Review Article

Does the READ Scale Work for Chat? A Review of the Literature

Adrienne Warner

Assistant Professor, Learning

Services Librarian

University of New Mexico

Albuquerque, New Mexico, United

States of America

Email: adriennew@unm.edu

David A. Hurley

Discovery and Web Librarian

University of New Mexico

Albuquerque, New Mexico, United

States of America

Email: dah@unm.edu

Received: 29 Mar. 2021 Accepted: 13 May 2021

![]() 2021 Warner and Hurley. This

is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

2021 Warner and Hurley. This

is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

DOI: 10.18438/eblip29947

Abstract

Objective – This review aims

to determine the suitability of the READ Scale for chat service assessment. We

investigated how librarians rate chats and their interpretations of the

results, and compared these findings to the original purpose of the Scale.

Methods – We performed a

systematic search of databases in order to retrieve sources, applied inclusion

and exclusion criteria, and read the remaining articles. We synthesized common

themes that emerged into a discussion of the use of the READ Scale to assess

chat service. Additionally, we compiled READ Scale designations across

institutions to allow side-by-side comparisons of ratings of chat interactions.

Results – This review

revealed that librarians used a variety of approaches in applying and

understanding READ Scale ratings. Determination of staffing levels was often

the primary goal. Further, librarians consistently rated chat interactions in

the lower two-thirds of the scale, which has implications for service

perception and recommendations.

Conclusion – The

findings of this review indicated that librarians frequently use READ Scale

data to make staffing recommendations, both in terms of numbers of staff

providing chat service and level of experience to adequately meet service

demand. Evidence suggested, however, that characteristics of the scale itself

may lead to a distorted understanding of chat service, skewing designations to

the lower end of the scale, and undervaluing the service.

Introduction

Researchers have been strategizing for decades about how

best to capture what happens in reference interactions. The Reference Effort

Assessment Data (READ) Scale (Gerlich & Berard, 2007) was one of several tools developed in

response to librarians’ “deep dissatisfaction” (Novotny, 2002, p. 10) with the

reference statistics being collected in the early 2000s. The then-common

practice was to record simple counts, often as hash marks on paper, for each

mode (e.g., desk or telephone) in one of two categories: “directional” or

“reference”. The READ Scale, by contrast, is a six-point scale indicating the

amount of effort a librarian expends on each reference interaction. Answers are

rated 1 if they require no specialized knowledge or consultation of resources.

A rating of 6 indicates “staff may be providing in-depth research and services

for specific needs of the clients” (Gerlich, n.d.).

In introducing the READ Scale, Gerlich and Berard (2007) emphasized that their goal was to change the

focus from “how many” and “what kind” to the knowledge, skills, and abilities

needed to provide the service. They suggested this data could be used for “a

retooling of staffing strategies,” to “increase positive self-awareness of the

professional librarian” (2007, p. 9) and “for training and continuing

education, renewed personal and professional interest, and reports to

administration" (Gerlich & Whatley, 2009, p.

30). While other classification systems exist (see Maloney & Kemp, 2015,

for examples), the READ Scale has become a standard in many libraries—a state

that is reflected in its integration into both open source and commercial

reference management products (e.g., Sarah, 2012).

Gerlich and Berard (2010) undertook a

large-scale, multi-institution viability study in 2007. However, the data

reflected the predominantly face-to-face nature of reference at that time. With

15 institutions reporting 8,439 transactions, 91% were face-to-face. Chat

transactions accounted for only 1% of the interactions in the study. The

landscape has shifted dramatically since then. Chat is now a major source of

reference transactions in academic libraries (Asher, 2014; Belanger et al.,

2016; Nicol & Crook, 2013; Ward & Phetteplace,

2012), accounting for more than 20 percent of all reference transactions at the

University of New Mexico in 2019, with in-person reference transactions down to

just 55 percent. In 2020, the majority of reference transactions were conducted

via chat, likely due to COVID-19 related building closures.

The

software that mediates chat reference interactions typically generates rich

metadata, from timestamps to transcripts, allowing, and likely encouraging,

innumerable assessment strategies. Indeed, chat reference evaluation has been

the focus of hundreds of research articles since its first implementation in

academic libraries in North America in the mid 1990s (Matteson et al., 2011),

with metrics including number of chat interactions in a given timeframe, number

of missed chats, frequency and length of interaction, turns taken between

librarian and user, word counts, and type of referring URL (Luo, 2008). These

automatically generated metrics are often combined with more qualitative

measures such as types of questions asked; the presence of reference interviews

and instructional elements; and quality, completeness, and tone of librarians’

answers (Luo, 2008).

Some

chat-specific, or at least virtual reference specific, assessment tools have

been developed, both for services overall (Hirko,

2006; White, 2001), and for transcript analysis in particular (Mungin, 2017). However, transcript analysis is both time

consuming (Mungin, 2017) and limited (Belanger et

al., 2016; Rabinowitz, 2021). Much of the literature on chat reference has been

case studies with limited generalizability, with McLaughlin (2011) suggesting

the need for standard approaches and reporting formats across libraries.

There

has been recognition generally that standards and assessments are not

necessarily transferable from face-to-face to online reference (Ronan et al.,

2003), and some researchers have attempted to determine applicability across

modes (Schwartz & Trott, 2014). However, though the READ Scale is widely

used with chat reference, and is recommended as a metric "applicable

across reference services" in the Reference and User Services

Association's Guidelines for Implementing and Maintaining Virtual Reference

Services (2017), no equivalent to the viability study has been undertaken

for chat. Library services have changed considerably in the nearly two decades

since the READ Scale was developed, and it cannot be assumed that a tool

developed for in-person contexts will then be appropriate for chat reference in

2021. In that sense, there is no evidence that the READ Scale is appropriate

for chat. As a first step in investigating the viability of the READ Scale for

chat, we review the literature on chat reference that uses the READ Scale.

Aims

There are several ways in which a literature review can

help us determine the suitability of the READ Scale for chat. First, we gain

insight into how and why librarians are using the READ Scale; that is, we want

to see what librarians using the READ Scale for chat reference are trying to

understand and what decisions they are trying to make with READ Scale data. We

are interested if these are the same uses that Gerlich

and Berard (2007) anticipated, and if the nature of

READ Scale data is appropriate for these uses. Second, we can examine the

ratings that are reported for chat reference across institutions, much as Gerlich and Berard did for all

reference transactions. Here we are interested in the ratings themselves,

including what patterns are evident, but also in any modifications being done

to the READ Scale, as well as how the data are interpreted and reported in the

literature. We use “librarians” to refer to all library workers who provide or

analyze chat service. We use “chat agents” to describe the workers who field

chat in situ, distinguished from those who later analyze trends.

Thus, we have two broad questions to guide our review:

●

How do librarians

use the READ Scale to assess chat?

●

How do librarians

rate chats on the READ Scale?

Taken together, these two strands present a picture of

the READ Scale in practice, and whether or not it is an appropriate tool for

the assessment of chat reference.

Method

We took a systematic approach to collecting pertinent

professional literature using a mixed methods review synthesis (Heyveart et al., 2016). First, we explicitly defined

inclusion and exclusion criteria for the literature we would review. Then we

developed a search strategy to locate literature that would meet our inclusion

criteria. Next, we read the literature to identify themes and patterns, and

iteratively reread and assigned categories until we reached consensus on both

the categories that were present in the literature, and the specific categories

present in each document.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

We defined “professional literature” to include articles,

white papers, book chapters, and conference proceedings and presentations. For

clarity, we use the term “article” to refer to all document types. To be

included, articles must have directly discussed the READ Scale as applied to

chat reference, other than reporting data from a different source, such as in

the literature review section of an article. Exclusion criteria were review

articles that did not present otherwise unpublished data and articles in which

READ Scale data and discussion of chat cannot be distinguished from other modes

of reference. We aimed for a global scope and so explicitly did not exclude

material based on publication language or library type.

Search Strategy

We searched Library & Information Sciences Abstracts

(LISA), Library, Information Science & Technology Abstracts (LISTA),

ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global Full Text Global, Web of Science

Core Collection, Google Scholar, EBSCO Discovery Service (EDS), and the e-LIS

repository. Though platforms vary in the exact construction of searches, our

search had two concepts: the READ Scale and chat reference. While we could be

confident that the presence of the phrase “Reference Effort Assessment Data”

referred to the scale developed for library reference services, not all

relevant documents spelled out the acronym. Further complicating matters, the

phrase “READ Scale” was used in ways that are not related to the READ Scale.

Therefore, our search required either the use of the full name of the scale, or

the acronym and a variation on the word library and the word reference. The

second concept was chat reference, which we defined to include any synchronous

online reference service, such as chat or instant messaging. Because e-LIS,

which does not index full-text, had only one result for “READ Scale” and none

for “Reference Effort Assessment Data”, we did not include that concept in the

query. Instead, our query looked only for the concept of chat reference, and we

manually checked each “Reference work” subject result for the READ Scale

concept.

Table 1

Database Search Strategies

|

Database Database note |

Search |

|

EDSa, LISA, LISTA, ProQuest Dissertations and Theses Full

Text Global, Web of Science Core Collection |

(chat* OR trigger* OR "instant Messag*")

AND (("READ Scale" AND librar*) OR

“Reference Effort Assessment Data”) |

|

Google Scholar |

"Reference Effort Assessment Data" OR

"READ Scale" AND library OR libraries OR librarians AND Reference

AND chat OR "Instant messaging" OR "instant message" |

|

e-LIS |

Field: Keywords Any of: Chat

messaging messenger |

a Every EDS

configuration is unique. While the total number of databases at UNM is in the

hundreds, the databases within our EDS that produced hits on our query were:

Academic Search Complete, Applied Science & Technology Source, British

Library Document Supply Centre Inside Serials & Conference Proceedings,

Business Source Complete, Complementary Index, Directory of Open Access

Journals, Education Research Complete, ERIC, eScholarship,

Gale Academic OneFile, Gale OneFile: Computer Science, Library, Information

Science & Technology Abstracts, ScienceDirect, Social Sciences Citation

Index, and Supplemental Index.

Themes and Patterns

We read each article and noted patterns and themes

related to our guiding questions, including descriptions of how READ was used,

the READ score data itself, and any resultant service outcomes. We were

interested in similarities across institutions as well as differences in

implementation or interpretation.

Results

Our search strategy yielded 141 unique items. After

applying the inclusion and exclusion criteria to the search results, we had a

total of 18 articles that we included in the review. All were from academic

institutions, of which two were outside the United States. The data, patterns,

and themes found in those articles are presented below.

Rating Comparability

Gerlich and Berard (2010), as part of

testing its viability across many institutions, normed READ Scale designations with coordinators at

each institution who then normed the Scale with their local reference agents.

Larson et al. (2014) highlighted consistent application of the scale as an

issue when a chat service employed both local and consortial

chat agents. However, the rest of the articles did not have any

cross-institution norming, though five (in addition to Gerlich

and Berard), performed some form of inter-rater

norming for their own data (Belanger et al., 2016; Kemp et al., 2015; Keyes

& Dworak, 2017; Maloney & Kemp, 2015; Stieve

& Wallace, 2018). In the remainder, no mention was made of any norming of

READ Scale ratings, other than Warner et al. (2020) who explicitly stated that

interrater reliability was not tested as part of the study.

Rating Process

Also potentially limiting the comparability across

institutions is who rated the chats. In eight articles, the ratings were

applied post-hoc by the researchers, in three cases, the reference agents rated

their own interactions, while in six articles, it is not stated who rated the

chats. Kohler (2017) rated chats algorithmically, and compared the ratings to

those done by the chat agents, concluding that the algorithm was as good or

better at rating the effort required by the chat agents than the agents

themselves.

Rating Questions or Answers

Asher (2014), Cabaniss (2015), Maloney and Kemp (2015),

Ward and Phetteplace (2012), and Ward and Jacoby

(2018) used the READ Scale to rate incoming questions, while others looked at

the outbound responses of the librarians: the University of Turin used the

ratings to “uniformly categorize the type of responses our patrons received” (Bungaro et al., 2017, p. 4). Kohler (2017) reported

Rockhurst University used the READ Scale to understand “the effort, skills,

knowledge, teaching, techniques, and tools” used by librarians (p. 138). Keyes

and Dworak (2017), Mavodza

(2019), Stieve and Wallace (2018), Valentine and Moss (2017), and Warner et al.

(2019) did not address whether they were assessing the complexity of either

questions or answers.

Local Adaptations

Five institutions represented in the literature adjusted

the READ Scale. Kohler (2017) added a 0 rating to algorithmically rated

transactions that the algorithm was not able to rate. While these were largely

staff demonstrations, they were included in the analysis. Belanger et al.

(2016) dropped level 6 of the scale before assessment started, though no

rationale was given. Keyes and Dworak (2017) shifted

the scale to 0-5, without explanation. No articles mentioned adjustments to

extend the scale beyond level 6.

Kayongo and Van Jacob (2011) added 26 sub-categories to

the READ Scale, e.g. within level 3, there are categories such as “L3 Complex

known item search [Do we own?],” “L3 Online resource problem,” and “L3 Simple

citation verification”. Stieve and Wallace (2018) added the word “circulation”

as a bullet point in the definition of level 2 and expanded several of the

examples that accompany the definitions.

Local Interpretations

Specific READ Scale ratings were not always interpreted

to mean the same level of expertise. Belanger et al. (2016) defined points 3

and above as “requiring a complex response” (p. 12). Bungaro

et al. (2017) only reported the split between the highest 3 categories (i.e.,

4, 5, and 6), for which a subject specialist was justified and the lowest 3,

for which a 'generic' librarian was sufficient. Kemp et al. (2015), comparing

complexity of questions across modes, considered questions “complex” at ratings

3 and above and “basic” at 2 and below. They made a further distinction that a

score of 4 or above required librarian or subject librarian expertise. Using a

0-5 scale, Keyes and Dworak (2017) noted that 0-2

were considered to be “clearly” able to be addressed by graduate students. In

presenting the data, they also grouped 4 and 5, but without explanation.

Maloney and Kemp (2015) grouped 4 and above as requiring advanced expertise.

While Mavodza (2019) reported

counts for each point on the scale, she presented the groupings of the counts

at 2 and lower, writing “[w]hen analyzing the same chats from the READ Level,

most of them were at the one and two difficulty levels at 939 and 230,

respectively” (p. 128). Even though

level 3 had only 40 occurrences fewer than level 2, she grouped the level 3

count (n=190) with level 4 (n=98). She grouped the level 5 (n=26) and 6 (n=15)

together. These groupings suggest both affinities of content within the groups

as well as an intellectual divide between the groups.

Data Points Used in Conjunction with READ Scale

Many times, the READ Scale ratings were used in

conjunction with other data points, time measures being most common. Belanger

et al. (2016), Gerlich and Berard

(2010), and Maloney and Kemp (2015) each analyzed the READ Scale ratings by

point in the academic semester or quarter in order to understand the

relationship between the academic calendar and the complexity of reference

transactions. Cabaniss (2015), Kayongo and Van Jacob (2011), and Ward and

Jacoby (2018) compared ratings across times of day in order to understand

busyness patterns by hour. Cabaniss (2015) also looked at days of the week in

order to find the busiest and least busy days.

The second most-frequent variable used with the READ

Scale was the topic of the interaction. Bungaro et

al. (2017) were interested in the frequency of psychology-related chats and

whether they were, on average, more complex than others. Cabaniss

(2015) and Mavodza (2019), following the same

research protocol, assigned four categories to chats: general information,

technical, known item lookup, and reference. Kohler’s (2017) algorithm weighed

certain words more than others in order to algorithmically assign a READ Scale

rating. Ward and Jacoby (2018), studying referrals given in chat, compared the

READ Scale to their own categories of referral needed, referral provided,

appropriate referral, and referral gap. They found that referrals happened more

often as the complexity of the question increased, and also found that the

referral gap, or rate at which a referral was warranted but not given, also went

up with the complexity of the interaction as designated by the READ Scale.

Other metrics used in conjunction with the READ Scale to

determine service patterns included staffing types (Keyes & Dworak, 2017), delivery mode (Asher, 2014; Gerlich & Berard, 2010;

Maloney & Kemp, 2015; Ward & Jacoby, 2018), length of interaction, and

referral type (Ward & Jacoby 2018).

Goals of READ Scale Assessment

In some cases, such as in Larson et al. (2014), the READ

Scale chat data were reported as part of an overall assessment of reference

services, for which there was no particular insight or assessment-related

decision that the authors were using the READ Scale to understand. In one case,

the READ Scale ratings were used as a cut off for including transactions in a

different assessment effort (Valentine & Moss, 2017). Gerlich

and Berard (2010) and Belanger et al. (2016) were

interested in assessing the READ Scale itself, the latter concluding that the

READ Scale did not provide a sufficiently nuanced understanding of the

complexities of chat service provision.

Several uses for the READ Scale were found in multiple

articles, and these are summarized below.

Staffing Needs

Eleven articles used the READ Scale to determine

appropriate staff allocation, with the most common approach being to match READ

Scale ratings with the level of expertise required of the reference staff.

Often the six-point scale was reduced, in the data analysis, to two broad

categories: ratings that indicate a need for professional expertise, and those

that do not. This sort of grouping is implied by the logo for the READ Scale,

which depicts lines separating 5 and 6 from the lower numbers on the scale.

This division is not explicit in the scale’s definition, however, and as

discussed above, institutions located this split at varying points on the

scale.

Researchers found evidence to support a variety of

staffing recommendations, both in terms of number of staff assigned to

providing the service and the level of experience of staff providing the chat

service. Kemp et al. (2015) and Maloney and Kemp (2015), studying the

implementation of a proactive chat system at the University of Texas-San Antonio

library, found an increase in complex questions through the proactive system.

Because they defined READ Scale 4 and above as needing librarian-level

attention, an increase in librarians was needed to field the more frequent,

complex questions, and they subsequently used a multi-pronged approach to get

more librarians into the chat staffing mix (Kemp et al., 2015). Similarly, Bungaro et al. (2017) found evidence to maintain and keep

subject librarians answering a subject-specific chat channel, whereas they

assumed generalist librarians could adequately answer READ Scale 1-3. Further

evidence was found to keep professional librarians answering chat, arguing that

outsourcing late night chat service to consortial

librarians resulted in decreased quality of service (Kayongo & Van Jacob,

2011).

While some researchers found evidence for staffing

increases, Ward and Jacoby (2012) found that a rearrangement of staff to match

hour-by-hour patterns in chat may optimize which staff are most likely to

receive the most complex questions. However, the researchers ultimately

recommended a reduction in the experience level of chat staff, shifting to

graduate students exclusively. In another study, Keyes and Dworak

(2017) found evidence to recommend a reduction in professional

level/experience. Keyes and Dworak noted that

undergraduate students could adequately field chat at the READ Scale 1-3 level.

While many supported point-of-need staffing with

experienced or professional librarians, some suggest the tiered model was

adequate to address complex questions that could not be answered at the time

they were asked. In their study examining the rates of referrals and whether

they occurred as needed, Ward and Phetteplace (2012)

found that while the rates of referral went up with the READ Scale designation,

so did the rate of interactions that should have included a referral but did

not. The referral ecosystem was further complicated with the READ Scale when

staff members sometimes referred questions they rated as complex, but gave

little effort to answer on the spot (Belanger et al., 2016).

Comparison of Reference Configurations

Researchers in five articles used the READ Ratings to

compare different types of reference service. Four of the five compared passive

and proactive chat configurations (DeMars et al., 2018;

Kemp, et al., 2015; Maloney & Kemp, 2015; Warner et al., 2020). Each of

these researchers found that proactive chat systems resulted in more complex

transactions than passive chat configurations. Stieve and Wallace (2018)

compared sources of chat transactions, finding that READ Scale ratings were

higher from within the university’s learning management system as compared to

chats originating from the library website.

Gerlich and Berard (2010) compared all

modes of reference at the participating institutions: walk-up directional,

walk-up reference, phone directional, phone reference, email, and chat. The

difference between “directional” and “reference” phone and walk-up modes was

not explained. Chat transactions made up only about 1% of the transactions in

the study. A greater emphasis was on distinguishing between “walk up” in-person

desk interactions and those in-person interactions that happened in hallways

and offices: “The off-desk comparisons show… that the percentage of questions

answered off-desk for most of the institutions require a much higher level of

effort, knowledge, and skills from reference personnel than at the public

service point” (Gerlich & Berard,

2010, p. 125)

Other

Several researchers noted the higher degree of difficulty

in fielding chat rather than face-to-face interactions, difficulties that were

not represented in the READ Scale. Chat agents may have to field multiple chats

at the same time (Cabaniss, 2015; DeMars,

2018; Keyes & Dworak, 2017), and the necessity of

typing succinct directions without the ability to rely on non-verbal cues was

challenging (Gerlich & Berard,

2010). Librarians at one institution reported that multiple factors coalesced

into chat interactions being deemed as more stressful (Ward & Phetteplace, 2012).

The Ratings

While the READ Scale is a 6-point scale, the 1-4 range of

the scale was heavily used, while the 5-6 range was not. Belanger et al.

(2016), Gerlich and Berard,

(2010), Kohler (2017), Stieve and Wallace (2018), and Ward and Jacoby (2018)

found that zero chats were rated a 5 or 6. Kayongo and Van Jacob (2011), Cabaniss (2015), and Mavodza

(2019) found that the majority of chat interactions fell within the 1-3 range.

The one outlier was Bungaro et al. (2017), who found

that almost half (46%) of their chat interactions happened at the 4 or above

designation, though it is unclear how many were rated at each level.

Not every source provided a breakdown by each number,

with some providing percentages of ranges of READ Scale designations. However,

of those that did, the data showed the vast majority of transactions occurring

in the 1-4 range. Within the READ Scale 1-4 range, most chats are rated a READ

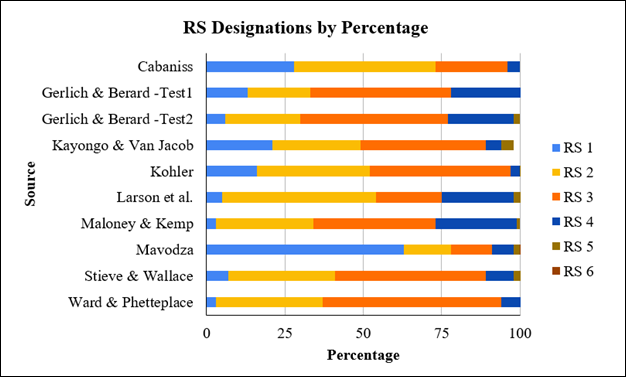

Scale 2 or 3 (see Figure 1).

Table 2

Summary of Articles, Including READ Scale Breakdowns

|

Author, Publication Date,

(Institution examineda) |

Chat sample size |

Breakdown by READ Scale

designation as reported by sourceb |

Timeframe of chats assessed

with READ Scale |

Sampling Method |

|

Asher, 2014 (University of Indiana, Bloomington) |

149 |

unstated |

2006-2013 |

Convenience |

|

Belanger et al., 2016 (University of Washington) |

3721 chat transcripts |

1=10% 2&3= 80% 4=10% 5=0 6=n/a |

Fall quarter 2014 (September-December) |

Convenience |

|

Bungaro et al., 2017 (University of Turin; Italy) |

121 |

1-3= 53.8% (n=65) 4-6= 46% (n=56) |

2014-2016 |

Convenience |

|

Cabaniss, 2015 (University of Washington) |

608 |

1=28% (n=169) 2=45% (n=275) 3=23%(n=142) 4=4%(n=27) 5=0% (n=2) 6=unstated |

3 sample weeks in winter term 2014 (January-March) |

Convenience |

|

DeMars et al., 2018 (California State University, Long Beach) |

unstated |

1=7-14% 2=32-32% 3=38-40% 4=7-15% 5=1-3% 6=.5-1% Gleaned from table |

2016-2018. Compared three chat configurations. |

Cluster |

|

Gerlich and Berard, 2010 (Multiple) |

Test 1: 98 Test 2: 317 |

Test 1: 1=13% (n=13) 2=19% (n=19) 3= 45% (n=44) 4=22% (n=22) 5=0% (n=0) 6=0% (n=0) Test 2: 1=6% (n=19) 2=24% (n=76) 3=47% (n=150) 4=21% (n=66) 5=2% (n=6) 6=0% (n=0) |

Test 1: 3 weeks in February, 2007 Test 2: Spring semester, 2007 |

Test 1: Convenience, Test 2: Adaptive |

|

Kayongo and Van Jacob, 2011 (University of Notre Dame) |

2517 |

1=21.1% (n=531) 2=28.3% (n=712) 3=40.4% (n=1017) 4=5.9% (n=1480 5=4.2% (n=105) 6=.1% (n=4) |

November 2007-May 2010 |

Convenience |

|

Kemp et al., 2015 (University of Texas, San Antonio) |

Test 1: unspecified Test 2: 287 Test 3: 228 |

Test 1: 3= 44% 4 and above= 21% Test 2: (triggered) 1,2 =19% 3 and above= 81% Test 3: (non-triggered) 1,2=37% 3 and above= 63% |

Test 1: Six sample weeks from Fall 2013 to Spring 2014. Tests 2 and 3: November 2013 |

Test 1: Convenience Tests 2 and 3: Cluster |

|

Keyes and Dworak, 2017 (Boise State University) |

454 |

0-1= 19% (n=78) 2= 31% (n=131) 3= 39% (n=164) 4-5= 11% (n=48) |

May 2014-Sept 2016 |

Convenience |

|

Kohler, 2017 (Rockhurst University) |

1109 |

0=7% (n=80) 1=15% (n=166) 2=33% (n=366) 3=41% (n=456) 4=3% (n=35) 5=1% (n=6) 6=0% (n=0) |

FY2015- FY2016 |

Convenience |

|

Larson et al., 2014 (University of Maryland) |

39 |

1=5% (n=2) 2=49% (n=19) 3=21% (n=8) 4=23% (n=9) 5=3% (n=1) 6=0% (n=0) |

2013 |

Convenience |

|

Maloney and Kemp, 2015 (University of Texas, San Antonio) |

2492 |

1=3% (n=85) 2=31% (n=764) 3=39% (n=968) 4=26% (n=654) 5=1% (n=19) 6=0% (n=2) |

6 sample weeks: Fall 2013 and Spring 2014 |

Cluster |

|

Mavodza, 2019 (Zayed University; United Arab Emirates) |

1498 |

1=63% (n=939) 2=15% (n=230) 3=13% (n=190) 4=7% (n=98) 5=2% (n=26) 6=1% (n=15) |

Feb 2013-Feb 2018 |

Convenience |

|

Stieve and Wallace, 2018 (University of Arizona) |

382 |

1=0% (n=2) 2=34% (n=128) 3=48% (n=184) 4=9% (n=33) 5=3% (n=13) 6=0% (n=0) |

Fall and Spring semesters for 2014 and 2015. |

Cluster |

|

Valentine and Moss, 2017 (University of Kansas) |

30 |

3 and above=100% (n=30) |

Fall semester 2016 |

Cluster |

|

Ward and Jacoby, 2018 (University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign) |

1120 |

1=30 (3%) 2=378 (34%) 3=636 (57%) 4=76 (7%) 5 and 6=unstated |

April 2015 |

Convenience |

|

Ward and Phetteplace, 2012 (University of Illinois. Urbana-Champaign) |

unspecified |

Unspecified |

Sept and Oct 2010 |

Convenience |

|

Warner et al., 2020 (University of New Mexico) |

4617 |

unspecified |

July 2016 to July 2018 |

Cluster |

a Country of institution is United States of America unless

otherwise indicated.

b When the source gives numbers only, review authors have converted these to

percentages and rounded to the whole number, but we have not used

percentage-only data to derive hard numbers. Because of this, percentages are

recorded in the 100-101 range.

Figure 1

READ Scale ratings for chat interactions from articles

that provided breakdowns by each READ Scale number. Gerlich

and Berard (2010) reported two tests in “Testing the Viability

of the READ Scale.”

Discussion

Perhaps unsurprisingly, a primary goal in using the READ

Scale at many institutions was to understand staffing needs. Many analyzed READ

Scale designations by time of day, day of week, and time in the academic period

in order to find patterns of busiest times and most complex questions,

following assessment trends Luo identified in 2008. Understanding demand for

service is an admirable goal, but unfortunately even when service patterns are

present, staffing models may not provide the flexibility to checkerboard staff

shifts to match them. And, while optimizing staffing may be possible to a

degree, in practice, complex questions can arrive at any point in the day,

week, or year and service coordinators must determine what is adequate, rather

than optimal, service. Additionally, READ scores were used to make inferences

about the level of expertise needed, most often a recommendation for decreased

expertise, and none of the sources articulated how they would determine when

they had sub-adequate staffing levels on chat. This use of the READ Scale,

while seemingly common, is troubling.

The most striking feature of the READ Scale data was the

paucity of chat transactions rated 5 or 6. Indeed, this was reflected in Gerlich and Berard’s (2010)

viability study data. None of the 15 testing institutions reported any chat

transactions falling into the 5 or 6 ratings. However, it would be premature to

conclude that patrons are not asking complex questions, based solely on ratings

of the responses to those questions. As Gerlich and Berard developed the READ Scale, they theorized that more

complex questions were answered away from the reference desk, such as in

hallways or offices, and they built this assumption into the scale. For

example, the definitions provided for the 5 and 6 ratings assume or presuppose

the interaction occurring outside of initial reference contexts. Level 5

suggests that “consultation appointments might be scheduled” (Gerlich, n.d.) while level 6 specifies that “(r)equests for information cannot be answered on the spot” (Gerlich, n.d.). In practice, this makes the higher end of

the scale unavailable to chat transactions. As of this writing, it is not

feasible for a librarian to initiate a chat with a specific patron or schedule

a consultation via chat, so any question that requires follow up is necessarily

answered in a different mode. The scale gives weight to the mode in which the

librarian answers reference questions, rather than the mode in which the patron

asks it.

Depending on how the READ Scale ratings are used by an

institution, the data could present a distorted view of the chat service. For

example, if a question comes in via chat that is beyond the abilities of that

librarian, they might create a ticket that the relevant subject specialist will

claim. While the eventual answer would likely be a 5 or 6, the chat transaction

would rate as a 1, as it took no effort. If the staff member used knowledge or

training about who specifically to refer the question to, or instructed the

patron in how to schedule a consultation, it might appropriately rate at level

2 or 3. In any case, it would be at the low end of the scale, indistinguishable

from simple item searches or questions about hours. Using READ Scale data to

determine the level of expertise required of chat staff is problematic when

questions that staff could answer comfortably and those they lacked the

expertise to answer at all are represented the same way in the data.

It is also notable that almost every study in this review

tabulated READ Scale designations based simply on frequency, either as raw

counts or percentages. This gives equal weight to all questions; imagine a one

hour reference shift in which a librarian has two questions at level 4,

spending 15 minutes on each working with the patrons to choose a database,

develop and refine search strategies, and so on. That librarian also spends ten

seconds on each answer to questions about the hours. If there are five such

questions, the hour was predominantly level 1, even though less than a minute

was spent on level 1 answers, and half the hour was spent on level 4 responses.

This approach essentially recreates the hash mark system that the READ Scale

was developed to replace, with the added misinterpretation that most questions

can be answered without any specialized knowledge or skill.

This unequal weight distribution is true for all modes of

reference, but is especially significant for chat, where librarians report

fielding multiple questions at a time. Answering several questions about hours

or renewals while a patron requiring more complex assistance is running

searches is efficient. An approach to assessment that devalues this practice is

flawed.

Measuring the skills needed to answer a question makes

sense when trying to assess how to staff the service. It can be less helpful

when trying to assess the value of the service to our patrons. Helping a patron

navigate a confusing record or misconfigured link in a database may be a simple

question from the librarian’s perspective, perhaps rating a 2 on the READ

Scale. From the patron’s perspective, getting access to the resource may be

critically important. A low READ score might be desirable in this case: the

librarian was able to solve the patron’s problem quickly and easily. Yet, the

interpretation of the READ Scale may rank the worthiness of some questions or

answers over others, a common trap inherent in scales (LeMire

et al., 2016).

Given the language limiting chat to the lower end of the

READ Scale, we might see a rash of adaptations of the definitions and examples,

creating the ability of chat to enter into the final third of the READ Scale.

However, of the few institutions that adapted the READ Scale verbiage to their

local assessment environments, mode-agnostic wording was not added at the upper

levels, and mode-specific language was not deleted. Because the majority of

institutions did not alter the language of the Scale at all, it may be that

critical analysis of the viability of the tool explicitly for chat was absent

or that librarians agreed with the existing wording of the scale. If librarians

adhere to the existing wording of the scale, they implicitly agree that

regardless of time invested or librarian resources used, chat content will

never equate to the same content delivered face-to-face in a traditional

consultation. If librarians assess chat in direct comparison to face-to-face,

or indeed other modes of delivery, the assessment reflects bias by creating an

implicit hierarchy of service.

While the READ Scale language may constrict chat

transactions to the lower two-thirds of the scale, experience with complex

content may have a similar effect. Less experienced chat agents do not have as

deep a skillset with which to call upon in chat interactions, leaving their

choice of READ Scale rating constricted. So, if an institution staffs chat with

less experienced undergraduate students, the READ Scale ratings should reflect

that restricted ability, resulting in lower-rated chats. In contrast, highly experienced

librarians have the ability to answer inquiries farther up the READ Scale.

Further, the judgement of complexity is compounded by more experienced

librarians’ increased familiarity and expertise: librarians who walk students

through the intricacies of searching databases may be more familiar with the

content and thus rank those interactions as less complex.

Limitations

The findings of this literature review are limited in

several ways. Because we were attempting to understand the variety of

situations in which the READ Scale has been deployed to measure chat, we did

not limit the scope of material to academic journal articles. The resultant

formats provide variable depth of information. For example, only half of the articles included provided the breakdown

of READ Scale ratings by each of its six levels, while the others reported only

clusters of ratings. Some provided in-depth explanations of READ Scale ratings

results and extensive analysis, and others did not. For some of the articles,

chat reference was a brief focus of a comprehensive reference service

evaluation. More broadly, many institutions used the READ Scale to assess

reference interactions, as evidenced by our initial searches, however it is

unclear exactly how many institutions used the READ Scale to assess chat.

Evidence from community colleges and additional international sources could

inform future research and help to address this knowledge gap. Finally, we

recognize that not all chat service coordinators publish their assessment

efforts, so direct research with this population may provide insight into READ

Scale reach, variations in application, and changes in the quantity and

experience levels of chat agents after using it for assessment.

Conclusion

Pomerantz et al. (2008) argued that when assessing chat

reference, “’Good enough’ data is better than no data when one is aware of the

limitations of the data” (p. 27). The READ Scale has been adopted across the

globe to assess online synchronous interactions, yet this tool was developed

before chat reference became commonplace (Matteson et al., 2011). In this

literature review, we set out to understand how librarians use the tool to make

decisions and understand resultant data when examining chat reference service.

This was a first step to understanding whether the READ Scale has withstood the

test of time as chat has evolved to play a much bigger role in reference

service.

Based on the data that have been published and reviewed

herein, the READ Scale systematically undervalues chat reference transactions

for many of the assessment goals for which it is used. Ultimately, the way the

READ Scale is applied and interpreted with regards to chat reference is at odds

with the intent of the tool. Rather than capturing the knowledge, skills, and

abilities needed to provide adequate reference service, it overemphasizes the

simplest, least time consuming questions, with the effect of making chat

reference appear not worth the cost of staffing with experienced professionals.

We are not providing recommendations here about the

correct level of staffing for chat reference. Our concern is that the

assessment that libraries do to make those decisions are appropriate and

accurate. We therefore propose a number of recommendations for practice.

Recommendations for Practice

Based on our understanding of how the READ Scale has been

used by librarians to conflate complexity, experience, and value, we invite

practitioners to reflect on the following recommendations:

1.

Use caution when

comparing face-to-face, chat, email, text, and phone interactions to each other

using the existing definitions and examples provided in the READ Scale

documentation.

2.

Examine and update

the definitions and examples of each level of the READ Scale through the lens

of each reference delivery method your library provides.

3.

If you are trying

to understand the expertise needed to staff the service, consider rating every

question that staff could not answer as a 6. These are questions that cannot be

answered “on the spot” with your current staffing model.

4.

If you are trying

to understand the service overall, consider reporting the time spent on each

level of answer, rather than the number or percent of questions at each level.

Alternately, you could develop a system of weights for each READ Scale number

in order to represent expertise needed for the length of the interaction.

Author Contribution Statement

Adrienne Warner:

Conceptualization,

Data Curation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Supervision,

Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing David A. Hurley: Conceptualization,

Data Curation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Writing – original draft,

Writing – review and editing

References

Asher, A. (2014). Who’s asking

what? Modelling a large reference interaction dataset. Proceedings of

the 2014 Library Assessment Conference, 52-62. https://www.libraryassessment.org/past-conferences/2014-library-assessment-conference

Belanger, J., Collins, K., Deutschler, A., Greer,

R., Huling, N., Maxwell, C., Papadopoulou,

E., Ray, L. & Roemer, R. C. (2016). University

of Washington Libraries chat reference transcript assessment. https://www.lib.washington.edu/assessment/projects/chat-reference-assessment-project-2014-2016-final-report

Bungaro, F., Muzzupapa, M. V., & Tomatis,

M. S. (2017). Extending the live chat reference service at the University of

Turin - A case study. IATUL Annual

Conference Proceedings, 1–12. https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/iatul/2017/challenges/1/

Cabaniss, J. (2015). An assessment of the University of Washington’s chat

reference services. Public Library

Quarterly, 34(1), 85–96. https://doi.org/10.1080/01616846.2015.1000785

DeMars, M. M., Martinez,

G., Aubele, J., & Gardner, G. (2018, December 7).

In your face: Our experience with

proactive chat reference

[Conference presentation]. CARLDIG-S Fall 2018 Program, Los Angeles, CA,

United States. http://eprints.rclis.org/33775/

Gerlich, B. K. (n.d.). READ Scale bulleted format.

The READ Scale©: Reference Effort Assessment Data. http://readscale.org/read-scale.html

Gerlich, B. K., & Berard, G. L. (2007). Introducing the READ Scale:

Qualitative statistics for academic reference services. Georgia Library Quarterly, 43(4),

7-13. https://digitalcommons.kennesaw.edu/glq/vol43/iss4/4

Gerlich, B. K., & Berard, G. L. (2010). Testing the viability of the READ

Scale (Reference Effort Assessment Data)©: Qualitative

statistics for academic reference services. College

& Research Libraries, 71(2),

116-137. https://doi.org/10.5860/0710116

Gerlich, B. K., &

Whatley, E. (2009). Using the READ Scale for staffing strategies: The Georgia

College and State University experience. Library

Leadership & Management, 23(1),

26-30. https://journals.tdl.org/llm/index.php/llm/article/download/1755/1035

Heyvaert, M.,

Hannes, K., & Onghena, P. (2016). Using mixed methods research synthesis for

literature reviews: The mixed methods research synthesis approach (Vol. 4).

Sage Publications.

Hirko, B. (2006). Wally:

Librarians' index to the internet for the state of Washington. Internet

Reference Services Quarterly, 11(1), 67-85. https://doi.org/10.1300/J136v11n01_06

Kayongo, J., & Van Jacob, E. (2011). Burning the midnight oil:

Librarians, students, and late-night chat reference at the University of Notre

Dame. Internet Reference Services Quarterly,

16(3), 99–109. https://doi.org/10.1080/10875301.2011.597632

Kemp, J. H., Ellis, C. L., & Maloney, K. (2015). Standing by to help:

Transforming online reference with a proactive chat system. The Journal of Academic Librarianship, 41(6), 764–770. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2015.08.018

Keyes, K., & Dworak, E. (2017). Staffing chat

reference with undergraduate student assistants at an academic library: A

standards-based assessment. The Journal

of Academic Librarianship, 43(6),

469–478. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2017.09.001

Kohler, E. (2017, November 3). What do your library chats say?: How to analyze webchat transcripts for sentiment and

topic extraction. Brick & Click

Libraries Conference Proceedings, 138–148. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED578189.pdf

Larson, E., Markowitz, J., Soergel, E., Tchangalova, N., & Thomson, H. (2014). Virtual information services task force

report. University of Maryland University Libraries. https://doi.org/10.13016/M2GT5FH7N

LeMire, S., Rutledge, L.,

& Brunvand, A. (2016). Taking a fresh look: Reviewing and classifying

reference statistics for data-driven decision making. Reference & User Services Quarterly, 55(3), 230-238.

Luo, L. (2008). Chat reference evaluation: A framework of perspectives and

measures. Reference Services Review, 36(1), 71–85. https://doi.org/10.1108/00907320810852041

Maloney, K., & Kemp, J. H. (2015). Changes in reference question

complexity following the implementation of a proactive chat system:

Implications for practice. College &

Research Libraries, 76(7),

959–974. https://doi.org/10.5860/crl.76.7.959

Matteson, M. L., Salamon, J., & Brewster, L.

(2011). A systematic review of research on live chat service. Reference

& User Services Quarterly, 51(2), 172-190. https://doi.org/10.5860/rusq.51n2.172

McLaughlin, J. E. (2011). Reference transaction assessment: Survey of a

multiple perspectives approach, 2001 to 2010. Reference Services Review,

39(4), 536-550. https://doi.org/10.1108/00907321111186631

Mavodza, J. (2019).

Interpreting library chat reference service transactions. Reference Librarian, 60(2),

122–133. https://doi.org/10.1080/02763877.2019.1572571

Mungin, M. (2017). Stats

don't tell the whole story: Using qualitative data analysis of chat reference

transcripts to assess and improve services. Journal of Library &

Information Services in Distance Learning, 11(1-2), 25-36. https://doi.org/10.1080/1533290X.2016.1223965

Nicol, E. C., & Crook, L. (2013). Now it's necessary: Virtual reference

services at Washington State University, Pullman. The Journal of Academic

Librarianship, 39(2), 161-168. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2012.09.017

Novotny, E. (2002, September). Reference service statistics &

assessment. Association of Research Libraries. https://www.arl.org/resources/spec-kit-268-reference-service-statistics-a-assessment-september-2002/

Pomerantz, J., Mon, L. M., & McClure, C. R. (2008). Evaluating remote

reference service: A practical guide to problems and solutions. portal:

Libraries and the Academy, 8(1), 15-30. https://doi.org/10.1353/pla.2008.0001

Rabinowitz, C. (2021). You keep using that word: Slaying the dragon of

reference desk statistics. College & Research Libraries News, 82(5),

223-224. https://doi.org/10.5860/crln.82.5.223

Reference and User Services Association. (2017). Guidelines for

implementing and maintaining virtual reference services. http://www.ala.org/rusa/sites/ala.org.rusa/files/content/resources/guidelines/GuidelinesVirtualReference_2017.pdf

Ronan, J., Reakes, P., & Cornwell, G. (2003).

Evaluating online real-time reference in an academic library: Obstacles and

recommendations. The Reference Librarian, 38(79-80), 225-240. https://doi.org/10.1300/J120v38n79_15

Sarah. (2012, March 21). LibAnswers-

new features are live! Springshare.

https://blog.springshare.com/2012/03/21/libanswers-new-features-are-live/

Schwartz, H. R., & Trott, B. (2014). The application of RUSA standards

to the virtual reference interview. Reference and User Services Quarterly,

54(1), 8-11. https://journals.ala.org/index.php/rusq/article/view/3993/4505

Stieve, T., & Wallace, N. (2018). Chatting while you work. Reference Services Review, 46(4), 587–599. https://doi.org/10.1108/RSR-09-2017-0033

Valentine, G., & Moss, B. D. (2017, March 28). Assessing reference service quality: A chat transcript analysis [Conference presentation]. Association

of College and Research Libraries Conference, Baltimore, MD. http://hdl.handle.net/1808/25179

Ward, D., & Jacoby, J. (2018). A rubric and methodology for

benchmarking referral goals. Reference

Services Review, 46(1), 110-127. https://doi.org/10.1108/RSR-04-2017-0011

Ward, D., & Phetteplace, E. (2012). Staffing

by design: A methodology for staffing reference. Public Services Quarterly, 8(3),

193–207. https://doi.org/10.1080/15228959.2011.621856

Warner, A., Hurley, D. A., Wheeler, J., & Quinn, T. (2020). Proactive

chat in research databases: Inviting new and different questions. The Journal of Academic Librarianship, 46(2), 102-134. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2020.102134

White, M. D. (2001). Digital reference services: Framework for analysis and

evaluation. Library & Information Science Research, 23(3),

211-231. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0740-8188(01)00080-9