past decade, a growing body of scholarship on FG students has emerged in

the library and information science field. In a critical review of this

literature, Ilett (2019) identified four dominant

themes in discussing FG students: they are presented as (1) outsiders, (2) a

problem, (3) reluctant library users, and (4) capable students. A few

researchers have focused on FG information seeking behaviors. Some researchers

suggested that FG students may prefer different formats of information sources,

such as preferring to use online reference sources (Soria et al., 2015) or

preferring to seek information from peers and pamphlets over advisors and

mentors (Torres et al., 2006). Logan and Pickard (2012) found that FG students

were most likely to seek help from instructors or teaching assistants, and

unlikely to seek help from librarians or family members. Tsai (2012) found

that, when seeking information about coursework, FG students were not likely to

consult family members, but turned to peers instead. FG students in another

study expressed frustration in not only their inability to turn to parents for

information, but also in their perception that for other students, “their

parents are their mentors and they can tell them what to do” (Brinkman et al.,

2013, p. 646). Significantly, however, none of the studies on FG information

seeking directly compared FG students to other populations.

Aims

In

this study, we explored whether information seeking patterns or anxieties

differ between students whose parents have different levels of college

experience. We separated generational status into three variables: FG-no

college (neither parent attended college), FG-attended (one or more parents may

have attended college, but none graduated), and CG (continuing generation, at

least one parent graduated from college). The main research questions were as

follows:

Q1: Do students

report different levels of anxiety in

seeking information on college campuses based on generational status?

Q2: Do students of

different generational statuses report different preferences for information sources about questions related to academics?

Q3: Do students of

different generational statuses report different preferences for information sources about questions related to college life?

Methods

Research

was conducted at two public, four-year residential universities, one in the

Midwestern United States and one in the Eastern United States. The student

population was predominantly white and traditionally aged at both institutions.

At the time the study was conducted, Institution A enrolled approximately

19,000 students, and Institution B enrolled approximately 7,000 students.

Each author disseminated an

online survey at their home institution. The study was reviewed and deemed

exempt by both institutional review boards. However, slightly different

sampling methods and tools were used based on the tools and protocols available

to each institution. At Institution A, the Office of Institutional Research

prepared a randomized sample of 2000 undergraduate participants with a 200%

oversampling of FG students in order to ensure that enough FG students were

included in the sample. To encourage participation in the survey, students were

eligible to win one of five $50 Amazon gift cards. Prior to data cleaning, 326

initial responses were collected, for a response rate of 16%. Data were

collected in Qualtrics. At Institution B, the Office of Research and

Institutional Assessment provided a population list of all 6,305 enrolled

undergraduate students. Through this method, 208 initial responses were

collected for a response rate of 3%. Data were collected in Google Forms.

Surveys and follow-up emails were sent at the end of the fall semester and at

the beginning of the spring semester at both institutions. Data were imported

into SPSS for analysis.

Instrumentation

Demographics

Eight demographic questions were collected in this study:

participants’ year in school, age, gender, whether they identified as an

international student, whether they had a sibling who attended college before

them, parental level of education, self-reported estimated grade point average

(GPA), and major.

Generational

Status

Student responses to the

demographic question on the highest level of parental education were re-coded

into the following three variables in order to avoid a binary variable for

generational status, while still maintaining a large enough sample size in each

category to conduct valid tests:

● First-Generation, No College (FG-NC):

Students who reported that neither parent attended college

● First-Generation, Attended

(FG-A):

Students whose parents may have attended college, but did not graduate

● Continuing-Generation (CG):

Students who reported at least one parent who graduated from college

Information

Seeking Behaviors

Twenty-six exploratory survey

questions (see Appendix) regarding information seeking were developed from data

collected in a qualitative study by Brinkman et al. (2013).

● College Information Seeking Anxiety. Four

questions about student anxiety levels about information seeking on campus were

based on recurring statements made by students who participated in the previous

qualitative study. Students were asked to rate their agreement with four

statements on a Likert scale from 0-10. Two statements were framed positively

and two statements were framed negatively.

● College Information Sources. Twenty-two

questions concerning information sources were also included. One set of 11

questions asked students to use a 5-point Likert scale to rate their likelihood

of seeking help from specific information sources when seeking information

about academics. The other set of 11 questions asked students to use a 5-point

Likert scale to rate their likelihood of seeking help from the same set of

information sources if they were seeking information about college life.

Results

The

initial data set included 534 participants. Through data-cleaning procedures,

we identified 44 participants who skipped more than 10% of the survey. These

cases were excluded listwise, yielding a final data set of 490 responses, with

59.4% (n = 291) from Institution A

and 40.6% (n = 199) from Institution

B. Students were distributed across by year in college (19.7% first year, 24%

sophomore, 23.2% junior, 32.8% senior, and 0.4% “other”). The majority of

respondents (71%) identified as female and reported their age range as 18-22

years old (88.5%). A portion of students (40.6%) indicated that they had an

older sibling who attended college before them. The majority of students were high

achievers: 38.4% of students reported a cumulative GPA of 3.5 or higher, and an

additional 34.7% reported a GPA between 3.0 and 3.49. Based on the highest

reported level of education by their parents, 20.5% of students (n=100) were coded as first- generation,

no college (FG-NC), 16.4% (n=80) as

first-generation, attended (FG-A), and 63.1% (n=308) as continuing-generation (CG).

College

Information Seeking Anxiety Levels by Generational Status

|

Means based on Generational Status |

|||||

|

|

FG-NC |

FG-A |

CG |

Total |

F-Test |

|

I don't know

who to turn to if I have questions about college |

3.36 (2.16) |

3.51 (2.28) |

3.67 (2.28) |

3.58 (2.26) |

F(2, 477) = .75, p = .48 |

|

Other students

around me know more about college than I do |

5.18 (2.54) |

5.43 (2.31) |

5.25 (2.39) |

5.27 (2.41) |

F(2, 465) = .24, p = .79 |

|

People on

campus are not helpful when I ask them questions |

3.76 (2.27) |

3.87 (2.09) |

4.15 (2.08) |

4.02 (2.12) |

F(2, 449) = 1.44, p = .24 |

|

It is

difficult to navigate the system in college |

4.74 (2.44) |

5.06 (2.53) |

4.96 (2.48) |

4.93 (2.47) |

F(2, 476) = .41, p = .66 |

Figure

1

Agreement

with Q4 “It is difficult to navigate the system in college”: interaction of

generational status and year in school.

College

Information Seeking Anxiety

After calculating the mean, an

initial one-way ANOVA was used to explore the relationship of generational

status on college information seeking anxiety. No significant effects were

found, and students reported low-to-medium levels of anxiety overall. Table 1

summarizes means, standard deviations, and overall effects.

Because we sampled students

across four years in college and from two institutions, a series of three-way

ANOVAs were conducted to explore the main effects of generational status and

the interaction effect between generational status, institution, and year in

college on college information seeking anxiety variables. While no significant

three-way interactions between all three variables of generational status,

institution, and year in school were found for any of the questions, a two-way

interaction involving generational status and year in school was found for

Question 4 (“It is difficult to navigate the system in college”), F(6, 453) = 2.322,

p = .03. Specifically, FG-NC students

reported the lowest levels of difficulty navigating the system during their

first year M = 3.47 (SD = 1.77) and

the highest levels of difficulty during their second year M = 5.42 (SD = 2.59), decreased difficulty in their third year M = 4.56 (SD = 2.35), and increased

difficulty again in their final year M

= 5.03 (SD = 2.53). FG-A students displayed a similar pattern to CG students

for the first three years of college, with decreasing levels of reported

difficulty in navigating the system with each passing year. However, in their

final year of college, FG-A students reported a sharp increase in difficulty

navigating the system M = 5.32 (SD =

2.77), whereas CG students continued to report lower levels of difficulty in

navigating the system M = 4.43 (SD =

2.58). Figure 1 illustrates these differences.

Table 2

One-Way

ANOVA Results Across Academic Information Source Variables

|

Means based on

Generational Status |

|||||

|

|

FG-NC |

FG-A |

CG |

Total |

F-Test |

|

Parent |

2.16 (1.30) |

2.74 (1.43) |

3.50 (1.33) |

3.10 (1.45) |

F(2,

485) = 40.89, p < .01* |

|

Friend |

3.62 (1.17) |

3.90 (.89) |

4.08 (.85) |

3.95 (.95) |

F(2,

483) = 9.13, p < .01* |

|

Other

Relative |

2.60 (1.41) |

2.48 (1.28) |

2.47 (1.22) |

2.50 (1.27) |

F(2,

481) = .43, p = .65 |

|

Professor |

4.41 (.85) |

4.38 (.70) |

4.37 (.70) |

4.38 (.74) |

F(2,

483) = .10, p = .91 |

|

Academic

Advisor |

4.10 (1.10) |

3.89 (1.34) |

3.95 (1.23) |

3.97 (1.22) |

F(2,

482) = .77, p = .46 |

|

Resident

Advisor |

2.20 (1.31) |

2.48 (1.33) |

2.37 (1.25) |

2.36 (1.28) |

F(2,

484) = 1.12, p = .33 |

|

Librarian |

2.66 (1.30) |

2.68 (1.34) |

2.30 (1.12) |

2.43 (1.21) |

F(2,

485) = 5.47, p < .01* |

|

Tutoring

Center |

2.78 (1.28) |

2.69 (1.31) |

2.37 (1.19) |

2.51 (1.24) |

F(2,

483) = 5.22, p < .01* |

|

Coworker

or Supervisor |

2.51 (1.40) |

2.58 (1.24) |

2.46 (1.22) |

2.49 (1.26) |

F(2,

480) = .25, p = .78 |

|

I

would look it up on my own |

3.69 (1.30) |

3.68 (1.17) |

3.50 (1.24) |

3.57 (1.24) |

F(2,

482) = 1.22, p = .30 |

|

Other |

2.46 (1.24) |

2.33 (.96) |

2.14 (1.16) |

2.26 (1.15) |

F(2,

172) = 1.31, p = .27 |

*

Significant at the 0.01 level

College

Information Sources: Academic Information

Students were asked to rate their

likelihood of consulting with ten potential information sources when they had

questions about academics. They were also given the opportunity to select other

and write in a response. The most common write-in response was a synonym of

“spouse/partner” (n=4), but the majority of students selecting other

left the write-in section blank. We used a one-way ANOVA to examine the effect

of generational status across the ten information source variables.

Generational status had a significant overall effect on whether students were

likely to consult the following sources for academic information: Parents F(2, 485) = 40.89,

p < .01, Friends F(2, 483) = 9.13, p < .01, Librarians F(2,

485) = 5.47, p < .01 and Tutoring

Centers F(2, 483) = 5.22, p < .01. Table 2 summarizes means,

standard deviations, and ANOVA results.

We used a series of three-way

ANOVAs to examine whether institution or year in college interacted with

generational status on likely academic information sources. No significant

three-way interactions were observed for any academic information source

variables. However, significant two-way interactions with generational status

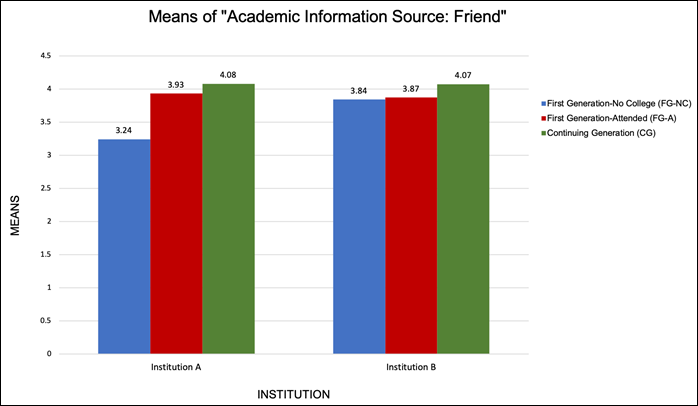

and institution were found for the variables “Friend” F(2, 460) = 5.089, p = .007 and

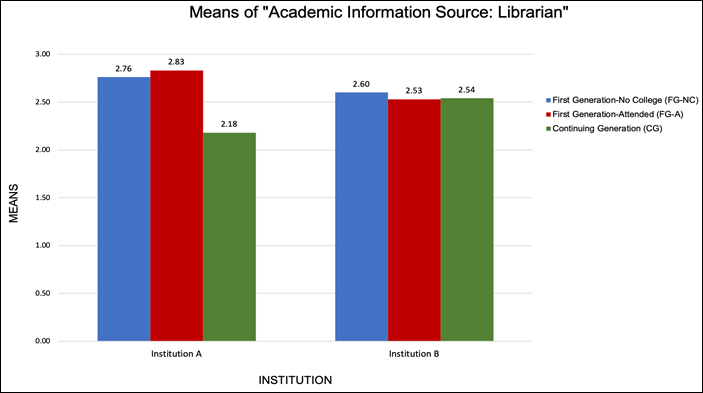

“Librarian” F(2, 462) = 3.306, p = .038. Figure 2 illustrates that

FG-NC students at Institution A were significantly less likely to consult with

friends for academic information (M =

3.24, SD = 1.36) than FG-NC students at Institution B (M = 3.84, SD = .99). There were no significant differences between

institutions for FG-A students (Institution A M = 3.93, SD = .99; Institution B M = 3.87, SD = .81) or CG students (Institution A M = 4.08, SD .84; Institution B M = 4.07, SD = .88).

For the variable “Librarian,”

Figure 3 illustrates that CG students at Institution A were far less likely to

ask a librarian for help with academic information (M = 2.18, SD = 1.01) than CG students from Institution B (M = 2.54, SD = 1.18). Furthermore, both

FG-NC and FG-A students at Institution A (FG-NC M= 2.76, SD = 1.42, FG-A M

= 2.83, SD = 1.26) were more likely to consult with a librarian as an

institutional source than similar groups of students at Institution B (FG-NC M = 2.60, SD = 1.24, FG-A M = 2.53, SD 1.33).

Figure

2

Likelihood

of asking a friend for academic information: interaction of generational status

and institution.

Figure

3

Likelihood

of asking a librarian for academic information: interaction of generational

status and institution.

Table

3

One-Way

ANOVA Results Across College Life Information Source Variables

|

Means based on

Generational Status |

|||||

|

|

FG-NC |

FG-A |

CG |

Total |

F-Test |

|

Parent |

2.22 (1.40) |

2.54 (1.39) |

3.31 (1.36) |

2.96 (1.45) |

F(2,

484) = 28.135, p < .001** |

|

Friend |

3.93 (1.23) |

4.35 (.87) |

4.55 (.65) |

4.39 (.87) |

F(2,

484) = 21.223, p < .001** |

|

Other

Relative |

2.53 (1.41) |

2.65 (1.29) |

2.79 (1.36) |

2.71 (1.36) |

F(2,

481) = 1.557, p = .212 |

|

Professor |

2.78 (1.35) |

2.59 (1.25) |

2.40 (1.07) |

2.51 (1.17) |

F(2,

482) = 4.144, p = .016* |

|

Academic

Advisor |

2.71 (1.36) |

2.46 (1.23) |

2.34 (1.16) |

2.43 (1.22) |

F(2,

483) = 3.596, p = .028* |

|

Resident

Advisor |

2.57 (1.52) |

2.90 (1.52) |

2.80 (1.32) |

2.77 (1.40) |

F(2,

481) = 1.451, p = .235 |

|

Librarian |

2.06 (1.14) |

1.81 (.98) |

1.65 (.86) |

1.76 (.95) |

F(2,

482) = 7.792, p = .001** |

|

Tutoring

Center |

2.08 (1.14) |

1.75 (.97) |

1.65 (.87) |

1.75 (.96) |

F(2,

481) = 7.792, p < .001** |

|

Coworker

or Supervisor |

2.64 (1.45) |

2.85 (1.38) |

2.53 (1.26) |

2.60 (1.32) |

F(2,

482) = 1.871, p = .155 |

|

I

would look it up on my own |

3.52 (1.46) |

3.40 (1.25) |

3.40 (1.23) |

3.42 (1.28) |

F(2,

481) = .316, p = .729 |

|

Other |

2.36 (1.24) |

2.52 (1.15) |

2.13 (1.09) |

2.27 (1.15) |

F(2,

157) = 1.506, p = .225 |

*

Significant at the 0.05 level

**

Significant at the 0.01 level

College

Information Sources: College Life Information

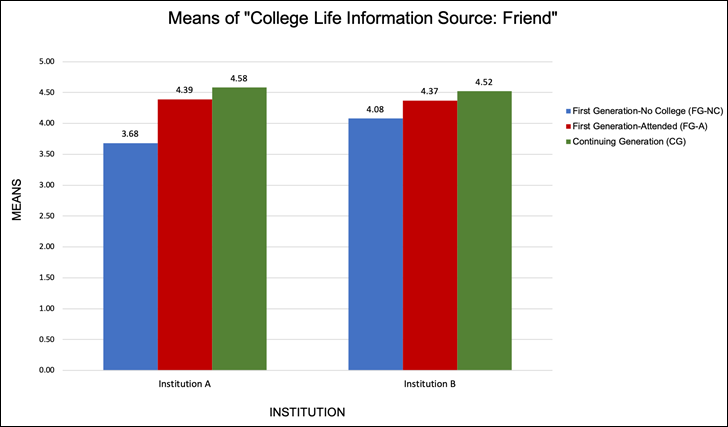

The next set of questions asked

students to rate their likelihood of consulting with an information source when

seeking information about college life. We used a one-way ANOVA to examine the

effect of generational status across information source variables. Significant

differences were found for multiple variables. Students whose parents had less

college experience were less likely to turn to parents F(2, 484) = 28.135, p

< .001 and friends F(2, 484) =

21.223, p < .001 for information

about college life, but more likely to turn to professors F(2, 482) = 4.144, p =

.016, academic advisors F(2, 483) =

3.596, p = .028, librarians F(2, 482) = 7.792, p = .001, and the tutoring center F(2, 481) = 7.792, p <

.001. Table 3 summarizes means, standard deviations, and ANOVA results.

Interactions between generational

status and institution or year in college were also explored through a series

of three-way ANOVAs. A two-way interaction between generational status and

institution was significant for the variable “Friend” F(2, 461) = 3.204, p = 0.42.

Specifically, FG-NC students at Institution A were less likely to consult with

friends for college life information (M

= 3.68, SD = 1.31) than FG-NC students at Institution B (M = 4.08, SD = 1.26). See Figure 4.

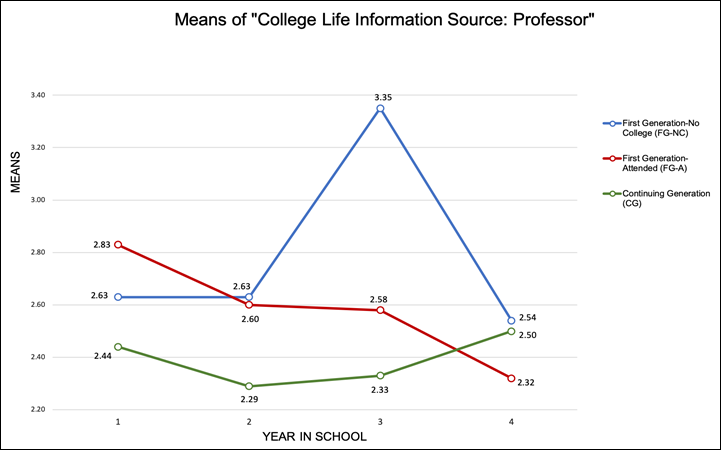

A two-way interaction was also

found for generational status and year in school for the likelihood of asking a

professor for college life information F(6, 458) = 2.385, p = .028. Figure 5 illustrates how FG-NC,

FG-A, and CG students reported different patterns of behavior by year. FG-NC

students were most likely to consult with professors in their junior year (M = 3.35, SD = 1.23) but least likely in

their senior year (M = 2.54, SD =

1.30). FG-A students followed a different pattern, and were most likely to

consult with professors in their first year (M = 2.83, SD = 1.38) declining each year to their senior year (M = 2.32, SD = 1.29). CG students,

however, were the most likely to consult with professors during their senior

year (M = 2.50, SD = 1.19).

Finally, a two-way interaction

was found between generational status and year in school for the variable

“Academic Advisor” F(6,

460) = 2.555, p = .019. See Figure 6. FG-NC students reported a significantly

higher likelihood (M = 3.35, SD =

1.33) of consulting with an academic advisor for college life information in

their junior year, whereas FG-A and CG students reported declining or flat

likelihood of asking an academic advisor for college life information as they

advanced toward their senior year.

Figure

4

Likelihood

of asking a friend for college life information: interaction of generational

status and institution.

Figure

5

Likelihood

of asking a professor for college life information: interaction of generational

status and year in school.

Figure

6

Likelihood

of asking an academic advisor for college life information: interaction of

generational status and year in school.

Discussion

Information

Seeking Anxiety

The

main purpose of this study was to determine if generational status had any

effect on college student information seeking anxiety and sources. In contrast

with previous studies that suggested that FG students may have experienced

increased anxiety or feelings of impostor syndrome (Brinkman et al., 2013;

London, 1989; Whitehead & Wright, 2017) in this study we did not find that

FG students reported higher anxiety overall about information seeking than

their CG peers. On only one information seeking anxiety variable (the statement

“it is difficult to navigate the system in college”) did the responses of FG-NC

students follow a different curve than those of other students: FG-NC students

did not find the “system” in college to be particularly difficult to navigate

in their first year, whereas FG-A and CG students thought college was the most

difficult to navigate in their first year. In their second year, however, FG-NC

students reported much higher levels of anxiety about navigating the system in

college while other groups reported decreasing levels of concern. Finally, both

FG-NC and FG-A students found navigating the system more difficult in their

senior year.

The

Dunning-Kruger Effect provides one potential explanation for the variation in

FG student responses over time. With this theory, Kruger and Dunning (1999)

described how individuals who lacked “competence” or expertise in a domain

tended to lack the metacognitive skills in evaluating their own performance, and

consequently tended also to be overly optimistic and confident in their

abilities in that domain. In the current study, FG-NC may have reported very

low levels of concern about navigating the system in college because they

didn’t know enough about what there was to navigate, whereas other groups of

students with more familial knowledge about the college system might have less

confidence. This may have been particularly true for first-year students in

this particular study, since the surveys were sent at the end of the students’

fall semester, with follow-up emails sent at the beginning of the spring

semester. Therefore, students would have only had one semester of experience in

trying to “navigate the system in college” on which to base their responses. By

their sophomore year, students had more time to develop awareness of the nature

of the domain (navigating the system in college), and therefore their

evaluation of their abilities to navigate that domain changed and they became

less confident. However, further research would be needed to establish such

links.

The

overall result that FG students showed no more agreement with the information

seeking anxiety statements than CG students was surprising, because the

statements for the current study were formed from Brinkman et al.’s (2013)

qualitative study on FG students, in which “many first-generation students

perceived that other students could ask their parents when they had questions

about the ‘big picture’ of navigating college life, whereas they could not” (p.

648). In other qualitative studies based on interviews and focus groups, FG

students reported feeling like “outsiders,” or lacking information or capital

when compared with non-FG students (Bergerson, 2007;

Cushman, 2007; London, 1992). While the current study does not disprove these

previous studies, we do suggest that FG students may have internalized a sense

of deficit that they have then attributed to their identity as

first-generation. This phenomenon is interesting and worthy of future research,

as other studies have suggested that the “first-generation college student”

identity is a relatively newly formed identity for FG students in comparison to

other intersecting identities such as race, gender, and class (Orbe, 2004). FG students are continually forming and

performing this new identity while in college and, if their identity as a

“college student” is still relatively weak, they may therefore experience

impostor syndrome (Whitehead & Wright, 2017). It is possible that

intervention efforts targeted to FG students that emphasize deficits in

information, experience, or capital may increase FG students’ internalization

of deficit thinking and impede their ability to form strong identities as FG

students who “belong” in college, thus causing them to feel that other students

know more about college, or fit in better, than they do. More research is

needed to explore these potential connections.

Information

Seeking Sources

In

this study, we confirmed previous research that parents are a low information

source for FG students (Logan & Pickard, 2012; Tsai, 2012). However, while

previous research has suggested that friends or peers are very high information

sources (Tsai, 2012), we found that compared with continuing-generation

students, FG students were less likely to ask their peers for both academic or

college life information. There may be several reasons for this. For example,

if an institution offers highly visible alternative support programs or

information pathways specifically for FG students, this may also alter the

likelihood of FG students consulting with their peers for information. At both

institutions in this study, FG students reported being more likely to seek

information (both academic and non-academic) from the campus Tutoring Center. If

a campus makes tutoring services more visible to this population, then this can

explain why FG students would report seeing this service as a resource. The

same phenomenon can be observed with librarians: FG students at Institution A

also reported being more likely to consult with librarians for academic

information than their CG peers. This runs counter to previous studies that

suggested that FG students were reluctant library users (Ilett,

2019; Logan & Pickard, 2012; Long, 2011). Intervention efforts by

librarians may explain some of these differences: at Institution A, librarians

had been involved for several years in campus wide programs and courses aimed

at FG students, including offering FG-specific orientations.

However,

the visibility of resources such as tutoring services or library services does

not alone explain why FG students might be less likely to ask their friends for

information about college life or academics. As evidenced in Figures 2 and 5,

the most pronounced difference in seeking information from friends was in FG

students from families with no college experience (FG-NC) at Institution A.

Campus culture may also provide an important explanation for the reason why FG

students at one institution may be less likely to ask their friends for

information about college. Institution A is a more selective university, has a

small overall percentage of FG students in their total student body, and also

has a considerable percentage of “legacy” students (meaning their parents,

siblings, or other relatives attended the university). In research on FG

identity, Orbe (2004) suggested that for some FG

students, “especially those who were attending more selective universities,

coming from a family without college degrees was ‘embarrassing’” (p. 143). Thus,

FG students at Institution A who felt themselves to be in a minority group may

have felt reluctant to disclose to their peers that they lacked knowledge about

college, and may have consequently sought alternative pathways to information,

such as librarians, tutors, or other support services. FG students at

Institution B, on the other hand, may not have felt as different or

marginalized in comparison to their peers, and may therefore have felt more

comfortable asking their peers for information.

We

also found an inverse relationship with parental experience in college and the

likelihood of students turning to academic sources, such as professors,

advisors, librarians, and tutors, for non-academic information about college

life. This finding was similar to that of Given (2002) in a study of mature

undergraduate students, who tended to turn to on-campus academic sources for

everyday life information seeking needs such as childcare. We also found an

interesting pattern, where FG-NC students were mostly likely to report seeking

information about college life from an academic source (professor or academic

advisor) in their junior year. Brinkman et al. (2013) suggested that some

students felt a “perceived a lack of follow-up” with campus support systems after

their first and second year (pp. 645-646), which, if true, may partially

explain why students would turn to alternative sources of information in their

junior year. An alternative explanation could be that students by their junior

year were more embedded into their major field of study and had identified

faculty members who had become their mentors. A third explanation could be that

students would be more likely to be living in off-campus housing starting in

their third year, particularly at Institution A, which had a two-year

residential requirement. Further research would be needed to establish the

motivations of students for seeking out non-academic information from academic

sources at specific years in their college career, as well as to establish what

kinds of non-academic information was being sought.

Limitations

Although

this study extends existing literature on information seeking behavior in

first-generation college students, there are several limitations. First, data

were collected from self-report surveys that, while based on previous

qualitative research, were not validated. There was no way to verify the

accuracy of a participant’s response. Data were collected from two

predominantly white four-year public institutions from the Midwest and East. It

is possible that these results may not generalize to institutions that have

different demographic or geographic compositions, and may also not generalize

to two-year institutions. Finally, the survey did not account for the growing

use of social media and unofficial information networks such as Reddit or

online communities for information that have increased in popularity since this

study was conducted. Future studies should take these networks into account

more rigorously.

Conclusions and

Directions for Future Research

In this study, we found that there were no

general differences in information seeking anxiety between students whose

parents had differing levels of experience with college. However, one variable

exposed that students who were the first in their family to go to college

experienced levels of anxiety about “navigating the system in college” during

very different times than their peers. We confirmed that first-generation

students consulted with their parents far less than their continuing-generation

peers. We also found that institutional or generational differences may

influence whether students ask for information from their peers, librarians,

tutoring centers, professors, or advisors.

The results of this study have several

possible implications for library practice. Most broadly, this research

demonstrated that framing services and support for FG students as “at risk” can

be problematic at best, and can also be counterproductive or marginalizing.

This research is part of a growing body of literature calling for more critical

reflection on inclusive library practice. Rather than creating prescriptive

programming that reinforces an “at risk” narrative for FG students, libraries

and librarians have an opportunity to engage FG students more holistically. For

both authors, this current research has influenced how we approach instruction

to focus more on metacognitive aspects of information literacy based on the

students’ learning experiences and a reflection on their understanding. In

practice, this might translate to an increase in reflective activities in a

library session, enabling the librarian to adapt their lesson in response to

the student learning experience. Shifting to a more responsive instructional

practice creates a space for the student holistically and avoids transactional,

“banking” models of pedagogy (Freire, 2000).

The other important takeaway from this

study is that FG students are not a homogenous group; rather, they are

negotiating their identities and navigational strategies within a campus culture

over time. It is important for librarians to understand their own institutional

culture and context, whether it is in learning more about campus demographics

as a whole, or in identifying groups on campus that are already providing

services for FG students. In a 2019 paper, Brinkman, Natale, and Smith

discussed examples of how libraries can collaborate with student affairs units

in promoting existing programs that celebrate FG identity, or can situate

library services in a larger context of resources for student success. As an

example, one author of this paper was invited to staff a library table at a

campus-wide “first-gen day” event. Rather than using the table to distribute

library brochures, the table became a zine-making workshop station, covered

with magazines, scissors, glue, stencils, pens, and pencils. Students were

invited to make a page for a collaborative zine on “what first-gen means to

me,” which was then included in the university archives and distributed

digitally to contributors and participants. In the course of inviting students

to become authors of their own unique stories and then archiving them, FG

students and library staff had the opportunity to converse about other library

services. This example demonstrates the effectiveness of creating programming

specifically for FG students that is aligned with campus outreach activities,

while also celebrating students’ identity holistically.

This study also exposed several areas for

further research. One particular line of inquiry is that of the intersections

of information seeking, first-generation identity formation, and campus

culture. The current research suggested that FG students do lack a major

pathway (parents) that continuing-generation students use for academic and

non-academic information. Interventions may help forge alternative pathways for

such information. At the same time, interventions – especially if framed in the

language of deficit - may reinforce a campus culture where FG students may feel

singled out, or choose not to disclose their FG identity to their peers for

risk of embarrassment, or alternatively, may cause FG students to internalize a

sense of deficit (Orbe, 2004). Framing interventions

through other approaches, such as “funds of knowledge” approaches (Ilett, 2019), strengthening FG students’ identity as

“college students” by presenting college as a path to “something greater” than

college itself (Whitehead & Wright, 2017), or placing more value on the

capital that FG students possess rather than the capital they lack (Bergerson, 2007), may be helpful areas of future

investigation.

References

Bergerson, A. A. (2007).

Exploring the impact of social class on adjustment to college: Anna’s story. International Journal of Qualitative Studies

in Education, 20(1), 99–119. https://doi.org/10.1080/09518390600923610

Brinkman,

S., Gibson, K., & Presnell, J. (2013, April

10-13). When the helicopters are silent: The information

seeking strategies of first-generation college students [Paper presentation]. Association of College & Research Libraries

2013 Conference, Indianapolis, IN, United States. http://www.ala.org/acrl/sites/ala.org.acrl/files/content/conferences/confsandpreconfs/2013/papers/BrinkmanGibsonPresnell_When.pdf

Brinkman, S., Natale,

J., & Smith, J. (2019). Meeting them where

they are: Campus and library support strategies for first-generation students.

In N-Y. Tran & S. Higgins (Eds.), Supporting today’s students in the library:

Strategies for retaining and graduating international, transfer,

first-generation, and re-entry students (pp. 185-198). ACRL.

Center

for First-Generation Student Success. (2019). First-generation college students: Demographic characteristics and

postsecondary enrollment. https://firstgen.naspa.org/files/dmfile/FactSheet-01.pdf

Chen,

X., & Carroll, C. D. (2005). First-generation

students in postsecondary education: A look at their college transcripts.

Postsecondary education descriptive analysis report. NCES 2005-171 (ED485756). ERIC. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED485756.pdf

Choy,

S. (2001). Students whose parents did not

go to college: Postsecondary access, persistence, and attainment (NCES

2001–126). National Center for Education Statistics. https://nces.ed.gov/pubs2001/2001126.pdf

Cushman,

K. (2007). Facing the culture shock of college. Educational Leadership, 64(7),

44–47.

Engle,

J., & Tinto, V. (2008). Moving beyond access: College success for

low-income, first-generation students (ED504448). ERIC. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED504448.pdf

Freire, P. (2000). Pedagogy of the

oppressed, 30th anniversary edition (M. B. Ramos, Trans.). Bloomsbury.

(Original work published 1968)

Given, L. M. (2002). The academic and the everyday:

Investigating the overlap in mature undergraduates’ information–seeking

behaviors. Library & Information Science Research, 24(1),

17–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0740-8188(01)00102-5

Higher Education

Act of 1965, 20 U.S.C. ch. 28, subch.

IV, Part A § 1070a–11(1965). https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/STATUTE-79/pdf/STATUTE-79-Pg1219.pdf

Ilett, D. (2019). A

critical review of LIS literature on first-generation students. portal: Libraries and the Academy, 19(1), 177–196. https://doi.org/10.1353/pla.2019.0009

Kruger,

J., & Dunning, D. (1999). Unskilled and unaware of it: How difficulties in

recognizing one’s own incompetence lead to inflated self-assessments. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology,

77(6), 1121–1134. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.77.6.1121

Logan,

F., & Pickard, E. (2012). First-generation college students: A sketch of

their research process. In L. M. Duke & A. D. Asher (Eds.), College libraries and student culture: What

we now know (pp. 1–208). ALA Editions.

London, H. B. (1989). Breaking away: A

study of first-generation college students and their families. American

Journal of Education, 97(2), 144–170.

London, H. B. (1992). Transformations: Cultural

challenges faced by first-generation students. New Directions for Community

Colleges, 1992(80), 5-11. https://doi.org/10.1002/cc.36819928003

Long,

D. (2011). Latino students’ perceptions of the academic library. The Journal of Academic Librarianship, 37(6), 504–511. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2011.07.007

Nunez,

A-M., & Cuccaro-Alamin, S. (1998). First-generation students: Undergraduates

whose parents never enrolled in postsecondary education (NCES 98-082).

National Center for Education Statistics. https://nces.ed.gov/pubs98/98082.pdf

Orbe, M. P. (2004). Negotiating

multiple identities within multiple frames: An analysis of first‐generation

college students. Communication Education,

53(2), 131–149. https://doi.org/10.1080/03634520410001682401

Pascarella,

E. T., Pierson, C. T., Wolniak, G. C., & Terenzini, P. T. (2004). First-generation college students:

Additional evidence on college experiences and outcomes. The Journal of Higher Education, 75(3), 249–284. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221546.2004.11772256

Peralta,

K. J., & Klonowski, M. (2017). Examining

conceptual and operational definitions of “first-generation college student” in

research on retention. Journal of College

Student Development, 58(4),

630–636. https://doi.org/10.1353/csd.2017.0048

Sharpe,

R. (2017, November 3). Are you first gen? Depends on

who’s asking. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2017/11/03/education/edlife/first-generation-college-admissions.html

Soria,

K. M., Nackerud, S., & Peterson, K. (2015).

Socioeconomic indicators associated with first-year college students’ use of

academic libraries. The Journal of

Academic Librarianship, 41(5),

636–643. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2015.06.011

Terenzini, P. T.,

Springer, L., Yaeger, P. M., Pascarella, E. T., & Nora, A. (1996).

First-generation college students: Characteristics, experiences, and cognitive

development. Research in Higher Education, 37(1), 1–22.

Torres,

V., Reiser, A., LePeau, L., Davis, L., & Ruder,

J. (2006). A model of first-generation Latino/a college students’ approach to

seeking academic information. NACADA

Journal, 26(2), 65–70. https://doi.org/10.12930/0271-9517-26.2.65

Toutkoushian, R. K., May-Trifiletti, J. A., & Clayton, A. B. (2019). From “first

in family” to “first to finish”: Does college graduation vary by how

first-generation college status is defined? Educational

Policy. Advance online

publication. https://doi.org/10.1177/0895904818823753

Tsai,

T-I. (2012). Coursework-related information horizons of first-generation

college students. Information Research,

17(4). http://informationr.net/ir/17-4/paper542.html#.XvIu0mo3nOQ

United States Census Bureau. (2017, March 30). Highest educational levels reached by

adults in the U.S. since 1940 [Press

release].

https://www.census.gov/newsroom/press-releases/2017/cb17-51.html

Valencia,

R. R. (1997). The evolution of deficit

thinking: Educational thought and practice. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203046586

Whitehead,

P. M., & Wright, R. (2017). Becoming a college student: An empirical

phenomenological analysis of first generation college

students. Community College Journal of

Research and Practice, 41(10),

639–651. https://doi.org/10.1080/10668926.2016.1216474

Appendix

College Information Seeking Anxiety

How much do you

agree with the following statements?

0 = do not agree

5 = neither agree nor disagree

10 = agree completely

|

|

0 |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

10 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Reverse-code

responses to statements 1 and 3

College Information Sources

If you had a question about academics in college, how likely

are you to seek help from…

|

|

Very Unlikely (1) |

Unlikely (2) |

Undecided (3) |

Likely (4) |

Very Likely (5) |

|

Parents (1) |

m |

m |

m |

m |

m |

|

Friends (2) |

m |

m |

m |

m |

m |

|

Other relatives (3) |

m |

m |

m |

m |

m |

|

Professors (4) |

m |

m |

m |

m |

m |

|

Academic Advisor (5) |

m |

m |

m |

m |

m |

|

Residence Advisor (RA) (6) |

m |

m |

m |

m |

m |

|

Library (7) |

m |

m |

m |

m |

m |

|

TUtoring Center (8) |

m |

m |

m |

m |

m |

|

Coworker or supervisor (9) |

m |

m |

m |

m |

m |

|

|

m |

m |

m |

m |

m |

|

Other (specify) |

m |

m |

m |

m |

m |

1 = low information source

5 = high information source

If you had a question about college life, how likely are you

to seek help from…

|

|

Very Unlikely (1) |

Unlikely (2) |

Undecided (3) |

Likely (4) |

Very Likely (5) |

|

Parents (1) |

m |

m |

m |

m |

m |

|

Friends (2) |

m |

m |

m |

m |

m |

|

Other relatives (3) |

m |

m |

m |

m |

m |

|

Professors (4) |

m |

m |

m |

m |

m |

|

Academic Advisor (5) |

m |

m |

m |

m |

m |

|

Residence Advisor (RA) (6) |

m |

m |

m |

m |

m |

|

Library (7) |

m |

m |

m |

m |

m |

|

Tutoring Center (8) |

m |

m |

m |

m |

m |

|

Coworker or supervisor (9) |

m |

m |

m |

m |

m |

|

No one – I would look it up on my own (10) |

m |

m |

m |

m |

m |

|

Other (specify) |

m |

m |

m |

m |

m |

- 1 = low information

source

- 5 = high information

source